Abstract

A 39-year-old woman with tubarian sterility fell ill with acute pelvic inflammatory disease 2 months after transvaginal oocyte recovery. Laparotomy revealed a large tuboovarian abscess, from which Atopobium vaginae, an anaerobic gram-positive coccoid bacterium of hitherto unknown clinical significance, was isolated. The microbial etiology and the risk of pelvic infections following transvaginal punctures are discussed.

CASE REPORT

In November 2000, a 39-year-old married woman was admitted to our clinic with a 3-day history of severe pain in the lower abdomen. In 1984 the patient had an infection of the adnexa uteri which was treated with antibiotics. In 1987 the right ovary was removed by laparotomy after diagnosis of an endometriotic cyst. In 1991, 1995, and 1997 the patient underwent endoscopic surgery for treatment of abdominal pain due to endometriosis. Considering her 4-year history of unsuccessful attempts to become pregnant, the patient was assumed to suffer from tubarian sterility and was subsequently transferred to our in vitro fertilization program. Between 1992 and 1999, ultrasound-guided transvaginal follicle punctures for oocyte recovery were performed on five different occasions, but embryo transfer was achieved only once and did not lead to pregnancy. It was known that the patient had an asymptomatic endometriotic cyst in the left ovary. At the end of August 2000, two oocytes were recovered (again via transvaginal follicle puncture after disinfection of the vagina with Octenisept [Schülke & Mayr GmbH, Norderstedt, Germany]), fertilized, and transcervically transferred, but again the patient did not get pregnant.

On examination following admittance, the patient showed a localized rigidity in the lower abdomen. There was no fever, but a strong increase in the concentration of C-reactive protein in serum (147 mg/liter), leukocytosis (15,800 leukocytes/μl), and a reduced hemoglobin concentration (10.3 mg/dl) were found. Ultrasound examination revealed a mass in the lower left abdomen. Laparotomy was performed and revealed a left-sided tuboovarian abscess, multiple adhesions between various parts of the colon (sigmoid colon and cecum) and the adnexa uteri, a considerably distended salpinx on the right side, and a highly inflamed appendix. Hysterectomy, bilateral salpingectomy, left-sided ovarectomy, appendectomy, and adhesiolysis were performed, and a swab of the tuboovarian abscess (but not of the appendix or peritoneum) was taken. Following surgery, the patient was treated with cefoxitin (2 g given intravenously three times a day) and metronidazole (0.5 g intravenously twice a day) for 5 days. After 10 days, she was doing well and was discharged.

Histopathological examination confirmed the tuboovarian abscess with numerous neutrophils in the abscess cavity, destroyed villi of the fallopian tube with mucosal ulcerations, and inflamed as well as fibrotic ovarian tissue. It also revealed periappendicitis and peritonitis with membranous exudates and numerous neutrophils in the serosa as well as a beginning purulent appendicitis, which strongly suggests that the infection spread from the tuboovarian abscess to the peritoneum and appendix.

