Abstract

To evaluate whether C. perfringens can be used as a model organism for studying the sporulation process in other clostridia, C. perfringens spo0A mutant IH101 was complemented with wild-type spo0A from four different Clostridium species. Wild-type spo0A from C. acetobutylicum or C. tetani, but not from C. botulinum or C. difficile, restored sporulation and enterotoxin production in IH101. The ability of spo0A from C. botulinum or C. difficile to complement the lack of spore formation in IH101 might be due, at least in part, to the low levels of spo0A transcription and Spo0A production.

Under environmental stress, Bacillus and Clostridium species undergo asymmetric cell division, or sporulation (13). The initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis is controlled by the phosphorylation state of the sporulation transcription factor, Spo0A (5). As a member of the response regulator, Spo0A orchestrates changes in gene transcription during the transition from growth to sporulation (13). Counterparts of B. subtilis Spo0A have been detected in many other Bacillus and Clostridium species (3, 4, 8, 16), and recent studies have presented evidence that (i) Clostridium acetobutylicum Spo0A transcriptionally activates genes for sporulation and solvent formation (8, 9, 14) and (ii) expression of spo0A is essential for the formation of endospores and the production of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin (CPE) by C. perfringens type A (10).

Although the processes of sporulation in Bacillus and Clostridium species are assumed to be similar, recent genome sequencing has identified some important differences. One example of the difference is that the phosphorelay pathway required to activate Spo0A in Bacillus species is absent in Clostridium species (4, 8, 16, 17). To gain insight into the fundamental differences between the sporulation mechanisms of Clostridium and Bacillus species, it is essential to perform molecular analyses of sporulation-specific genes in clostridia. Research on many pathogenic Clostridium species, such as C. botulinum, C. difficile, and C. tetani, is hampered by the lack of genetic tools to introduce knockout mutations into the genome. However, mutagenesis is possible in C. perfringens. Therefore, we used C. perfringens as a model organism with which to study the sporulation process in other pathogenic clostridia. We hypothesized that if the mechanism of Spo0A-regulated sporulation in C. perfringens is similar to that in other Clostridium species, then the lack of endospore formation in a spo0A knockout mutant of C. perfringens should be complemented by wild-type spo0A from other clostridia. To evaluate this hypothesis, in this study we (i) constructed complementing plasmids carrying wild-type spo0A from C. acetobutylicum, C. botulinum, C. difficile, or C. tetani, (ii) introduced these complementing plasmids into a C. perfringens spo0A knockout mutant, and (iii) evaluated the sporulation capabilities of the complemented strains.

The wild-type spo0A open reading frame (ORF) plus a ∼400-bp upstream sequence of C. botulinum (strain Hall), C. difficile (strain 630), and C. tetani (CN655) were PCR amplified from each genomic DNA using primer pairs CPP61-CPP62, CPP51-CPP52, and CPP59-CPP60, respectively (Table 1). The spo0A ORF and ∼400-bp upstream region of C. acetobutylicum were PCR amplified from pMSPOA (Table 2) using primers CPP70 and CPP71 (Table 1). The amplified PCR products from C. acetobutylicum, C. botulinum, C. difficile, and C. tetani were then cloned into pCR-XL-TOPO (Invitrogen) to create pIH1, pIH3, pIH8, and pIH13, respectively (Table 2). The DNA inserts in these plasmids were sequenced to ensure that no mutation was introduced during PCR amplification. KpnI/XhoI fragments of pIH1, pIH3, pIH8, and pIH13 were then recloned into the KpnI/SalI sites of the Escherichia coli-C. perfringens shuttle vector pJIR751 (2) to create complementing plasmids pIH2, pIH4, pIH9, and pIH14, respectively (Table 2). The complementing plasmids were then introduced into the C. perfringens spo0A mutant IH101 by electroporation (7). PCR analyses with spo0A-specific internal primers (Table 1) from each Clostridium species confirmed the presence of wild-type spo0A in IH101 transformants (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) | Positiona | Region(s) amplified |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPP29 | GAGTGGATGTTAAAAGATGCA | −207 | C. perfringens spo0A promoter region |

| CPP96 | ATTCCTTCATATGTTTCTCTCC | +7 | |

| CPP51 | CAGAGCTAGGTATAAGTGGT | −498 | C. difficile spo0A plus ∼400-bp upstream region |

