Abstract

The community structure of pink-colored microbial mats naturally occurring in a swine wastewater ditch was studied by culture-independent biomarker and molecular methods as well as by conventional cultivation methods. The wastewater in the ditch contained acetate and propionate as the major carbon nutrients. Thin-section electron microscopy revealed that the microbial mats were dominated by rod-shaped cells containing intracytoplasmic membranes of the lamellar type. Smaller numbers of oval cells with vesicular internal membranes were also found. Spectroscopic analyses of the cell extract from the biomats showed the presence of bacteriochlorophyll a and carotenoids of the spirilloxanthin series. Ubiquinone-10 was detected as the major quinone. A clone library of the photosynthetic gene, pufM, constructed from the bulk DNA of the biomats showed that all of the clones were derived from members of the genera Rhodobacter and Rhodopseudomonas. The dominant phototrophic bacteria from the microbial mats were isolated by cultivation methods and identified as being of the genera Rhodobacter and Rhodopseudomonas by studying 16S rRNA and pufM gene sequence information. Experiments of oxygen uptake with lower fatty acids revealed that the freshly collected microbial mats and the Rhodopseudomonas isolates had a wider spectrum of carbon utilization and a higher affinity for acetate than did the Rhodobacter isolates. These results demonstrate that the microbial mats were dominated by the purple nonsulfur bacteria of the genera Rhodobacter and Rhodopseudomonas, and the bioavailability of lower fatty acids in wastewater is a key factor allowing the formation of visible microbial mats with these phototrophs.

Among anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria, the purple sulfur bacteria and the green filamentous bacteria occasionally appear in visible concentrations in natural and manmade environments. Since the pioneer work by Miyoshi in 1897 (37), geothermal hot springs have received much attention as the habitats allowing these bacteria to form colored microbial mats and blooms (for reviews, see references 7, 16, and 33). The massive growth by the phototrophic sulfur bacteria have also been found in tidal seawater pools (45), hypersaline environments (27, 30, 38, 44, 47), and stabilization lagoons (9, 42, 50). On the other hand, phototrophic purple nonsulfur (PPNS) bacteria have been considered to rarely appear in massive development in nature, although the metabolic diversity of these bacteria allows them to occupy a broad range of environments (28, 33). Low dissolved oxygen (DO) tension and the high availability of light and simple organic nutrients, as is the case in nutrient-rich stagnant water bodies, are important factors promoting the proliferation of PPNS bacteria in the environment. However, the physicochemical threshold of massive growth by PPNS bacteria under natural conditions remains unidentified.

Our previous studies have shown that PPNS bacteria occasionally occurred in high numbers in wastewater treatment plants operating under highly aerated and light-limited conditions (23, 25, 39). The results of these studies have suggested that the availability and kind of lower fatty acids in wastewater are additional important factors affecting the population density and phylogenetic composition of PPNS bacteria. Also, there have been studies of photosynthetic blooms resulting from the temporal development of PPNS bacteria in anaerobic swine waste lagoons (11) and tidal seawater pools (26). The study of lagoon blooms suggests that the organic loading and temperature of water are the main parameters controlling the blooms. To date, however, there have been no reports on colored microbial mats or biofilms with PPNS bacteria as the major constituents of phototrophs.

In the present study, we report colored microbial mats developing in a swine wastewater ditch, as another event caused by dense populations of PPNS bacteria. The diversity and phylogenetic composition of PPNS bacteria within the colored mats were studied by microscopy, biomarker profiling, and PCR cloning and sequencing of the pufM gene, coding for the M subunit of the photosynthetic reaction center protein. The clone library analysis of the pufM gene has been reported as a promising approach to the phylogenetic characterization of phototrophic bacterial communities in aquatic and hot spring environments (1, 6, 51). In addition to the culture-independent approaches noted above, the dominant PPNS bacteria from the colored biomats were isolated by conventional cultivation methods and compared with the biomats in oxygen uptake with different lower fatter acids. Ecophysiological factors allowing the formation of PPNS bacterial mats in the environment are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mat and wastewater samples.

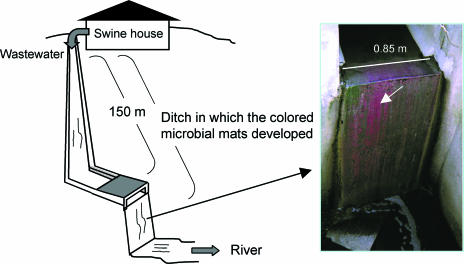

The swine wastewater ditch investigated is a part of the drainage arrangements of a pig farm located in Kosai, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan. The ditch measures approximately 0.33 to 0.85 m in width and 150 m in length and has a straight and swift stream of wastewater daily flushed from the swine house containing 200 sows (Fig. 1). The wastewater was flowing continuously in the ditch. Most parts of the ditch are exposed to sunlight. Wastewater and microbial mats were collected from the surface of the ditch at about 2 to 3 h after sunrise between May 2003 and September 2005. These samples were stored in an insulated cooler if they were subjected to examination immediately upon return to the laboratory or were stored at −20°C if they were analyzed later.

FIG. 1.

Schematic outline of the swine wastewater ditch studied and a photograph showing the appearance of pink-colored microbial mats (indicated by an arrow).

Physicochemical analyses.

Temperature, pH, and ammonia were determined according to the standard methods (4). Total organic carbon was measured with a Shimadzu model 5000A TOC analyzer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Lower fatty acids in the wastewater were directly separated and identified by ion-pair high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with external standards as described previously (39). Inorganic anions were analyzed by using a Hitachi model D-7500 ion chromatograph equipped with a Hitachi L-2740 packed column (4.6 by 150 mm) and a Hitachi L-7470 conductivity detector. Samples were eluted at 37°C and at a flow rate of 1.5 ml min−1 with a mixture of 2.3 mM phthalic acid and 2.5 mM 2-amino-2-hydroxymethyl-1,3-propanediol as the mobile phase.