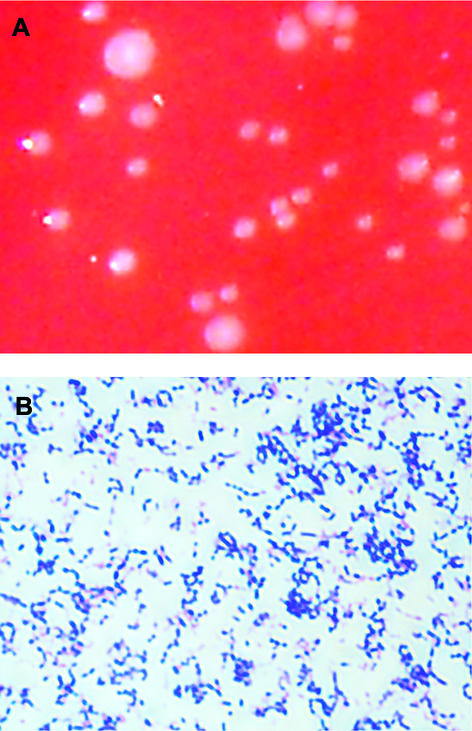

The bacterial swab of the abscess, which was submitted to the microbiology department in a semisolid transportation medium (MAST Diagnostika, Reinfeld, Germany) suitable for both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, yielded the growth of tiny greyish white colonies (Fig. 1A) in the first and second streaks on tryptone soya agar (supplemented with 5% sheep blood, hemin, and vitamin K; Oxoid) within 2 days of culture at 37°C under an anaerobic atmosphere (cultures were held for a total of 6 days). Microscopically, the colonies consisted of small, gram-positive, elliptical cocci that occurred singly, formed pairs, or were grouped as short chains (Fig. 1B). The bacteria were identified as Atopobium vaginae by PCR amplification and sequencing of 1,437 bp of the 16S rRNA gene as described previously (8).

FIG. 1.

(A) Greyish white colonies of A. vaginae after 48 h of culture on tryptone soya agar (supplemented with 5% sheep blood, hemin, and vitamin K) under anaerobic conditions. (B) Gram stain showing gram-positive A. vaginae bacteria occurring singly, in pairs, or as short chains.

The sequence of our isolate (GenBank accession no. AF325325) showed a 99.7% identity to the published A. vaginae 16S rRNA gene sequence (GenBank accession no. Y17195; 1,351 bp), differing only at four positions that were not defined in the original A. vaginae sequence (G instead of N). Furthermore, the morphotype, the microscopic appearance, and the biochemical properties of our isolate were identical to those described in the original report on A. vaginae, except for a positive mannose fermentation (9) (the reaction code in the API ID32A system [BioMérieux] was 2002 0335 05, which gives a misidentification as Gemella morbillorum). However, unlike the facultatively anaerobic isolate described by Rodriguez Jovita et al. (9), our strain of A. vaginae appeared to be a strict anaerobe, because it did not grow in air plus 5% CO2 on blood or chocolate agar. After growth on Columbia blood agar (at 36°C, under anaerobic conditions), whole-cell fatty acid analysis (7) of the A. vaginae isolate under standard Microbial Identification System (MIS) conditions yielded the following pattern of straight-chain saturated and unsaturated fatty acids: decanoic acid (C10:0), 3.01%; tetradecanoic acid (C14:0), 3.24%; pentadecanoic acid (C15:0), 1.51%; palmitic acid (C16:0), 34.83%; heptadecanoic acid (C17:0), 2.0%; stearic acid (C18:0), 17.45%; palmitoleic acid (C16:1ω7c), 1.47%; oleic acid (C18:1ω9c), 25.34%; linoleic acid (C18:2ω6,9c), 9.19%; arachidonic acid (C20:4ω6,9,12,15c), 1.98%. Retrospective antimicrobial testing of the A. vaginae strain (using the agar dilution test and/or the E test [AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden] [5]) demonstrated susceptibility to ampicillin (MIC, 0.032 mg/liter), penicillin G (MIC, 0.125 mg/liter), cefuroxime (MIC, 0.19 mg/liter), cefoxitin (MIC, 2 mg/liter), and imipenem (MIC, 0.016 mg/liter) but complete resistance to metronidazole.

Vaginal or endocervical infections are known for their tendency to ascend locally and to cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which can manifest as salpingitis, pelvic peritonitis, or tuboovarian abscess. The bacteria most frequently isolated from women with PID include Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis as well as various anaerobic gram-positive cocci and rods (e.g., Actinomyces, Peptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, Peptoniphilus, and Finegoldia spp.). In the case reported here, PID was caused by A. vaginae, an anaerobic, gram-positive, elongated coccus of hitherto unknown clinical significance, which was recently described for the first time in the vaginal flora of a healthy woman (9).

The genus Atopobium was introduced only in 1992, when Collins and Wallbanks proposed to rename the species Lactobacillus minutus, Lactobacillus rimae, and Streptococcus parvulus (2). Atopobium rimae, Atopobium parvulum, and Atopobium minutum have been isolated from human gingival crevices and in various human infections (e.g., dental or pelvic abscesses, abdominal wounds) (6, 9), but otherwise the clinical significance of Atopobium species has not been defined to date. This might be due to the fact that these bacteria are not yet included in commercially available differentiation systems and therefore are likely to be misidentified as Lactobacillus or Streptococcus species based on the morphology of their colonies. The present report is the first description of A. vaginae as the causative agent of an infection in humans.

