Abstract

The conformational deformability of nucleic acids can influence their function and recognition by proteins. A class of DNA binding proteins including the TATA box binding protein binds to the DNA minor groove, resulting in an opening of the minor groove and DNA bending toward the major groove. Explicit solvent molecular dynamics simulations in combination with the umbrella sampling approach have been performed to investigate the molecular mechanism of DNA minor groove deformations and the indirect energetic contribution to protein binding. As a reaction coordinate, the distance between backbone segments on opposite strands was used. The resulting deformed structures showed close agreement with experimental DNA structures in complex with minor groove-binding proteins. The calculated free energy of minor groove deformation was ∼4–6 kcal mol−1 in the case of a central TATATA sequence. A smaller equilibrium minor groove width and more restricted minor groove mobility was found for the central AAATTT and also a significantly (∼2 times) larger free energy change for opening the minor groove. The helical parameter analysis of trajectories indicates that an easier partial unstacking of a central TA versus AT basepair step is a likely reason for the larger groove flexibility of the central TATATA case.

INTRODUCTION

The conformational flexibility of DNA is central to its many biological functions. Specific binding by proteins is not only determined by specific interactions between DNA and proteins but also by the global structure and deformability of the DNA helix (1–6). Conformational deformability of nucleic acids can influence their function and the recognition by proteins. Several DNA binding proteins bind to the minor groove of DNA and result in a significant deformation of the minor groove from the standard B-DNA geometry (7). Among these are prokaryotic DNA repressors, e.g., the purR (purine repressor) DNA complexes (8), the eukaryotic transcription factor TBP (TATA-box binding protein) (9–12), the high mobility group (HMG) proteins LEF-1 (lymphoid enhancer-binding factor) (13), HMG-D (14), testis-determining factor SYR (15), NHP6A (16), and DNA repair enzymes (17,18). All these minor groove-binding proteins induce a qualitatively similar global conformational change in the target DNA that leads to an opening and greater accessibility of the minor groove and bending of the DNA toward the major groove. In eukaryotes, DNA is packed in nucleosomes (wrapped around a histone octamer core) and adopts a strongly curved structure (19). The packing of DNA also leads to a periodic pattern of minor and major groove opening/closing deformations. The DNA flexibility and its sequence dependence can influence the position of the histone octamer binding along the DNA (nucleosome positioning) (20,21). In addition to several DNA binding proteins, association of synthetic minor groove-binding ligands (drugs) to DNA can involve minor groove deformations of the target DNA (22). These may also contribute to binding affinity although the drug-induced conformational changes in DNA are smaller than in the case of minor groove-binding proteins.

The binding of minor groove-binding ligands and proteins must provide sufficient energy to enforce groove opening at the target sequence. Hence, the binding affinity to the DNA target is not only influenced by the direct protein-DNA interactions but also indirectly by the sequence dependence of the global deformability of the DNA. For example, in the case of the TBP changes of the TATA recognition sequence, both affect binding affinity and the degree of DNA bending of the TBP-DNA complex (23,24). However, the recognition of TATA box sequences by TBP is also strongly affected by flanking sequences (25,26), and any DNA sequence change can affect both direct interactions with the protein (direct readout) and intrinsic structure/flexibility of the DNA (indirect readout). For TBP (27) and the HMG-domain proteins, it has been shown that prebending of the target DNA either by disulfide cross-linking (28,29) or intrastrand cross-linking using the anticancer drug cisplatin can enhance protein-DNA binding affinity (30–35). The disulfide cross-link reduces the distance between two nucleotides in the major groove and leads to a prebending of ∼30° and opening of the DNA minor groove (28). The cisplatin drug causes a 1,2-intrastrand cross-link at d(GpG) steps in DNA and produces a stable kink at the damage site (31,33). The degree of DNA-binding enhancement due to DNA modification and prebending depends on the DNA sequence and the type of minor groove-binding protein. For HMG-D (HMGB protein of Drosophila melongaster) the binding to disulfide cross-linked and prebend DNA was enhanced by a factor of ∼5 (29). For another testis-specific mouse HMG-domain, a binding enhancement of between 20 and 230 to cisplatin-modified DNA has been reported for the full protein versus isolated HMG-domain A, respectively (34). For the TATA box binding protein, a 175-fold increase in binding affinity to a TATA box with flanking cisplatin cross-links compared to unmodified target DNA was found (27). These results indicate that the effect of DNA predeformation on DNA-binding affinity can be quite dramatic. The large variety of affinity enhancements is probably due to the fact that the conformational change introduced by the DNA modification may show varying degrees of overlap with the required DNA deformation to adopt an ideal interface for protein association, complicating the distinction of contributions due to direct versus indirect readout.

Using continuum solvent calculations, it has been proposed that the low dielectric environment of an approaching protein may increase the phosphate repulsion on the minor groove side of the DNA and promote binding (36). However, partial phosphate neutralization by positively charged residues on the protein might also reduce the energy barrier to open the minor groove of DNA as found by Lebrun et al. (37) and Lebrun and Lavery (38) in energy minimization studies (see below). Large-scale deformations that relate also to protein binding have been systematically studied by Boutonnet et al. (39), Kosikov et al. (40), and Zakrzewska (41). However, these simulation studies neglect explicit solvent that might be critical to estimate the energetics of DNA conformational changes. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in explicit water have been used extensively to study the flexibility of DNA and its fine structure (42–44, reviewed in Cheatham (45)) and also to investigate the flexibility of the TATA box containing DNA sequences (46,47). In a recent effort, the DNA fine structure of all possible tetranucleotides has been investigated by unrestrained MD simulations (48,49). However, on the timescale of these simulations, complete spontaneous transitions to a conformation as found in complex with minor groove-binding proteins are rarely observed in unrestrained MD simulations.

