SYNOPSIS

Tobacco use costs approximately $167 billion annually in the U.S., but few tobacco education opportunities are available in schools of public health. Reasons for the discrepancy between the costs of tobacco use and the creation of tobacco training opportunities have not been well explored. Based on the Behavioral Ecological Model, we present 10 recommendations for increasing tobacco training in schools of public health. Six recommendations focus on policy changes within the educational, legislative, and health care systems that influence funds for tobacco training, and four recommendations focus on strategies to mobilize key social groups that can advocate for change in tobacco control education and related policies. In addition, we present a model tobacco control curriculum to equip public health students with the skills needed to advocate for these recommended policy changes. Through concurrent changes in the ecological systems affecting tobacco control training, and through the collaborative action of legislators, the public, the media, and health professionals, tobacco control training can be moved to a higher priority in educational settings.

In 2001, the Association of Schools of Public Health and the American Legacy Foundation created the Scholarship, Training, and Education Program for Tobacco Use Prevention (STEP UP), which awarded $1.8 million to schools of public health to promote tobacco training for public health students.1 While the program funded eight graduate schools of public health to incorporate tobacco control education in their core curricula, no additional monies are available to continue the programs.1 Moreover, of 32 schools of public health in the U.S., 22 report no specific funding for tobacco-related training, and only five report a course exclusively devoted to tobacco.2 In contrast, the U.S. spends $75.5 billion a year on smoking-related health care expenditures (including active smoking and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke) and $92 billion a year on smoking-related productivity losses.3 Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) is estimated to cost $10 billion per year in the U.S.4 Cigarette smoking is the leading preventable cause of death in the U.S., resulting in approximately 1 of 5 deaths each year.5,6 Twenty-two percent of U.S. adults smoke cigarettes.7 Based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001 to 2002, there is no safe level of exposure to ETS, with 43% of nonsmokers with no known source of exposure still having measurable concentrations of serum cotinine.8

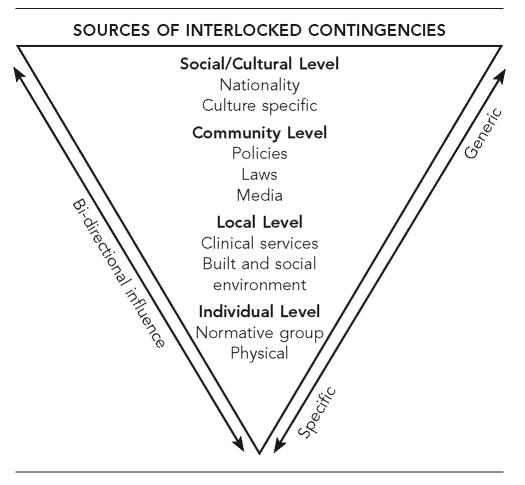

Given the extraordinary costs associated with tobacco use, including smoking and exposure to ETS, it is both necessary and cost effective to identify new funding sources specifically targeted for tobacco control education. We present 10 recommendations based on the Behavioral Ecological Model (BEM) to increase levels of funding for tobacco training.9 As depicted in Figure 1, the BEM proposes that behavior results from the interaction of behavioral influences (social and physical cues, reinforcement, punishment) occurring within and between different ecological levels of society (e.g., schools of public health, health care systems, legislative systems). Some of these behavioral influences pre-exist in our social, health, and legislative systems, while other behavioral influences result from people's social interactions and are ongoing and dynamic. Both the ecological systems/levels influencing behavior and the people interacting with those systems can be targeted to achieve changes in health-related outcomes such as funding for tobacco training. We present six recommendations that target ecological systems that may influence funding for tobacco control education, and four recommendations that target the actions of key social groups that interact within those ecological systems.

Figure 1.

Behavioral Ecological Model

RECOMMENDATIONS TARGETING ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS

Our first six recommendations propose a tobacco training curriculum for schools of public health and target changes in ecological systems that are likely to increase demand for public health training in tobacco control. Public health students who have been trained in the proposed curriculum will be better equipped to carry out the targeted changes in ecological systems.

