Abstract

By RT-PCR, we isolated a partial cDNA clone for the chick Semaphorin7A (Sema7A) gene. We further analyzed its expression patterns and compared them with those of the Sema3D gene, in chick embryonic development. Sema3D and Sema7A appeared to be expressed in distinct cell populations. In mesoderm-derived structures, Sema7A expression was detected in the newly formed somites, whereas Sema3D expression was found in the notochord. In ectoderm-derived tissues, Sema3D is expressed broadly in the surface ectoderm, lens and nasal placodes. Sema3D is also expressed in the developing nervous system including diencephalon, dorsal neural tube, optical and otic vesicles. In the limb bud, Sema3D expression was found throughout the ectoderm excluding the apical ectoderm ridge (AER), where Sema7A is concentrated. Although both genes appeared to be expressed in the migrating neural crest cells, Sema3D expression is limited to neural crest cells migrating out of the midbrain/hindbrain regions, while Sema7A expression is widespread in both cranial and trunk neural crest cells.

Keywords: expression patterns, ectoderm, limb bud, chick, embryogenesis

INTRODUCTION

Semaphorins comprise one of the largest families of axon guidance cues, sharing a conserved SEMA domain containing approximately 500 amino acids (Raper, 2000; Pasterkamp and Kolodkin, 2003). The central feature of the SEMA domain is a seven-blade β-propeller fold similar to the β-propeller repeats of integrin α subunits. Based on sequence similarity and structural features, semaphorin proteins are classified into eight subclasses: Class 1 and 2 semaphorins are found in invertebrate species and class V semaphorins are found in the genomes of certain DNA viruses. Class 3–7 semaphorins are expressed in vertebrates: secreted proteins in class 3, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins in class 7, and transmembrane proteins in classes 4 to 6. Two receptor families, plexins and neuropilins, have been characterized to mediate semaphorin functions. Except for class 3 semaphorins, which require neuropillins as co-receptors, other semaphorins bind to plexins and activate downstream signaling pathways.

Many axon guidance factors have recently been shown to play a role in the development of non-neural tissues, including Netrin, Slit, Ephrin, and Semaphorin families (Hinck, 2004). It has been suggested that Netrin and the DCC-related receptor neogenin help stabilize cell layers during organogenesis of the mammary gland (Srinivasan et al., 2003). Netrin also interacts with integrin to mediate migration of pancreatic epithelial cells at early stages of development (Yebra et al., 2003). Slit proteins are expressed in a wide range of tissues outside the central nervous system, including the urogenital system, limb and tooth primordia (Piper and Little, 2003). Slit/Robo signaling has been shown to be important for kidney development (Grieshammer et al., 2004). Slit also regulates migration of myoblast cells, mesodermal cells, and leukocyte chemotaxis in Drosophila and vertebrates (Wong et al., 2002). It has been shown that ephrins and Eph receptors are involved in confining migrating cells to appropriate pathways and preventing intermixing of the cells at the boundaries, such as segmental interfaces in the hindbrain and somites (Durbin et al., 1998; Xu et al., 1999; Poliakov et al., 2004), in angiogenesis (Wang et al., 1998; Gerety et al., 1999), and during neural crest cell migration (Krull et al., 1997; Wang and Anderson, 1997; Santiago and Erickson, 2002).

Similarly, semaphorins have been shown to play many important roles in embryonic development, in addition to their roles as axon guidance factors. Autocrine stimulation by class 3 semaphorins such as Sema3A and Sema3F modulates endothelial cell adhesive and migratory properties in angiogenesis (Serini et al., 2003). Signaling by Sema3E to plexin-D1 independent of neuropillin controls vascular patterning in the somites by limiting angiogenic sprouting (Gu et al., 2005). Class 3 semaphorins are essential for heart morphogenesis. Targeted mutation of Sema3C, Sema3A, or Plexin D1 in mice exhibits severe defects in various cardiac structures (Behar et al., 1996; Feiner et al., 2001; Gitler et al., 2004). In addition, Sema6D has been shown to play dual roles in cardiac morphogenesis, promoting migration of cells from the conotruncal segment, and inhibiting migration of ventricular cells (Toyofuku et al., 2004a). Reverse signaling by Sema6D enhances the migration of myocardial cells from the compact zone into the trabeculae (Toyofuku et al., 2004b). Semaphorins also additionally play a role in cell–cell interaction in the immune system, cancer formation, and metastasis (Kruger et al., 2005).

Although the expression patterns of semaphorins have been well documented in the development of the nervous systems (Shepherd et al., 1996; Chilton and Guthrie, 2003), expression analysis of semaphorin genes during early embryonic development is relatively limited. Here, we report characterization of a partial cDNA clone of the chick Sema7A gene, and its expression patterns in early embryonic development, in comparison to those of the Sema3D gene. Interestingly, these two genes exhibit largely non-overlapping, in some areas even complementary, expression patterns. In mesoderm-derived tissues, Sema3D transcripts were detected in the notochord, while Sema7A transcripts were detected in the newly formed somites. In the neural tube, Sema3D is expressed in forebrain, diencephalon, and dorsal neural tube in the spinal cord region, whereas Sema7A has only limited expression in the hindbrain. Sema3D is also expressed broadly in surface ectoderm, and ectodermal pla-codes such as lens placode and nasal placode. In the ectoderm of the limb bud, Sema7A is expressed predominantly in the apical ectodermal ridge (AER) where Sema3D expression is excluded, exhibiting complementary patterns. In addition, Sema3D appears to be expressed in cranial neural crest cells, but not in the trunk region. In contrast, Sema7A gene is broadly expressed in the neural crest cells including both cranial and trunk neural crest cells. These dynamic expression patterns suggest that these semaphorins may play distinct roles in early embryonic development.

