Abstract

The harmful effects of pregnancy-associated malaria (PAM) are engendered by the heavy sequestration of Plasmodium falciparum-parasitized RBCs in the placenta. It is well documented that this process is mediated by interactions of parasite-encoded variant surface antigens and placental receptors. A P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 variant, VAR2CSA, and the placental receptor chondroitin sulfate A (CSA) are currently the focus of PAM research. A role for immunoglobulins (IgG and IgM) from normal human serum and hyaluronic acid as additional receptors in placental sequestration have also been suggested. We show here (i) that CSA and nonimmune IgG/IgM binding are linked phenotypes of in vitro-adapted parasites, (ii) that a VAR2CSA variant shown to bind CSA also harbors IgG- and IgM-binding domains (DBL2-X, DBL5-ε, and DBL6-ε), and (iii) that IgG and IgM binding and adhesion to multiple receptors (IgG/IgM/HA/CSA) rather than the exclusive binding to CSA is a characteristic of fresh Ugandan placental isolates. These findings are of importance for the understanding of the pathogenesis of placental malaria and have implications for the ongoing efforts to develop a global PAM vaccine.

Keywords: placental sequestration, receptors, var2csa, PfEMP1

In high transmission areas, severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria is mainly a childhood disease. Adults are usually immune to clinical malaria because of repeated infections and a gradual acquisition of protective immunity. Pregnant women and, in particular, primigravidae are, however, an exception. With a yearly exposure to malaria of at least 50 million pregnancies, this is the most recurrent parasitic infection directly affecting the placenta (1). Sequestration of late-stage parasitized RBCs (pRBCs) (trophozoites) in the deep microvasculature of various organs is the hallmark of severe P. falciparum malaria. Interactions between variant parasite antigens expressed on the surface of pRBCs with endothelial host receptors (cytoadhesion) or receptors on normal RBCs (rosetting) are thought to be essential in this process. Hitherto, the PfEMP1 family of polymorphic and high-molecular-weight proteins encoded by the var genes (≈60 copies per genome) has been assigned as the main adhesin involved in sequestration (2).

Pregnancy-associated malaria (PAM) is characterized by the massive sequestration of P. falciparum pRBCs in placental intervillous spaces, causing inflammatory responses and deposition of fibrinoid material with maternal anemia and low birth weight as the main clinical consequences (3, 4). The adverse effects of PAM decrease with succeeding pregnancies and have been linked to the development of protective antibodies that recognize an antigenically and functionally distinct subpopulation of pRBCs (5–7). Whereas parasites from nonpregnant individuals interact with CD36 and several other receptors (8, 9), the glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chondroitin sulfate A (CSA) has been described as the main placental receptor (5, 10). Recent observations imply that structurally distinct var genes, var2CSA, encode the CSA-binding PfEMP1 variant implicated in PAM, raising hope for the development of a vaccine (11–14). There are, however, reports pinpointing the possible role of other receptors in placental sequestration. Hyaluronic acid (HA), yet another GAG, has been reported to interact with placental isolates (15). Some isolates bind solely to HA, whereas others interact with both HA and CSA. We have suggested that nonimmune Igs, in particular IgGs, may mediate placental sequestration by bridging pRBCs to IgG-binding receptors in the placenta (16). Much of the work, however, was based on an in vitro-adapted parasite clone (TM284S2). Another study demonstrated a link between IgM- and CSA-binding using laboratory parasites panned on bovine CSA (17). As yet, the involvement of IgM and IgG in the sequestration of clinical placental isolates is unknown, and parasite ligands engaged in adhesion to HA, IgG, and IgM have not been identified.

It is known that pRBCs of isolates from children with severe malaria have the capacity to interact with multiple receptors, and PfEMP1 variants having multiple adhesive domains have been reported (8, 18). Therefore, we reasoned that it is possible that placental isolates have similarly adopted alternative adhesion/evasion strategies. This hypothesis and the curiosity to further investigate the involvement of nonimmune IgG and IgM in placental malaria led us to conduct the present study. We show that not only IgM but also IgG is linked to CSA-binding in laboratory parasites implicated in pregnancy and that a VAR2CSA variant, previously shown to exhibit CSA-binding domains, also encompasses IgG- and IgM-binding domains. Moreover, by exploiting fresh Ugandan placental isolates, we provide data on the involvement of IgG, IgM, CSA, and HA as placental receptors. The data presented herein support the notion that multiple receptors account for parasite sequestration in the placenta.

Results

Laboratory Isolates Used for Ig-Binding Profiling.

