Abstract

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, plasmid profiling, and phage typing were used to characterize and determine possible genetic relationships between 48 Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica isolates of pig origin collected in Catalonia, Spain, from 1998 to 2000. The strains were grouped into 23 multidrug-resistant fljB-lacking S. enterica serovar 4,5,12:i:− isolates, 24 S. enterica serovar Typhimurium isolates, and 1 S. enterica serovar 4,5,12:−:− isolate. After combining the XbaI and BlnI macrorestriction profiles (XB profile), we observed 29 distinct subtypes which were grouped into seven main patterns. All 23 of the 4,5,12:i:− serovar strains and 10 serovar Typhimurium isolates were found to have pattern AR, and similarities of >78% were detected among the subtypes. Three of the serovar Typhimurium DT U302 strains (strains T3, T4, and T8) were included in the same 4,5,12:i:− serovar cluster and shared a plasmid profile (profile I) and a pattern of multidrug resistance (resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfonamide, tetracycline, gentamicin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) commonly found in monophasic isolates. This led us to the conclusion that strains of the S. enterica 4,5,12:i:− serovar might have originated from an S. enterica serovar Typhimurium DT U302 strain.

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium is one of the main causes of salmonellosis worldwide. In the mid-1980s a new serovar Typhimurium phage type named DT104, characterized by a pattern of resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfonamide, and tetracycline (R-ACSSuT), emerged and was soon reported in many countries, causing considerable concern (4).

At present, serovar Typhimurium is the second most frequent type of Salmonella isolated from human, food, and animal samples in Spain (13, 22). The majority of these isolates correspond to phage types DT104, DT104b and DT U302 (20, 21, 22, 23). In 1997, the Spanish National Reference Laboratory for Salmonella first reported on the emergence of a new Salmonella serovar with the antigenic formula 4,5,12:i:−, which ranks fourth among the Salmonella serovars that are the most frequently isolated in Spain. Interestingly, serovar 4,5,12:i:− has become the most frequently encountered serovar in swine and the second most frequently encountered serovar in pork products (22), a fact that led to the assumption that pigs are the reservoir of such a serovar (5).

The 4,5,12:i:− strains lack the second-phase flagellar antigen encoded by the fljB gene, and it has been suggested that they could be a monophasic variant of either serovar Typhimurium (4,5,12:i:1,2) or serovar Lagos (4,5,12:i:1,5) (6). Echeita et al. (6) also showed that certain 4,5,12:i:− strains that are lysed by phage type 10 (DT U302) and that have the multiresistance profile R-ACSSuT, as well as resistance to gentamicin andtrimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (R-ACSSuT-GSxT) (7, 9) were monophasic variants of serovar Typhimurium.

The rapid increase in the frequency of occurrence of serovar 4,5,12:i:− has made necessary further studies in order to determine its origin and its genetic relationship with other serovars. A wide range of genotypic methods can be used for this purpose; among these is pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), a method used because of its high discriminatory power and easy reproducibility (10, 11, 15, 24).

In this paper we present the results of a genetic comparison of serovar Typhimurium and 4,5,12:i:− isolates of pig origin by bacteriophage typing, PFGE, and plasmid profiling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Twenty-four Salmonella serovar Typhimurium isolates, 23 Salmonella serovar 4,5,12:i:− isolates, and 1 Salmonella 4,5,12:−:− isolate obtained from pig samples from 1998 to 2000 were used in this study.

The serovar Typhimurium isolates were randomly chosen from cultures stored in our laboratory. The 4,5,12:i:− and 4,5,12:− isolates corresponded to the first strains of this type to be isolated during the period of time mentioned above. All isolates originated from Salmonella outbreaks or healthy carriers on different Spanish pig farms. Salmonella serovar Typhimurium LT2 was used as the reference strain.

Serotyping and phage typing.

The serotypes and phage types were determined in the Laboratorio de Sanidad Animal (Algete, Madrid) by the Kauffman-White scheme (14) and as described by Callow (3) and Anderson et al. (1), respectively.

Genomic DNA isolation by PFGE and enzyme restriction.

Bacterial genomic DNA was isolated by the method described by Smith et al. (18), with some minor modifications. A single isolated colony was inoculated into 25 ml of brain heart infusion broth overnight at 37°C. The resulting cell concentration was counted in a Neubauer hemocytometer chamber and was standardized to approximately 6.05 × 107 cells/ml. Twenty milliliters of the broth culture was centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The resulting pellet was washed two more times under the same conditions in 10 ml of PETT IV buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 M NaCl [7.5 pH]) and was finally suspended in 1.5 ml of the same buffer.

