Abstract

The metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) agonist trans-(±)-1-amino-1,3-cyclopentanedicarboxylic acid (trans-ACPD) (10–100 μM) depolarized isolated frog spinal cord motoneurones, a process sensitive to kynurenate (1.0 mM) and tetrodotoxin (TTX) (0.783 μM).

In the presence of NMDA open channel blockers [Mg2+; (+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5,10-imine hydrogen maleate (MK801); 3,5-dimethyl-1-adamantanamine hydrochloride (memantine)] and TTX, trans-ACPD significantly potentiated NMDA-induced motoneurone depolarizations, but not α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-proprionate (AMPA)- or kainate-induced depolarizations.

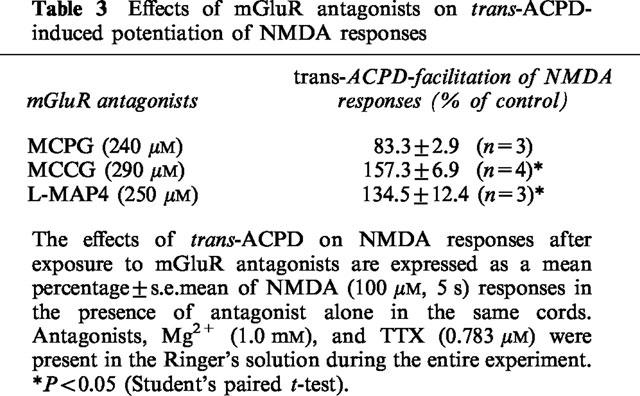

NMDA potentiation was blocked by (RS)-α-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine (MCPG) (240 μM), but not by α-methyl-(2S,3S,4S)-α-(carboxycyclopropyl)-glycine (MCCG) (290 μM) or by α-methyl-(S)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate (L-MAP4) (250 μM), and was mimicked by 3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) (30 μM), but not by L(+)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate (L-AP4) (100 μM). Therefore, trans-ACPD's facilitatory effects appear to involve group I mGluRs.

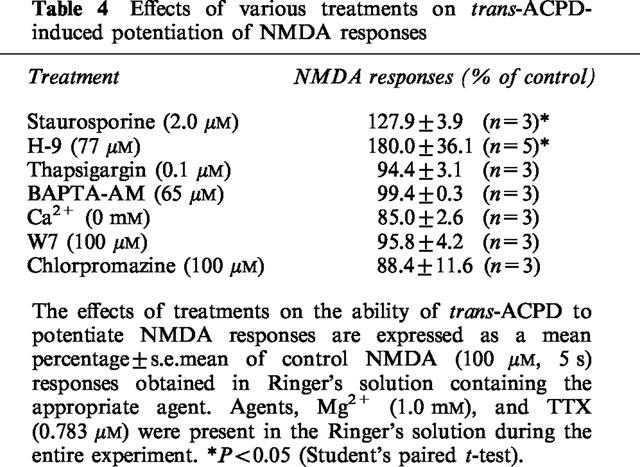

Potentiation was prevented by the G-protein decoupling agent pertussis toxin (3–6 ng ml−1, 36 h preincubation). The protein kinase C inhibitors staurosporine (2.0 μM) and N-(2-aminoethyl)-5-isoquinolinesulphonamide HCl (H9) (77 μM) did not significantly reduce enhanced NMDA responses. Protein kinase C activation with phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate (5.0 μM) had no effect.

Intracellular Ca2+ depletion with thapsigargin (0.1 μM) (which inhibits Ca2+/ATPase), 1,2-bis(O-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetracetic acid acetyl methyl ester (BAPTA-AM) (50 μM) (which buffers elevations of [Ca2+]i), and bathing spinal cords in nominally Ca2+-free medium all reduced trans-ACPD's effects.

The calmodulin antagonists N-(6-aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulphonamide (W7) (100 μM) and chlorpromazine (100 μM) diminished the potentiation.

In summary, group I mGluRs selectively facilitate NMDA-depolarization of frog motoneurones via a G-protein, a rise in [Ca2+]i from the presumed generation of phosphoinositides, binding of Ca2+ to calmodulin, and lessening of the Mg2+-produced channel block of the NMDA receptor.

Keywords: N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors; frog; spinal cord motoneurones; trans-(±)-1-amino-1,3-cyclopentanedicarboxylic acid; metabotropic glutamate receptors; G-proteins; open channel block; Mg2+ ions; Ca2+ ions; calmodulin

Introduction

Receptors for the excitatory amino acid neurotransmitter L-glutamate fall into two classes: ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) and metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs). iGluRs are cation-specific ion channel complexes that share fundamental features with other ligand-gated channels. The efficacy of different iGluR agonists has been used to classify iGluRs into three types: N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA); α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-proprionate (AMPA) and kainate (Collingridge & Lester, 1989). L-glutamate, acting at iGluRs, functions as the major excitatory transmitter at synapses in the spinal cord of both mammals and amphibians (Davies et al., 1982). mGluRs consist of a family of excitatory amino acid receptors that use G-proteins and/or various intracellular signal transduction pathways to modify neurotransmission and ion conductances (Pin & Duvoisin, 1995; Conn & Pin, 1997). In contrast to our understanding of iGluRs, how mGluRs function physiologically in the spinal cord is still in dispute. mGluRs may regulate excitatory synaptic transmission mediated by iGluRs in the spinal cord, but data addressing this issue are inconsistent. Some data show, for example, that mGluRs depress monosynaptic excitation of rat spinal motoneurones (an effect believed to be presynaptic and to involve a decrease in the release of L-glutamate from primary afferent terminals), and variably affect polysynaptic excitation produced by activation of C-fibres (Thompson et al., 1992, Boxall et al., 1996; King & Liu, 1997). Other studies report that activation of mGluRs either does not affect, or else increases, NMDA-, AMPA-, or kainate-induced postsynaptic excitations of spinal cord neurones (Cerne & Randic, 1992; Neugebauer et al., 1994; Ugolini et al., 1997; Budai & Larson, 1997).

The present investigations were designed to further our understanding of mGluRs, namely by characterizing the effects on motoneurones in the frog spinal cord when mGluRs are activated. For this purpose we used the isolated frog spinal cord with sucrose gap recording from ventral roots to monitor changes in motoneurone membrane potential. Our results indicate that activation of spinal mGluRs produces changes in evoked reflex activity, in the membrane potential of motoneurones, and in the responses of motoneurones to activation of NMDA receptors. Some of the results have appeared in preliminary form (Hackman et al., 1992, 1994).

