Abstract

Objective To investigate whether funding of drug studies by the pharmaceutical industry is associated with outcomes that are favourable to the funder and whether the methods of trials funded by pharmaceutical companies differ from the methods in trials with other sources of support.

Methods Medline (January 1966 to December 2002) and Embase (January 1980 to December 2002) searches were supplemented with material identified in the references and in the authors' personal files. Data were independently abstracted by three of the authors and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Results 30 studies were included. Research funded by drug companies was less likely to be published than research funded by other sources. Studies sponsored by pharmaceutical companies were more likely to have outcomes favouring the sponsor than were studies with other sponsors (odds ratio 4.05; 95% confidence interval 2.98 to 5.51; 18 comparisons). None of the 13 studies that analysed methods reported that studies funded by industry was of poorer quality.

Conclusion Systematic bias favours products which are made by the company funding the research. Explanations include the selection of an inappropriate comparator to the product being investigated and publication bias.

Introduction

Clinical research sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry affects how doctors practise medicine.1 An increasing number of clinical trials at all stages in a product's life cycle are funded by the pharmaceutical industry,2,3 probably reflecting the fact that the pharmaceutical industry now spends more on medical research than do the National Institutes of Health in the United States.4 Most pharmacoeconomic studies are either done in-house by the drug companies or externally by consultants who are paid for by the company.5,6

Results that are unfavourable to the sponsor—that is, trials that find a drug is less clinically effective or cost effective or less safe than other drugs used to treat the same condition—can pose considerable financial risks to companies. Pressure to show that the drug causes a favourable outcome may result in biases in design, outcome, and reporting of industry sponsored research.7

A recent systematic review of the impact of financial conflicts on biomedical research found that studies financed by industry, although as rigorous as other studies, always found outcomes favourable to the sponsoring company.8 However, this review looked for papers published only in English, excluded reports in letters and abstracts, and looked at studies funded by other industries. We reviewed the relation between the source of funding of the research and the reported outcomes and investigated whether quality of the methods in studies funded by pharmaceutical companies differs from that in other studies.

Methods

Study selection

We included only studies that specifically stated that they analysed research sponsored by a pharmaceutical company, compared methodological quality or outcomes with studies with other sources of funding, and reported the results in quantitative terms. Outcomes of interest were conclusions about differences in drug effectiveness, adverse effects, cost outcomes, or publication status between industry funded trials and other trials. Work published in any language was eligible for inclusion.

Some studies analysed both pharmacological and non-pharmacological trials and combined research funded by drug companies and other industries into one group. In these cases, if most were non-pharmaceutical trials and were funded by other industries they were excluded.

Search strategy

We searched Medline from January 1966 to December 2002 using a combination of terms as both MESH subject headings (exploded) and key words (“clinical trials,” “conflict of interest,” “drug industry,” “financial support,” “publication bias” (subject heading only), “research design,” and “research support.”) We searched Embase from January 1980 to December 2002 using a combination of terms as subject headings (exploded) and key words (“clinical trials” (subject heading only), “drug industry,” “ethics,” “financial management,” “methodology,” and “ethics.” To find more studies, we scanned the reference lists from each of the articles and searched the Cochrane methodology register. We placed messages on two email drug discussion groups, contacted content experts, and searched our personal libraries. In cases where the reported results were incomplete, we contacted the lead author and asked for further details. A single author (JL) did the initial selection of studies and sent copies of each of these studies to the other three authors for validation of the inclusion criteria.

Data collection

From each study, we extracted the study design, type of research assessed in the study, design of research assessed in the study, search strategy used to locate research, time period covered, drug or drug class, disease, number of industry and non-industry funded articles analysed in each study, how industry funding was defined, criteria used to assess methodological quality of the research, results with respect to methodological quality or outcome of the research, and primary purpose of study.

We provide a critical description of each included study, but do not assess methodological quality (see table 1). Since our included studies had a variety of designs—that is, cohort collections of trials, meta-analyses, and economic studies—and since we included letters and abstracts with limited descriptions of methods, we had no valid and reliable quality assessment instrument available for assessing their methodological quality. We did not use a component approach to assess their quality since this approach applies to randomised controlled trials.9,10

Table 1.

General characteristics of studies

| Study (first author) | Type of publication | Research assessed | Design of research | Search strategy used to find research | Time covered | Number of separate trials funded by industry | Number of separate trials not funded by industry | How was industry funding defined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azimi et al12 | Journal article, systematic review | Pharmacoeconomic studies | Cost effectiveness | Abridged Index Medicus | 1 January 1990 to 30 June 1996 | 10 | 34 | Explicit acknowledgment of support from private industry in article |

| Chard et al13 | Journal article, systematic review | Clinical trials | Prospective experimental, retrospective or prospective cohort studies, general disease reviews/specific intervention reviews, studies reporting pooled data | BIDS Institute for Scientific Information, Cochrane Library, Embase, Medline | 1950 to March 1998 | 114 with pharmaceutical sponsorship out of 128 with commercial sponsorship | 802 | Source of funding declared in published article |

| Cho et al14 | Journal article, systematic review | Clinical trials | Experimental (randomised and non-randomised), observational | Computer generated list of random numbers from 625 symposiums, symposiums' articles matched to article from parent journal | Not stated | For quality score 50; for outcome 40 | For quality score 77; for outcome: 112 | Article acknowledged drug company providing funding or drugs or any authors employed by drug company |

| Clifford et al15 | Journal article, review | Clinical trials | Randomised controlled | Manual search for randomised trials in 5 general medical journals (convenience sample of 100 trials; 20/journal) | January 1999 to October 2000 | 44 by company only; 22 by company and at least 1 not for profit source | 28 | Acknowledged grant support; drug company employee listed as author; drug supplied by company; other types of company support |

| Davidson16 | Journal article, review | Clinical trials | Concurrent or crossover control group, before and after | Search of 5 major general medicine journals | 1984 | 37 | 70 | Acknowledgments stated support from company (excluding supply of drug or placebo) or any authors worked for company |

