Abstract

A multilocus sequence typing (MLST) system was developed for group B streptococcus (GBS). The system was used to characterize a collection (n = 152) of globally and ecologically diverse human strains of GBS that included representatives of capsular serotypes Ia, Ib, II, III, V, VI, and VIII. Fragments (459 to 519 bp) of seven housekeeping genes were amplified by PCR for each strain and sequenced. The combination of alleles at the seven loci provided an allelic profile or sequence type (ST) for each strain. A subset of the strains were characterized by restriction digest patterning, and these results were highly congruent with those obtained with MLST. There were 29 STs, but 66% of isolates were assigned to four major STs. ST-1 and ST-19 were significantly associated with asymptomatic carriage, whereas ST-23 included both carried and invasive strains. All 44 isolates of ST-17 were serotype III clones, and this ST appeared to define a homogeneous clone that was strongly associated with neonatal invasive infections. The finding that isolates with different capsular serotypes had the same ST suggests that recombination occurs at the capsular locus. A web site for GBS MLST was set up and can be accessed at http://sagalactiae.mlst.net. The GBS MLST system offers investigators a valuable typing tool that will promote further investigation of the population biology of this organism.

Streptococcus agalactiae, group B streptococcus (GBS), is an important human pathogen. It is the leading cause of neonatal sepsis in the United Kingdom (18) and the United States (23). It is regarded as an emerging pathogen in the elderly (13) and is a frequent cause of maternal sepsis. However, GBS is usually a commensal organism and can be isolated from the genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts of up to 35% of healthy adults (1).

Capsular serotyping has been one of the mainstays in the descriptive epidemiology of GBS. Nine capsular serotypes have been described (Ia, Ib, and II to VIII). Serotype III GBS strains are of particular importance, as they are responsible for the majority of infections, including meningitis, in neonates worldwide (22). Diverse lineages of serotype III strains can be distinguished with multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (12, 19), pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (20), and restriction digest pattern (RDP) analysis (2), and the lineages appear to vary in pathogenic potential.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) is an unambiguous sequence-based typing method that involves sequencing approximately 500-bp fragments of seven housekeeping genes and has been used successfully to type strains and investigate the population structure of a number of human bacterial pathogens, including Neisseria meningitidis (16) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (9). MLST is particularly suitable for epidemiological studies because it provides data that can easily be compared between laboratories over the Internet.

The primary aim of this study was to develop an MLST system for GBS. Secondary aims were to show that the system could be used on a diverse globally derived collection of strains isolated from neonates and adults and that the system could distinguish between strains that were different with capsular serotyping and RDP typing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain collection.

The study collection consisted of 152 isolates of GBS from North America, New Zealand, Thailand, Singapore, Israel, Japan, and the United Kingdom. In addition, two well-characterized strains were included, the NCTC-8541 strain (isolated from a vaginal carrier; Public Health Laboratory, United Kingdom) and the NEM316 strain (ATCC 12403, isolated from a case of fatal neonatal sepsis, country of origin unknown), whose genome has been fully sequenced (11). The collection was globally diverse and included strains from asymptomatic carriers as well as human infections. Most capsular serotypes of GBS were represented, although serotypes IV and VII, which are rarely associated with disease in humans, were not included. Table 1 further describes the strain collection.

TABLE 1.

Collection of GBS strains used for development of the MLST systemlegend

| Country of origin | No. (%) of isolates

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal

|

Adult

|

Total | |||

| Carried | Invasive | Carried | Invasive | ||

| United Kingdom | 0 | 21 (13.9) | 20 (13.2) | 0 | 41 (27.1) |

| United States | 0 | 14 (9.2) | 6 (4.0) | 2 (1.2) | 22 (14.4) |

| Japan | 0 | 15 (9.9) | 30 (19.7) | 0 | 45 (29.6) |

| New Zealand | 2 (1.2) | 6 (4.0) | 5 (3.3) | 10 (6.6) | 23 (15.1) |

| Israel | 0 | 0 | 3 (2.0) | 7 (4.6) | 10 (6.6) |

| Singapore | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 6 (4.0) | 7 (4.6) |

| Thailand | 0 | 0 | 3 (2.0) | 0 | 3 (2.0) |

| Unknown* | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) |

| Total | 2 (1.2) | 58 (38.2) | 67 (44.2) | 25 (16.4) | 152 |

*NEM316 (ATCC 12403).

Identification of GBS.

Isolates were grown on blood agar and identified as group B streptococcus by the following criteria (21): β-hemolysis on a Columbia agar plate containing 5% horse blood (two strains of the 152 analyzed were nonhemolytic), Gram staining showing gram-positive cocci in pairs or short chains, negative reaction with catalase reagent, and Lancefield grouping with type B antisera (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom).

Characterization of strains.

Capsular serotyping was carried out on all strains in the laboratory of John Bohnsack. Capsular serotyping was repeated in a second laboratory with different method for 25 (16.5%) randomly selected isolates (Streptococcal Reference Laboratory, Central Public Health Laboratory, Colindale, United Kingdom [n = 20], and Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, KK Women's and Children's Hospital, Singapore [26] [n = 5]). Forty strains had previously been characterized by RDP (4).

DNA extraction.