Methods

Experiments were performed on adult grass frogs (Rana pipiens, 30–55 g) anaesthetized to the point of unresponsiveness by cooling on crushed ice. After decapitation the brain was immediately destroyed by pithing and a laminectomy performed to remove the spinal cord. The lumbar spinal cord was hemisected sagittally and a hemicord with attached IXth dorsal (DR) and ventral roots (VR) was transferred to a sucrose gap chamber as described previously (Davidoff & Hackman, 1980). The preparation was superfused with Ringer's solution containing (in mM): NaCl 114, KCl 2.0, CaCl2 1.9, NaHCO3 10, and glucose 5.5. In many experiments, Mg2+ (1.0 mM) was added to the medium. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 by bubbling the medium with 95% O2/5% CO2. A Peltier thermoelectric cooling device maintained the temperature at 18°C.

Drugs and agonists were bath-applied by switching the superfusing solution to one containing known concentrations of drugs and agonists. Rapid (1–2 s) solution changes were achieved by the use of a solenoid valve assembly.

For DC recording of electrotonically-conducted changes in the membrane potential of motoneurones, the IXth VR was placed across a 3 mm sucrose gap. Calomel electrodes, connected via agar-Ringer's bridges, measured the difference in potential between the spinal cord bath and the distal end of the VR maintained in a pool of Ringer's solution. The preparation was left ungrounded. After amplification, the signals were recorded using a rectilinear pen writer.

In some experiments, the fibres contained in the IXth dorsal root were stimulated with supramaximal rectangular pulses (15 V, 1.0 ms) delivered via bipolar silver/silver chloride electrodes (Davidoff et al., 1988). The ventral root potential changes evoked by DR stimulation were stored in an IBM AT computer. The integral (the area under the change in ventral root potential produced by dorsal root stimulation in mV.s) was determined by reprogrammed Asyst software, and the potentials were plotted on a laser printer.

The peak amplitude of responses to NMDA and other iGluR agonists was measured in all experiments. All data are expressed as means±s.e.mean. The statistical significance of differences has been assessed by the use of Student's t-test for correlated means.

Drugs

Most drugs were dissolved in Ringer's solution shortly before use to minimize chemical degradation. However, staurosporine, forskolin, and thapsigargin were dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) (<1.0%); arachidonic acid was dissolved in ethanol (<2.0%) before diluting with Ringer's solution. Control solutions containing solvent alone were tested and produced no effects. pH was adjusted when necessary. The following compounds were used in these experiments: 3,5-dimethyl-1-adamantanamine hydrochloride (memantine), trans-(±)-1-amino-1,3-cyclopentanedicarboxylic acid (trans-ACPD), (1S,3R)-1-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (1S,3R ACPD), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-proprionate (AMPA), (RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG), α-methyl-(S)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate (L-MAP4), α-methyl-(2S,3S,4S)-α-(carboxycyclopropyl)-glycine (MCCG), and (RS)-α-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine (MCPG), all purchased from Tocris Cookson; N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) from Cambridge Research Biochemicals; arachidonic acid, chlorpromazine, forskolin, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthane (IBMX), thapsigargin, staurosporine, and N-(2-aminoethyl)-5-isoquinolinesulphonamide HCl (H9) from Research Biochemicals International; kainate, kynurenate, 8-bromo-cyclic AMP, dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO), and phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) from Sigma; and L-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate (L-AP4), N-(6-aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulphonamide (W7), 1,2-bis(O-aminophenoxy) ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetracetic acid acetyl methyl ester (BAPTA-AM), pertussis toxin (PTX), and tetrodotoxin (TTX) from Calbiochem. (+) -5- methyl-10,11- dihydro -5H - dibenzo[a,d] cyclohepten-5,10-imine hydrogen maleate (MK-801) was donated by Merck.

Results

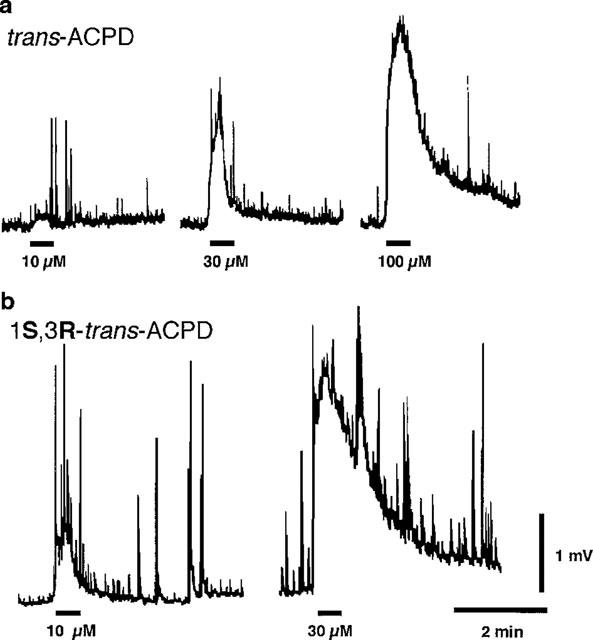

As seen in Figure 1a, short (30 s) applications of the mGluR agonist trans-ACPD (a racemic mixture of (1S,3R)-1-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid and (1R,3S)-1-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid) (10–100 μM) in nominally Mg2+-free medium produced a concentration-dependent depolarization of frog motoneurones (30 μM, 2.9±0.8 mV, n=3). 1S,3R ACPD also depolarized motoneurones, but was more potent than trans-ACPD (30 μM, 5.0±1.3 mV, n=3) (Figure 1b) (cf. Eaton et al., 1993; Boxall et al., 1996; Ugolini et al., 1997). The trans-ACPD-induced depolarizations of motoneurone membranes were reversibly reduced when the spinal cord was exposed to MCPG (240 μM) to 61.0±8.3% of control values (P<0.01, n=3) (not shown).

Figure 1.

trans-ACPD and 1S,3R-ACPD depolarize frog motoneurones. (a) Changes in frog motoneurone membrane potential (electrotonically-conducted along the IXth VR) produced by three concentrations (10, 30 and 100 μM, 30 s applications) of trans-ACPD. (b) Changes in frog motoneurone membrane potential produced by two concentrations (10 and 30 μM) of 1S,3R-ACPD (30 s applications). In these, and in all subsequent records, negativity is indicated by an upward pen deflection and signifies a depolarization of motoneurones whose axons exit from the cord in the IXth VR. The upward ‘spike-like' deflections of the baseline represent spontaneous ventral root potential (VRPs). Applications of trans-ACPD and 1S,3R-ACPD are indicated by bars below the baseline. Traces in a and b were obtained from two different spinal cords. Calibration bars apply to both a and b.

