Abstract

CCR5-using (R5) human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is a major viral population that is transmitted by sexual intercourse and that replicates in infected individuals during the asymptomatic stage of HIV-1 infection, suggesting that agents effective against R5 HIV-1 can be expected to prevent viral transmission and delay disease progression. However, R5 HIV-1 is unable to replicate in human T-cell lines, which is an apparent obstacle to efficient and reliable susceptibility tests of compounds for their activities against R5 HIV-1. To establish a simple and rapid assay system for the monitoring of R5 HIV-1 replication and drug susceptibility, we have established a novel reporter T-cell line, MOCHA (which represents MOLT-4 cells stably expressing CCR5 and carrying the HIV-1 long terminal repeat-driven secretory alkaline phosphatase). Cells of this cell line express CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5 on their surfaces and secrete human placental alkaline phosphatase into the culture supernatants during HIV-1 infection. MOCHA cells proved to be highly permissive for the replication of R5 HIV-1 as well as CXCR4-using (X4) HIV-1, and the alkaline phosphatase activity increased in parallel with increasing HIV-1 p24 antigen levels in the culture supernatants. When HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors, protease inhibitors, and entry inhibitors, including the CCR5 antagonist TAK-779 and the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100, were examined for their inhibitory effects on R5 and X4 HIV-1 replication in MOCHA cells, the antiviral activities of these compounds were found to be almost identical to those previously reported in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Thus, MOCHA cells are an extremely useful tool for detection of R5 and X4 HIV-1 replication and drug susceptibility tests.

Highly active antiretroviral therapy has achieved high-level suppression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication in infected individuals. However, a recent study on viral dynamics suggests that eradication of HIV-1 from the body may not be feasible (11). Therefore, it still seems mandatory that effective anti-HIV-1 agents with novel mechanisms of action be found and developed. The viral entry process is one of the more promising targets for inhibition of HIV-1, because the efficacy of the fusion inhibitor T-20 has been proven in clinical trials (14, 26). In addition to T-20, other fusion inhibitors, such as chemokine receptor antagonists, also selectively inhibit HIV-1 replication in vitro (10, 16). HIV-1 that uses CCR5 as a coreceptor (CCR5-using [R5] HIV-1) is a major population that is transmitted by sexual intercourse and that replicates in infected individuals during the asymptomatic stage of HIV-1 infection (5, 37). In fact, the natural ligands for CCR5 cells (proteins that are regulated on activation with normal T-cell expression and secretion [RANTES] and macrophage inflammatory proteins 1α and 1β [MIP-1α and MIP-1β]) and their modifications are known to block R5 HIV-1 infection in vitro (1, 8, 23, 30). Furthermore, individuals with a homozygous deletion of the CCR5 gene (CCR5Δ32) are apparently normal and healthy (9, 17, 27), suggesting that CCR5 antagonists inhibitory to R5 HIV-1 replication are expected to delay disease progression without serious side effects. Indeed, some small-molecule CCR5 antagonists have recently been reported (3, 18, 32). However, there is an obstacle to the search for and development of novel CCR5 antagonists as anti-HIV-1 agents, since human cell lines in general do not support R5 HIV-1 replication due to the lack of CCR5 expression on their surfaces (36).

Some groups, including ours, have reported on CCR5-expressing T-cell lines that support R5 HIV-1 infection and replication (2, 19, 34). However, even such cell lines do not completely die after viral infection because of the weak cytopathogenicity of R5 HIV-1, indicating that complicated and laborious methods are required for quantitative detection of R5 HIV-1 replication. Although the HIV-1 p24 antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is widely used for quantitative detection of HIV-1 replication, this assay is relatively expensive and time-consuming and therefore is not suitable for high-throughput screening of compounds. Cell lines carrying an HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR)-driven reporter gene, such as chloramphenicol acetyltransferase, green fluorescent protein, and secretory alkaline phosphatase (SEAP), have been used for measurement of CXCR4-using (X4) HIV-1 replication (12, 21, 22). Among the reporter gene products, SEAP is a common reporter used for systematic analysis of several promoter and enhancer activities (4). This enzyme is released into culture supernatants; and its activity can be determined by a colorimetric, chemiluminescent, or fluorescent assay without cell fixation or lysate preparation.

In this study, we have established a novel line of T cells that stably express CCR5 on their surfaces and that carry the HIV-1 LTR-driven SEAP reporter gene. Cells of the cell line MOCHA (which represents MOLT-4 cells stably expressing CCR5 [MOLT-4/CCR5 cells] and HIV-1 LTR-driven SEAP) are highly permissive for the replication of both R5 and X4 HIV-1 strains and secrete increased levels of alkaline phosphatase into the culture supernatants. Furthermore, the activities of various anti-HIV-1 agents in MOCHA cells were found to be almost identical to those previously reported in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

MOLT-4 cells (clone 8) were propagated and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 U of penicillin G per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml (culture medium). MOLT-4/CCR5 cells (19) were cultured in the presence of G418 (1 mg/ml). HIV-1Ba-L (R5 type) and HIV-1IIIB (X4 type) were used in this study. HIV-1Ba-L and HIV-1IIIB were propagated in MOLT-4/CCR5 and MT-4 cells, respectively. The virus stocks were assessed for their p24 antigen levels and infectious titers in MOLT-4/CCR5 cells and were stored at −80°C until use.