RESULTS

Characterization of Chick Sema7A Partial cDNA Clone

Using cDNAs prepared from chick embryonic day 6 (E6) retinal and heart tissues as templates, we performed polymerase chain reactions (PCR) with degenerate primers, designed based on the conserved sequences in the SEMA domain, WTTFM(L)KA and DPYCA(G)WD (see Experimental Procedures section). We sequenced approximately 60 clones and analyzed the sequence by nucleotide and translated blast analyses using the programs provided by National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Several clones were confirmed as identical to the previously reported chick Sema3D gene (Luo et al., 1995; Chilton and Guthrie, 2003; Watanabe et al., 2004; Jin et al., 2006). Another clone was found to be identical to the newly annotated Sema7A gene from the chick genomic sequence (accession number: XM_413687), except a stretch of 44 nucleotides (Fig. 1A). This resulted in 16–amino acid sequence divergence in the SEMA domain. To distinguish it from the annotated Sema7A gene in the database, we named our clone “Sema7A-2.”

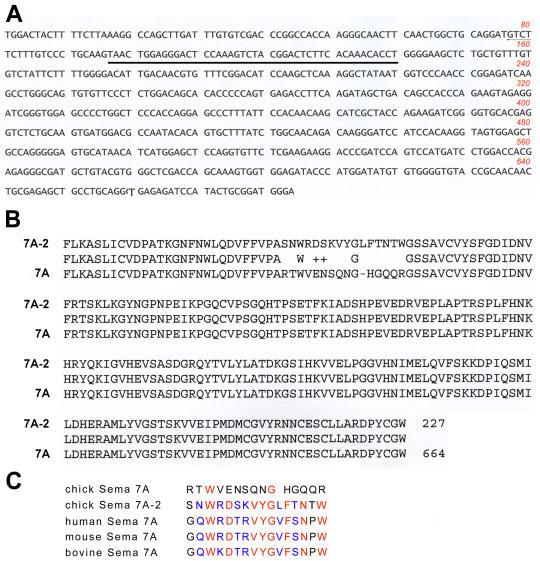

Fig. 1.

Sequence analysis of the Sema7A-2 clone. A: Nucleotide sequence of Sema7A-2. The 44-nucleotides that are different from the annotated Sema7A gene are underlined. B: Comparison of amino acid sequence translated from the Sema7A-2 sequence with that of the annotated Sema7A gene. Note that the amino acid sequence is identical except the16–amino acid stretch. C: Comparison of the 16–amino acid sequences encoded by human, mouse, bovine, and chick Sema7A genes with that by Sema7A-2. Note that the 16–amino acid sequence of the chick Sema7A-2 is more homologous to the mammalian Sema7A proteins than the annotated chick Sema7A.

To determine whether Sema7A-2 is a splice variant of the Sema7A gene, we performed blast searches in the expression sequence tag (EST) databases. Two chicken EST clones derived independently from a reproductive tract cDNA library (accession number CD217836) and a brain and testis library (accession number CN218431), respectively, show identical sequences to that of the Sema7A-2, including the divergent 44-nucleotide sequence. However, the 44-nucleotide sequence in the annotated chick Sema7A gene did not find its match in the EST databases. In addition, the 16–amino acid sequence translated from the 44 nucleotides in the Sema7A-2 clone appears to be highly homologous to the equivalent regions in the human, mouse, and bovine Sema7A genes (87.5% similarity). The 16–amino acid sequence in the annotated chick Sema7A gene, however, appears not conserved compared to that of the mammalian genes (12.5% similarity). These results suggest that the Sema7A-2 clone is likely a partial cDNA clone of the bona fide Sema7A gene. We currently do not know whether the 44-nucleotide sequence in the annotated chick Sema7A is expressed as a splice variant.

Expression of Sema3D and Sema7A Transcripts in Early Chick Embryonic Development

Further analysis with the bl2seq program provided by NCBI showed that Sema3D and Sema7A-2 clones are divergent, with only 45% similarity in amino acid sequence, and no significant conservations in nucleotide sequence. In addition, blast searches against the entire NCBI databases confirmed that the nucleotide sequences of the Sema3D and Sema7A-2 clones do not share significant identity with other genes, indicating that these cDNA clones can be used as templates for synthesizing specific probes for the chick Sema3D and Sema7A genes.