| Dickersin et al17 | Journal article, cohort study | Clinical trials | Observational, clinical trial, other | Manual search Institutional Review Board logs for studies receiving approval at one university | Studies approved in 1980 or before 1980 and still ongoing | 42 | 472 | Not stated |

| Dieppe et al18 | Journal letter, review | Meta-analyses | Meta-analysis | Search for meta-analyses in 8 high-impact journals | 1993 to 1997 | 18 | 117 | Not stated |

| Djulbegovic et al*19 | Abstract, systematic review | Clinical trials | Randomised controlled | From list of trials maintained by American Society of Hematology | 1980 to 2000 | 23 | 7 | Source of funding obtained from paper or investigator; association with manufacturer if drug supplied or grant support |

| Djulbegovic et al*20 | Journal article | Clinical trials | Randomised controlled | Cochrane search strategy | 1996 to 1998 | 35 | 101 | Source of funding obtained from paper or investigator; association with manufacturer if drug supplied or grant support |

| Easterbrook et al21 | Journal article, retrospective cohort study | Clinical trials | Observational, experimental (clinical and non-clinical) | Manual search ethics committee records at 1 university | 1 January 1984 to 31 December 1987 | 108 | 177 | Direct contact with investigator or co-investigator |

| Freemantle et al22 | Journal article, systematic review | Clinical trials | Randomised controlled | Embase, Medline, reviewed reference lists, contacted authors | 1982 to 1997 | Not stated | Not stated (total 105 trials) | Not stated |

| Freidberg et al23 | Journal article, systematic review | Pharmacoeconomic studies | Cost minimisation, cost identification, cost effectiveness | HealthStar, Medline | 1988 to 1998 | 20 | 24 | Statement in article or by contacting investigator if no statement |

| Ioannidis24 | Journal article, retrospective cohort study | Clinical trials | Randomised | Trials conducted under auspices of two AIDS trial groups | 1986 to 1996 | 11 | 98 | Not stated |

| Jadad et al25 | Journal article, systematic review | Systematic reviews, meta-analyses | Systematic review, meta-analysis | CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, HealthStar, Medline, personal collections, reference lists | 1988 to 1998 | 6 | 44 | Not stated |

| Kamal-Bahl et al26 | Journal article, systematic review | Pharmacoeconomic studies | Cost effectiveness, cost benefit, incremental cost analysis | HealthStar, Medline, contacted experts, reference lists, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database, National Institute for Clinical Excellence, Canadian Coordinating Office of Health Technology Assessment | 1 January 1990 to 31 August 2001 | 4 | 8 | Not stated |

| Kemmeren et al27 | Journal article, meta-analysis | Clinical trials | Cohort, case-control | Medline, contacted experts, reference lists | October 1995 to December 2000 | 4 | 5 | Industry funding explicitly stated in acknowledgement |

| Kjaergard et al28 | Journal article, retrospective cohort study | Clinical trials | Randomised controlled and quasi-randomised controlled | Handsearch of Hepatology, Medline | January 1981 to August 1998 | Not stated | Not stated (total 235) | Not stated |

| Knox et al†29 | Journal article, systematic review | Pharmacoeconomic studies | Cost minimisation, cost identification, cost effectiveness | HealthStar, Medline | 1988 to 1998 | 20 | 24 | Statement in article or by contacting investigator if no statement |

| Koepp et al30 | Journal letter, comment on meta-analysis | Clinical trials | Not stated | Studies were reported in previously published meta-analysis | Not stated | 8 | 5 | Authors employed by manufacturer, received grants, held stocks or options, in-house research of methodological or statistical analysis provided by manufacturer |

| Liebeskind et al*31 | Abstract, systematic review | Clinical trials | Randomised controlled | Medline search, international trial registries | 1957 to 1997 | Not stated | Not stated (total 127) | Not stated but review discriminated between corporate sponsorship and corporate provision of drug |

| Mandelkern32 | Journal letter, review | Clinical trials | Not stated | Manual review of one year of regular issues of Journal of Clinical Psychiatry | 1997 | 16 | 16 | Stated at front of article |

| Massie et al§33 | Journal letter, review | Clinical trials | Not stated | Articles published over 3 year period in 8 major journals | 1980 to 1982 | 59 | 23 | From article and by direct contact with authors |

| Neuman et al34 | Journal article, systematic review | Pharmacoeconomic studies | Cost effectiveness | Medline, HealthStar, CancerLit | 1975 to 1997 | cost effectiveness 77; quality 32§ | cost effectiveness 538; quality 118§ | Not stated |

| Rochon et al*35 | Journal article, systematic review | Clinical trials | Randomised controlled | Medline search of 3 journals | January 1990 to November 1992 | 142 by company only; 25 both company and government/foundation | 16 government/foundation; 59 no source | Acknowledged grant support; drug company employee listed as author; drug supplied by company; other types of company support |

| Sacristan et al*36 | Journal letter, review | Pharmacoeconomic studies | Cost effectiveness | Medline search in 6 general medical journals; hand search of Pharmacoeconomics | Medline: 1988 to 1994; Pharmacoeconomics 1993 to 1994 | General medical journals 6; Pharmacoeconomics 18 | General medical journals 63; Pharmacoecomonics 6 | Not stated |

| Stern et al*37 | Journal article, retrospective cohort study | clinical trials | Randomised controlled, concurrent and historical controlled, uncontrolled | Search ethics committee submissions at 1 hospital | September 1979 to December 1988 | Not stated | Not stated | Stated in submission to ethics committee |

| Thomas et al38 | Journal letter, systematic review | Clinical trials | Original research | Medline | 1966 to 2001 | 48 (30 by company A; 18 by company B) | 22 | Funded by company; author was company employee; correspondence address used company address; statistical analysis done by company |

| Vandenbroucke et al39 | Journal letter, review | Clinical trials | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | 4 | 9 | Not stated |

| Wahlbeck et al40 | Journal letter, comment on systematic review | Clinical trials | Not stated | Cochrane search strategy | Not stated | 16 | 13 | Not stated |

| Yaphe et al41 | Journal article, systematic review | Clinical trials | Randomised controlled | Hand search of 5 major medical journals | 8 October 1992 to 1 October 1994 | 209 | 96 | Funded by company; provision of study materials by company; author was company employee; statistical analysis done by company |

Additional data from author.