Compounds.

The CCR5 antagonist TAK-779 (3) and the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 (29) were synthesized by Takeda Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan). T-20 (35) was purchased from the Peptide Research Institute (Osaka, Japan). Stavudine (d4T), lamivudine (3TC), nevirapine (NVP), indinavir (IDV), and nelfinavir (NFV) were also prepared by Takeda Chemical Industries. Except for AMD3100 and T-20, all compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a concentration of 20 mM to exclude the antiviral and cytotoxic effects of the dimethyl sulfoxide in the culture medium. AMD3100 and T-20 were dissolved at concentrations of 20 mM and 2 mg/ml in water and RPMI 1640, respectively.

Construction of reporter gene.

HIV-1 proviral DNA was extracted from HIV-1IIIB-infected cells with a DNA extraction kit (Wako, Osaka, Japan), and a part of the HIV-1 LTR (from positions −138 to +82) was amplified by PCR with Ex-Taq (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). The amplified product was inserted into the BglII-HindIII cloning site of pSEAP2 Basic (CLONTECH, Palo Alto, Calif.), which encodes a human placental SEAP gene. This plasmid (LTR-SEAP) was used for establishment of MOCHA cells. The HIV-1 LTR sequence was confirmed by use of the ABI PRISM 310 sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

Establishment of MOCHA cells.

The procedures used for plasmid transfection and the selection of stable transfectants have been described previously (2). Briefly, LTR-SEAP and pPURO (CLONTECH), which encodes puromycin resistance, were mixed at a ratio of 10:1 and transfected into MOLT-4/CCR5 cells with Lipofectamine2000 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.). Stably transfected cells were selected in culture medium containing 500 μg of G418 per ml and 0.1 μg of puromycin per ml. The cells were cultured together with mitomycin C-treated MOLT-4 cells (feeder cells) and were cloned by limiting dilution. The SEAP activities of the culture supernatants of the selected clones were determined. To confirm the Tat-dependent transcriptional activation of the SEAP gene, an HIV-1 Tat-expressing vector was transiently transfected into the clones. The clones were also examined for their expression of CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 on their surfaces with a FACScan instrument (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.).

Flow cytometric analysis.

MOLT-4, MOLT-4/CCR5, and MOCHA cells were analyzed for their surface expression of CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 (2). The cells (5 × 105) were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-CCR5 monoclonal antibody (MAb) 2D7, phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CXCR4 MAb 12G5, FITC-labeled anti-CD4 MAb RPA-T4, or isotype-matched control MAbs for 30 min at 4°C. The cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, fixed with 2% formaldehyde, and analyzed with the FACScan instrument (Becton Dickinson). All MAbs used in this study were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.).

HIV-1 replication assay.

MOLT-4/CCR5 and MOCHA cells (105) were infected with HIV-1Ba-L or HIV-1IIIB at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01. After incubation for 2 h at 37°C, the cells were washed thoroughly with culture medium to remove unabsorbed virus particles and were further incubated in a 48-well culture plate. On day 4 after virus infection, the cells were subcultured at a ratio of 1:5 and incubated for an additional 4 days. At the end of the incubation period, the culture supernatants were collected and examined for their p24 levels.

Reporter activity assay.

MOCHA cells (2 × 104) were infected with various amounts (3.2 to 50,000 50% cell culture infective doses [CCID50s]) of HIV-1Ba-L or HIV-1IIIB per well. On day 5 after virus infection, the cells were subcultured at a ratio of 1:5 and further incubated. On day 10, the SEAP activities and the p24 antigen levels in the culture supernatants were determined by chemiluminescence assay and ELISA, respectively. The SEAP activities were measured with the GreatEscape SEAP detection kit (CLONTECH), according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The chemiluminescence intensity was measured with an LB96P luminometer (Berthold, Wildbad, Germany) and expressed as relative light units (RLUs).

Assays of anti-HIV-1 activities.

MOCHA cells (2 × 104) were infected with 1,000 CCID50s of HIV-1Ba-L or HIV-1IIIB in the presence of various concentrations of test compounds and incubated in a microtiter plate. On day 5 after virus infection, the cells were subcultured at a ratio of 1:5 and further incubated. On day 10, the culture supernatants were collected and examined for their SEAP activities. The 50% effective concentration (EC50) of each compound was calculated by least-squares linear regression analysis over the ascending linear portion of the dose-response curve. The cytotoxicities of the test compounds were also evaluated in parallel with their anti-HIV-1 activities on day 10. Cytotoxicity was based on the proliferation and viability of mock-infected MOCHA cells, as determined by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) method (25).