We carried out in situ hybridization experiments by using digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA probes synthesized by using the Sema3D and Sema7A-2 as templates. As the sequence of the Sema7A-2 is identical to the annotated Sema7A gene in 640 out of total 684 nucleotides, in situ hybridization by this probe should detect mRNA transcripts of both the Sema7A-2 and Sema7A genes, if they are expressed. We thus refer to the in situ hybridization patterns by this probe as the expression patterns of the Sema7A gene in the rest of this report. Multiple in situ hybridization experiments and negative controls with DIG-probes corresponding to the sense strand sequences were performed to ensure reproducibility and specificity.

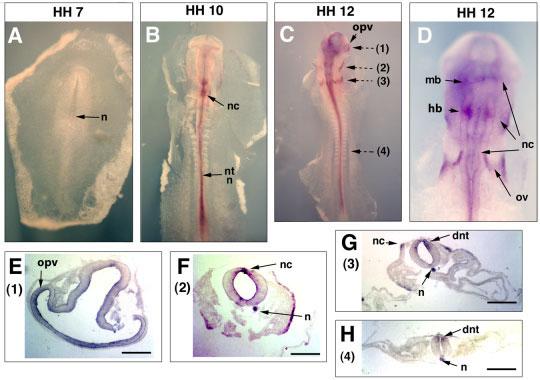

The Sema3D mRNA expression was detected as early as Hamburger-Hamilton (HH) stage 7 in the notochord (Hamburger and Hamilton, 1992), and high levels of expression in the notochord persist to HH12 (Fig. 2A-C, F–H). A moderate level of expression was detected in the neural tube at HH12, and in the forebrain, diencephalons, and dorsal neural tube in the trunk region (Fig. 2C-H). Also at HH12, Sema3D expression was observed in optical and otic vesicles (Fig. 2C-E), and in migrating neural crest cells in midbrain and hindbrain regions (Fig. 2D,F,G).

Fig. 2.

Expression of Sema3D in early chick embryos (HH7 to HH12). Dorsal sides of embryos are shown for whole mount in situ hybridization results. For sections, the dorsal sides of the embryons are oriented upward. Whole mount in situ hybridization results are shown for embryos of (A) HH7, (B) HH10, (C) HH12 at a low magnification, and (D) HH12 at a higher magnification. After whole mount in situ hybridization, the embryos were sectioned. The planes of sections were shown with broken arrows and the numbers in parentheses next to the arrows indicate the figures showing the section results. E–H: Results from four section planes (1–4) of the HH12 embryo are shown after in situ hybridization with the Sema3D probe. n, notochord; nc, neural crest; nt, neural tube; mb, midbrain; hb, hindbrain; ov, otic vescicle; opv, optic vescicle; dnt, dorsal neural tube. Scale bars = 100 μm.

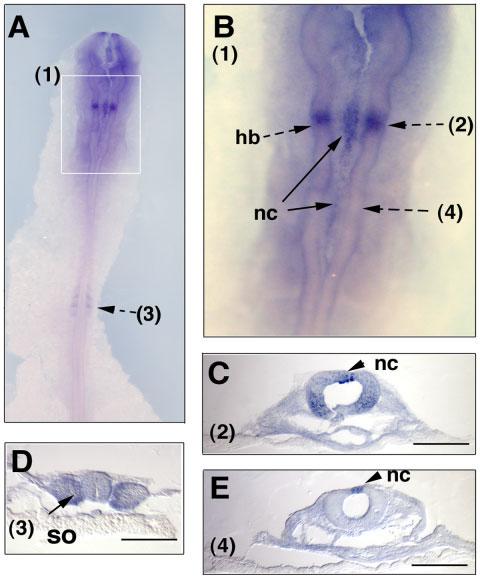

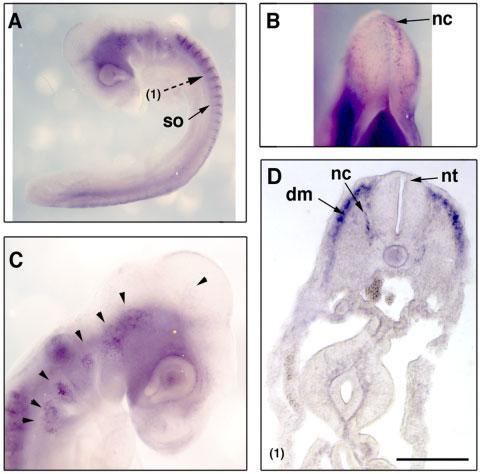

The expression of Sema7A was not detected before HH11–12. At HH12, Sema7A transcripts were found to be expressed in a restricted domain in the hindbrain (Fig. 3A,B), which on section, appear to be in the neuroepithelium in the medial portion of the neural tube (Fig. 3C). In addition, a group of cells in the dorsal midline are also positive for Sema7A (Fig. 3B). These cells are localized at the dorsal-most portion of the neural tube, corresponding to the premigratory neural crest cells in the hindbrain similar to the Slug gene (Del Barrio and Nieto, 2004) (Fig. 3C,E). In mesoderm-derived tissues, some expression was detected in the first 3–4 somites from the caudal side, but not in any of the rostral somites, suggesting that Sema7A is expressed only in the newly formed somites (Fig. 3A,D).

Fig. 3.