Additional data from Freidberg et al.23

Additional data from Massie et al.42

For cost effectiveness: number of ratios (studies contained more than one ratio; 70 ratios from pharmaceutical company funded studies and 7 from device company funded studies); for quality: number of studies.

Three of us (LB, OC, JL), who were not blinded to study authors or results, independently abstracted information. We resolved disagreements by consensus.

On the basis of the rationale that funding does affect the direction of effect, we did a meta-analysis on the studies that reported the effects of funding on the outcome of either pharmacoeconomic analyses or clinical trials in cases where odds ratios could be computed. The homogeneity test showed that the effect size did not differ between the studies (P=0.17). Using a Mantel-Haenszel test, we constructed a pooled odds ratio.11 We used the program StatsDirect and considered P < 0.05 significant.

Results

Search results

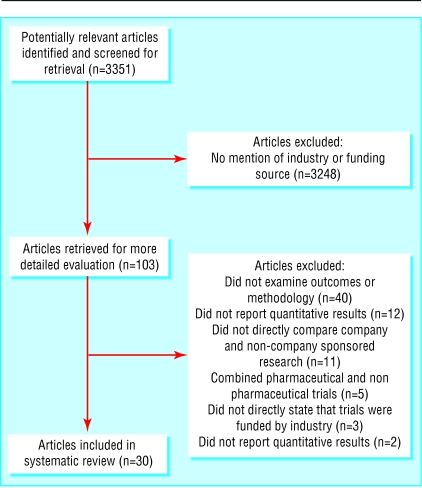

The combined searches and other data sources found 3351 potential titles. We scanned titles and abstracts (where available) for mention of the pharmaceutical industry in either the title or the abstract or any suggestion that the study would deal with industry funding. We read 103 articles in full (eight in languages other than English); we retained 30 articles for analysis. Reasons for exclusion are detailed in the QUOROM statement (fig 1).

Fig 1.

QUOROM statement

The studies by Friedberg et al23 and by Knox et al29 analysed the same set of 44 trials but looked at different aspects of the trials: conclusions about the usefulness of products in one case,23 and how the trials had been reported in the other.29 Only one article was duplicated in the two studies reported by the group including Chard, Tallon, and Dieppe13,18 (J Chard, personal communication, 2002). Seven of the nine articles in Kemmeren's27 meta-analysis of third generation oral contraceptives were also included in Vandenbroucke's meta-analysis.39 We found no other cases of double counting, but as some of the papers did not provide a full list of references we could not exclude the possibility of further overlap.

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 gives the characteristics of the 30 studies included in this analysis.12–41 Six were reviews of pharmacoeconomic reports,12,23,26,29,34,36 two reviewed meta-analyses and systematic reviews,18,25 and the remaining 22 analysed groups of clinical trials.13–17,19–22,24,27,28,30–33,35,37–41 Eleven papers mentioned that some trials were funded by industry but offered 22 further definition of industry funding.17,18,22,24–26,28,34,36,39,40 In the other 15 papers the definition varied from a statement acknowledging industry funding in the article12,32 to a more comprehensive definition.35

Relationship between source of funding and outcome

A total of 26 of the 30 studies reported results on the association of the outcome of the research and the source of funding: six examined the effects on publication,17,21,24,31,33,37 five looked at the outcome of pharmacoeconomic studies,12,23,26,34,36 and 16 analysed the outcome of clinical trials and meta-analyses of clinical trials (table 2).13–16,18–20,22,24,27,30,32,38–41

Table 2.

Relation between source of funding and outcome of research

| Author | Outcome question assessed by research | Results |

|---|---|---|

|

Funding source and publication status

|

|

|

| Dickersin et al17 | Factors associated with publication of findings from clinical trials | Publication rate at one of two centres was considerably higher for studies funded by National Institutes of Health than for studies funded by drug industry (90.5% v 65.0%), but no indication that there was any difference in the tendency to publish significant results |

| Easterbrook et al21 | Are clinical trials with statistically significant results more likely to be published and what is the magnitude of this bias | Drug company sponsored trials of any type are significantly less likely to be published or presented compared to unfunded studies (OR=0.36; 95% CI 0.16 to 0.81); drug company sponsored clinical trials are significantly less likely to be published or presented compared to unfunded studies (0.17; 0.05 to 0.53) |

| Ioannidis24 | Is time to completion and time to publication of clinical trials affected by statistical significance of results; description of natural history of trials | Trials where data managed by industry of shorter duration than those federally sponsored (P<0.01) but no difference in time to appearance in peer reviewed literature (P=0.33)† |

| Liebeskind et al31 | Evidence of publication bias in randomised controlled trials | Median time between enrolment and publication of industry funded studies with positive results 3.5 years v 4.7 years for negative studies; time difference for studies with any type of funding 3.5 v 4.4 years for industry funded studies |

| Massie et al33 | Whether source of funding of clinical trials on angina affected publication process | 48% of drug company funded trials published in symposium compared with 26% of studies with other types of funding or where source of funding not stated |

| Stern et al37 | Extent to which publication is influenced by study outcome | Pharmaceutical industry funding not a statistically significant predictor of time to publication |

|

Funding source and economic outcomes

|

|

|

| Azimi et al12 | How often do cost effectiveness analyses encourage a strategy requiring additional expenditures | Industry funded studies more likely to support a strategy requiring additional expenditures compared with those without such funding (9/10 v 15/34, P=0.01); among the 39 articles that supported additional expenditure the median cost effectiveness ratio of the 9 studies funded by industry was significantly higher than for the remainder (P=0.02) |