In vitro-propagated parasites with a CSA-binding phenotype and/or recognized in a sex-specific manner by sera from malaria-endemic areas are commonly exploited as models for parasites implicated in pregnancy malaria. To study the involvement of IgG/IgM-binding in placental malaria, we commenced our investigation on seven in vitro-adapted laboratory isolates and their CSA-selected counterparts (Table 1). After multiple rounds of panning of the parental lines on bovine CSA, CSA-adhesive sublines were obtained (>500 infected RBCs bound per mm2). The parasites were also characterized for their ability to recognize sera from malaria-endemic areas in a sex-specific manner (Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Consistent with previous observations, pRBCs from the parental lines did not bind CSA and were similarly recognized by sera from men and multigravid women living in malaria endemic areas, whereas CSA-adhering sublines were differentially recognized by serum IgG from multigravid women relative to serum IgG from malaria-exposed men (19). Occasionally, unselected Gb337 was recognized by some sera from multigravid women in a sex-specific manner (data not shown).

Table 1.

Characteristics of laboratory parasites

| Parasite | Origin | CSA adhesion | Sex specificity | Ig-binding pRBCs, % mean ± SD* | IgM-binding pRBCs, % mean ± SD (MFI)* | IgG-binding pRBCs, % mean ± SD (MFI)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCR3 | Gambia | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FCR3CSA | Yes | Yes | 68 ± 9 | 41 ± 12 (++) | 26 ± 8 (+) | |

| Busua | Ghana | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BusuaCSA | Yes | Yes | 50 ± 8 | 30 ± 5 (++) | 23 ± 6 (+) | |

| SD2O2 | Sudan | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SD2O2CSA | Yes | Yes | 34 ± 7 | ND | ND | |

| NF54 | Netherlands | No | No | 15 ± 11 | 0 | 0 |

| NF54CSA | Yes | Yes | 45 ± 2 | ND | ND | |

| Gb337 | Gabon | No | Yes | 42 ± 5 | 30 ± 7 (++) | 11 ± 3 (+) |

| Gb337CSA | Yes | Yes | 74 ± 6 | 36 ± 8 (++) | 37 ± 3 (+) | |

| VIP43 | Senegal | No | ND | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| VIP43CSA | Yes | ND | 79 ± 6 | 26 ± 7 (++) | 29 ± 8 (+) | |

| ChC03 | Gabon | No | ND | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ChC03CSA | Yes | ND | 67 ± 2 | 39 ± 1 (++) | 43 ± 5 (+) |

ND, not determined; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

*Mean of three consecutive assays.

CSA Selection vs. Nonimmune Ig Binding.

To assess the binding of nonimmune human Igs to the pRBC surface of CSA-selected and -unselected laboratory isolates, live surface immunofluorescence assays (SIFA) were performed. Binding to Igs, as present in culture medium, was studied by using direct labeling with FITC anti-human Ig and indirect labeling with monoclonal anti-human IgG(Fc) and IgM antibodies. In all experiments, the isotype controls and the secondary antibody background controls were negative. Clear dotted fluorescence with the anti-Ig, -IgM, and -IgG reagents was observed only on late-stage trophozoite-infected RBCs and was then regarded as a specific positive signal. Upon CSA selection, there was a concomitant increase in Ig binding in all of the isolates (Table 1). The mean fluorescence rate of Ig binding increased from 8% (±16) in the unselected parental lines to 60% (±17) in their CSA-selected counterparts. The mean fluorescence rate of IgM binding increased from 6% (±13) to 34% (±6) and IgG binding from 2% (±5) to 32% (±8). The mean fluorescence intensity for IgG was weaker than for IgM and never in the range of signals observed in our reference parasite, TM284S2 (Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). In FCR3CSA, BusuaCSA, VIP43CSA, and ChC03CSA, both IgM and IgG accounted for the enhanced Ig binding. In Gb337CSA, the CSA selection resulted in an increase in IgG binding only (37 ± 3%); IgM binding was also present (36 ± 8%) but to the same level as in the parental line (30 ± 7%). Gb337 was also the only unselected parasite that was recognized by some sera in a sex-specific manner. Our data demonstrate a clear linkage between the two phenotypes (CSA vs. Ig binding). From previous data on the expression of only one PfEMP1 species on the pRBC surface, the possibility is raised that the linked phenotypes are mediated by the same surface ligand.

3D7VAR2CSA Harbors IgG- and IgM-Binding Domains.

