Abstract

Arachidonic acid (0.01–1μM) induced relaxation of precontracted rings of rabbit saphenous vein, which was counteracted by contraction at concentrations higher than 1μM. Concentrations higher than 1μM were required to induce dose-dependent contraction of vena cava and thoracic aorta from the same animals.

Pretreatment with a TP receptor antagonist (GR32191B or SQ29548, 3μM) potentiated the relaxant effect in the saphenous vein, revealed a vasorelaxant component in the vena cava response and did not affect the response of the aorta.

Removal of the endothelium from the venous rings, caused a 10 fold rightward shift in the concentration-relaxation curves to arachidonic acid. Whether or not the endothelium was present, the arachidonic acid-induced relaxations were prevented by indomethacin (10μM) pretreatment.

In the saphenous vein, PGE2 was respectively a 50 and 100 fold more potent relaxant prostaglandin than PGI2 and PGD2. Pretreatment with the EP4 receptor antagonist, AH23848B, shifted the concentration-relaxation curves of this tissue to arachidonic acid in a dose-dependent manner.

In the presence of 1μM arachidonic acid, venous rings produced 8–10 fold more PGE2 than did aorta whereas 6keto-PGF1α and TXB2 productions remained comparable.

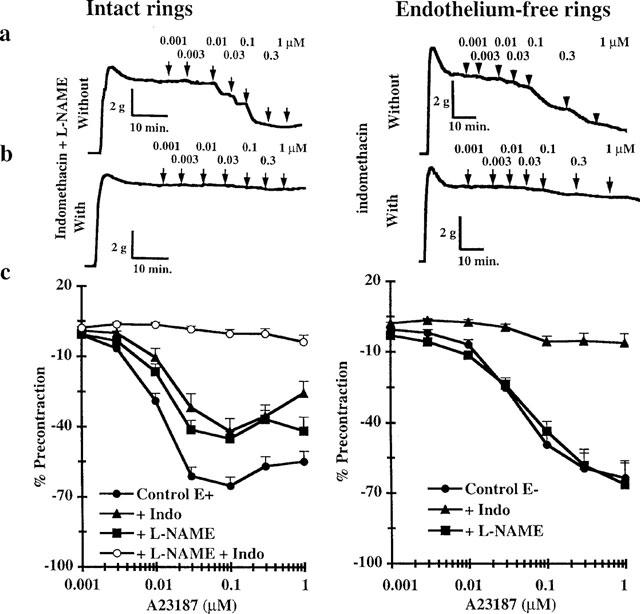

Intact rings of saphenous vein relaxed in response to A23187. Pretreatment with L-NAME (100μM) or indomethacin (10μM) reduced this response by 50% whereas concomitant pretreatment totally suppressed it. After endothelium removal, the remaining relaxing response to A23187 was prevented by indomethacin but not affected by L-NAME.

We conclude that stimulation of the cyclo-oxygenase pathway by arachidonic acid induced endothelium-dependent, PGE2/EP4 mediated relaxation of the rabbit saphenous vein. This process might participate in the A23187-induced relaxation of the saphenous vein and account for a relaxing component in the response of the vena cava to arachidonic acid. It was not observed in thoracic aorta because of the lack of a vasodilatory receptor and/or the poorer ability of this tissue than veins to produce PGE2.