Expression of Sema7A transcripts in early chick embryos at HH12. HH12 chick embryos were hybridized with the Sema7A-2 RNA probe, shown at the dorsal side of the embryo (A) and in the hindbrain region (B). The boxed area (1) in A is shown at a higher magnification in B. Note its expression in a restricted domain in hindbrain region and in some premigratory neural crest cells at the dorsal midline of the neural tube. The embryos were sectioned after whole mount in situ hybridization at the indicated section planes (2)–(4). nc, neural crest, hb, hindbrain, so, somite. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Expression of Sema3D and Sema7A at HH Stage 17–18

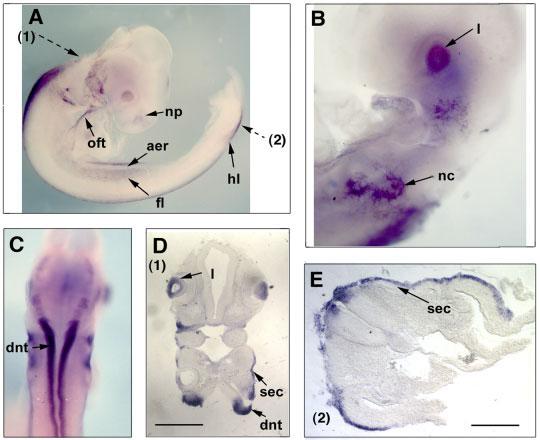

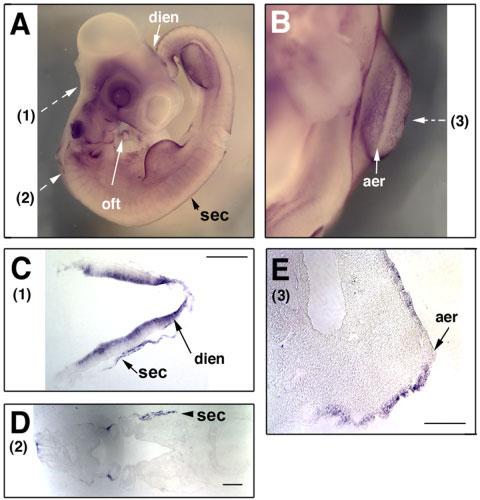

At HH17–18, the expression of Sema3D transcripts was visible widely in surface ectoderm and ectoderm-derived structures such as the lens placode and nasal placode (Fig. 4). Sema3D is additionally expressed in nascent limb bud and migrating neural crest cells. Interestingly, the expression in limb bud appears to be throughout the ectoderm except the apical ectodermal ridge (AER) region (Fig. 4A). Among the neural crest cells, Sema3D expression appears to be only in the cranial but not in the trunk neural crest (Fig. 4A,B, and E). Some Sema3D-positive cells were observed inside the heart in the outflow tract region. A high level of expression was also observed in the dorsal part of the neural tube, especially in the hindbrain and spinal cord regions (Fig. 4C-E).

Fig. 4.

Expression of Sema3D transcripts at HH stage 17. Lateral views (A, B) and a rear view (C) of the embryos are shown after whole mount in situ hybridization. The embryos were sectioned and the planes of sections are indicated by broken arrows. The numbers in parentheses next to the broken arrows indicate the figure numbers showing the section results. Note that the purple staining in the lens vesicles appears inside of the cells (D), suggesting that this is a signal of in situ hybridization, not trapping. aer, apical ectoderm ridge; np, nasal placode; fl, forelimb; hl, hindlimb; l, lens; nc, neural crest; oft, outflow tract; dnt, dorsal neural tube; sec, surface ectoderm. Scale bar in D = 250 μm, in E = 100 μm.

At the same stages, Sema7A expression was detected widely in the neural crest cells, migrating from various levels of the neural tube, including mid-brain, hindbrain, and the trunk regions (Fig. 5). On cross-section, Sema7A-positive cells were found in dermomyotome, ventral-medially migrating neural crest cells, but not in surface ectoderm. Unlike Sema3D, no visible in situ hybridization signal of Sema7A probe is present in the neuroepithelium in the neural tube (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Expression of Sema7A transcripts in HH17 chick embryos. Lateral views of the embryos (A, C) and a dorsal view of the midbrain/hindbrain regions (B) are shown. The section plane is indicated by a broken arrow and the section result is shown in D. Note the expression of Sema7A in migrating neural crest cells in cranial facial region (arrowheads in C) and in trunk region (D). so, somites; nc, neural crest; dm, dermomyotome; nt, neural tube. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Expression of Sema3D and Sema7A at HH Stage 22 (E3.5)

At E3.5 (HH22), Sema3D transcript expression persists broadly in surface ectoderm including most of the cranial facial and trunk regions (Fig. 6). In both the forelimb and hind limb, high levels of Sema3D transcripts were found in the surface ectoderm (Fig. 6B,E), but absent in the AER, similar to the patterns at HH17–18 (Fig. 4A). In the central nervous system, expression of Sema3D transcripts appears to be exclusively in the diencephalon (Fig. 6A,C). Similar to earlier stages, positive signals were also detected in the outflow tract region of the heart (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Expression of Sema3D transcripts in E3.5 chick embryos. A lateral view (A) and a frontal view in the forelimb bud area (B) are shown. Section planes are indicated by broken arrows and the results of the sections are shown in C–E. Note the staining in the otic vesicle in (A) is due to trapping. Dien, diencephalon; oft, outflow tract; aer, apical ectoderm ridge; sec, surface ectoderm. Scale bars = 100 μm.