| Freidberg et al23 | Relation between drug company sponsorship and economic assessment of oncology drugs | Drug company sponsored studies more likely to report favourable qualitative conclusions (19/20 v 15/24, P=0.04); overstatement of quantitative results not significantly different (6/20 v 3/24, P=0.26) |

| Kamal-Bahl et al26 | Relation between drug company sponsorship and economic assessment of drugs for respiratory syncytial virus prophylaxis | Industry funded studies more likely to report possibility of cost effectiveness or cost savings of prophylaxis in entire high risk infant population either in point estimates or sensitivity analysis (4/4 v 0/8, P=0.002); when likelihood of reporting cost effectiveness or cost savings in either entire high risk populations or specific infant subgroups compared across studies, no difference between industry funded and non-industry funded studies (4/4 v 3/8, P=0.08) |

| Neumann et al34 | Relation between drug company sponsorship and cost effectiveness ratios and per cent cost saving reported | For incremental cost effectiveness ratio: industry funded studies $6000 v non-industry funded studies $13,000 (P=0.003); for per cent cost saving: industry funded studies 21% v non-industry funded studies 9% (P=0.002)‡ |

| Sacristan et al*36 | Relation between drug company sponsorship and results of cost effectiveness studies | General medical journals: 3/6 cost-effectiveness studies with industry funding had positive results v 31/63 with no funding or other source of funding; Pharmacoeconomics: 18/18 cost effectiveness studies with industry funding had positive results v 4/6 with no funding or other source of funding |

|

Funding source and outcomes of clinical trials and meta-analyses

|

|

|

| Chard et al13 | Results of clinical trials for osteoarthritis of the knee | Projects commercially funded more likely to support intervention than non-commercially or non-specified funding source studies (P=0.024)* |

| Cho et al14 | Relation between drug company sponsorship of clinical trials and study outcome | Proportion of trials with favourable outcome higher in drug company sponsored research than in trials without company sponsorship (39/40 v 89/112, P<0.01) |

| Clifford et al15 | Relation between funding source and trial outcome | Studies favouring new product: industry only funding 30/44; mixed industry and non-industry funding 16/22; not for profit funding 15/28 (P=0.461) |

| Davidson16 | Relation between drug company sponsorship of clinical trials and study outcome | Studies supported by companies significantly more likely to support new therapies than trials with other sources of funding or where funding not stated (33/37 v 43/70, P=0.002) |

| Dieppe et al18 | Relation between drug company sponsorship and outcome of meta-analyses of treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee | Trend for meta-analyses sponsored by pharmaceutical industry to show a significant beneficial effect compared with meta-analyses with other source of funding or unknown sources of funding (16/18 v 81/117, P=0.084) |

| Djulbegovic et al19 | Relation between drug company sponsorship of clinical trials of erythropoietin and study outcome | Drug company funded trials showed positive results in 21/23 studies (P<0.0001) compared with 5/7 studies funded partially or completely with public resources (P=0.096) |

| Djulbegovic et al20 | Relation between drug company sponsorship of clinical trials of the treatment of multiple myeloma and study outcome | Drug company funded trials showed positive results in 26/35 studies (P=0.004) compared with 54/101 studies funded by non-profit making organisations (P=0.608) |

| Freemantle et al22 | Investigate potentially confounding factors which may affect clinical trials that assessed the relative efficacy of antidepressants | Most important structural predictor of outcome was trial sponsorship—trend towards increased efficacy of sponsor's drug (coefficient 0.097; 95% CI -0.03 to 0.23) |

| Ioannidis24 | Is time to completion and time to publication of clinical trials affected by statistical significance of results; description of course of trials | No significant correlation between presence of statistical significance, study accrual, and whether data managed by industry or not (all correlation coefficients P<0.2)§ |

| Kemmeren et al27 | Relation between drug company sponsorship and outcome of studies comparing effects of second and third generation oral contraceptives on risk of venous thromboembolism | Odds ratio 1.3 (95% CI 1.0 to 1.7) for studies directly funded by pharmaceutical industry v 2.3 (1.7 to 3.2) in other studies |

| Koepp et al30 | Relation between drug company sponsorship of clinical trials on tacrine and study outcome | 0/5 studies without corporate support found clinical benefit; 6/7 studies with corporate support found benefit (1 study could not be located) |

| Mandelkern32 | Relation between drug company sponsorship of clinical trials in psychiatry and study outcome | 16/16 drug company funded studies reported favourable outcome; 10/16 non-industry funded studies reported favourable outcome |

| Thomas et al38 | Relation between drug company funding studies comparing topical glucocorticosteroids and whether study favours product made by sponsoring company ¶ | Product tested favoured in trial: 37/48 in company funded trials v 12/22 in trials with other sources of funding (P<0.001) |

| Vandenbroucke et al39 | Relation between drug company sponsorship and outcome of studies comparing effects of second and third generation oral contraceptives on risk of venous thromboembolism | 1/9 studies without industry funding found no higher risk of venous thromboembolism (relative risk 1.5-4.0, summary relative risk 2.4); 4/4 industry funded studies found no higher risk (relative risk 0.8-1.5, summary relative risk 1.1) |

| Wahlbeck et al40 | Relation between drug company sponsorship of clinical trials on clozapine and study outcome | Odds of relapsing significantly in favour of clozapine in drug company sponsored trials (odds ratio 0.5; 95% Cl 0.3 to 0.7) compared with non-sponsored trials (0.4; 0.1 to 1.4); both drug company sponsored and non-sponsored trials suggested clozapine mediates clinically important improvement compared with older drugs but industry sponsored trials were more positive (0.4; 0.2 to 0.7 v 0.3; 0.1 to 0.7); industry sponsored trials reported significantly fewer early dropouts compared with older drugs (0.5; 0.4 to 0.7) but non-sponsored trials did not (0.6; 0.3 to 1.2) |

| Yaphe et al41 | Relation between sources of support of research and published outcomes of randomised controlled drug trials | Positive outcomes: 181/209 trials with industry funding v 62/96 with non-industry funding (odds ratio 3.45, 95% Cl 1.90 to 6.62) |

Results for all 128 commercially sponsored trials (114 funded by pharmaceutical industry).