Ultrasound-guided transvaginal punctures for oocyte retrieval can cause pelvic infections. In the few published studies the risk of infection varied between 0.5 and 4% (1, 3, 11). In our department of obstetrics and gynecology we observed two cases of acute pelvic infections in a series of around 800 transvaginal follicle punctures during the past 4 years (unpublished data). Transvaginal punctures for other gynecological purposes bear a similar risk of infection (12). PID may also result from transcervical embryo transfer, because it can occur without prior transvaginal oocyte aspiration (4). The presence of severe endometriosis or ovarian endometriomata, such as existed in our patient, appears to be an additional risk factor for infection after transvaginal oocyte pick-up (10). The overall low incidence of clinically apparent infections is likely to result from efficient antisepsis of the vagina, which in our institution is performed with Octenisept (a broad-spectrum disinfectant for wounds and mucous membranes that contains 2-phenoxyethanol and octenidine-dihydrochloride, a nonabsorbable bispyridine with two cationic centers).

Except for a case of tuboovarian abscess caused by Escherichia coli (4) and a subclinical infection with C. trachomatis (3), no publications are available on the bacterial etiology of pelvic infections after transvaginal punctures. Considering the worldwide increase of in vitro fertilization programs and the wide acceptance of the transvaginal route for oocyte retrieval, microbiological diagnosis should be attempted in all cases of clinically apparent infections following these procedures in order to better define the spectrum of infectious agents as well as possible new prophylactic actions.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The 16S rDNA sequence of the A. vaginae isolate discussed in this paper has been submitted to GenBank under accession no. AF325325.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bung, P., H. Plath, G. Prietl, and D. Krebs. 1996. Ileus in der Spätschwangerschaft—Folge der Follikelpunktion im Rahmen der in vitro-Fertilisation. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 56:252-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins, M. D., and S. Wallbanks. 1992. Comparative sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA genes of Lactobacillus minutus, Lactobacillus rimae and Streptococcus parvulus: proposal for the creation of a new genus Atopobium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 95:235-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curtis, P., N. Amso, E. Keith, A. Bernard, and R. W. Shaw. 1991. Evaluation of the risk of pelvic infection following transvaginal oocyte recovery. Hum. Reprod. 6:1294-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedler, S., I. Ben-Shachar, Y. Abramov, J. G. Schenker, and A. Lewin. 1996. Ruptured tubo-ovarian abscess complicating transcervical cryopreserved embryo transfer. Fertil. Steril. 65:1065-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hecht, D. W. 2002. Evolution of anaerobe susceptibility testing in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35(Suppl. 1):S28-S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jousimies-Somer, H. 1997. Recently described clinically important anaerobic bacteria: taxonomic aspects and update. Clin. Infect. Dis. 25:S78-S87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller, L. T. 1982. Single derivatization method for routine analysis of bacterial whole-cell fatty acid methyl esters, including hydroxy acids. J. Clin. Microbiol. 16:584-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Relman, D. A., P. W. Lepp, K. N. Sadler, and T. M. Schmidt. 1991. Phylogenetic relationship among the agent of bacillary angiomatosis, Bartonella bacilliformis, and other alpha-proteobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1801-1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez Jovita, M., M. D. Collins, B. Sjöden, and E. Falsen. 1999. Characterization of a novel Atopobium isolate from the human vagina: description of Atopobium vaginae sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:1573-1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Younis, J. S., Y. Ezra, N. Laufer, and G. Ohel. 1997. Late manifestations of pelvic abscess following oocyte retrieval for in vitro fertilization in patients with severe endometriosis and ovarian endometriomata. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 14:343-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuzpe, A. A., S. E. Brown, R. F. Casper, J. Nisker, G. Graves, and L. Shatford. 1989. Transvaginal, ultrasound-guided oocyte retrieval for in vitro fertilization. J. Reprod. Med. 34:937-942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zanetta, G., A. Lissoni, D. Franchi, M. R. Pittelli, G. Cormio, and D. Trio. 1996. Safety of transvaginal fine needle puncture of gynecologic masses: a report after 500 consecutive procedures. J. Ultrasound Med. 15:401-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]