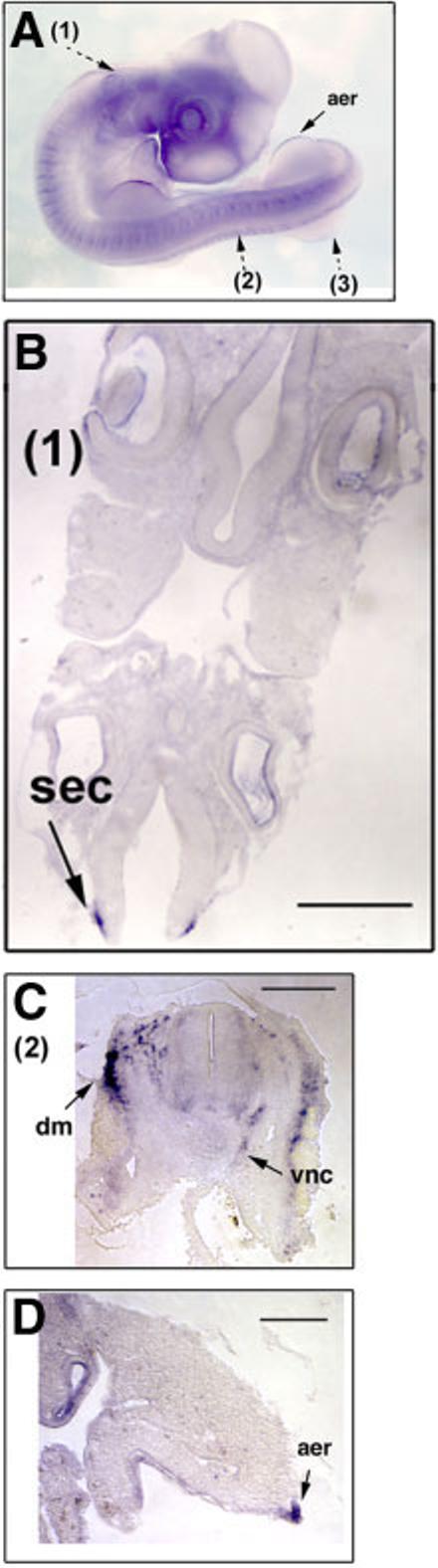

At E3.5, Sema7A transcript expression was observed in a different subset of ectoderm-derived tissues. The expression was still visible in the neural crest cells migrating via a dorsal-lateral route, as well as those via a ventral-medial route (Fig. 7C). Sema7A transcripts are not expressed in the neuroepithelium inside the neural tube. Except for the surface ectoderm next to the dorsal-most section of the neural tube in the hindbrain, there is no expression in the surface ectoderm elsewhere (Fig. 7B). The expression of Sema7A in the limb bud is complementary to that of Sema3D in that it is highly concentrated in AER, but not in the other regions of the limb bud.

Fig. 7.

Expression of Sema7A transcripts in E3.5 chick embryos. A: In situ hybridizations were performed on whole mount E3.5 chick embryos. Section planes are shown with broken arrows and the results of section after in situ hybridization are shown in B–D (1–3). aer, apical ectodermal ridge; sec, surface ectoderm; dm, dermomyotome; nc, dorsal-laterally migrated neural crest cells; vnc, ventral-medially migrated neural crest cells. Scale bars = 100 μm.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report isolation of a partial cDNA clone of the chick Sema7A gene, and expression analysis of Sema7A and Sema3D genes in early chick embryonic development. Interestingly, transcripts of these two semaphorin genes are mostly expressed in the areas with active morphogenesis and cell migration. In addition, the expression patterns of Sema7A and Sema3D transcripts appear largely non-overlapping, even complementary in some areas such as the limb bud.

Except for a stretch of 44 nucleotides, Sema7A-2 sequence is identical to the annotated chick Sema7A (640 out of total 684 nucleotides). However, the divergent 44-nucleotide sequence in Sema7A-2 is identical to the sequences from two independent chicken Sema7A EST clones, and the translated amino acid sequence of Sema7A-2 is highly homologous to those in the mammalian Sema7A proteins, suggesting that the Sema7A-2 clone is the partial cDNA clone of the bona fide Sema7A gene. Because we failed to find any matching EST clone, we currently do not know whether the annotated chick Sema7A gene in the database is expressed and represents a splice variant of the gene.