Recommendation 1: Develop a tobacco control curriculum for schools of public health

Tobacco control competencies have been delineated for medical10–12 and pharmacy students,13 and in a statewide program in Massachusetts.14 The need to articulate the competencies public health professionals should attain in tobacco control has only recently been recognized,1 and a tobacco control curriculum for public health students has not yet been developed. Attaining funding for public health training in tobacco control is likely to be easier if public health tobacco training curricula cover unique skills not already offered in other training programs. Examination of existing curricula or competency guidelines for tobacco education in medical settings suggests that most are based on a medical model emphasizing clinical treatment of disease; none targeted social or policy-level change.10–13 In contrast, the mission of public health is broader, and encompasses activities such as developing community partnerships to solve public health problems, social marketing and communication with the media and community groups, and development of policy-level initiatives to promote public health.15 Thus, tobacco-related competencies for public health professionals extend beyond the competencies for medical professionals and incorporate broader social and policy issues. Since the most significant declines in population levels of tobacco consumption have been observed when changes in social environments—rather than enhanced clinical services—have been the focus of the programs,16 a tobacco-related curriculum based on the public health model has substantial potential to make an independent contribution to national and international tobacco-control efforts. Moreover, skills that could be taught during tobacco training are also linked to fundamental public health competencies that would be useful in other areas of public health intervention.