To investigate the minor groove deformation mechanism and the energetic contribution to the recognition process, explicit solvent MD simulations in combination with the umbrella sampling approach have been performed in this study. As a reaction coordinate, the distance between sugar-phosphate backbone atoms of two nucleotides on opposite strands was used. It has been shown by Boutonnet et al. (39), Lebrun et al. (37), and Lebrun and Lavery (38) that a similar distance restraint employed during energy minimization can induce a DNA structural transition similar to the deformation seen in several DNA duplexes complexed to minor groove-binding proteins. The purpose of this study is to perform the DNA minor groove opening under more realistic conditions including explicit solvent molecules and counterions and to extract the free energy change associated with the transition. Simulations have been performed on two DNA duplexes with the same nucleotide contents but different central sequences (TATATA versus AAATTT). The results give an estimate on the free energy contribution of DNA minor groove deformation to recognition and indicate a significant sequence dependence of the calculated free energy of minor groove deformation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Two 12-bp B-DNA molecules with different central sequences (six basepairs) but the same flanking sequences and same nucleotide content ((central AAATTT case: 5′-dGCGAAATTTCGC)2 and central TATATA case: (5′-dGCGTATATACGC)2) were used. Standard B-DNA start structures were generated using the nucgen program of the Amber8 package (50). Each system was neutralized by adding 22 K+ counterions and solvated with ∼6500 TIP3P water molecules (51) in a rectangular box and energy minimized using the sander module of Amber8. During MD, each DNA was initially harmonically restrained (25 kcal mol−1 Å−2) to the energy minimized start coordinates; and the system was heated up to 300 K in steps of 100 K followed by gradual removal of the positional restraints over a period of 0.2 ns followed by 1-ns unrestrained equilibration at 300 K. During the MD simulations, the long-range electrostatic interactions were treated with the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method using a real space cutoff distance of rcuttoff = 9 Å. The Rattle algorithm (52) was used to constrain bond vibrations involving hydrogen atoms, which allows a time step of 2 fs. To induce the desired minor groove opening during the simulation, a distance restraint between centers of mass of two groups of atoms on opposite strands was used. Test calculations indicated that single reference atoms to define a distance restraining coordinate can lead to local deformations in the nucleic acid backbone conformation. The atoms that formed the two groups consisted of P, O5′, C5′, C4′, C3′, O3′ (of nucleotide 8), and P, O5′ (of nucleotide 9) on both strands. The distance vector between the centers of these two groups points approximately in the direction of the helical DNA axis (see Fig. 1). A quadratic umbrella potential with respect to the distance reaction coordinate was applied (small force constant: 0.5 kcal mol−1Å−2) and the reference distance was changed from 9 to 20 Å in steps of 1 Å. The potentials of mean force (PMF) along the reaction coordinate was calculated from the recorded distance data set (recorded every 10 MD steps) using the weighted histogram analysis (WHAM) method (53,54). For each reference distance 0.2-ns equilibration simulation followed 3-ns data gathering were performed. The deformed structures at dref = 19 Å were used to start backward simulations (2 ns per reference distance). Helical and backbone parameters of the structures obtained as trajectories (recorded every 2 ps) were analyzed using the program Curves 5.0 (55,56).

FIGURE 1.

Snapshots of deformed DNA molecules (central TATATA case) during MD simulations at three different interstrand target distances. The view is along the central part of the minor groove (van der Waals representation using a heavy atom color code excluding hydrogen atoms). The groups on both strands that determine the center-of-mass distances are encircled. The atoms that formed the two groups consisted of P, O5′, C5′, C4′, C3′, O3′ (of nucleotide 8), and P, O5′ (of nucleotide 9) on both strands (see Materials and Methods). dref = 10.0 Å represents approximately the DNA equilibrium minor groove width, whereas dref = 18.0 Å corresponds to a conformation close to the DNA in complex with minor groove-binding proteins.

RESULTS

Free energy change associated with minor groove deformation

MD umbrella sampling simulations were used to study the minor groove deformability of two A/T-rich sequences flanked by G/C-rich caps on both sides. Both strands of each oligonucleotide had the same sequence, and both DNAs had the same nucleotide content. It is advantageous for a better control of the simulations to use self-complementary sequences (same sequence on both strands that should give on average the same results for both strands during the simulations). The first system contained the sequence TATATA at the center (d(GCGTATATACGC)2). Sequences similar to the TATATA sequence are frequently found within TATA-box transcription factor binding boxes (23), whereas the second sequence (d(GCGAAATTTCGC)2) is atypical. Although no experimental data on TBP binding to the AAATTT sequence are available, studies on the TAAAAA or TAAATA motif indicate strongly reduced binding affinity (>100-fold reduction in complex stability, 23).

