Abstract

Amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLPs) were used to characterize the genotypic diversity of a total of 114 Gallibacterium anatis isolates originating from a reference collection representing 15 biovars from four countries and isolates obtained from tracheal and cloacal swab samples of chickens from an organic, egg-producing flock and a layer parent flock. A subset of strains was also characterized by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and biotyping. The organic flock isolates were characterized by more than 94% genetic similarity, indicating that only a single clone was apparent in the flock. The layer parent flock isolates were grouped into two subclusters, each with similarity above 90%. One subcluster contained only tracheal isolates, while the other primarily included cloacal isolates. In conclusion, we show that AFLP analysis enables fingerprinting of G. anatis, which seems to have a clonal population structure within natural populations. There was further evidence of clonal lineages, which may have adapted to different sites within the same animal.

Gallibacterium has recently been established as a new genus in the family Pasteurellaceae (8). The new genus comprises bacteria previously reported as [Actinobacillus] salpingitidis, avian [Pasteurella] haemolytica-like organisms, and [Pasteurella] anatis and contains at least two new species: Gallibacterium anatis and Gallibacterium genomospecies. Gallibacterium was found to be prevalent in the upper respiratory tracts and the lower genital tracts of healthy chickens (3, 7a, 10, 22). However, Gallibacterium isolates have also been recovered in pure culture from a range of pathological lesions in chickens, including lesions from chickens with septicemia, oophoritis, follicle degeneration, salpingitis with or without peritonitis, peritonitis, enteritis, and diseases of the respiratory tract (4, 5, 10, 12, 16, 17, 20, 22, 36, 37). In addition, Mirle et al. (17) suggested that Gallibacterium may be implicated in salpingitis with or without peritonitis, as it was found that it was one of the most common single-bacterium infection-associated lesions in the egg-laying apparatus in chicken examined in a postmortem investigation that included 496 hens. Previous attempts to assess the pathogenic potential of Gallibacterium have indicated that different strains have highly different levels of virulence (3, 10, 16, 22). Characterization of Gallibacterium for epidemiological purposes has, so far, relied on phenotypic characterization (2), which does not normally allow evaluation of clonal diversity or tracing of a particular clonal type (27); thus, the need for a more discriminative typing method is evident. Genotypic methods involving a whole-genome approach have been widely used for these purposes with other bacteria (7, 29). Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) fingerprinting represent highly reproducible and discriminatory genotyping methods that allow the identification of clonal lineages in bacterial populations (38, 40).

The aim of the present study was to provide a discriminative molecular typing method based on AFLP analysis for the differentiation of Gallibacterium isolates of various origins in order to evaluate the genetic diversity of Gallibacterium in natural populations and to enable identification of possible pathogenic clones.

Bacterial strains and production systems.

A total of 114 bacterial strains, including 39 reference strains from four countries representing 15 presently available biovars out of 24 biovars reported (M. Bisgaard, unpublished results), were studied. The reference strains originated from diseased and healthy animals. The remaining 75 isolates were obtained from tracheal and cloacal swab samples of chickens randomly selected from an organic, egg-producing flock as well as from a flock of layer parent chickens.

Phenotypic characterization.

All 39 reference strains and 26 randomly selected isolates from the 75 flock isolates were characterized by using 82 phenotypic characters as previously described by Bisgaard (2). The remaining flock isolates were characterized as G. anatis based on their characteristic colony morphology, including strong β-hemolysis (8). All 26 flock isolates subjected to extensive phenotypic characterization were classified as G. anatis biovar 4.

Genotyping by PFGE.

Genomic DNA was prepared by using an Easy-DNA kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

PFGE analysis included 19 reference strains. SalI and XhoI were used for digestion of DNA, and PFGE was carried out as described by Ojeniyi et al. (26). All 19 reference strains included in the PFGE analysis were found to be unrelated since no common fragments were demonstrated (data not shown).

DNA fingerprinting of avian Gallibacterium strains by AFLP analysis.

AFLP analysis was essentially performed as described by Kokotovic et al. (13). A nonselective BglII primer (carboxyfluorescein; 5′ GAGTACACTGTCGATCT 3′) and the nonselective BspDI primer (5′ GTGTACTCTAGTCCGAT 3′) were used in this study. All AFLP reactions were repeated at least twice to allow evaluation of the reproducibility of the method.