RESULTS

Establishment of MOCHA cells.

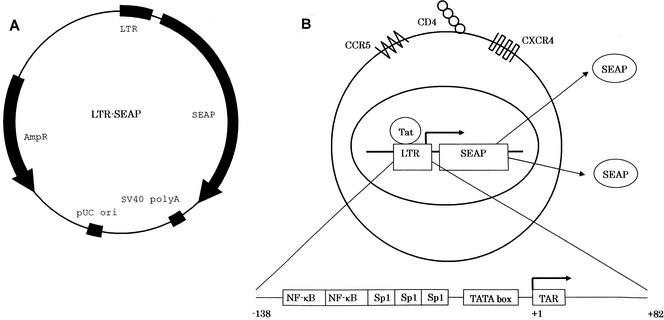

To establish an R5 HIV-1-permissive T-cell line carrying an HIV-1 LTR-driven reporter gene, MOLT-4/CCR5 cells were used as the starting material. MOLT-4/CCR5 cells were previously established for the evaluation of CCR5 antagonists of R5 HIV-1 replication (2). Furthermore, SEAP was chosen as a reporter. The region of the HIV-1 LTR from positions −138 to +82 was amplified and inserted into the upstream region of the reporter gene (LTR-SEAP). Such truncation of the HIV-1 LTR decreased the basal level of expression of the reporter gene in the absence of Tat (15). To obtain clones stably carrying LTR-SEAP, cells were selected in the presence of puromycin after cotransfection of LTR-SEAP and pPURO (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic presentation of the LTR-SEAP plasmid and MOCHA cells. (A) The LTR (positions −138 to +82 in reference to the transcriptional start site at position +1) from HIV-1IIIB was cloned into the cloning site of the pSEAP2 basic reporter plasmid, as described in Materials and Methods. (B) MOCHA cells expressing CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5 molecules are permissive for R5 HIV-1 as well as X4 HIV-1. After HIV-1 infection, the viral activator Tat induces HIV-1 LTR-regulated SEAP reporter expression, which is detectable in the culture supernatants. The LTR contains two NF-κB and three Sp1 binding sites as well as the TATA box and the transactivation responsive element (TAR). SV40, simian virus 40.

Since significant down-regulation of CD4 expression on the surfaces of the puromycin-resistant clones was observed, additional cloning of single cells was performed twice to obtain a clone with a sufficient level of CD4 expression. The MOLT-4/CCR5 clone MOCHA cells expressed identical levels of CCR5 and CXCR4 on their surfaces compared with the levels of expression on the surfaces of MOLT-4 and MOLT-4/CCR5 cells. The level of CD4 expression by MOCHA cells was still slightly lower than that by the parental cells (Fig. 2), yet the level appeared to be sufficient for HIV-1 infection. The expression of these molecules was stable during at least 3 months of culture.

FIG. 2.

Surface expression of CCR5, CXCR4, and CD4 in MOLT-4, MOLT-4/CCR5, and MOCHA cells. The cells were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CCR5, and anti-CXCR4 MAbs (solid line) or isotype-matched control MAbs (dotted line) and analyzed with a fluorescence-activated cell sorter, as described in Materials and Methods.

HIV-1 replication in MOCHA cells.