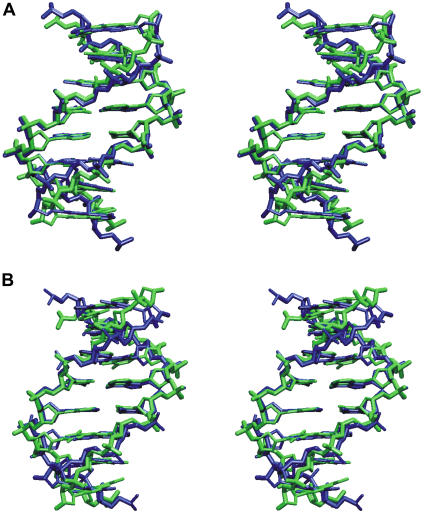

The DNA minor groove of both DNA oligonucleotides was opened during MD simulations using a soft quadratic restraining potential on the distance between centers of mass of two backbone segments on both strands (see Materials and Methods section). The reference distance (dref) was changed in steps of 1 Å starting at dref = 9 Å (Fig. 1). At dref = 17–18 Å, the deformed duplexes adopted a structure very close to DNA structures observed in complex of minor groove-binding proteins and their respective target DNA molecule (Fig. 2). For example, superposition of the average structure with central TATATA (dref = 17 Å) on the target sequence of the purR-recognition motif (8) resulted in a nucleic acid backbone root mean-square deviation (RMSD) of ∼1.8 Å (Fig. 2 A). Similarly, superposition of the TATA box segment from the complex with TBP (12) onto the central TATATA element at dref = 18 Å gave an RMSD of 1.7 Å (Fig. 2 B).

FIGURE 2.

(A) Superposition (nucleic acid backbone) of experimental purR-DNA (green, central 12 bp, pdb2pub, (8)) onto deformed DNA with central TATATA sequence (blue, dref = 18 Å). (B) Superposition of a snapshot of the deformed TATATA structure (blue, dref = 18 Å) onto experimental TATA box structure from a complex with the TBP protein (pdb1TGH, nucleotides 101–106/119–124 superimposed on central 6 basepairs of the TATATA structure). For clarity, only heavy atoms are shown.

Using the WHAM method (53,54), the simulations allowed calculation of the free energy change required to deform a central AAATTT sequence compared to a central TATATA sequence (Fig. 3). Comparison of free energy curves for different simulation windows and for the backward simulations indicates a good convergence of the calculated PMF profiles (Fig. 3). A significant difference of the free energy change required to open the minor groove to reach a state receptive for binding a minor groove-binding protein was found. For dref = 17 Å the calculated free energy change is ∼8 kcal mol−1 (AAATTT sequence) compared to ∼4 kcal mol−1 in the case of the central TATATA sequence (Fig. 3). Under the assumption that the induced deformation corresponds exactly to the structural difference between bound and unbound forms of the DNA, this predeformation would increase the affinity for a hypothetical protein by a factor of ∼800 (=exp(−ΔG/RT), R: gas constant, T: temperature) for the central TATATA case. In the case of the AAATTT sequence, the direct protein-DNA interactions need to provide an additional ∼4 kcal mol−1 to allow minor groove opening. This additional free energy difference translates to an ∼800 times smaller binding constant and points to a significant “indirect” readout contribution to specificity.

FIGURE 3.

Calculated potential of mean force for the minor groove deformation of the DNA molecule with central AAATTT (bold lines) and TATATA (thin lines) sequence. The minor groove width is controlled by the reference distances (dref) between backbone segments on opposite strands (see Materials and Methods). Red, green, and black curves correspond to PMF obtained after 1-, 2-, and 3-ns data gathering time per dref. The dashed curves indicate the PMF for the backward simulations starting from dref = 19 Å.

Interestingly, the calculated optimal minor groove width is smaller for the AAATTT case than in the case of the TATATA sequence. A broader range of minor groove widths appears accessible in the latter case with only small changes in free energy (Fig. 3). However, at reference distances smaller than the distance corresponding to the optimal minor groove width, the onset of a steep free energy increase occurs already at larger distances in the TATATA case compared to the AAATTT sequence. The ability to adopt a narrower minor groove correlates with the ability to adopt larger (negative) propeller twist angles, which for sterical reasons are more easily possible in the case of the AAATTT sequence. The adenine bases in the TATATA motif show significant interstrand cross stacking (Fig. 4). Significant negative propeller twist leads to sterical clashes of interstrand cross-stacked bases. For the other motif, the thymidine bases on opposite strands at the center are smaller and show only a little cross-stacking, allowing for more extensive propeller twisting and in turn for a more narrow minor groove (Fig. 4). The observed smaller equilibrium minor groove width of the AAATTT case is consistent with the experimental observation of relatively narrow minor grooves of DNA duplexes with central AATT or AAATTT sequences compared to other sequences (57). The free energy minimum for the AAATTT case is between dref = 9–10 Å, whereas in the case of the TATATA sequence the conformation of lowest free energy appears at dref ∼ 12 Å. A superposition of the average AAATTT structure obtained at dref = 10 Å onto a crystal structure containing the same central segment (Protein Data Bank (pdb)1S2R, 57) resulted in an RMSD of <1 Å (heavy atoms of the central six basepairs, Fig. 5 A) and a close agreement of the size of the minor groove. In the case of the central TATATA, a superposition on a crystal structure with central TATA sequence (pdb1D29, 58) also resulted in close agreement (RMSD < 1.5 Å for the central four basepairs, Fig. 5 B). The result indicates that the sequence-dependent groove properties are quite well reproduced by the free energy minima of the two cases.

FIGURE 4.

View into the minor groove (stick model) of the central AAATTT structure (A) and central TATATA structure (B), respectively, at small reference distance (dref = 9 Å). The double arrow indicates the free space available in the case of the AAATTT structure that allows easy propeller twisting at the central basepair step to further reduce the minor groove size. Contrarily, the cross-stacking arrangement of the two adenine bases at the central basepair step in the TATATA structure (double arrow in B) largely prevents propeller twisting as a possibility to further reduce the minor groove width.

FIGURE 5.