The DNeasy kit (Qiagen GmbH) was used to extract DNA, and the gram-positive bacterial protocol was followed. A single colony of each strain was streaked across a Columbia agar plate containing 5% horse blood. Several colonies were picked off into phosphate-buffered saline and centrifuged at 5,500 × g. The cell pellet was resuspended in 180 μl of enzymatic lysis buffer containing lysozyme (20 mg/ml) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Then 25 μl of proteinase K (10 mg/ml) was added, and incubation was continued at 70°C for 30 min. The DNA in the clear viscous lysates was precipitated with 95% (vol/vol) ethanol and added to DNeasy minicolumns. Ethanol (70%, vol/vol)-based buffers AW1 and AW2 were added sequentially to the columns and centrifuged at 5,500 × g. The supernatants were discarded, and the DNA was resuspended in sterile water and stored at −20°C.

Choice of loci for MLST.

Ten candidate loci, encoding enzymes involved in intermediary metabolism, were identified by searching the genome sequence of the GBS strain NEM316 (11) with homologous sequences from other bacteria. Suitable genes were then chosen on the basis of chromosomal location and sequence diversity observed in pilot studies with a restricted set of GBS strains. Three genes were excluded, two because they failed to distinguish between GBS strains and one which was not reliably amplified. The following seven loci were selected for the MLST scheme (Table 2): alcohol dehydrogenase gbs0054 (adhP), phenylalanyl tRNA synthetase (pheS), amino acid transporter gbs0538 (atr), glutamine synthetase (glnA), serine dehydratase gbs2105 (sdhA), glucose kinase gbs0518 (glcK), and transketolase gbs2105 (tkt). The chromosomal locations of these housekeeping loci (Table 2) suggested that it was unlikely for any of them to be coinherited in the same recombination event, as the minimum distance between two loci was 20 kb.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of loci included in the GBS MLST systema

| Locus | Putative function of gene | Size of sequenced fragment (bp) | No. of alleles identified | No. (%) of polymorphic nucleotide sites | % G+C | dn/ds | Position in GBS genomeb (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adhP | Alcohol dehydrogenase (gbs0054) | 498 | 11 | 12 (2.4) | 43.1 | 0.13 | 72286 |

| pheS | Phenylalanyl tRNA synthetase | 501 | 5 | 7 (1.4) | 37.1 | 0.17 | 912817 |

| atr | Amino acid transporter (gbs0538) | 501 | 8 | 12 (2.4) | 36.9 | 0.14 | 560085 |

| glnA | Glutamine synthetase | 498 | 6 | 6 (1.2) | 35.7 | 0.12 | 1868862 |

| sdhA | Serine dehydratase (gbs2105) | 519 | 6 | 13 (2.5) | 41.4 | 0.12 | 2179923 |

| glcK | Glucose kinase (gbs0518) | 459 | 4 | 7 (1.5) | 42.6 | 0.13 | 538770 |

| tkt | Transketolase (gbs0268) | 480 | 5 | 8 (1.7) | 38.9 | 0.42 | 287111 |

Genes: adhP, alcohol dehydrogenase (gbs0054); pheS, phenylalanyl tRNA synthetase; atr, amino acid transporter (gbs0538); glnA, glutamine synthetase; sdhA, serine dehydratase (gbs2105); glcK, glucose kinase (gbs0518); tkt, transketolase (gbs2105). Alleles of the seven housekeeping loci can be obtained at http://sagalactiae.mlst.net.

From reference 11.

Amplification and nucleotide sequence determination.

PCR products were amplified with oligonucleotide primer pairs designed from the NEM316 GBS genome sequence (11). A range of primers were tested, with those shown in Table 3 providing reliable amplification from a diverse range of GBS isolates. Each 50-μl amplification reaction mixture comprised 10 ng of GBS chromosomal DNA, 100 pmol of each PCR primer (MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany), 1× PCR buffer with 1.5 mM MgCl2 (Qiagen GmbH), 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen GmbH), and 1.6 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix (ABgene, Epsom, United Kingdom). The reaction conditions were denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, primer annealing at 55°C for 45 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min for 30 cycles.

TABLE 3.

Oligonucleotide primers for GBS MLST

| Locus | Use | Name and sequence of primer

|

Amplicon size (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward (5′ to 3′) | Reverse (5′ to 3′) | |||