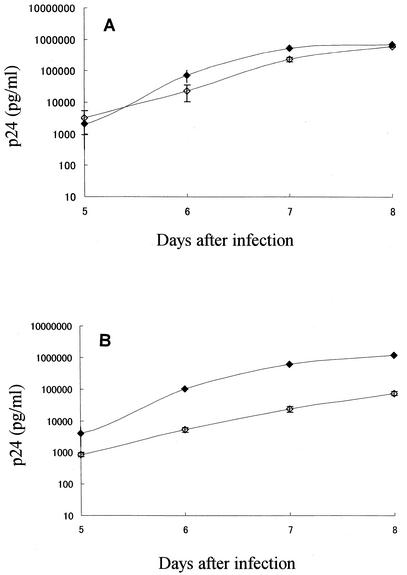

To examine whether MOCHA cells supported HIV-1 replication, MOCHA and MOLT-4/CCR5 cells were infected with HIV-1IIIB and HIV-1Ba-L. As shown in Fig. 3, both MOCHA and MOLT-4/CCR5 cells were found to be permissive for the replication of HIV-1IIIB and HIV-1Ba-L. The levels of p24 antigen were 2.1 ± 1.8 and 3.2 ± 2.3 ng/ml for MOLT-4/CCR5 and MOCHA cells, respectively, on day 5 after infection with HIV-1IIIB (Fig. 3A). Increased p24 antigen levels were observed on day 8 (705 ± 61 and 617 ± 22 ng/ml for MOLT-4/CCR5 and MOCHA cells, respectively). These results indicate that MOCHA and MOLT-4/CCR5 cells are equally permissive for the replication of HIV-1IIIB, a representative strain of X4 HIV-1. In the case of HIV-1Ba-L infection, p24 antigen levels were 4.0 ± 2.5 and 0.84 ± 2.5 ng/ml for MOLT-4/CCR5 and MOCHA cells, respectively, on day 5 (Fig. 3B). Similar to HIV-1IIIB infection, increased p24 antigen levels were identified on day 8. The antigen levels were 1,206 ± 243 ng/ml for MOLT-4/CCR5 cells and 74.5 ± 10.4 ng/ml for MOCHA cells, suggesting that MOCHA cells are slightly less permissive than MOLT-4/CCR5 cells for the replication of HIV-1Ba-L, a representative strain of R5 HIV-1.

FIG. 3.

HIV-1 replication in MOLT-4/CCR5 and MOCHA cells. MOLT-4/CCR5 (closed diamonds) and MOCHA (open diamonds) cells were infected with HIV-1IIIB (A) or HIV-1Ba-L (B). The cells were cultured for 8 days after virus infection, and the p24 antigen levels in the culture supernatants were determined on days 5 to 8. The data represent the means ± standard deviations for triplicate wells.

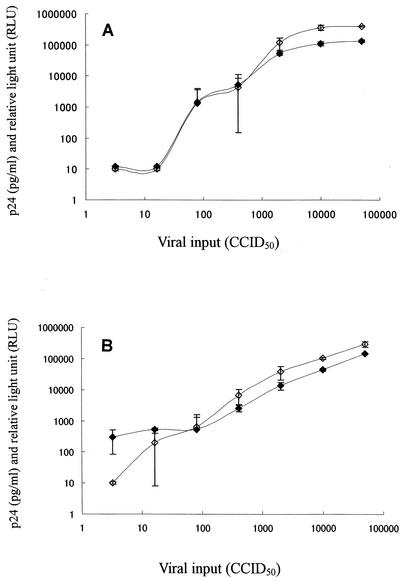

Comparison between reporter activity and p24 antigen production.

To determine whether the reporter activity is correlated with HIV-1 replication in MOCHA cells, the cells were infected with various amounts of HIV-1IIIB or HIV-1Ba-L, and the culture supernatants were examined for SEAP activities and p24 antigen levels. As shown in Fig. 4, both SEAP activities and p24 antigen levels increased on day 10 after infection when a higher infectious dose was used. More than 80 CCID50s of HIV-1IIIB was required for detection of SEAP activity and p24 antigen in the culture supernatants. The values for both of the parameters reached a plateau when the cells were infected with more than 10,000 CCID50s (Fig. 4A). Sixteen CCID50s of HIV-1Ba-L was required for detection of p24 antigen, whereas only 3.2 CCID50s was sufficient for detection of SEAP activity (Fig. 4B). These results clearly demonstrate a close correlation between reporter activity and p24 antigen production in HIV-1-infected MOCHA cells, irrespective of the coreceptor usage of HIV-1 (X4 or R5).

FIG. 4.

Comparison of SEAP activities and p24 antigen levels for HIV-1-infected MOCHA cells. The cells were infected with various amounts of HIV-1IIIB (A) or HIV-1Ba-L (B). SEAP activities (closed diamonds) and p24 antigen levels (open diamonds) in the culture supernatants were determined on day 10 after virus infection. Detection limits were 10 pg/ml for p24 antigen and 10 RLUs for SEAP activity. The data represent the means ± standard deviations for triplicate wells.

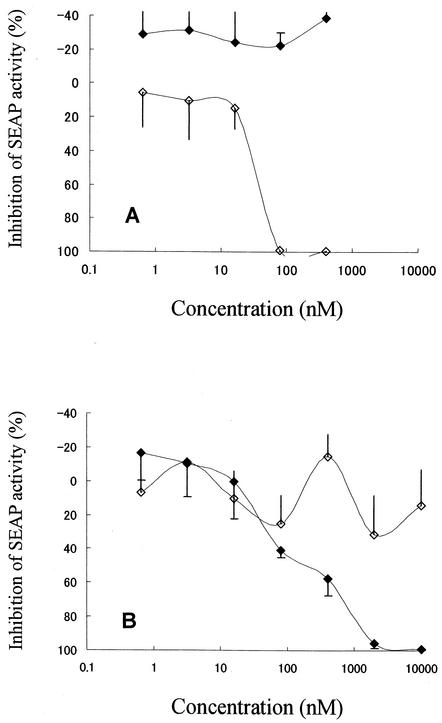

Activities of compounds against HIV-1 in MOCHA cells.

