SYNOPSIS

Objectives

We sought to describe the dominant social contexts and meanings of smoking among Mexican university students.

Methods

Structured observations were made and individual in-depth interviews were conducted with 43 university students who were at five levels of involvement with smoking (i.e., never smoker; ex-smoker; experimenter; regular smoker; frequent smoker). Content analysis of interview transcripts was used to distill the primary settings and themes that students associated with smoking.

Results

Outside their homes and away from the purview of their parents, the environments that students frequented were permissive of smoking, supporting their perceptions of smoking behavior, cigarettes, and the tobacco industry as normal and socially acceptable. Cigarette smoking was a highly social practice, with students practicing simultaneous smoking and cigarette sharing to underscore bonds with others. Moreover, the leisure times and places in which students smoked appeared to bolster their perceptions of cigarettes as offering them pleasurable relaxation and escape from boredom and conflictual social relations. All students believed that smoking was addictive and that second-hand smoke was dangerous to non-smokers. The short-term negative outcomes of smoking appeared more salient to students than either the longer-term health outcomes of smoking or the practices of the tobacco industry.

Conclusions

The meanings and context of smoking were comparable to those found among youth in other parts of the world. Successful tobacco prevention messages and policies to prevent smoking in other youth populations may also succeed among Mexican youth.

Over the last 20 years, multinational tobacco corporations have stepped up their marketing efforts in low- and middle-income countries.1–3 At the same time, youth smoking in many of these countries, including Mexico, is on the rise. For instance, the national prevalence of smoking among Mexican adolescents almost doubled from 1988 to 1998, with the greatest increases found among young women.4 These findings appear to parallel those for university students during this period, when smoking prevalence rose from 28% to 42% among males and from 18% to 36% among females at one Mexican university.5 Without increased prevention efforts, there likely will be an exponential increase in the growing burden of tobacco-attributable mortality in Mexico.6,7

Attention to culturally salient values, expectations, and identity concerns can provide important insights into why smoking appeals to youth.8 A clear understanding of these characteristics should also inform communication strategies to prevent smoking and to promote support for tobacco control policies.9,10 Through qualitative research, this study examined the meanings and social contexts of smoking among Mexican university students in order to assist in the development of tobacco prevention materials and strategies in Mexico.

METHODS

Study participants were 18- to 24-year-old students who attended a public university in a central Mexican state. Institutional review board approval for the study protocol was received from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. The first author recruited and conducted individual, in-depth interviews with students between June and November 2003. Students were recruited from classes taught in four of the six largest academic departments at the university. Lists of students who expressed interest were purposively sampled to obtain interviews from an equal number of males and females at different levels of smoking involvement.

All interviews were audio-taped, transcribed, and entered into the Atlas.ti qualitative data analysis program.11 Both authors designed the analysis plan, which proceeded through five general stages.12 First, the principal author read the interviews, familiarizing himself with their content and developing a coding system to characterize this content. Next, he re-read each interview and applied these codes to narrative segments. The third stage involved data display, in which he developed matrices for each topic, with matrix rows containing relevant narrative segments from each interview. In the fourth stage, he examined data in each matrix to discern the primary concepts and relationships across interviews. This data reduction process involved grouping and condensing similar narrative material in order to identify, describe, and contextualize these concepts and relationships. Finally, both authors interpreted the data in light of the research aims and the relevant literature.

RESULTS

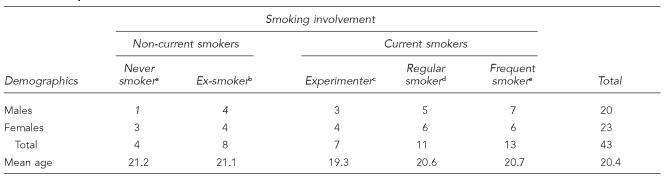

Interviews were completed with 43 of the 51 students who were contacted (84%). Slightly more females (n=23) than males (n=20) were interviewed, and the average age of study participants was 20.4 years. At each of five levels of smoking involvement (see Table for definitions), an approximately equal number of males and females were interviewed, and the mean age of participants was comparable across these levels. Less involved smokers proved the most difficult to locate and recruit, so fewer interviews were conducted with them.