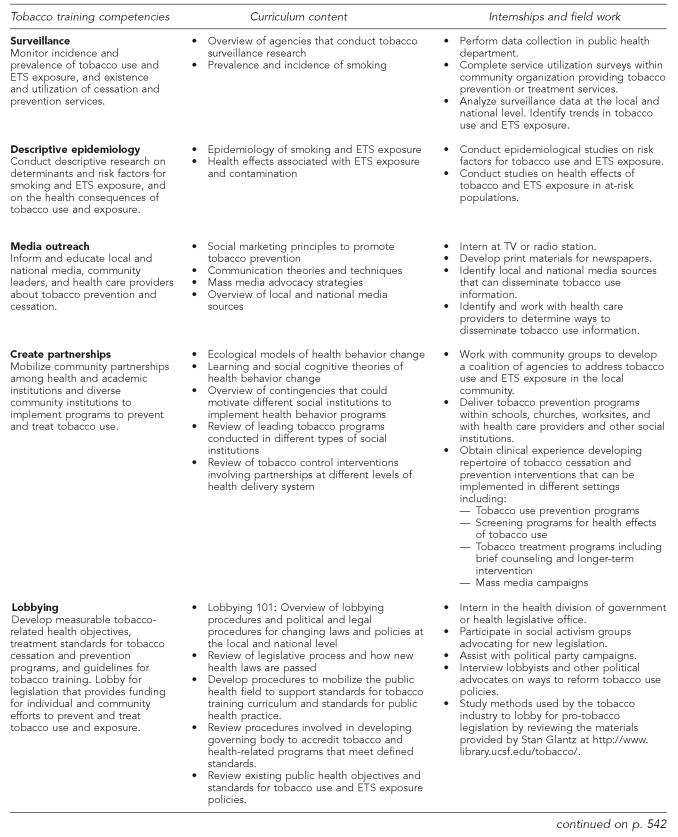

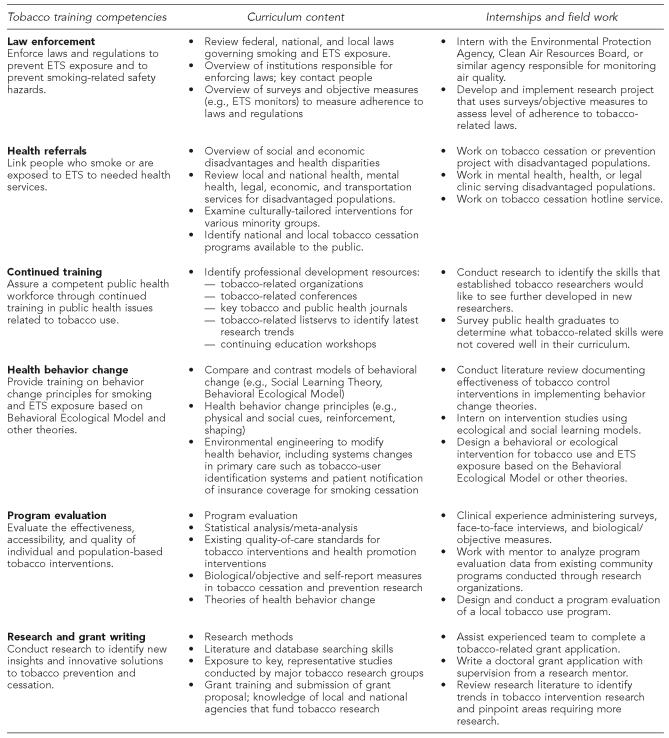

Figure 2 presents a model curriculum for tobacco control education based on the essential services of public health15 and the Behavioral Ecological Model.9 Unlike existing curricula recommended for medical schools,10–13 which emphasize clinical treatment of disease associated with smoking and smoking cessation, the proposed curriculum, designed uniquely for schools of public health, emphasizes social and policy-related changes that could increase public access to tobacco control programs and alter social norms regarding the acceptance of smoking and ETS exposure. While these training guidelines apply specifically to tobacco training within schools of public health, medical, dentistry, and pharmaceutical schools might also benefit from broadening their curricula to recognize that the treatment and prevention of tobacco use and ETS exposure must be addressed at multiple levels. The curriculum includes content traditionally covered in schools of public health, but also suggests new content not traditionally covered extensively such as lobbying, legislative procedures, and media advocacy. To promote the integration of this curriculum into U.S. schools of public health, it could focus not only on tobacco use, but on the top five leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the U.S. A curriculum such as the one outlined in Figure 2 would equip public health professionals with the knowledge and skills to implement the remainder of the recommendations described in this article.

Figure 2.

Tobacco training curriculum based on Essential Public Health Services and Behavioral Ecological Model

a Harrell JA, Baker EL, Essential Services Work Group. The essential services of public health. American Public Health Association [cited 2006 Apr 24]. Available from: URL: http://www.apha.org/ppp/science/10ES.htm

b Hovell MF, Wahlgren DR, Gehrman CA. The Behavioral Ecological Model: integrating public health and behavioral science. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby R, Kegler M, editors. New and emerging models and theories in health promotion and health education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. p. 347-85.

ETS = environmental tobacco smoke

Recommendation 2: Lobby legislators to direct tobacco tax funds to comprehensive tobacco control programs

We propose that legislators allocate at least 20% of tobacco tax funds for tobacco-related control programs. In the early years of the California Tobacco Control Program, 20% of the Proposition 99 tax revenues, which increased the cigarette tax by 25 cents per pack, were allocated to the state's successful tobacco control program.17 Unfortunately, state budgets have now diverted most funds for tobacco control to deficit control.2 Funding for the California tobacco control program has been cut by half; funding for successful programs in Massachusetts, Oregon, Arizona, and Florida have also received deep cuts.16 These funding cuts have been associated with a slower rate of decline in cigarette consumption in recent years; they curtail opportunities for public health specialists to refine existing tobacco control programs and apply tobacco control skills acquired in their training; and they limit opportunities to obtain funding for tobacco training in schools of public health. Moreover, continued declines in funding for tobacco control programs may lead to decreased demand for specialized tobacco training in schools of public health. Public health professionals can do more to lobby their legislators on a regular basis about funds for tobacco training and control, and legislative assistants have suggested that health professionals need to learn more about the legislative process.18

Recommendation 3: Require tobacco control training in schools of public health

Public health professionals should lobby for legislation that makes tobacco training a requirement for public health students. Evidence suggests that most students would like to receive tobacco cessation training;19 however, there is a lack of state laws requiring students in schools of public health to receive or demonstrate competency in tobacco training. To meet diverse training needs while ensuring basic competence among public health students, a stepped care approach could be taken.14 All students should be trained in core public health competencies outlined in Figure 2, and be required to take a course focusing on the five leading causes of morbidity and mortality, one of which is smoking. Students with additional interests in tobacco control could complete additional courses and internships with emphasis on smoking and ETS exposure.

Recommendation 4: Include recommendations for increased tobacco control training on national and international tobacco control agenda

The prevailing tobacco control agenda can play a critical role in informing public policy regarding tobacco control. While increased tobacco training was included as a key recommendation of the Subcommittee on Cessation of the Interagency Committee on Smoking and Health's National Action Plan for Tobacco Cessation20 and in the World Health Organization's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control,21 it was not included as a key program goal or component in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Tobacco Control Program's evidence-based framework for statewide programs to reduce tobacco use.16 Public health students who are trained in the tobacco use curriculum outlined in Figure 2 would be better equipped to take steps to ensure tobacco training is at the forefront of tobacco policy agenda by communicating the importance of training on tobacco-related professional listservs, through local and national pubic health and policy departments, and by presenting and publishing research on the importance of tobacco training.