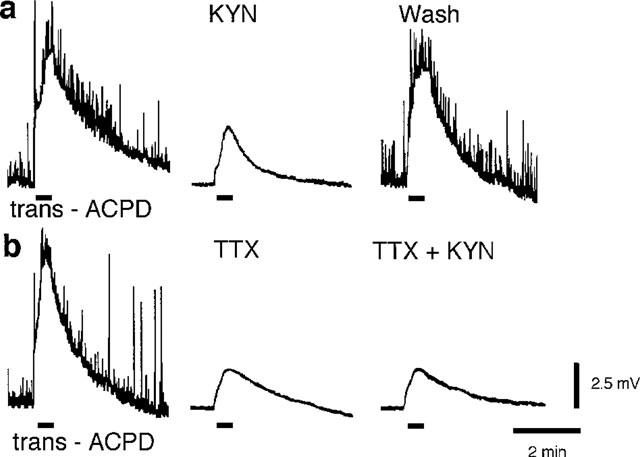

trans-ACPD-evoked potential changes in motoneurones might be caused by activation of iGluRs on motoneurones, produced by an indirect action of trans-ACPD on presynaptic interneurones, or generated by a direct action of trans-ACPD on mGluRs located on motoneurone membranes. To test these hypotheses, TTX and/or kynurenate were added to the superfusate (0 mM Mg2+). Application of kynurenate (1.0 mM), a broad-spectrum antagonist of iGluR-mediated excitations, significantly reduced, but did not abolish, trans-ACPD-motoneurone depolarizations (30.6± 6.3%, P<0.05, n=3) (Figure 2a). Similar effects were produced by TTX in a concentration (0.783 μM) sufficient to block interneuronal firing (34.9±10.1%, P<0.05, n=3) (Figure 2b) (cf. Ugolini et al., 1997). Moreover, when motoneurone depolarizations generated by trans-ACPD were reduced by TTX, subsequent addition of kynurenate had no further effect (TTX+kynurenate, 102.2% of trans-ACPD-responses in TTX alone, n=2).

Figure 2.

trans-ACPD-induced motoneurone depolarizations are blocked by kynurenate (KYN) and tetrodotoxin (TTX). (a) Application of trans-ACPD (30 μM, 30 s) before, during, and after addition of kynurenate (1.0 mM, 30 min) to Ringer's solution. (b) Depolarization produced by trans-ACPD (30 μM, 30 s) is diminished by TTX (0.783 μM). Subsequent addition of kynurenate (1.0 μM) had no further effect. Applications of trans-ACPD are indicated by bars below the baseline. Traces in a and b were obtained from two different spinal cords. Calibration bars apply to both a and b.

trans-ACPD and reflex responses

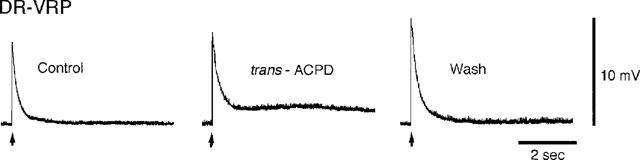

As seen in Figure 3, supramaximal stimulation of the dorsal root (DR) of the frog spinal cord bathed in Ringer's solution containing 1.0 mM Mg2+ generated early and late polysynaptic potentials in motoneurones that were electrotonically conducted along the VR (ventral root potentials, VRPs). Application of trans-ACPD (30 μM) significantly potentiated polysynaptic reflex responses, particularly the longer-latency components (239.6±38.9% of control VRP area, P<0.05, n=5). The effects of trans-ACPD were partially reversible upon returning the cord to trans-ACPD-free Ringer's solution.

Figure 3.

trans-ACPD potentiates polysynaptic reflexes in the frog spinal cord. Traces are ventral root potentials (VRPs) produced by single supramaximal shocks (arrows) applied to the afferent fibres in the sciatic nerve. Control VRP, VRP recorded during exposure to trans-ACPD (30 μM), and VRP obtained after return to normal Ringer's solution are shown. The experiment was carried out in Ringer's solution containing 1.0 mM Mg2+.

Activation of mGluRs and NMDA-induced motoneurone depolarizations: the role of NMDA channel blockers

We next sought to discern whether or not changes in the postsynaptic responsiveness of spinal neurones to excitatory amino acid agonists might account for some of trans-ACPD's facilitatory actions on reflex transmission. How trans-ACPD might affect the sensitivity of postsynaptic motoneuronal membranes to endogenously released excitatory amino acid transmitters that activate iGluRs was evaluated by determining the effects of trans-ACPD on motoneurone depolarizations evoked by short (5–10 s) applications of the selective iGluR agonists NMDA (100 μM), AMPA (10 μM), and kainate (30 μM). This group of experiments (and all following experiments) were conducted in medium containing 0.783 μM TTX to reduce indirect actions of ACPD.

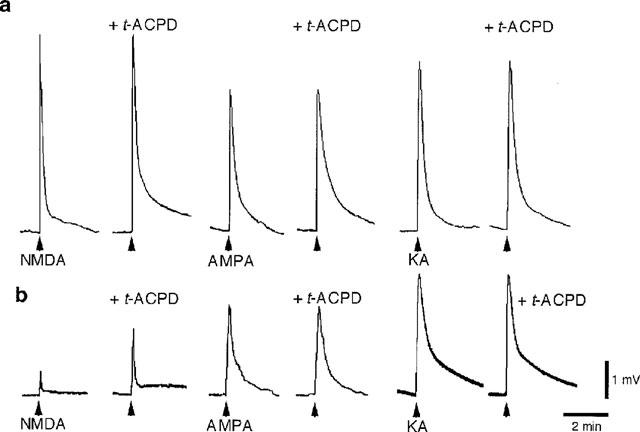

As seen in Figure 4a, trans-ACPD (30 μM) had no effect on the depolarizations produced by iGluR agonists in nominally Mg2+-free Ringer's solution (NMDA: 102.3±3.0% of control, n=6; AMPA: 98.6±3.5%, n=3; kainate: 99.2±3.3%, n=3) (cf. Harvey & Collingridge, 1993). In contrast, in the presence of a ‘physiological' concentration of Mg2+ (1.0 mM in amphibians) (Davidoff et al., 1988), trans-ACPD (30 μM) significantly potentiated NMDA-induced motoneurone depolarizations (100 μM NMDA: 183.5±22.8% of control, P<0.05, n=6; 300 μM NMDA: 174.3±25.5%, P<0.05, n=6) (Figure 4b). Maximal potentiation of NMDA responses was seen within 1 min after beginning perfusion with Mg2+-Ringer's solution containing trans-ACPD; the potentiation lasted for the duration of the trans-ACPD application. The effect of trans-ACPD was slowly reversible after return to normal medium. The presence of Mg2+ in the Ringer's solution did not change the inability of trans-ACPD (30 μM) to facilitate motoneurone depolarizations evoked by application of AMPA (10 μM, 100%, n=2) or kainate (30 μM, 98.5%, n=2).

Figure 4.

trans-ACPD facilitates NMDA-evoked motoneurone depolarizations in Ringer's solution containing Mg2+. (a) Applications of NMDA (100 μM, 10 s), AMPA (10 μM, 10 s), and kainate (KA) (30 μM, 10 s) in nominally Mg2+-free Ringer's solution before and after exposure to trans-ACPD (30 μM). (b) Same experiment carried out in another spinal cord in Ringer's solution containing 1.0 mM Mg2+. Both experiments were performed in Ringer's solution containing TTX (0.783 μM). Applications of iGluR agonists are indicated by arrows below the baseline. Calibration bars apply to both a and b.