Agarose plugs were obtained by mixing 100 μl of the bacterial suspension, 200 μl of PETT IV buffer, and 300 μl of 1.6% low-melting-point agarose (Bio-Rad Laboratories) at 56°C. The plugs were incubated overnight in EC-lysis buffer (6 mM Tris, 1 M NaCl, 100 mM EDTA, 0.2% deoxycholate, 0.5% N-lauryl-sarcosine, 5 mg of lysozyme [Boehringer Mannheim] per ml, and 10 mg of RNase [Gibco BRL] per ml adjusted to pH 7.5) at 37°C. The plugs were then incubated with ESP buffer (0.5 M EDTA, 1% N-lauryl-sarcosine, 0.5 mg of proteinase K per ml [pH 9.5]) for 48 h at 50°C. In the last step, the inserts were washed with TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 0.1 mM EDTA [pH 8]) for 24 h at 4°C while being subjected to subtle agitation and approximately six buffer changes. The plugs were then stored in TE buffer at 4°C until use.

Enzymatic restriction was carried out with one-third of the resulting plugs in an Eppendorf tube with 25 U of XbaI (12) or 10 U of BlnI (25) in 200 μl of H enzymatic buffer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) for 4 h at 37°C.

PFGE.

PFGE was performed with a CHEF DRII (Bio-Rad Laboratories) contour-clamped homogeneous electric field apparatus. Electrophoresis were done in 1% agarose gels (Boehringer Mannheim) in 0.5% TBE buffer (45 mM Tris, 45 mM boric acid, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8]) at 14°C. A constant voltage of 200 V (6 V cm−1) was applied for 26 h, with pulse times ramping initially from 5 to 15 s over 7 h and then from 15 to 60 s over 19 h, as described before for Salmonella (8). A bacteriophage lambda Ladder PFG Marker (New England BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.) was used as the molecular size marker. After ethidium bromide staining, the gels were scanned and analyzed with Diversity Database software (Bio-Rad).

The relationship between different PFGE profiles was analyzed according to the criteria established by Tenover et al. (19), with minor modifications. The method assigns profiles into categories of genetic and epidemiological relatedness. Accordingly, the most common restriction pattern among related isolates was assigned a capital letter code with subindex (subscript) 0. All closely related patterns (three different fragments or less) or possibly related patterns (more than three and less than or equal to six different fragments) were assigned the same letter code with a different subindex. Isolates whose profiles differed from the first profile by seven or more fragments were assigned a new letter. The restriction analysis profiles obtained with each enzyme alone were combined (XbaI-BlnI) and resulted in the XB profile (2, 17). Clustering analysis between PFGE patterns was performed by using Dice's similarity coefficient and the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA) in order to quantify profile similarity relationships by using the software mentioned above.

Plasmid profiles.

Plasmids were obtained with a commercial rapid plasmid purification system (Gibco BRL) consisting of a modified alkaline-sodium dodecyl sulfate procedure. After initial plasmid purification with 3 ml of an overnight culture in Luria-Bertani broth, the plasmid DNA was resolved by electrophoresis in 0.8% agarose.

During computer analysis with the Diversity Database software, the linear molecular weight standard (bacteriophage λ DNA digested with HindIII) for closed circular plasmid molecules was used only as a positional standard for the plasmid profiles, not for molecular weight determination.

RESULTS

Phage typing and antimicrobial resistance.

Phage typing of the 23 serovar 4,5,12:i:− isolates classified 16 of them as U302 (approximately 70%), 5 as nontypeable, 1 as PT193, and 1 as PT208. The 4,5,12:−:− isolate was untypeable. The distribution of the phage types among the Salmonella serovar Typhimurium isolates was six phage type DT104b isolates, five phage type DT U302 isolates, two phage type DT104 isolates, one phage type PT193 isolate, and one phage type PT208 isolate. Nine isolates were untypeable with the available phage library (Table 1). Statistical analysis of these distributions showed that the frequency of the U302 phage type was significantly higher among 4,5,12:i:− isolates (P < 0.001). All monophasic isolates and all but three serovar Typhimurium isolates had the characteristic R-ACSSuT profile. In addition, 16 monophasic isolates (11 phage type DT U302 isolates, 4 nontypeable isolates, and 1 phage type PT193 isolate) had an extended resistance spectrum that included resistance sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim and gentamicin. This extended resistance was also observed in three serovar Typhimurium isolates belonging to the U302 phage type (isolates T3, T4, and T8).