Recommendation 5: Advocate for health care systems changes related to tobacco use

Systems changes within health care systems may affect the frequency of tobacco-use and ETS counseling. Seventy percent of adult tobacco users see a primary care physician each year, but fewer than 40% are given cessation assistance.22 Moreover, fewer than 5% of adult tobacco users are given advice on reducing their children's and family's exposure to ETS at primary care visits.23

To overcome this deficit, public health students should be trained to implement systems changes associated with increased tobacco counseling in primary care. These include cues and incentives for tobacco counseling such as tobacco-user identification systems, insurance requirements for medical groups to document patient smoking status, and clinician reimbursement.22,24 In addition to systems changes targeting health professionals, systems changes targeting patients may also yield substantial health impacts. One study found that patients who were aware of insurance benefits for smoking cessation were 17% more likely to be offered written cessation materials, 44% more likely to be given a prescription for smoking-cessation medication, and 12% more likely to arrange a return physician visit or phone call, compared to patients not aware of insurance benefits.25 Increased patient awareness of smoking cessation benefits likely increases tobacco cessation inquiries, and cues physician counseling. Currently, 36% of people insured through Medicaid smoke, but only 28% of states that offer Medicaid coverage for smoking cessation treatments inform their beneficiaries of these benefits.26 In California, of 13 licensed HMO's, 69% reported informing members about covered smoking cessation treatments, suggesting room for improvement.27 Related to patient awareness of smoking cessation benefits, there is also a need to increase insurance coverage of smoking cessation treatments. In 2002, only two state Medicaid programs offered coverage for all recommended pharmacotherapy and counseling treatments recommended for tobacco dependence.26 It is important for public health professionals to be trained to advocate for systems changes in health insurance benefits, patient notification of benefits, and routine office practices that increase the likelihood of tobacco counseling.

Recommendation 6: Build a network of professionals interested in tobacco control

Public health professionals interested in tobacco control can benefit from collaborating with diverse academic departments within universities, as well as other organizations involved in tobacco control. By forming a larger, transdisciplinary group of tobacco control specialists, public health professionals can broaden the number of agencies that could potentially fund their research and training activities, extend the range of professional networks within which to lobby for increased funding for tobacco training, increase overall capacity to attain funds by attracting a larger pool of qualified researchers and students who can submit proposals for tobacco-training funds, and increase their visibility as a unique program warranting university and government funding. In addition, transdisciplinary partnerships may enhance the overall quality of tobacco research and training,28 which may further strengthen the likelihood of attaining continued funding for training activities.

RECOMMENDATIONS TARGETING SOCIAL GROUPS

Recommendation 7: Target legislators

To convince legislators to earmark more funds for tobacco prevention and pass laws requiring health professionals to attain basic proficiencies in tobacco control, public health professionals should meet with legislative assistants on a consistent basis. During these meetings, they need to show that there is strong professional and public support for tobacco control, and use real-life examples with supporting statistics to show how tobacco control policies affect patients, the state, or district. While legislators are receptive to obtaining information about tobacco control policies and education, a survey revealed that few physicians lobby legislators about tobacco-related issues.18 Moreover, professional and public demand for tobacco control legislation must be sufficiently strong to outweigh the impact of tobacco industry campaign contributions to U.S. legislators. Between 1993 and 2000, Senate Republicans received an average of $22,004 from the tobacco industry in campaign contributions, while Senate Democrats received an average of $12,956. These differences likely influenced voting behavior on tobacco-related issues; Republicans voted pro-tobacco 73% of the time compared to 23% of the time for Democrats.29 However, even in the face of a strong tobacco industry, tobacco-related legislation in favor of the public's health is possible with persistent lobbying by organized health and social coalitions, along with specific health and economic data supporting the need for tobacco training and prevention.30–32 Efforts by Stan Glantz of the University of California at San Francisco and other organizations have made available to the public millions of legal and research documents concerning health effects, marketing, advertising, and sales of cigarettes (http://www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/). These materials may be studied so that public health professionals can learn to advocate for anti-tobacco legislation using similar strategies that the tobacco industry has successfully used to lobby for pro-tobacco legislation.