Keywords: Saphenous vein, vena cava, arachidonic acid, A23187, relaxation

Introduction

In response to acetylcholine, ATP, thrombin or A23187, vascular endothelium produces nitric oxide (NO) and vasoactive metabolites of arachidonic acid as a result of activation of the cyclo-oxygenase pathway (DeMey et al., 1982; DeMey & Vanhoutte, 1982; Singer & Peach, 1983a,1983b; Miller & Vanhoutte, 1985; Vanhoutte & Miller, 1985; Lüscher et al., 1988; Rubanyi & Vanhoutte, 1988; Yamasaki & Toda, 1991; Yang et al., 1991; Cosentino et al., 1993; Garcia-Villalon et al., 1993). Although cultured arterial and venous endothelial cells synthesize similar amounts of NO and prostaglandins (D'Orléans-Juste et al., 1991; Upchurch et al., 1989), endothelial control of the vasculature appears to be different in veins and arteries isolated from the same species (DeMey et al., 1982; DeMey & Vanhoutte, 1982; Seidel & LaRochelle, 1987; Lüscher et al., 1988; Rubanyi and Vanhoutte, 1988; Yang et al., 1991; Garcia-Villalon et al., 1993; Sellke & Daï, 1993). Using isolated dog vessels, DeMey & Vanhoutte (1982) were the first to report that Ca2+-dependent stimulation of the endothelium produced sustained relaxation of precontracted arteries whereas in the corresponding veins it produced only weak and transient relaxations which were counteracted by contractions when the endothelium was maximally stimulated. Such differences in endothelium-dependent regulation between arteries and veins have subsequently been confirmed in vessels from other species including man (Lüscher et al., 1988; Yang et al., 1991). Presumably, venous and arterial endothelia release different relaxing and constricting mediators and/or the underlying smooth muscles have different reactivities to these mediators. If the first of these two possibilities is true, the weaker endothelium-dependent relaxation in isolated veins than arteries may be due to low NO synthetic activity and not to a weak venous response to NO (Miller & Vanhoutte, 1985; Seidel & LaRochelle, 1987; Vallance et al., 1989).

The mechanism of the differential control of venous and arterial tones by the cyclo-oxygenase pathway of the vascular wall remains unclear. Maximal stimulation of the venous endothelium by acetylcholine, ATP, thrombin or A23187 produces cyclo-oxygenase-dependent contractions which counteract a weak NO-mediated relaxation (Cosentino et al., 1993; Garcia-Villalon et al., 1993; Sellke & Daï, 1993). Such cyclo-oxygenase-dependent contractions result from activation of the TP receptors in the smooth muscle (Miller & Vanhoutte, 1985; Lüscher et al., 1988; Yang et al., 1991). In vitro, direct stimulation of cyclo-oxygenase activity by exogenous arachidonic acid results in qualitatively and quantitatively different effect in arteries and veins: canine veins exhibit endothelium-dependent, TP receptor-mediated contractions whereas the corresponding arteries exhibit endothelium-dependent relaxations which are blocked by cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors (DeMey & Vanhoutte, 1982; Miller & Vanhoutte, 1985; Vanhoutte & Miller, 1985). Neither the inhibitory prostaglandin or the receptor involved in the vasorelaxant effects of arachidonic acid on canine arteries have been identified.

A highly sensitive, vasodilatory PGE2 receptor subtype, called EP4, has been described in isolated veins from pig (Louttit et al., 1992a,1992b; Coleman et al., 1994) and rabbit (Lydford & McKechnie, 1994a; Milne et al., 1995; Lydford et al., 1996a) but has never been reported in any arterial tissue. In these species, the differential responses of veins and arteries to stimulation of the cyclo-oxygenase pathway have never been explored. We therefore tested whether the venous wall produces enough PGE2 to stimulate EP4 receptors and in turn provoke venous relaxation. Thus, we studied the contractile responses of rings of rabbit saphenous vein and vena cava and rings of thoracic aorta from the same animal to exogenous arachidonic acid. The productions of PGE2, 6keto-PGF1α and TXB2 by isolated vascular rings were measured. We conclude that in response to stimulation of the cyclo-oxygenase pathway, isolated rabbit veins produced more PGE2 than did aorta. In saphenous vein, this provoked an EP4-mediated response which accounted for arachidonic acid induced relaxation and might contribute to the endothelium-dependent relaxant response to the calcium ionophore, A23187. This mechanism might participate in the arachidonic acid-mediated relaxation in the vena cava, but was not observed in thoracic aorta presumably because of the lack of a vasodilatory receptor and/or the poor ability of this tissue to produce prostaglandins.