Table.

Participant characteristics

Never smoker=never smoked a cigarette, not even a puff

Ex-smoker=smoked between one and 100 cigarettes in lifetime, but none in previous 30 days

Experimenter=smoked between one and 100 cigarettes in lifetime, one or more of which was in the last 30 days

smoked more than 100 cigarettes in lifetime, and smoked on 20 or fewer of the last 30 days

Frequent smoker=smoked more than 100 cigarettes in lifetime, and smoked on more than 20 of the last 30 days

Primary smoking contexts

The university was the most prominent setting for smoking among students. The campus and its environs provided them with a freedom to smoke that they rarely enjoyed at home, because most students still lived with their parents. There was no coherent tobacco policy on campus, and it was only in classrooms, parts of the library, and offices that smoking was occasionally prohibited. Mostly, students shared cigarettes while talking in the hallways and other rest areas before class, during breaks between classes, and after class. In all campus cafeterias and department buildings except the building that housed the Department of Medicine, cigarette packs and sueltos, or single cigarettes, were sold. Overall, the university setting was extremely permissive of smoking, and students echoed the first author's perception that the vast majority of students smoked.

Most current smokers (21 of 38) also described parties, bars, discos, and cafes as places where they liked to smoke. As at the university, these places generally had no smoking prohibitions. These settings seemed to mark a sustained break from mundane family, work, and school obligations. Generally, students described heavier and more frequent smoking that accompanied the “time-out” of parties, bars, and discos. Intensive smoking was facilitated in the city's popular bar area, for instance, by girls as young as six years old who sold cigarette packs and sueltos while walking amongst bar patrons.

A key feature of these dominant smoking settings was that they were beyond the purview of family members. Indeed, all of the experimenters (7/7) and most of the regular (10/11) and frequent smokers (10/13) did not smoke at home. Although most current smokers had at least one parent who knew that they occasionally smoked (3/6 experimenters; 9/10 regular smokers; 9/13, frequent smokers), only one regular smoker and three frequent smokers had ever smoked in front of their parents. The primary reasons students gave for not smoking in front of parents were that their parents viewed smoking as dangerous or bad (n=6), even leading to other vices (n=1), and because by not smoking in front of their parents they avoided conflict (n=4) and showed respect for them (n=5). Despite their broad reluctance to smoke in front of their parents, students' narratives of smoking a first cigarette appeared more likely to refer to family members who smoked, including siblings and extended family, if they were more involved smokers (1/8 ex-smokers; 0/7 experimenters; 2/11 regular smokers; 6/13 frequent smokers). Hence, even though the vast majority of students did not smoke around their parents, having family members who smoke may be a risk factor for smoking.13

Cigarettes as tokens of reciprocity

When students were asked to talk about their first experience with smoking, many students described smoking as a vehicle for “belonging to,” “being like,” or “feeling part of” a group of friends. Only two people viewed this experience as “pressure” to smoke, while others mainly described these influences as indirect, engendering their curiosity about smoking and providing an opportunity for bonding with friends. For instance, after denying the role of peer pressure, one 18-year-old male frequent smoker described how “two months after starting high school, where everyone was smoking, my curiosity [about smoking] started.” A 22-year-old female experimental smoker also denied feeling peer pressure, instead describing her first shared cigarette as “a kind of socializing that involved us all being equal with one another.” This notion of a shared experiential grounding undergirded other narratives, as well, including a different 18-year-old male frequent smoker's illustration of how peer pressure did not influence his first cigarette: “A friend just bought cigarettes; none of us had smoked before, and without talking about it he just bought them and offered them to us.” Social smoking as a means of bonding and signifying group membership motivated many students to smoke for the first time.

The highly social context of sharing cigarettes with peers was also apparent in both observations and students' descriptions of their current smoking behavior, independent of whether they were male or female. Observations of students in a variety of spaces showed common practices of how, once someone decided to smoke, he or she would either offer a cigarette or a puff of his or her already lit cigarette to the others present. As in descriptions of first smoking experiences, reciprocal sharing of cigarettes underscored the existence of a bond between students. One 18-year-old male experimenter described it this way:

You enter into an environment where everyone's hanging out, and if you smoke, you get more involved in their discussions, in their conversations. It's not that they pay more attention to you, but that you become part of their group, you get more relaxed.

