Abstract

We investigated bacterial diversity in different aquatic environments (including marine and lagoon sediments, coastal seawater, and groundwater), and we compared two fingerprinting techniques (terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism [T-RFLP] and automated ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis [ARISA]) which are currently utilized for estimating richness and community composition. Bacterial diversity ranged from 27 to 99 phylotypes (on average, 56) using the T-RFLP approach and from 62 to 101 genotypes (on average, 81) when the same samples were analyzed using ARISA. The total diversity encountered in all matrices analyzed was 144 phylotypes for T-RFLP and 200 genotypes for ARISA. Although the two techniques provided similar results in the analysis of community structure, bacterial richness and diversity estimates were significantly higher using ARISA. These findings suggest that ARISA is more effective than T-RFLP in detecting the presence of bacterial taxa accounting for <5% of total amplified product. ARISA enabled also distinction among aquatic bacterial isolates of Pseudomonas spp. which were indistinguishable using T-RFLP analysis. Overall, the results of this study show that ARISA is more accurate than T-RFLP analysis on the 16S rRNA gene for estimating the biodiversity of aquatic bacterial assemblages.

The analysis of bacterial ribotype richness is becoming increasingly important from a bio-geographic perspective in order to identify hot spots of microbial biodiversity and to identify the factors influencing their distribution (20, 26). Among all available molecular techniques for investigating prokaryotic diversity (1), genetic fingerprinting techniques allow the estimation of prokaryotic phylotype richness and community composition in a rapid and rather accurate way. Terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) and automated ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis (ARISA) are routinely applied to terrestrial and aquatic samples to estimate the number of bacterial taxa and to investigate spatial and temporal dynamics of bacterial assemblages (26, 41, 47). These techniques are increasingly utilized in ecological studies because they allow processing of a large number of environmental samples (16, 49).

The T-RFLP approach, applied to the 16S rRNA gene, allows semiquantitative estimations of the relative importance of each detected phylotype (3, 24, 28) and in certain cases allows, through the comparison with international databases, identification of the genus or even the species corresponding to the fragment length of each electropherogram (21, 37). On the other hand, ARISA is based on the amplification of the intergenic region between the 16S and 23S rRNA genes in the rRNA operon (known as the ITS1 region), which is characterized by a significant variability in the length and nucleotide sequence among different bacterial genotypes (11, 16). As for the T-RFLP technique, the obtained electropherograms allow quantification of the number, size, and relative abundance of the different members of the bacterial assemblage (48).

Semiautomated fingerprinting techniques (such as ARISA and T-RFLP) have been suggested to be more sensitive than other fingerprinting methods, such as denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis or single-strand conformational polymorphism analysis (28), especially for their abilities to detect also less-abundant taxa within bacterial assemblages (20). It has also been suggested that, while T-RFLP analysis can discriminate prokaryotes to the genus level, ARISA can have a higher resolution, reaching in most cases the species level (20). A recent comparative study carried out in soils suggested that results from ARISA and T-RFLP are closely related (19), but no information is available for aquatic environments on their comparative accuracies and sensitivities in discriminating the different taxa within bacterial assemblages.

In this study, the performance of T-RFLP analysis and ARISA for estimating bacterial diversity and community composition was compared in different environmental matrices. The efficacy of the two techniques to identify bacterial isolates of Pseudomonas spp. from the different environmental samples was also tested in order to investigate their ability to discriminate closely related species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling areas and sample collection.

Water and sediment samples were collected from different marine and freshwater systems (Table 1). Water samples were collected from different sites in order to cover a large spectrum of environmental conditions: (i) coastal seawater samples were collected in the southern part of Sicily (Pachino, Ionian Sea), in an area characterized by the presence of an aquaculture farm (“Pachino water”); (ii) groundwater samples were collected in an aquifer contaminated by hydrocarbons and other contaminants located in central Italy (“groundwater sample”). Sediment samples were collected at five locations: (i) a sandy beach (Palombina) located in the Adriatic Sea (beach sediment sample), (ii) the inner part of Ancona Harbor (Italy; Ancona Harbor sample), (iii) bottom sediments of a coastal fish farm (Pachino sediment sample), and (iv and v) two coastal lagoons (the Lagoon of Lesina and the Lagoon of Goro, Adriatic Sea).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the different sampling areas investigated in this studya

| Location | GPS position | Sample | Acronym | Water depth (m) | Environmental characteristics | Carbon content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palombina (Italy) | 43°37′050N, 13°26′600E | Beach sediment | BS | 1 | Bathing beach | 0.5 ± 0.2 mg g −1 (TOC) |

| Ancona (Italy) | 43°36′.290N, 13°29′.964E | Harbour sediment | AH | 1.5 | High levels of heavy metals (Mn, 420 μg/g; Cr, 20 μg/g) and hydrocarbons (>5 mg/g) | 9.0 ± 1.5 mg g −1 (TOC) |

| Pachino (Italy) | 36°42′.647N, 15°08′.444E | Coastal seawater | PW | 8 | Area subjected to intensive aquaculture | 177.5 ± 20.2 μg liter−1 (POC) |

| Pachino (Italy) | 36°42′.647N, 15°08′.444E | Coastal sediment | PS | 24 | Area subjected to intensive aquaculture | 3.4 ± 1.3 mg g −1 (TOC) |

| Lesina (Italy) | 41°53′.379N, 15°26′.205E | Coastal lagoon sediment | LL | 1.5 | Low-salinity area (15 PSU) | 20.1 ± 2.2 mg g −1 (TOC) |

| Goro (Italy) | 44°49′.536N, 12°16′.800E | Coastal lagoon sediment | LG | 1 | Low-salinity area (14 PSU) | 14.5 ± 2.7 mg g −1 (TOC) |

| Ancona (Italy) | 43°18′.103N, 12°53′.645E | Groundwater | GW | 10 (BSS) | High hydrocarbon contamination (>100 mg/liter of total hydrocarbons) | 60.1 ± 2.8 μg liter−1 (POC) |

BSS, below soil surface; PSU, practical salinity units; TOC, total organic carbon; POC, particulate organic carbon; BS, beach sediment; AH, Ancona Harbor; PW, Pachino water; PS, Pachino sediment; LL, Lagoon of Lesina; LG, Lagoon of Goro; GW, groundwater.