| adhP | Amplification | GTTGGTCATGGTGAAGCACT | ACTGTACCTCCAGCACGAAC | 672 |

| Sequencing | GGTGTGTGCCATACTGATTT | ACAGCAGTCACAACCACTCC | 498 | |

| pheS | Amplification | GATTAAGGAGTAGTGGCACG | TTGAGATCGCCCATTGAAAT | 723 |

| Sequencing | ATATCAACTCAAGAAAAGCT | TGATGGAATTGATGGCTATG | 501 | |

| atr | Amplification | CGATTCTCTCAGCTTTGTTA | AAGAAATCTCTTGTGCGGAT | 627 |

| Sequencing | ATGGTTGAGCCAATTATTTC | CCTTGCTCAACAATAATGCC | 501 | |

| glnA | Amplification | CCGGCTACAGATGAACAATT | CTGATAATTGCCATTCCACG | 589 |

| Sequencing | AATAAAGCAATGTTTGATGG | GCATTGTTCCCTTCATTATC | 498 | |

| sdhA | Amplification | AGAGCAAGCTAATAGCCAAC | ATATCAGCAGCAACAAGTGC | 646 |

| Sequencing | AACATAGCAGAGCTCATGAT | GGGACTTCAACTAAACCTGC | 519 | |

| glcK | Amplification | CTCGGAGGAACGACCATTAA | CTTGTAACAGTATCACCGTT | 607 |

| Sequencing | GGTATCTTGACGCTTGAGGG | ATCGCTGCTTTAATGGCAGA | 459 | |

| tkt | Amplification | CCAGGCTTTGATTTAGTTGA | AATAGCTTGTTGGCTTGAAA | 859 |

| Sequencing | ACACTTCATGGTGATGGTTG | TGACCTAGGTCATGAGCTTT | 480 | |

The amplification products were purified by precipitation with 20% polyethylene glycol and 2.5 M NaCl (8), and their nucleotide sequences were determined at least once on each DNA strand with internal nested primers (Table 3) and ABI Prism BigDye Terminators version 3.0 reaction mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Unincorporated dye terminators were removed by precipitation of the termination products with sodium acetate (3 M, pH 5.2) and 95% (vol/vol) ethanol, and the reaction products were separated and detected with an ABI Prism 3700 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Sequences were assembled from the resultant chromatograms with the Staden suite of computer programs and edited to resolve any ambiguities (24).

Allele and sequence type assignment.

For each locus, every different sequence was assigned a distinct allele number in order of identification; these were internal fragments of the gene which contained an exact number of codons. Any change in the nucleotide sequence, whether or not the amino acid sequence was altered, was defined as a new allele. Each isolate was therefore designated by a seven-integer number, constituting its allelic profile. Isolates with the same allelic profile were assigned to the same sequence type (ST), which were numbered in the order of their identification (ST-1, ST-2, etc.). The data have been deposited in a database accessible on the Internet at http://sagalactiae.mlst.net.

Computational analyses.

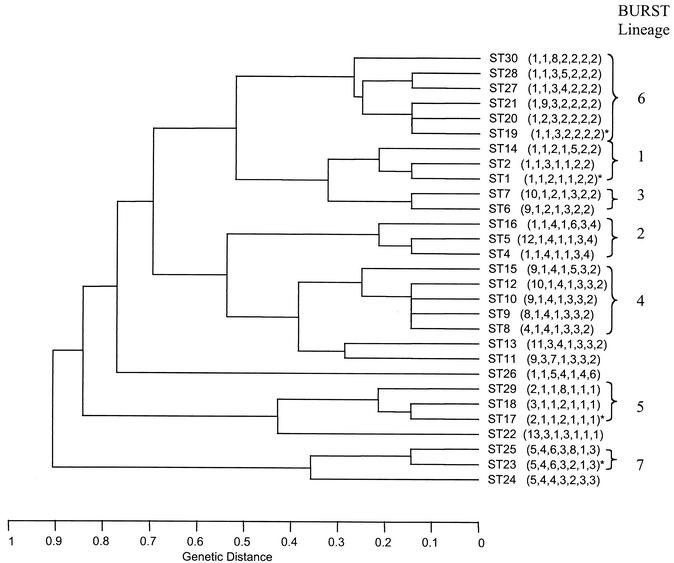

Determination of the number of polymorphic nucleotide sites, calculation of dn/ds, where dn is nonsynonymous substitutions and ds is synonymous substitutions, and construction of dendrograms with the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) were performed with START (http://www.mlst.net) (14). STs were grouped into lineages or clonal complexes with BURST (START version 1.05, http://www.mlst.net [14]). The members of a BURST lineage were defined as groups of two or more independent isolates where each isolate had identical alleles at six or more loci with at least one other member of the group.

RESULTS

Variation at the seven MLST loci.

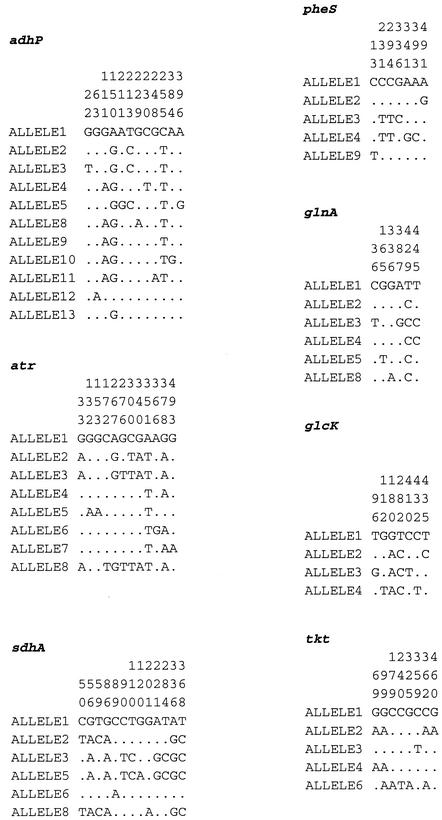

The sequences of the seven chosen loci were determined for the 152 strains, and allelic profiles were assigned. The alleles defined for the MLST scheme were based on sequence lengths of between 459 (glcK) and 519 bp (sdhA). Between four (glcK) and 11 alleles (adhP) were present at each locus. The average number of alleles at each locus was 6.4, providing the potential to distinguish 4.4 × 105 different genotypes. The proportion of variable nucleotide sites present in the selected housekeeping genes ranged from 1.2% (glnA) to 2.5% (sdhA) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). The proportions of nucleotide alterations that changed the amino acid sequence (nonsynonymous substitutions, dn) and the proportions of silent changes (synonymous substitutions, ds) were calculated for each gene. With these data, the dn/ds ratios were calculated for all seven loci and were all <1 (Table 2).

FIG. 1.

