Abstract

stx2 genes from 138 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) isolates, of which 127 were of bovine origin (58 serotypes) and 11 of human origin (one serotype; O113:H21), were subtyped. The bovine STEC isolates from Australian cattle carried ehxA and/or eaeA and predominantly possessed stx2-EDL933 (103 of 127; 81.1%) either in combination with stx2vhb (32 of 127; 25.2%) or on its own (52 of 127; 40.4%). Of 22 (90.9%) bovine isolates of serotype O113:H21, a serotype increasingly recovered from patients with hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) or hemorrhagic colitis, 20 contained both stx2-EDL933 and stx2vhb; 2 isolates contained stx2vhb only. Although 7 of 11 (63.6%) human O113:H21 isolates associated with diarrhea possessed stx2-EDL933, the remaining 4 isolates possessed a combination of stx2-EDL933 and stx2vhb. Three of the four were from separate sporadic cases of HUS, and one was from an unknown source.

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) is commonly carried by ruminants (especially cattle) and is an important enteropathogen, causing human diseases ranging from mild diarrhea to more severe conditions such as hemorrhagic colitis (HC) and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) (7, 15, 22a, 25, 28, 47). Although over 150 serotypes of STEC have been associated with human disease (12, 20), serotype O157:H7 is believed to be responsible for the majority of outbreaks and sporadic cases of HUS in the United States, Japan, and Europe. However, non-O157 STEC is of greater significance in Australia (16) and Argentina (35), and its role in HUS and HC in the United States and Europe is gaining recognition (24).

The most critical factors of STEC associated with severe human disease are the Shiga toxins. STEC can produce one or both of these groups of toxins which comprise two immunologically non-cross-reactive groups (designated Stx1 and Stx2), although other virulence factors such as intimin and enterohemolysin either directly contribute to (or are implicated by association with) the pathogenicity of STEC (11, 21).

stx2 comprises 11 distinct variants (5, 19, 23, 31, 38, 39, 42, 45, 46, 50) and is considered the most important STEC virulence factor associated with human disease (11, 21, 34, 41). More importantly, differences in the degree of pathogenicity of STEC serotypes have been associated with variations in the stx2 subtype (27, 29, 30, 42). The most frequently reported stx2 subtypes are represented by stx2c, stx2d, and stx2e (42, 46, 50).

Although more than 200 different O:H serotypes of STEC have been isolated from cattle (1, 7, 12, 20, 24, 49, 51), there is a paucity of information regarding associations between serotype, stx2 subtype, and virulence factor profiles among STEC isolates from meat-producing animals (9, 10, 22a, 26, 33, 43). stx2 subtypes stx2-EDL933 and stx2c (stx2vha and stx2vhb) have been described in European studies of bovine STEC; however, their association with serotype has not been reported previously (8, 42, 46). Ramachandran et al. (44) demonstrated that stx2-containing STEC from ovine feces usually belonged to the stx2d subtypes (stx2d-Ount/O111/OX3a).

The purpose of this study was to subtype stx2 genes among a serologically diverse collection of 138 stx2-containing STEC isolates primarily derived from bovine feces collected from the eastern states of Australia and to compare stx2 subtypes of STEC isolates of serotype O113:H21 (an important serotype increasingly associated with HUS and HC in humans) of bovine and human origin.

A total of 138 STEC isolates, of which 134 were non-O157, were used in this study. These consisted of 127 isolates from cattle and 11 human isolates from individual cases of clinical infections (Table 1). All isolates were prepared and subjected to multiplex PCR for the detection of STEC virulence factors stx1, stx2, ehxA, and eaeA as described previously (14). Amplified PCR products were then resolved by gel electrophoresis through agarose (2% wt/vol) and stained with ethidium bromide (5 μl/ml). Visualization was undertaken using UV illumination, and images were captured using a GelDoc 1000 image analysis station (Bio-Rad).

TABLE 1.

Virulence factor profiles and stx2 subtypes of STEC of bovine and human origin

| Source | Serotype | No. of isolates of animal or human origin | Virulence factor

|

No. of isolates containing stx2 variant(s)

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stx1 | stx2 | ehxA | eaeA | stx2-EDL.933 | stx2vhb | stx2d-Ount | stx2-EDL933/stx2vhb | stx2-EDL933/stx2vhb/stx1 | stx2vhb/stx1 | stx2-EDL933/stx1 | stx2d-OX3a | |||

| Ba | O2:H8 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O3:H7 | 2 | + | + | + | − | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| B | O5:H− | 2 | + | + | + | − | 2 | |||||||

| B | O5:H7 | 2 | + | + | + | − | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| B | O6:H8 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O6:H28 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O6:H34 | 3 | − | + | + | − | 3 | |||||||

| B | O8(KA):H51 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O8:H16 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O8:H19 | 6 | − | + | + | − | 6 | |||||||

| BDb | O21:H21 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O28:H8 | 3 | − | + | + | − | 3 | |||||||