| CPP52 | CCCTAGTGGTTATACCGTTT | +984 | |

| CPP59 | GGTGGAATAGTTCAAGGAATG | −316 | C. tetani spo0A plus ∼400-bp upstream region |

| CPP60 | AAACCATTGGTACGCCTACT | +857 | |

| CPP61 | GGATGCAGGCATATTAGA | −457 | C. botulinum spo0A plus ∼400-bp upstream region |

| CPP62 | AGCCAATGTACAAAAGGC | +950 | |

| CPP68 | CAGGAATTGCAAAGGATGGATTGGAAGC | +100 | C. perfringens spo0A internal fragment |

| CPP69 | GGCATGTATTTGTCCTCTTCCCCAAG | +719 | |

| CPP70 | GGAGTTTATATTGAATGGATCCTTAAAAG | −406 | C. acetobutylicum spo0A plus ∼400-bp upstream region |

| CPP71 | TTACTATTCCTTGGTGATCATTAAAGAAA | +1119 | |

| CPP72 | GGCATAGCTAAGGATGGAATTGAAGC | +185 | C. difficile spo0A internal fragment |

| CPP73 | CCTCTACTCCATGCAACCTCTATTGC | +772 | |

| CPP74 | GGTATTGGAAAAGATGGAGTAGAGGC | +120 | C. tetani spo0A internal fragment |

| CPP75 | GCTCTTTCAACTCTACTAGCGGTGG | +677 | |

| CPP76 | GGTATAGCTAATGATGGAGTAGAGGC | +102 | C. botulinum spo0A internal fragment |

| CPP77 | GTCTCGACTTGACCTCTTGACCAAG | +710 | |

| CPP93 | GGAGAGTAGTTCATATGG | −15 | C. botulinum spo0A ORF with NdeI site at ATG |

| CPP62 | AGCCAATGTACAAAAGGC | +950 | |

| CPP94 | TGTTTTCATATGGGGGGA | −9 | C. difficile spo0A ORF with NdeI site at ATG |

| CPP52 | CCCTAGTGGTTATACCGTTT | +984 | |

| CPP102 | GAAGAGAAAGAGGCAAGCTTTGCAG | +421 | C. acetobutylicum spo0A internal fragment |

| CPP103 | GTTTCAACCTGTCCACGTGACCAT | +735 | |

| CPP182 | CCATATGGGATACATGAAATAGGAGTAC | +498 | C. difficile spo0A N-terminal domain |

| CPP183 | CTTGTAATACGCATTTATAGCCAATGCC | +884 | |

| CPP184 | CCATATGGGATACATGAAATAGGCGT | +498 | C. botulinum spo0A N-terminal domain |

| CPP185 | GCACTTAAGCCAATGTACAAAAGGCA | +957 | |

| CPP186 | TGGTTAATAAACCTGAAGTAGGATATG | −244 | C. perfringens spo0A C-terminal domain plus promoter region |

| CPP193 | CCATATGGAGTTATTTCAACCTCTAA | +500 |

The nucleotide position numbering begins from the first codon and refers to the relevant position within the respective spo0A gene sequence.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

C. perfringens strains

|

||||

| SM101 | Electroporatable derivative of a food poisoning type A isolate, NCTC8798 | 19 | ||

| IH101 | spo0A knockout mutant derivative of SM101 | 10 | ||

| IH101(pMRS123) | IH101 complemented with wild-type C. perfringens spo0A | 10 | ||

| Plasmids

|

||||

| pJIR751 | C. perfringens-E. coli shuttle vector; Emr | 2 | ||

| pMSPOA | C. acetobutylicum spo0A and its natural promoter inserted into pIMP1 | 1 | ||

| pIH1 | A 1,527-bp DNA fragment containing the C. acetobutylicum spo0A ORF and a ∼400-bp upstream region was cloned into pCR-XL-TOPO | This study | ||

| pIH2 | A ∼1.6-kb KpnI/XhoI fragment from pIH1 was cloned into KpnI/SalI sites of pJIR751 | This study | ||

| pIH3 | A 1,407-bp DNA fragment containing the C. botulinum spo0A ORF and a ∼400-bp upstream region was cloned into pCR-XL-TOPO | This study | ||

| pIH4 | A ∼1.5-kb KpnI/XhoI fragment from pIH3 was cloned into KpnI/SalI sites of pJIR751 | This study | ||