Methods

Vessel isolation

Male New Zealand rabbits weighing 3 kg were treated with heparin (200 IUkg-1) and sacrified by intravenous injection of sodium pentobarbital (50 mgkg-1). External saphenous vein, vena cava and/or throracic aorta were rapidly dissected and rinsed in bubbled (95% O2-5% CO2) Krebs-Henseileit solution (KH-solution) containing (mM): NaCl 118.4, KCl 4.7, MgSO4 1.2, CaCl2 1.3, KH2PO4 1.2, NaHCO3 25 and 11.7 glucose, pH 7.4. Fat was removed and vessels were cut transversely to give eight (saphenous vein), five (thoracic aorta) or three (vena cava) rings approximately 4 mm long. When required, the endothelium was mechanically scraped off by gentle rubbing of the luminal surface with curved forceps. The rings were then mounted on parallel wires, one of which was fixed and the other attached to a force transducer (EMKA, France) allowing tension changes to be recorded isometrically. The rings were bathed in 20 ml KH solution maintained at 37°C and continuously gassed with 95% O2-5% CO2.

In vitro measurement of contraction

Rings were stretched at resting tensions of 2 g (thoracic aorta) and 1.6 g (saphenous vein or vena cava). These stretch tensions were optimal according to previous determinations of length-tension relationships. Tissues were equilibrated for 45 min before challenge with 100 mM KCl KH solution. Once a plateau was attained, endothelial function was checked by addition of acetylcholine (from 0.1–10 μM) to the bath. Tissues were then washed with 5 mM KCl KH solution to recover their resting tension and tested twice with 100 mM KCl KH-solution and subsequent addition of acetylcholine. The amplitude of contraction after this second 100 mM KCl challenge was the maximal tension which could be developed by the rings: higher KCl concentrations did not further increase the tension. The mean KCl tension was 7.8±0.1 g for saphenous vein (n=348), 1.2±0.1 g for vena cava (n=107) and 9.6±0.2 g for thoracic aorta (n=170). In intact rings, maximal relaxations obtained in response to acetylcholine were −44.7±1% (n=237) of the maximal contraction of saphenous vein, −60±3% (n=64) of vena cava and −32±1 % (n=93) of thoracic aorta. No significant acetylcholine-induced relaxation was observed when the endothelium had previously been scraped off (−5.3±0.3%, n=110 for saphenous vein; −5±1 %, n=30 for vena cava; −2.0±0.4%, n=51 for thoracic aorta). After these functional tests, rings were maintained at rest for 90 min in 5 mM KCl KH-solution. To detect both contraction and relaxation in response to the various agents tested, rings were treated with KH solution containing 40 mM KCl for saphenous vein, 30 mM KCl for thoracic aorta and 20 mM KCl for vena cava. At these KCl concentrations, the rings were approximately half activated (from 30–70% of the maximal contraction) whether or not the endothelium was present. Once the precontraction plateaued, increasing doses of arachidonic acid, PGE2, PGI2 or A23187 were added to the bath. In some experiments, a TP receptor antagonist (GR32191B or SQ29548 at 3 μM), a cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor (indomethacin 10 μM), an EP4 receptor antagonist (AH23848B) or an appropriate vehicle was added 30 min before precontraction and remained until the end of the experiment. Although, the potency of TP receptor antagonists for rabbit tissues is lower than for human or rat tissues (Lumley et al., 1989; Tahraoui et al., 1990; Tymkewycz et al., 1991; Foster et al., 1992), GR32191B and SQ29548 were used at concentrations at least 30 fold higher than their previously reported pA2 values against rabbit TP-receptors (Lumley et al., 1989; Tahraoui et al., 1990; Foster et al., 1992; Lydford et al., 1996a). Because of the tachyphylaxis of the responses to arachidonic acid (DeMey et al., 1982) and PGE2 (data not shown), each vascular ring was used for only one dose-response analysis. The contracting and relaxing effects are expressed as the positive and negative mean±s.e.mean respectively of the percentage of the precontraction.