Polymorphic nucleotide sites in GBS MLST genes. Only the variable sites are shown. The nucleotide at each site is shown for allele 1; only those that differ from the nucleotide in allele 1 are shown for the other alleles. Nucleotide sites are numbered in vertical format.

Relatedness of GBS isolates.

The 152 isolates were resolved into 29 STs, 14 of which were identified only once (Table 4). One hundred and one isolates (66.5% of the data set) were represented by one of four STs, ST-1, ST-17, ST-19, and ST-23. The most common ST (ST-17) was identified 44 times in the data set, followed by ST-1 (21 isolates), ST-19 (20 isolates), and ST-23 (16 isolates). ST-3 was not identified in this data set but had been identified in a pilot study. UPGMA was used to construct a dendrogram from the matrix of pairwise allelic differences between the 29 STs of all 152 isolates (Fig. 2). BURST grouped the isolates into seven lineages (Fig. 2), which approximated well with the clusters of STs obtained by UPGMA.

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of GBS isolates according to STa

| ST | Allelic profile | No. of iso- lates in ST | Serotype (no. of isolates) | Source (no. of isolates) | Country of origin (no. of isolates) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 2, 2 | 21 | V (9), VIII (4), VI (4), III (2), Ib (1), NT (1) | AC (16), AI (3), NI (2) | J (10), UK (4), Is (3), NZ (3), T (1) |

| 2 | 1, 1, 3, 1, 1, 2, 2 | 2 | II (1), NT (1) | AI (2) | Is (1), NZ (1) |

| 4 | 1, 1, 4, 1, 1, 3, 4 | 2 | Ia (2) | AC (1), NI (1) | J (1), UK (1) |

| 5 | 12, 1, 4, 1, 1, 3, 4 | 1 | Ia (1) | AC (1) | J (1) |

| 6 | 9, 1, 2, 1, 3, 2, 2 | 1 | Ib (1) | AC (1) | UK (1) |

| 7 | 10, 1, 2, 1, 3, 2, 2 | 3 | Ia (3) | AC (1), NI (2) | J (3) |

| 8 | 4, 1, 4, 1, 3, 3, 2 | 7 | Ib (6), NT (1) | AC (4), NI (1), AI (2) | UK (3), NZ (2), J (1), S (1) |

| 9 | 8, 1, 4, 1, 3, 3, 2 | 1 | Ib (1) | AC (1) | Is (1) |

| 10 | 9, 1, 4, 1, 3, 3, 2 | 5 | Ib (3), II (1), NT (1) | AC (2), NI (1), AI (2) | UK (2), NZ (2), J (1) |

| 11 | 9, 3, 7, 1, 3, 3, 2 | 5 | III (5) | AI (5) | S (5) |

| 12 | 10, 1, 4, 1, 3, 3, 2 | 3 | Ib (3) | NI (2), AC (1) | J (2), UK (1) |

| 13 | 11, 3, 4, 1, 3, 3, 2 | 1 | VI (1) | AC (1) | T (1) |

| 14 | 1, 1, 2, 1, 5, 2, 2 | 1 | VI (1) | AC (1) | T (1) |

| 15 | 9, 1, 4, 1, 5, 3, 2 | 2 | Ib (2) | AI (1), NI (1) | NZ (2) |

| 16 | 1, 1, 4, 1, 6, 3, 4 | 1 | Ia (1) | AI (1) | Is (1) |

| 17 | 2, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1 | 44 | III (44) | NI (33), AC (9), AI (2) | US (16), J (14), UK (13), NZ (1) |

| 18 | 3, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1 | 1 | III (1) | NI (1) | UK (1) |

| 19 | 1, 1, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2 | 20 | III (17), II (1), V (1), NT (1) | AC (14), NI (3) AI (2), NC (1) | UK (8), NZ (5), US (5), J (2) |

| 20 | 1, 2, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2 | 1 | III (1) | NI (1) | UK (1) |

| 21 | 1, 9, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2 | 1 | III (1) | NI (1) | J (1) |

| 22 | 13, 3, 1, 3, 1, 1, 1 | 2 | II (2) | AC (1), AI (1) | Is (2) |

| 23 | 5, 4, 6, 3, 2, 1, 3 | 16 | Ia (11), III (4), V (1) | AC (7), NI (5), AI (3), NC (1) | NZ (7), UK (3), J (3), Is (1), S (1), NK (1) |

| 24 | 5, 4, 4, 3, 2, 3, 3 | 1 | Ia (1) | AC (1) | UK (1) |

| 25 | 5, 4, 6, 3, 8, 1, 3 | 1 | III (1) | NI (1) | US (1) |

| 26 | 1, 1, 5, 4, 1, 4, 6 | 3 | V (3) | AC (2), NI (1) | J (2), UK (1) |

| 27 | 1, 1, 3, 4, 2, 2, 2 | 1 | III (1) | AI (1) | Is (1) |

| 28 | 1, 1, 3, 5, 2, 2, 2 | 3 | II (3) | AC (2), NI (1) | J (2), UK (1) |

| 29 | 2, 1, 1, 8, 1, 1, 1 | 1 | III (1) | NI (1) | J (1) |

| 30 | 1, 1, 8, 2, 2, 2, 2 | 1 | V (1) | AC (1) | J (1) |

Abbreviations: ST, sequence type; NT, nontypeable; A, adult; N, neonatal; I, invasive disease; C, carried strain; J, Japan; UK, United Kingdom; Is, Israel; NZ, New Zealand; T, Thailand; S, Singapore; NK, not known. Allelic profiles for each gene are presented in the order adhP, pheS, atr, glnA, sdhA, glcK, tkt.