| pIHOAPRO | A 204-bp DNA fragment containing the C. perfringens spo0A upstream region was cloned into pCR-TOPO-XL | This study | ||

| pIH5 | A 964-bp DNA fragment containing the C. botulinum spo0A ORF with an NdeI site inserted just before ATG was cloned into pCR-XL-TOPO | This study | ||

| pIH6 | A ∼1.0-kb NdeI/PstI fragment from pIH5 was cloned into pIHOAPRO | This study | ||

| pIH7 | A ∼1.2-kb KpnI/XhoI fragment from pIH6 was cloned into KpnI/SalI sites of pJIR751 | This study | ||

| pIH8 | A 1,285-bp DNA fragment containing the C. difficile spo0A ORF and a ∼400-bp upstream region was cloned into pCR-XL-TOPO | This study | ||

| pIH9 | A ∼1.3-kb KpnI/XhoI fragment from pIH8 was cloned into KpnI/SalI sites of pJIR751 | This study | ||

| pIH10 | An 883-bp DNA fragment containing the C. difficile spo0A ORF with an NdeI site inserted just before ATG was cloned into pCR-XL-TOPO | This study | ||

| pIH11 | A 0.9-kb NdeI/PstI fragment from pIH10 was cloned into pIHOAPRO | This study | ||

| pIH12 | A ∼1.1-kb KpnI/XhoI fragment from pIH11 was cloned into KpnI/SalI sites of pJIR751 | This study | ||

| pIH13 | A 1,174-bp DNA fragment containing the C. tetani spo0A ORF and a ∼400-bp upstream region was cloned into pCR-XL-TOPO | This study | ||

| pIH14 | A ∼1.2-kb KpnI/XhoI fragment from pIH13 was cloned into KpnI/SalI sites of pJIR751 | This study | ||

| pIH15 | A 744-bp DNA fragment containing the C. perfringens spo0A promoter region and the C-terminal domain with an Nde1 site was cloned into pCR-XL-TOPO | This study | ||

| pIH16 | A 459-bp DNA fragment containing the C. botulinum spo0A C-terminal domain with an Nde1 site was cloned into pCR-XL-TOPO | This study | ||

| pIH17 | A 386-bp DNA fragment containing the C. difficile spo0A C-terminal domain with an NdeI site was cloned into pCR-XL-TOPO | This study | ||

| pIH18 | A ∼0.8-kb Nde1/XbaI fragment from pIH15 was cloned into SpeI/NdeI sites of pIH16 | This study | ||

| pIH19 | A ∼1.2-kb KpnI/XbaI fragment from pIH18 was cloned into KpnI/XbaI sites of pJIR751 | This study | ||

| pIH20 | A ∼0.8-kb NdeI/XbaI fragment from pIH15 was cloned into SpeI/NdeI sites of pIH17 | This study | ||

| pIH21 | A ∼1.1-kb KpnI/XbaI fragment from pIH20 was cloned into KpnI/XbaI sites of pJIR751 | This study | ||

Having obtained evidence for successful construction of complemented strains, we compared the sporulation capabilities of the complemented strains to that of an spo0A mutant as previously described (10). As expected, IH101 exhibited significantly decreased production of heat-resistant spores compared to wild-type SM101 (Table 3) (10), and this lack of ability of the spo0A mutant to form heat-resistant spores could be complemented with recombinant plasmid pMRS123, carrying wild-type spo0A from C. perfringens. When similar experiments were performed with our newly constructed complemented strains, IH101 complemented with the recombinant plasmid pIH14 produced spores at a level similar to that of wild-type SM101 (Table 3). A lower level of heat-resistant spore formation was also observed with IH101 complemented with the recombinant plasmid pIH2 (Table 3). However, a recombinant plasmid carrying wild-type spo0A either from C. botulinum (pIH4) or from C. difficile (pIH9) did not complement the mutation in IH101 (Table 3). Collectively, these results indicated that spo0A from C. acetobutylicum or C. tetani, but not from C. botulinum or C. difficile, was able to complement the sporulation defects of the C. perfringens spo0A mutant IH101.

TABLE 3.