Amplification products were detected on an ABI 377 automated sequencer (PE Biosystems). Each lane included an internal-lane size standard labeled with carboxy-X-rhodamine dye (Applied Biosystems), and GeneScan 3.1 fragment analysis software (Applied Biosystems) was used for fragment size determination and pattern analysis. AFLP profiles comprising fragments in the size range of 75 to 500 bp were considered for numerical analysis with the Bionumerics 2.0 program (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). Normalized AFLP fingerprints were compared by using the Dice similarity coefficient, and clustering analysis was performed by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages. The AFLP fingerprints consisted of 29 to 53 fragments. The reproducibility was found to be 97.5% (standard deviation, ±2.1%). The similarity cutoff level for individual clonal types was 90%.

Genetic diversity of epidemiologically independent strains.

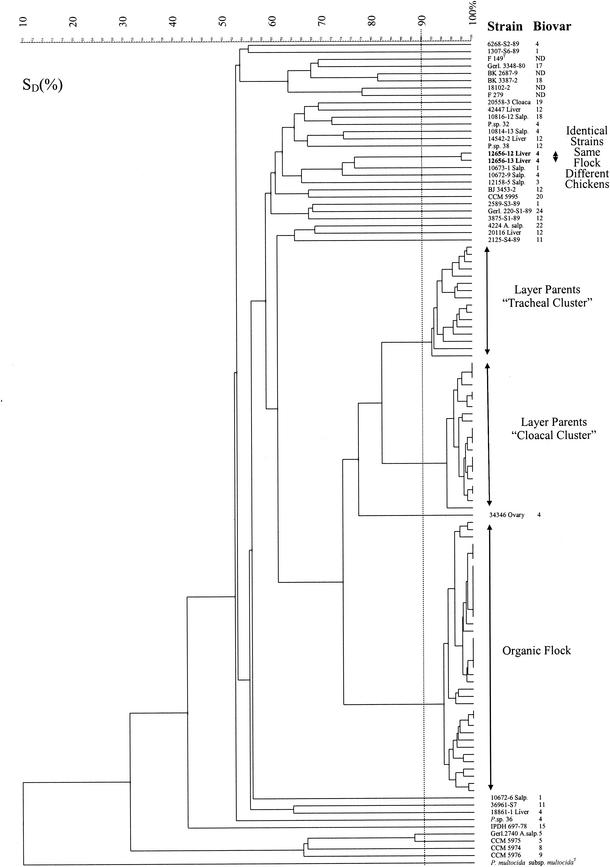

Strains previously classified as [P.] anatis (F 149T, BK 2687-9, 18102-2, and F 279) formed a distinct cluster including two strains, Gerl.3348-80 and BK 3387-2, which were isolated from a goose and a cow, respectively (Fig. 1). Strains 12656-12 Liver and 12656-13 Liver clustered at a similarity level of 98.0%. These strains were obtained from the same flock but were isolated from two individual diseased chickens. Two other strains obtained from diseased chickens from another flock (10672-6 Salp. and 10672-9 Salp.), however, were not closely related. The remaining 26 reference strains did not form well-defined clusters, underlining their epidemiological independence.

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram (unweighted pair group method using arithmetic averages) of AFLP similarities of 114 Gallibacterium strains. SD(%), band-based Dice similarity coefficient expressed as a percentage. The dashed vertical line indicates the 90% similarity level between isolates. ND, not determined; P.sp., [Pasteurella] sp.

Genetic diversity of strains from natural populations.

Strains originating from the organic flock included 18 tracheal isolates and 20 cloacal isolates, which formed a cluster with a similarity level above 94%. These strains could not be separated based on the anatomical site of isolation in the birds, indicating that only one bacterial clone had colonized the organic flock. Strains originating from the layer parent flock also formed a separate cluster. However, this cluster could be separated further into two subclusters. Subcluster I exclusively consisted of tracheal isolates (n = 16), while subcluster II comprised 15 cloacal and 6 tracheal isolates. Subclusters I and II formed a common cluster at 82% similarity (Fig. 1), indicating that two closely related clonal lineages each had colonized a distinct ecological niche within the same bird. All flock isolates and reference strain 34346 Ovary had a common root.