Although initially characterized as axon guidance molecules (Raper, 2000; Pasterkamp and Kolodkin, 2003), semaphorins have been shown to play a role in cell migration, tissue morphogenesis, and remodeling. The best examples may be their roles in heart development. Targeted mutation of Sema3C in mice exhibit severe cardiac defects consisting of interruption of the aortic arch and improper septation of the cardiac outflow tract (Feiner et al., 2001). Sema3A−/− mutant mice have postnatal hypertrophy of the right ventricle and ventricular septal defect (Behar et al., 1996). Deletion of one of the plexin receptors, plexinD1, results in cardiovascular defects involving the outflow tract of the heart and derivatives of the aortic arch arteries (Gitler et al., 2004). In addition, Sema6D has been shown to play dual roles in cardiac morphogenesis, promoting migration of cells from the conotruncal segment and inhibiting migration of ventricular cells (Toyofuku et al., 2004a). Reverse signaling by Sema6D enhances the migration of myocardial cells from the compact zone into the trabeculae (Toyofuku et al., 2004b). More recently, Sema3D, Sema3F, and Sema5A are shown to be expressed in cardiac cushions, an area characterized by active epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and remodeling (Jin et al., 2006). Sema3D is additionally expressed in the motile cells at the tips of ventricular trabeculae. These results suggest that semaphorins are expressed in the areas with active morphogenesis and possibly play a role in cell migration and embryogenesis.

Sema3F has been shown to be expressed in the posterior-half of the somites and repels trunk neural crest from migrating in the posterior half of the somites (Gammill et al., 2006) and Sema3A is required for correct migration of neural crest cells and patterning of the sympathetic nervous system (Eickholt et al., 1999; Kawasaki et al., 2002). Repulsion from the Sema3 molecules also contributes to the guidance of migrating cranial neural crest cells (Osborne et al., 2005; Yu and Moens, 2005). Sema3C/plexin A2 interaction has been shown to be crucial for the migration and entry of the neural crest cells into the heart (Brown et al., 2001; Feiner et al., 2001). We detected some signals of Sema3D transcripts in the dorsal-most portion of the neural tube, corresponding to the premigratory neural crest cells, as well as in migrating cranial neural crest. This is similar to the previous finding that Sema3D is expressed in the motile cells at the tips of trabeculae in the ventricular chamber of the heart (Jin et al., 2006). As Sema3D encodes a secreted protein, its role in motile cells is currently unclear. It has been demonstrated that SemaA3 controls vascular morphogenesis by inhibiting integrin function in an autocrine manner (Serini et al., 2003). Disruption of SemaA3 signaling stimulates integrin-mediated adhesion and migration to extracellular matrices.

In early embryonic development, Sema7A is expressed in specific domains in the neural tube, limb bud, and somites. However, Sema7A is widely expressed in the migrating neural crest cells. Unlike the class 3 semaphorin genes, Sema7A encodes a membrane-anchored protein. In contrast to most semaphorin proteins, which act as negative factors for axonal growth and guidance, Sema7A enhances central and peripheral axon growth and is required for the proper formation of axonal tract during embryonic development (Pasterkamp et al., 2003). In addition, the positive effect of Sema7A on axonal growth requires integrin receptor and MAPK signaling pathways. Moreover, Sema7A has been shown to be a potent stimulator of monocytes. Sema7A is expressed in the monocytes and acts by releasing through proteolysis in an autocrine fashion (Holmes et al., 2002). It awaits further study to uncover how these semaphorin genes are involved in cell migration and morphogenesis during early embryonic development.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning of Partial cDNAs of the Chick Semaphorin Genes

Total RNAs were isolated from chick E6 heart and retinal tissues using Trizol (Invitrogen, La Jolla, CA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using oligo (dT)12–18 primer and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Subsequent PCR reactions were carried out with degenerate forward and reverse primers designed based on the conserved amino acid sequences in the SEMA domain, WTTFM(L)KA and DPYCA(G)WD, respectively. An EcoRI restriction site was added to the forward primer, and a XhoI site was added to the reverse primer for cloning into the pBluescript vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The sequences of the forward and reverse primers are: 5′-GGAATTCTGGACXACXTTYHTXAARGC (X=A+G+C+T, Y=C+T, H=C+T+A, R=A+G, S=G+C) and 5′-GCTCGAGTCCCAXSCRCARTAXGGRTC, respectively. The expected PCR product (700–750 bp) was cut out from the gel and subcloned into the pBluescript vector. The clones were analyzed by microsequencing and blast searches using programs of nucleotide-nucleotide BLAST and translated query vs. protein database provided by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The databases searched include non-redundant nucleotide sequence databases, EST databases, and non-redundant peptide sequence databases (NCBI). In addition, sequence similarity among the two genes was analyzed pairwise by using the bl2seq programs (blastn and tblastx) (NCBI). The sequence of Sema7A-2 has been deposited in the GenBank (accession number DQ525915).

In Situ Hybridization

Standard specific pathogen-free white Leghorn chick embryos from closed flocks were provided fertilized by Charles River Laboratories (North Franklin, CT). Eggs were incubated inside a moisturized 38°C incubator and staged according to Hamburger and Hamilton (1992).