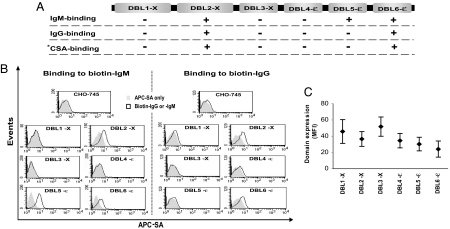

The transcriptional up-regulation of var2CSA in CSA-selected parasites including NF54CSA, SD2O2CSA, and FCR3CSA (11, 13) and the recent identification of CSA-binding domains in this molecule (12) (Fig. 1A) led us to investigate the Ig-binding capacity of 3D7VAR2CSA domains. We used stable transfectants expressing the various domains on the surface of CHO-745 cells and performed binding assays to biotin-labeled human IgG and IgM, followed by allophycocyanin–streptavidin (APC-SA) labeling and flow-cytometric analysis. Three domains, DBL2-X, DBL5-ε, and DBL6-ε, bound human IgM, whereas IgG binding was observed only with DBL2-X and DBL6-ε (Fig. 1B). Ig binding was never observed with untransfected cells and cells transfected with other domains. At least three independent experiments per Ig isotype and transfectant were performed with similar outcomes. By monitoring the domain expression level of all of the transfectants during each run, we could ascertain that the observed binding to IgM or IgG was not simply an effect of higher domain expression level in these particular transfectants (Fig. 1C). Binding of IgM to DBL5-ε resulted consistently in a higher fluorescence signal than signals obtained with IgM vs. DBL2-X and DBL-6ε (Fig. 1B). This finding can, in part, be explained by the somewhat lower DBL6-ε expression on the cell surface (Fig. 1C). The expression of DBL2-X was, however, somewhat higher than DBL5-ε. Another probable explanation is that higher numbers of potential Ig-binding motifs are present in the DBL5-ε domain, promoting high-avidity interactions with the pentameric IgM molecules. No such difference was observed in the IgG-binding level of DBL2-X vs. DBL6-ε.

Fig. 1.

Assessment of the nonimmune Ig-binding properties of 3D7 VAR2CSA domains by FACS. (A) Domain structure of 3D7 VAR2CSA. IgG- and IgM-binding domains as well as previously identified CSA-binding domains are indicated. (B) Data shown are flow-cytometric analyses of IgG- and IgM-binding properties of CHO-745 transfectants expressing various domains of 3D7var2CSA demonstrated as overlay histograms. Data are representative of more than three experiments. (C) The mean level of domain expression of each transfectant during all experimental runs is summarized and expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). In each transfectant, >90% of the cells stably expressed their respective domains (data not shown). ∗, CSA-binding domains were previously identified by Gamain et al. (17) using CHO-745 transfectants. APC-SA, allophycocyanin–streptavidin.

Patient Characteristics.

RBCs sequestered in the placentas of Ugandan women (n = 24) delivering at Mulago Hospital, Kampala, were isolated and analyzed immediately for their receptor-adhesion profile (IgG, IgM, HA, and CSA) by using an ex vivo placental adhesion/inhibition assay and SIFA. Preliminary data suggest that the prevalence of placental malaria among mothers delivering at the Mulago labor suite is ≈14%, with up to 60% prevailing in primigravidae. Accordingly, 67% (n = 16) of the placental isolates analyzed here originated from primigravidae. The mean age of the subjects was 20 years [interquartile range (IQR) = 18–24], and the majority were residents of Kampala (71%; n = 15). All placentas were actively infected by P. falciparum, as assessed by histological evaluation. Microscopic blood-film examination revealed a mean placental parasitemia level of 4% (IQR = 1–15.4%). For detailed information and analysis of patient characteristics see Supporting Results in Supporting Text and Tables 3 and 4, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Adhesion to IgG Alongside CSA and HA in Fresh Placental Field Isolates.

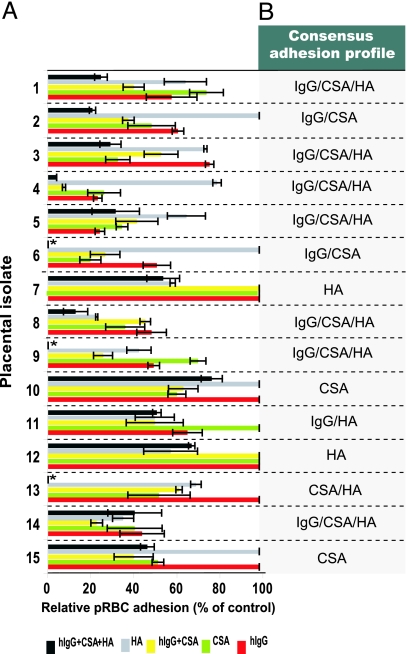

Ex vivo placental adhesion/inhibition assays were used to assess the receptor adhesion profile (IgG, HA, and CSA) of the isolates. Competition assays were performed by incubating pRBCs from each isolate with a saturating amount of IgG or CSA before adhesion to fresh placental cryosections. HA binding was assessed by enzymatic removal of the receptor subset from the placental section before pRBC adhesion. Eluted parasitemia of the isolates used in the assays ranged from 2% to 50% (geometric mean = 5%). RBCs from all of the isolates adhered to syncytiotrophoblast surfaces and intervillous spaces of the uninfected placental sections (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Binding of isolates in the absence of soluble competitor or enzymatic treatment (positive controls) ranged from 100 to 1,300 pRBCs per mm2, with a geometric mean of 220 pRBCs per mm2. The inhibition level with BSA alone (negative background control) was negligible in most isolates (mean = 7%; range = 0–15%). Preincubation with IgG alone inhibited the placental pRBC adhesion of 65% (11 of 17) of the isolates with a mean inhibition level (MIL) of 51% (range = 24–77%), whereas preincubation with CSA or HAase treatment inhibited the pRBC adhesion of 82% (14 of 17; MIL = 53%; range = 25–80%) and 73% (11 of 15; MIL = 43%; range = 20–77%) of the isolates, respectively (details in Table 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These figures indicate the presence of mixed/overlapping receptor-binding pRBC populations per isolate. To further analyze the receptor adhesion repertoire, isolates with complete set of adhesion data (isolates 1–15) were selected (Fig. 2A). Six different consensus adhesion profiles were identified (Fig. 2B). Isolates capable of interacting with all three receptors (IgG/CSA/HA) represented the dominant profile (47%; n = 7). The pRBCs of the remaining isolates interacted with two (n = 4; IgG/HA IgG/CSA or CSA/HA) or a single receptor (n = 4; CSA or HA).