While helping to signify a leisurely break, however temporary, from demands and obligations, sharing cigarettes appeared to affirm and even deepen feelings of group membership.

Smoking to mark transitions and modulate mood

Although leisure was a key feature of the social connotations and context of smoking, the meanings of leisure were often rooted in psychological states that students described, as well. For instance, in their accounts of why they liked smoking, students mostly focused on the relationship between smoking and relaxation (20/29), with all frequent smokers (11/11) mentioning this association. As one 22-year-old female frequent smoker put it:

It's calming. Maybe it's not so much the cigarette or what's inside it, but that…[pause] For me, it's a pause from the stress of my daily life. When you smoke, you're calm, and afterwards you can go back into [daily life] all ready to go.

Other students described similar factors that provoked their desire for the fleeting escape that cigarettes offered them, factors ranging from everyday stresses (n=7), to the heightened stress of exams (n=3) or interpersonal conflict (n=2), to their having a “nervous” or “depressed” personality (n=4). An additional enjoyable feature of smoking was its perceived ability to relieve boredom (n=4). Students perceived these connotations of smoking as empowering them to modulate or control relatively individualized psychological and physiological states. Smoking cigarettes appeared to provide students with a vehicle for temporary relaxation and escape, whether they were withdrawing from an aversive context or emphasizing a leisure-time context.

The desire to feel the physiological sensations that accompanied smoking also turned up in some students' (n=11) descriptions of their motivation for first trying cigarettes as spurred by wanting “to know how smoking felt” and “to experience the effects that smoking provoked.” Most of these students (n=9) viewed this desire as partly resulting from the influences of family members, friends, and advertising. Nevertheless, a higher proportion of frequent smokers (5/13) mentioned this craving for novel sensations than less-involved smokers (0/8 ex-smokers; 2/7 experimenters; 2/11 regular smokers). Such desires among frequent smokers may reflect higher sensation seeking, a psychological trait that presumably increases the drive for seeking out novel, often risky, experiences.14

Why not smoke?

The array of positive social and individual expectations associated with smoking raises questions about why youth would decide to not smoke. The four main dislikes of smoking that ex-smokers raised focused on the bothersome nature of cigarette smoke (4/7), the bad taste of cigarettes (2/7), how they did not experience the relaxing effects touted by smokers (3/7), and their health concerns (2/7). Current smokers identified a similar set of dislikes, with no discernable pattern across sex, age, or extent of smoking involvement. Perhaps due to experience, they further elaborated their dislikes to include how smoke impregnated their clothes (10/29), gave them bad breath (n=4), and gave them yellow fingers and teeth (n=5), while the negative impact of smoking on their health was described both as a potential outcome (n=7) and as something they already sensed, such as shortness of breath (n=5). Only one frequent smoker raised concerns about costs.

When asked to describe one's dislikes about smoking, no student spontaneously mentioned addiction or second-hand smoke. However, when prompted, all students said they viewed smoking as an addictive behavior, with some professing that smoking a single cigarette a day could be a sign of addiction. All students who were asked about second-hand smoke (n=31) said that exposure to it was dangerous. Some students stated that such exposure was at least as dangerous (n=3) or more dangerous (n=9) than smoking itself. Hence, students broadly associated addiction and the dangers of second-hand smoke with cigarettes, but these concerns did not appear salient for them.

Many students (n=23) volunteered a variety of reasons why awareness of health-related outcomes associated with smoking do not affect many youth, including themselves. Nine students at four different levels of smoking involvement described how people do not believe such outcomes would happen to them. Among these students, three experimental smokers, one regular smoker, and one frequent smoker described how they did not smoke enough to cause harm, and the current smoker added that she would quit before it hurt her. Five current non-smokers and four current smokers described a general propensity among youth to ignore, not notice, or not care about things like health consequences. Others described a more specific concern only with the present time (n=2), a lack of concern with the long term (n=2), and the need for youth to experience something to believe it (n=2).