(A) Superposition (stereo view) of the average structure for the central AAATTT sequence at dref = 10 Å (green) onto the central AAATTT motif in the x-ray structure of the B-DNA: d(CGCAAATTTGCG)2 (blue, pdb1S2R; (57)). (B) Superposition of the average structure for the central TATATA sequence at dref = 12 Å (green) onto the central TATA motif in the x-ray structure of the B-DNA decamer d(CGATATATCG)2 (blue, pdb1D29; (58)). The view is into the minor groove and for clarity only the eight central basepairs (heavy atoms) are shown.

Helical structure of the deformed DNA

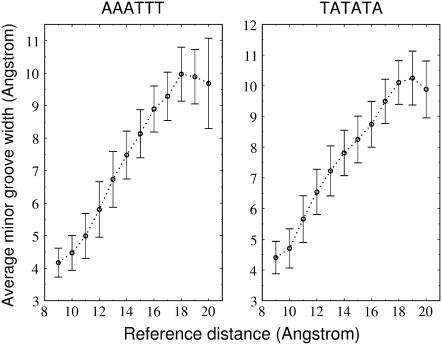

The minor groove width calculated using the program Curves 5.0 (55,56) correlates with the reference distance used as reaction coordinate in these simulations (Fig. 6) up to dref = 18 Å. Beyond this reference distance, the minor groove width (as calculated in Curves based on several phosphate-phosphate distances along a DNA segment) started to decrease due to changes in the nucleic backbone structure (see last paragraph of the Results section). In addition to minor groove opening, the binding of minor groove-binding proteins causes significant bending of the target DNA. Consistent with the experimental observation the average bend angle of deformed DNA duplexes increased during the simulations with the reference distance up to dref = 18 Å and reached ∼45° (Fig. 7). Beyond this it decreased due to backbone rearrangements (see last paragraph of the Results section). In crystal structures of DNA in complex with minor groove-binding proteins, bend angles of 30°–130° have been reported (7–15) that exceed (in part) what was observed in these simulations. However, during the simulations DNA bend angle fluctuations of up to 55°–60° were observed (Fig. 7). It is important to note that the recognition elements of minor groove-binding proteins usually extend beyond a central element such that not only the central element but also other flanking DNA regions may contribute to the larger bend angles observed in several x-ray crystal complex structures compared to these simulations.

FIGURE 6.

Average minor groove width obtained during data gathering time with the program Curves (55,56) versus the reaction coordinate used to induce minor groove deformation (error bars indicate standard deviations).

FIGURE 7.

Average global bending (calculated using Curves) obtained during data gathering time versus reaction coordinate (interstrand separation: dref; error bars indicate standard deviations).

The average helical parameter's roll and twist showed a significant correlation with respect to the reaction coordinate (Fig. 8 A). In the case of the AAATTT sequence, the central roll angle showed a relatively small increase up to dref = 18 Å followed by a more dramatic increase at larger reference distances. In contrast, in the case of the central TATATA motif, larger central roll angles were observed already at smaller values of the reaction coordinate. The larger central roll leads to a more pronounced central kinking and partial unstacking in the case of the TATATA sequence (illustrated in Fig. 8 B). For both DNA molecules, a decrease of the average twist angle of the central element was observed with ∼34° at dref = 9 Å down to ∼27° for dref = 18 Å and ∼23° for largest dref = 20 Å (Fig. 8 C). Such a decrease of the twist has also been observed in experimental DNA structures in complex with minor groove-binding ligands (7). The error bars on the helical and global variables reflect the highly dynamic nature of the DNA even during these restrained simulations.

FIGURE 8.

(A) Central helical basepair roll angle versus minor groove opening reaction coordinate (reference distance, dref). (B) Central basepair steps using a stick representation. For clarity, only heavy atoms of average structures at dref = 17 Å are shown. The distance between the centers of the central basepairs is marked (double arrow). (C) Average central twist (average over five central steps) versus minor groove opening reaction coordinate (dref).

Nucleic acid backbone structure

At small reference distances, the dihedral angle δ that largely determines the desoxy-ribose sugar pucker state (correlates with the pucker phase angle) is mainly distributed around an average value of ∼140°, which is characteristic for B-DNA (C2′-endo sugar pucker; for both sequences, Fig. 9). With increasing dref, the distribution changes with transitions to δ = 85° that are more characteristic of A-form duplex structures (C3′-endo sugar pucker). Such local transitions to an A-form-type structure is consistent with the reduced twist (see above) and also with experimental DNA structures in complex with minor groove-binding proteins (7–15). Transitions to A-form have also been found in energy minimization studies along a distance constraint used to open the DNA minor groove by Lebrun et al. (37) and Lebrun and Lavery (38). However, in these MD simulations, no complete transition of the central segment to A-form geometry was observed (Fig. 9). Interestingly, at the largest reference distances, the DNA again adopted a desoxy-ribose pucker characteristic of B-DNA (Fig. 9 A, see below). The DNA backbone structure is not only influenced by the desoxy-ribose pucker conformation but also by other backbone dihedral torsion angles. The most common transitions in DNA that still retain a near B-form structure are due to coupled changes in the dihedral angles α and γ (α/γ flips or crank shift motions) as well as changes in the dihedral angles ɛ and ζ (BI-BII transitions). The distribution of the dihedral angles γ and ɛ at different reference distances were used to monitor α/γ flips and BI-BII states, respectively (Fig. 9, B and C). A γ around 60° (+gauche) is highly correlated with α in the −gauche regime and represents regular B-DNA. A transition of γ toward the trans-regime (mostly coupled to a change in α from −gauche to trans) indicates an α/γ flip. Correspondingly, an ɛ in the trans regime represents regular B-DNA (BI), and a transition to −gauche indicates a BII state. At dref < 18 Å the distribution for the central part of the duplexes indicates only very few transitions to α/γ flips or BII states. However, at dref > 18 Å, a more significant proportion of the nucleotide backbone undergoes α/γ flips or adopts BII states (Fig. 9, B and C). The increased number of α/γ flips can be due to the increased sterical stress at large reference distances but also due to deficiencies of the molecular mechanics force field.