56 completed trials (of 98 where data was not managed by pharmaceutical industry) included in analysis.

70 trials funded by pharmaceutical companies and 7 funded by device companies.

90 trials where full patient accrual completed (of 98 where data was not managed by pharmaceutical industry) included in analysis

Outcome of studies assessed by independent evaluators.

Funding source and publication status

Research funded by drug companies was less likely to be published or presented than research funded by other sources (table 2).17,21 Three studies looked at time to publication,24,31,37 and two of these found that company sponsored research took longer to be published than research with other sources of funding.24,31 Research funded by drug companies was also more likely to be published in the proceedings of symposiums than non-industry sponsored research.33

Funding source and economic outcomes

Pharmacoeconomic studies sponsored by the drug industry were more likely to report results favouring the sponsor's product than studies with other sources of funding in all five articles that examined this question.12,23,26,34,36 In three cases, however, the bias in favour of industry funded research depended on the particular question being posed23,26 or on where the pharmacoeconomic analyses were published.36

Funding source and outcomes of clinical trials and meta-analyses

Sixteen studies investigated the relationship between funding source and the outcomes of clinical trials and meta-analyses. Of these, 13 found that clinical trials and meta-analyses sponsored by drug companies favoured the product produced by the funder. Statistical significance for this finding was reported in eight of the 13 studies,13,14,16,19,20,38,40,41 and in another two there was a trend towards statistical significance.18,22 These studies covered a wide range of diseases, such as osteoarthritis of the knee,13,18 multiple myeloma,20 various psychiatric problems,32,40 Alzheimer's disease,30 and venous thromboembolism,39 and a wide range of drugs, such as tacrine,30 clozapine,40 third generation oral contraceptives,39 erythropoietin,19 antidepressants,22 and topical glucocorticosteroids.38 One study that found no difference looked at the outcome of trials of treatment for HIV and associated complications and in this case the trials were monitored by the National Institutes of Health.24 In one meta-analysis of third generation oral contraceptives,27 the risk of venous thromboembolism for non-industry funded research was higher than that for industry sponsored trials, although the increased risk for thromboembolic disease was significant in both cases. Another study found no difference in outcomes in research published in five leading medical journals.15

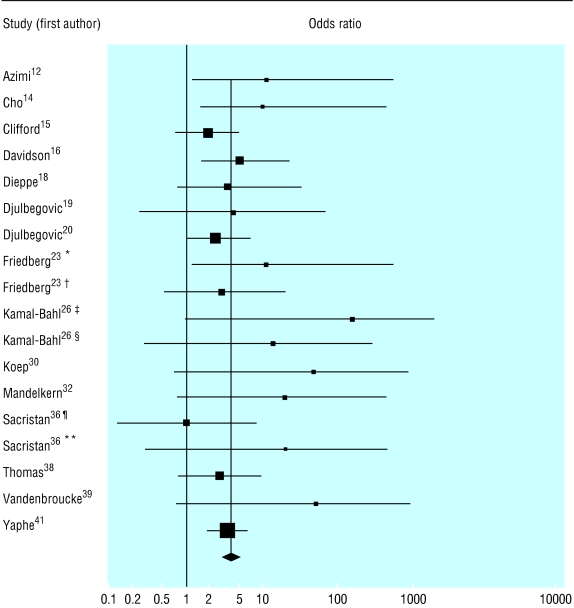

Figure 2 shows the individual odds ratios and summary odds ratio for 18 different comparisons (15 studies) of the outcomes of industry funded and non-industry funded studies—seven from pharmacoeconomic analyses and 11 from clinical trials or meta-analyses of clinical trials. The summary odds ratio was 4.05 (95% confidence interval 2.98 to 5.51).

Fig 2.

Source of funding and outcome in pharmacoeconomic analyses, clinical trials, and meta-analyses of clinical trials of drug treatments; for references see bmj.com (*Favourable qualitative results; †Overstatement of quantitative results; ‡Reporting possibility of cost effectiveness or cost savings of prophylaxis in entire high risk infant population either in point estimates or sensitivity analysis; §Reporting cost effectiveness or cost savings in either entire high risk populations or specific infant subgroups compared across studies; ¶Analyses reported in general medical journals; **Analyses reported in Pharmacoeconomics)

Relationship between source of funding and methodologic quality

A total of 13 studies examined the relationship between the source of funding and the methodological quality of the research (table 3).14–16,19,20,25,28,29,31–35 None of the 13 reported that industry funded studies had poorer methodological quality. Of the nine that provided statistical analyses, four found that drug company sponsored research had better quality scores.14,28,31,33

Table 3.

Relation between source of funding and methodological quality of research

| Study | Criteria used to assess methodological quality of research | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Cho et al14 | 22 item validated scoring system | Study design in drug company sponsored clinical trials better than in research where no stated sponsorship (P=0.04) |

| Clifford et al15 | 5 item validated scoring system (Jadad) plus component (individual items on Jadad scale and adequacy of concealment) approach | No difference by funding source for adequacy of allocation concealment (P=0.377); no difference by funding source for overall/composite score on Jadad scale (P=0.143) |

| Davidson16 | Sample size, blinding | For all trials higher rate of blinding for ones with industry sponsorship (67.5% v 41.8%, P=0.01); for trials investigating medications no difference in blinding (P=0.46); for sample size no difference between clinical trials supported by drug companies and those with other sources of funding or where funding not stated |

| Djulbegovic et al19 | 5 item validated scoring system (Jadad) | No difference in quality scores between randomised controlled trials funded solely by industry (mean 3.3 (SD 1.4); median: 3.5) and trials supported by public sources (mean 2 (SD 0.96); median: 2) (P=0.308) |