| B, BD | O28:H40 | 2 | − | + | + | − | 2 | |||||||

| B | O49:H− | 1 | − | + | + | + | 1 | |||||||

| B | O53:H2 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O76:H7 | 1 | − | + | + | + | 1 | |||||||

| B | O81:H21 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O82:H8 | 5 | + | + | + | − | 1 | 4 | ||||||

| B | O82:H40 | 2 | + | + | + | − | 2 | |||||||

| B | O91:H− | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O91:H21 | 1 | − | + | + | + | 1 | |||||||

| B | O93:H19 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O104:H7 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O108:H7 | 2 | + | + | + | − | 2 | |||||||

| B | O110:H40 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O111:H− | 1 | − | + | + | + | 1 | |||||||

| B | O111:H− | 1 | + | + | + | + | 1 | |||||||

| BD | O111:H8 | 1 | + | + | + | + | 1 | |||||||

| BD | O113:H− | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B BD | O113:H21 | 20 | − | + | + | − | 20 | |||||||

| B | O113:H21 | 2 | + | + | − | − | 2 | |||||||

| Hc (HUS, HAd) | O113:H21 | 3 | − | + | + | − | 3 | |||||||

| H (Diarrhea, HUS) | O113:H21 | 6 | − | + | + | − | 6 | |||||||

| H (?) | O113:H21 | 1 | − | + | − | − | 1 | |||||||

| H (?) | O113:H21 | 1 | − | + | − | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O116:H21 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O130:H11 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O130:H11 | 6 | − | + | + | − | 6 | |||||||

| B | O130:H38 | 2 | + | + | + | − | 2 | |||||||

| B | O141:H49 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O153:H8 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O153:HR | 2 | + | + | + | − | 2 | |||||||

| B, BD | O157:H8 | 2 | − | + | + | − | 2 | |||||||

| B | O157:H− | 1 | + | + | + | + | 1 | |||||||

| B | O157:H7 | 1 | − | + | + | + | 1 | |||||||

| B | O163:H− | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O163:H19 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | O163:H19 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | Ont:H2 | 2 | − | + | + | − | 2 | |||||||

| B | Ont:H5 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | Ont:H7 | 2 | − | + | + | − | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| B | Ont:H8 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | Ont:H8 | 3 | − | + | + | − | 3 | |||||||

| B | Ont:H11 | 2 | + | + | + | − | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| B | Ont:H11 | 2 | − | + | + | − | 2 | |||||||

| BD | Ont:H11 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | Ont:H16 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | Ont:H21 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | Ont:H28 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | Ont:H28 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | Ont:H30 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | Ont:H41 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | Ont:H49 | 3 | − | + | + | − | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| B | Ont:H49 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | Ont:HR | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | /PICK> | ||||||

| B | OR:H− | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | OR:H3 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | OR:H8 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | OX3:H8 | 5 | − | + | + | − | 5 | |||||||

| B | OX3:H8 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| B | OX3:H21 | 1 | − | + | − | + | 1 | |||||||

| B | OX3:H40 | 1 | − | + | + | − | 1 | |||||||

| Total | 138 | 59 | 8 | 2 | 31 | 5 | 11 | 19 | 3 | |||||

B, feces from healthy cattle unless otherwise specified.

BD, diagnostic fecal samples from cattle.

H, human feces.

HA, hemolytic anemia.

Bovine STEC isolates with stx2 were subjected to subtyping using typing schemes previously reported (4, 42, 48). For this study, stx2d subtypes are defined as nucleotide sequence variants of stx2 (stx2d-Ount, stx2d-O111, and stx2d-OX3a), as described previously (42), and are not the potentially mucin-activatable stx2d variants described by Melton-Celsa et al. (30) (defined as stx2vha and stx2vhb in this study). stx2 genes amplified with VT2-e and VT2-f primers and Lin F and Lin R primers were subjected to restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis with the enzymes HaeIII and PvuII (42) and the enzymes HincII and AccI (28), respectively. In circumstances in which a stx2 gene could not be reliably subtyped using the above-described approach, the gene was amplified with Tyler F and Tyler R primers and subjected to RFLP analysis with the enzymes MspI, NciI, and RsaI (Table 2) (48). PCR products were digested for a minimum of 4 h at 37°C. Fragments were separated by electrophoresis through agarose gels (2% wt/vol), and subtypes were determined according to comparison with profiles reported previously (4, 42, 48).

TABLE 2.