FIG. 2.

UPGMA dendrogram showing genetic relationships between the 29 STs. The allelic profile of each ST is shown in parentheses. The four most common STs are indicated by an asterisk.

Relationship between ST, capsular serotype, and restriction digest patterns.

Capsular serotype was known for all 152 strains (Table 5), and there was complete correlation between capsular serotyping results among three laboratories. Five strains proved to be nontypeable. Serotype III was most common (78 strains, 44 of which belonged to ST-17), followed by serotypes Ia (19 strains), Ib (17 strains), V (15 strains), II (8 strains), VI (6 strains), and VIII (4 strains). Serotypes IV and VII were not represented in the data set. Capsular serotype was generally not restricted to specific STs, and four STs contained isolates with different capsular serotypes.

TABLE 5.

The collection of 152 isolates of GBS described according to ST, country of isolation, host type, epidemiology, and capsule typea

| Isolate no. | ST | Country | Host | Epidemiology | Capsule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS11 | 1 | Is | A | C | V |

| IS19 | 1 | Is | A | I | V |

| IS2 | 1 | Is | A | I | V |

| U64 | 1 | J | A | C | III |

| U65 | 1 | J | A | C | III |

| U88 | 1 | J | A | C | VI |

| U89 | 1 | J | A | C | VI |

| U90 | 1 | J | A | C | VI |

| U92 | 1 | J | A | C | VI |

| U93 | 1 | J | A | C | VIII |

| U94 | 1 | J | A | C | VIII |

| U95 | 1 | J | A | C | VIII |

| U96 | 1 | J | A | C | VIII |

| NZ14 | 1 | NZ | N | I | V |

| NZ18 | 1 | NZ | A | C | V |

| NZ23 | 1 | NZ | A | I | V |

| T3 | 1 | T | A | C | NT |

| Z12 | 1 | UK | A | C | V |

| Z84 | 1 | UK | A | C | V |

| Z95 | 1 | UK | A | C | V |

| UK22 | 1 | UK | N | I | Ib |

| IS28 | 2 | Is | A | I | NT |

| NZ7 | 2 | NZ | A | I | II |

| U63 | 4 | J | A | C | Ia |

| UK6 | 4 | UK | N | I | Ia |

| U62 | 5 | J | A | C | Ia |

| Z78 | 6 | UK | A | C | Ib |

| U72 | 7 | J | A | C | Ia |

| U75 | 7 | J | N | I | Ia |

| U71 | 7 | J | N | I | Ia |

| U79 | 8 | J | A | C | Ib |

| NZ19 | 8 | NZ | A | I | Ib |

| NZ4 | 8 | NZ | A | I | Ib |

| A8 | 8 | S | A | I | NT |

| Z111 | 8 | UK | A | C | Ib |

| Z72 | 8 | UK | A | C | Ib |

| UK13 | 8 | UK | N | I | Ib |

| IS13 | 9 | Is | A | C | Ib |

| U78 | 10 | J | N | I | Ib |

| NZ17 | 10 | NZ | A | I | Ib |

| NZ20 | 10 | NZ | A | I | II |

| Z73 | 10 | UK | A | C | Ib |

| Z41 | 10 | UK | A | C | NT |

| A2 | 11 | S | A | I | III |

| A3 | 11 | S | A | I | III |

| A4 | 11 | S | A | I | III |

| A5 | 11 | S | A | I | III |

| A6 | 11 | S | A | I | III |

| U80 | 12 | J | N | I | Ib |

| U81 | 12 | J | N | I | Ib |

| Z69 | 12 | UK | A | C | Ib |

| T5 | 13 | T | A | C | VI |

| T1 | 14 | T | A | C | VI |

| NZ15 | 15 | NZ | A | I | Ib |

| NZ16 | 15 | NZ | N | I | Ib |

| IS56 | 16 | Is | A | I | Ia |

| U11 | 17 | J | A | C | III |

| U23 | 17 | J | A | C | III |

| U25 | 17 | J | A | C | III |

| U3 | 17 | J | A | C | III |

| U4 | 17 | J | A | C | III |

| U5 | 17 | J | A | C | III |

| U1 | 17 | J | N | I | III |

| U12 | 17 | J | N | I | III |

| U13 | 17 | J | N | I | III |

| U14 | 17 | J | N | I | III |

| U15 | 17 | J | N | I | III |

| U2 | 17 | J | N | I | III |

| U26 | 17 | J | N | I | III |

| U24 | 17 | J | N | I | III |

| NZ10 | 17 | NZ | N | I | III |

| Z34 | 17 | UK | A | C | III |

| Z37 | 17 | UK | A | C | III |

| UK3 | 17 | UK | N | I | III |

| UK4 | 17 | UK | N | I | III |

| UK5 | 17 | UK | N | I | III |

| UK8 | 17 | UK | N | I | III |

| UK10 | 17 | UK | N | I | III |

| UK12 | 17 | UK | N | I | III |

| UK15 | 17 | UK | N | I | III |

| UK17 | 17 | UK | N | I | III |

| UK20 | 17 | UK | N | I | III |

| UK21 | 17 | UK | N | I | III |

| UK18 | 17 | UK | N | I | III |

| U21 | 17 | USA | A | I | III |

| U22 | 17 | USA | A | I | III |

| U29 | 17 | USA | A | C | III |

| U10 | 17 | USA | N | I | III |

| U17 | 17 | USA | N | I | III |

| U19 | 17 | USA | N | I | III |

| U20 | 17 | USA | N | I | III |

| U27 | 17 | USA | N | I | III |