Pigment and quinone analyses.

Microbial mat samples were washed twice with 50 mM phosphate buffer and sonicated three times on ice for 3 min (20 kHz; output power, 100 W) to obtain cell extract. Absorption spectra of the cell extracts were measured with a Shimadzu BioSpec-1600 spectrophotometer. Bacteriochlorophyll (BChl) from mat samples was extracted with an acetone-methanol mixture (7:2, vol/vol) and measured spectrophotometrically. The concentration of BChl a was determined at 770 nm using a molar extinction coefficient of 75 mM cm−1 (8). Microbial quinones were extracted with an organic solvent mixture and fractionated into the menaquinone and ubiquinone fractions using Sep-Pak Vac silica gel cartridges (Waters, Milford, MA). Quinone components of each fraction were separated and identified by reverse-phase HPLC, photodiode array, and mass spectrometry detection with external standards. Detailed information on these analytical procedures has been given in previous studies (19, 29).

Phase-contrast and electron microscopy.

Phase-contrast microscopy was performed using an Olympus BX50 microscope equipped with an Olympus DP70 camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). For electron microscopy, microbial mats were fixed with glutaraldehyde and postfixed with osmium tetroxide. Ultrathin sections were prepared with an ultramicrotome, stained with lead acetate and uranyl acetate, and observed under a JOEL JEM-1200EX transmission electron microscope as described previously (35).

Construction of puf gene clone library.

Bulk DNA was extracted from mat samples according to the protocol of Hiraishi et al. (20). The crude DNA extracted was purified according to a standard protocol consisting of RNase digestion, chloroform-isoamyl alcohol treatment, and ethanol precipitation (34). The purified DNA was dissolved in TE buffer, diluted as needed, and used as the PCR template. For PCR amplification of the pufM gene, two primer sets were used; one primer set consisted of pufM.557F and pufM.750R (1) and the other was a combination of M150f (5′-AGATYGGYCCGATCTAYCT-3′) and M572r (5′-CCAGTCSAGGTGCGGGAA-3′). The PCR primers of the latter set were designed in this study on the basis of the pufM sequence data retrieved from the DNA databases. PCR was performed using an rTaq DNA polymerase kit (Takara, Otsu, Japan), one of the primer sets, and a Takara Thermal Cycler. The thermocycling profile consisted of preheating at 95°C for 2 min, 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 53°C for 1 min, extension at 72°C for 1 min, and postextension for 10 min. The PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, purified using a GENECLEAN Spin kit (Bio 101, Vista, CA), and subcloned using a pMosBlue blunt-ended vector kit (Amersham Bioscience, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). Ligation and transformation into Escherichia coli competent cells were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmid DNA was extracted and purified by using the Wizard Plus Minipreps DNA purification system (Promega Inc., Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis.

Cloned DNA samples were sequenced with a BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit and analyzed with a 3100-Avant genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Compiling of nucleotide sequence data and translation to amino acid sequences were performed with the GENETYX-MAC program (GENETYX Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Sequence data were compared with those deposited with the DNA data banks using the BLAST search system (3). Multiple alignment of sequences and calculation of the nucleotide substitution rate (Knuc) with Kimura's two-parameter model (31) were performed using the CLUSTAL W program (46). Distance matrix trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method (40), and the topology of the trees was evaluated by bootstrapping with 1,000 resamplings (13). Alignment positions with gaps were excluded from the calculations.

Isolation of PPNS bacteria.

Mat samples were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in the same volume of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and then sonicated on ice for 1 min (20 kHz; output power, 50 W). The dispersed samples were serially diluted with this buffer, and appropriate dilutions were plated by the pour-plating method with SAYS agar medium (pH 6.8), which contained acetate, succinate, and yeast extract as the carbon sources (39). Inoculated plates were incubated anaerobically with the AnaeroPak system (Mitsubishi Gas Chemical Co., Niigata, Japan) under incandescent light (ca. 2,000 lx). After 10 days of incubation, individual colored colonies were picked up at random and subjected to a standard purification procedure by streaking of agar plates. Purified isolates were preserved in MYS stub cultures (22).

Phylogenetic identification.

The isolates were identified phylogenetically by sequencing of 16S rRNA and pufM genes. For PCR amplification of these genes, a crude cell lysate from the isolates was prepared as the source of genomic DNA according to a protocol previously described (18). The 16S rRNA genes from the cell lysate were PCR amplified with bacterial universal primers fD1 (27f) and rP2 (1492r) (49) as described previously (18). Fragments of the pufM gene were also amplified with the PCR primers as described above. PCR products were purified by the polyethylene glycol precipitation method (21), sequenced, and phylogenetically analyzed as noted above.

Oxygen uptake measurement.

Four representative new isolates of the PPNS bacteria and the microbial mats were used for oxygen uptake measurement. For comparison, Rhodobacter azotoformans strain KA25T, Rhodobacter blasticus strain DSM 2131T, Rhodobacter veldkampii strain NBRC 16458T, and Rhodopseudomonas palustris strain ATCC 17001T were used. Cultures used for tests were grown semiaerobically or anaerobically under incandescent illumination as described previously (39). Cells at the mid-exponential phases of growth were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and resuspended in this buffer to give an optical density at 660 nm of 2.0 to 2.5. Cells from microbial mats were also harvested by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in phosphate buffer as noted above. These cell suspensions were immediately used for oxygen uptake measurement. Oxygen uptake was measured at 25°C using an Iijima model B-505 DO analyzer and with 2 mM (each) acetate, propionate, butyrate, valerate, and caproate as the substrate as described previously (39). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Kinetic analysis.