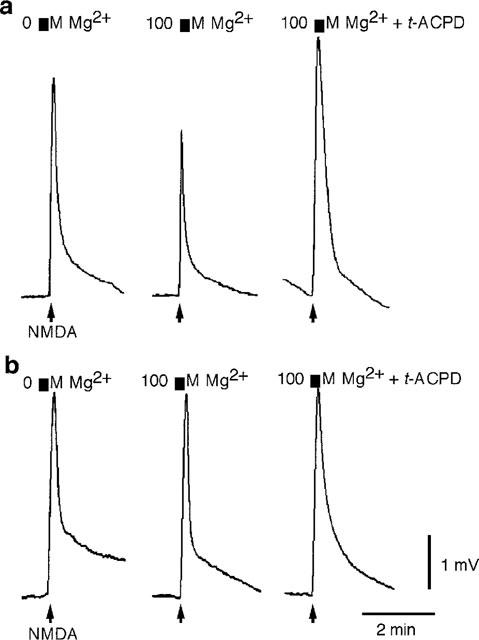

The effects of various concentrations of extracellular Mg2+ on the facilitation of NMDA-responses by trans-ACPD was examined. In the frog spinal cord trans-ACPD did not facilitate NMDA-responses until a threshold Mg2+ concentration of 100 μM was reached. In some cords, a threshold concentration of Mg2+ added to the Ringer's solution (100–250 μM) reduced NMDA responses (79.5±7.8% of control values in 0 mM Mg2+, n=3), and in these cords trans-ACPD (30 μM) potentiated NMDA (100 μM) responses (138.3±23.4% of control values in Mg2+, n=3) (Figure 5a). In contrast, in other cords these same concentrations of Mg2+ did not diminish NMDA responses (98.5±1.4% of control values in 0 mM Mg2+, n=4); nor was facilitation seen (97.9±2.7% of control values in Mg2+, n=4) (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

trans-ACPD potentiates NMDA responses if the concentration of extracellular Mg2+ is sufficient to produce channel block. (a) trans-ACPD (t-ACPD) (30 μM) potentiates NMDA responses in a cord exposed to 100 μM Mg2+. Note the decreased amplitude of the NMDA response when the Ringer's contained 100 μM Mg2+. (b) trans-ACPD (30 μM) had no effect on NMDA-induced motoneurone depolarization in a second spinal cord exposed to 100 μM Mg2+; nor did 100 μM Mg2+ affect NMDA-responses. Both experiments were performed in Ringer's solution containing TTX (0.783 μM). Calibration bars apply to both a and b.

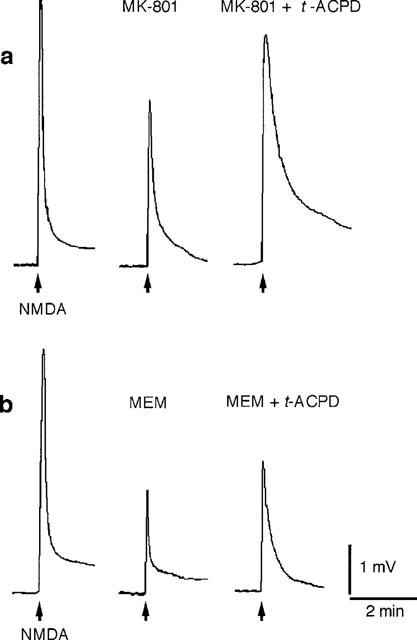

Mg2+ binds to the NMDA receptor channel opened by activation of the receptor (MacDonald & Nowak, 1990). In the presence of other NMDA open channel blockers – MK-801 (3–6 μM) and memantine (10–20 μM) – trans-ACPD also significantly potentiated NMDA responses, but the potentiation was not as marked as with Mg2+ (Figure 6 and Table 1). It should be noted that depolarization (1.5 mV) of motoneurones by elevation of extracellular K+ (2.5 mM) did not mimic the facilitatory effects of trans-ACPD on NMDA responses (88.2%±4.0; n=4). Therefore, the trans-ACPD-induced depolarization of motoneurones bathed in Ringer's solution containing 1.0 mM Mg2+ is presumably not responsible for the facilitation of NMDA effects.

Figure 6.

trans-ACPD-induced potentiation of NMDA responses is present in spinal cords exposed to NMDA receptor channel blockers. (a) Spinal cord exposed to MK-801 (6 μM). (b) Spinal cord exposed to memantine (MEM) (10 μM). Both experiments were performed in Ringer's solution containing TTX (0.783 μM). Applications of NMDA (100 μM, 5 s) are indicated by arrows below the baseline. Calibration bars apply to both a and b.

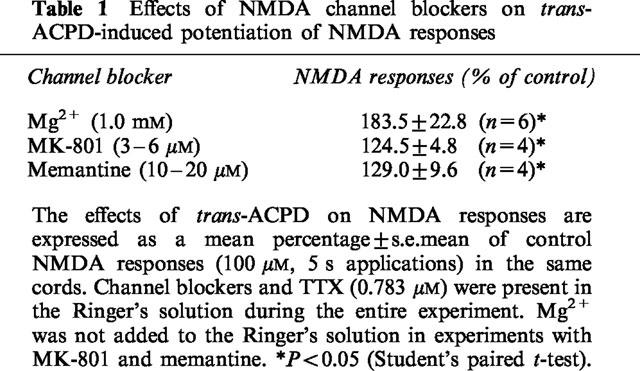

Table 1.

Effects of NMDA channel blockers on trans-ACPD-induced potentiation of NMDA responses

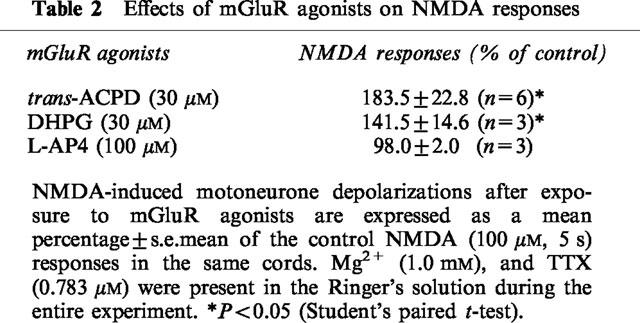

mGluR subtypes and potentiation of NMDA-induced responses

To determine which mGluR subtypes mediated the potentiation of NMDA responses, the effects of several selective agonists and antagonists of mGluRs were examined in spinal cords superfused with medium containing 1.0 mM Mg2+. In a manner similar to that of trans-ACPD, the selective group I mGluR agonist DHPG potentiated NMDA responses, while the group III agonist L-AP4 was without effect (Table 2). The potentiation of NMDA-motoneurone responses by trans-ACPD (30 μM) was significantly blocked by the non-selective mGluR antagonist MCPG (Table 3). In contrast, the group II antagonist MCCG and the group III antagonist L-MAP4 did not significantly alter the actions of trans-ACPD on NMDA responses (Table 3).