The tobacco industry

No students spontaneously described the influence of tobacco industry marketing in their personal smoking narratives; however, seven of the 36 participants who were directly asked about advertising thought that it influenced their first decision to smoke a cigarette. For instance, one 21-year old male frequent smoker talked of the unconscious influence of tobacco imagery, and how the image of the smoker as a happy, bar-going person who liked dancing matched the image that he had of himself. Aside from focusing on how advertising provided students with stereotypes to which they could aspire or that matched their self-image, the other key theme of advertising influence concerned how it provoked curiosity about smoking. One 18-year-old female ex-smoker typified this perspective when stating: “At the school where I was, students didn't smoke much, but [with the advertising] on the television, in the stores, and all that, you say, ‘Let's try it.’” Despite these allowances, most students denied that tobacco advertising had much of a hold on them.

DISCUSSION

Results from this study illuminate the dominant meanings and contexts of smoking among Mexican university students. Outside of the home and beyond the purview of parents, the places that students frequent appeared extremely permissive of smoking. These environments likely support their perceptions of smoking as a normal, socially acceptable practice. Smoking bans in public places that students frequent may help shift norms against smoking and cigarettes.15,16 The fact that students generally smoke in public places that could be influenced by these bans is noteworthy because youth in some other countries smoke in private spaces that policies cannot effectively regulate.17 Efforts to promote support for smoking bans may be able to capitalize on beliefs about the dangers of second-hand smoke exposure, which were prevalent but not necessarily salient in the study population.

Students' narratives around smoking generally illustrated a process of smoking uptake and progression that was comparable to that found among white and Latino youth in the U.S., with familial, peer, environmental, and even personality factors seeming to play key roles.18–20 Students mostly denied peer influences over their smoking behavior, yet they described highly social interchanges in which simultaneous cigarette smoking and sharing occurred. These findings may reflect selection processes, wherein youth self-select into groups that share similar risk profiles and behaviors, or they may reflect participants' denial of actual peer influences. Studies have provided evidence for the operation of both selection and influence processes on youth smoking behavior.21,22 Adequate determination of the relative impact of selection and influence on smoking among Mexican youth would demand a different study design than used here. Regarding other risk factors, more frequent smokers appeared more likely than less involved smokers to crave the physiological sensations that accompanied smoking. The drive for such stimulation, as well as for the stimulation that accompanies engaging in risky behaviors, has been characterized by the psychological trait of sensation-seeking.14,23 Hence, sensation-seeking may be a risk factor for smoking among Mexican, as well as among U.S. youth.24–26 Finally, it is worth noting that we found no evidence of gender differences around the meanings of, practices related to, or apparent risk factors for smoking. This lack of gender differences may reflect increases in smoking prevalence among young females, since the prevalence among young females is approaching that of their male counterparts.4 Further research is needed to better address any gender differences in Mexico.

Study results suggested that cigarettes served as tokens of reciprocity within social groups of Mexican youth, as has been found among Indian,27 Sri Lankan,17 and Puerto Rican28 youth. The bonding element of social smoking was often accompanied by transitions from one time or space to another, especially a temporary transition to relaxation or involvement in more sustained leisure time (e.g., parties, clubbing). Many youth also reported smoking cigarettes to escape aversive social situations, whether these took place during leisure contexts or not. These associations are also shared with youth in other parts of the world.17,29,30 Although the connotations of relaxation and leisure may be rooted in the biochemistry of nicotine,31 these connotations are reinforced by global tobacco advertising32 and globally distributed mass media.33 Furthermore, marketing efforts around an emerging global youth culture that promotes high stimulation experiences may reinforce ideas about smoking as offering a fleeting escape from boredom,8 as some students in our study believed.