Kinetic analyses were conducted on the basis of data on oxygen uptake with acetate as the substrate. The concentration of acetate used ranged from 0.1 to 10 mM. The apparent maximum velocity (Vmax) and Michaelis-Menten constant were calculated from a Lineweaver-Burk plot. Following the lead of Folsom et al. (15), the term Ks was employed instead of Km because the activity was measured using intact cells rather than purified enzymes.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited under DDBJ accession numbers AB251404 to AB251412 for the 16S rRNA gene sequences and AB251413 to AB251455 for the pufM gene sequences.

RESULTS

Appearance and general characteristics of wastewater and colored mats.

The wastewater in the ditch was alkaline (pH 8.4 to 9.2) and had a temperature range of 19 to 22°C when sampling was performed. It contained lower fatty acids, with acetate and propionate as the major components and relatively high concentration of ammonia and sulfate (Table 1). Compared with the concentration of total organic carbon, it was evident that the lower fatty acids were the main organic components in the wastewater. The concentrations of these components varied greatly during the course of the study, but their maximum levels were sufficient to grow the phototrophic bacteria. The wastewater did not have sulfide odor, and no precipitation of elemental sulfur was visible around the rims of the ditch.

TABLE 1.

Chemical composition of the swine wastewater

| Component | Concn (mg liter−1)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean | Range | |

| Total organic carbon | 220 | 120-390 |

| Acetate | 350 | 150-740 |

| Propionate | 220 | 160-260 |

| NH4+-N | 230 | 74-530 |

| NO3− and NO2− | 2.6 | 0.61-3.9 |

| SO42− | 100 | 34-160 |

The fully pink-colored microbial mats were developing in the swine wastewater ditch for most of the year. The colored mats entirely covered the rough bottom of the ditch over 150 m not only in the areas exposed to sunlight but also in those shaded by trees and weeds (Fig. 1). The biomats never exceeded a few mm in thickness because the water column in the ditch was quite shallow, with the maximum depth of 1 cm and below. Although it was difficult to measure DO tension in the microbial mats because of their thin thickness, such a shallow, water-flowing habitat has greater contact with air and thus should contain high DO tension in the surface area. However, the fully pigmented growth and high amounts of BChl a in the microbial mats (see below) evidenced that the phototrophic bacteria present were allowed to perform photosynthesis, with a sharp oxic-anoxic gradient possibly taking place. The colored mats were always stabilized within a gelatinous matrix, suggesting that the microbial constituents were actually under anaerobic to semianaerobic conditions.

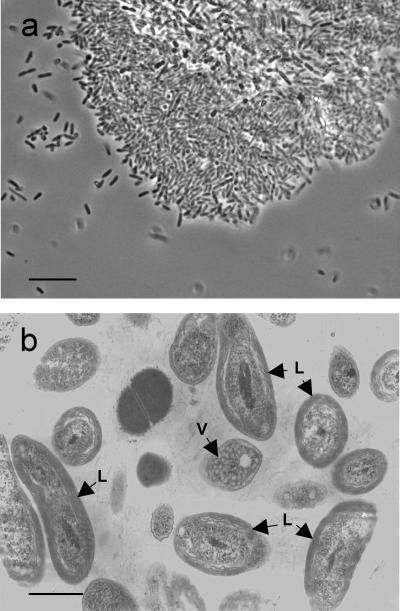

Microscopic observations.

Under a phase-contrast microscope, the microbial mats were observed as dense bacterial cell aggregates with rod-shaped cells predominating and oval cells as the second most frequent morphotype (Fig. 2a). The rod-type cells were distributed randomly in the mats, whereas the oval cells were found near the centers of the mats. Neither elemental sulfur-deposited cells nor extracellular sulfur granules were found. Thin-section electron microscopy of the biomats showed that the majority of the cells contained extensive intracytoplasmic membranes (Fig. 2b). Among these cells, 70% were budding rods with internal membranes of the lamellar type. The remainder had oval to coccoid cells and contained an internal membrane system of the vesicular type. The proportion of the two morphotypes occurring remained relatively constant regardless of sampling locations and season.

FIG. 2.

Microscopic observations of the colored microbial mats. (a) Phase-contrast micrograph of the colored microbial mats. Bar, 10 μm. (b) Transmission electron micrograph of ultra-thin sections of the colored microbial mats. Bar, 0.5 μm. Arrows with L and V indicate the development of lamellar and vesicular intracytoplasmic membranes within cells, respectively.

The aforementioned observations suggested that the DO concentration in the core of the microbial mats was low enough for the phototrophic bacteria to develop intracytoplasmic membranes and perform photosynthesis. Among species of PPNS bacteria, the lamellar and vesicular types of photosynthetic membranes are found mainly in those belonging to the orders Rhizobiales and Rhodobacterales within the class Alphaproteobacteria, respectively (28).

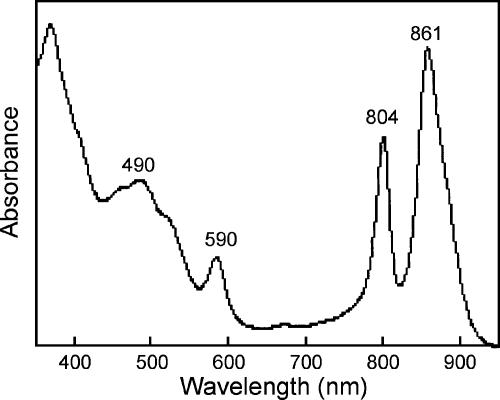

Pigments and quinones.

An absorption spectrum of the cell extract from the colored mats yielded major peaks at 490, 804, and 861 nm (Fig. 3), indicating the presence of BChl a incorporated into the photosynthetic reaction center and peripheral pigment-protein complexes and carotenoids of the spirilloxanthin series. The absorption spectra of acetone-methanol extract of the microbial mats showed an extinctive peak at 770 nm (data not shown), which is typical of BChl a. The amount of BChl a in the mat ranged from 4.4 to 4.6 μmol g−1 (dry weight).

FIG. 3.

Absorption spectrum of the cell extract from the colored microbial mats. Wavelengths (nm) of absorption maxima are shown at the tops of peaks.