TABLE 1.

Phage types, antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, PFGE profiles, and plasmid profiles of S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar 4,5,12:i:− and Typhimurium isolates included in this study

| Year and isolate iden- tificationa | Phage type | Antimicrobial susceptibilityb | PFGE profile

|

Plasmid profile | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XbaI | BlnI | Combined XB profile | ||||

| 1999 | ||||||

| M1 | U302 | 1 | A4 | R1 | AR6 | I |

| M2 | U302 | 2 | A3 | R5 | AR7 | I |

| M3 | U302 | 2 | A1 | R1 | AR2 | I |

| M4 | NTc | 2 | A10 | R0 | AR0 | VI |

| 2000 | ||||||

| M5 | U302 | 1 | A10 | R0 | AR0 | I |

| M6 | U302 | 2 | A1 | R1 | AR2 | II |

| M7 | U302 | 2 | A8 | R5 | AR13 | I |

| M8 | U302 | 1 | A1 | R1 | AR2 | I |

| M9 | U302 | 1 | A10 | R0 | AR0 | I |

| M10 | NT | 1 | A7 | R2 | AR9 | VII |

| M11 | NT | 2 | A1 | R1 | AR2 | IV |

| M12 | 208 | 1 | A7 | R5 | AR10 | I |

| M13 | U302 | 2 | A11 | R0 | AR12 | I |

| M14 | U302 | 2 | A5 | R1 | AR0 | III |

| M15 | U302 | 2 | A3 | R0 | AR4 | V |

| M16 | U302 | 2 | A5 | R0 | AR0 | VIII |

| M17 | NT | 2 | A13 | R6 | AR8 | I |

| M18 | 193 | 2 | A5 | R3 | AR0 | I |

| M19 | U302 | 2 | A3 | R0 | AR4 | V |

| M20 | U302 | 2 | A10 | R0 | AR0 | V |

| M21 | NT | 2 | A6 | R1 | AR1 | I |

| M22 | U302 | 2 | A9 | R5 | AR11 | I |

| M23 | U302 | 1 | A9 | R5 | AR11 | I |

| M24 | NT | 1 | C4 | T0 | CT0 | XII |

| 1998 | ||||||

| T1 | NT | 1 | B1 | T0 | BT0 | X |

| T2 | 104b | 1 | C3 | T4 | CT1 | —d |

| T3 | U302 | 2 | A2 | R1 | AR5 | I |

| T4 | U302 | 2 | A3 | R5 | AR7 | I |

| T5 | 104 | 1 | A0 | R7 | AR14 | — |

| T6 | 104 | 1 | A0 | R8 | AR14 | XI |

| T7 | NT | 1 | A17 | T1 | AT1 | XVII |

| 1999 | ||||||

| T8 | U302 | 2 | A14 | R0 | AR3 | I |

| T9 | U302 | 1 | A0 | R7 | AR14 | IX |

| T10 | 208 | 1 | A16 | V1 | AV0 | XVII |

| T11 | NT | 1 | A0 | R7 | AR14 | — |

| 2000 | ||||||

| T12 | NT | 1 | A10 | T0 | AT0 | X |

| T13 | 193 | 3 | B0 | V1 | BV1 | XIV |

| T14 | NT | 3 | B0 | V0 | BV0 | XIV |

| T15 | NT | 3 | B0 | V0 | BV0 | XIV |

| T16 | 104b | 1 | B1 | T2 | BT1 | — |

| T17 | 104b | 1 | A15 | T3 | AT2 | — |

| T18 | NT | 1 | C0 | S1 | CS0 | — |

| T19 | 104b | 1 | C0 | S2 | CS1 | — |

| T20 | U302 | 1 | A0 | R7 | AR14 | XIII |

| T21 | 104b | 1 | C2 | S4 | CS3 | — |

| T22 | NT | 1 | A0 | R4 | AR14 | XV |

| T23 | NT | 1 | A0 | R7 | AR14 | XVI |

| T24 | 104b | 1 | C1 | S3 | CS13 | — |

| NAe, R25 | LT2 | A18 | W0 | AW0 | ||

M, S. enterica serovar 4,5,12:i:−; m, S. enterica serovar 4,5,12:−:−, T, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium; R, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2, used as a reference strain.