Table 2.

Effects of mGluR agonists on NMDA responses

Table 3.

Effects of mGluR antagonists on trans-ACPD-induced potentiation of NMDA responses

G-proteins and trans-ACPD-induced effects on NMDA responses

The premise that a G-protein is involved in trans-ACPD's actions on NMDA responses was investigated by incubating hemisected frog spinal cords in standard Ringer's solution either with or without pertussis toxin (PTX) (3–6 ng ml−1) for 36 h at 4°C. In spinal cords incubated with PTX, the ability of trans-ACPD (30 μM) to facilitate NMDA responses in the presence of 1.0 mM Mg2+ was significantly reduced (94.5±7.8%, n=3) when compared to spinal cords incubated in Ringer's solution without PTX (141.1±9.3%, P<0.01, n=4).

Second messengers, internal Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i), and the facilitatory actions of trans-ACPD

Activation of group I mGluRs is reported to lead to the activation of protein kinase C and the formation of phosphoinositides. To evaluate the possible involvement of protein kinase C in the potentiation of NMDA by trans-ACPD, we used two potent inhibitors of protein kinase C – staurosporine (2.0 μM) and H9 (77 μM) (Hidaka & Kobayashi, 1992) – and a potent activator of protein kinase C, PMA (phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate, 5.0 μM). Staurosporine and H9 did not significantly affect the facilitatory effect of trans-ACPD (30 μM) on NMDA responses, and PMA (applied for 30 min) neither mimicked, nor reduced, the effect of trans-ACPD (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effects of various treatments on trans-ACPD-induced potentiation of NMDA responses

The production of phosphoinositides results in the release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum and the influx of Ca2+ from extracellular medium. To investigate whether the release of Ca2+ from intracellular loci and a subsequent increase in [Ca2+]i is required for the facilitation of NMDA responses by trans-ACPD, thapsigargin (0.1 μM) (which depletes most intracellular Ca2+) and BAPTA-AM (50 μM) (which buffers elevations of [Ca2+]i) were applied to frog spinal cords in different experiments. While neither compound had a direct effect on NMDA responses, both of them prevented the potentiation of NMDA responses by trans-ACPD (Table 4). They had no significant effect on NMDA responses. Further evidence that a Ca2+-dependent process was involved in the facilitation of NMDA responses was obtained by exposing spinal cords to nominally Ca2+-free medium (containing 1.0 mM Mg2+). This treatment did not affect NMDA responses (92.6±4.6% of control responses in 1.9 mM Ca2+, n=3) but blocked potentiation of NMDA responses by trans-ACPD (30 μM) (Table 4).

Ca2+ ions possess numerous intracellular targets including the Ca2+-binding protein calmodulin. The facilitation of NMDA responses by trans-ACPD (30 μM) was significantly reduced by the calmodulin antagonists W7 (100 μM) and chlorpromazine (100 μM) (Table 4).

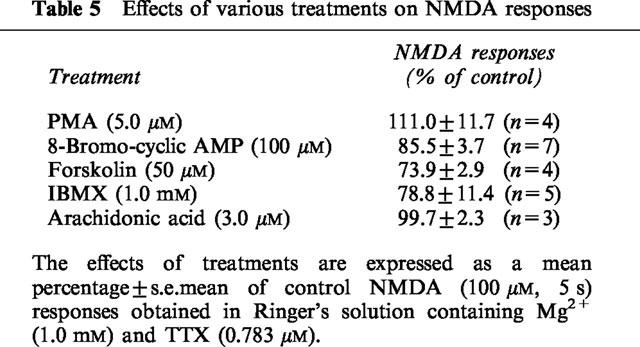

mGluRs use intracellular signal transduction pathways other than the one involving phosphoinositides to modify neurotransmission and ion conductances (Conn & Pin, 1997). To determine whether or not the facilitation of NMDA-depolarizations of motoneurones caused by mGluR activation was linked to cyclic AMP-coupled mechanisms, we evaluated the effects of agents known to increase the effective intracellular concentration of cyclic AMP. As Table 5 indicates, high concentrations of 8-bromo-cyclic AMP, forskolin and IBMX did not potentiate NMDA-induced motoneurone depolarizations. Arachidonic acid was also without effect on NMDA responses (Table 5).

Table 5.

Effects of various treatments on NMDA responses

Discussion

Polysynaptic reflexes in the frog spinal cord are presumed to be mediated by the synaptic release of excitatory amino acids and the subsequent activation of iGluRs, including NMDA receptors, on interneurones and motoneurones (Davies et al., 1982). The present study provides evidence that activation of specific mGluRs augments reflex effects on frog spinal motoneurones. In addition, the consequences of mGluR activation on reflexes appear to be mediated, at least in part, by a postsynaptic action at NMDA receptors.

Our results show that trans-ACPD – which activates mGluRs – facilitated the polysynaptic components of segmental spinal reflexes evoked by supramaximal stimulation of afferent fibres in the frog spinal cord when the cords are bathed in Ringer's solution containing Mg2+ ions. The same concentrations of trans-ACPD that significantly increase reflex activity selectively potentiate the motoneurone responses produced by applications of NMDA. And in contrast to previous reports in both in vivo and in vitro mammalian spinal cord preparations, our results show that activation of mGluRs in the frog spinal cord had no effect on motoneurone depolarizations mediated by AMPA and kainate (cf. Cerne & Randic, 1992; Neugebauer et al., 1994; Ugolini et al., 1997). The action of trans-ACPD on NMDA responses, therefore, appears to be selective. A second site of action for trans-ACPD at a presynaptic locus on afferent fibre terminals and/or interneurones to block the release of excitatory amino acids is not, however, precluded by our observations.

The effects of trans-ACPD on NMDA receptors appear to depend upon activation of specific mGluRs. There are at least eight major mGluRs (mGluR1-8) divisible into three groups (I, II and III) on the basis of sequence homology, pharmacological characteristics, and coupling to intracellular transduction mechanisms (Conn & Pin, 1997). In the present experiments, activation of group I mGluRs appear to cause trans-ACPD's effects on NMDA responses on frog motoneurones. This idea is supported by the observations that trans-ACPD's actions on NMDA-depolarizations were significantly blocked by the non-selective antagonist MCPG (Kemp et al., 1994), but were not affected either by the selective group II antagonist MCCG (Jane et al., 1994) or by the selective group III antagonist MAP4 (Jane et al., 1994). Moreover, the selective group I mGluR agonist DHPG (Ito et al., 1992) facilitated NMDA-evoked motoneurone depolarizations, while L-AP4, an agonist selective for group III mGluRs had no effect on NMDA-motoneurone responses (Jane et al., 1994).