Sporulation of complemented strains grown in DS medium

| Strain | Concn (CFU/ml)a of:

|

Frequencyd | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viable cellsb | Sporesc | ||

| SM101 | 3.4 × 107 | 3.2 × 107 | 0.94 |

| IH101 | 5.1 × 107 | 4.0 × 101 | 7.8 × 10−7 |

| IH101(pMRS123) | 3.3 × 107 | 2.6 × 107 | 0.79 |

| IH101(pIH2) | 4.2 × 107 | 3.6 × 106 | 0.09 |

| IH101(pIH4) | 2.4 × 107 | 1.0 × 101 | 4.1 × 10−7 |

| IH101(pIH9) | 3.1 × 107 | 1.0 × 101 | 3.1 × 10−7 |

| IH101(pIH14) | 5.6 × 107 | 5.5 × 107 | 0.98 |

| IH101(pIH7) | 2.6 × 107 | 1.0 × 101 | 3.8 × 10−7 |

| IH101(pIH12) | 2.8 × 107 | 2.4 × 102 | 8.6 × 10−6 |

| IH101(pIH19) | 2.6 × 107 | 3.5 × 102 | 1.3 × 10−5 |

| IH101(pIH21) | 1.2 × 107 | 3.3 × 102 | 2.9 × 10−5 |

Results shown are based on at least three independent determinations for each experimental parameter for each culture.

Total CFU per milliliter present in each culture before heat treatment.

Total CFU per milliliter present in each culture after heat treatment at 80°C for 20 min.

Calculated as the ratio of the number of spores to the number of viable cells.

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analyses were then performed to investigate whether the inability of spo0A from C. botulinum or C. difficile to restore spore formation in IH101 was a function of the lack of spo0A expression. Total RNA was isolated from Duncan-Strong (DS) cultures of C. perfringens strains, and spo0A-specific mRNA was detected using spo0A-specific primers (Table 1) as previously described (7, 10). A spo0A-specific RT-PCR product was obtained from RNA of IH101(pIH9), indicating that C. difficile spo0A can be expressed in C. perfringens. However, no spo0A-specific RT-PCR product was obtained from RNA of IH101(pIH4), suggesting that C. botulinum spo0A was not transcribed in C. perfringens.

Next, we examined whether differences in the promoter region were responsible for the lack of C. botulinum spo0A expression. We constructed a recombinant plasmid, pIH7, carrying C. botulinum spo0A fused with the spo0A promoter region from C. perfringens (Table 2). As a control, pIH12, which carries C. difficile spo0A fused with the C. perfringens spo0A promoter, was also constructed (Table 2). In addition, since a recent study (18) showed that a chimeric Spo0A, containing the response regulator domain of B. subtilis Spo0A fused with the DNA-binding domain of C. botulinum Spo0A, could partially restore spore formation in a B. subtilis spo0A mutant, we constructed similar chimeric plasmids: plasmids pIH19 and pIH21, carrying the C. perfringens Spo0A response regulator domain fused to the DNA-binding domain of Spo0A from C. botulinum and C. difficile, respectively (Table 2). Nucleotide sequencing confirmed that no PCR-generated mutation was introduced during PCR amplification of the inserts. The recombinant fusion plasmids, pIH7, pIH12, pIH19, and pIH21, were introduced into IH101 by electroporation. Our RT-PCR analyses detected spo0A-specific RT-PCR products from RNAs of all four transformants, indicating that both wild-type and chimeric spo0A of C. botulinum and C. difficile were expressed in the C. perfringens spo0A mutant when placed under the control of the C. perfringens spo0A promoter. However, when the spore-forming capabilities of these transformants were compared with that of their host strain, IH101, no refractile endospores were detected after 8 h of growth in DS medium and no significant increase in heat-resistant spore formation was observed (Table 3.)