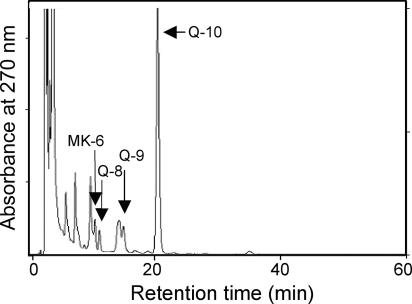

HPLC profiling of quinones from the microbial mats revealed that ubiquinone-10 (Q-10), a good lipid biomarker of the Alphaproteobacteria (19), was the major component, accounting for 87 mol% of the total quinone content on average (Fig. 4). Much smaller amounts of other ubiquinone species and menaquinones were also found. The quinone profiles of the microbial mats are much simpler than those previously recorded for sewage microbial mats (29).

FIG. 4.

HPLC elution profiles of quinones (ubiquinone plus menaquinone fractions) extracted from the colored microbial mats.

Pigment and quinone analyses as well as microscopic observations demonstrate that PPNS bacteria belonging to the Alphaproteobacteria predominated and performed photosynthesis in the microbial mats.

Isolation and identification of purple nonsulfur bacteria.

To confirm the predominance of the phototrophic alphaproteobacteria in the ditch microbial mats, these bacteria were quantitatively isolated by the pour-plating method. As a result, the microbial mats yielded high numbers of PPNS bacteria in the order of 108 CFU g−1 (wet weight). From these agar plates used for the enumeration, 9 strains of PPNS bacteria (designated strains TUT3629 to TUT3631 and TUT3731 to TUT3736) were isolated.

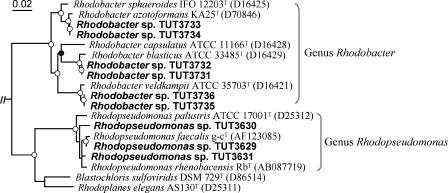

Nearly complete 16S rRNA gene sequences of the PPNS bacterial isolates (1,386 to 1,451 bp) were determined for their phylogenetic assignment. Of the 9 isolates, 6 were identified as members of the genus Rhodobacter, and the remainder were affiliated with the genus Rhodopseudomonas (Fig. 5). The closest relatives of the Rhodobacter isolates were Rhodobacter blasticus strain ATCC 33485T for strains TUT3731 and TUT3732 (99.2% similarity), Rhodobacter azotoformans strain KA25T for strains TUT3733 and TUT3734 (99.7%), and Rhodobacter veldkampii strain ATCC 35703T (99.7%) for strains TUT3735 and TUT3736. Three Rhodopseudomonas strains, TUT3629, TUT3630, and TUT3631, most resembled Rhodopseudomonas faecalis strain g-cT (98.1 to 99.2% similarity). Thus, although the 9 isolates were closely related to one of the previously known species of the genera Rhodobacter and Rhodopseudomonas, it was difficult to identify them at the species level only by studying 16S rRNA sequence information.

FIG. 5.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree for the isolates and related strains of PPNS bacteria based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences. The isolates are shown in boldface type. The tree is rooted with Chloroflexus aurantiacus strain DSM 637T (AJ308501) as an out-group. Bar, 2% nucleotide substitutions (Knuc). Accession numbers for the sequences are shown in parentheses following each strain designation. Nodes showing a bootstrap percentage of more than 85% and of 60 to 84% (1,000 resamplings) are indicated by the open and filled circles, respectively.

All of the new isolates contained Q-10 as the major quinone and grew optimally in slightly alkaline conditions (pH 7.0 to 8.0). Most Rhodobacter isolates were self-flocculated during phototrophic growth. No flocculated growth was found in any of the authentic strains of the Rhodobacter species.

Clone library analysis.

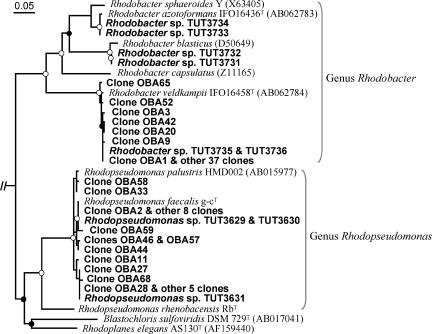

The phylogenetic composition of PPNS bacteria in the colored microbial mats was further studied on the basis of a pufM gene clone library analysis. PCR experiments with the two primer sets resulted in the amplification of pufM gene fragments of an expected size from the bulk DNA extracted from the colored mats (data not shown). For unknown reasons, however, the cloning efficiency was much lower with the PCR products with primers pufM.557F and pufM.750R than with M150f and M572r. Thus, we constructed a clone library only using the products with latter primer set. More than 60 clones from the pufM clone library and the puf gene fragments from representative isolates were sequenced and phylogenetically analyzed. By comparing both nucleotide and translated amino acid sequences of the amplified clones with those retrieved from the databases, all of the clones proved to be derived from PPNS bacteria.

A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree based on nucleotide sequences of pufM genes showed that the clones and the isolates fell into two major clades (Fig. 6). One group was assigned to the genus Rhodopseudomonas, and the other was identified as the genus Rhodobacter. The phylogenetic relationships of pufM genes were consistent with those determined on the basis of 16S rRNA gene sequences of the isolates (cf. Fig. 5), except that the much higher number of clones relevant to Rhodobacter veldkampii were found on the pufM tree. The results of the pufM clone library analysis indicate that the major constituents of the colored mats were species of the genera Rhodobacter and Rhodopseudomonas.

FIG. 6.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree for the biomat clones and the isolates based on nucleotide sequences of pufM genes. The clones from the microbial mats and the isolates are shown in boldface type. Chloroflexus aurantiacus (X07847) was used as an out-group to root the tree. Bar, 5% nucleotide substitutions (Knuc). Accession numbers for the sequences are indicated in parentheses following each strain. Nodes showing a bootstrap percentage of more than 85% and of 60 to 84% (1,000 resamplings) are indicated by open and filled circles, respectively.