AFLP typing of Gallibacterium isolates.

At present the only methods to conduct epidemiological investigations of Gallibacterium involve case descriptions and thorough phenotypic characterization. There are indications of considerable heterogeneity among strains of Gallibacterium at the phenotypic level, which is why this method is less useful for the purpose of epidemiological investigation. AFLP typing was used in the present study since it has been proven to represent a highly discriminatory and reproducible genotyping method (35, 40). Savelkoul et al. (35) found that Klebsiella strains with a 90 to 100% fingerprint homology could be considered as belonging to the same clone. Other studies of Acinetobacter (11), Campylobacter (28), and Xanthomonas (30) spp. have used a similar homology cutoff value for a single clone, which is why we considered strains with similarity above 90% identical.

The AFLP fingerprints used in the present study consisted of a relatively low number of fragments (29 to 53) compared to the numbers used in other AFLP experiments (13, 28). The low number of fragments may have created the risk of lowering the discriminatory power as a restriction enzyme combination with a higher cutting frequency may have enhanced the chance of detecting more chromosomal mutations, leading to other fragment patterns. However, 18 of the reference strains were also typed by PFGE, and since the AFLP fingerprints discriminated these strains at a level comparable to that of the PFGE method, we regarded the AFLP protocol as sufficiently discriminative. The AFLP analysis showed that the five reference strains CCM 5974, CCM 5975, CCM 5976, Gerl.2740 A.salp., and IPDH 697-78 were characterized by a substantial diversity compared to that of the rest of the strains. This finding is in accordance with the findings shown with 16S rRNA similarity analyses by Christensen et al. (8). In conclusion, we find the present AFLP protocol to be a strong molecular typing tool whose results show good correlation to those of both high- and low-resolution typing techniques. All flock isolates were biotyped as biovar 4, indicating some agreement between the present phenotyping and genotyping methods but underlining the discriminatory inadequacy of biotyping for detailed epidemiological studies.

The finding of only one clonal type in the organic flock was rather surprising given the assumption that low versus high biosecurity would increase the risk of having a number of clones introduced compared to the number of clones in the parent flock. The existence of clonal populations of Gallibacterium at the flock level and indications of specific clonal lineages within the same animal indicate an ongoing genetic diversification and survival of the best-fitted clone on the animal level as well as on the flock level. Clonal diversity in natural populations has been investigated only for a few other members of the bacterial family Pasteurellaceae. Haemophilus influenzae (23, 24, 34, 39), Pasteurella multocida (1, 6, 9), and Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (15, 18, 25, 33) have been found to exhibit a clonal structure in natural populations. The background for the high genetic similarity of Gallibacterium isolates remains to be investigated.

The presence of two clonal lineages within the same animals restricted to either the cloaca or the trachea seems to indicate niche-adapted genotypes originating from a common ancestor from which they can be assumed to have evolved by a series of microevolutionary events leading to the present clusters of closely related clones (19). Previous studies have shown that genetically diverging populations of the same organisms can evolve rapidly from a single clone due to different ecological opportunities (31, 32). The basis for diversification of the Gallibacterium population is unknown; however, small chromosomal differences (e.g., coding for adhesion factors) may provide the basis for the observed niche adaptation, as was shown for Escherichia coli (14, 21). Strains 12656-12 Liver and 12656-13 Liver were found to represent identical clonal types. These strains were isolated from two chickens of the same flock, both suffering from septicemia, indicating that this clone likely possesses a high pathogenic potential or that the individuals were somewhat immunosuppressed.

In conclusion, the results of the present investigation show that the AFLP typing method is useful for distinguishing individual but closely related clones, thereby enabling recognition of specific pathogenic clonal lineages. The method allows for easily interpretable molecular epidemiological analyses and may serve as a strong tool for gaining further insight into the poorly described nature of Gallibacterium.

Acknowledgments

We thank Katja Kristensen for excellent technical assistance.