| U28 | 17 | USA | N | I | III |

| U31 | 17 | USA | N | I | III |

| U7 | 17 | USA | N | I | III |

| U8 | 17 | USA | N | I | III |

| U9 | 17 | USA | N | I | III |

| U18 | 17 | USA | N | I | III |

| U30 | 17 | USA | N | I | III |

| U32 | 17 | USA | N | I | III |

| UK11 | 18 | UK | N | I | III |

| U54 | 19 | J | A | C | III |

| U84 | 19 | J | A | C | V |

| NZ1 | 19 | NZ | A | I | III |

| NZ11 | 19 | NZ | A | C | III |

| NZ2 | 19 | NZ | N | I | III |

| NZ21 | 19 | NZ | A | I | III |

| NZ3 | 19 | NZ | N | C | III |

| UK16 | 19 | UK | A | C | III |

| Z101 | 19 | UK | A | C | III |

| Z117 | 19 | UK | A | C | III |

| Z77 | 19 | UK | A | C | II |

| 8541 | 19 | UK | A | C | NT |

| Z50 | 19 | UK | A | C | III |

| UK7 | 19 | UK | N | I | III |

| UK19 | 19 | UK | N | I | III |

| U55 | 19 | USA | A | C | III |

| U56 | 19 | USA | A | C | III |

| U57 | 19 | USA | A | C | III |

| U58 | 19 | USA | A | C | III |

| U59 | 19 | USA | A | C | III |

| UK1 | 20 | UK | N | I | III |

| U53 | 21 | J | N | I | III |

| IS1 | 22 | Is | A | I | II |

| IS12 | 22 | Is | A | C | II |

| IS9 | 23 | Is | A | I | III |

| U69 | 23 | J | A | C | Ia |

| U70 | 23 | J | A | C | Ia |

| U60 | 23 | J | A | C | III |

| NZ12 | 23 | NZ | N | I | Ia |

| NZ13 | 23 | NZ | N | C | Ia |

| NZ22 | 23 | NZ | A | I | Ia |

| NZ5 | 23 | NZ | N | I | III |

| NZ6 | 23 | NZ | A | C | Ia |

| NZ8 | 23 | NZ | A | C | Ia |

| NZ9 | 23 | NZ | A | I | Ia |

| A7 | 23 | S | N | I | Ia |

| Z81 | 23 | UK | A | C | Ia |

| Z87 | 23 | UK | A | C | V |

| UK14 | 23 | UK | N | I | Ia |

| NEM316 | 23 | NK | N | I | III |

| Z18 | 24 | UK | A | C | Ia |

| U61 | 25 | USA | N | I | III |

| U86 | 26 | J | A | C | V |

| U87 | 26 | J | A | C | V |

| UK2 | 26 | UK | N | I | V |

| IS31 | 27 | Is | A | I | III |

| U82 | 28 | J | A | C | II |

| U83 | 28 | J | A | C | II |

| UK9 | 28 | UK | N | I | II |

| U16 | 29 | J | N | I | III |

| U85 | 30 | J | A | C | V |

Abbreviations: ST, sequence type; NT, nontypeable; NK, not known; A, adult; N, neonatal; I, invasive strain; C, carried strain; J, Japan; UK, United Kingdom; Is, Israel; NZ, New Zealand; T, Thailand; S, Singapore.

RDP typing results were known for 40 of the isolates within the data set (Table 6). RDP type correlated closely with ST; isolates of the same RDP type were identical by MLST or differed at only a single locus.

TABLE 6.

Restriction digest patterns compared with ST for 40 GBS isolates

| ST | Allelic profile | RDP type | No. of strains |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | 2, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1 | III-3 | 30 |

| 29 | 2, 1, 1, 8, 1, 1, 1 | III-3 | 1 |

| 19 | 1, 1, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2 | III-2 | 6 |

| 21 | 1, 9, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2 | III-2 | 1 |

| 23 | 5, 4, 6, 3, 2, 1, 3 | III-1 | 1 |

| 25 | 5, 4, 6, 3, 8, 1, 3 | III-1 | 1 |

Relationship between lineage, host, and country of origin.

The data set presented in this study was not specifically designed to investigate the relationship between isolates and country or host of origin. However, the following observations can be made. ST-1 and ST-19 were significantly associated with carriage (chi-squared test, Yates corrected, P = 0.004 and P = 0.008, respectively), and several different capsular serotypes were represented in these STs. The 44 strains within ST-17 were all serotype III. ST-17 was significantly associated with invasive neonatal disease (chi-squared test, Yates corrected, P = 0.0000001). ST-23 contained serotype Ia strains (11 of 16, 68.6%) from carriage and invasive disease. ST-1, ST-19, ST-17, and ST-23 each contained strains isolated from Australasia, Europe, Asia, and North America, suggesting global dispersal.

DISCUSSION

We describe an MLST scheme for GBS based on seven housekeeping genes which was validated with a worldwide collection of capsule-typed strains that included a subgroup of strains previously characterized by RDP.