Oxygen uptake measurement.

The wastewater in the ditch investigated contained acetate and propionate as the major organic nutrients, which probably served the microbial mats as electron donor and carbon sources. Therefore, oxygen uptake with different lower fatty acids (C2 to C6 acids) was measured using aerobically or semiaerobically grown cells of representative isolates and the authentic strains of PPNS bacteria as well as the freshly collected microbial mats.

In the case of the Rhodobacter strains, it was more difficult to utilize lower fatty acids as the number of carbon atoms increased (Table 2). In particular, the addition of 2 mM caproate resulted in a complete inhibition of endogenous oxygen uptake in the Rhodobacter strains, except that oxygen uptake by Rhodobacter veldkampii strain NBRC 16458T was inhibited only by the addition of propionate. On the other hand, all test strains of Rhodopseudomonas exhibited high rates of oxygen uptake regardless of the carbon number of the substrate. The microbial mat samples displayed substrate uptake patterns similar to those of the Rhodopseudomonas strains. These results indicated that significant differences in the substrate specificity exist between the strains of Rhodobacter and Rhodopseudomonas.

TABLE 2.

Oxygen uptake with different lower fatty acids (C2 to C6) by the strains of PPNS bacteria grown aerobically in darkness and semiaerobically in light and by the swine wastewater microbial mats

| Test organism | Growth conditiona | Oxygen uptake rate (mg min−1 g [dry weight] cells−1) withb:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | Propionate | Butyrate | Valerate | Caproate | ||

| Rhodobacter strains | ||||||

| R. azotoformans KA25Tc | A | 117 ± 14 | −42 ± 10 | −42 ± 10 | −36 ± 1 | −20 ± 4 |

| B | 80 ± 3 | −39 ± 6 | −62 ± 2 | −62 ± 2 | −65 ± 3 | |

| R. blasticus DSM 2131T | A | 100 ± 14 | 33 ± 3 | 35 ± 5 | 36 ± 23 | −5 ± 1 |

| B | 78 ± 8 | 56 ± 11 | 49 ± 13 | 34 ± 10 | −27 ± 15 | |

| R. veldkampii NBRC 16458T | A | 308 ± 20 | −19 ± 9 | 191 ± 11 | 203 ± 18 | 194 ± 12 |

| B | 31 ± 9 | −24 ± 10 | 46 ± 9 | 46 ± 9 | 79 ± 11 | |

| Rhodobacter sp. strain TUT3731 | A | 93 ± 10 | −45 ± 8 | 10 ± 2 | −20 ± 7 | −36 ± 7 |

| B | 65 ± 5 | 36 ± 8 | 10 ± 4 | −21 ± 3 | −16 ± 4 | |

| Rhodobacter sp. strain TUT3733 | A | 130 ± 16 | 17 ± 8 | 15 ± 1 | −88 ± 8 | −75 ± 9 |

| B | 137 ± 14 | 70 ± 6 | 42 ± 6 | −44 ± 9 | −79 ± 7 | |

| Rhodopseudomonas strains | ||||||

| R. palustris ATCC 17001T | A | 485 ± 14 | 395 ± 7 | 330 ± 15 | 430 ± 8 | 396 ± 7 |

| B | 428 ± 6 | 421 ± 6 | 327 ± 8 | 340 ± 11 | 251 ± 11 | |

| Rhodopseudomonas sp. strain TUT3630 | A | 288 ± 16 | 337 ± 15 | 271 ± 21 | 340 ± 4 | 226 ± 5 |

| B | 433 ± 48 | 361 ± 41 | 377 ± 34 | 361 ± 41 | 332 ± 33 | |

| Rhodopseudomonas sp. strain TUT3631d | B | 211 ± 16 | 23 ± 8 | 268 ± 18 | 84 ± 7 | 272 ± 22 |

| Microbial matse | 123 ± 21 | 136 ± 21 | 91 ± 12 | 106 ± 13 | 73 ± 8 | |

A, aerobic, dark; B, semiaerobic, light.

Negative values indicate the degree of inhibition of the endogenous oxygen uptake.

The data were based on information from our previous study (39).

Only cultures grown semiaerobically in the light were tested because of no growth at full atmospheric oxygen tension.

The freshly collected microbial mats were used for oxygen uptake assays.

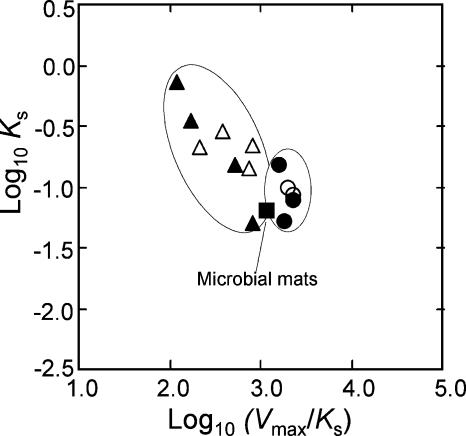

Kinetics of acetate utilization.

Since acetate was a major organic compound in the ditch wastewater as described above, a kinetic analysis of the utilization of acetate by the microbial mats and cultures of the PPNS bacteria was performed to better understand their responses to nutrient gradients. The Michaelis-Menten parameters, Ks and Vmax, calculated from the oxygen uptake rates with acetate are summarized in Table 3. The main difference between the two generic groups of the PPNS bacteria was that the affinity for acetate was higher in the Rhodopseudomonas strains than in the Rhodobacter strains. The microbial mats had a high affinity for acetate, similar to that of the Rhodopseudomonas species. Also, the Vmax of oxygen uptake seemed to be higher in the Rhodopseudomonas strains than in the Rhodobacter strains, although this property varied markedly among the Rhodobacter strains of different origins.