Seawater samples were collected using a Niskin bottle, whereas groundwater samples were obtained using a bailer. One-hundred-ml water samples were prefiltered using heat-sterilized (muffle furnace, 450°C, 2 h) Whatman GF/F filters (diameter, 47 mm; average pore size, 0.7 μm). Although this procedure can result in a partial loss of larger prokaryotic cells and/or cells attached to suspended particles, such a step is necessary to remove small eukaryotic microorganisms, which due to the presence of plastids and mitochondrial DNA might alter the results of the fingerprinting analysis (20). Water samples were subsequently filtered onto sterile Nucleopore polycarbonate filters (diameter, 47 mm; 0.2-μm pore size) under low vacuum (100 mm Hg) and stored at −20°C until DNA extraction and analyses, which were performed within 4 weeks from sampling.

All sediment samples were collected using Plexiglas corers previously treated with 0.1 M HCl to minimize bacterial contamination. About 5 g of sediment from the surficial layer (0 to 1 cm) of each sediment sample was stored in a sterile polypropylene tube (50 ml) at −20°C.

DNA extraction and quantification.

DNA was extracted from water and sediment samples with the UltraClean soil DNA isolation kit (MoBio Laboratories Inc., California). Previous studies revealed that this kit provides estimates of bacterial diversity comparable to those obtained using other direct lysis procedures (27). For DNA extraction from water samples, the kit was adapted as described by Stepanauskas et al. (43). Briefly, to each filter was added 1.8 ml of lysis buffer (0.75 M sucrose, 40 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.3]) and bead solution, 60 μl of S1 solution, and 200 μl of IRS solution provided with the kit. The mixture was then processed according to the manufacturer's instructions. For DNA extraction from sediments, about 1 g of wet sediment was utilized and processed according to the manufacturer's instructions. In all samples, extracted DNA was determined spectrofluorimetrically using SYBR Green I (Molecular Probes) as described by Corinaldesi et al. (10) and quantified using standard solutions of genomic DNA from Escherichia coli. The same amount of extracted DNA was utilized for each T-RFLP and ARISA amplification.

T-RFLP analyses.

For T-RFLP analyses, extracted DNA was amplified using eubacterial universal primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) (both are from reference 23). The forward primer 27F had been labeled at the 5′ end with the fluorescent dye carboxyfluorescein (MWGspa Biotech, Germany). All PCRs were performed in a volume of 50 μl in a thermal cycler (Biometra, Germany) using the MasterTaq kit (Eppendorf AG, Germany), which reduces the effects of PCR-inhibiting contaminants. Thirty PCR cycles were used, consisting of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min, preceded by 3 min of denaturation at 94°C and followed by a final extension of 10 min at 72°C. To check for eventual contamination of the PCR reagents, negative controls containing the PCR mixture but without the DNA template were run during each amplification analysis. Positive controls, containing genomic DNA of Escherichia coli, were also used. PCR products were checked on agarose-Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) gels (1%) containing ethidium bromide for DNA staining and visualization. For each sample, two different PCRs were run and then pooled together to minimize stochastic PCR biases (35, 36). This process was carried out in duplicate, for a total of four different PCRs for each sample. The two resulting PCR combined products were then purified using the Wizard PCR clean-up system (Promega, Wisconsin), resuspended in 50 μl of MilliQ water supplied with the clean-up system, and then quantified spectrofluorimetrically as described above.

About 50 ng of purified 16S rRNA gene amplicons from each of the two duplicate PCRs were digested separately in a 20-μl reaction volume that contained 10 U of the enzyme AluI (Promega) at 37°C for 3 h. This specific restriction enzyme was selected because previous studies demonstrated that it is highly efficient in assessing phylotype richness and bacterial diversity in aquatic assemblages (27, 30, 34). One single restriction enzyme was utilized here for T-RFLP analysis, as several investigations demonstrated that the use of two or more restriction enzymes can produce differences in the community composition (31) but not in term of phylotype richness and diversity estimates based on different indices (13, 15, 19, 44). Restriction digestions were stopped by incubating at 65°C for 20 min, and samples were then kept frozen at −20°C until analysis. Two μl of each digest was mixed with 2 μl of internal size standard (GS1000-ROX; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and with 12 μl in deionized formamide and then denatured at 94°C for 2 min and immediately chilled in ice. Fragments were analyzed in GeneScan mode in an ABI Prism 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) using 47-cm by 50-μm capillaries, POP-4 polymer (Perkin-Elmer), a 40-s injection time, 15-kV injection voltage, 15-kV run voltage, and 60°C capillary temperature. Terminal restriction fragment sizes between 47 and 946 bp were determined using GeneScan analytical software 2.02 (Applied Biosystems). For the analysis and interpretation of T-RFLP profiles, a standardization of the DNA quantity between each of the two duplicate profiles was adopted (14) in order to avoid small differences in the total fluorescence of each profile. Peaks which were less than 1.5 bp apart from a larger peak (“shoulder peaks”) were eliminated. Peaks which were not present in both replicates (“irreproducible peaks”) were considered PCR artifacts and thus removed. According to the approach suggested by Luna et al. (27), the cutoff for the discrimination of each peak from baseline noise was calculated to be 0.16% of the total fluorescence. This value (0.16%) corresponds to the highest number of different peaks which can be discriminated by means of the T-RFLP method with the primer set and the G1000-ROX standard utilized in this study. Then, the maximum number of phylotypes which can be obtained using this technique was obtained by dividing the maximum number of ribotypes which could be observed (1,000 minus 35, or 965) by the minimal distance from two consecutive peaks (1.5 bp). This gives a result of 643 ribotypes which, in case they all equally contributed to the total fluorescence within a single T-RFLP profile, results in a contribution of each ribotype for 0.16% to the total fluorescence (i.e., 1/643 = 0.16%).

ARISA.