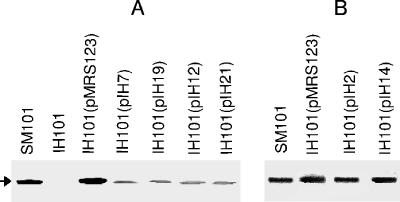

To determine if the inability of both wild-type and chimeric spo0A from C. botulinum and C. difficile to restore spore formation in IH101 resulted from a lack of Spo0A production, Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (18). Briefly, C. perfringens strains were grown in DS medium and sonicated until >95% of cells were lysed, and then each culture lysate was analyzed for the presence of Spo0A by using an antibody against B. subtilis Spo0A. As expected, a Spo0A-specific immunoreactive band was observed in lysates prepared from SM101 and IH101(pMRS123), while no Spo0A-specific band was detected in lysates prepared from spo0A mutant IH101 (Fig. 1A). A Spo0A-specific immunoreactive band was also observed in sporulating culture lysates prepared from IH101 carrying wild-type or chimeric spo0A from C. botulinum or C. difficile, albeit at an intensity lower than those for SM101 and IH101(pMRS123) (Fig. 1A). To ensure that the lower intensity of the Spo0A-specific band observed was not due to a different reactivity to the antibody against Bacillus Spo0A, Western blot analysis of the two complemented strains IH101(pIH2) and IH101(pIH14) was also performed. The Spo0A-specific immunoreactive bands detected for both strains were similar in intensity to those of SM101 and IH101(pMRS123) (Fig. 1B). These results suggested that the inability of the wild-type and chimeric Spo0A from C. botulinum and C. difficile to restore spore formation in the C. perfringens spo0A mutant may be a result of decreased production of Spo0A.

FIG. 1.

Western blot analysis of Spo0A production by wild-type C. perfringens and complemented strains. C. perfringens strains were grown in DS medium and sonicated as described elsewhere (10, 11). An aliquot (20 μl) of each sonicated culture lysate was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by Western blotting with anti-B. subtilis Spo0A antibodies. The blot was subjected to chemiluminescence detection to identify immunoreactive species. (A) Results are shown for control strains SM101 (wild type) and IH101 (spo0A knockout mutant) and for representative complemented strains IH101(pMRS123), IH101(pIH7), IH101(pIH19), IH101(pIH12), and IH101(pIH21). (B) Results are shown for control strains SM101 (wild type) and IH101(pMRS123) and for complemented strains IH101(pIH2) and IH101(pIH14). The arrow on the left of the blot indicates the migration of the Spo0A-specific immunoreactive band.

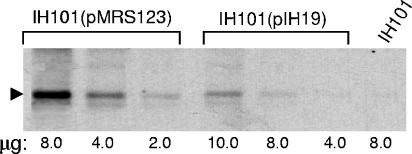

We then performed Northern blot analyses, as previously described (10, 12), to evaluate whether the differential production of Spo0A observed was due to a differential level of spo0A mRNA synthesis. The spo0A transcripts detected for total RNA of IH101 carrying wild-type or chimeric C. botulinum or C. difficile spo0A were similar in intensity to each other but lower in intensity than that of IH101(pMRS123) (Fig. 2) (data not shown). When the relative spo0A mRNA levels were determined by semiquantitative Northern blot analysis, at least a fivefold difference in spo0A transcription was observed between IH101(pMRS123) and the four complementing strains IH101(pIH7), IH101(pIH12), IH101(pIH19), and IH101(pIH21) (Fig. 2) (data not shown). These results suggest that the lower level of Spo0A in IH101 carrying wild-type or chimeric Spo0A from C. botulinum or C. difficile may be a result of a decreased level of spo0A transcription.

FIG. 2.

Comparative expression of spo0A mRNAs from IH101(pIH19) and IH101(pMRS123). Various amounts of RNA, extracted from IH101(pMRS123) and IH101(pIH19) cultures grown in DS medium at 37°C for 6 h as previously described (7, 10), were separated by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel and transferred by Northern blotting. The blots were hybridized with an AlkPhos-labeled spo0A probe, and hybridized probe was then detected by CDPstar chemiluminescence (Amersham Bioscience). The relative levels of spo0A mRNA in IH101(pIH19) were determined from a calibration curve, which was made using various amounts (2.0 to 8.0 μg) of RNA prepared from the high-Spo0A-producing strain IH101(pMRS123). The densitometric analysis was performed on a Macintosh computer using the public domain NIH Image program (developed at the U.S. National Institutes of Health and available on the Internet at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/). The spo0A mRNA-specific band is indicated by an arrow. The various amounts of RNA loaded on the gel are given at the bottom of the blot.