Restriction fragment sizes used for analysis of stx2

| Primers used to amplify fragment | Restriction enzyme | Expected fragment size(s) for:

|

Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stx2-EDL933 | stx2vhb | stx2d-Ount | stx2d-OX3 | |||

| VT2-e, VT2-f | HaeIII | 348 | 216, 132 | 216, 132 | 167, 132, 49a | 42 |

| PvuII | 323, 25a | 250, 73, 25a | 200, 120, 28a | 200, 120, 28a | ||

| Lin F, Lin R | HincII | 555, 262, 62 | 555, 340 | 880, 15a | 880, 15 | 28 |

| AccI | 544, 351 | 544, 351 | 906 | 544, 351 | ||

| Tyler F, Tyler R | MspI | 232, 48a | 108, 73, 51a | 155, 125 | 48 | |

| NciI | 385 | 159, 126 | ||||

| RsaI | 216, 69 | 216, 69 | ||||

Fragment too small to visualize under the electrophoresis conditions used.

DNA sequence analysis of both the A and B subunits of two stx2-containing STEC isolates with serotype O110:H40 and Ont:H11 were undertaken, since RFLP analyses confirmed these isolates possessed stx2 subtypes representative of the majority of the collection. stx2 was amplified using 10 pmol of each of the oligonucleotide primers Stx2F and Stx2R (Table 3). PCRs (50 μl) were carried out containing 2 μl of nucleic acid of a crude whole-cell DNA template prepared using Instagene matrix as described previously (17), 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase.

TABLE 3.

Primer pairs used to amplify stx2

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Size of fragment (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| stx2 typing | |||

| VT2-e | AATACATTATGGGAAAGTAATA | 348 | 42 |

| VT2-f | TAAACTGCACTTCAGCAAAT | ||

| Lin F | GAACGAAATAATTTATATGT | 900a | 28 |

| Lin R | TTTGATTGTTACAGTCAT | ||

| Tyler F | AAGAAGATGTTTATGGCGGT | 285 | 48 |

| Tyler R | CACGAATCAGGTTATGCCTC | ||

| stx2 sequencing | |||

| StxF | TATCTGCGCCGGGTCT | 1,280 | 44 |

| StxR | CAAAKCCKGARCCTGA | ||

| Gannon F | CCATGACAACGGACAGCAGTT | 779 | 18 |

| Gannon R | CCTGTCAACTGAGCAGCACTTTG | ||

| Paton F | GGCACTGTCTGAAACTGCTCC | 255 | 37 |

| Paton R | TCGCCAGTTATCTGACATTCTG | ||

| ST F | AATGCAATGGCGG | 200 | This study |

| Stx2R | CAAATCCGGAGCCTGC | ||

| Stx2F2 | AATCCAGTACAACGCGCCA | 600 | This study |

| ST R | AACGCAGAACTGCTCT | ||

| Tyler F | AAGAAGATGTTTATGGCGGT | 285 | 48 |

| Tyler R | CACGAATCAGGTTATGCCTC | ||

| KBStx2F | AATCCAGTACAACGCGCC | 395 | This study |

| KBStx2R | TTGCTGAATAATCAGACG |

Amplicons differ by a few nucleotides depending on the variant.

Thermocycler steps involved an initial denaturation step (95°C for 5 min) followed by 35 cycles of denaturation (95°C for 30 s), annealing (60°C for 45 s), and extension (72°C for 90 s). A final extension step of 72°C for 5 min completed the PCR. The amplified PCR product was separated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. For DNA sequencing, PCR amplification products were purified using a QIAquick DNA purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Sequencing reactions were performed using the Big Dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction DNA sequencing kit and electrophoresed on an ABI prism 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) as described previously (44). Auto Assembler software (Perkin Elmer) was used to compile and analyze the DNA sequences. Nucleotide and amino acid analysis was performed using programs accessed via the Australian National Genomic Information Service (www.angis.org.au). Sequences were compared with those deposited in public databases using the BlastN and BlastP algorithms (2).