For ARISAs, extracted DNA was amplified using universal bacterial primers 16S-1392F (5′-GYACACACCGCCCGT-3′) and 23S-125R (5′-GGGTTBCCCCATTCRG-3′), which amplify the ITS1 region in the rRNA operon plus ca. 282 bases of the 16S and 23S rRNA (20). Primer 23S-125R was fluorescently labeled with the fluorochrome HEX (MWGspa Biotech). PCRs were performed in 50-μl volumes under the same conditions described above for T-RFLP amplifications. Four different reactions were run for each sample and then combined to form two duplicate PCRs, which were subsequently utilized for separate ARISAs. The quality of amplified fragments was checked using electrophoresis on a high-resolution MetaPhor agarose gel (Cambrex). As for T-RFLP amplicons, the two resulting PCR combined products were purified using the Wizard PCR clean-up system (Promega, Madison, Wis.), resuspended in 50 μl of MilliQ water supplied with the clean-up system, and then quantified spectrofluorimetrically as described above.

For each ARISA, about 5 ng of amplicons (corresponding to the same amount of DNA analyzed for T-RFLP analyses) was mixed with 14 μl of internal size standard (GS2500-ROX; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) in deionized formamide, then denatured at 94°C for 2 min, and immediately chilled on ice. Automated detection of ARISA fragments was carried out using the same ABI Prism 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) under the same conditions described above. ARISA fragments in the range of 390 to 1,400 bp were determined using GeneScan analytical software version 2.02 (Applied Biosystems), and the results were analyzed by adopting the same procedure described for T-RFLP, which included standardization of fluorescence among samples, elimination of “shoulder” and nonreplicated peaks, and cutoff criterion. According to the approach suggested by Luna et al. (27), the cutoff for the identification of each genotype was calculated to be 0.11% of the total fluorescence.

T-RFLP and ARISA on Pseudomonas spp. isolates.

Seven Pseudomonas spp. strains were isolated from five different environmental samples using the Pseudomonas agar base (Oxoid) with C-F-C or C-N supplement (Oxoid). This bacterial genus was selected because it represents a ubiquitous and ecologically important component of aquatic assemblages. For water samples, aliquots of each sample were serially diluted and then inoculated into petri plates. For sediment samples, ca. 2 g of fresh material from each sample was added with its own, filter-sterilized water (1:5 [wt/vol]) and vigorously mixed for 1 min in order to detach bacterial cells from sediment particles. Ten-fold serial dilutions were then prepared, and 100-μl aliquots from each dilution were spread in replicates onto petri plates containing the medium. All plates were incubated at 30°C for 24 to 48 h. From the resultant colonies, seven arbitrarily selected colonies were purified by streak plating. Presumptive Pseudomonas identity of the isolates was checked by specific PCR of the 16S rRNA gene with the diagnostic Pseudomonas set of primers (46) and by UV observations of fluorescent pigmentation (42). Isolates were then stored at −80°C in 15% glycerol until DNA extraction.

For DNA extraction, all isolates together with a Pseudomonas reference strain (the pathogenic Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853; Oxoid) were inoculated into tryptic soy broth (Oxoid) and incubated with shaking for 24 or 48 h at 30°C. An aliquot from each culture was then transferred to a 2-ml Eppendorf tube and centrifuged, and the pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of MilliQ sterile water. Cells were lysed at 95°C for 5 min. The test tubes were spun to separate cell material from the supernatant DNA. Two microliters of DNA from each isolate was then used as template for the subsequent T-RFLP and ARISA PCR amplifications.

In order to achieve more specific PCR amplifications in both T-RFLP and ARISA experiments with the Pseudomonas isolates, selective primers for the genus Pseudomonas were utilized. For selective Pseudomonas T-RFLP analyses, 16S rRNA gene amplifications were carried out using the genus-specific primers Ps-for and Ps-rev (46). The forward primer was 5′-tagged with the fluorochrome HEX (MWG). For each isolate, two separate PCRs were run. The amplicons were then electrophoresed on a TBE-agarose gel (1%), purified, and digested as described above. Purified amplicons were digested in duplicate with three different restriction enzymes (AluI, RsaI, and HaeIII; Promega, Wisconsin), and aliquots from each digestion were analyzed for T-RFLP as described above.

For specific ARISAs, the whole ITS1 region plus ca. 750 bp of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified using the Pseudomonas-specific primer set fPs16S/rPs23S (25). PCR conditions were those previously described (25). As for T-RFLP analyses, the forward primer was 5′-labeled with the fluorochrome HEX (MWG). For each isolate, two separate PCRs were run, and the amplicons were electrophoresed on a TBE-agarose gel (1%), purified, and then analyzed as described above.

The phylogenetic identity of the selected isolates was estimated using 16S rRNA gene sequencing, using 1 μl of DNA in a 25-μl PCR volume. PCRs were carried out using the Pseudomonas primer set Ps-for and Ps-rev described above (46). Amplified products were screened by agarose gel electrophoresis and sequenced after cleaning with the ExoSAP-IT kit (USB Corporation). The identity of the isolates was then determined by comparing the obtained sequences with those deposited in the NCBI database using BLAST (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

Bacterial diversity and statistical analyses.

Since T-RFLP analysis is based on the amplification of a highly conserved gene in the species genome, while the ARISA focuses on heterogeneous genome structures, our estimates of bacterial diversity refer to the number of different “phylotypes” (for T-RFLP analyses) and “genotypes” (for ARISAs). Bacterial phylotype/genotype richness was expressed as the total number of peaks within each electropherogram. As described above, only peaks shared by both replicates were considered. According to this conservative procedure, the standard deviation in each sample is nil. For bacterial diversity analyses, the Shannon-Wiener index (H′), which takes into account the number of species present and their relative importance within the assemblage, and the evenness (Pielou index, J), which reflects the relative importance of each taxon within the entire assemblage (12), were calculated. For these calculations, it was assumed that the number of peaks represented the species number (phylotype/genotype richness) and that the peak height represented the relative abundance of each bacterial species (26, 27).

Differences between T-RFLP and ARISA estimates of bacterial diversity were analyzed statistically using the Student test (t test). Differences in bacterial diversity indices were tested using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

To test differences in community composition, the analysis of similarities (ANOSIM, based on Bray-Curtis similarity) was performed using the PRIMER software (7). ANOSIM is a permutation-based statistical test, an analogue of the univariate ANOVA, which tests for differences between groups of (multivariate) samples from different locations and experimental treatments (12, 48).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences of the Pseudomonas sp. pure cultures utilized in this study were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers DQ459011 through DQ459018.