1, R-ACSSuT; 2, R-ACSSuT-SxTG; 3, R-ASSuT (chloramphencol susceptibility).

NT, Not typed with the available phage library.

—, plasmids not detectable.

NA, not applicable.

PFGE and plasmid profiling.

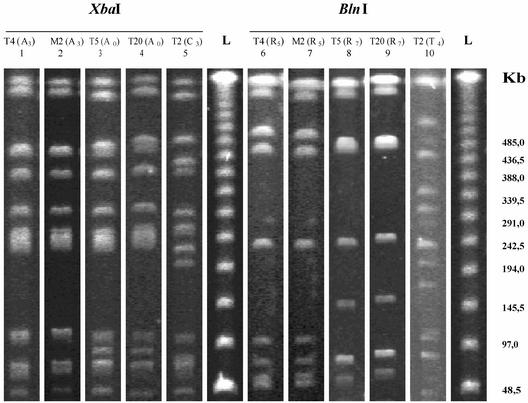

XbaI digestion yielded about nine restriction fragments for most isolates under the conditions used in this study. Three main restriction patterns, patterns A, B, and C, were recognized. Pattern A grouped 17 subtypes of isolates as closely related (subtypes A1 to A9, >80% similarity) or possibly related (subtypes A10 to A17, >65% and <80% similarity) to subtype A0. Profile A0 isolates (n = 7) were only found among serovar Typhimurium isolates from 1998 to 2000, while isolates with profiles that were closely related to subtype A0 (subtypes A1 to A9, n = 19) were observed among the monophasic isolates, not including isolates T3 and T4 (Fig. 1). Patterns B and C grouped two and three subtypes, respectively, and were detected only among serovar Typhimurium or serovar 4,5,12:−:− isolates. With BlnI digestion, we obtained about six restriction fragments for all but four isolates. In these four cases the number of fragments was 10 or more. There were four restriction patterns: types R, S, T, and V, with eight, three, four, and one subtypes, respectively. A different profile, profile W, was assigned to the reference strain. R subtypes R0 to R6 were found among monophasic isolates, and only three serovar Typhimurium phage type DT U302 isolates (isolates T3, T4, and T8) were subtypes R0 to R6, while profiles R7 and R8 were exclusively observed among serovar Typhimurium isolates. The S, T, and V profiles were observed only among serovar Typhimurium or 4,5,12:−:− isolates. Subtypes R1 to R5 were closely related to subtype R0 (similarity, >72%), and subtypes R6 to R9 were possibly related to subtype R0 (similarity, >44% and <60%).

FIG. 1.

PFGE patterns of chromosomal DNA restriction fragments generated with the enzymes XbaI and BlnI for S. enterica serovar Typhimurium isolates (isolates T4, T5, T20, and T2) and a serovar 4,5,12:i:− isolate (isolate M2). Lanes: 1 and 6, serovar Typhimurium DT U302, plasmid profile I, isolated in 1998; 2 and 7, serovar 4,5,12:i:− DT U302, plasmid profile I, isolated in 1999; 3 and 8, serovar Typhimurium DT104, no plasmid, isolated in 1998; 4 and 9, serovar Typhimurium DT U302, plasmid profile XIII, isolated in 2000; 5 and 10, serovar Typhimurium DT 104b, no plasmid, isolated in 1998; L, bacteriophage lambda ladder PFG marker (New England Biolabs).