FIGURE 9.

Distribution of nucleic acid backbone dihedral angles during data gathering time at dref = 10 Å (black line), 15 Å (dashed line), 18 Å (dotted dashed line), and 20 Å (dotted line).

The significant changes in the nucleic acid backbone structure at the largest dref are also visible in the overall geometry of the nucleic acid structures (Fig. 10). A smooth regular nucleic acid backbone is seen in the average structures from the simulations up to dref = 18 Å. However, at dref = 19 or 20 Å, the backbone changes to a zigzag-shaped geometry near the central region, which still allows for a large distance between centers of mass of the reference nucleotides. The minor groove width of this type of structure as calculated by Curves and the average bending angle are significantly smaller compared to the structure at dref = 18 Å (Figs. 6 and 7). The structural change is accompanied by local α/γ flips or BII states found at the largest dref (Fig. 9), and the sugar puckers of these structures redistribute to adopt mainly C2′-endo conformations. The central basepairs at dref = 19 or 20 Å start to show a positive basepair inclination relative to the helical axis (Fig. 10). Structures with strong negative basepair inclination have been proposed to occur upon DNA stretching, termed S-DNA (59,60). However, this structure clearly differs from the proposed S-DNA since basepair inclination in S-DNA is in the opposite direction, resulting in a strongly enhanced major groove accessibility and reduced minor groove width (59). It should also be noted that the S-DNA conformation is experimentally not well characterized, allowing no quantitative comparison to these results. This structure is more similar to intermediate structures obtained during DNA stretching at the 3′-ends (61). The rise at the central steps increases from ∼3.3–3.4 Å in structures with dref < 18 Å to ∼3.4–3.8 at dref = 19–20 Å. The resulting nonoptimal stacking of the basepairs is also likely to allow easier intercalation of ligands or protein sidechains.

FIGURE 10.

Stereo view of the average DNA structure (central AAATTT sequence) at dref = 18 Å (A) and dref = 20 Å (B). The view is into the minor groove and only heavy atoms are shown (stick representation). The structures are available from the author upon request.

DISCUSSION

The binding of minor groove-binding proteins can induce large changes in the DNA minor groove and is expected to be strongly influenced by the DNA flexibility. From the binding affinities and the structure of isolated DNA versus deformed structure in complex with proteins alone, it is difficult to separate contributions due to direct protein-DNA contacts versus indirect contributions due to the sequence-dependence of the DNA deformability. For computational efficiency, previous theoretical studies on global DNA deformability have often neglected explicit solvent and ions often employing a distance-dependent dielectric constant to account for electrostatic interactions (36–41). In this study, a distance restraint between groups of atoms on the two DNA strands was applied during explicit solvent umbrella sampling MD simulations similar to a restraint coordinate used by Lebrun et al. (37) and Lebrun and Lavery (38) to induce minor groove opening during energy minimization. Similar to these adiabatic mapping energy minimization studies (37,38), a transition to conformations close to the DNA structure seen in DNA in complex with minor groove-binding proteins was observed. Also, the changes in helical structure concerning the behavior of central roll and reduction of twist upon minor groove deformation agrees well with the experimental results on minor groove-binding protein DNA complexes (7–15). The increase of the central roll leads to a partial unstacking at the central basepair step; and the onset of the central kink starts at smaller minor groove deformations in the case of the TATATA simulation. In contrast to energy minimization, the umbrella sampling simulation includes explicit solvent and counterions and the effect of DNA conformational fluctuations and allows a more realistic estimate of the penalty for DNA deformation. Indeed, the energy minimization studies resulted in a considerably higher energy penalty for minor groove opening of ∼20–30 kcal mol−1 for a TATA box-type sequence (37,38) compared to these free energy simulations. Depending on the degree of minor groove opening, these free energy simulations resulted in a free energy penalty of ∼4–5 kcal mol−1 in the case of the central TATATA sequence (∼8–10 kcal mol−1 in the case of the AAATTT sequence). This result can be compared to protein binding to predeformed DNA due to disulfide or cisplatin cross-linking (27–35). The difference in protein binding to linear versus predeformed DNA should reflect the contribution of DNA deformability. However, the observed binding affinity changes due to DNA cross-linking vary considerably. Depending on the type of protein binding partner and cross-link, binding affinity increases of ∼5–200 have been reported (27,29,34). Presumably, this large variation is due to imperfect agreement of the predeformed versus bound conformations of the DNA in the complex. The penalty obtained for the TATATA case translates to a deformation contribution factor of ∼800. The predicted deformation penalty in the case of the AAATTT sequence is even larger. However, the calculations agree qualitatively with the fact that the latter sequence type is a poor target sequence for TBP binding. It has been found for the TBP/TATA box case that the target sequence can affect both the binding affinity and the induced DNA bending angle (23). These simulations indicate that it is easier to deform and bend the TATATA target sequence toward the major groove compared to the AAATTT case. It is possible that a lower affinity binding to the DNA target sequence creates only an imperfect fit between DNA and protein that requires a less deformed DNA structure (hence less energy is also spent to induce DNA deformation). Again it is important to keep in mind that the induced deformation during these simulations is in good but not in perfect agreement with the experimentally observed deformations, and the free energy change can only be considered as an estimate of the deformability contribution to binding affinity and specificity. The greater tendency for unstacking at the central TA step (TATATA case) compared to the AT step (in the AAATTT sequence) agrees with experimental results on the stacking tendency of dinucleotide steps (62,63). Among the 10 dinucleotide steps, TA steps have the smallest stacking free energy. However, in protein-DNA complexes the central partial unstacking in the minor groove is often supported by intercalation of a hydrophobic (sometimes aromatic) side chain. This interaction might also help minor groove opening in a sequence-specific manner; that is, the side chain preferentially interacts with a certain nucleobase and is not accounted for in this simulation study.