Eicosanoid production by vascular rings

Rings of rabbit saphenous vein, vena cava and thoracic aorta dissected as described above were immediately rinsed in Hank's saline solution (HBSS, Gibco-BRL) and cut tranversely into 4 mm long segments. The endothelium was mechanically removed from some segments by gentle rubbing of the luminal surface with curved forceps as for functional experiments. Because tissue dissection and preparation might acutely trigger the arachidonic acid cascade, the rings were allowed to recover for 90 min in fresh HBSS, before experiments. After the recovery period, rings were equilibrated for 30 min under constant shaking in 500 μl physiological buffer containing (in mM): HEPES 20, NaCl 120, KCl 4.7, MgSO4 1.2, CaCl2 1.25, 10 glucose, KH2PO4 1.2, pH 7.4 with or without 10 μM indomethacin. At t=0, they were transferred into 500 μl of the same buffer with or without 1 μM arachidonic acid. Thirty minutes later, they were removed and the medium was frozen at −80°C. Each ring was superficially dried and weighed. Amounts of PGE2, 6keto-PGF1α and TXB2 in the medium were determined within a week using commercially available enzymeimmunoassay kits (Amersham). According to the manufacturer, crossreactivities of the kits with related compounds were less than 1%. Results are expressed as means±s.e.mean pg of eicosanoid per mg wet weight.

Drugs and statistics

Arachidonic acid, PGE2, PGI2 and SQ29548 were purchased from Spibio (Massy, France). All other drugs were from Sigma Chemical (St Quentin Fallavier, France). Solutions were freshly prepared before use. For stock solutions, arachidonic acid was dissolved in ethanol, PGE2 in water and PGI2 in Tris buffer (pH 9). A23187 was dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO). GR32191B and SQ29548 were prepared at 15 mM in DMSO and ethanol respectively. AH23848B and indomethacin were dissolved at 10 mM in 0.5 M NaHCO3. NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) was dissolved at 0.4 M in water. Subsequent dilutions were made in physiological saline solution. Results are expressed as means±s.e.mean. Differences are considered significant when P<0.05 using the non-parametric transformation of the unpaired t-test: standard Mann-Whitney U-test.

Results

Responses to arachidonic acid and effects of TP receptor antagonists

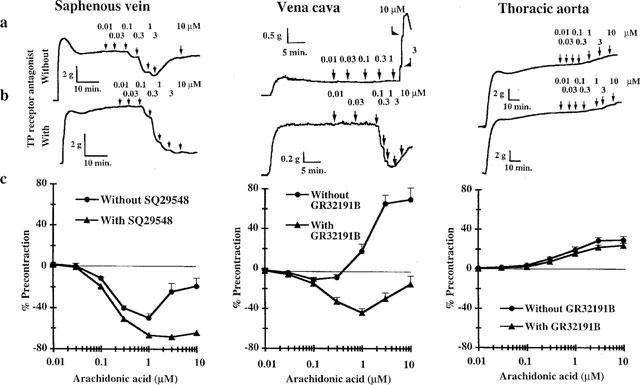

Arachidonic acid (0.001–1 μM) provoked potent relaxation of intact rings of the rabbit saphenous vein (−50±4% at 1 μM, n=4) whereas those of vena cava and thoracic aorta were insensitive to this range of concentrations (Figure 1a). Higher concentrations of arachidonic acid induced contraction of saphenous vein (−18.6±7.8% at 10 μM, n=4), vena cava (+69.6±13.6% at 10 μM, n=7) and thoracic aorta (+29.3±3.6% at 10 μM, n=15). This contractile phenomenon counteracted but did not totally reverse the potent relaxing effect of arachidonic acid on saphenous vein (−18.6±7.8% at 10 μM vs −50±4% at 1 mM; P<0.001). In rings of vena cava the onset of contraction was rapid and plateaued 1–2 min after addition of the following dose. Pretreatment with a TP receptor antagonist (3 μM GR32191B or 3 μM SQ29548, Figure 1b) abolished or reduced the contraction in response to high doses of arachidonic acid in saphenous vein and vena cava respectively but failed to prevent arachidonic acid-induced contraction in aorta. The blockade of TP receptors potentiated the arachidonic acid-induced relaxation observed in saphenous vein but also revealed a dose-dependent inhibitory component in the response of rabbit vena cava (−44.1±4.2% at 1 μM, n=24, P<0.001). Nevertheless, even in the presence of 3 μM GR32191B, a contraction in vena cava still counteracted the relaxing effect at doses higher than 1 μM (−15.4±8.2% at 10 μM).