RESULTS

Bacterial diversity.

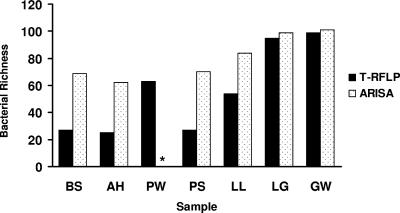

Results of the electropherograms from replicate analyses of T-RFLP and ARISA carried out on the same environmental sample are illustrated in Fig. 1. The comparison of the total bacterial diversity obtained using T-RFLP and ARISA is shown in Fig. 2. Bacterial richness ranged from 27 to 99 (on average, 56 ± 31) with the T-RFLP technique and from 62 to 101 (on average, 81 ± 16) with the ARISA technique. The highest richness was observed in the contaminated aquifer water sample (groundwater sample), while the lowest richness was observed in the polluted Ancona Harbor sediment. Estimates of bacterial richness with T-RFLP and ARISA were significantly correlated (r2 = 0.977; P < 0.001). However, ARISA always yielded a significantly higher richness than T-RFLP (t test; P < 0.01). The only problem was encountered in the analysis of the Pachino seawater sample, in which repeated unsuccessful PCR amplifications were observed with the ARISA technique.

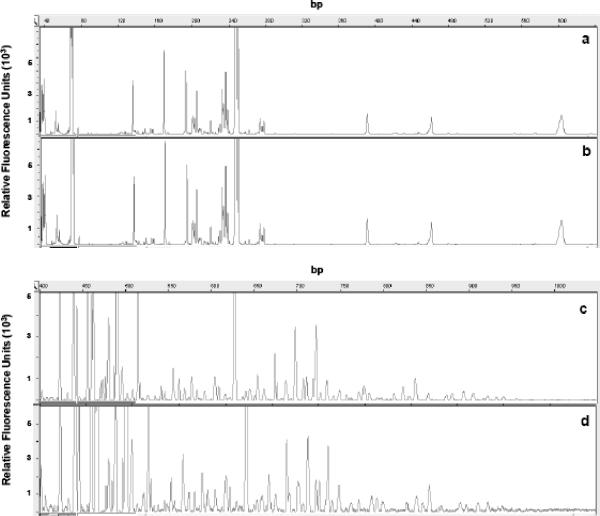

FIG. 1.

Replicated electropherograms from a single aquatic sample. (a and b) Two different T-RFLP analyses of the same sample. (c and d) Two different ARISAs of the same sample. For T-RFLP analysis, the enzyme AluI was used.

FIG. 2.

Bacterial richness estimated using the two fingerprinting techniques (T-RFLP and ARISA). *, not available for ARISA due to repeated unsuccessful PCR amplification.

Bacterial diversity (Shannon-Wiener index, H′) and bacterial evenness (Pielou index, J) are shown in Table 2. The Shannon-Wiener index was significantly higher based on results from ARISA versus T-RFLP (ANOVA; P < 0.01). No differences were observed in the Pielou index (ANOVA; not significant).

TABLE 2.

Bacterial diversity (H′) and bacterial evenness (J) obtained using T-RFLP and ARISAa

| Sample | T-RFLP

|

ARISA

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H′ | J | H′ | J | |

| BS | 2.43 ± 0.018 | 0.74 ± 0.006 | 4.00 ± 0.023 | 0.94 ± 0.005 |

| AH | 2.64 ± 0.005 | 0.82 ± 0.001 | 3.01 ± 0.207 | 0.72 ± 0.050 |

| PW | 3.19 ± 0.004 | 0.77 ± 0.001 | NAb | NA |

| PS | 3.19 ± 0.014 | 0.75 ± 0.004 | 3.47 ± 0.004 | 0.77 ± 0.004 |

| LL | 2.85 ± 0.008 | 0.71 ± 0.000 | 3.67 ± 0.042 | 0.83 ± 0.009 |

| LG | 3.64 ± 0.008 | 0.80 ± 0.003 | 4.26 ± 0.000 | 0.94 ± 0.000 |

| GW | 3.60 ± 0.014 | 0.78 ± 0.000 | 3.61 ± 0.152 | 0.91 ± 0.033 |

| Avg | 3.08 ± 0.17 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 3.67 ± 0.16 | 0.85 ± 0.04 |

| Min | 2.43 ± 0.018 | 0.71 ± 0.000 | 3.01 ± 0.207 | 0.72 ± 0.050 |

| Max | 3.64 ± 0.008 | 0.95 ± 0.004 | 4.26 ± 0.000 | 0.94 ± 0.005 |

H′ is the Shannon-Wiener index, and J was calculated with the Pielou index. Values are means±standard errors. For explanation of sample site acronyms, see footnote a of Table 1.

NA, not applicable.

Bacterial community composition.

The total number of taxa detected with T-RFLP and ARISA was 144 and 200, respectively. Thus, overall ARISA allowed identification of ca. 40% more bacterial taxa than T-RFLP. The use of different cutoff criteria (i.e., 50 fluorescence units) resulted in similar results (data not shown).