Since CPE is a sporulation-regulated toxin, it was of interest to compare the levels of CPE production in the complemented strains. CPE Western blot analyses (6, 11) detected a ∼35-kDa CPE-specific immunoreactive band in Western blots of lysates prepared from sporulating cultures of complemented strains IH101(pMRS123), IH101(pIH2), and IH101(pIH14) (data not shown). However, no CPE-specific immunoreactivity was detected in lysates prepared from complemented strains carrying wild-type or chimeric spo0A from C. botulinum or C. difficile grown under sporulation conditions (data not shown). Quantitative Western blot analyses (6, 15) showed similar levels of CPE production by complemented strains IH101(pIH14) and IH101(pMRS123) (data not shown). Although IH101(pIH2) produced a slightly smaller amount of CPE than IH101(pIH14) and IH101(pMRS123), this was not due to the influence of either total growth or sporulation (data not shown). Collectively, these results indicated that the lack of CPE production in the C. perfringens spo0A knockout mutant was restored by complementing the mutant with recombinant plasmids carrying wild-type spo0A from C. acetobutylicum or C. tetani but not from C. difficile or C. botulinum.

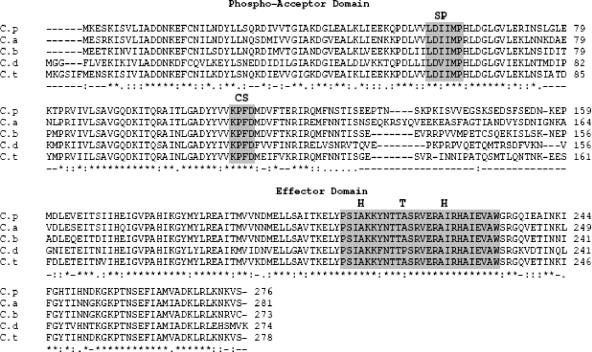

In summary, our results demonstrated that wild-type spo0A from C. acetobutylicum or C. tetani, but not from C. botulinum or C. difficile, restored sporulation and CPE production in a spo0A mutant of C. perfringens. The inability of wild-type and chimeric spo0A from C. botulinum or C. difficile to complement the sporulation defect of the C. perfringens spo0A mutant cannot be explained by the low level of amino acid sequence identity between Spo0A from C. perfringens and Spo0A from C. botulinum or C. difficile. Note that high levels of sequence identity were obtained when the amino acid sequence of Spo0A from C. perfringens was compared with those from C. acetobutylicum (76%), C. botulinum (78%), C. difficile (60%), and C. tetani (76%) (data not shown). The putative phosphorylation site (LDIIMP), the conformational switch region (KPFD), and the helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding motif are also highly conserved in all Clostridium species compared (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of amino acid sequences of phosphoacceptor and effector domains of Spo0A from C. perfringens (C.p), C. acetobutylicum (C.a), C. botulinum (C.b), C. difficile (C.d), and C. tetani (C.t). Asterisks indicate residues that are identical in all five species. Highlighting indicates possible active sites: SP, putative site of phosphorylation; CS, the conformational region; HTH, the helix-turn-helix motif. The deduced amino acid sequences of Spo0A from C. perfringens, C. acetobutylicum, and C. tetani were available on the Entrez Genome website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=Genome). The amino acid sequences of C. botulinum and C. difficile were obtained from the Sanger Institute's website (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/). Amino acid alignment was performed using the ClustalW program and modified with Microsoft PowerPoint.

Our current results suggest that the lack of spore formation in IH101 complemented with spo0A from C. botulinum or C. difficile was due, at least in part, to the lower levels of spo0A transcription and Spo0A production, which were insufficient to initiate sporulation. However, it is not clear why lower levels of the spo0A transcript were detected with constructs where the C. perfringens spo0A promoter region was fused to C. botulinum or C. difficile spo0A. One possible explanation might be the instability of the spo0A transcript. Our results cannot exclude the possibility that certain unidentified amino acid differences within the DNA-binding domain of Spo0A from C. botulinum and C. difficile versus C. perfringens might be crucial for initiation of sporulation. Since a recent study (12) identified inorganic phosphate as an environmental signal for initiation of sporulation in C. perfringens, it is also possible that sporulation signals might be unique to each species and might reflect the environment where they reside (18).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the N. L. Tartar Foundation of Oregon State University and by USDA grant 2002-02281 from the Ensuring Food Safety Research Program (both to M.R.S.).