Recommendation 8: Target the media

Evidence shows that media coverage shapes the issues that become important in the public mind.33,34 Analysis of media coverage of tobacco indicates that while tobacco is covered frequently, it is often not located as prominently or in as desirable locations in print media.35 Getting the media to attend to the issues considered most important by public health professionals may require media advocacy—the strategic use of news media to advance a social or public policy initiative.34,36 Public health professionals seeking media attention for increased tobacco training are likely to be more successful if they use strategies that match the priorities of local media. These strategies include providing attention-getting local statistics, creating events or “happenings” that local media can cover such as conferences or public demonstrations to promote tobacco training, getting a celebrity or other well known person to attend the event, generating letters to the editor or editorials, using witty or other memorable phrases, and timing events to occur in conjunction with other related newsworthy events.34,37 Framing the story to contain “newsworthy” elements such as controversy, irony, a personal angle, exciting visuals, injustice, or a breakthrough event will also help capture the media's attention.38 The effectiveness of appeals for increased funding for tobacco training might be enhanced by comparing mortality associated with smoking and ETS exposure to deaths due to alcohol, traffic accidents, and obesity—topics that may be more prominent in public awareness.39 Research also suggests that the public's understanding of the risks associated with tobacco use are superficial, indicating that public service announcements that instruct the public more thoroughly in tobacco use risks may be called for.39 If public health professionals can get the issue of tobacco training covered prominently or repeatedly in the media, public awareness about the importance of tobacco training is likely to increase, and may result in increased public pressure for legislators to support greater funding for tobacco training.

Recommendation 9: Target the public

Public health professionals should attempt to increase public support for increased tobacco training through outreach and by emphasizing common public health goals and benefits. Previous successful efforts to pass tobacco-related legislation benefiting the public's health have often involved collaboration among public and professional groups. In the movement to develop smoke-free airlines, which started in 1966 and progressively led to a ban on smoking on all domestic and international fights from the U.S. in 2000, the Association of Flight Attendants’ collaboration with diverse health advocacy groups overcame the power of the tobacco industry.30,31 Similarly, when tobacco advertising in youth-oriented magazines increased after the Master Settlement Agreement that broadly prohibited targeting youth, pressure from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health together with pressure from a national public advocacy organization and the popular press substantially reduced this advertising.40 Public health advocates also successfully collaborated with community-based grassroots organizations and legal teams to enact stringent youth access restrictions to tobacco in Massachusetts.32 By working together, organized labor and public health advocates were more effective than either group would have been working alone.

Multiple strategies can be used to promote successful collaborations among the public and public health professionals to increase funding for tobacco training. In the Massachusetts program to enact youth access restrictions to tobacco,32 public health advocates engaged the public by contacting grassroots organizations and individuals such as parent/teacher organizations, chambers of commerce, Scouts groups, and merchants, and persuading like-minded individuals to attend local public hearings or write letters to express their support for youth tobacco access restrictions. Schools of public health can conduct similar outreach activities to support their tobacco training goals. Having respected public health schools reach out to like-minded individuals may be a powerful strategy for building strong community support for issues such as health system reform to promote tobacco counseling and increased tobacco training for public health professionals.

A second strategy for successfully mobilizing public and professional groups to work together is to have a single, simple message that everyone can agree on and push for in the same direction; this contributed to successful outcomes in the fight for smoke-free airways, tougher youth access restrictions to tobacco, and reductions in youth-oriented tobacco advertising. A third strategy for mobilizing public health and community groups to work together is focusing on how each group can jointly benefit from tobacco-related legislation. For example, a local dog owner's association may care little about tobacco training, but might value being able to walk their dogs in air unpolluted by tobacco smoke. Pointing out that continued “clean air” depends on having sufficient numbers of trained professionals to prevent tobacco use could get both groups working together for a common goal. Increased public health education on the descriptive epidemiology of tobacco use, together with training in building partnerships (Figure 2) will better prepare public health professionals to engage the public in collaborative tobacco control initiatives.

Recommendation 10: Encourage multiple groups to work together toward a common goal of systems change

Tobacco education funding reflects actions taken within multiple, reciprocally interacting ecological systems, including the health care, legislative, and educational systems. As a result, the BEM9 predicts that public health professionals will be most effective in increasing funding for tobacco training and education if they can get multiple groups working together in pursuit of common or interrelated goals. When multiple groups such as the media, national organizations, coalitions, health professionals and researchers, public health agencies, legal groups, and local organizations work together, it is more likely that legislators will take action.41 The voice of many people is likely to be more convincing than the voice of a few. Moreover, tobacco control legislation within one social group or system often sets a precedent that makes it easier for other groups to lobby for change in tobacco policy.