| Djulbegovic et al20 | 5 item validated scoring system (Jadad) | Randomised controlled trials funded solely or partly by industry had trend towards higher quality scores (mean 2.94 (SD 1.3); median: 3) than trials supported by government or other non-profit organisations (mean 2.4 (SD 0.8); median: 2) (P=0.06) |

| Jadad et al25 | 7 point validated scoring system (Guyatt and Oxman) | 6/6 industry funded systematic reviews and meta-analyses had serious flaws versus 34/44 non-industry funded reviews |

| Kjaergard et al28 | 5 point validated scale including: concealment of allocation, generation of allocation sequence, double blinding, dropouts/withdrawals, sample size | Clinical trials funded by either drug or device industry had higher quality than trials with no external funding (P<0.001); quality of publicly funded trials same as trials funded by drug or device industry (P=0.68) |

| Knox et al29 | 9 item scale developed for this study, including clinical design, generalisable data sources, statistical tests of significance performed on appropriate outcomes, statement regarding perspective, description of costs of the main included resources, description of time horizon, description of source of total costs differences, discussion of limitations, comparisons with other published studies | Drug company sponsored pharmacoeconomic analyses less likely to formally report on study generalisability, but were more likely to provide information on the key components of the methods section than were non-profit sponsored analyses |

| Liebeskind et al31 | 100 point scale addressing 5 aspects of trial design and reporting: randomisation, outcome, inclusion/exclusion criteria, description of therapeutic regimen, statistical analysis | Clinical trials with corporate support had better quality than trials with non-profit support (mean 73.1 (95% Cl 3.9) v 53.4 (9.8); P<0.0001) |

| Mandelkern32 | Presence or absence of placebo control | 5/16 industry funded clinical trials had placebo controls compared with 3/16 non-industry funded trials |

| Massie et al33 | Not stated | Higher proportion of industry funded clinical trials were adequately controlled and designed than were trials with other sources of funding (71% v 33%, P<0.01) |

| Neumann et al34 | Adherence to recommended protocols for cost effectiveness studies (adequate description of alternatives, study perspective clearly stated, discounted both costs and QALYs if needed, incremental analyses performed correctly) plus quality as judged by readers (scale of 1 to 7) | No difference between industry and non-industry funded studies on any measure: adequate description of alternatives P=0.30; study perspective clearly stated P=0.98; discounted both costs and QALYs P=0.65; incremental analyses performed correctly P=0.73; quality as judged by readers P=0.49 |

| Rochon et al35 | Modified version of Chalmers score including 14 items: control appearance and/or regimen, randomisation, blinding, patients blinded, observers blinded to treatment and results, previous estimate of numbers, testing compliance, results of randomisation on pretreatment variables and inclusion in analysis, major end points, post-beta estimate, confidence limits, statistical analyses, withdrawals after randomisation, side effects discussion | No difference in quality score between industry only funded clinical trials and those funded by government or foundations (mean 36.9% (SD 17.6%) v 37.1% (17.8%), P=0.271) |

QALY=quality adjusted life year.

Nine of the studies on clinical trials used well established methods of assessing quality.14,15,19,20,24,28,29,31,35 The single study that reported on the methods of pharmacoeconomic analyses used commonly accepted criteria for assessing cost effectiveness.34

One study evaluated the appropriateness of the comparators in clinical trials and found that a greater proportion of industry sponsored studies compared innovative treatment to either placebo or no therapy than did studies sponsored by public resources (60% v 21%; P < 0.001).20

Discussion

Research sponsored by the drug industry was more likely to produce results favouring the product made by the company sponsoring the research than studies funded by other sources. The results apply across a wide range of disease states, drugs, and drug classes, over at least two decades and regardless of the type of research being assessed—pharmacoeconomic studies, clinical trials, or meta-analyses of clinical trials. The totality of the evidence reported in our meta-analysis of a subset of homogeneous studies suggests that there is some kind of systematic bias to the outcome of published research funded by the pharmaceutical industry.

Our results confirm and extend those reported by Bekelman et al.8 They identified only five studies that compared outcomes in research funded by pharmaceutical companies and other sources,14,16,20,23,41 and our study adds another 16 studies12,13,15,18,19,22,24,26,27,30,32,34,36,38–40 Our results are also supported by Rochon and coworkers43 (we excluded this paper because all of the trials were sponsored by drug companies and were, therefore, not comparible with trials lacking company funding.) They found that trials supported by manufacturers of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents almost always reported that the sponsor's drug was as or more effective and less toxic than the comparison drug.

Explanations

At least four possible explanations exist for favourable results seen in industry sponsored research. Firstly, pharmaceutical companies may selectively fund trials on drugs that they consider to be superior to the competition. Data collected so far, however, indicate that researchers cannot predict results of trials in advance.44

Secondly, positive results could be the consequence of poor quality research conducted by industry. For example, low quality trials exaggerate the benefits of treatment by an average of 34%.45,46 We found that the research methods of trials sponsored by drug companies is at least as good as that of non-industry funded research and in many cases better. This does not guarantee the absence of bias in studies sponsored by the industry since outcome could be influenced by factors left out of quality scores, such as the question asked or the conduct or reporting of the study.7,47

Thirdly, selecting an appropriate comparator is a key issue in planning a clinical trial.7,20,44 In the study by Rochon et al, in most cases in which the doses of the study and comparator drugs were not equivalent, the drug given at the higher dose was that of the supporting manufacturer.43 As the authors saw, higher doses may bias the results in favour of effectiveness of the manufacturer's product. Safer also reports that in trials of psychiatric drugs the comparator drug is often given in doses outside the usual range or there is a rapid and substantial dose increase in the drug not manufactured by the sponsoring company.48 In another instance, research funded by the company marketing fluconazole compared it with oral amphotericin B, a drug known to be poorly absorbed, thereby creating a bias in favour of fluconazole.49 We did not consider who is finally responsible for the selection of the comparator—investigators, regulatory agencies, or sponsors.