It would be of particular interest to know whether MOCHA cells could be applied to the evaluation of HIV-1 entry inhibitors. The cells were infected with 1,000 CCID50s of either HIV-1IIIB or HIV-1Ba-L in the presence or absence of TAK-779 or AMD3100 and cultured for 10 days. In the absence of compounds, the levels of SEAP activity in the culture supernatants of the infected and mock-infected cells were approximately 70,000 and 7,000 light units, respectively. Furthermore, the SEAP activity in the culture medium without MOCHA cells was 2,000 light units, indicating some basal HIV-1 LTR activity in the cells. AMD3100 clearly inhibited the SEAP activity induced by HIV-1IIIB replication in MOCHA cells (Fig. 5A), and its EC50 was 39 ± 16 nM (Table 1). In contrast, TAK-779 did not show any inhibition of HIV-1IIIB replication, as reported previously (3). On the other hand, TAK-779 strongly inhibited the replication of HIV-1Ba-L (Fig. 5B), with an EC50 of 26 ± 4 nM (Table 1), while AMD3100 was not active against HIV-1Ba-L even at a concentration of 10 μM (Fig. 5B). AMD3100 and TAK-779 at concentrations up to 5 μM did not cause any cytotoxic effects on mock-infected MOCHA cells. Furthermore, these compounds did not affect the basal HIV-1 LTR activity (data not shown). T-20 was found to be equally inhibitory to R5 and X4 HIV-1 (EC50s, 170 ± 62 ng/ml for HIV-1Ba-L and 210 ± 44 ng/ml for HIV-1IIIB) (Table 1).

FIG. 5.

Inhibitory effects of coreceptor antagonists on HIV-1 replication in MOCHA cells. The cells were infected with HIV-1IIIB (A) or HIV-1Ba-L (B) in the presence of various concentrations of TAK-779 (closed diamonds) and AMD3100 (open diamonds). The SEAP activities in the culture supernatants were determined on day 10 after virus infection. The data represent the means ± standard deviations for triplicate wells.

TABLE 1.

Activities of various compounds against HIV-1 in MOCHA cellsa

| Compound | Target | EC50b

|

CC50 (nM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1Ba-L | HIV-1mB | |||

| d4T | RT | 21 ± 3 | 46 ± 32 | >5,000 |

| 3TC | RT | 290 ± 160 | 310 ± 170 | >5,000 |

| NVP | RT | 25 ± 6 | 33 ± 15 | >5,000 |

| TAK-779 | CCR5 | 26 ± 4 | >5,000 | >5,000 |

| AMD3100 | CXCR4 | >5,000 | 39 ± 16 | >5,000 |

| IDV | Pr | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 1.3 | >5,000 |

| NFV | Pr | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | >5,000 |

| T-20 | gp41 | 170 ± 62 | 210 ± 44 | ND |

All data represent means ± standard deviations for three independent experiments. Abbreviations: EC50, concentration required to reduce SEAP activity in the culture supernatants by 50% of that for the control (in the absence of compounds); CC50, concentration required to reduce the viable number of mock-infected MOCHA cells by the MTT assay; RT, reverse transcriptase; Pr, protease; ND, not determined.

The units are in manomolar for all compounds except T-20, for which the units are in manograms per milliliter.

In addition to the entry inhibitors, the activities of several compounds approved for clinical use were evaluated against HIV-1 in MOCHA cells. As shown in Table 1, all of the compounds, such as d4T, 3TC, NVP, IDV, and NFV, proved to be equally inhibitory to the replication of HIV-1Ba-L and HIV-1IIIB in MOCHA cells. For instance, the EC50s of the nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor NVP were 25 ± 6 nM for HIV-1Ba-L and 33 ± 15 nM for HIV-1IIIB. Furthermore, the EC50s in Table 1 are almost identical to those previously reported for HIV-1 in PBMCs (3, 7, 24, 28, 29, 35). These results suggest that the anti-HIV-1 activities of a wide variety of compounds with different mechanisms of action can be evaluated in the system with MOCHA cells described here.

DISCUSSION

There are certain advantages of cell lines over PBMCs for use in the screening of anti-HIV-1 compounds. The results obtained by assays with PBMCs are often dependent on the level of CCR5 expression of the donor cells and even on the state of activation of the PBMCs from the same donor. In particular, compounds targeting CCR5 are difficult to evaluate in PBMCs, because only a small population of the cells express CCR5 on the cell surface. Furthermore, the level of CCR5 expression differs from one donor to another (36). We have previously reported on the CCR5 expression of the T-cell line MOLT-4/CCR5, which is capable of detecting the anti-HIV-1 activity of the small-molecule CCR5 antagonist TAK-779 (2). This cell line is highly permissive for both laboratory-adapted and primarily isolated R5 HIV-1.