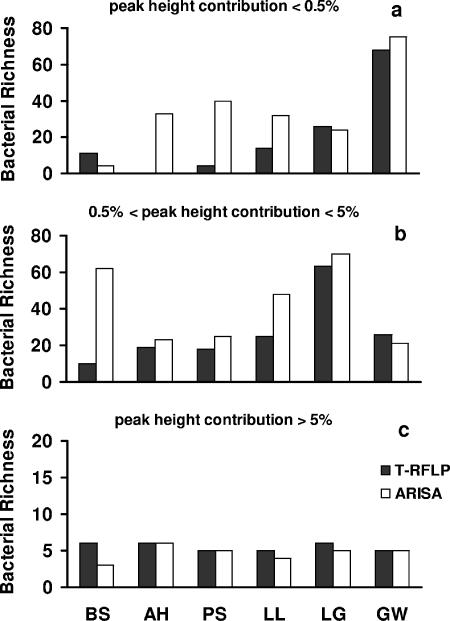

To test whether the two techniques had similar efficacies in detecting both less abundant and dominant taxa within bacterial assemblages, we compared the effects of three cutoff levels within each T-RFLP and ARISA profile (<0.5%, >0.5% and <5%, and >5% of total fluorescence, both for T-RFLP and ARISA), which represent the levels of the contributions of a single taxon to the total fluorescence in each electropherogram (Fig. 3). T-RFLP and ARISA provided similar results when we used the highest cutoff (i.e., >5% of total fluorescence), but T-RFLP had a lower resolution for the identification of less abundant taxa (i.e., accounting for less than <5% of the total fluorescence). With the lowest cutoff level (i.e., <0.5% of total fluorescence), on average 35 taxa (range, 4 to 75) were identified using ARISA, whereas only 21 (range, 0 to 68) were identified with T-RFLP. For the intermediate cutoff level (between 0.5% and 5%), the average values were 42 (range, 21 to 70) and 27 (range, 10 to 63) taxa for ARISA and T-RFLP, respectively. The number of taxa detected within these two categories was significantly higher with ARISA than with T-RFLP (ANOVA; P < 0.05).

FIG. 3.

Numbers of bacterial taxa were estimated using the different cutoff levels applied to ARISA and T-RFLP profiles. (a) Number of taxa contributing <0.5% to the total fluorescence; (b) number of taxa contributing 0.5 to 5% of the total fluorescence; (c) number of taxa contributing >5% of the total fluorescence.

In order to test whether the two techniques have the same effectiveness in evaluating differences in bacterial community composition among samples from different environments, an ANOSIM analysis (analysis of similarity) was carried out. The analysis allows statistical testing if differences exist between groups of community samples. The ANOSIM analysis revealed that both T-RFLP and ARISA allowed distinction of all the different samples with equal statistical significance (for both techniques, R = 1).

T-RFLP and ARISA on Pseudomonas spp. isolates.

In order to experimentally evaluate whether ARISA and T-RFLP have different efficiencies in distinguishing among aquatic isolates, these techniques also were applied to Pseudomonas spp. isolates. The affiliation of these isolates was investigated using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Isolate 1 was closely related to Pseudomonas sp. strain KBOS 04 1558 (98% identity), Pseudomonas sp. ARDRA PS1′ (98%), Pseudomonas sp. A1Y dBTEX1-5 (98%), Pseudomonas veronii strains A1XB2-5 and A1XdBTEX (98%), Pseudomonas marginalis strain NZCX (98%), Pseudomonas sp. strain ST5 (98%), Pseudomonas sp. strain TB4-4-I (98%), Pseudomonas sp. strain ps11-13 (98%), and Pseudomonas sp. strain PH-05 (98%). Isolates 2 and 3 were close to Pseudomonas aurantiaca VKM B-816T (97%) and to Pseudomonas sp. strain MFY63 (97%). Isolate 4's closest relative was Pseudomonas sp. strain MFY152 (98%). Isolate 5 was very close to Pseudomonas sp. strain SN1 (99%), Pseudomonas sp. strain SB1 (99%), Pseudomonas sp. strain 5.1 (99%), Pseudomonas sp. strain K6-4L-018 (99%), Pseudomonas sp. strain K6-28L-033 (99%), Pseudomonas chloritidismutans (99%), and Pseudomonas stutzeri strains DSM 50227, AN11, and AN10 (99%). Finally, isolates 6 and 7 were all closely related to Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains (all at 99%).

T-RFLP and ARISA carried out on the eight Pseudomonas isolates are shown in Table 3, and an example of electropherograms obtained from one isolate using all of the different restriction enzymes and the two fingerprinting techniques is shown in Fig. 4.

TABLE 3.

Results of T-RFLP analysis and ARISA for Pseudomonas sp. isolates

| Isolate no. | Source of isolationa | T-RFLP

|

ARISA

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restriction enzyme | T-RF length (bp) | No. of peaks | Amplicon length (bp) | ITS1 lengthb (bp) | ||

| P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) | AluI | 356 | 1 | 1,289 | 470 | |

| RsaI | 363 | |||||

| HaeIII | 602 | |||||

| 1 | Aquifer (GW) | AluI | 554 | 2 | 1,178 | 359 |

| RsaI | 599 | 1,434 | 615 | |||

| HaeIII | 603 | |||||

| 2 | Aquifer (GW) | AluI | 357 | 1 | 1,295 | 476 |

| RsaI | 164 | |||||

| HaeIII | 601 | |||||

| 3 | Seawater (PW) | AluI | 357 | 1 | 1,273 | 454 |

| RsaI | 163 | |||||

| HaeIII | 600 | |||||

| 4 | Sediment (LL) | AluI | 357 | 1 | 1,327 | 508 |

| RsaI | 599 | |||||

| HaeIII | 603 | |||||

| 5 | Sediment (LL) | AluI | 356 | 1 | 1,355 | 536 |

| RsaI | 598 | |||||

| HaeIII | 603 | |||||

| 6 | Sediment (BS) | AluI | 357 | 1 | 1,178 | 359 |

| RsaI | 364 | |||||

| HaeIII | 604 | |||||

| 7 | Sediment (AH) | AluI | 357 | 1 | 1,266 | 447 |

| RsaI | 363 | |||||

| HaeIII | 603 | |||||

For explanation of source acronyms, see footnote a of Table 1.

Length in base pairs of the ITS1 region, calculated by subtracting the length of the amplified 16S and 23S regions.

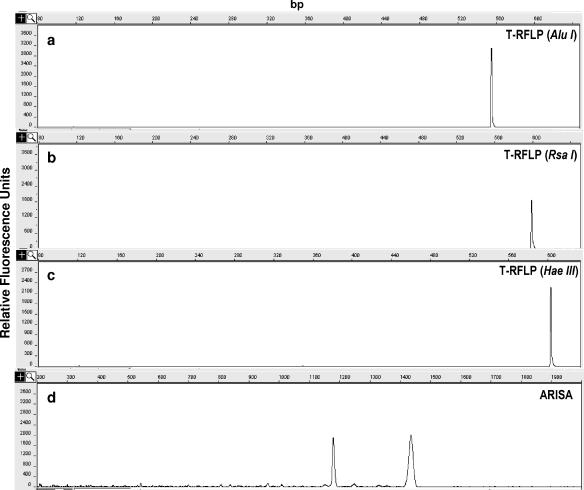

FIG. 4.