Figure 1.

Effects of cumulative doses of arachidonic acid on rings of rabbit saphenous vein, vena cava and thoracic aorta submaximally contracted by external application of KCl. Time courses of representative experiments without (a) and with (b) 3 mM TP receptor antagonist (SQ29548 or GR32191B) pretreatment. (c) Summarized results obtained with untreated rings (n=4, 7, 15) and rings pretreated with the TP receptor antagonist (n=40, 21, 25 for saphenous vein, vena cava and thoracic aorta respectively). Results are expressed as means±s.e.mean of percentage of KCl precontraction.

Effects of cyclo-oxygenase inhibition and removal of the endothelium

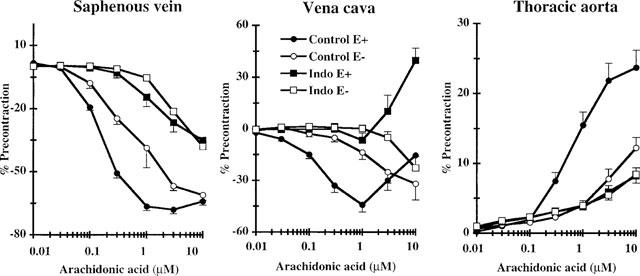

We investigated whether the TP receptor-independent effects of arachidonic acid were due to stimulation of the endothelial cyclo-oxygenase pathway. Intact rings and endothelium-free rings were pretreated with a TP receptor antagonist and 10 μM indomethacin (an inhibitor of cyclo-oxygenase activity). Prior blockade of the cyclo-oxygenase pathway provoked a 10 fold rightward shift in the dose-response curve in intact saphenous vein to arachidonic acid and totally suppressed the relaxing response of intact vena cava (Figure 2). In vena cava, indomethacin pretreatment potentiated the TP receptor-independent contraction (+39.7±7.1% at 10 μM, n=21). In thoracic aorta, the cyclo-oxygenase blockade significantly reduced the TP receptor-independent response to arachidonic acid (+8.2±1.1% at 10 μM, n=9).

Figure 2.

Effects of endothelium removal and/or cyclo-oxygenase inhibition on the effects of arachidonic acid on rabbit saphenous vein, vena cava and thoracic aorta preincubated with 3 mM TP receptor antagonist (SQ29548 or GR32191B). Intact rings (E+) and endothelium-free rings (E−) were incubated without (Control) or with 10 mM indomethacin (Indo). Results are expressed as means±s.e.mean of 8–40 rings depending on the experimental conditions for saphenous vein, 7–21 rings for vena cava and 9–25 rings for thoracic aorta.

Elimination of the endothelium of the vessels totally suppressed acetylcholine-induced relaxation during preliminary functional tests but did not suppress the relaxation responses in either saphenous vein or vena cava. Endothelium removal caused a 3–10 fold rightward shift in the relaxant dose-response curves for these tissues to arachidonic acid. The remaining vasorelaxant response of endothelium-free saphenous vein and vena cava was inhibited by indomethacin pretreatment. Interestingly, the TP receptor-independent contraction observed in intact vena cava at high dose of arachidonic acid was eliminated by endothelium removal. The contraction observed in intact rings of thoracic aorta was significantly reduced by endothelium removal and indomethacin pretreatment did not further reduce the response.