Starting with MOLT-4/CCR5 cells as the parental cell line, we have established a novel reporter cell line that expresses CCR5, CXCR4, and CD4 on the cell surface and that carries the HIV-1-driven SEAP reporter gene. The cell line MOCHA is also permissive for both R5 and X4 HIV-1 without the addition of any chemical reagents, such as polybrene, to facilitate infection. However, viral replication was slightly slower in MOCHA cells than in MOLT-4/CCR5 cells. It is assumed that the Tat protein produced in the infected cells interacts not only with the LTR of replicating virus but also with that of the reporter gene. Nevertheless, the activation of SEAP could be easily detected in the culture supernatants of infected cells, and the level of activity was comparable to the p24 antigen levels (Fig. 3 and 4).

The use of SEAP activity as the end point is superior to that of p24 antigen levels for the following reasons. First, the detection of SEAP activity by chemiluminescence is easier and less time-consuming than p24 antigen detection by ELISA. There is no need to prepare cell lysates for measurement of enzyme activities, since SEAP is released into the culture supernatants. These properties are favorable for the screening of large numbers of compounds from chemical libraries. Second, the procedure used to measure SEAP activity includes heat inactivation (65°C for 30 min) of the alkaline phosphatase derived from fetal bovine serum in the culture supernatants. This treatment effectively abrogates viral infectivity, thereby greatly diminishing the biohazards associated with assays based on HIV-1 replication (13, 20). Third, after virus infection the cells do not need to be washed for determination of SEAP activity. Test compounds can exist together with the cells before and during virus infection, which is of particular importance for entry inhibitors to exert their maximum anti-HIV-1 activities.

It is clear that several steps in the HIV-1 replication cycle are involved in the activation of the reporter gene in MOCHA cells. Viral entry into the host cells, reverse transcription of viral RNA, integration of proviral DNA into the host cell genome, and expression of the Tat protein through transcription and translation are at least required for the production of SEAP. Therefore, inhibitors that interfere with one of these steps could decrease the level of SEAP activity. Furthermore, the anti-HIV-1 activities of protease inhibitors are also detectable in MOCHA cells (Table 1), because multiround replication of HIV-1 occurs during the incubation period under assay conditions with a low multiplicity of infection. Thus, the present assay system should be able to detect compounds with any mechanisms of action against HIV-1. In addition, MOCHA cells can also be used in the cell-to-cell membrane fusion assay recently established with the HeLa cell-based reporter cell line MAGI-CCR5 (6, 33). It was confirmed that MOCHA cells could be used as substitutes for MAGI-CCR5 cells in the membrane fusion assay. Furthermore, MOCHA cells may have great potential for use in the determination of drug resistance in phenotypic assays. Although genotypic methods are widely used and rely on a well-documented repertory of known resistance mutations, phenotypic methods that use MOCHA cells may be able to identify mutations unknown at present, in particular, those related to resistance to CCR5 antagonists.