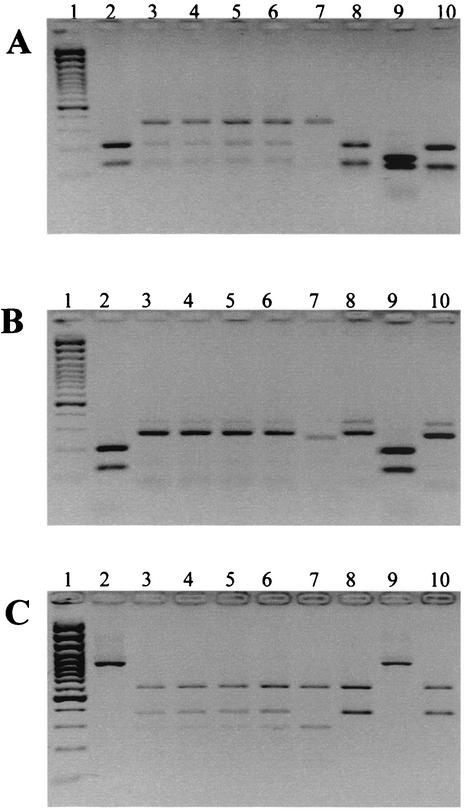

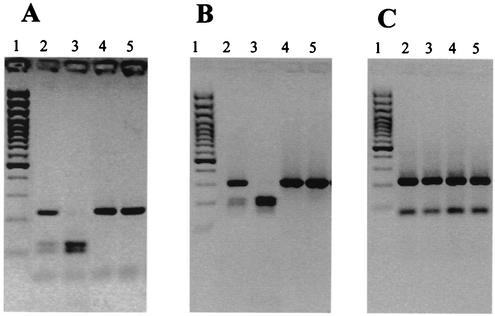

All 138 isolates possessed stx2 and comprised 58 serotypes. STEC serotypes and their virulence factor profiles are listed in Table 1. A significant proportion of bovine STEC isolates (32 of 127; 25.2%) possessed more than one stx2 variant or a combination of an stx2 variant(s) together with stx1 (35 of 127; 27.6%). Isolates with two copies of stx2 were shown to possess stx2-EDL933 and stx2vhb (31 of 127; 24.4%) (Table 1). STEC isolates possessing stx2-EDL933 alone were also prevalent (59 of 138; 42.8%). These 59 isolates belonged to 28 serotypes (Table 4). Isolates with stx2-EDL933 and stx1 comprised the third most common group (19 of 138; 13.7%), representing 13 serotypes, followed by stx2vhb and stx1 (11 of 138; 7.9%), comprising 9 serotypes. STEC possessing the three Shiga toxin factors stx2-EDL933, stx2vhb, and stx1 was identified with a frequency of 5 of 138 (3.6%) and was represented by 5 serotypes (Table 4). STEC containing stx2vhb alone (8 of 138; 5.8%), stx2d-Ount (2 of 138; 1.4%), or stx2d-OX3a (3 of 138; 2.2%) was isolated infrequently (Table 4). Two bovine isolates of the serotype O5:H−, a serotype commonly recovered from ovine feces (14), possessed an stx2d-OX3a subtype; this subtype is commonly associated with ovine STEC (44). Representative RFLP profiles produced by the digestion of PCR amplification products spanning different regions of stx2 are depicted in Fig. 1 and 2. DNA sequence analysis of stx2 derived from STEC serotype O110:H40 showed 99.8% sequence identity with sequences of stx2-EDL933 (accession number Z37725.1) (36) and the p gene derived from phage 933W (13). The two nucleotide polymorphisms that differentiated the stx2 sequence of O110:H40 with stx2-EDL933 did not alter the predicted amino acid sequence. The stx2 gene from an O110:H40 isolate was selected for DNA sequence analysis, because PCR-RFLP analysis indicated that it was indicative of stx2 genes representative of the majority of bovine isolates used in this study (Fig. 1, lane 6). DNA sequence analysis of the stx2 gene amplified from the Ont:H11 isolate showed 99.5% (5 nucleotide polymorphisms in the A subunit) sequence identity with stx2vhb, a sequence variant of stx2c (accession number X61283.1) (31). These data concur with the results of PCR-RFLP analyses used to type stx2 variants in this study. Of the five nucleotide polymorphisms identified in the A-subunit sequence, only two polymorphisms resulted in a change in the amino acid sequence. The B subunit of stx2vhb in Ont:H11 showed nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequences identical to those of stx2vhb (accession number X61283.1) (31).

TABLE 4.

stx2 variant(s) and association with serotype

| stx2 variant(s) | No. (%) of isolatesa | Serotypes |

|---|---|---|

| stx2-EDL933 | 59 (42.8) | O6:H34, O8:(KA):H51, O8:H19, O21:H21, O28:H8, O28:H40, O53:H2, O76:H7, O81:H21, O93:H19, O104:H7, O113:H21, O116:H21, O130:H11, O141:H49, O157:H8, O163:H19, Ont:H2, Ont:H5, Ont:H7, Ont:H8, Ont:H28, Ont:H49, Ont:HR, OR:H3, OX3:H8, OX3:H21, OX3:H40 |

| stx2-EDL933/stx2vhb | 31 (32.6) | O6:H8, O6:H28, O49:H−, O113:H−, O113:H21, Ont:H7, Ont:H49, OR:H8 |

| stx2-EDL933/stx1 | 19 (10.4) | O5:H7, O82:H8, O82:H40, O110:H40, O111:H−, O111:H8, O103:H11, O153:HR, Ont:H11, ONT:H21, Ont:H28, Ont:H30, Ont:H41 |

| stx2vhb/stx1 | 11 (8.0) | O3:H7, O5:H7, O108:H7, O130:H38, O157:H−, O163:H19, Ont:H8, Ont:H11, OX3:8 |

| stx2vhb | 8 (5.8) | O2:H8, O113:H21, O157:H7, Ont:H11, OR:H− |

| stx2-EDL933/stx2vhb/stx1 | 5 (3.6) | O3:H7, O8:H16, O82:H8, O163:H−, Ont:H16 |

| stx2d-OX3a | 3 (2.2) | O5:H−, O91:H21 |

| stx2d-Ount | 2 (1.4) | O91:H−, O153:H8 |

Values are numbers and percentages compared to a total of 138 isolates.