Fig. 2.

Receptor-adhesion profile of Ugandan P. falciparum placental isolates. Freshly eluted pRBCs from infected placentas (n = 15) were examined for binding to various receptors by using ex vivo placental adhesion/inhibition assays. Binding to CSA and human IgG was assessed by preincubating the pRBCs with saturating concentrations of the soluble receptors before placental binding. The involvement of HA was assessed by enzymatically removing the receptor subset from the placental section before pRBC adhesion using Streptomyces HAse. (A) The diagram illustrates the level of pRBC adhesion to placental section for each isolate after treatment with IgG alone, CSA alone, a combination of both (IgG plus CSA), HAse alone, and a combination of all three treatments (IgG plus CSA plus HAse). Adhesion level is expressed as the percentage of positive control (no treatment). Each isolate was tested in duplicate or triplicate for each receptor or receptor combination. (B) The consensus receptor-adhesion profile of each isolate is indicated. ∗, Not tested for the IgG plus CSA plus HAse combination.

Preincubation of pRBCs with a combination of IgG and CSA alongside HAase treatment of the placental section (IgG plus CSA plus HAse) abrogated the placental adhesion of the multiadhesive isolates (IgG/CSA/HA; MIL = 76 ± 13%; Fig. 2A). Hence, the main bulk of the pRBC populations in these isolates contributed to the observed receptor-binding profile. In other isolates, in particular those interacting with a single receptor, approximately half of the pRBC population per isolate was engaged in the observed adhesion profile (MIL = 43 ± 4%). This finding could imply that the remaining pRBC populations adhere to the placenta by means of interactions with presently unknown receptors. In most isolates (Fig. 2A; isolates 1–5, 8, and 14), inhibition with IgG and CSA in combination (IgG plus CSA) did not yield significantly higher inhibition levels as compared with inhibition with each of the receptors alone. This finding implies that the same subpopulation interacts with both receptors, fortifying previous observations on CSA-panned parasite lines.

Nonimmune Ig-Binding Profile of Fresh Placental Isolates.

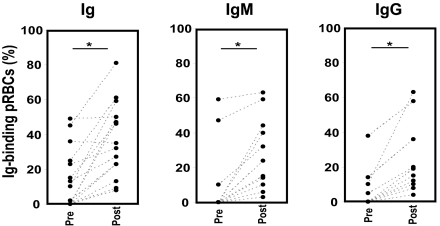

The IgG- and IgM-binding profiles of the isolates were further analyzed with SIFA by using basically the same procedure as for the in vitro-adapted parasites. Yet, unlike laboratory isolates, grown solely in malaria-naïve serum, the freshly eluted patient isolates originate from an environment where both nonimmune Igs, and perhaps specific Igs as a result of specific immune response, are present. Another difference between the assays is that the field isolates were eluted from placentas with PBS-EDTA, a chelating agent. We know from experience on Ig-binding laboratory parasites that PBS-EDTA strips off surface-bound Igs to varying degrees in different parasites (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). However, incubation of the parasites with 50% malaria-naïve serum for 1 h at 37°C seems to be sufficient for the reconstitution of the original Ig-binding level. Hence, to ascertain the assessment of the complete nonimmune Ig-binding level of each isolate, all isolates were screened with anti-Ig (n = 22), -IgM (n = 21), and -IgG (n = 21) reagents both directly upon elution from placenta (preserum) and after 1 h of incubation with 50% malaria-naïve serum (postserum). As expected, the proportion of Ig-positive isolates in postserum groups was markedly higher than in the preserum groups. The proportion of Ig-positive cases increased from 41% (preserum) to 73% (postserum). The difference became even more obvious upon analysis of the isotype data, with an increase from 14% to 50% of IgM-positive cases and 19% to 48% of IgG-positive cases in pre- vs. postserum groups (for details see Table 5). Moreover, a statistically significant increase in the level of Ig binding was observed in all three groups (Ig, IgM, and IgG) after serum incubation (Ig, P < 0.001; IgM, P < 0.001; and IgG, P = 0.002) (Fig. 3 and Table 5). This finding implies that mainly nonimmune Igs, present in the malaria-naïve serum, were responsible for the observed Ig binding in the postserum groups, hence resolving the issue of nonimmune vs. specific Igs. Based on postserum data, four subgroups were identified: IgG binders (n = 4, 19%), IgM binders (n = 5, 24%), double-positive isolates binding both IgG and IgM (n = 6; 29%), and Ig-negative isolates (n = 6; 29%).