The percentage of variable sites (1.2 to 2.5%) in the seven selected GBS genes was comparable to that seen by Tettelin et al. (25) in their analysis of sequence variation in 19 genes from 11 GBS strains. The percentage of variable sites was less than that seen in the related species, group A streptococcus (10) (5.1 to 7.6%), and considerably less than that of Campylobacter jejuni (7) (9.2 to 21.7%), a gram-negative organism. The dn/ds ratios for the seven GBS genes were all less than 1, which suggests that there is selection against amino acid change and is consistent with most of the variation being selectively neutral. The genes chosen were distributed around the chromosome and were located in the same approximate locations in both of the published GBS genome sequences, NEM316 (11) and 2603V/R (25). MLST results for the two published GBS genome sequences showed that NEM316 was ST-23 and that 2603V/R was a single-locus variant of ST-19.

The DNA sequence data obtained with MLST are amenable to storage on Internet-based web sites (16), where the STs of strains from geographically distinct laboratories can be obtained and compared with those on a web-based MLST database. A web site for GBS MLST has been set up and can be accessed at http://sagalactiae.mlst.net. This offers investigators a valuable typing tool that will promote further epidemiological investigations of this organism. Studies investigating the differences between strains sampled in well-defined frames from neonatal invasive disease, adult disease, and carriage in humans or bovines with MLST will offer the opportunity of determining whether specific clones are associated with disease. Furthermore, analysis of the sequence data may give information on the evolutionary origins and transmission patterns of this organism.

The aim of this work was to establish an MLST typing system, but there were sufficient numbers of strains to make early observations about the population structure of GBS. The most common STs in the data set were ST-1, ST-17, ST-19, and ST-23. These four STs represented two-thirds of the strain collection. ST-19 and ST-1 contained several different capsular serotypes and were significantly associated with the carrier state. ST-17 was more homogeneous and consisted of serotype III strains predominantly associated with neonatal invasive disease. The STs were grouped together in similar fashion by UPGMA and Burst. A better understanding of the relationship between clones and clonal complexes and disease and the full extent of diversity in GBS will await the examination of much larger collections of diverse isolates that will now be possible.

The MLST findings are in accord with the results of Musser et al. (17). These authors used multilocus enzyme electrophoresis to study the population structure of GBS. They found that two distantly related evolutionary lineages of GBS could be distinguished. The first lineage contained a single electrophoretic type (ET-1) and consisted of serotype III isolates which had been isolated from neonatal disease. This presumably corresponds to ST-17 of MLST. The second lineage of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis was more diverse and contained several subdivisions and numerous electrophoretic types which may correspond to the ST-19 complex or ST-1 complex, which are more diverse, with several STs and different capsular serotypes. Similar relationships between GBS isolates have also been found by RDP typing (3) and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (20).

MLST shows that isolates with the same ST can have different capsular serotypes. This could imply that the MLST scheme has insufficient discriminatory power and groups isolates that are not closely related in genotype. However, a similar variation in the serotype of isolates within a single genotype was also shown by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (17). The variation in serotype within a single ST and the presence of genetically diverse isolates with the same serotype suggest that the capsular biosynthesis genes of GBS are subject to relatively frequent horizontal gene transfer, as is seen in Streptococcus pneumoniae (6). It has been demonstrated that a single gene confers serotype specificity in GBS of capsular types III and Ia (5), and recombinational replacement of this gene with that from an isolate of a different serotype would result in a change of capsular type. However, thus far, horizontal transfer of capsular genes has not been shown for GBS other than in the laboratory. An alternative, perhaps less likely explanation is that capsular serotyping may be prone to mistakes and is difficult to interpret. Confirmation of serotypic identity may be possible when a DNA sequence-based serotyping method is more readily available. Preliminary findings of one such method have recently been described (15).

In conclusion, the GBS MLST system appears to be sufficiently discriminatory for epidemiological studies and provides a precise and unambiguous way of characterizing isolates of GBS. The results have confirmed previous findings that a single clone of GBS (ST-17) seems to be frequently represented in neonatal invasive disease. ST-17 is a natural choice for future study of the virulence of GBS, and it is unfortunate perhaps that neither of the recently published genome sequences for GBS represent this important clone.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council and Action Research.