TABLE 3.

Kinetic analysis of oxygen uptake with acetate as the substrate in the strains of PPNS bacteria grown aerobically in darkness and semiaerobically in light and by the swine wastewater microbial mats

| Test organism | Growth conditiona | Ks (mM) | Vmax (mg O2 min−1 g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhodobacter strains | |||

| R. blasticus DSM 2131T | A | 1.6 | 110 |

| B | 0.73 | 90 | |

| R. azotoformans KA25Tb | A | 0.17 | 180 |

| B | 0.17 | 160 | |

| R. veldkampii NBRC 16458T | A | 0.38 | 720 |

| B | 0.051 | 70 | |

| Rhodobacter sp. strain TUT3731 | A | 0.38 | 110 |

| B | 0.35 | 70 | |

| Rhodobacter sp. strain TUT3733 | A | 0.38 | 230 |

| B | 0.15 | 110 | |

| Rhodopseudomonas strains | |||

| R. palustris ATCC 17001T | A | 0.14 | 510 |

| B | 0.077 | 390 | |

| Rhodopseudomonas sp. strain TUT3630 | A | 0.19 | 270 |

| B | 0.15 | 480 | |

| Rhodopseudomonas sp. strain TUT3631c | B | 0.053 | 200 |

| Microbial matsd | 0.064 | 140 |

A, aerobic, dark; B, semiaerobic, light.

The data were based on information from our previous study (39).

Only cultures grown semiaerobically in the light were tested because of no growth at full atmospheric oxygen tension.

The freshly collected microbial mats were used for oxygen uptake assays.

The Vmax/Ks value has been recognized as an important index for the evaluation of enzymatic reactions (14). When the Ks values and the Vmax/Ks ratios for semiaerobic light-grown cells obtained in this study and previously (39) were shown as a two-dimensional plot, the differences in kinetic properties between the test strains of Rhodobacter and Rhodopseudomonas became clearer (Fig. 7). The microbial mats were more similar to the group of the Rhodopseudomonas strains in the kinetic patterns.

FIG. 7.

Relationship between the Ks values and the Vmax/Ks ratios for the PPNS bacteria and microbial mats. The values for the Rhodopseudomonas strains obtained from our previous study (39) and those isolated from the microbial mats in this study are indicated by the open triangles and filled triangles, respectively. The filled circles and open circles indicate the values for the Rhodobacter strains from the previous study and those from the microbial mats, respectively. The solid square represents the value for the microbial mats.

DISCUSSION

Although PPNS bacteria were occasionally found in a laminated microbial mat dominated by cyanobacteria (27, 36), there has been no definite information about the development of microbial mats or biofilms fully dominated by PPNS bacteria. To our knowledge, this is the first report describing colored microbial mats mainly composed of PPNS bacteria. The colored microbial mats we studied were characterized by the predominance of rod-shaped cells containing internal membranes of the lamellar type and BChl a and carotenoids of the spirilloxanthin series as the major photopigments. The second most common morphotype found in the biomats was that of oval cells with vesicular intracytoplasmic membranes. These results as well as the quinone profile data indicate that the phototrophic alphaproteobacteria of the genera Rhodobacter and Rhodopseudomonas were the major constituents of the colored microbial mats. In agreement with these phenotypic data, the phylogenetic analysis of the isolates of PPNS bacteria based on 16S rRNA gene sequences and the pufM clone library analysis have provided unequivocal evidence for the predominance of the phototrophs belonging to the genera Rhodopseudomonas and Rhodobacter.

The new isolates of PPNS bacteria from the microbial mats are phylogenetically closely related to one of the previously known species of Rhodobacter and Rhodopseudomonas (i.e., Rhodobacter azotoformans, Rhodobacter blasticus, Rhodobacter veldkampii, and Rhodopseudomonas faecalis). To date, these species and similar organisms have been isolated mainly from wastewater and polluted environments such as photosynthetic sludge processes (24, 39), swine waste lagoons (11), anaerobic reactors receiving chicken feces (52), and eutrophic freshwater (12, 17). Therefore, there is general agreement between the previous results and ours regarding the relationship between the phylogenetic composition and habitats of PPNS bacteria. More detailed phenotypic and genotypic studies should elucidate the exact taxonomic positions of the isolates at the species level.

Since the ditch investigated is a shallow and water-flowing habitat and allows active mixing with air, the microbial mats therein are possibly exposed to high DO tension. However, microscopic and spectroscopic studies provided evidence that anoxygenic phototrophic growth was occurring in the microbial mats. Probably, a sharp DO gradient takes place in the microbial mats, and the DO concentration is suitable for aerobic growth in the surface of the biomats but is low enough to allow anoxygenic photosynthesis from its core to the bottom. It has been shown that phototrophically grown cells of Rhodobacter capsulatus increase respiratory activity in response to small amounts of oxygen (10). Such a physiological versatility of PPNS bacteria enables them to perform both aerobic respiration and photosynthesis with a sharp DO gradient. The swine wastewater contained a relatively high concentration of sulfate but did not have a sulfide odor, suggesting that the ditch was not under conditions favorable for growth of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Consequently, the availability of reduced forms of sulfur required for full growth of the phototrophic sulfur bacteria was quite low. This is a plausible reason why the PPNS bacteria rather than the phototrophic sulfur bacteria are able to form colored microbial mats in the ditch.

The swine wastewater studied contains acetate and propionate as the major organic nutrients, which seem to be the main carbon sources for the development of the ditch microbial mats. In wastewater environments, high concentrations of lower fatty acids as usable substrates stimulate the proliferation of PPNS bacteria (23, 25, 39), occasionally resulting in the formation of colored blooms (11). However, the results of oxygen uptake assays in this study showed that members of the genus Rhodopseudomonas have a wider spectrum of lower-fatty-acid utilization than those of the geneus Rhodobacter. Comparative kinetic analysis of oxygen uptake with acetate revealed that the Rhodopseudomonas strains had lower Ks and higher Vmax for acetate than did the Rhodobacter strains. Similar results have been obtained with Rhodobacter and Rhodopseudomonas strains isolated from wastewater treatment plants (39). Therefore, the versatility and flexibility with respect to the utilization of lower fatty acids provide Rhodopseudomonas species with a competitive advantage over Rhodobacter species. This is a possible explanation for the superior occurrence of Rhodopseudomonas species in the ditch microbial mats.