CONCLUSIONS

While the gap between funding for tobacco training and the economic costs of tobacco use and ETS exposure is large, policy changes within educational, legislative, and health care systems have tremendous potential to bridge this gap. As part of California's tobacco control program, policy changes within multiple ecological contexts involving the influence of legislators, the public, media, and health professionals resulted in a 25% decline in smoking prevalence in California over a 12-year period,42 and led to substantial changes in social norms regarding the acceptability of smoking in California, relative to the rest of the U.S.43 By improving public health training in tobacco control in schools of public health, and by working together with the public, media, legislators, and other health groups, public health professionals can move tobacco training to a higher priority in educational settings.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funds from the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program of the University of California (#12FT-0244), and by funds from the Universitywide AIDS Research Program of the University of California (#ID04-SDSU-060).

REFERENCES

- 1.Balas AE, Ramiah K, Martin K. ASPH/American Legacy Foundation STEP UP Program: an innovative partnership for tobacco studies in the schools of public health. Pub Health Reports. 2004;119:380–5. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weist E, Ramiah K. STEP UP to tobacco control: advancing the role of public health and public health professionals' workshop. Final proceedings; 2004 Apr 14–16; St. Louis, MO. 2004. Aug 6, [cited 2006 May 15]. Also available from: URL: http://www.asph.org/UserFiles/Main%2021.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses—United States, 1997–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(25):625–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behan DF, Eriksen MP, Lin Y. 2005 Economic effects of environmental tobacco smoke. 2005. Mar 31, [cited 2006 Feb 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.soa.org/ccm/content/areas-of-practice/life-insurance/research/economic-effects-of-environmental-tobacco-smoke-SOA/

- 5.Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs—United States, 1995–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(14):300–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Center for Health Statistics (US) Hyattsville (MD): DHHS; 2005. Health, United States, 2005, with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans; p. 178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(20):427–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pirkle JL, Bernert JT, Caudill SP, Sosnoff CS, Pechacek TF. Trends in the exposure of nonsmokers in the U.S. population to secondhand smoke: 1988–2002. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:853–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hovell MF, Wahlgren DR, Gehrman CA. The behavioral ecological model: integrating public health and behavioral science. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby R, Kegler M, editors. New and emerging models and theories in health promotion and health education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 347–85. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferry LH, Grissino LM, Runfola PS. Tobacco dependence curricula in US undergraduate medical education. JAMA. 1999;282:825–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geller AC, Zapka J, Brooks KR, Dube C, Powers CA, Rigotti N, et al. Tobacco control competencies for US medical students. Am J Pub Health. 2005;95:950–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spangler JG, George G, Foley KL, Crandall SJ. Tobacco intervention training: current efforts and gaps in US medical schools. JAMA. 2002;288:1102–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corelli RL, Kroon LA, Chung EP, Sakamoto LM, Gundersen B, Fenlon CM, et al. Statewide evaluation of a tobacco cessation curriculum for pharmacy students. Prev Med. 2005;40:888–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pbert L, Ockene JK, Ewy BM, Leicher ES, Warner D. Development of a state wide tobacco treatment specialist training and certification programme for Massachusetts. Tob Control. 2000;9:372–81. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.4.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrell JA, Baker EL, Essential Services Work Group The essential services of public health. American Public Health Association. [cited 2006 Apr 24]. Available from: URL: http://www.apha.org/ppp/science/10ES.htm.