Finally, our results suggest that publication bias may explain our finding of bias in favour of outcomes of research funded by industry. Although research sponsored by industry was less likely to be published than research with other sources of funding, the two studies with this finding did not specifically examine whether non-publication applied just to research with non-significant outcomes.17,21 In the past few years, manufacturers have attempted to prevent studies which are unfavourable to their products from being published in several high profile cases.50–52

Massie and colleagues raise another possible source of publication bias.33 They showed that research funded by industry appears more often in symposiums. Studies in symposiums are known to lack peer review and to favour the sponsor's product.14,53 Although the methods of industry funded trials are at least equal to those in studies funded by other sources, the absence of peer review may result in an overly favourable interpretation of the results of a trial. Rochon and colleagues noted that claims of superiority for the sponsor's product were often not supported by the data.43

Limitations

Our study has several limitations, primarily the difficulty in locating research examining the effects of company sponsorship. Our Medline and Embase searches found only 13 of the papers that we included,16–18,20,23,27–30,32,38,40,41 and the remaining 17 came from a search of the authors' personal files, suggestions by outside experts, or scanning of reference lists.12–15,19,21,22,24–26,31,33–37,39 The inability to critically evaluate the methodology in the abstracts and journal letters is another possible source of bias, and the conclusions of two of the letters that we included30,40 have been criticised.54,55

Methods in studies sponsored by industry were at least as good as in studies with other sources of funding. Conclusions about overall quality can be influenced by the instrument used,9 and some of the scales may have missed important criteria.

What is already known on this topic

When a pharmaceutical company funds research into drugs, studies are likely to produce results favourable to the sponsoring company's product

What this study adds

Research funded by drug companies was more likely to have outcomes that favour the sponsor's product than research funded by other sources

This cannot be explained by the reported quality of the methods in research sponsored by industry

The result may be due to inappropriate comparators or to publication bias

Research sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry is facing a number of challenges. Questions have been raised about the mismatch between the research agendas of the pharmaceutical industry and consumers of research.56 Meta-analysts are confronted with the problems of duplicate publication of data from company funded trials and the withholding of data.49,57,58

Leading medical journals recently decided to establish more rigorous criteria for the acceptance of research sponsored by industry; this is a step in the right direction towards increasing the credibility of studies paid for by drug companies.58 The revised CONSORT statement should also help improve the quality of clinical research.59,60 In addition, authors and editors should consider including a statement concerning prior beliefs of the investigators about the uncertainty of the treatments that are reported. Finally, all clinical trials should be registered prospectively as the only way to prevent publication bias.61 The proposal to do so which was put forward in 198662 has been periodically renewed,63–65 but to this date has not been implemented.

We thank Jiri Chard, David Liebeskind, Paula Rochon, and José Sacristan for additional information and data about their studies.

Contributors: JL conceived and planned the study, did the Medline search, extracted the data, and wrote the paper. LAB planned the study, extracted the data, and wrote the paper. BD planned the study, checked the data extraction process, and wrote the paper. OC extracted the data and wrote the paper. JL is guarantor.

Funding: No additional funding.

Competing interests: BD has been funded by several pharmaceutical companies to perform research and has received speaking honorariums.

References

- 1.Wyatt J. Use and sources of medical knowledge. Lancet 1991;338: 1368-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson JJ, Felson DT, Meenan RF. Secular changes in published clinical trials of second-line agents in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1991;34: 1304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorman PJ, Counsell C, Sandercock P. Reports of randomized trials in acute stroke, 1955 to 1995: what proportions were commercially sponsored? Stroke 1999;30: 1995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. 2001 industry profile. Washington, DC: PhRMA, 2003. www.phrma.org/publications/publications/profile02/index.cfm (accessed 6 May 2003).

- 5.Anis AH, Gagnon Y. Using economic evaluations to make formulary coverage decisions: so much for guidelines. Pharmacoeconomics 2000;18: 55-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill SR, Mitchell AS, Henry DA. Problems with the interpretation of pharmacoeconomic analyses: a review of submissions to the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. JAMA 2000;283: 2116-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bero LA, Rennie D. Influences on the quality of published drug studies. Int J Tech Assess Health Care 1996;12: 209-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. JAMA 2003;289: 454-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jüni P, Witschi A, Bloch R, Egger M. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA 1999;282: 1054-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berlin J, Rennie D. Measuring the quality of trials: the quality of quality scales. JAMA 1999;282: 1083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in medicine. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1987.