Since the microbial mats were dense cell aggregates with a gelatinous matrix, the involvement of extracellular polymeric substances in the biomat formation is a subject of major concern. Interestingly, most Rhodobacter strains isolated from the microbial mats exhibit flocculated growth, unlike the authentic strains of these genera used for comparison in this study. Therefore, one can assume that the capacity of the PPNS bacteria for floc formation with the concomitant production of extracellular polymeric substances is a key factor in stabilizing them in the microbial mats. Although there is only scattered information about floc formation and extracellular polymer production by phototrophic bacteria, it has been shown that some Rhodovulum strains produce extracellular DNA and RNA when they exhibit flocculating growth (5, 48). The involvement of DNA as one of extracellular polymeric substances in bacterial flocculation (41) and biofilm formation (2, 43) has been well documented. Our concurrent study has shown that the cell aggregates of the Rhodobacter isolates are susceptible to DNase I treatment (unpublished data), and further study on this interesting phenomenon is in progress.

In conclusion, our polyphasic approach using the culture-independent biomarker and molecular techniques and conventional microbiological methods clearly demonstrate that the colored microbial mats naturally occurring in the swine wastewater ditch were dominated by the PPNS bacteria of Rhodopseudomonas and Rhodobacter species. The microbial mats with the PPNS bacteria possibly contribute to the degradation of lower fatty acids in the swine wastewater, although the ecological roles of the two generic groups of phototrophs may differ at different tropic levels. PPNS bacteria have been shown to play primary roles in wastewater treatment processes loaded with high concentrations of lower fatty acids (23, 25, 32, 39). The results of this study should help toward the design of an optimal wastewater treatment process using PPNS bacteria and toward its application to the purification of highly concentrated organic wastewaters, including swine wastewater.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Oba farm, Shizuoka, Japan, for providing us with mat samples. We also thank Keiko Okamura for sequencing of the Rhodopseudomonas rhenobacensis pufM gene.

This work was carried out as a part of the 21st Century COE Program “Ecological Engineering and Homeostatic Human Activities” founded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achenbach, L. A., J. Carey, and M. T. Madigan. 2001. Photosynthetic and phylogenetic primers for detection of anoxygenic phototrophs in natural environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2922-2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allesen-Holm, M., K. B. Barken, L. Yang, M. Klausen, J. S. Webb, S. Kjelleberg, S. Molin, M. Givskov, and T. Tolker-Nielsen. 2006. A characterization of DNA release in Pseudomonas aeruginosa cultures and biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 59:1114-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Public Health Association. 1995. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 19th ed. American Public Health Association, Washington, D.C.

- 5.Ando, T., H. Suzuki, S. Nishimura, T. Tanaka, A. Hiraishi, and Y. Kikuchi. 2006. Characterization of extracellular RNAs produced by the marine photosynthetic bacterium Rhodovulum sulfidophilum. J. Biochem. 139:805-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beja, O., M. T. Suzuki, J. F. Heidelberg, W. C. Nelson, C. M. Preston, T. Hamada, J. A. Eisen, C. M. Fraser, and E. F. DeLong. 2002. Unsuspected diversity among marine aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs. Nature 415:630-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castenholz, R. W., and B. K. Pierson. 1995. Ecology of thermophilic anoxygenic phototrophs, p. 87-103. In R. E. Blankenship, M. T. Madigan, and C. E. Bauer (ed.), Anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 8.Clayton, R. K. 1963. Toward the isolation of a photochemical reaction center in Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 75:312-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper, D. E., M. B. Rands, and C.-P. Woo. 1975. Sulfide reduction in fellmongery effluent by red sulfur bacteria. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 47:2088-2100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox, J. C., J. T. Beatty, and J. L. Favinger. 1983. Increased activity of respiratory enzymes from photosynthetically grown Rhodopseudomonas capsulata in response to small amounts of oxygen. Arch. Microbiol. 134:324-328. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Do, Y. S., T. M. Schmidt, J. A. Zahn, E. S. Boyd, A. Mora, and A. A. DiSpirito. 2003. Role of Rhodobacter sp. strain PS9, a purple non-sulfur photosynthetic bacterium isolated from an anaerobic swine waste lagoon, in odor remediation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1710-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckersley, K., and C. S. Dow. 1980. Rhodopseudomonas blastica sp. nov.: a member of the Rhodospirillaceae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 119:465-473. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fersht, A. 1977. Enzyme structure and mechanism. Freeman, New York. N. Y.