- 16.Wisotzky M, Albuquerque M, Pechacek TF, Park BZ. The National Tobacco Control Program: focusing on policy to broaden impact. Pub Health Reports. 2004;119:303–10. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sung HY, Hu TW, Ong M, Keeler TE, Sheu ML. A major state tobacco tax increase, the master settlement agreement, and cigarette consumption: the California experience. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1030–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landers SH, Sehgal AR. How do physicians lobby their members of Congress? Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3248–51. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tobacco use and cessation counseling – global health professionals survey pilot study, 10 countries, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(20):505–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiore MC, Croyle RT, Curry SJ, Cutler CM, Davis RM, Gordin C, et al. Preventing 3 million premature deaths and helping 5 million smokers quit: a national action plan for tobacco cessation. Am J Pub Health. 2004;94:205–10. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wipfli H, Stillman F, Tamplin S, da Costa e Silva VL, Yach D, Samet J. Achieving the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control's potential by investing in national capacity. Tob Control. 2004;13:433–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keller PA, Fiore MC, Curry SJ, Orleans CT. Systems change to improve health and health care: lessons from addressing tobacco in managed care. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(Suppl 1):S5–8. doi: 10.1080/14622200500077966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanski SE, Klein JD, Winickoff JP, Auinger P, Weitzman M. Tobacco counseling at well-child and tobacco-influenced illness visits: opportunities for improvement. Pediatrics. 2003;111:E162–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.e162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor CB, Curry SJ. Implementation of evidence-based tobacco use cessation guidelines in managed care organizations. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27:13–21. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2701_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solberg LI, Davidson G, Alesci NL, Boyle RG, Magnan S. Physician smoking-cessation actions: are they dependent on insurance coverage or on patients? Am J Prev Med. 2002;23:160–5. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00493-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.State Medicaid coverage for tobacco-dependence treatments—United States, 1994–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(3):54–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halpin Schauffler H, Mordavsky JK, McMenamin S. Adoption of the AHCPR clinical practice guideline for smoking cessation: a survey of California's HMOs. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:153–61. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nash JM, Collins BN, Loughlin SE, Solbrig M, Harvey R, Krishnan-Sarin S, et al. Training the transdisciplinary scientist: a general framework applied to tobacco use behavior. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(Suppl 1):S41–53. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001625528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luke DA, Krauss M. When there's smoke there's money: tobacco industry campaign contributions and U.S. Congressional voting. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:363–72. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holm AL, Davis RM. Clearing the airways: advocacy and regulation for smoke-free airlines. Tob Control. 2004;13(Suppl 1):i30–6. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.005686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pan J, Barbeau EM, Levenstein C, Balbach ED. Smoke-free airlines and the role of organized labor: a case study. Am J Pub Health. 2005;95:398–404. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.040592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersen BS, Begay ME, Lawson CB. Breaking the alliance: defeating the tobacco industry's allies and enacting youth access restrictions in Massachusetts. Am J Pub Health. 2003;93:1922–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farrelly MC, Davis KC, Haviland ML, Messeri P, Healton CG. Evidence of a dose-response relationship between “truth” antismoking ads and youth smoking prevalence. Am J Pub Health. 2005;95:425–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holder HD, Treno AJ. Media advocacy in community prevention: news as a means to advance policy change. Addiction. 1997;92(Suppl 2):S189–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caburnay CA, Kreuter MW, Luke DA, Logan RA, Jacobsen HA, Reddy VC, et al. The news on health behavior: coverage of diet, activity, and tobacco in local newspapers. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30:709–22. doi: 10.1177/1090198103255456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Durrant R, Wakefield M, McLeod K, Clegg-Smith K, Chapman S. Tobacco in the news: an analysis of newspaper coverage of tobacco issues in Australia, 2001. Tob Control. 2003;12(Suppl 2):ii75–81. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Advocacy Institute. Smoke signals. The tobacco control media handbook. [cited 2006 Apr 24]. Available from: URL: http://www.strategyguides.globalink.org/guide10.htm.

- 38.Dorfman L. Blowing away the smoke. Framing for access: how to get the media's attention. Advisory No. 5. [cited 2006 Apr 24]. Available from: http://www.strategyguides.globalink.org/guide06.htm.

- 39.Biglan A. Reno (NV): Context Press; 1995. Changing cultural practices: a contextualist framework for intervention research; pp. 207–55. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamilton WL, Turner-Bowker DM, Celebucki CC, Connolly GN. Cigarette advertising in magazines: the tobacco industry response to the Master Settlement Agreement and to public pressure. Tob Control. 2001;11(Suppl 2):ii54–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_2.ii54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Freudenberg N. Public health advocacy to change corporate practices: implications for heath education practice and research. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32:298–319. doi: 10.1177/1090198105275044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pierce JP, Gilpin EA, Emery SL, White MM, Rosbrook B, Berry CC, et al. Has the California tobacco control program reduced smoking? JAMA. 1998;280:893–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.10.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilpin EA, Lee L, Pierce JP. Changes in population attitudes about where smoking should not be allowed: California versus the rest of the USA. Tob Control. 2004;13:38–44. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.004739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]