Finally, another CCR5-expressing reporter T-cell line, CEM.NKR-CCR5-Luc, has recently been reported (31). Like MOCHA cells, CEM.NKR-CCR5-Luc cells also seem to be useful for high-throughput screening of anti-HIV-1 compounds. However, the cells require polybrene for efficient HIV-1 infection. Polybrene may affect the interaction between HIV-1 and the host cell membrane, which should be avoided in the evaluation of entry inhibitors. In conclusion, MOCHA cells are an extremely useful tool for the rapid detection of R5 and X4 HIV-1 replication and drug susceptibilities.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Shiki for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arenzana-Seisdedos, F., J.-L. Virelizier, D. Rousset, I. Clark-Lewis, P. Loetscher, B. Moser, and M. Baggiolini. 1996. HIV blocked by chemokine antagonist. Nature 383:400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba, M., H. Miyake, M. Okamoto, Y. Iizawa, and K. Okonogi. 2000. Establishment of a CCR5-expressing T-lymphoblastoid cell line highly susceptible to R5 HIV type 1. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:935-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baba, M., O. Nishimura, N. Kanzaki, M. Okamoto, H. Sawada, Y. Iizawa, M. Shiraishi, Y. Aramaki, K. Okonogi, Y. Ogawa, K. Meguro, and M. Fujino. 1999. A small-molecule, nonpeptide CCR5 antagonist with highly potent and selective anti-HIV-1 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:5698-5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger, J., J. Hauber, R. Hauber, R. Geiger, and B. R. Cullen. 1988. Secreted placental alkaline phosphatase: a powerful new quantitative indicator of gene expression in eukaryotic cells. Gene 66:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjorndal, A., H. Deng, M. Jansson, J. R. Fiore, C. Colognesi, A. Karlsson, J. Albert, G. Scarlatti, D. R. Littman, and E. M. Fenyo. 1997. Coreceptor usage of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates varies according to biological phenotype. J. Virol. 71:7478-7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chackerian, B., E. M. Long, P. A. Luciw, and J. Overbaugh. 1997. HIV-1 co-receptors participate in post-entry stages of the virus replication cycle and function in SIV infection. J. Virol. 71:3932-3939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu, C. K., R. F. Schinazi, B. H. Arnold, D. L. Cannon, B. Doboszewski, V. B. Bhadti, and Z. P. Gu. 1988. Comparative activity of 2′,3′-saturated and unsaturated pyrimidine and purine nucleosides against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 37:3543-3548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cocchi, F., A. L. DeVico, A. Garzino-Demo, S. K. Arya, R. C. Gallo, and P. Lusso. 1995. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science 270:1811-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dean, M., M. Carrington, C. Winkler, G. A. Huttley, M. W. Smith, R. Allikmets, J. J. Goedert, S. P. Buchbinder, E. Vittinghoff, E. Gomperts, S. Donfield, D. Vlahov, R. Kaslow, A. Saah, C. Rinaldo, R. Detels, Hemophilia Growth and Development Study, Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study, San Francisco City Cohort, Alive Study, and S. J. O'Brien. 1996. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CKR5 structural gene. Science 273:1856-1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Clercq, E., and D. Schols. 2001. Inhibition of HIV infection by CXCR4 and CCR5 chemokine receptor antagonists. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 12(Suppl. 1):19-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finzi, D., J. Blankson, J. D. Siliciano, J. B. Margolick, K. Chadwick, T. Pierson, K. Smith, J. Lisziewicz, F. Lori, C. Flexner, T. C. Quinn, R. E. Chaisson, E. Rosenberg, B. Walker, S. Gange, J. Gallant, and R. F. Siliciano. 1999. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat. Med. 5:512-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gervaix, A., D. West, L. M. Leoni, D. D. Richman, F. Wong-Staal, and J. Corbeil. 1997. A new reporter cell line to monitor HIV infection and drug susceptibility in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:4653-4658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawamura, M., T. Naito, M. Ueno, T. Akagi, K. Hiraishi, I. Takai, M. Makino, T. Serizawa, K. Sugiyama, M. Akashi, and M. Baba. 2002. Induction of mucosal IgA following intravaginal administration of inactivated HIV-1-caputuring nanospheres in mice. J. Med. Virol. 66:291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kilby, J. M., S. Hopkins, T. M. Venetta, B. DiMassimo, G. A. Cloud, J. Y. Lee, L. Alldredge, E. Hunter, D. Lambert, D. Bolognesi, T. Matthews, M. R. Johnson, M. A. Nowak, G. M. Shaw, and M. S. Saag. 1998. Potent suppression of HIV-1 replication in humans by T-20, a peptide inhibitor of gp41-mediated virus entry. Nat. Med. 4:1302-1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimpton, J., and M. Emerman. 1992. Detection of replication-competent and pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus with a sensitive cell line on the basis of activation of an integrated β-galactosidase gene. J. Virol. 66:2232-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaBranche, C. C., G. Galasso, J. P. Moore, D. P. Bolognesi, M. S. Hirsch, and S. M. Hammer. 2001. HIV fusion and its inhibition. Antivir. Res. 50:95-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu, R., W. A. Paxton, S. Choe, D. Ceradini, S. R. Martin, R. Horuk, M. E. MacDonald, H. Stuhlmann, R. A. Koup, and N. R. Landau. 1996. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell 86:367-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maeda, K., K. Yoshimura, S. Shibayama, H. Habashita, H. Tada, K. Sagawa, T. Miyakawa, M. Aoki, D. Fukushima, and H. Mitsuya. 2001. Novel low molecular weight spirodiketopiperazine derivatives potently inhibit R5 HIV-1 infection through their antagonistic effects on CCR5. J. Biol. Chem. 276:35194-35200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maeda, Y., M. Foda, S. Matsushita, and S. Harada. 2000. Involvement of both the V2 and V3 regions of the CCR5-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope in reduced sensitivity to macrophage inflammatory protein 1α. J. Biol. Chem. 74:1787-1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDougal, J. S., L. S. Martin, S. P. Cort, M. Mozen, C. M. Heldebrant, and B. L. Evatt. 