G-Proteins and potentiation of NMDA responses by trans-ACPD

Previous studies have shown the effects of activating group I mGluRs to be both insensitive and sensitive to the actions of PTX (Pin & Duvoisin, 1995). PTX prevents the interaction of receptors with several G-proteins (including Go and Gi) by ADP-ribosylating their α subunits (Gilman, 1987). PTX blockade of a receptor-mediated event suggests that a G-protein (either Go or Gi) is involved in mediation of the receptor's actions. In the present investigation, activation of mGluRs by trans-ACPD causing facilitation of NMDA responses was found to be sensitive to PTX. The data, therefore, support the role of a G-protein as a mediator of the actions of trans-ACPD in the facilitation of NMDA-responses in frog motoneurones.

Second messengers, [Ca2+]i and the potentiating actions of trans-ACPD

In most systems, group I mGluRs stimulate phospholipase C to cleave membrane phospholipids yielding inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG) (Conn & Pin, 1997). IP3 causes a rise in [Ca2+]i by mobilizing Ca2+ from non-mitochondrial internal stores and by increasing Ca2+ influx from extracellular medium (Mayer & Miller, 1990; Meldolesi et al., 1991). In the present experiments, three treatments which would be expected either to reduce [Ca2+]i or to prevent elevations of [Ca2+]i were tested for their effects on trans-ACPD facilitation of NMDA responses. Thapsigargin depletes most intracellular Ca2+ by inhibiting Ca2+/ATPase in intracellular compartments and preventing refilling of intracellular stores (Thastrup et al., 1990). BAPTA-AM (50 μM) is a membrane-permeable Ca2+ chelator that acts to buffer elevations of [Ca2+]i (Niesen et al., 1991). Reduction of extracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]o) presumably depletes [Ca2+]i and prevents Ca2+ influx. Because thapsigargin, BAPTA-AM, and perfusion with nominally Ca2+-free Ringer's solution prevented trans-ACPD from facilitating NMDA responses, an elevation of [Ca2+]i appears necessary for the facilitatory actions of mGluRs in frog spinal cord. Alternatively, because neurotransmitter-activated phosphoinositide hydrolysis is reduced by low [Ca2+]i procedures which reduce [Ca2+]i also affect the actions of trans-ACPD by preventing the formation of IP3 (Kendall & Nahorski, 1984).

How changes in [Ca2+]i determine NMDA responses is unclear. Several studies indicate that NMDA receptors are transiently inactivated by increased [Ca2+]i (Legendre et al., 1993; Rosenmund et al., 1995). In contrast, elevation of [Ca2+]i resulting from the formation of inositol phosphate derivatives has been postulated to underlie the potentiation of NMDA responses produced by several neurotransmitters (Markram & Segal, 1992; Kinney & Slater, 1993; Rahman & Neuman, 1996a). Analysis is complicated by findings that intracellular Ca2+ does not consist of a single homogeneous pool. In neurones there are at least two pharmacologically distinguishable pools of readily releasable Ca2+: the IP3-releasable stores and the Ca2+-induced Ca2+ stores (Henzi & McDermott, 1992). It may well be that different pools of intracellular Ca2+ affect NMDA receptors in dissimilar ways. In this regard, we have previously shown that caffeine – which induces release of Ca2+ from the Ca2+-induced release stores – does in fact reduce NMDA responses in frog motoneurones (Hackman et al., 1994).

The effects of changing Ca2+ concentrations of Ca2+ ions on frog motoneurone-NMDA responses may involve the ubiquitous, multifunctional Ca2+-binding protein calmodulin. Both W-7 and chlorpromazine, two potent calmodulin inhibitors reduced trans-ACPD-potentiation of frog motoneurone NMDA responses (Tanaka et al., 1982; Weiss et al., 1982). Calmodulin binds directly to the NR1 subunit of the NMDA receptor complex in a Ca2+-dependent manner (Ehlers et al., 1996). Reports vary, however, on how calmodulin affects the NMDA receptor. There are findings that calmodulin binding to the NMDA receptor reduces the probability that the NMDA channel will open (Ehlers et al., 1996). CaM-Kinase II (type II calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase), however, phosphorylates both recombinant and native glutamate receptors in several in vitro systems thereby potentiating responses to NMDA in spinal cord neurones (McGlade-McCulloh et al., 1993; Kolaj et al., 1994).

In addition to generating IP3 when group I mGluRs stimulate phospholipase C, the process yields DAG, a substance known to activate protein kinase C. Protein kinase C may play a role in mGluR-mediated facilitation of NMDA responses, although reports differ (cf. Kelso et al., 1992; Harvey & Collingridge, 1993; Kinney & Slater, 1993; Rahman & Neuman, 1996a). Our studies found that the protein kinase C antagonists staurosporine and H9 did not block the potentiation of NMDA responses by trans-ACPD and PMA did not mimic the effects of trans-ACPD. These results argue against a mandatory role for protein kinase C in mediating the facilitatory actions of trans-ACPD on NMDA responses in frog motoneurones. The possibility exists, however, that some of trans-ACPD's actions on frog motoneurones result from activation of staurosporine- and H9-resistant isoforms of protein kinase C.

mGluRs have the potential to initiate several other biochemical responses in target neurones; among these are changes in cyclic AMP and arachidonic acid levels (Conn et al., 1997). Moreover, cyclic AMP and arachidonic acid are reported to augment NMDA responses (Miller et al., 1992; Cerne et al., 1993). Our results, however, do not find changes in the concentration of these compounds causative in trans-ACPD-facilitated NMDA responses. Rather, we found that elevation of intracellular levels of cyclic AMP by 8-bromo-cyclic AMP (a membrane-permeant cyclic AMP analogue which elevates levels of cyclic AMP), forskolin (a direct activator of the catalytic subunit of adenylyl cyclase), or IBMX (an inhibitor of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase activity) did not mimic the facilitatory effects of trans-ACPD on NMDA responses. Similarly, arachidonic acid was without effect on NMDA responses. These results agree with reports concerning hippocampal and neocortical neurones (Harvey & Collingridge, 1993; Rahman & Neuman, 1996a).

NMDA channel block and facilitation of NMDA responses by trans-ACPD

Although activation of mGluRs has been reported to potentiate NMDA responses in neurones bathed in nominally Mg2+-free medium (Cerne & Randic, 1992; Harvey & Collingridge, 1993), the trans-ACPD potentiation of NMDA-induced responses in frog motoneurone required a concentration of at least 100 μM Mg2+ ions in the Ringer's solution. Mg2+ ions are not ordinarily added to frog Ringer's solution, but frog cerebrospinal fluid contains the cation in a concentration of 0.92 mM (Davidoff et al., 1988). We assume that the interstitial fluid surrounding frog neurones in vivo contains Mg2+ in approximately that concentration as well.