FIG. 1.

HaeIII (A) and PvuII (B) digests of PCR products obtained with VT2-e and VT2-f primers and HincII (C) digests of PCR products obtained with Lin F and Lin R primers. Lanes: 1, 100-bp Plus marker; 2, stx2d-Ount variant of serotype O91:H−; 3, stx2-EDL933/stx2vhb variant of serotype O113:H21; 4, stx2-EDL933/stx2vhb variant of serotype O113:H21; 5, stx2-EDL933/stx2vhb variant of serotype O113:H21; 6, stx2-EDL933/stx2vhb variant of serotype O110:H40; 7, stx2-EDL933 variant of serotype Ont:H5; 8, stx2vhb variant of serotype Ont:HR; 9, stx2-OX3a variant of serotype O5:H−; 10, stx2vhb variant of serotype Ont:H11.

FIG. 2.

MspI (A), NciI (B), and RsaI (C) digests of PCR products obtained with Tyler F and Tyler R primers. Lanes: 1, 100-bp Plus marker; 2, stx2-EDL933/stx2vhb variant of serotype O113:H21; 3, stx2vhb variant of serotype Ont:HR; 4, stx2-EDL933 variant of serotype Ont:H5; 5, stx2-EDL933 variant of serotype Ont:H5.

In this study, we determined the stx2 subtypes of 127 bovine STEC isolates belonging to 58 serotypes and showed that Australian bovine STEC which also possesses ehxA and/or eaeA predominantly possesses either stx2-EDL933 or stx2vhb subtypes (alone or in combination with one another). We also demonstrated that several serotypes, particularly O113:H21, simultaneously possess both these subtypes.

In a recent study of 167 stx2-containing STEC isolates from healthy cattle in France, stx2vhb, stx2-EDL933, and stx2vha subtypes were commonly identified (5). Our study identified stx2-EDL933 and stx2vhb as the predominant subtypes (122 of 127; 96.1%) among Australian bovine STEC isolates; stx2vha-positive STEC isolates were not observed among any of STEC isolates in our study. Although the serotypes belonging to the stx2-containing STEC isolates from France were not reported (5), a recent study of 186 STEC isolates from cattle during a 1-year study in France (43) showed that few isolates possessed serotypes in common with those identified in this study. Our data suggest that stx2vha-positive STEC belongs to serotypes not commonly found in Australian cattle. Alternatively, stx2vha may only be found in STEC isolates that lack the accessory virulence factors ehxA and/or eaeA (termed complex STEC [22]), since all but 4 of the 138 STEC isolates in this study possessed one or both of these factors. In support of the latter hypothesis, the study by Bertin et al. (5) identified enterohemolysin among STEC isolates harboring stx2-EDL933 (78%) or a combination of stx2-EDL933 and stx2vhb (85%); only 6 of 43 (14%) stx2vha-containing isolates also possessed ehxA, and the presence of eaeA was not reported. Furthermore, recent studies in our laboratories have identified stx2vha-containing STEC in isolates that do not possess ehxA and/or eaeA (our unpublished data). STEC isolates simultaneously containing three stx2 variants were not observed among the 138 Australian STEC isolates, unlike the results reported by Bertin et al. (5). Furthermore, the untypeable stx2 variant (identified as stx2-NV206) which comprised 24 of 167 (14.4%) of isolates in the study by Bertin et al. (5) was not observed in our Australian collection; 25% of STEC isolates possessing the stx2-NV206 possessed ehxA (5). Collectively, stx2-subtyping data suggest that different non-O157 STEC populations predominate in Australia and France. However, the fact that 134 of 138 (97.1%) of the Australian stx2-containing STEC isolates and 54 of 130 (41.5%) of the stx2-containing French isolates possessed ehxA and/or eaeA may bias comparisons between these two STEC populations. Further studies are required to validate these hypotheses.

Serotype O113:H21 is increasingly being isolated from patients with HUS (6, 17, 40) and was the most predominant serotype in stx2-containing STEC isolates from healthy cattle in Australia (22a). Studies conducted in France (43), Japan (26), and Spain (9, 10, 33) all indicated that O113:H21 is among the most prevalent STEC serotypes recovered from cattle feces. Furthermore, O113:H21 was identified in 10 of 41 (24.4%) STEC isolates recovered from a Canadian study of naturally contaminated beef (3). All of the O113:H21 isolates recovered in our study (22 bovine and 11 human) were eaeA negative; 29 of 33 (87.9%) possessed the ehxA gene, and only 2 of 33 (6.1%) possessed stx1. Of 22 (90.9%) bovine isolates of serotype O113:H21, 20 concomitantly possessed both stx2-EDL933 and stx2vhb while 2 (9.1%) only possessed stx2vhb. Two O113:H21 isolates recovered from HUS patients and a third isolate from a patient with anemia also simultaneously possessed stx2-EDL933 and stx2vhb. However, four isolates of O113:H21 recovered from human cases of diarrhea, two from patients with HUS, and one isolate from an asymptomatic human individual possessed stx2-EDL933 only. Of the 58 different serotypes identified in our study, 7 serotypes have been reported to cause HUS (O5:H−, O91:H−, O91:H21, O111:H−, O111:H8, O157:H7, and O163:H19).