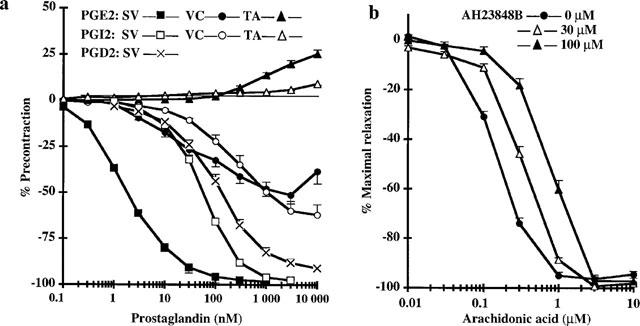

Response to vasorelaxant prostaglandins and effect of AH23848B on the response of saphenous vein to arachidonic acid

Concentration-response curves of rabbit saphenous vein to exogenous PGE2, PGI2 and PGD2 were obtained with KCl precontracted rings (Figure 3a). As previously described (Lydford et al., 1996a), this tissue appeared 50 and 100 fold more sensitive to PGE2 than to PGI2 and PGD2 respectively (EC50=1.6±0.1 nM, Emax=−97.5±0.8%, nH=1.00 for PGE2; EC50= 55.8±2.1 nM, Emax=−99.1±0.9%, nH=1.20 for PGI2; EC50=112±5 nM, Emax=−92.5±0.9%, nH=0.82 for PGD2). This suggested a relaxation primarily mediated by activation of vasodilatory EP2 and/or EP4 receptors in the smooth muscle. As in saphenous vein, PGE2 was more potent than PGI2 for relaxing vena cava. Nevertheless, the response to PGE2 was weaker and certainly more complex than that observed in saphenous vein spanning more than 3 log units (EC50= 29.6±5.8 nM, Emax=−63.6±2.2%, n=9, nH=0.55). Unlike venous tissues, rabbit aorta did not relax but exhibited moderate contractions in response to PGE2 and PGI2 (+9.9±3.2%, n=14, for PGE2; +12.7±1.2% for PGI2 at 10 μM).

Figure 3.

Effects of PGE2 and EP4 antagonist receptor, AH23848B, on the arachidonic acid response of saphenous vein. (a) Effects of cumulative doses of PGE2, PGI2 and PGD2 on precontracted saphenous vein (SV, n=12–15) and cumulative doses of PGE2 and PGI2 on precontracted vena cava (VC, n=7–9) and thoracic aorta (TA, n=8–14). Experiments were performed on rings without endothelium in the presence of 3 μM TP receptor antagonist. Results are expressed as the means±s.e.mean. (b) Effects of pretreatment with 30 μM and 100 μM EP4 antagonist receptor, AH23848B, or vehicle on the effects of cumulative doses of arachidonic acid on precontracted saphenous vein. Experiments were performed on rings with endothelium in the presence of 3 μM TP receptor antagonist. Results are expressed as means±s.e.mean of percentage of maximal relaxation, n=8–40 depending on the experimental conditions.

Because the potent vasodilatory response of rabbit saphenous vein to PGE2 can be weakly antagonized by AH23848B, an antagonist of the PGE2 receptor subtype EP4 (pA2=4.96, Lydford et al., 1996a), we tested for the involvement of EP4-mediated relaxation in the vasodilatory response of the saphenous vein to arachidonic acid (Figure 3b). Saphenous vein was treated with AH23848B in the presence of 3 mM SQ29548 to potentiate the vasodilatory response and to mask the TP receptor-mediated effects of AH23848B. At doses known to prevent PGE2 interaction with EP4 receptor (pA2=4.9–5.4; Coleman et al., 1994; Lydford et al., 1996a), pretreatment with 30 and 100 μM AH23848B produced dose-dependent rightward shifts in the response to exogenous arachidonic acid.