Examples of electropherograms obtained from a Pseudomonas sp. isolate (isolate 1) using T-RFLP and ARISA. (a to c) T-RFLP electropherograms resulting from the use of the restriction enzymes AluI (a), RsaI (b), and HaeIII (c). (d) ARISA electropherogram.

The T-RFLP analysis always produced one single peak for each isolate and each restriction digestion. For all the isolates analyzed with T-RFLP (assuming a resolution in size of ±1 bp), four different restriction patterns were observed: (i) 554, 599, and 603 bp for isolate 1 using AluI, RsaI, and HaeIII, respectively; (ii) 357, 164, and 601 bp for isolates 2 and 3; (iii) 357, 599, and 603 for isolates 4 and 5; and (iv) 357, 364, and 604 bp for isolates 6 and 7 and the reference Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain.

The ARISA generally produced one single peak per bacterial isolate, with the only exception being isolate 1, which produced two different peaks (Table 3). ITS1 length ranged from 359 to 615 bp (average length, 469 bp). Assuming that accuracy in sizing of these fragments, which are longer than those analyzed by T-RFLP, is ±10 bp (16), ARISA grouped the Pseudomonas spp. isolates into six different groups: 359 and 615 bp (for isolate 1), 470 to 476 bp (for isolate 2 and the reference P. aeruginosa strain), 447 to 454 bp (for isolates 3 and 7), 508 bp (for isolate 4), 536 bp (for isolate 5), and 359 bp (for isolate 6).

DISCUSSION

The ARISA technique is based on the analysis of intergenic 16S-23S internally transcribed spacer sequences (ITS1) within the rRNA operon, whereas T-RFLP targets the 16S rRNA gene. Previous investigations pointed out that the ITS1 region, having a noncoding function, can be more variable in the nucleotide sequence than the 16S rRNA gene (2, 9, 17, 32).

The sequences of 16S rRNA genes have been shown to be very similar among different bacterial species and, thus, are ineffective in distinguishing among closely related genomic groups (17). This applies also to the marine environment, as recent investigations carried out in the Sargasso Sea demonstrated the presence of extensive genomic heterogeneity among lineages with similar or identical 16S rRNA gene sequences (45). Conversely, the analysis of bacterial ITS1 sequences appears to enable identification to the species or even strain level (18, 33, 40).

Additional advantages of ARISA, when compared to T-RFLP, are due to its fast procedure and the low costs (19). This is due to the fact that ARISA does not require the enzymatic digestion of the amplicons, as required for T-RFLP, so that purified PCR products can be directly analyzed using capillary electrophoresis. On the other hand, available information on bacterial ITS1 sequences in the GenBank database is still limited, whereas T-RFLP analysis allows a comparison with a large database (Ribosomal Database Project), which can provide useful information for identification of bacterial taxa to the level of genera or species (3, 6, 21, 29, 38, 39).

This study was designed to evaluate the most appropriate technique for estimating bacterial diversity in different aquatic systems. The results indicated that, in accordance with previous studies (19, 41), that bacterial diversity was higher when analyzed using ARISA compared with the T-RFLP technique. However, a recent study conducted in soils (19) provided evidence that two fingerprinting techniques (T-RFLP and RISA) were statistically equivalent in distinguishing bacterial communities in soil samples subjected to different treatments. Conversely, our results indicate that ARISA yields a significantly higher bacterial diversity (H′) and evenness (J) than T-RFLP. Since J refers to the distribution of bacterial abundance among different taxa, our results suggest that ARISA gives a picture of a more homogenous bacterial community composition than the T-RFLP technique. From these results, it can be inferred that ARISA has a higher resolution to detect taxa that account for less than 5% of total amplified product. Different results between aquatic and terrestrial environments can be also explained by the presence of different bacterial species, but our findings indicate that this result is consistent in all aquatic matrices (seawater, freshwater, and marine and lagoon sediments). In this study, diversity indices were calculated using peak height, and we assumed that they represented the relative abundance of each phylotype/genotype. However, although such a procedure has been largely utilized for the calculation of diversity indices (references 20, 26, and 27 and citations therein), it must be used with extreme caution (13, 14), since capillary electrophoretic analyses can be biased by interference of shorter fragments with larger fragments, and we cannot exclude that the use of different restriction enzymes could lead to different estimates of bacterial diversity and evenness. Therefore, values of diversity calculated using peak height may be not as accurate in the description of the actual in situ diversity. In the present study, it is impossible to determine if any interference occurred. Nonetheless, our data allow a comparison with all available information on bacterial diversity that has been estimated using the same procedure in different aquatic systems.

Another possible source of bias could be due to PCR amplification of mixed DNA templates (35, 36). However, the robustness of ARISA and T-RFLP in providing consistent profiles (in both peak number and relative height) is increasingly documented (4, 16). This fact, together with all precautions adopted for minimizing PCR artifacts (see details in Materials and Methods), allows our hypothesis that possible PCR biases did not significantly alter our results.

Pseudomonas spp. isolates from our environmental samples were used to test the efficiencies of T-RFLP and ARISA in characterizing bacterial isolates (3, 30, 38). Results reported here confirm that ARISA was more effective than T-RFLP in discriminating among aquatic Pseudomonas phylotypes, as the T-RFLP provided identical results for two isolates (for isolates 2 and 3) for which ARISA provided different ITS1 lengths. ARISA, indeed, in organisms displaying 99% 16 rRNA gene similarity (e.g., isolates 6 and 7 and the P. aeruginosa reference strain), allowed detection of different ITS lengths, suggesting a higher level of resolution. This result is consistent with recent findings on bacterioplankton diversity based on ARISA and clone libraries (4, 5).

The advantages of the analysis of the ITS1 region, compared with the analysis of the 16S rRNA gene, have also been reported for other bacterial genera, such as Porphyromonas and Fusobacterium (8, 9) and, together with our results, further support the conclusion that ARISA has a higher taxonomic resolution for the analysis of bacterial diversity in aquatic samples. These findings might have important ecological implications, as different ITS lengths might correspond to phenotypes having different ecological roles (reference 5 and references therein). Therefore, the analysis of bacterial diversity based on ARISA can provide additional information in ecological studies.