Ramachandran et al. (44) reported that ovine STEC isolates that also contain ehxA and/or eaeA predominantly possess stx2d (stx2d-Ount, stx2d-OX3a, and stx2dO111) subtypes. In contrast, the cattle STEC isolates described in this study rarely possessed stx2d subtypes (5 of 138; 3.6%) and three of these isolates possessed STEC serotypes (O5:H− and O91:H−) typically found in sheep. Furthermore, none of the ovine isolates examined in the study of Ramachandran et al. (44) contained stx2vhb and only a single isolate possessed stx2EDL933, highlighting a dramatic contrast with results reported in the present study of bovine STEC. Bertin et al. (5) showed that 167 bovine stx2-positive STEC isolates from healthy cattle rarely possessed an stx2d subtype (8.5% of 167), but their serotype(s) was not reported. Beutin et al. (8) also found that with the exception of a single serotype (O90:H24), cattle and sheep differed with respect to the O:H types of their STEC floras. Together, these and other studies (14, 22, 22a, 32) suggest that genetically and serologically different populations of STEC inhabit the gastrointestinal tracts of cattle and sheep.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from the Australian Cooperative Research Centre for Cattle and Beef Quality.

We thank Christine Gillen for technical assistance with sequencing and Kari Gobius for the supply of control DNA preparations containing STEC DNA with the stx2vha Shiga toxin gene.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aleksic, S. 1995. W. H. O. report on Shiga-like toxin producing Escherichia coli (SLTEC), with emphasis on zoonotic aspects. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 2.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atalla, H. N., R. Johnson, S. McEwen, R. W. Usborne, and C. L. Gyles. 2000. Use of a Shiga toxin (Stx)-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and immunoblot for detection and isolation of Stx-producing Escherichia coli from naturally contaminated beef. J. Food Prot. 63:1167-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bastian, S. N., T. Carle, and F. Grimont. 1998. Comparison of 14 PCR systems for the detection and subtyping of stx genes in Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Res. Microbiol. 149:457-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertin, Y., K. Boukhors, N. Pradel, V. Livrelli, and C. Martin. 2001. Stx2 subtyping of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from cattle in France: detection of a new stx2 subtype and correlation with additional virulence factors. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3060-3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bettelheim, K. A. 2001. Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7: a red herring? J. Med. Microbiol. 50:201-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beutin, L., D. Grier, H. Steinruck, S. Zimmermann, and F. Scheutz. 1993. Prevalence and some properties of verotoxin (Shiga-like-toxin)-producing Escherichia coli in seven different species of healthy animals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:2483-2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beutin, L., D. Geier, S. Zimmermann, S. Aleksic, H. A. Gillespie, and T. S. Whittam. 1997. Epidemiological relatedness and clonal types of natural populations of Escherichia coli strains producing Shiga toxins in separate populations of cattle and sheep. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2175-2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanco, M., J. E. Blanco, J. Blanco, E. A. Gonzalez, M. P. Alonso, H. Maas, and W. H. Jansen. 1996. Prevalence and characteristics of human and bovine verotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains isolated in Galicia (north-western Spain). Eur. J. Epidemiol. 12:13-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanco, M., J. E. Blanco, J. Blanco, A. Mora, C. Prado, M. P. Alonso, M. Mourino, C. Madrid, C. Balsalobre, and A. Juarez. 1997. Distribution and characterization of faecal verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) isolated from healthy cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 54:309-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boerlin, P., S. A. McEwen, F. Boerlin-Petzold, J. B. Wilson, R. P. Johnson, and C. L. Gyles. 1999. Associations between virulence factors of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and disease in humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:497-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke, R. C., J. B. Wilson, S. C. Read, S. Renwick, K. Rahn, R. P. Johnson, D. Alves, M. A. Karmali, H. Loir, S. A. McEwen, J. Spika, and C. L. Gyles. 1994. Verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) in the food chain: preharvest and processing perspectives, p. 17-24. In M. A. Karmali and A. G. Goglio (ed.), Recent advances in verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli infections. Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 13.Datz, M., C. Janetzki-Mittmann, S. Franke, F. Gunzer, H. Schmidt, and H. Karch. 1996. Analysis of the enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 DNA region containing lamboid phage gene p and Shiga-like toxin structural genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:791-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Djordjevic, S. P., M. A. Hornitzky, G. Bailey, P. Gill, B. Vanselow, K. Walker, and K. Bettelheim. 2001. Virulence properties and serotypes of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from healthy Australian slaughter-age sheep. J. Clin. Mirobiol. 39:2017-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edelman, R., M. A. Karmali, and P. A. Fleming. 1988. Summary of the international symposium and workshop on infections due to verocytotoxin (Shiga-like toxin)-producing Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 157:1102-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott, E. J., R. M. Robbins-Browne, E. V. O'Loughlin, V. Bennet-Wood, J. Bourke, P. Henning, G. G. Hogg, J. Knight, H. Powell, and D. Redmond. 2001. Nationwide study of haemolytic uremic syndrome: clinical, microbiological, and epidemiological features. Arch. Dis. Child. 85:125-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fagan, P. K., M. A. Hornitzky, K. A. Bettelheim, and S. P. Djordjevic. 1999. Detection of Shiga-like toxin (stx1 and stx2), intimin (eaeA), and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) hemolysin (EHEC hlyA) genes in animal feces by multiplex PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:868-872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gannon, V. P., R. K. King, J. Y. Kim, and E. J. Golsteyn Thomas. 1992. Rapid and sensitive method for detection of Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli in ground beef using the polymerase chain reaction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3809-3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gannon, V. P. J., C. Teerling, S. A. Masri, and C. L. Gyles. 1990. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of another variant of the Escherichia coli Shiga-like toxin II family. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136:1125-1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffin, P. M. 1995. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli, p. 739-758. In M. J. Blaser, P. D. Smith, J. I. Ravdin, H. B. Greenberg, and R. L. Guerrant (ed.), Infections of the gastrointestinal tract. Raven Press, New York, N.Y.