The calculated free energy curves showed an approximately quadratic behavior for small deviations from the equilibrium geometry. Interestingly, a much narrower free energy curve centered around a smaller optimal minor groove width was obtained for the AAATTT case compared to the TATATA motif. This agrees well with the experimental observation that AAATTT sequences in crystal structures adopt a narrow minor groove. The average DNA conformations that corresponded to the free energy minima along the minor groove deformation reaction coordinate showed very good agreement with the experimental structures with central AAATTT or TATA motifs, respectively. Beyond a certain deformation, however, the free energy increased approximately linearly with increasing deformation with a slight tendency to level off at large deformations. This onset of the significant free energy increase occurred at a larger minor groove opening distance in the case of the central TATATA compared to the AAATTT sequence and appears to be the main reason for the larger free energy penalty found for the AAATTT case. It has also been found in unrestrained MD simulations that DNA fragments with a central TATA box motif do have an intrinsic tendency toward a more open minor groove (42,46,47). It is likely that the broader range of minor groove widths available in the case of the TATATA sequence may also help during the protein (e.g., TBP) binding process to initiate the binding reaction. After an initial association, further opening of the minor groove is probably a stepwise process where formation of protein-DNA interactions provides energy to further deform the DNA target sequence (induced fit).

At small reference distances below the distance that corresponds to an optimal minor groove width, the free energy increases sharply. Interestingly, in this case the onset of the free energy increase occurs already at larger distances for the TATATA sequence compared to the AAATTT case. Negative propeller twisting of the central basepairs corresponds to one possible mechanism to reduce the minor groove width without significantly deforming the nucleic acid backbone structure. Negative propeller twist is sterically compatible with a central AT but less so with a central TA step (cross stacking between adenine bases at the center, Fig. 4), which offers a structural explanation for the “delayed” onset of a free energy rise (at smaller dref) in the case of the central AAATTT sequence.

Interestingly, at large restraining reference distances (dref > 18 Å), the DNA structure switched from a form close to the structure in complex with minor groove-binding proteins toward a structure with positively inclined basepairs and changes in the nucleic acid backbone structure (Fig. 10). The stretched structure is (locally) reminiscent of intermediate structures obtained during molecular modeling calculations on DNA deformation (40) and DNA stretching using the distance between 3′-ends of DNA as a reaction coordinate (61). It is interesting to note that DNA structures with locally deformed backbone geometry have also been observed in complexes of DNA with minor groove-binding proteins (e.g., the LEF-1 protein-DNA complex, 13). The local changes in backbone structure and deviation from optimal stacking geometry may help protein side chains to intercalate between DNA basepairs.

CONCLUSIONS

The umbrella sampling simulations allowed the estimation of the indirect readout contribution of the DNA minor groove deformation to the binding of minor groove-binding proteins. This is an important structural DNA deformation observed in a large number of protein-DNA complexes that goes beyond equilibrium fluctuations observed in unrestrained simulations. The application to two model systems of different sequences but the same nucleotide contents also allowed obtaining an impression on the sequence dependence of the indirect readout contribution to protein-DNA recognition. An extension to other DNA sequences or to chemically modified DNA structures is possible to more comprehensively understand the role of DNA deformability during protein binding and for understanding recognition and repair of chemically modified or damaged DNA.

Acknowledgments

I thank J. Curuksu, Drs. A Barthel, C. Prevost, N. Riemann and D. Roccatano for helpful discussions.

This work was performed using the computational resources of the CLAMV (Computer Laboratories for Animation, Modeling and Visualization) at IUB and supercomputer resources of the EMSL (Environmental Molecular Science Laboratories) at the PNNL (Pacific Northwest National Laboratories; grant gc11-2002).