The Danish Agricultural and Veterinary Research Council financed this work (grant no. 9702797).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aalbaek, B., L. Eriksen, R. B. Rimler, P. S. Leifsson, A. Basse, T. Christiansen, and E. Eriksen. 1999. Typing of Pasteurella multocida from haemorrhagic septicaemia in Danish fallow deer (Dama dama). APMIS 107:913-920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bisgaard, M. 1982. Isolation and characterization of some previously unreported taxa from poultry with phenotypical characters related to Actinobacillus- and Pasteurella species. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand. Sect. B 90:59-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisgaard, M. 1977. Incidence of Pasteurella haemolytica in the respiratory tract of apparently healthy chickens and chickens with infectious bronchitis. Characterisation of 213 strains. Avian Pathol. 6:285-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisgaard, M. 1993. Ecology and significance of Pasteurellaceae in animals. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 279:7-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bisgaard, M., and A. Dam. 1981. Salpingitis in poultry. II. Prevalence, bacteriology, and possible pathogenesis in egg-laying chickens. Nord. Vetmed. 33:81-89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackall, P. J., N. Fegan, G. T. Chew, and D. J. Hampson. 1998. Population structure and diversity of avian isolates of Pasteurella multocida from Australia. Microbiology 144:279-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boerlin, P., H. H. Siegrist, A. P. Burnens, P. Kuhnert, P. Mendez, G. Prétat, R. Lienhard, and J. Nicolet. 2000. Molecular identification and epidemiological tracing of Pasteurella multocida meningitis in a baby. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1235-1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Bojesen, A. M., S. S. Nielsen, and M. Bisgaard. Prevalence and transmission of haemolytic Gallibacterium species in chicken production systems with different biosecurity levels. Avian Pathol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Christensen, H., M. Bisgaard, A. M. Bojesen, R. Mutters, and J. E. Olsen. 2003. Genetic relationships among avian isolates classified as Pasteurella haemolytica, ‘Actinobacillus salpingitidis’ or Pasteurella anatis with proposal of Gallibacterium anatis gen. nov., comb. nov. and description of additional genomospecies within Gallibacterium gen. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:275-287. (First published 6 December 2002; http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.02330-0.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen, J. P., H. H. Dietz, and M. Bisgaard. 1998. Phenotypic and genotypic characters of isolates of Pasteurella multocida obtained from back-yard poultry and from two outbreaks of avian cholera in avifauna in Denmark. Avian Pathol. 27:373-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerlach, H. 1977. Significance of Pasteurella haemolytica in poultry. Prakt. Tierarzt 58:324-328. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janssen, P., K. Maquelin, R. Coopman, I. Tjernberg, P. Bouvet, K. Kersters, and L. Dijkshoorn. 1997. Discrimination of Acinetobacter genomic species by AFLP fingerprinting. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:1179-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohlert, R. 1968. Studies on the etiology of inflammation of the oviduct in the hen. Monatsh. Vetmed. 23:392-395. (In German.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kokotovic, B., G. Bolske, P. Ahrens, and K. Johansson. 2000. Genomic variations of Mycoplasma capricolum subsp. capripneumoniae detected by amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 184:63-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langermann, S., S. Palaszynski, M. Barnhart, G. Auguste, J. S. Pinkner, J. Burlein, P. Barren, S. Koenig, S. Leath, C. H. Jones, and S. J. Hultgren. 1997. Prevention of mucosal Escherichia coli infection by FimH-adhesin-based systemic vaccination. Science 276:607-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacInnes, J. I., J. D. Borr, M. Massoudi, and S. Rosendal. 1990. Analysis of southern Ontario Actinobacillus (Haemophilus) pleuropneumoniae isolates by restriction endonuclease fingerprinting. Can. J. Vet. Res. 54:244-250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthes, S., and J. Hanschke. 1977. Experimentelle Untersuchrungen zur Übertragung von Bakterien über das Hühnerei. Berl. Muench. Tieraerztl. Wochenschr. 90:200-203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mirle, C., M. Schongarten, H. Meinhart, and U. Olm. 1991. Studies into the incidence of Pasteurella haemolytica infections and their relevance to hens, with particular reference to diseases of the egg-laying apparatus. Monatsh. Vetmed. 45:545-549. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Møller, K., R. Nielsen, L. V. Andersen, and M. Kilian. 1992. Clonal analysis of the Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae population in a geographically restricted area by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:623-627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moxon, E. R., P. B. Rainey, M. A. Nowak, and R. E. Lenski. 