Fig. 3.

Nonimmune IgG- and IgM-binding profile of fresh Ugandan placental isolates (n = 22) assessed by live SIFA. Each data point represents the Ig-, IgG-, or IgM-binding level of one placental isolate. Each placental isolate was tested directly upon elution from placenta (Pre) and after incubation with malaria naïve serum (Post) by using anti-Ig, -IgG, or -IgM antibodies. ∗, pairwise comparison of Ig-binding level of each isolate before vs. after serum, P < 0.05.

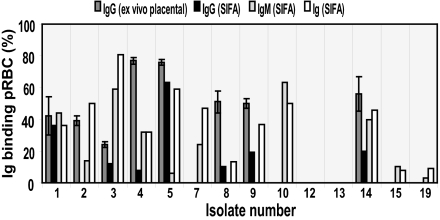

Correlation Between Data Obtained in SIFA vs. ex Vivo Placental Adhesion/Inhibition Assays.

Sixty percent (9 of 15) of the isolates examined by ex vivo placental assays (Fig. 2) were also found to be IgM binders by SIFA (Fig. 4). Moreover, the IgG-binding data on isolates tested in both assays correlated well. In only one instance, the data did not overlap between the assays. Isolate number 2 displayed IgG binding in the ex vivo assay, although the SIFA failed to detect surface-bound IgGs (Fig. 4). This finding can be explained by the nature of the techniques used; SIFA is a more specific and less sensitive experimental approach. The use of monoclonal antibodies provides a highly specific setup; however, fading of fluorescence limits the sensitivity of the assay (specificity = 1; sensitivity = 0.88). This difference can also explain the general tendency toward a lower IgG-binding level in SIFA (mean = 24%; range = 8–63%) vs. the ex vivo placental adhesion/inhibition assay (mean = 52%; range = 24–77%).

Fig. 4.

Ig-binding profile of fresh placental isolates. Correlation between data obtained with two different assays, ex vivo placental adhesion/inhibition (IgG) and live SIFA (Ig, IgM, and IgG).

Discussion

During pregnancy, a new organ, the placenta, is introduced to the body. A subpopulation of P. falciparum parasites are thus endowed with a new niche for growth and sequestration. Exploiting in vitro-propagated isolates as models for parasites implicated in placental malaria, we have herein demonstrated a link between CSA- and Ig-binding phenotypes. We found that not only IgM but IgG binds to the surface of CSA-selected parasites and that a var2CSA-encoded PfEMP1, shown to mediate CSA binding in CSA-selected parasites, also encompasses IgG- and IgM-binding domains. We in addition demonstrate that binding to nonimmune human IgG and IgM constitutes a recurrent phenotype in vivo and that binding to several receptors (CSA/HA/IgG/IgM) rather than a single one is a characteristic of fresh placental isolates.

An explanation for the observed linkage between CSA- and Ig-binding phenotypes in vitro is perhaps the involvement of the same ligand in both interactions. This explanation is supported by our finding of IgG- and IgM-binding domains in 3D7VAR2CSA. In fact, the same domains previously identified to mediate CSA binding (12), DBL2-X and DBL6-ε, displayed IgG and IgM binding as well. IgM was, in addition, found to bind the DBL5-ε domain, suggesting that overlapping but somewhat different binding sites/motifs interact with IgG and IgM. Semblat et al. (20) reported recently that only var2CSA DBL6-ε interacts with IgM. But the authors investigated var2CSA domains from a different parasite line (FCR3). Although var2CSA alleles are unusually conserved for being var genes, sequence heterogeneity is high between different isolates as compared with the rest of the genome (21). In addition, the use of a different cell expression system with low transfection-efficiency rates and the background problems described by Semblat et al. (20) perhaps affected the sensitivity of the experimental setup.

A correlation between CSA and IgM binding has been reported in in vitro-adapted parasites panned on CSA (17). The investigators failed, however, to detect IgG binding. This discrepancy probably reflects differences in the sensitivity of Ig detection and differences in experimental setups (Fig. 5). By using two different techniques, SIFA and ex vivo placental adhesion/inhibition assay, we here demonstrate that IgG is indeed involved in the placental adhesion of fresh Ugandan placental isolates. This work describes nonimmune IgM binding in fresh placental isolates. Together, these observations and the previous findings by Flick et al. (16) support a role for nonimmune Igs in the placental sequestration of parasites.