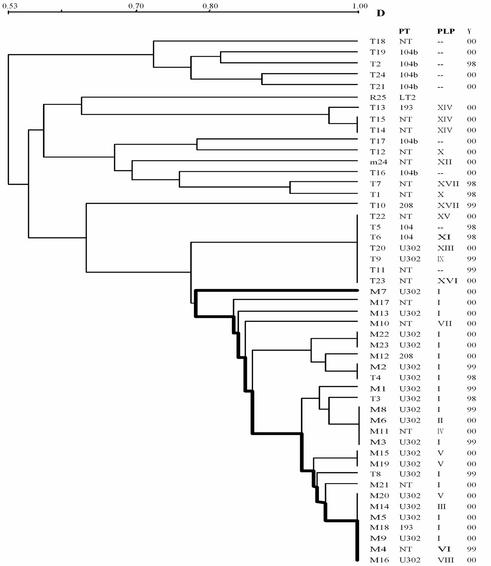

When the results of both enzyme restriction analyses were combined, 29 different profiles were determined, with most profiles (22 profiles) containing only a single strain (Fig. 2). In contrast, seven profiles grouped the remaining 26 strains (e.g., an identical XB profile [profile AR0] was obtained when profiles A10 and R0, A5 and R1, or A5 and R0 were combined). Seven main patterns were observed, with pattern AR (n = 33) being found the most frequently. Profile AR0 (n = 7) was present only among monophasic isolates. Subtypes AR1 to AR12 were closely related to subtype AR0 (similarity, >85%), and subtypes AR13 and AR14 were possibly related to subtype AR0 (similarity, >76% and ≤85%). Patterns AT, AV, BT, BV, CS, and CT grouped a total of 15 strains into 14 different profiles and were observed only among serovar Typhimurium or serovar 4,5,12:−:− isolates. Among the 33 isolates with pattern AR were all 23 isolates with a monophasic serovar and 10 serovar Typhimurium isolates. Of these 10 serovar Typhimurium isolates, 3 (isolates T3, T4, and T8) belonged to the same monophasic cluster, and 7 shared a common XB profile, profile AR14, that was found only among serovar Typhimurium isolates.

FIG. 2.

Average linkage (UPGMA) dendrogram showing results of combined PFGE pattern cluster analysis (combined XB profiles) generated by S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (Tn), S. enterica serovar 4,5,12:i:− (Mn), S. enterica serovar 4,5,12:−:− (m24), and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 (R25). D, similarity coefficient; PT, phage type; PLP, plasmid profile; Y, year of isolation.

Isolates with the combined type BV profiles corresponded to the three multiresistant but chloramphenicol-susceptible serovar Typhimurium isolates included in the study.

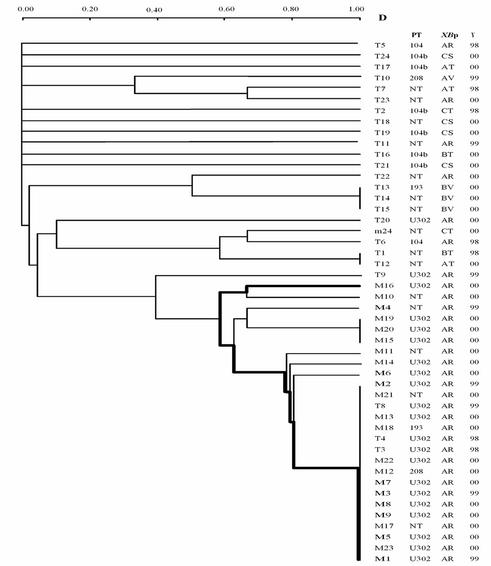

Plasmid profiling yielded 19 patterns, with pattern I being the most common (n = 17). Thirteen type I isolates belonged to phage type U302: 10 serovar 4,5,12:i:− isolates and 3 serovar Typhimurium isolates (isolates T3, T4, T8). All isolates with plasmid profile I also corresponded to PFGE AnRn combinations (Fig. 3). Nine serovar Typhimurium isolates had no detectable plasmids, but no relationship could be established between this fact and any other data collected in the study.

FIG. 3.

Average linkage (UPGMA) dendrogram showing results of plasmid profile cluster analysis generated by S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (Tn), S. enterica serovar 4,5,12:i:− (Mn), and S. enterica serovar 4,5,12:−:− (m24). D, similarity coefficient; PT, phage type; XBp, combined PFGE profiles (XbaI plus BlnI); Y, year of isolation.

DISCUSSION

During the last 15 years, S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium has been ranking second place among the human and nonhuman Salmonella isolates most frequently isolated in Spain (6, 20). Most of these serovar Typhimurium isolates have a common R-ACSSuT pattern and predominantly belong to phage types DT104, DT104b, and DT U302. In 1997, a new serovar with the antigenic formula 4,5,12:i:− emerged and since then has been increasing in frequency. Isolates with this serovar have been associated with swine and pork products (5, 21, 22) and in many cases are classified in the DT U302 phage type (5, 6, 7, 8, 20). In our study, 70% of the 4,5,12:i:− isolates were phage type DT U302, a value higher than that reported previously (21, 22, 23). However, direct comparison with data from other reports may be biased because of the different sampling criteria used.