References

- 1.Hagerman, P. J. 1990. Flexibility of DNA. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 59:755–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El Hassan, M. A., and C. R. Calladine. 1995. The assessment of the geometry of dinucleotide steps in double-helical DNA: a new local calculation scheme. J. Mol. Biol. 251:648–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olson, W. K., A. A. Gorin, X.-J. Lu, L. M. Hock, and V. B. Zhurkin. 1998. DNA sequence dependent deformability deduced from protein-DNA crystal complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:11163–11168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Packer, M. J., M. P. Dauncey, and C. A. Hunter. 2000. Sequence-dependent DNA structure: tetranucleotide conformational maps. J. Mol. Biol. 295:85–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhodes, D., J. W. Schwabe, L. Chapman, and L. Fairall. 1996. Towards an understanding of protein-DNA recognition. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 351:501–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deremble, C., and R. Lavery. 2005. Macromolecular recognition. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15:171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bewley, C. A., A. M. Gronenborn, and G. M. Clore. 1998. Minor groove-binding architectural proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 27:105–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schumacher, M. A., K. Y. Choi, H. Zalkin, and R. G. Brennan. 1994. Crystal structure of LacI member, PurR, bound to DNA: minor groove binding by alpha helices. Science. 266:763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim, J. L., D. B. Nikolov, and S. K. Burley. 1993. Co-crystal structure of TBP recognizing the minor groove of a TATA element. Nature. 365:520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim, Y., J. H. Geiger, S. Hahn, and P. B. Sigler. 1993. Crystal structure of a yeast TBP/TATA-box complex. Nature. 365:512–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim, J. L., and S. K. Burley. 1994. 1.9 Å resolution refined structure of TBP recognizing the minor groove of TATAAAAG. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1:638–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikolov, D. B., H. Chen, E. D. Halay, A. Hoffman, R. G. Roeder, and S. K. Burley. 1996. Crystal structure of a human TATA box-binding protein/TATA element complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:4862–4867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Love, J. J., X. Li, D. A. Case, K. Giese, R. Grosschedl, and P. E. Wright. 1995. Structural basis for DNA bending by the architectural transcription factor LEF-1. Nature. 376:791–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy, F. V., R. M. Sweet, and M. E. Churchill. 1999. The structure of a chromosomal high mobility group protein-DNA complex reveals sequence-neutral mechanisms important for non-specific DNA recognition. EMBO J. 18:6610–6618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy, E. C., V. B. Zhurkin, J. M. Louis, G. Cornilescu, and G. M. Glore. 2001. Structural basis for SRY-dependent 46-X,Y sex reversal: modulation of DNA bending by natural occurring point mutation. J. Mol. Biol. 312:481–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masse, J. E., B. Wong, Y.-M. Yen, F. H.-T. Allain, R. Johnson, and J. Feigon. 2002. The S. cerevisiae architectural HMGB protein NHP6A complexed with DNA: DNA and protein conformational changes upon binding. J. Mol. Biol. 323:263–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Obmolova, G., C. Ban, P. Hsieh, and W. Yang. 2000. Crystal structures of mismatch repair protein MutS and its complex with a substrate DNA. Nature. 407:703–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banerjee, A., W. Yang, M. Karplus, and G. L. Verdine. 2005. Structure of a repair enzyme interrogating undamaged DNA elucidates recognition of damaged DNA. Nature. 434:612–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richmond, T. J., and C. A. Davey. 2003. The structure of DNA in the nucleosome core. Nature. 423:145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felsenfeld, G., and M. Groudine. 2003. Controlling the double helix. Nature. 421:448–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, G., and J. Widom. 2004. Nucleosomes facilitate their own invasion. Nat. Struct. Biol. 11:763–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dervan, P. B., and B. S. Edelson. 2003. Recognition of the DNA minor groove by pyrrole-imidazole polyamides. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13:284–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Starr, B. D., B. C. Hoopes, and D. K. Hawley. 1995. DNA bending is an important component of site-specific recognition by the TATA binding protein. J. Mol. Biol. 250:434–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoopes, B. C., J. F. LeBlanc, and D. K. Hawley. 1998. Contributions of the TATA box sequence to rate limiting steps in transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II. J. Mol. Biol. 277:1015–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bareket-Samish, A., I. Cohen, and T. E. Haran. 2000. Signals for TBP/TATA box recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 299:965–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faiger, H., M. Ivanchenko, I. Cohen, and T. E. Haran. 2006. TBP flanking sequences: asymmetry of binding, long-range effects and consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:104–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen, S. M., E. R. Jamieson, and S. J. Lippard. 2000. Enhanced binding of the TATA-binding protein to TATA boxes containing flanking cisplatin 1,2-cross-links. Biochemistry. 39:8259–8265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfe, S. A., A. E. Ferentz, V. Grantcharova, M. E. Churchill, and G. L. Verdine. 1995. Modifying the helical structure of DNA by design: recruitment of an architecture-specific protein to an enforced DNA bend. Chem. Biol. 2:213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klass, J., F. V. Murphy, S. Fouts, M. Serenil, A. Changela, J. Siple, and M. E. Churchill. 2003. The role of intercalating residues in chromosomal high-mobility-group protein DNA binding, bending and specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:2852–2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohndorf, U.-M., J. P. Whitehead, N. L. Raju, and S. J. Lippard. 1997. Binding of tsHMG, a mouse testis-specific HMG-domain protein, to cisplatin-DNA adducts. Biochemistry. 36:14807–14815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunham, S. U., and S. J. Lippard. 1997. DNA sequence context and protein composition modulate HMG-domain protein interaction of cisplatin-modified DNA. Biochemistry. 36:11428–11436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohndorf, U.-M., M. A. Rould, Q. He, C. O. Pabo, and S. J. Lippard. 1999. Basis for the recognition of cisplatin-modified DNA by high-mobility-group proteins. Nature. 399:708–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen, S. M., Y. Mikata, Q. He, and S. J. Lippard. 2000. HMG-domain protein recognition of cisplatin 1,2-intrastrand d(GpC) cross-links in purine-rich sequence contexts. Biochemistry. 39:11771–11776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He, Q., U.-M. Ohndorf, and S. J. Lippard. 2000. Intercalating residues determine the mode of HMG1 domains A and B binding to cisplatin-modified DNA. Biochemistry. 39:14426–14435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malina, J., M. Vojtiskova, V. Brabec, C. I. Diakos, and T. W. Hambley. DNA adducts of the enantiomers of the Pt(II) complexes of the ahaz ligand (ahaz=3-aminohexahydroazepine) and recognition of these adducts by HMG domain proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 332:1034–1041. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Elcock, A., and J. A. McCammon. 1996. The low dielectric interior of proteins is sufficient to cause major structural changes in DNA on association. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118:3787–3788. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lebrun, A., Z. Shakked, and R. Lavery. 1997. Local DNA stretching mimics the distortion caused by the TATA box-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:2993–2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lebrun, A., and R. Lavery. 1999. Modeling DNA deformations induced by minor groove binding proteins. Biopolymers. 49:341–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boutonnet, N., X. Hui, and K. Zakrzewska. 1993. Looking into the grooves of DNA. Biopolymers. 33:479–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kosikov, K. M., A. A. Gorin, V. B. Zhurkin, and W. K. Olson. 1999. DNA stretching and compression: large-scale simulations of double helical structures. J. Mol. Biol. 289:1301–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zakrzewska, K. 2003. DNA deformation energetics and protein binding. Biopolymers. 73:414–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lankas, F., T. E. Cheatham 3rd, N. Spackova, P. Hobza, J. Langowski, and J. Sponer. 2002. Critical effect of the N2 amino group on structure, dynamics, and elasticity of DNA poly-purine tracts. Biophys. J. 82:2592–2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lankas, F., J. Sponer, J. Langowski, and T. E. Cheatham. 2003. DNA deformability at the base pair level. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:4124–4125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lankas, F., J. Sponer, J. Langowski, and T. E. Cheatham. 2004. DNA basepair step deformability inferred from molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 85:2872–2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheatham, T. E. 2004. Simulation and modeling of nucleic acid structure, dynamics and interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14:360–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flatters, D., M. Young, D. L. Beveridge, and R. Lavery. 1997. Conformational properties of the TATA-box binding sequence of DNA. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 14:757–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flatters, D., and R. Lavery. 1998. Sequence-dependent dynamics of TATA-box binding sites. Biophys. J. 75:372–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beveridge, D. L., G. Barreiro, K. S. Byun, D. A. Case, T. E. Cheatham 3rd, S. B. Dixit, E. Giudice, F. Lankas, R. Lavery, J. H. Maddocks, R. Osman, E. Seibert, H. Sklenar, G. Stoll, K. M. Thayer, P. Varnai, and M. A. Young. 2004. Molecular dynamics simulations of the 136 unique tetranucleotide sequences of DNA oligonucleotides. I. Research design and results on d(CpG) steps. Biophys. J. 87:3799–3813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dixit, S. B., D. L. Beveridge, D. A. Case, T. E. Cheatham 3rd, E. Giudice, F. Lankas, R. Lavery, J. H. Maddocks, R. Osman, H. Sklenar, K. M. Thayer, and P. Varnai. 2005. Molecular dynamics simulations of the 136 unique tetranucleotide sequences of DNA oligonucleotides. II: Sequence context effects on the dynamical structures of the 10 unique dinucleotide steps. Biophys. J. 89:3721–3740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Case, D. A., D. A. Pearlman, J. W. Caldwell, T. E. Cheatham III, W. S. Ross, C. L. Simmerling, T. A. Darden, K. M. Merz, R. V. Stanton, A. L. Cheng, J. J. Vincent, M. Crowley, V. Tsui, R. J. Radmer, Y. Duan, J. Pitera, I. Massova, G. L. Seibel, U. C. Singh, P. K. Weiner, and P. A. Kollman. 2003. Amber 8. University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