1994. Adaptive evolution of highly mutable loci in pathogenic bacteria. Curr. Biol. 4:24-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mráz, O., P. Vladík, and J. Bohácek. 1976. Actinobacilli in domestic fowl. Zentbl. Bakteriol. Orig. A 236:294-307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulvey, M. A., J. D. Schilling, and S. J. Hultgren. 2001. Establishment of a persistent Escherichia coli reservoir during the acute phase of a bladder infection. Infect. Immun. 69:4572-4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mushin, R., Y. Weisman, and N. Singer. 1980. Pasteurella haemolytica found in respiratory tract of fowl. Avian Dis. 24:162-168. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Musser, J. M., D. M. Granoff, P. E. Pattison, and R. K. Selander. 1985. A population genetic framework for the study of invasive diseases caused by serotype b strains of Haemophilus influenzae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:5078-5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musser, J. M., J. S. Kroll, E. R. Moxon, and R. K. Selander. 1988. Evolutionary genetics of the encapsulated strains of Haemophilus influenzae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:7758-7762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Musser, J. M., V. J. Rapp, and R. K. Selander. 1987. Clonal diversity in Haemophilus pleuropneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 55:1207-1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ojeniyi, B., N. Høiby, and V. T. Rosdahl. 1991. Genome fingerprinting as a typing method used on polyagglutinable Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. APMIS 99:492-498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsen, J. E., D. J. Brown, M. N. Skov, and J. P. Christensen. 1993. Bacterial typing methods suitable for epidemiological analysis—applications in investigations of salmonellosis among livestock. Vet. Q. 15:125-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.On, S. L., and C. S. Harrington. 2000. Identification of taxonomic and epidemiological relationships among Campylobacter species by numerical analysis of AFLP profiles. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 193:161-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quentin, R., H. Huet, F.-S. Wang, P. Geslin, A. Goudeau, and R. K. Selander. 1995. Characterization of Streptococcus agalactiae strains by multilocus enzyme genotype and serotype: identification of multiple virulent clone families that cause invasive neonatal disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2576-2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rademaker, J. L., B. Hoste, F. J. Louws, K. Kersters, J. Swings, L. Vauterin, P. Vauterin, and F. J. de Bruijn. 2000. Comparison of AFLP and rep-PCR genomic fingerprinting with DNA-DNA homology studies: Xanthomonas as a model system. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 50:665-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rainey, P. B., E. R. Moxon, and I. P. Thomphson. 1993. Intraclonal polymorphism in bacteria, p. 263-300. In J. Gwynfryn Jones (ed.), Advances in microbial ecology. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 32.Rainey, P. B., and M. Travisano. 1998. Adaptive radiation in a heterogeneous environment. Nature 394:69-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rapp, V. J., R. S. Munson, Jr., and R. F. Ross. 1986. Outer membrane protein profiles of Haemophilus pleuropneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 52:414-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saito, M., K. Okada, K. Takemori, and S. I. Yoshida. 2000. Clonal spread of an invasive strain of Haemophilus influenzae type b among nursery contacts accompanied by a high carriage rate of non-disease-associated strains. J. Med. Microbiol. 49:845-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savelkoul, P. H. M., H. J. M. Aarts, J. de Haas, L. Dijkshoorn, B. Duim, M. Otsen, J. L. W. Rademaker, L. Schouls, and J. A. Lenstra. 1999. Amplified-fragment length polymorphism analysis: the state of an art. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3083-3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw, D. P., D. B. Cook, K. Maheswaran, C. J. Lindeman, and D. A. Halvorson. 1990. Pasteurella haemolytica as a co-pathogen in pullets and laying hens. Avian Dis. 34:1005-1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki, T., A. Ikeda, J. Shimada, Y. Yanagawa, M. Nakazawa, and T. Sawada. 1996. Isolation of “Actinobacillus salpingitidis”/avian Pasteurella haemolytica-like isolate from diseased chickens. J. Jpn. Vet. Med. Assoc. 49:800-804. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Urwin, G., J. M. Musser, and M. F. Yuan. 1995. Clonal analysis of Haemophilus influenzae type b isolates in the United Kingdom. J. Med. Microbiol. 43:45-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vos, P., R. Hogers, M. Bleeker, M. Reijans, T. van de Lee, M. Hornes, A. Frijters, J. Pot, J. Peleman, M. Kuiper, et al. 1995. AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:4407-4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]