The sense and anti-sense RNA probes for Sema3D and Sema7A were synthesized by in vitro transcription with T3 or T7 RNA polymerases using digoxigenin-labeled UTPs (Roche). The procedure of whole mount in situ hybridization was carried out essentially as previously described (Jin et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2004). Chick embryos of HH5, HH7–10, HH12 (∼E1.5), HH17–18 (E2.5), and HH22 (E3.5) were dissected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 12–24 hr. The embryos were treated with Proteinase K (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) with increasingly higher concentrations for the older embryos, at 1 μg/ml for embryos younger than HH10, 5 μg/ml for HH12–17, and 10 μg/ml for embryos older than HH17. Hybridization was carried out by incubation with probes (∼1 μg/ml) in the hybridization buffer (50% Formamide, 5×SSC, pH 4.5, 50 μg/ml yeast RNA, 1% SDS, 50 μg/ml heparin) overnight at 70°C. After hybridization, three washes were carried out for 30 min at 70°C with buffer I (50% formamide, 5×SSC, pH 4.5, 1% SDS) followed by three washes at 65°C with buffer III (50% formamide, 2×SSC, pH 4.5).

After completion of whole mount in situ hybridization, some of the embryos were sectioned. The embryos were postfixed in 4% paraformalde-hyde and rinsed with PBS. The embryos were incubated in 15% sucrose in PBS with gentle rocking at 4°C for 24 hr. The embryos were then embedded in 15% sucrose, 7.5% gelatin in PBS, and sectioned on a cryostat (Leica, Deerfield, IL). The tissue sections were collected on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and mounted. Results of whole mount in situ hybridization were photographed with a digital camera coupled to a dissection microscope (Nikon). The results of section in situ hybridization were observed on an upright microscope (Nikon TE 400) and photographed with a digital SPOT camera.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jinhua Zhang for technical assistance and Dr. Charles Sager-strom for helpful advice and discussion.

Footnotes

Grant sponsor: American Heart Association; Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Grant number: EY014980.