Given prevalent perceptions of these positive smoking outcomes, tobacco prevention messages in Mexico may increase their chances of success if they can re-signify smoking as dissonant with relaxation and escape. A single focus on long-term health outcomes associated with smoking may not be sufficient given students' focus on more proximal concerns and their “unrealistic optimism” about being able to quit.34–38 Apparently more salient concerns about the short-term negative outcomes of smoking (e.g., bad breath, unpleasant odor, yellow teeth) suggest that prevention messages should address these themes, as has been done successfully in some U.S. campaigns.39–41

Another prevention strategy that may counter the positive connotations of smoking could involve highlighting the deceitful practices of the tobacco industry and creating an image of smoking as a behavior that results from industry exploitation.42,43 Although the tobacco industry was a relatively distal entity in students' perceptions of smoking, U.S. youth were similarly reluctant to focus on the tobacco industry before the onset of anti-industry campaigns there.44,45 Moreover, if “sensation-seeking” is a smoking risk factor in Mexico, anti-industry messages may be tailored to appeal to high sensation-seekers.46,47 Because high sensation-seeking youth are at elevated risk for smoking, such messages may have a greater impact on smoking rates than those that mainly appeal to lower risk youth.

This cross-sectional, qualitative study does not provide definitive evidence about the dominant meanings of, risk factors for, or most effective ways to prevent smoking among Mexican youth. Student narratives may have been subject to recall bias, particularly when they described smoking events that took place years before the interview. Moreover, the age and educational status of this population may mean that study results do not apply to other Mexican youth. The study population was selected because of reports about the relatively high prevalence of smoking among university students;5 however, purposive sampling methods likely compromise our ability to generalize results to other university students. Nevertheless, this sampling scheme ensured that interview data were collected from both male and female students with a range of academic interests and with different levels of smoking involvement. The array of perspectives we captured provided a rich source of data for examining how tobacco prevention messages might, or might not, resonate with the values, expectations, and identity concerns of these youth.

Communication campaigns to prevent tobacco use are a key component of comprehensive tobacco control efforts,48 and they can interact synergistically with tobacco control policies, producing a greater impact than either policy or communication campaigns can generate on their own.49 In this regard, communication campaigns may work hand in hand with policies promoted through the World Health Organization's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC),50 which Mexico has ratified. Indeed, communication campaigns may also spur popular support for and extension of policies that the FCTC promulgates.