Alongside interactions with nonimmune Igs, the majority of Ugandan isolates bound CSA and HA, endorsing previous observations on the involvement of the two receptors. Fried et al. (22) recently investigated adhesion of Tanzanian placental isolates to CSA, HA, and IgG. They concluded that CSA is the major receptor. Our findings suggest that multiadhesive placental isolates do exist (see Supporting Discussion in Supporting Text), in line with a previous report by Beeson et al. (15) on the cobinding of clinical placental isolates to CSA and HA. Beeson and colleagues did not, however, assess the role of immunoglobulins. Observed multiadhesiveness can be explained by both the presence of separate pRBC subpopulations with different receptor specificities or/and a single subpopulation interacting with all receptors. Our ex vivo placental adhesion/inhibition data indicate that most isolates consisted of pRBC populations with overlapping receptor specificities (Fig. 2). Such dynamics would have been overlooked had we assessed binding using receptor preparations coated on plastic. The latter is a commonly exploited approach that selects for the receptor-binding subpopulation of interest without providing insight on the relative involvement of other receptor-binding pRBC populations in the isolate. The use of normal placental cryosections provided us with a more authentic experimental setting, in that a plethora of placental receptors are present in a native and thus structurally relevant form. However, it has to be borne in mind that the receptor expression level and usage can differ in uninfected and infected placentae because of inflammatory responses and pathological changes.

Both CSA and HA have been shown to interact predominantly with parasites of placental origin. IgM binding has mainly been described as a phenotype of rosetting P. falciparum isolates, a common feature of isolates from children with severe malaria (23). Rosetting has, however, rarely been observed in P. falciparum isolates from pregnant women (24). Accordingly, we did not observe rosetting in any of the in vitro-adapted or fresh isolates. It is thus possible that IgM has a different role in placental isolates. The large pentameric IgM molecules bound to the pRBC surface may enhance the placental pRBC sequestration through interactions with other receptors, such as CSA or Fc receptors. The presence of Fcμ receptors in the placenta is, however, still elusive. But, as opposed to IgM, several IgG-binding receptors are known to be expressed in the placenta (FcRn, annexin II, and placental alkaline phosphatase) (25). Whereas very little IgG is present in the villous stroma of placentas at 8–10 weeks gestation, there is a significant rise in the maternal IgG transfer to the fetus from the second trimester and onwards (25). The second trimester is also the time when the placenta undergoes a series of morphological changes coinciding with the peak of placental malaria in endemic areas (3, 26).

In years past, CSA and CSA-binding ligands have been the main focus of researchers within the pregnancy malaria field. Current thinking is that identification of a previously uncharacterized CSA-binding ligand responsible for placental adhesion would be the prime vaccine candidate for PAM. As we have demonstrated here, a role for other placental receptors cannot be excluded. We have also demonstrated that var2CSA-encoded domains alongside CSA binding can support interactions with nonimmune Igs. Var2csa was also recently suggested to be associated with the HA-adhesion phenotype of some parasite clones (27). However, whether the same ligand is involved in all of the binding events observed in fresh placental isolates remains to be elucidated. Moreover, based on existing data, it is uncertain how many different PfEMP1 variants or perhaps other unidentified ligands need to be recognized by the host's immune system before an optimal protective immune response against placental isolates develops. In light of the data presented here, the future success of any antiadhesion intervention in placental malaria necessitates an in-depth understanding of these alternative receptor–ligand interactions adopted by the parasite.

Methods

For details on P. falciparum culture, CSA selection, CSA adhesion, sex-specific serum recognition, and statistical analyses, see Supporting Methods in Supporting Text.

Surface Immunofluorescence.

All assays were performed on unfixed mature pigmented trophozoite-stage parasite cultures (25–30 h after invasion). Each parasite line was tested with the following reagents: FITC-conjugated sheep anti-human Ig (final concentration 40 μg/ml; SBL Vaccines, Stockholm, Sweden) (28), mouse mAbs to human IgG-Fc (clone MK1A6; Serotec, Hornby, ON, Canada), IgM (clone M15/8; Serotec), and matched isotype control (clone W3/25; Serotec). The mouse mAbs were all of the IgG1 class and were used at a final concentration of 20 μg/ml. Optimal working dilutions of the antibodies were assessed in titration assays (0.1–20 μg/ml) with the Ig-binding parasite TM284S2 (Fig. 5). Aliquots of each culture suspension with a parasitemia of 5–10% and a hematocrit of 5% were washed twice in RPMI medium 1640. The cells were incubated with the reagents in a volume of 100 μl for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Cells labeled with mAbs to hIgG/IgM were further incubated with highly cross-absorbed Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:800; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 45 min at RT (further details are in Supporting Methods). Basically, the same procedure was used on the Ugandan isolates. These isolates, however, were tested both directly upon elution from the placenta (see below) and after 1 h of incubation with 50% malaria-naïve serum (blood group AB Rh+) at 37°C.

3D7VAR2CSA Transfectants and Ig Binding.