It has been suggested that there is a close relationship between serovars Typhimurium and 4,5,12:i:−. Thus, serovar 4,5,12:i:− isolates belonging to the DT U302 phage type and having resistance pattern R-ACSSuT-GSxT are thought to be a variant of serovar Typhimurium and lack the second-phase flagellar antigen encoded by fljB (6). However, no information that links other phage types or strains with a different resistance pattern to serovar Typhimurium is available.

When PFGE results were evaluated by using the combined XB profiles, a total of 33 isolates of 48 tested had the AR pattern. Of the 33 isolates with an ARn profile, 23 were monophasic strains sharing more than 85% similarity; isolate M7, however, had 76% similarity. Our results demonstrate that there is a high percentage of similarity among the AR subtypes, while a very degree of high variability is observed among the six patterns that group the remaining 15 isolates. Taking into account the fact that the possible number of profiles increases when two enzymes are combined, our results strongly indicate that the monophasic isolates are part of a clonal lineage or at least have a close common ancestor.

Regarding the method used in this study, the profiles obtained with enzymes XbaI and BlnI alone resolved three and four groups, respectively, with numerous variants. It seems that analysis with the XB combination had a higher discriminatory power than analysis with a single enzyme. As our results demonstrate, if appropriate enzymes are combined, thus yielding an adequate number of restriction fragments, the analysis method of Tenover et al. (19) can also be used to type strains recovered over relatively extended periods of time.

The monophasic cluster included three serovar Typhimurium DT U302 strains: strains T3 and T4, isolated in 1998, and strain T8, isolated in 1999. These strains had an R-ACSSuT-GSxT pattern, which was predominant among the 4,5,12:i:− isolates that we studied. In addition, they shared the same plasmid profile observed for the monophasic strains but not any of the other serovar Typhimurium isolates. This fact supports the theory that DT U302 isolates are closely related, regardless of whether they are serovar Typhimurium or monophasic.

Furthermore, in a cluster of seven serovar Typhimurium isolates with approximately 78% similarity to the monophasic strains, two isolates (isolates T5 and T6) were phage type DT104 and were isolated in 1998. When only those isolates sharing more than 78% similarity to 4,5,12:i:− strains are considered putative ancestral candidates and when the year of isolation is taken into account, it can be seen that in 1998 (the first year in which isolates were studied) the criterion of more than 78% similarity is fulfilled by only two serovar Typhimurium DT104 isolates and two serovar Typhimurium DT U302 isolates.

According to the XB profile results and, more specifically, according to the AR profile assigned to serovar Typhimurium, we observed the same AR14 subtype in all but three isolates (isolates T3, T4, and T8). This subtype was not identified among our monophasic isolates. The AR14 subtype was periodically encountered during the 3 years of this study and both serovar Typhimurium DT104 isolates recovered in 1998 had the AR14 subtype.

As a consequence and by taking into account the close relationship that exists between phage types DT104 and DT U302 (16), one logical hypothesis that can be inferred is that monophasic strains, regardless of their phage type or antibiotic resistance pattern, originate from serovar Typhimurium DT U302 strains, such as the T3 and T4 isolates that we studied. If this could be demonstrated with 4,5,12:i:− strains of other geographical origins, S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar 4,5,12:i:− should no longer be classified as such but should be classified as a monophasic S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium DT U302 variant.