- 21.Gyles, C., R. Johnson, A. Gao, K. Ziebell, D. Pierard, S. Aleksic, and P. Boerlin. 1998. Association of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli hemolysin with serotypes of Shiga-like-toxin-producing Escherichia coli of human and bovine origins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4134-4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hornitzky, M. A., K. A. Bettelheim, and S. P. Djordjevic. 2001. The detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in diagnostic bovine faecal samples using vancomycin-cefimine-cefsulodin blood agar and PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 198:17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22a.Hornitzky, M. A., B. A. Vanselow, K. Walker, B. Corney, P. Gill, G. Bailey, and S. J. Djordjevic. 2002. Virulence properties and serotypes of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from healthy Australian cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6439-6445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ito, H., A. Terai, H. Kurazono, Y. Takeda, and M. Nishibuchi. 1990. Cloning and nucleotide sequencing of Vero toxin 2 variant genes from Escherichia coli O91:H21 isolated from a patient with hemolytic uremic syndrome. Microb. Pathog. 8:47-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson, R. P., R. C. Clarke, J. B. Wilson, S. C. Read, K. Rahn, S. A. Renwick, K. A. Sandhu, D. Alves, M. A. Karmali, H. Loir, S. A. McEwen, J. S. Spika, and C. L. Gyles. 1996. Growing concerns and recent outbreaks involving non-O157:H7 serotypes of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Food Prot. 59:1112-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karmali, M. A., M. Petric, C. Lim, P. C. Fleming, G. S. Arbus, and H. Lior. 1985. The association between idiopathic hemolytic uremic syndrome and infection by verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 151:775-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi, H., J. Shimada, M. Nakazawa, T. Morozumi, T. Pohjanvitra, S. Pelkonnen, and K. Yamamoto. 2001. Prevalence and characteristics of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from healthy cattle in Japan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:484-489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kokai-Kun, J. F., A. R. Melton-Celsa, and A. D. O'Brien. 2000. Elastase in intestinal mucus enhances the cytotoxicity of Shiga toxin type 2d. J. Biol. Chem. 275:3713-3721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin, Z., S. Yamasaki, H. Kurazono, M. Ohmura, T. Karasawa, T. Inoue, S. Sakamoto, T. Suganami, T. Takeoka, Y. Taniguchi, and Y. Takeda. 1993. Cloning and sequencing of two new verotoxin 2 variant genes of Escherichia coli isolated from cases of human and bovine diarrhea. Microbiol. Immunol. 37:451-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindgren, S. W., A. R. Melton, and A. D. O'Brien. 1993. Virulence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O91:H21 clinical isolates in an orally infected mouse model. Infect. Immun. 61:3832-3842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melton-Celsa, A. R., S. C. Darnell, and A. D. O'Brien. 1996. Activation of Shiga-like toxins by mouse and human intestinal mucus correlates with virulence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O91:H21 isolates in orally infected, streptomycin-treated mice. Infect. Immun. 64:1569-1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer, T., H. Karch, J. Hacker, H. Bocklage, and J. Heesemann. 1992. Cloning and sequencing of a Shiga-like toxin II-related gene from Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain 7279. Zentbl. Bacteriol. 276:176-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montenegro, M. A., M. Bulte, T. Trumpf, S. Aleksic, G. Reuter, E. Bulling, and R. Helmuth. 1990. Detection and characterization of fecal verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli from healthy cattle. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:1417-1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orden, J. A., J. A. Ruiz-Santa-Quiteria, D. Cid, S. Garcia, R. Sanz, and R. De la Fuente. 1998. Verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) and eae-positive non-VTEC in 1-30-days-old diarrhoeic dairy calves. Vet. Microbiol. 63:239-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ostroff, S. M., P. I. Tarr, M. A. Neill, J. H. Lewis, N. Hargrett-Bean, and J. M. Kobayashi. 1989. Toxin genotypes and plasmid profiles as determinants of systemic sequelae in Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. J. Infect. Dis. 160:994-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parma, A. E., M. E. Sanz, J. E. Blanco, J. Blanco, M. R. Viñas, M. Blanco, N. L. Padola, and A. I. Etcheverria. 2000. Virulence genotypes and serotypes of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from cattle and foods in Argentina. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 16:757-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paton, A. W., A. J. Bourne, P. A. Manning, and J. C. Paton. 