The results obtained in the present study using ARISA and T-RFLP were significantly and positively correlated, but ARISA had a higher resolution than T-RFLP at both low and high levels of diversity in all samples analyzed. However, such differences were more evident (60 to 160% higher) in samples characterized by a low number of taxa.

The SIMPER analysis, which estimates the similarity among a group of samples (10), revealed that, on average, the dissimilarity among investigated samples was ca. 77% with T-RFLP and 75% with ARISA. Thus, completely different bacterial taxa characterized the samples collected in the different aquatic systems, and this may have important implications for the estimation of the global bacterial diversity in aquatic systems.

Within the bacterial genome, the rRNA operon might be present in several copies (from 1 to 15), depending on the species (22). These operons may have 16S-23S intergenic regions of different lengths and sequences. In this case, a single species will produce more peaks in the ARISA electropherogram, thus leading to an overestimation of the richness of bacterial taxa. Our results with Pseudomonas spp. isolates indicated that only in one case over eight isolates (i.e., 12.5% of the samples analyzed) did the ARISA electropherogram produce two peaks. This result is consistent with the relatively low frequency of multiple peaks (ca. 13%) calculated for all ITS1 sequences deposited in the GenBank (16). Nonetheless, even if this fraction were excluded from our estimates of genotype richness, results from the ARISA technique would remain significantly higher than those based on T-RFLP. In this regard, recent studies on marine bacteria have reported a low intragenomic heterogeneity among multiple rRNA operons from single organisms (4, 5), suggesting that biases in the ITS analysis deriving from multiple operons may be negligible.

Overall, our results indicate that both ARISA and T-RFLP are useful fingerprinting techniques for assessing bacterial species richness and diversity in aquatic samples. However, the results of this study indicate that ARISA is more accurate than T-RFLP analysis on 16S rRNA for estimating the biodiversity of aquatic bacterial assemblages.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Manini (CNR-ISMAR, Ancona) for her precious help during sample collection.

This research was financially supported by ISPESL (contract no. B96/DIPIA/03, “Messa a punto di tecniche biomolecolari per la caratterizzazione delle comunità microbiche responsabili dei processi biodegradativi e per la determinazione rapida degli isolati di Pseudomonas sp.”), by FIRB 2001 (contract no. RBAU012KXA009 MIUR), by COFIN2003 (NITIDA contract no. 2003051023_001, MIUR), and by the EU Project “MEDVEG” (FP5; EU contract no. Q5RS-2001-02456).