REFERENCES

- Behar O, Golden JA, Mashimo H, Schoen FJ, Fishman MC. Semaphorin III is needed for normal patterning and growth of nerves, bones and heart. Nature. 1996;383:525–528. doi: 10.1038/383525a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CB, Feiner L, Lu MM, Li J, Ma X, Webber AL, Jia L, Raper JA, Epstein JA. PlexinA2 and semaphorin signaling during cardiac neural crest development. Development. 2001;128:3071–3080. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilton JK, Guthrie S. Cranial expression of class 3 secreted semaphorins and their neuropilin receptors. Dev Dyn. 2003;228:726–733. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Barrio MG, Nieto MA. Relative expression of Slug, RhoB, and HNK-1 in the cranial neural crest of the early chicken embryo. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:136–139. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin L, Brennan C, Shiomi K, Cooke J, Barrios A, Shanmugalingam S, Guthrie B, Lindberg R, Holder N. Eph signaling is required for segmentation and differentiation of the somites. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3096–3109. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.3096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickholt BJ, Mackenzie SL, Graham A, Walsh FS, Doherty P. Evidence for collapsin-1 functioning in the control of neural crest migration in both trunk and hindbrain regions. Development. 1999;126:2181–2189. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.10.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiner L, Webber AL, Brown CB, Lu MM, Jia L, Feinstein P, Mombaerts P, Epstein JA, Raper JA. Targeted disruption of semaphorin 3C leads to persistent truncus arteriosus and aortic arch interruption. Development. 2001;128:3061–3070. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammill LS, Gonzalez C, Gu C, Bronner-Fraser M. Guidance of trunk neural crest migration requires neuropilin 2/semaphorin 3F signaling. Development. 2006;133:99–106. doi: 10.1242/dev.02187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerety SS, Wang HU, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ. Symmetrical mutant pheno-types of the receptor EphB4 and its specific transmembrane ligand ephrin-B2 in cardiovascular development. Mol Cell. 1999;4:403–414. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitler AD, Lu MM, Epstein JA. PlexinD1 and semaphorin signaling are required in endothelial cells for cardiovascular development. Dev Cell. 2004;7:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieshammer U, Le M, Plump AS, Wang F, Tessier-Lavigne M, Martin GR. SLIT2-mediated ROBO2 signaling restricts kidney induction to a single site. Dev Cell. 2004;6:709–717. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu C, Yoshida Y, Livet J, Reimert DV, Mann F, Merte J, Henderson CE, Jessell TM, Kolodkin AL, Ginty DD. Semaphorin 3E and plexin-D1 control vascular pattern independently of neuropilins. Science. 2005;307:265–268. doi: 10.1126/science.1105416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V, Hamilton HL. A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. Dev Dyn. 1992;195:231–272. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001950404. 1951 (see comments) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinck L. The versatile roles of “axon guidance” cues in tissue morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2004;7:783–793. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes S, Downs AM, Fosberry A, Hayes PD, Michalovich D, Murdoch P, Moores K, Fox J, Deen K, Pettman G, Wattam T, Lewis C. Sema7A is a potent monocyte stimulator. Scand J Immunol. 2002;56:270–275. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2002.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, Zhang J, Klar A, Chedotal A, Rao Y, Cepko CL, Bao ZZ. Irx4 regulation of Slit1 expression contributes to the definition of early axonal paths inside the retina. Development. 2003;130:1037–1048. doi: 10.1242/dev.00326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, Chau MD, Bao ZZ. Sema3D, Sema3F, and Sema5A are expressed in overlapping and distinct patterns in chick embryonic heart. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:163–169. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki T, Bekku Y, Suto F, Kitsukawa T, Taniguchi M, Nagatsu I, Nagatsu T, Itoh K, Yagi T, Fujisawa H. Requirement of neuropilin 1-mediated Sema3A signals in patterning of the sympathetic nervous system. Development. 2002;129:671–680. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.3.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger RP, Aurandt J, Guan KL. Semaphorins command cells to move. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:789–800. doi: 10.1038/nrm1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull CE, Lansford R, Gale NW, Collazo A, Marcelle C, Yancopoulos GD, Fraser SE, Bronner-Fraser M. Interactions of Eph-related receptors and ligands confer rostrocaudal pattern to trunk neural crest migration. Curr Biol. 1997;7:571–580. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Shepherd I, Li J, Renzi MJ, Chang S, Raper JA. A family of molecules related to collapsin in the embryonic chick nervous system. Neuron. 1995;14:1131–1140. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne NJ, Begbie J, Chilton JK, Schmidt H, Eickholt BJ. Semaphorin/neuropilin signaling influences the positioning of migratory neural crest cells within the hindbrain region of the chick. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:939–949. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasterkamp RJ, Kolodkin AL. Semaphorin junction: making tracks toward neural connectivity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:79–89. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasterkamp RJ, Peschon JJ, Spriggs MK, Kolodkin AL. Semaphorin 7A promotes axon outgrowth through integrins and MAPKs. Nature. 2003;424:398–405. doi: 10.1038/nature01790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper M, Little M. Movement through Slits: cellular migration via the Slit family. Bioessays. 2003;25:32–38. doi: 10.1002/bies.10199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poliakov A, Cotrina M, Wilkinson DG. Diverse roles of eph receptors and ephrins in the regulation of cell migration and tissue assembly. Dev Cell. 2004;7:465–480. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raper JA. Semaphorins and their receptors in vertebrates and invertebrates. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:88–94. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago A, Erickson CA. Ephrin-B ligands play a dual role in the control of neural crest cell migration. Development. 2002;129:3621–3632. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.15.3621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serini G, Valdembri D, Zanivan S, Morterra G, Burkhardt C, Caccavari F, Zammataro L, Primo L, Tamagnone L, Logan M, Tessier-Lavigne M, Taniguchi M, Puschel AW, Bussolino F. Class 3 semaphorins control vascular morphogenesis by inhibiting integrin function. Nature. 2003;424:391–397. doi: 10.1038/nature01784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd I, Luo Y, Raper JA, Chang S. The distribution of collapsin-1 mRNA in the developing chick nervous system. Dev Biol. 1996;173:185–199. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan K, Strickland P, Valdes A, Shin GC, Hinck L. Netrin-1/neogenin interaction stabilizes multipotent progenitor cap cells during mammary gland morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2003;4:371–382. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyofuku T, Zhang H, Kumanogoh A, Takegahara N, Suto F, Kamei J, Aoki K, Yabuki M, Hori M, Fujisawa H, Kikutani H. Dual roles of Sema6D in cardiac morphogenesis through region-specific association of its receptor, Plexin-A1, with off-track and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor type 2. Genes Dev. 2004a;18:435–447. doi: 10.1101/gad.1167304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyofuku T, Zhang H, Kumanogoh A, Takegahara N, Yabuki M, Harada K, Hori M, Kikutani H. Guidance of myocardial patterning in cardiac development by Sema6D reverse signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2004b;6:1204–1211. doi: 10.1038/ncb1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HU, Anderson DJ. Eph family transmembrane ligands can mediate repulsive guidance of trunk neural crest migration and motor axon outgrowth. Neuron. 1997;18:383–396. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HU, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ. Molecular distinction and angiogenic interaction between embryonic arteries and veins revealed by ephrin-B2 and its receptor Eph-B4. Cell. 1998;93:741–753. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Toyoda R, Nakamura H. Navigation of trochlear motor axons along the midbrain-hindbrain boundary by neuropilin 2. Development. 2004;131:681–692. doi: 10.1242/dev.00970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong K, Park HT, Wu JY, Rao Y. Slit proteins: molecular guidance cues for cells ranging from neurons to leukocytes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:583–591. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Mellitzer G, Robinson V, Wilkinson DG. In vivo cell sorting in complementary segmental domains mediated by Eph receptors and ephrins. Nature. 1999;399:267–271. doi: 10.1038/20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yebra M, Montgomery AM, Diaferia GR, Kaido T, Silletti S, Perez B, Just ML, Hildbrand S, Hurford R, Florkiewicz E, Tessier-Lavigne M, Cirulli V. Recognition of the neural chemoattractant Netrin-1 by integrins alpha6beta4 and alpha3beta1 regulates epithelial cell adhesion and migration. Dev Cell. 2003;5:695–707. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu HH, Moens CB. Semaphorin signaling guides cranial neural crest cell migration in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2005;280:373–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Jin Z, Bao ZZ. Disruption of gradient expression of Zic3 resulted in aberrant projection of the retinal ganglion axons to the optic disc. Development. 2004;131:1553–1562. doi: 10.1242/dev.01041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]