- 15.Folsom, B. R., L. J. Chapman, and P. H. Pritchard. 1990. Phenol and trichloroethylene degradation by Pseudomonas cepacia G4: kinetics and interactions between substrates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1279-1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanada, S. 2003. Filamentous anoxygenic phototrophs in hot springs. Microbes Environ. 18:51-61. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen, T. A., and J. F. Imhoff. 1985. Rhodobacter veldkampii, a new species of phototrophic purple nonsulfur bacteria. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 35:115-116. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiraishi, A. 1992. Direct automated sequencing of 16S rDNA amplified by polymerase chain reaction from bacterial cultures without DNA purification. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 15:210-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiraishi, A. 1999. Isoprenoid quinones as biomarkers of microbial populations in the environment. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 88:415-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiraishi, A., M. Iwasaki, and H. Shinjo. 2000. Terminal restriction pattern analysis of 16S rRNA genes for the characterization of bacterial communities of activated sludge. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 90:148-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiraishi, A., Y. Kamagata, and K. Nakamura. 1995. Polymerase chain reaction amplification and restricted fragment length polymorphism analysis of 16S rRNA gene from methanogens. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 79:523-529. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiraishi, A., and H. Kitamura. 1984. Distribution of phototrophic purple nonsulfur bacteria in activated sludge systems and other aquatic environments. Bull. Jpn. Soc. Sci. Fish. 50:1929-1937. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiraishi, A., Y. Morishima, and H. Kitamura. 1991. Use of isoprenoid quinone profiles to study the bacterial community structure and population dynamics in the photosynthetic sludge system. Water Sci. Technol. 23:937-945. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiraishi, A., K. Muramatsu, and K. Urata. 1995. Characterization of new denitrifying Rhodobacter strains isolated from photosynthetic sludge for wastewater treatment. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 79:39-44. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiraishi, A., J. L. Shi, and H. Kitamura. 1989. Effects of organic nutrient strength on the purple nonsulfur bacterial content and metabolic activity of photosynthetic sludge for wastewater treatment. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 68:269-276. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiraishi, A., and Y. Ueda. 1995. Isolation and characterization of Rhodovulum strictum sp. nov. and some other purple nonsulfur bacteria from colored blooms in tidal and seawater pools. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:319-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirschler-Rea, A., R. Matheron, C. Riffaud, S. Moune, C. Eatock, R. A. Herbert, J. C. Willison, and P. Caumette. 2003. Isolation and characterization of spirilloid purple phototrophic bacteria forming red layers in microbial mats of Mediterranean salterns: description of Halorhodospira neutriphila sp. nov. and emendation of the genus Halorhodospira. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:153-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imhoff, J. F., A. Hiraishi, and J. Süling. 2005. Anoxygenic phototrophic purple bacteria, p. 119-132. In D. J. Brenner, N. R. Krieg, J. T. Staley, and G. M. Garrity (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 2nd ed., vol. 2. The Proteobacteria, part A, introductory essays. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwasaki, M., and A. Hiraishi. 1998. A new approach to numerical analyses of microbial quinone profiles in the environment. Microbes Environ. 13:67-76. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Javor, B. J., and R. W. Castenholtz. 1981. Laminated microbial mats Laguna Guerroro Negro, Mexico. Geomicrobiol. J. 2:237-274. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimura, M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitution through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitamura, H., K. Kurosawa, and M. Kobayashi. 1980. Treatment of human wastes using a photosynthetic bacterial method (PSB method), p. 343-346. In C. Po (ed.), Animal waste treatment and utilization. Council for Agricultural Planning and Development, Taipei, Taiwan.

- 33.Madigan, M. T. 2003. Anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria from extreme environments. Photosyn. Res. 76:157-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marmur, J. 1961. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from micro-organisms. J. Mol. Biol. 3:208-218. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuzawa, Y., T. Kanbe, J. Suzuki, and A. Hiraishi. 2000. Ultrastructure of the acidophilic aerobic photosynthetic bacterium Acidophilium rubrum. Curr. Microbiol. 40:398-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehrabi, S., U. M. Ekanemesang, F. O. Aikhionbare, K. S. Kimbro, and J. Bender. 2001. Identification and characterization of Rhodopseudomonas spp., a purple non-sulfur bacterium from microbial mats. Biomol. Eng. 18:49-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyoshi, M. 1897. Studien über die Schwefelrasenbildung und die Schwefelbakterien der Thermen von Yumoto bei Nikko. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Parasiten Infek. Abt. 2:526-527. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nübel, U., M. M. Bateson, M. T. Madigan, M. Kühl, and D. M. Ward. 2001. Diversity and distribution in hypersaline microbial mats of bacteria related to Chloroflexus spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4365-4371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okubo, Y., H. Futamata, and A. Hiraishi. 2005. Distribution and capacity for utilization of lower fatty acids of phototrophic purple nonsulfur bacteria in wastewater environments. Microbes Environ. 20:135-143. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakka, K., and H. Takahashi. 1981. DNA as a flocculation factor in Pseudomonas sp. Agric. Biol. Chem. 45:2869-2876. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sletten, O., and R. H. Singer. 1971. Sulfur bacteria in red lagoons. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 43:2118-2122. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steinberger, R. E., and P. A. Holden. 2005. Extracellular DNA in single- and multiple-species unsaturated biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5404-5410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stolz, J. F. 1990. Distribution of phototrophic microbes in the flat microbial mat at Laguna Figueroa, Baja California, Mexico. Biosystems 23:345-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taga, N. 1967. Microbial coloring of sea water in tidal pool, with special reference to massive development of photosynthetic bacteria. Inf. Bull. Planktol. Jpn. Commemorative issue for Dr. Y. Matsue, p. 219-229.

- 46.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vila, X., R. Guyoneaud, X. P. Cristina, J. B. Figueras, and C. A. Abella. 2002. Green sulfur bacteria from hypersaline Chiprana Lake (Monegros, Spain): habitat description and phylogenetic relationship of isolated strains. Photosyn. Res. 71:165-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watanabe, M., K. Sasaki, Y. Nakashimada, T. Kakizono, N. Noparatnaraporn, and N. Nishio. 1998. Growth and flocculation of a marine photosynthetic bacterium Rhodovulum sp. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 50:682-691. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weisburg, W. G., S. M. Barns, D. A. Pelletier, and D. J. Lane. 1991. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 173:697-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wenke, T. L., and J. C. Vogt. 1981. Temporal changes in a pink feedlot lagoon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 41:381-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yutin, N., M. T. Suzuki, and O. Beja. 2005. Novel primers reveal wider diversity among marine aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8958-8962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang, D., H. Yang, Z. Huang, W. Zhang, and S. J. Liu. 2002. Rhodopseudomonas faecalis sp. nov., a phototrophic bacterium isolated from an anaerobic reactor that digests chicken faeces. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:2055-2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]