We acknowledge the following for provision of strains: N. Tee, Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, KK Women's and Children's Hospital, Singapore; D. Martin and J. Morgan, Communicable Disease, ESR, Porirua, New Zealand; N. White and J. Short, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; and Centre for Tropical Medicine, Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, United Kingdom. We also acknowledge A. A. Whiting (Department of Pediatrics, University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake City, Utah) for capsular serotyping of strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bliss, S. J., S. D. Manning, P. Tallman, C. J. Baker, M. D. Pearlman, C. F. Marrs, and B. Foxman. 2002. Group B streptococcus colonization in male and nonpregnant female university students: a cross-sectional prevalence study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:184-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohnsack, J. F., S. Takahashi, S. R. Detrick, L. R. Pelinka, L. L. Hammitt, A. A. Aly, A. A. Whiting, and E. E. Adderson. 2001. Phylogenetic classification of serotype III group B streptococci on the basis of hylB gene analysis and DNA sequences specific to restriction digest pattern type III-3. J. Infect. Dis. 183:1694-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohnsack, J. F., S. Takahashi, L. Hammitt, D. V. Miller, A. A. Aly, and E. E. Adderson. 2000. Genetic polymorphisms of group B streptococcus scpB alter functional activity of a cell-associated peptidase that inactivates C5a. Infect. Immun. 68:5018-5025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohnsack, J. F., A. A. Whiting, R. D. Bradford, B. K. Van Frank, S. Takahashi, and E. E. Adderson. 2002. Long-range mapping of the Streptococcus agalactiae phylogenetic lineage restriction digest pattern type III-3 reveals clustering of virulence genes. Infect. Immun. 70:134-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaffin, D. O., S. B. Beres, H. H. Yim, and C. E. Rubens. 2000. The serotype of type Ia and III group B streptococci is determined by the polymerase gene within the polycistronic capsule operon. J. Bacteriol. 182:4466-4477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coffey, T. J., M. C. Enright, M. Daniels, J. K. Morona, R. Morona, W. Hryniewicz, J. C. Paton, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Recombinational exchanges at the capsular polysaccharide biosynthetic locus lead to frequent serotype changes among natural isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 27:73-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dingle, K. E., F. M. Colles, D. R. Wareing, R. Ure, A. J. Fox, F. E. Bolton, H. J. Bootsma, R. J. Willems, R. Urwin, and M. C. Maiden. 2001. Multilocus sequence typing system for Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Embley, T. M. 1991. The linear PCR reaction: a simple and robust method for sequencing amplified rRNA genes. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 13:171-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enright, M. C., and B. G. Spratt. 1998. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology 144:3049-3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enright, M. C., B. G. Spratt, A. Kalia, J. H. Cross, and D. E. Bessen. 2001. Multilocus sequence typing of Streptococcus pyogenes and the relationships between emm type and clone. Infect. Immun. 69:2416-2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glaser, P., C. Rusniok, C. Buchrieser, F. Chevalier, L. Frangeul, T. Msadek, M. Zouine, E. Couve, L. Lalioui, C. Poyart, P. Trieu-Cuot, and F. Kunst. 2002. Genome sequence of Streptococcus agalactiae, a pathogen causing invasive neonatal disease. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1499-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauge, M., C. Jespersgaard, K. Poulsen, and M. Kilian. 1996. Population structure of Streptococcus agalactiae reveals an association between specific evolutionary lineages and putative virulence factors but not disease. Infect. Immun. 64:919-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henning, K. J., E. L. Hall, D. M. Dwyer, L. Billmann, A. Schuchat, J. A. Johnson, and L. H. Harrison. 2001. Invasive group B streptococcal disease in Maryland nursing home residents. J. Infect. Dis. 183:1138-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jolley, K. A., E. J. Feil, M. S. Chan, and M. C. Maiden. 2001. Sequence type analysis and recombinational tests (START). Bioinformatics 17:1230-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong, F., S. Gowan, D. Martin, G. James, and G. L. Gilbert. 2002. Serotype identification of group B streptococci by PCR and sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:216-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maiden, M. C., J. A. Bygraves, E. Feil, G. Morelli, J. E. Russell, R. Urwin, Q. Zhang, J. Zhou, K. Zurth, D. A. Caugant, I. M. Feavers, M. Achtman, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3140-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musser, J. M., S. J. Mattingly, R. Quentin, A. Goudeau, and R. K. Selander. 1989. Identification of a high-virulence clone of type III Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus) causing invasive neonatal disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:4731-4735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Public Health Laboratory Services. 2002. Incidence of group B streptococcal disease in infants aged less than 90 days. CDR Wkly. 12:3.

- 19.Quentin, R., H. Huet, F. S. Wang, P. Geslin, A. Goudeau, and R. K. Selander. 1995. Characterization of Streptococcus agalactiae strains by multilocus enzyme genotype and serotype: identification of multiple virulent clone families that cause invasive neonatal disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2576-2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rolland, K., C. Marois, V. Siquier, B. Cattier, and R. Quentin. 1999. Genetic features of Streptococcus agalactiae strains causing severe neonatal infections, as revealed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and hylB gene analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1892-1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schrag, S., R. Gorwitz, K. Fultz-Butts, and A. Schuchat. 2002. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease. Revised guidelines from CDC. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. Recommun. Rep. 51:1-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuchat, A. 1998. Epidemiology of group B streptococcal disease in the United States: shifting paradigms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:497-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schuchat, A. 1999. Group B streptococcus. Lancet 353:51-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staden, R. 1996. The Staden sequence analysis package. Mol. Biotechnol. 5:233-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tettelin, H., V. Masignani, M. J. Cieslewicz, J. A. Eisen, S. Peterson, M. R. Wessels, I. T. Paulsen, K. E. Nelson, I. Margarit, T. D. Read, L. C. Madoff, A. M. Wolf, M. J. Beanan, L. M. Brinkac, S. C. Daugherty, R. T. DeBoy, A. S. Durkin, J. F. Kolonay, R. Madupu, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, N. B. Fedorova, D. Scanlan, H. Khouri, S. Mulligan, H. A. Carty, R. T. Cline, S. E. Van Aken, J. Gill, M. Scarselli, M. Mora, E. T. Iacobini, C. Brettoni, G. Galli, M. Mariani, F. Vegni, D. Maione, D. Rinaudo, R. Rappuoli, J. L. Telford, D. L. Kasper, G. Grandi, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. Complete genome sequence and comparative genomic analysis of an emerging human pathogen, serotype V Streptococcus agalactiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:12391-12396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Wilder-Smith, E., K. M. Chow, R. Kay, M. Ip, and N. Tee. 2000. Group B streptococcal meningitis in adults: recent increase in Southeast Asia. Aust. N. Z. J. Med. 30:462-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]