1985. Thermal inactivation of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome virus, human T lymphotropic virus-III/lymphadenopathy-associated virus, with special reference to antihemophilic factor. J. Clin. Investig. 76:875-877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Means, R. E., T. Greenough, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1997. Neutralization sensitivity of cell culture-passaged simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 71:7895-7902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merzouki, A., P. Patel, S. Cassol, M. Ennaji, P. Tailor, F. R. Turcotte, M. O'Shaughnessy, and M. Arella. 1995. HIV-1 gp120/160 expressing cells upregulate HIV-1 LTR directed gene expression in a cell line transfected with HIV-1 LTR-reporter gene constructs. Cell. Mol. Biol. 4:445-452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosier, D. E., G. R. Picchio, R. J. Gulizia, R. Sabbe, P. Poignard, L. Picard, R. E. Offord, D. A. Thompson, and J. Wilken. 1999. Highly potent RANTES analogues either prevent CCR5-using human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in vivo or rapidly select for CXCR4-using variants. J. Virol. 73:3544-3550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patick, A. K., H. Mo, M. Markowitz, K. Appelt, B. Wu, L. Musick, V. Kalish, S. Kaldor, S. Reich, D. Ho, and S. Webber. 1996. Antiviral resistance studies of AG1343, an orally bioavailable inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus protease. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:292-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pauwels, R., J. Balzarini, M. Baba, R. Snoeck, D. Schols, P. Herdewijn, J. Desmyter, and E. De Clercq. 1988. Rapid and automated tetrazolium-based colorimetric assay for the detection of anti-HIV compounds. J. Virol. Methods 20:309-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pilcher, C. D., J. J. Eron, Jr., L. Ngo, A. Dusek, P. Sista, J. Gleavy, D. Brooks, T. Venetta, E. DiMassimo, and S. Hopkins. 1999. Prolonged therapy with the fusion inhibitor T-20 in combination with oral antiretroviral agents in an HIV-infected individual. AIDS 13:2171-2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samson, M., F. Libert, B. J. Doranz, J. Rucker, C. Liesnard, C.-M. Farber, S. Saragosti, C. Lapoumeroulie, J. Cognaux, C. Forceille, G. Muyldermans, C. Verhofstede, G. Burtonboy, M. Georges, T. Imai, S. Rana, Y. Yi, R. J. Smyth, R. G. Collman, R. W. Doms, G. Vassart, and M. Parmentier. 1996. Resistance to HIV-1 infection in Caucasian individuals bearing mutant alleles of the CCR-5 chemokine receptor gene. Nature 382:722-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schinazi, R. F., R. M. Lloyd, Jr., M. H. Nguyen, D. L. Cannon, A. McMillan, N. Ilksoy, C. K. Chu, D. C. Liotta, H. Z. Bazmi, and J. W. Mellors. 1993. Characterization of human immunodeficiency viruses resistant to oxathiolane-cytosine nucleosides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:875-881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schols, D., S. Struyf, J. Van Damme, J. A. Este, G. Henson, and E. De Clercq. 1997. Inhibition of T-tropic HIV strains by selective antagonization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J. Exp. Med. 186:1383-1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simmons, G., P. R. Clapham, L. Picard, R. E. Offord, M. M. Rosenkilde, T. W. Schwartz, P. Buser, T. N. C. Wells, and A. E. I. Proudfoot. 1997. Potent inhibition of HIV-1 infectivity in macrophages and lymphocytes by a novel CCR5 antagonist. Science 276:276-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spenlehauer, C., C. A. Gordon, A. Trkola, and J. P. Moore. 2001. A luciferase-reporter gene-expressing T-cell line facilitates neutralization and drug-sensitivity assays that use either R5 or X4 strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Virology 280:292-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strizki, J. M., S. Xu, N. E. Wagner, L. Wojcik, J. Liu, Y. Hou, M. Endres, A. Palani, S. Shapiro, J. W. Clader, W. J. Greenlee, J. R. Tagat, S. McCombie, K. Cox, A. B. Fawzi, C.-C. Chou, C. Pugliese-Sivo, L. Davis, M. E. Moreno, D. D. Ho, A. Trkola, C. A. Stoddart, J. P. Moore, G. R. Reyes, and B. M. Baroudy. 2001. SCH-C (SCH 351125), an orally bioavailable, small molecule antagonist of the chemokine receptor CCR5, is a potent inhibitor of HIV-1 infection in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:12718-12723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takashima, K., H. Miyake, R. A. Furuta, J.-I. Fujisawa, Y. Iizawa, N. Kanzaki, M. Shiraishi, K. Okonogi, and M. Baba. 2001. Inhibitory effects of small-molecule CCR5 antagonists on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope-mediated membrane fusion and viral replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3538-3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trkola, A., J. Matthews, C. Gordon, T. Ketas, and J. P. Moore. 1999. A cell line-based neutralization assay for primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates that use either the CCR5 or the CXCR4 coreceptor. J. Virol. 73:8966-8974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wild, C. T., D. C. Shugars, T. K. Greenwell, C. B. McDanal, and T. J. Matthews. 1994. Peptides corresponding to a predictive α-helical domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 are potent inhibitors of virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:9770-9774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu, L., W. A. Paxton, N. Kassam, N. Ruffing, J. B. Rottman, N. Sullivan, H. Choe, J. Sodroski, W. Newman, R. A. Koup, and C. R. Mackay. 1997. CCR5 levels and expression pattern correlate with infectability by macrophage-tropic HIV-1, in vitro. J. Exp. Med. 185:1681-1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang, Y.-J., T. Dragic, Y. Cao, L. Kostrikis, D. S. Kwon, D. R. Littman, V. N. Kewalramani, and J. P. Moore. 1998. Use of coreceptors other than CCR5 by non-syncytium-inducing adult and pediatric isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is rare in vitro. J. Virol. 72:9337-9344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]