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann, R., B. M. Fuchs, and S. Behrens. 2001. The identification of microorganisms by fluorescence in situ hybridisation. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 12:231-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berridge, B. R., J. D. Fuller, J. De Azavedo, D. E. Low, H. Bercovier, and P. F. Frelier. 1998. Development of specific nested oligonucleotide PCR primers for the Streptococcus iniae 16S-23S ribosomal DNA intergenic spacer. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2778-2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackwood, C. B., T. Marsh, S. H. Kim, and E. A. Paul. 2003. Terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism data analysis for quantitative comparison of microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:926-932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, M. V., M. S. Schwalbach, I. Hewson, and J. A. Fuhrman. 2005. Coupling 16S-ITS rDNA clone libraries and automated ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis to show marine microbial diversity: development and application to a time series. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1466-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, M. V., and J. A. Fuhrman. 2005. Marine bacterial microdiversity as revealed by internal transcribed spacer analysis. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 41:15-23. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen, J. E., J. A. Stencil, and K. D. Reed. 2003. Rapid identification of bacteria from positive blood cultures by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism profile analysis of the 16S rRNA gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3790-3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke, K. R. 1993. Nonparametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Austr. J. Ecol. 18:117-143. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conrads, G., M. C. Claros, D. M. Citron, K. L. Tyrrell, V. Merriam, and E. J. C. Goldstein. 2002. 16S-23S rDNA internal transcribed spacer sequences for analysis of the phylogenetic relationships among species of the genus Fusobacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:493-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conrads, G., D. M. Citron, K. L. Tyrrell, H. P. Horz, and E. J. Goldstein. 2005. 16S-23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer sequences for analysis of the phylogenetic relationships among species of the genus Porphyromonas. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55:607-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corinaldesi, C., R. Danovaro, and A. Dell'Anno. 2005. Simultaneous recovery of extracellular and intracellular DNA suitable for molecular studies from marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:46-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daffonchio, D., A. Cherif, L. Brusetti, A. Rizzi, D. Mora, A. Boudabous, and S. Borin. 2003. Nature of polymorphisms in 16S-23S rRNA gene intergenic transcribed spacer fingerprinting of Bacillus and related genera. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5128-5137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danovaro, R., A. Dell'Anno, and A. Pusceddu. 2004. Biodiversity response to climate change in a warm deep sea. Ecol. Lett. 7:821-828. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunbar, J., L. O. Ticknor, and C. R. Kuske. 2000. Assessment of microbial diversity in four southwestern United States soils by 16S rRNA gene terminal restriction fragment analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2943-2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunbar, J., L. O. Ticknor, and C. R. Kuske. 2001. Phylogenetic specificity and reproducibility and new method for analysis of terminal restriction fragment profiles of 16S rRNA genes from bacterial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:190-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edlund, A., T. Soule, S. Sjoling, and J. K. Jansson. 2006. Microbial community structure in polluted Baltic Sea sediments. Environ. Microbiol. 8:223-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher, M. M., and E. W. Triplett. 1999. Automated approach for ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis of microbial diversity and its application to freshwater bacterial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4630-4636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guasp, C., E. R. Moore, J. Lalucat, and A. Bennasar. 2000. Utility of internally transcribed 16S-23S rDNA spacer regions for the definition of Pseudomonas stutzeri genomovars and other Pseudomonas species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:1629-1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurtler, V., and V. A. Stanisich. 1996. New approaches to typing and identification of bacteria using the 16S-23S rDNA spacer region. Microbiology 142:3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartmann, M., B. Frey, R. Kolliker, and F. Widmer. 2005. Semi-automated genetic analyses of soil microbial communities: comparison of T-RFLP and RISA based on descriptive and discriminative statistical approaches. J. Microbiol. Methods 61:349-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hewson, I., and J. A. Fuhrman. 2004. Richness and diversity of bacterioplankton species along an estuarine gradient in Moreton Bay, Australia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3425-3433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kent, A. D., D. J. Smith, B. J. Benson, and E. W. Triplett. 2003. Web-based phylogenetic assignment tool for analysis of terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism profiles of microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6768-6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klappenbach, J. A., P. R. Saxman, J. R. Cole, and T. M. Schmidt. 2001. RRNDB: the ribosomal RNA operon copy number database. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:181-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lane, D. J. 1991. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing, p. 115-175. In E. Stackebrandt and M. Goodfellow (ed.), Nucleic acid technology in bacterial systematics. John Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 24.Liu, W. T., T. L. Marsh, H. Cheng, and L. J. Forney. 1997. Characterization of microbial diversity by determining terminal restriction fragment length polymorphisms of genes encoding 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4516-4522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Locatelli, L., S. Tarnawski, J. Hamelin, P. Rossi, M. Aragno, and N. Fromin. 2002. Specific PCR amplification for the genus Pseudomonas targeting the 3′ half of 16S rDNA and the whole 16S-23S rDNA spacer. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 25:220-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luna, G. M., A. Dell'Anno, L. Giuliano, and R. Danovaro. 2004. Bacterial diversity in deep Mediterranean sediments: relationship with the active bacterial fraction and substrate availability. Environ. Microbiol. 6:745-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luna, G. M., A. Dell'Anno, and R. Danovaro. 2006. DNA extraction procedure: a critical issue for bacterial diversity assessment in marine sediments. Environ. Microbiol. 8:308-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marsh, T. L. 1999. Terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP): an emerging method for characterizing diversity among homologous populations of amplicons. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:323-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nilsson, W. B., and M. S. Strom. 2002. Detection and identification of bacterial pathogens of fish in kidney tissue using terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis of 16S rRNA genes. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 48:175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osborn, A. M., E. R. B. Moore, and K. Timmis. 2000. An evaluation of terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis for the study of microbial community structure and dynamics. Environ. Microbiol. 2:39-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osborne, C. A., G. N. Rees, Y. Bernstein, and P. H. Janssen. 2006. New threshold and confidence estimates for terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of complex bacterial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1270-1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez-Luz, S., M. A. Yanez, and V. Catalan. 2004. Identification of waterborne bacteria by the analysis of 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer region. J. Appl. Microbiol. 97:191-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perez-Luz, S., F. Rodriguez-Valera, R. Lan, and P. R. Reeves. 1998. Variation of the ribosomal operon 16S-23S gene spacer region in representatives of Salmonella enterica subspecies. J. Bacteriol. 180:2144-2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pett-Ridge, J., and M. K. Firestone. 2005. Redox fluctuations structures microbial communities in a wet tropical soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:6998-7007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polz, M. F., and C. M. Cavanaugh. 1998. Bias in template-to-product ratios in multitemplate PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3724-3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qiu, X., L. Wu, H. Huang, P. E. McDonel, A. V. Palumbo, J. M. Tiedje, and J. Zhou. 2001. Evaluation of PCR-generated chimeras, mutations, and heteroduplexes with 16S rRNA gene-based cloning. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:880-887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ricke, P., S. Kolb, and G. Braker. 2005. Application of a newly developed ARB software-integrated tool for in silico terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis reveals the dominance of a novel pmoA cluster in a forest soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1671-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogers, G. B., C. A. Hart, J. R. Mason, M. Hughes, M. J. Walshaw, and K. D. Bruce. 2003. Bacterial diversity in cases of lung infection in cystic fibrosis patients: 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) length heterogeneity PCR and 16S rDNA terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism profiling. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3548-3558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogers, G. B., M. P. Carroll, D. J. Serisier, P. M. Hockey, G. Jones, and K. D. Bruce. 2004. Characterization of bacterial community diversity in cystic fibrosis lung infections by use of 16s ribosomal DNA terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism profiling. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5176-5183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schloter, M., M. Lebuhn, T. Heulin, and A. Hartmann. 2000. Ecology and evolution of bacterial microdiversity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24:647-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwalbach, M. S., I. Hewson, and J. A. Fuhrman. 2004. Viral effects on bacterial community composition in marine planktonic microcosms. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 34:117-127. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stach, J. E. M., S. Bathe, J. P. Clapp, and R. G. Burns. 2001. PCR-SSCP comparison of 16S rDNA sequence diversity in soil DNA obtained using different isolation and purification methods. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 36:139-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stepanauskas, R., M. A. Moran, B. A. Bergamaschi, and J. T. Hollibaugh. 2003. Covariance of bacterioplankton composition and environmental variables in a temperate delta system. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 31:85-98. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Urakawa, H., T. Yoshida, M. Nishimura, and K. Ohwada. 2000. Characterization of depth-related population variation in microbial communities of a coastal marine sediment using 16S rDNA-based approaches and quinone profiling. Environ. Microbiol. 2:542-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Venter, J. C., K. Remington, J. F. Heidelberg, A. L. Halpern, D. Rusch, J. A. Eisen, D. Wu, I. Paulsen, K. E. Nelson, W. Nelson, D. E. Fouts, S. Levy, A. H. Knap, M. W. Lomas, K. Nealson, O. White, J. Peterson, J. Hoffman, R. Parsons, H. Baden-Tillson, C. Pfannkoch, Y. H. Rogers, and H. O. Smith. 2004. Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea. Science 304:66-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Widmer, F., R. J. Seidler, P. M. Gillevet, L. S. Watrud, and G. D. Di Giovanni. 1998. A highly selective PCR protocol for detecting 16S rRNA genes of the genus Pseudomonas (sensu stricto) in environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2545-2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winter, C., A. Smit, G. J. Herndl, and M. G. Weinbauer. 2004. Impact of virioplankton on archaeal and bacterial community richness as assessed in seawater batch cultures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:804-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yannarell, A. C., and E. W. Triplett. 2004. Within- and between-lake variability in the composition of bacterioplankton communities: investigations using multiple spatial scales. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:214-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yannarell, A. C., and E. W. Triplett. 2005. Geographic and environmental sources of variation in lake bacterial community composition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:227-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]