Although the data reported here were cross-sectional and qualitative, the results suggest that the meanings and contexts of smoking are similar across U.S. and Mexican populations, with familial, peer, environmental, and even personality factors appearing to play key roles in smoking uptake and progression.18–20 As such, it is useful to consider translating successful prevention messages and strategies from the U.S. to Mexico and vice versa. Translation across national boundaries demands careful consideration of how the re-contextualization of materials may transform meanings in ways that compromise their efficacy or that have unintended consequences.51 However, in times of scarce resources, exploration of potential congruencies and similarities across cultural and national contexts may enable more effective transnational collaboration and sharing.52 Global marketing, including global tobacco marketing,53–55 capitalizes on the affinities of expectations, values, and desires among urban youth across the world. Those working against the negative public health consequences of globalization may increase their chances of success by exploring and capitalizing on such affinities, as well.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Christine Jackson, Susan Ennett, Kurt Ribisl, and Deborah Billings for their thoughtful commentary on early drafts of this manuscript. Also, this project was made possible both by the students who graciously shared their experiences and perspectives with us and by the support provided by Mauricio Hernández Ávila, Eduardo Lazcano Ponce, and Raydel Valdés Salgado at the Mexican National Institute of Public Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yach D, Bettcher D. Globalisation of tobacco industry influence and new global responses. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:206–16. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stebbins KR. Going like gangbusters: transnational tobacco companies “making a killing” in South America. Med Anthropol Q. 2001;15:147–70. doi: 10.1525/maq.2001.15.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aguinaga Bialous S, Shatenstein S. Washington: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2002. La rentabilidad a costa de la gente: Actividades de la industria tabacalera para comercializar cigarrillos en América Latina y el Caribe y minar a la salud publica. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campuzano J, Hernández-Avila M, Samet JM, Méndez-Ramirez I, Tapia-Conyer R, Sepúlveda-Amor J. Comportamiento de fumadores en México según las Encuestas Nacionales de Adicciones, 1988-1998. In: Valdés-Salgado R, Lazcano-Ponce EC, Hernández-Avila M, editors. Primer informe sobre el combate al tabaquismo: México ante el Convenio Marco para el Control de Tabaco. Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; 2004. pp. 21–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valdés-Salgado R, Micher JM, Hernández L, Hernández M, Hernández-Avila M. Tendencias del consumo de tabaco entre alumnos de nuevo ingreso a la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1989-1996. Salud Pública de México. 2002;44(Suplemento):S44–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valdés-Salgado R, Lazcano-Ponce EC, Hernández-Avila M. Cuernavaca, México: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; 2004. Primer informe sobre el combate al tabaquismo: Mexico ante el Convenio Marco para el Control de Tabaco. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Smoking-attributable mortality—Mexico, 1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44(19):372–3. 379–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nichter M. Smoking: what does culture have to do with it? Addiction. 2003;98(Supp 1):139–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.9.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine. Washington: National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine; 2002. Speaking of health: assessing health communication strategies for diverse populations. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lupton D. Consumerism, commodity culture and health promotion. Health Promotion Intl. 1994;9:111–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muhr T. 2nd ed. Berlin: Scientific Software Development,; 2004. User's guide for Atlas.ti 5.0. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ulin P, Robinson E, Tolley E. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2004. Qualitative methods in public health. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valdéz-Salgado R, Thrasher JF, Sanchez-Zamorano LM, Lazcano-Ponce E, Reynales-Shigematsu LM, Meneses-González F, et al. Los retos del Convenio Marco para el Control del Tabaco en México: un diagnóstico a partir de la Encuesta sobre Tabaquismo en Jóvenes. Revista de Salud Pública de México. 2006;48(Supp I):S5–S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuckerman M. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum; 1978. Sensation seeking: beyond the optimal level of arousal. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobson PD, Zapawa LM. Clean indoor air restrictions. In: Rabin RL, Sugarman SD, editors. Regulating tobacco. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 207–44. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammond D, Fong GT, Zanna MP, Thrasher JF, Borland R. Tobacco denormalization, anti-industry beliefs, and cessation behavior among smokers from four countries. Am J Prev Med. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.04.004. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehl G, Seimon T, Winch P. Funerals, big matches, and jolly trips: ‘contextual spaces’ of smoking risk for Sri Lankan adolescents. Anthropol Med. 1999;6:337–57. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flay BR, Petraitis J, Hu FB. Psychosocial risk and protective factors for adolescent tobacco use. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(Suppl 1):S59–65. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giovino GA. Epidemiology of tobacco use among U.S. adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(Suppl 1):S31–40. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unger JB, Rohrbach LA, Cruz TB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Howard KA, Palmer PH, et al. Ethnic variation in peer influences on adolescent smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:167–76. doi: 10.1080/14622200110043086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ennett ST, Bauman KE. The contribution of influence and selection to adolescent peer group homogeneity: the case of adolescent cigarette smoking. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:653–63. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Urberg KA, Degirmencioglu SM, Pilgrim C. Close friend and group influence on adolescent cigarette smoking and alcohol use. Dev Psychol. 1997;33:834–44. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanovitzky I. Sensation seeking and adolescent drug use: the mediating roles of association with deviant peers. Health Commun. 2005;17:67–89. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1701_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kopstein AN, Crum RM, Celentano DD, Martin SS. Sensation seeking needs among 8th and 11th graders: characteristics associated with cigarette and marijuana use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;62:195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donohew L, Helm D, Lawrence P, Shatzer M. Sensation seeking, marijuana use and responses to prevention messages: implications for public health campaigns. In: Watson R, editor. Prevention and treatment of drug and alcohol abuse. Clifton (NJ): Humana Press; 1990. pp. 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skara S, Sussman S, Dent CW. Predicting regular cigarette use among continuation high school students. Am J Health Behav. 2001;25:147–56. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.25.2.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nichter M, Nichter M, VanSickle D. Popular perceptions of tobacco products and patterns of use among male college students in India. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:415–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGraw S. University of Connecticut; 1989. Smoking behavior among Puerto Rican adolescents approaches to its study [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pavis S, Cunningham-Burley S, Amos A. Health related behavioural change in context: young people in transition. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:1407–18. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stjerna M-L, Lauritzen SO, Tillgren P. “Social thinking” and cultural images: teenagers' notions of tobacco use. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:573–83. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henningfield J, Pankow J, Garrett B. Ammonia and other chemical base tobacco additives and cigarette nicotine delivery: issues and research needs. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:199–205. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greaves J. London: Scarlet University Press; 1996. Smoke screen: women's smoking and social control. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sargent JD, Tickle JJ, Beach ML, Dalton MA, Ahrens MB, Heatherton TF. Brand appearances in contemporary cinema films and contribution to global marketing of cigarettes. Lancet. 2001;357:29–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03568-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinstein N. Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems. J Behav Med. 1982;5:441–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00845372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinstein N. Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems: conclusions from a community-wide sample. J Behav Med. 1987;10:481–500. doi: 10.1007/BF00846146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weinstein N, Klein WM. Resistance of personal risk perceptions to debiasing interventions. Health Psychol. 1995;14:132–40. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinstein ND. Accuracy of smokers' risk perceptions. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(Suppl 1):S123–30. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinstein ND. What does it mean to understand a risk? Evaluating risk comprehension. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1995;25:15–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flynn BS, Worden JK, Secker-Walker RH. Mass media and school interventions for cigarette smoking prevention: effects two years after completion. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1148–50. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.7.1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flynn BS, Worden JK, Secker-Walker RH, Pirie PL, Badger GJ, Carpenter JH. Long-term responses of higher and lower risk youths to smoking prevention interventions. Prev Med. 1997;26:389–94. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Worden JK, Flynn BS, Geller BM, Chen M, Shelton LG, Secker-Walker RH, et al. Development of a smoking prevention mass media program using diagnostic and formative research. Prev Med. 1988;17:531–58. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(88)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hershey JC, Niederdeppe J, Evans WD, Nonnemaker J, Blahut S, Holden D, et al. The theory of the “truth”: how counter-industry media campaigns effect smoking behavior among teens. Health Psychol. 2005;24:22–31. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evans WD, Price S, Blahut S, Ray S, Herhsey JC, Niederdeppe J. Social imagery, tobacco independence, and the truth campaign. J Health Communication. 2003;9:425–41. doi: 10.1080/1081073049050413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plano Clark VL, Miller DL, Creswell JW, McVea K, McEntarffer R, Harter LM, et al. In conversation: high school students talk to students about tobacco use and prevention strategies. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:1264–83. doi: 10.1177/1049732302238249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quintero G, Davis S. Why do teens smoke? American Indian and Hispanic adolescents' perspectives on functional values and addiction. Med Anthropol Q. 2002;16:439–57. doi: 10.1525/maq.2002.16.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niederdeppe J, Davis KC, Farrelly MC, Yarsevich J. Stylistic features, need for sensation, and confirmed recall of national smoking prevention advertisements. J Communication. 2006 In press. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thrasher JF, Niederdeppe J, Jackson C, Farrelly MC. Using anti-tobacco industry messages to prevent smoking among high-risk youth. Health Educ Res. 2006 doi: 10.1093/her/cyl001. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zaza S, Briss PA, editors. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. The Guide to Community Preventive Services: what works to promote health? [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wakefield M, Chaloupka F. Effectiveness of comprehensive tobacco control programmess in reducing teenage smoking in the USA. Tob Control. 2000;9:177–86. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wipfli H, Stillman F, Tamplin S, da Costa e Silva V, Yach D, Samet J. Achieving the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control's potential by investing in national capacity. Tob Control. 2004;13:433–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Briggs CL. Why nation states and journalists can't teach people to be healthy: Power and pragmatic miscalculation in public discourses on health. Med Anthropol Q. 2003;17:287–321. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wakefield MA, Durrant R, Terry-McElrath Y, Ruel E, Balch GI, Anderson S, et al. Appraisal of anti-smoking advertising by youth at risk for regular smoking: a comparative study in the United States, Australia, and Britain. Tob Control. 2003;12(Supp II):ii82–86. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yach D, Bettcher D. Globalization of tobacco marketing, research and industry influence: perspectives, trends and impacts on human welfare. Development. 1999;42:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saffer H. Tobacco advertising and promotion. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, editors. Tobacco control in developing countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hafez N, Ling PM. How Philip Morris built Marlboro into a global brand for young adults: implications for international tobacco control. Tob Control. 2005;14:262–71. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]