1995. Comparative toxicity and virulence of Escherichia coli clones expressing variant and chimeric Shiga-like toxin type II operons. Infect. Immun. 63:2450-2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paton, A. W., and J. C. Paton. 1998. Detection and characterization of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli using multiplex PCR assays for stx1, stx2, eaeA, enterohemorrhagic E. coli hlyA, rfbO111, and rfbO157. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:598-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paton, A. W., J. C. Paton, P. N. Goldwater, and P. A. Manning. 1993. Direct detection of Escherichia coli Shiga-like toxin genes in primary fecal cultures by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:3063-3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paton, A. W., J. C. Paton, M. W. Heuzenroeder, P. N. Goldwater, and P. A. Manning. 1992. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of a variant Shiga-like toxin II gene from Escherichia coli OX3:H21 isolated from a case of sudden infant death syndrome. Microb. Pathog. 13:225-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paton, A. W., M. Woodrow, R. M. Doyle, J. A. Lanser, and J. C. Paton. 1999. Molecular characterization of a Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli O113:H21 strain lacking eae responsible for a cluster of cases of hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3357-3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pierard, D., G. Cornu, W. Proesmans, A. Dediste, F. Jacobs, J. Vande Walle, A. Mertens, J. Ramet, S. Lauwers, and the Belgian Society for Infectology and Clinical Microbiology HUS Study Group. 1999. Hemolytic uremic syndrome in Belgium: incidence and association with verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli infection. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 5:16-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pierard, D., G. Muyldermans, L. Moriau, D. Stevens, and S. Lauwers. 1998. Identification of new verocytotoxin type 2 variant B-subunit genes in human and animal Escherichia coli isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3317-3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pradel, N., V. Livrelli, C. De Champs, J.-B. Palcoux, A. Reynaud, F. Scheutz, J. Sirot, B. Joly, and C. Forestier. 2000. Prevalence and characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from cattle, food, and children during a one-year prospective study in France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1023-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramachandran, V., M. A. Hornitzky, K. A. Bettelheim, M. J. Walker, and S. P. Djordjevic. 2001. The common ovine Shiga toxin 2-containing Escherichia coli serotypes and human isolates of the same serotypes possess a Stx2d toxin type. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1932-1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt, H., J. Scheef, S. Morabito, A. Caprioli, L. H. Wieler, and H. Karch. 2000. A new Shiga toxin 2 variant (Stx2f) from Escherichia coli isolated from pigeons. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1205-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmitt, C. K., M. L. McKee, and A. D. O'Brien. 1991. Two copies of Shiga-like toxin II-related genes common in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli strains are responsible for the antigenic heterogeneity of the O157:H− strain E32511. Infect. Immun. 59:1065-1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith, H. R., and S. M. Scotland. 1988. Vero cytotoxin-producing strains of Escherichia coli. J. Med. Microbiol. 26:77-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tyler, S. D., W. M. Johnson, H. Loir, G. Wang, and K. R. Rozee. 1991. Identification of verotoxin type 2 variant B subunit genes in Escherichia coli by the polymerase chain reaction and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:1339-1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weiler, L. H., E. Vieler, C. Erpenstein, T. Schlapp, H. Steinruck, R. Bauerfeind, A. Byomi, and G. Baljer. 1996. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains from bovines: association of adhesion with carriage of eae and other genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2980-2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weinstein, D. L., M. P. Jackson, J. E. Samuel, R. K. Holmes, and A. D. O'Brien. 1988. Cloning and sequencing of a Shiga-like toxin type II variant from an Escherichia coli strain responsible for edema disease of swine. J. Bacteriol. 170:4223-4230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willshaw, G. A., S. M. Scotland, H. R. Smith, and B. Rowe. 1992. Properties of vero cytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli of human origin of O serogroups other than O157. J. Infect. Dis. 166:797-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]