Acknowledgments

This work has been funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnologia of Spain (project AGF99-1234).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, E. S., L. R. Ward, M. J. Saxe, and J. D. de Sa. 1977. Bacteriophage-typing designations of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Hyg. 78:297-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baggesen, D. L., D. Sandvang, and F. M. Aarestrup. 2000. Characterization of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104 isolated from Denmark and comparison with isolates from Europe and the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1581-1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callow, B. R. 1959. A new phage-typing scheme for Salmonella typhimurium. J. Hyg. Camb. 57:346-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carattoli, A., F. Tosini, and P. Visca. 1998. Multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 339:921-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Echeita, M. A., A. Aladueña, S. Cruchaga, and M. A. Usera. 1999. Emergence and spread of an atypical Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype 4:5,12:i:− strain in Spain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Echeita, M. A., S. Herrera, and M. A. Usera. 2001. Atypical, flj-negative Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica strain of serovar 4:5,12:i:− appears to be a monophasic variant of serovar Typhimurium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2981-2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garaizar, J., S. Porwollik, A. Echeita, A. Rementeria, S. Herrera, R. M. Wong, J. Frye, M. A. Usera, and M. McClelland. 2002. DNA microarray-based typing of an atypical monophasic Salmonella enterica serovar. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2074-2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerra, B., I. Laconcha, S. M. Soto, M. A. González-Hevia, and M. C. Mendoza. 2000. Molecular characterisation of emergent multiresistant Salmonella enterica serotype [4,5,12:i:−] organisms causing human salmonellosis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 190:341-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerra, B., S. M. Soto, J. M. Argüelles, and M. C. Mendoza. 2001. Multidrug resistance is mediated by large plasmids carrying a class 1 integron in the emergent Salmonella enterica serotype [4,5,12:i:−]. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1305-1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kariuki, S., J. Cheesbrough, A. K. Mavridis, and C. A. Hart. 1999. Typing of Salmonella enterica serotype Paratyphi C isolates from various countries by plasmid profiles and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2058-2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kariuki, S., J. O. Oundo, J. Muyodi, B. Lowe, E. J. Threlfall, and C. A. Hart. 2000. Genotypes of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium from two regions of Kenya. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 29:9-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu, S. L., and K. E. Sanderson. 1991. A physical map of the Salmonella typhimurium LT2 genome made by using XbaI analysis. J. Bacteriol. 174:1662-1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mateu, E. M., M. Martin, L. Darwich, W. Mejía, N. Frías, and F. J. Garcia Peña. 2002. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Salmonella strains isolated from swine in Catalonia, Spain. Vet. Rec. 150:147-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Popoff, M. Y., and L. Le Minor. 1997. Antigenic formulas of the Salmonella serovars, 7th revision. WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference Research on Salmonella. Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

- 15.Powell, N. G., E. J. Threlfall, H. Chart, and B. Rowe. 1994. Subdivision of Salmonella enteritidis PT 4 by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: potential for epidemiological surveillance. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 119:193-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pritchett, L. C., M. E. Konkel, J. M. Gay, and T. E. Besser. 2000. Identification of DT104 and U302 phage types among Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3484-3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridley, A. M., E. J. Threlfall, and B. Rowe. 1998. Genotypic characterization of Salmonella enteritidis phage types by plasmid analysis, ribotyping, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2314-2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith, C. L., S. R. Klco, and C. R. Cantor. 1988. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and the technology of large DNA molecules, p. 41-72. In K. Davis (ed.), Genome analysis: a practical approach, IRL Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 19.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Usera, M. A., A. Aladueña, R. Diez, M. de la Fuente, F. Gutierrez, R. Cerdán, and A. Echeita. 2000. Análisis de las cepas de Salmonella spp aisladas de muestras clínicas de origen humano en España en el año 1999 (I). Bol. Epidemiol. Semanal. 8:45-48. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Usera, M. A., A. Aladueña, R. Diez, M. de la Fuente, F. Gutierrez, R. Cerdán, and A. Echeita. 2000. Análisis de las cepas de Salmonella spp aisladas de muestras clínicas de origen no humano en España en el año 1999. Bol. Epidemiol. Semanal. 8:133-144. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Usera, M. A., A. Aladueña, R. Diez, M. De la Fuente, F. Gutierrez, R. Cerdán, and A. Echeita. 2001. Análisis de las cepas de Salmonella spp aisladas de muestras clínicas de origen no humano en España en el año 2000. Bol. Epidemiol. Semanal. 9:281-288. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Usera, M. A., A. Aladueña, R. Diez, M. de la Fuente, F. Gutierrez, R. Cerdán, M. Arroyo, R. González, and A. Echeita. 2001. Análisis de las cepas de Salmonella spp aisladas de muestras clínicas de origen humano en España en el año 2000 (I). Bol. Epidemiol. Semanal. 9:221-224. [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Belkum, A., M. Struelens, A. de Visser, H. Verbrugh, and M. Tibayrenc. 2001. Role of genomic typing in taxonomy, evolutionary genetics, and microbial epidemiology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:547-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong, K. K., and M. McClelland. 1992. A BlnI restriction map of the Salmonella typhimurium LT2 genome. J. Bacteriol. 174:1656-1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]