The six domains of 3D7 PFL0030c var2CSA (GenBank accession no. NP_701371) were amplified from genomic DNA by PCR and cloned into the pSRα5–12CA5 vector (Affymax Research Institute, Palo Alto, CA) as described (12). Chinese hamster ovary PgsA-745 (CHO-745) cells deficient in glycosaminoglycans (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were transfected with these plasmids, and stable transfectants expressing the various domains were used for Ig-binding assays. Cells were washed in PBS and preblocked in 1% BSA for 45 min at RT. In each experimental run, the six transfectants expressing the various 3D7VAR2CSA domains and the CHO-745 untransfected cells were incubated with biotin-labeled human IgG or IgM (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) at a final concentration of 0.1 mg/ml. The domain expression level of each transfectant was monitored during each run by using a monoclonal biotin-labeled anti-hemagglutinin antibody (1:100; Roche, Indianapolis, IN) targeting an N-terminal tag of the surface-expressed proteins. In each reaction, 2 × 105 cells were incubated with the various reagents for 1 h at RT. After three washes in PBS, the cells were incubated with allophycocyanin-labeled streptavidin (APC-SA) (1:10; BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) for 30 min on ice in the dark. Each transfectant was also tested for background binding to APC-SA. After the final three washes in PBS, cells from each reaction were resuspended in 200 μl of PBS and directly analyzed on a FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). At least 20,000–30,000 viable cells were analyzed per sample. The CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) was used for data analysis. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

Ugandan Study Population.

A total of 24 women with active P. falciparum placental infection were included in this study. These subjects were part of a cross-sectional investigation on malaria infection in pregnancy at Mulago Hospital, Uganda's National Referral Hospital in Kampala. Full informed consent (or assent for those <18 years of age) was obtained from all of the participants. Pregnancy history, socioeconomic indicators, clinical examination report, and pregnancy outcome were recorded by using a standardized questionnaire (details in Supporting Methods).

Placenta Collection and pRBC Elution.

Immediately after delivery, the placentas were collected in 0.9% NaCl. A small incision was made on the maternal-facing side, and blood films were prepared for P. falciparum diagnosis. For harvest of pRBCs, several biopsies (3 × 3 cm) were cut off-center from the maternal side of the placenta. After thorough external rinsing with saline solution, the biopsies were repeatedly injected with PBS at several sites to remove excess nonsequestered cells (29). The biopsies were then placed in 50-ml tubes containing PBS with 50 mM EDTA and incubated for 60 min on a tube roller at RT to elute sequestered pRBCs (30, 31). The medium containing pRBCs and blood cells was separated from the placental tissue and centrifuged. The pellet was washed three times in PBS (pH 7.4). To separate the pRBC population from leukocytes and other cells, a suspension of the eluted material was overlaid on 5-ml polymorphprep (Axis-shield, Oslo, Norway) and centrifuged for 20–30 min at 500 × g. The RBC fraction sediments in the very bottom. This fraction was carefully collected and washed three times in PBS. The level of parasitemia of the samples was assessed by using acridine orange vital staining. Any sample with an eluted parasitemia of >2% was used directly in live SIFA (see above) and an ex vivo placental adhesion/inhibition assay.

Ex Vivo Placental Adhesion/Inhibition Assay.

IgG-, CSA-, and HA-binding properties of fresh placental isolates were assessed by using a modified version of a previously described method with unfixed cryosections of fresh human placenta (16, 31). Serial 5-μm cryosections were cut from biopsies originating from one full-term Swedish placenta. Freshly eluted packed RBCs from each placental isolate were resuspended in binding medium (pH 6.8) to obtain a hematocrit of 10%. A volume of 50 μl of this suspension was added to each well containing a placental section (positive control). Involvement of CSA and IgG was assessed by incubating the pRBCs in binding medium containing saturating concentrations of bovine CSA (100 μg/ml; Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) or pure human IgG (5 mg/ml; Biovitrum, Stockholm, Sweden) for 1 h at 37°C before placental adhesion. These soluble molecules compete with IgG and CSA present in the placental section for the binding sites on pRBCs. Involvement of HA was assessed by enzymatic removal (Streptomyces HAase, 25 units/ml; Fluka) of the receptor subset from the placental section before pRBC adhesion (for validation see Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Most isolates were also tested for placental adhesion in the presence of a combination of CSA and IgG with or without the enzymatic removal of HA. PBS was used for all washing steps. Sections were fixed in methanol and stained with 5% Giemsa. Each isolate was also tested for adhesion in the presence of 1 mg/ml BSA. For each placental section, parasites (pRBCs bound to syncytiotrophoblast surfaces and in intervillous spaces) in at least 30 randomly selected high-power fields were counted (magnification, ×400). Placental adhesion in the positive controls is expressed as number of pRBCs bound per mm2. The level of adhesion or inhibition in adhesion after treatment (IgG, CSA, and HAase) is expressed as the percentage of the positive control. Cut-off was set to the MIL obtained with the BSA controls +2 SD. Further details are outlined in Supporting Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the pregnant women who participated in this study. We also thank the laboratory/hospital staff at the labor unit, the Department of Pathology, and the members of the Department of Biochemistry at Mulago Hospital for their technical assistance and give special thanks to Dr. S. Balyejjusa, S. Nanyonga, P. Kakeeto, and J. P. Mpindi. We give many thanks to Drs. B. Gamain and A. Scherf at Institut Pasteur, France, for providing the CHO-transfectant cells. This work was supported by grants from BioMalPar (LSHP-CT-2004-503578), the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA-SAREC), the Swedish Research Council, and the foundation of Erik and Edith Fernström.