One might posit that the ineffectiveness of trans-ACPD in Mg2+-free Ringer's solution reflects the G-protein-coupled receptor's need for cytosolic Mg2+ ions in order to function effectively (El-Beheiry & Puil, 1990; Rahman & Neuman, 1996b). But, in the present experiments the NMDA channel blockers memantine and MK-801 were able to substitute in large measure for Mg2+ ions. Mg2+, MK-801, and memantine all limit functioning of the NMDA receptors by binding to sites within the open ion channel operated by activation of the NMDA receptor (Huettner & Bean, 1988; MacDonald & Nowak, 1990; Blanpied et al., 1997). Our data are compatible with the hypothesis that trans-ACPD potentiates NMDA responses in frog motoneurones by reducing channel block of the NMDA receptor.

Activation of mGluRs and motoneurone depolarizations

It has been previously demonstrated that trans-ACPD depolarizes motoneurones in the rat spinal cord (Jane et al., 1994; King & Liu, 1997). This is also the case in the frog where we found the depolarization was significantly reduced, but not eliminated, by either TTX (in a concentration sufficient to eliminate regenerative activity and firing of spinal interneurones and primary afferent fibres) or by the non-specific iGluR antagonist kynurenate (in a concentration sufficient to block responses mediated by iGluRs). Moreover, the ability of TTX and kynurenate to reduce trans-ACPD-induced depolarizations was not additive. These findings suggest that a proportion of the trans-ACPD-depolarization occurs indirectly, depends upon the discharge of interneurones and/or primary afferent fibres, and may be caused by the release of L-glutamate and the subsequent activation of iGluRs. In part, the trans-ACPD-induced depolarization appears to result from direct effects of the agonist on motoneurone membranes. In other systems, membrane depolarization caused by activation of mGluRs appears to be the consequence either of activation of a non-specific cationic conductance or of inhibition of various different K+ conductances (Charpak et al., 1990; Crépel et al., 1994; Guérineau et al., 1994). In the frog spinal cord, however, we cannot yet say precisely how trans-ACPD produces the direct component of motoneurone depolarization.

Taken together, the results reported here suggest that the facilitation of NMDA-induced depolarizations of frog motoneurones by trans-ACPD is caused by a mechanism that encompasses: (1) activation of group I mGluRs; (2) activation of a G-protein; (3) a rise in [Ca2+]i presumably resulting from production of phosphoinositides; (4) binding of Ca2+ to calmodulin and (5) reduction of the open channel block of the NMDA receptor produced by physiological concentrations of Mg2+ ions.

Acknowledgments

Supported by U.S.P.H.S. grants NS 37946, NS 30600, NIH 5T32NS07044, and the Office of Research and Development (R.&D.) Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs (V.A.). We wish to thank David Meinbach, Vidia Prakasam, Maria Montes de Oca, Jafri Rambeau, Mohammed Fasihi and Phuonglien Nguyen for their help in performing some of these experiments.

Abbreviations

- 1S,3R-ACPD

(1S,3R)-1-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-proprionate

- BAPTA-AM

1,2-bis(O-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetracetic acid acetyl methyl ester

- 8-bromo-cyclic AMP

8-bromo-3′5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- cyclic AMP

3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DHPG

(RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine

- DMSO

dimethyl sulphoxide

- DR

dorsal root

- DR-VRP

dorsal root-ventral root potential

- G-protein

guanosine triphosphate-binding protein

- H9

N-[2-(aminoethyl)-5-isoquinolinesulphonamide HCl

- IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- iGluR

ionotropic glutamate receptor

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate

- KA

kainate

- KYN

kynurenate

- L-AP4

L(+)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid

- L-MAP4

α-methyl-(S)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate

- MCCG

α-methyl-(2S,3S,4S)-α-(carboxycyclopropyl)-glycine

- MCPG

(RS)-α-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine

- MEM

memantine, 3,5-dimethyl-1-adamantanamine hydrochloride

- mGluR

metabotropic glutamate receptor

- MK-801

(+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5,10-imine hydrogen maleate

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- PMA

phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate

- PTX

pertussis toxin

- trans-ACPD

(±)-1-amino-trans-1,3-cyclopentane-dicarboxylic acid

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- VR

ventral root

- W7

N-(6-aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulphonamide.

References

- BLANPIED T.A., BOECKMAN F.A., AIZENMAN E., JOHNSON J.W. Trapping channel block of NMDA-activated responses by amantadine and memantine. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;77:309–323. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOXALL S.J., THOMPSON S.W.N., DRAY A., DICKENSON A.H., URBAN L. Metabotropic glutamate receptor activation contributes to nociceptive reflex activity in the rat spinal cord in vitro. Neuroscience. 1996;74:13–20. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUDAI D., LARSON A.A. The involvement of metabotropic glutamate receptors in sensory transmission in dorsal horn of the rat spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1997;83:571–580. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00390-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CERNE R., RANDIC M. Modulation of AMPA and NMDA responses in rat spinal dorsal horn neurons by trans-1-aminocyclopentane-1, 3-dicarboxylic acid. Neurosci. Lett. 1992;144:180–184. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90745-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CERNE R., RUSKIN K.I., RANDIC M. Enhancement of the N-methyl-D-aspartate response in spinal dorsal horn neurons by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Neurosci. Lett. 1993;161:124–128. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90275-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHARPAK S., GÄHWILER B.H., DO K.Q., KNÖPFEL T. Potassium conductances in hippocampal neurones blocked by excitatory amino acid transmitters. Nature. 1990;347:765–767. doi: 10.1038/347765a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLINGRIDGE G.L., LESTER R.A. Excitatory amino acid receptors in the vertebrate central nervous system. Pharmacol. Rev. 1989;40:143–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONN P.J., PIN J.-P. Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1997;37:205–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRÉPEL V., ANIKSZTEJN L., BEN-ARI Y., HAMMOND C. Glutamate metabotropic receptors increase a Ca2+-activated nonspecific cationic current in CA1 hippocampal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1994;72:1561–1569. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.4.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIDOFF R.A., HACKMAN J.C. Hyperpolarization of frog primary afferent fibres caused by activation of a sodium pump. J. Physiol. 1980;302:297–309. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIDOFF R.A., HACKMAN J.C., HOLOHEAN A.M., VEGA J.L., ZHANG D.X. Primary afferent fibre activity, putative excitatory transmitters and extracellular potassium in the frog spinal cord. J. Physiol. 1988;397:291–306. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIES J., EVANS R.H., JONES A.W., SMITH D.A.S., WATKINS J.C. Differential activation and blockade of excitatory amino acid receptors in the mammalian and amphibian central nervous systems. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1982;72C:211–224. doi: 10.1016/0306-4492(82)90086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EATON S.A., JANE D.E., JONES P.L.STJ., PORTER R.H.P., POOK P.C.-K., SUNTER D.C., UDVARHELYI P.M., ROBERTS P.J., SALT S.A., WATKINS J.C. Competitive antagonism at metabotropic glutamate receptors by (S)-4-carboxyphenyl-glycine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;244:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(93)90028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EHLERS M.D., ZHANG S., BERNHARDT J.P., HUGANIR R.L. Inactivation of NMDA receptors by direct interaction of calmodulin with the NR1 subunit. Cell. 1996;84:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EL-BEHEIRY H., PUIL E. Effects of hypomagnesia on transmitter actions in neocortical slices. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1990;101:1006–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14197.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILMAN A. G proteins: transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1987;56:615–649. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUÉRINEAU N.C., GÄHWILER B.H., GERBER U. Reduction of resting K+ current by metabotropic glutamate and muscarinic receptors in rat CA3 cells: mediation by G-proteins. J. Physiol. 1994;474:27–33. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp019999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HACKMAN J.C., HOLOHEAN A.M., DAVIDOFF R.A. Effect of metabotropic receptor activation on the frog spinal cord. The Pharmacologist. 1992;34:155. [Google Scholar]