- 51.Jorgensen, W., J. Chandrasekhar, J. Madura, R. Impey, and M. Klein. 1983. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyamoto, S., and P. A. Kollman. 1992. Settle: an analytical version of the SHAKE and RATTLE algorithm for rigid water models. J. Comput. Chem. 13:952–962. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar, S., D. Bouzida, R. H. Swendsen, P. A. Kollman, and J. M. Rosenberg. 1992. The weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method. J. Comput. Chem. 13:1011–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grossfield, A. 2003. http://dasher.wustl.edu/alan

- 55.Lavery, R., and H. Sklenar. 1988. The definition of generalized helicoidal parameters and of axis curvature for irregular nucleic acids. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 6:63–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lavery, R., and H. Sklenar. 1988. Defining the structure of irregular nucleic acids: conventions and principles. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 6:655–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Woods, K. K., T. Maehigashi, S. B. Howerton, S. S. Sines, S. Tannenbaum, and L. D. Williams. 2004. High-resolution structure of an extended A-tract [d(CGCAAATTTGCG)]2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:15330–15337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yuan, H., J. Quintiana, and R. E. Dickerson. 1992. Alternative structures for alternating poly(dA-dT) tracts: the structure of the B-DNA decamer CGATATATCG. Biochemistry. 31:8009–8016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cluzel, P., A. Lebrun, C. Heller, R. Lavery, J.-L. Viovy, D. Chatenay, and F. Caron. 1996. DNA: an extensible molecule. Science. 271:792–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith, S. B., Y. Cui, and C. Bustamante. 1996. Overstretching of B-DNA: the leastic response of individual double-stranded and single-stranded DNA molecules. Science. 271:795–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lebrun, A., and R. Lavery. 1996. Modelling extreme stretching of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:2260–2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sponer, J., P. Jureka, and P. Hobza. 2004. Accurate interaction energies of hydrogen-bonded nucleic acid base pairs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:10142–10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yakovchuk, P., E. Protozanova, and M. D. Frank-Kamenetskii. 2006. Base-stacking and base-pairing contributions into thermal stability of the DNA double helix. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:564–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]