- 12.Azimi NA, Welch HG. The effectiveness of cost-effectiveness analysis in containing costs. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13: 664-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chard JA, Tallon D, Dieppe PA. Epidemiology of research into interventions for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee joint. Ann Rheum Dis 2000;59: 414-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho MK, Bero LA. The quality of drug studies published in symposium proceedings. Ann Intern Med 1996;124: 485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clifford TJ, Moher D, Barrowman N. Funding source, trial outcome and reporting quality: are they related? Results of a pilot study. www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/2/18 (accessed 6 May 2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Davidson RA. Source of funding and outcome of clinical trials. J Gen Intern Med 1986;1: 155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickersin K, Min Y-I, Meinert CL. Factors influencing publication of research results: follow-up of applications submitted to two institutional review boards. JAMA 1992;267: 374-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dieppe P, Chard J, Tallon D, Egger M. Funding clinical research. Lancet 1999;353: 1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Djulbegovic B, Bennett CL, Lyman GH. Violation of the uncertainty principle in conduct of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of erythropoietin (EPO). Blood 1999;94(suppl 1): 399A. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Djulbegovic B, Lacevic M, Cantor A, Fields KK, Bennett CL, Adams JR, et al. The uncertainty principle and industry-sponsored research. Lancet 2000;356: 635-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 1991;337: 867-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freemantle N, Anderson IM, Young P. Predictive value of pharmacological activity for the relative efficacy of antidepressant drugs: meta-regression analysis. Br J Psychiatr 2000;177: 292-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedberg M, Saffran B, Stinson TJ, Nelson W, Bennett CL. Evaluation of conflict of interest in economic analyses of new drugs used in oncology. JAMA 1999;282: 1453-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ioannidis JPA. Effect of the statistical significance of results on the time to completion and publication of randomized efficacy trials. JAMA 1998;279: 281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jadad AR, Moher M, Browman GP, Booker L, Sigouin C, Fuentes M, et al. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses on treatment of asthma: critical evaluation. BMJ 2000;320: 537-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamal-Bahl S, Doshi J, Campbell J. Economic analyses of respiratory syncytial virus immunoprophylaxis in high-risk infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156: 1034-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kemmeren JM, Algra A, Grobbee DE. Third generation oral contraceptives and risk of venous thrombosis: meta-analysis. BMJ 2001;323: 1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kjaergard LL, Nikolova D, Gluud C. Randomized clinical trials in Hepatology: predictors of quality. Hepatology 1999;30: 1134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knox KS, Adams JR, Djulbegovic B, Stinson TJ, Tomori C, Bennett CL. Reporting and dissemination of industry versus non-profit sponsored economic analyses of six novel drugs used in oncology. Ann Oncol 2000;11: 1591-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koepp R, Miles SH. Meta-analysis of tacrine for Alzheimer Disease: the influence of industry sponsors. JAMA 1999;281: 2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liebeskind DS, Kidwell CS, Saver JL. Empiric evidence of publication bias affecting acute stroke clinical trials. Stroke 1999;30: 268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandelkern M. Manufacturer support and outcome. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60: 122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Massie BM, Rothenberg D. Publication of sponsored symposiums in medical journals. N Engl J Med 1993;328: 1196-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neumann PJ, Sandberg EA, Bell CM, Stone PW, Chapman RH. Are pharmaceuticals cost-effective? A review of the evidence. Health Affairs 2000;19(2): 92-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH, Cheung M, Hayes JA, Chalmers TC. Evaluating the quality of articles published in journal supplements compared with the quality of those published in the parent journal. JAMA 1994;272: 108-113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sacristán JA, Bolaños E, Hernández JM, Soto J, Galende I. Publication bias in health economic studies. Pharmacoeconomics 1997;11: 289-91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stern JM, Simes RJ. Publication bias: evidence of delayed publication in a cohort study of clinical research projects. BMJ 1997;315: 640-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas PS, Tan K-S, Yates DH. Sponsorship, authorship, and accountability. Lancet 2002;359: 351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vandenbroucke JP, Helmerhorst FM, Rosendaal FR. Competing interests and controversy about third generation oral contraceptives. BMJ 2000;320: 381-2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wahlbeck K, Adams C. Sponsored drug trials show more-favourable outcomes. BMJ 1999;318: 465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yaphe J, Edman R, Knishkowy B, Herman J. The association between funding by commercial interests and study outcome in randomized controlled drug trials. Family Practice 2001;18: 565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Massie BM, Rothenberg D. Impact of pharmaceutical industry funding of clinical research: results of a survey of antianginal trials. Circulation 1984;70(suppl II): 390S. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH, Simms RW, Fortin PR, Felson DT, Minaker KL, et al. A study of manufacturer-supported trials of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of arthritis. Arch Intern Med 1994;154: 157-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Djulbegovic B. Acknowledgment of uncertainty: a fundamental means to ensure scientific and ethical validity in clinical research. Cur Oncol Rep 2001;3: 389-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moher D, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Tugwell P, Moher M, Jones A, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized trials: implications for the conduct of meta-analyses. Health Technol Assess 1999;3(12): 1-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moher D, Pham B, Jones D, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M, et al. Does quality of reports of randomized trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analysis? Lancet 1998;352: 609-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gotzsche P. Methodology and overt and hidden bias in reports of 196 double-blind trials of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Control Clin Trials 1989;10: 31-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Safer DJ. Design and reporting modifications in industry-sponsored comparative psychopharmacology trials. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002;190: 583-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johansen HK, Gotzsche PC. Problems in the design and reporting of trials of antifungal agents encountered during meta-analysis. JAMA 1999;282: 1752-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rennie D. Thyroid storm. JAMA 1997;277: 1238-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nathan DG, Weatherall DJ. Academia and industry: lessons from the unfortunate events in Toronto. Lancet 1999;353: 771-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCarthy M. Company sought to block paper's publication. Lancet 2000;356: 1659. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bero LA, Galbraith A, Rennie D. The publication of sponsored symposiums in medical journals. N Engl J Med 1992;327: 1135-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qizilbash N, Schneider L, Farlow M, Whitehead A, Higgins J. Meta-analysis of tacrine for Alzheimer Disease: the influence of industry sponsors. JAMA 1999;281: 2287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matthews JNS. Sponsored trials do not necessarily give more-favourable results. BMJ 1999;318: 1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tallon D, Chard J, Dieppe P. Relation between agendas of the research community and the research consumer. Lancet 2000;355: 2037-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huston P, Moher D. Redundancy, disaggregation, and the integrity of medical research. Lancet 1996;347: 1024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davidoff F, DeAngelis CD, Drazen JM, Højgaard L, Kotzin S, Nicholls MG, et al. Sponsorship, authorship, and accountability. N Engl J Med 2001;345: 825-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Altman DG, Schultz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, et al. The revised CONSORT statement: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2001;134: 663-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moher D, Schultz KF, Altman D, Lepage L. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA 2001;285: 1987-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Horton R, Smith R. Time to register randomized trials. Lancet 1999;354: 1138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Simes RJ. Publication bias: the case for an international registry of clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 1986;4: 1529-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meinert CL. Toward prospective registration of clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1988;9: 1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chalmers I. Underreporting research is scientific misconduct. JAMA 1990;263: 1405-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Horton R, Smith R. The time to register randomized trials. BMJ 1999;319: 865-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]