- HACKMAN J.C., HOLOHEAN A.M., DAVIDOFF R.A. A comparison of the actions of ACPD and caffeine on the spinal cord. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 1994;20:730. [Google Scholar]

- HARVEY J., COLLINGRIDGE G.L. Signal transduction pathways involved in the acute potentiation of NMDA responses by 1S,3R-ACPD in rat hippocampal slices. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;109:1085–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HENZI V., MACDERMOTT A.B. Characteristics and function of Ca2+ and inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate-releasable stores of Ca2+ in neurons. Neuroscience. 1992;46:251–273. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIDAKA H., KOBAYASHI R. Pharmacology of protein kinase inhibitors. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1992;32:377–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.32.040192.002113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUETTNER J.E., BEAN B.P. Block of N-methyl-D-aspartate-activated current by the anticonvulsant MK-801: selective binding to open channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988;85:1307–1311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO I., KOHDA A., TANABE S., HIROSE E., HAYASHI M., MITSUNGA S., SUGIYAMA H. 3,5-Dihydroxyphenylglycine is a potent agonist of metabotropic glutamate receptors. NeuroReport. 1992;3:1013–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANE D.E., JONES P.L.ST.J., POOK P.C.-K., TSE H.-W., WATKINS J.C. Actions of two new antagonists showing selectivity for different sub-types of metabotropic glutamate receptor in the neonatal rat spinal cord. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;112:809–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KELSO S.R., NELSON T.E., LEONARD J.P. Protein kinase C-mediated enhancement of NMDA currents by metabotropic glutamate receptors in Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol. 1992;449:705–718. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEMP M., ROBERTS P., POOK P.C.-K., JANE D.E., JONES A., JONES PL. STJ., SUNTER D.C., UDVARHELYI P.M., WATKINS J.C. Antagonism of presynaptically mediated depressant responses and cyclic AMP-coupled metabotropic glutamate receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;266:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(94)90109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KENDALL D.A., NAHORSKI S.R. Inositol phospholipid hydrolysis in rat cerebral cortical slices. II. Calcium requirement. J. Neurochem. 1984;42:1388–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb02799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KING A.E., LIU X.H. Dual action of metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists on neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission in spinal ventral horn neurons in vitro. Neuropharmacology. 1997;35:1673–1680. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KINNEY G.A., SLATER N.T. Potentiation of NMDA receptor-mediated transmission in turtle cerebellar granule cells by activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors. J. Neurophysiol. 1993;69:585–594. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.2.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOLAJ M., CERNE R., CHENG G., BRICKEY D.A., RANDIC M. Alpha subunit of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase enhances excitatory amino acid and synaptic responses of rat dorsal horn neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2525–2531. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.5.2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEGENDRE P., ROSENMUND C., WESTBROOK G.L. Inactivation of NMDA channels on hippocampal neurons by intracellular calcium. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:674–684. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00674.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACDONALD J.F., NOWAK L.M. Mechanisms of blockade of excitatory amino acid receptor channels. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1990;11:167–172. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90070-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARKRAM H., SEGAL M. The inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate pathway mediates cholinergic potentiation of rat hippocampal neuronal responses to NMDA. J. Physiol. 1992;447:513–533. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAYER M.L., MILLER R.J. Excitatory amino acid receptors, second messengers and regulation of intracellular Ca2+ in mammalian neurons. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1990;11:254–260. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCGLADE-MCCULLOH E., YAMAMOTO H., TAN E., BRICKEY D.A., SODERLING T.R. Phosphorylation and regulation of glutamate receptors by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Nature. 1993;362:640–642. doi: 10.1038/362640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MELDOLESI J., CLEMENTI E., FASOLATO C., ZACCHETTI D., POZZAN T. Ca2+ influx following receptor activations. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1991;12:289–292. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90577-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER B., SARANTIS M., TRAYNELIS S.F., ATTWELL D. Potentiation of NMDA receptor currents by arachidonic acid. Nature. 1992;355:722–725. doi: 10.1038/355722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEUGEBAUER V., LÜCKE T., SCHAIBLE H.-G. Requirement of metabotropic glutamate receptors for the generation of inflammation-evoked hyperexcitability in rat spinal cord neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1994;6:1179–1186. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIESEN C., CHARLTON M.P., CARLEN P.L. Postsynaptic and presynaptic effects of the calcium chelator BAPTA on synaptic transmission in rat hippocampal dentate granule neurons. Brain Res. 1991;555:319–325. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90358-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIN J.-P., DUVOISIN R. The metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00129-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAHMAN S., NEUMAN R.S. Characterization of metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated facilitation of N-methyl-D-aspartate depolarization of neocortical neurones. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996a;117:675–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAHMAN S., NEUMAN R.S. Action of 5-hydroxytryptamine in facilitating N-methyl-D-aspartate depolarization of cortical neurones mimicked by calcimycin, cyclopiazonic acid and thapsigargin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996b;119:877–884. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSENMUND C., FELTZ A., WESTBROOK G.L. Calcium-dependent inactivation of synaptic NMDA receptors in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1995;73:427–430. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.1.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANAKA T., OHMURA T., YAMAKADO T., HIDAKA H. Two types of calcium-dependent protein phosphorylations modulated by calmodulin antagonists. Naphthalenesulfonamide derivatives. Mol. Pharmacol. 1982;22:408–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THASTRUP O., CULLEN P.J., DROBAK B.K., HANLEY M.R., DANNIE P.S. Thapsigargin, a tumor promotor, discharges intracellular calcium stores by specific inhibition of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:2466–2470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMPSON S.W.N., GERBER G., SIVILOTTI L.G., WOOLF C.J. Long duration ventral root potentials in the neonatal rat spinal cord in vitro: the effects of ionotropic and metabotropic excitatory amino acid receptor antagonists. Brain Res. 1992;595:87–97. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91456-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UGOLINI A., CORSI M., BORDI F. Potentiation of NMDA and AMPA responses by group I mGluR in spinal cord motoneurons. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1047–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEISS B., PROZIALECK W.C., WALLACE T.L. Interaction of drugs with calmodulin. Biochemical, pharmacological and clinical applications. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1982;31:2217–2226. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(82)90104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]