Abbreviations

- CSA

chondroitin sulfate A

- HA

hyaluronic acid

- HAase

hyaluronate lyase

- MIL

mean inhibition level

- PAM

pregnancy-associated malaria

- pRBC

parasitized RBC

- RT

room temperature

- SIFA

surface immunofluorescence assay.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Steketee RW, Nahlen BL, Parise ME, Menendez C. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64:28–35. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rasti N, Wahlgren M, Chen Q. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;41:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brabin BJ. Bull WHO. 1983;61:1005–1076. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shulman CE, Marshall T, Dorman EK, Bulmer JN, Cutts F, Peshu N, Marsh K. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:770–778. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fried M, Duffy PE. Science. 1996;272:1502–1504. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5267.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duffy PE, Fried M. Infect Immun. 2003;71:6620–6623. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6620-6623.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Staalsoe T, Shulman CE, Bulmer JN, Kawuondo K, Marsh K, Hviid L. Lancet. 2004;363:283–289. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15386-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Q, Heddini A, Barragan A, Fernandez V, Pearce SF, Wahlgren M. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baruch DI, Pasloske BL, Singh HB, Bi X, Ma XC, Feldman M, Taraschi TF, Howard RJ. Cell. 1995;82:77–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuikue Ndam NG, Fievet N, Bertin G, Cottrell G, Gaye A, Deloron P. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:2001–2009. doi: 10.1086/425521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salanti A, Staalsoe T, Lavstsen T, Jensen AT, Sowa MP, Arnot DE, Hviid L, Theander TG. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:179–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gamain B, Trimnell AR, Scheidig C, Scherf A, Miller LH, Smith JD. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1010–1013. doi: 10.1086/428137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viebig NK, Gamain B, Scheidig C, Lepolard C, Przyborski J, Lanzer M, Gysin J, Scherf A. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:775–781. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salanti A, Dahlback M, Turner L, Nielsen MA, Barfod L, Magistrado P, Jensen AT, Lavstsen T, Ofori MF, Marsh K, et al. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1197–1203. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beeson J, Rogerson S, Cooke B, Reeder J, Molyneux M, Brown G. Nat Med. 2000;6:86–90. doi: 10.1038/71582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flick K, Scholander C, Chen Q, Fernandez V, Pouvelle B, Gysin J, Wahlgren M. Science. 2001;293:2098–2100. doi: 10.1126/science.1062891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Creasey AM, Staalsoe T, Raza A, Arnot DE, Rowe JA. Infect Immun. 2003;71:4767–4771. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4767-4771.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heddini A, Pettersson F, Kai O, Shafi J, Obiero J, Chen Q, Barragan A, Wahlgren M, Marsh K. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5849–5856. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5849-5856.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ricke CH, Staalsoe T, Koram K, Akanmori BD, Riley EM, Theander TG, Hviid L. J Immunol. 2000;165:3309–3316. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Semblat JP, Raza A, Kyes SA, Rowe JA. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2006;146:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trimnell AR, Kraemer SM, Mukherjee S, Phippard DJ, Janes JH, Flamoe E, Su XZ, Awadalla P, Smith JD. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2006;148:169–180. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fried M, Domingo GJ, Gowda CD, Mutabingwa TK, Duffy PE. Exp Parasitol. 2006;113:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowe JA, Shafi J, Kai OK, Marsh K, Raza A. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:692–699. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogerson SJ, Beeson JG, Mhango CG, Dzinjalamala FK, Molyneux ME. Infect Immun. 2000;68:391–393. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.391-393.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simister NE. Vaccine. 2003;21:3365–3369. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garham PCC. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1938;32:13–35. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duffy MF, Byrne TJ, Elliott SR, Wilson DW, Rogerson SJ, Beeson JG, Noviyanti R, Brown GV. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:774–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scholander C, Treutiger CJ, Hultenby K, Wahlgren M. Nat Med. 1996;2:204–208. doi: 10.1038/nm0296-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gysin J, Pouvelle B, Fievet N, Scherf A, Lepolard C. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6596–6602. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6596-6602.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beeson J, Brown G, Molyneux M, Mhango C, Dzinjalamala F, Rogerson S. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:464–472. doi: 10.1086/314899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ljungström I, Perlmann H, Schichtherle M, Scherf A, Wahlgren M. Methods in Malaria Research. Manassas, VA: MR4/ATCC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.