We are grateful to M. R. Popoff, Institute Pasteur, France, for providing us with genomic DNAs of C. botulinum strain Hall and C. tetani strain CN655 and to J. D. Haraldsen of the Linc Sonenshein lab, Tufts University School of Medicine, for genomic DNA of C. difficile strain 630. We are also grateful to E. T. Papoutsakis, Northwestern University, Illinois, for providing us with pMSPOA. We thank B. A. McClane, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, for providing us with purified CPE and a CPE antibody. We also thank Michael Waters for technical assistance in constructing pIH3 and pIH4 and D. D. Rockey (Oregon State University) for editorial comments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alsaker, K. V., T. R. Spitzer, and E. T. Papoutsakis. 2004. Transcriptional analysis of spo0A overexpression in Clostridium acetobutylicum and its effect on the cell's response to butanol stress. J. Bacteriol. 186:1959-1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bannam, T. L., and J. I. Rood. 1993. Clostridium perfringens-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors that carry single antibiotic resistance determinants. Plasmid 29:233-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, D. P., L. Ganova-Raeva, B. D. Green, S. R. Wilkinson, M. Young, and P. Youngman. 1994. Characterization of spo0A homologues in diverse Bacillus and Clostridium species reveals regions of high conservation within the effector domains. Mol. Microbiol. 14:411-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruggemann, H., et al. 2003. The genome sequence of Clostridium tetani, the causative agent of tetanus disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1316-1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burbulys, D., K. A. Trach, and J. A. Hoch. 1991. The initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis is controlled by a multicomponent phosphorelay. Cell 64:545-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collie, R. E., J. F. Kokai-Kun, and B. A. McClane. 1998. Phenotypic characterization of enteropathogenic Clostridium perfringens isolates from non-food-borne human gastrointestinal diseases. Anaerobes 4:69-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czeczulin, J. R., R. E. Collie, and B. A. McClane. 1996. Regulated expression of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin in naturally cpe-negative type A, B, and C isolates of C. perfringens. Infect. Immun. 64:3301-3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durre, P., and C. Hollergschwandner. 2004. Initiation of endospore formation in Clostridium acetobutylicum. Anaerobes 10:69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris, L. M., N. E. Welker, and E. T. Papoutsakis. 2002. Northern, morphological, and fermentation analysis of spo0A inactivation and overexpression in Clostridium acetobutylicum. J. Bacteriol. 184:3586-3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang, I. H., M. Waters, R. R. Grau, and M. R. Sarker. 2004. Disruption of the gene (spo0A) encoding sporulation transcription factor blocks endospore formation and enterotoxin production in enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens type A. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 233:233-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kokai-Kun, J. F., J. G. Songer, J. R. Czeczulin, F. Chen, and B. A. McClane. 1994. Comparison of Western immunoblots and gene detection assays for identification of potentially enterotoxigenic isolates of Clostridium perfringens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2533-2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Philippe, V. A., M. B. Mendez, I. Huang, L. M. Orsaria, M. R. Sarker, and R. R. Grau. 2006. Inorganic phosphate induces spore morphogenesis and enterotoxin production in the intestinal pathogen Clostridium perfringens. Infect. Immun. 74:3651-3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piggot, P. J., and R. Losick. 2002. Sporulation genes and intercompartmental regulation, p. 483-517. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 14.Ravagnani, A., K. C. B. Jennett, E. Steiner, R. Grunberg, J. R. Jefferies, S. R. Wilkinson, D. I. Young, E. C. Tidswell, D. P. Brown, P. Youngman, J. G. Morris, and M. Young. 2000. Spo0A directly controls the switch from acid to solvent production in solvent-forming clostridia. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1172-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarker, M. R., R. J. Carman, and B. A. McClane. 1999. Inactivation of the gene (cpe) encoding Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin eliminates the ability of two cpe-positive C. perfringens type A human gastrointestinal disease isolates to affect rabbit ileal loops. Mol. Microbiol. 33:946-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimizu, T., K. Ohtani, H. Hirakawa, K. Ohshima, A. Yamashita, T. Shiba, N. Ogasawara, M. Hattori, S. Kuhara, and H. Hayashi. 2002. Complete genome sequence of Clostridium perfringens, an anaerobic flesh-eater. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:996-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stragier, P. 2002. A gene odyssey: exploring the genomes of endospore-forming bacteria, p. 519-525. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 18.Worner, K., H. Szurmant, C. Chiang, and J. A. Hoch. 2006. Phosphorylation and functional analysis of the sporulation initiation factor Spo0A from Clostridium botulinum. Mol. Microbiol. 59:1000-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao, Y., and S. B. Melville. 1998. Identification and characterization of sporulation-dependent promoters upstream of the enterotoxin gene (cpe) of Clostridium perfringens. J. Bacteriol. 180:136-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]