Prostaglandin and thromboxane productions

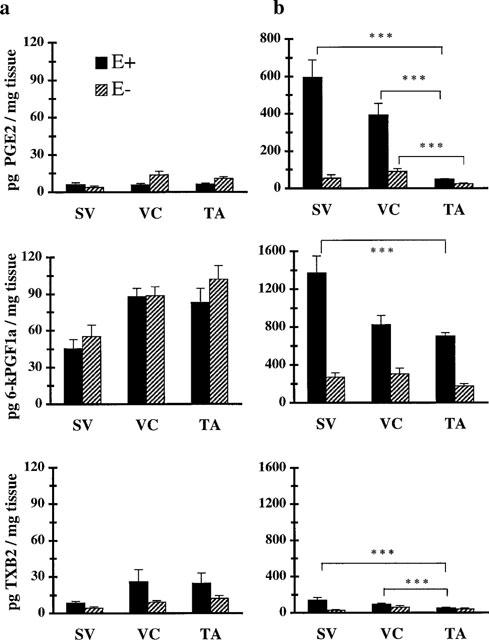

There results suggested that direct stimulation of the venous wall cyclo-oxygenase by exogenous arachidonic acid causes production of eicosanoids which interact with one or several inhibitory or constricting receptors. In a separate set of experiments, we compared the productions of PGE2 and of the stable analogues of PGI2 and TXA2, 6keto-PGF1α and TXB2 by intact and endothelium-free rings, in the presence or absence of 1 μM arachidonic acid (Figure 4). Under all experimental conditions, eicosanoid production by venous and arterial rings was totally inhibited by previous pretreatment with 10 μM indomethacin (data not shown). The ‘basal' productions of PGE2, 6keto-PGF1α and TXB2 by intact rings of rabbit saphenous vein, vena cava and thoracic aorta were similar. In the presence of 1 μM arachidonic acid, intact rings of saphenous vein and vena cava produced 1.5–2 fold more cyclo-oxygenase derivatives than did aorta. This was mainly due to an approximately 10 fold larger production of PGE2. The amount of 6keto-PGF1α produced was similar and that of TXB2 1.5–2 fold higher. Nevertheless, even for venous tissues, 6keto-PGFα was the major metabolite produced by intact vascular rings. Removal of the endothelium did not significantly modify unstimulated production of PGE2, 6keto-PGF1α or TXB2 by venous or arterial rings. When stimulated by the fatty acid, the total eicosanoid production by the endothelium-free rings was only 25–30% of that by intact rings of the same origin. Without endothelium, stimulated venous rings still produced 2–3 fold more PGE2 than rings from aorta although 6keto-PGF1α remained the most abundant prostaglandin synthesized by both venous and arterial rings.

Figure 4.

Measurements of PGE2, 6-ketoPGF1α and TXB2 production by rings isolated from saphenous vein (SV), vena cava (VC) and thoracic aorta (TA) in basal conditions (a) and stimulated by the addition of 1 μM arachidonic acid (b). Open columns represent production by intact rings (E+) and hatched columns illustrate production by endothelium-free rings (E−). Results are expressed as means±s.e.mean of percentage of 8–35 rings depending on the experimental conditions. ***, P<0.001.

Effect of indirect stimulation of cyclo-oxygenase by A23187

Because direct stimulation of the cyclo-oxygenase pathway by arachidonic acid relaxed precontracted rings of rabbit saphenous vein even in the absence of TP receptor antagonist, cyclo-oxygenase-dependent relaxation might occur in response to Ca2+-dependent release of endogenous fatty acid in this tissue. From 1–100 nM, the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 induced a dose-dependent relaxation of intact rings of saphenous vein. At higher doses, this relaxation was counteracted by a contraction. This late phenomenon persisted in the presence of a TP receptor antagonist (data not shown). Pretreatment with either the NO-synthase inhibitor, L-NAME (100 μM), or the cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor, indomethacin (10 μM), reduced the relaxant response to A23187 by 50% (Figure 5). Concomitant pretreatment with L-NAME and indomethacin totally suppressed both the relaxing and contracting responses to A23187. In endothelium-free rings of saphenous vein, A23187 induced desensitized relaxation relative to that observed on intact rings (EC50=41.7±1.5 nM, n=32 vs EC50=10.7±1.5 nM, n=43). This relaxing response was prevented by indomethacin but not L-NAME pretreatment.

Figure 5.

Effects of cumulative doses of A23187 on KCl precontracted intact or endothelium-free rings of saphenous vein rings. Time courses of representative experiments performed without (a) and with concomitant pretreatment with NO synthase inhibitor (L-NAME, 100 μM) and cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor (indomethacin, 10 μM) (b, left) and only with cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor (indomethacin, 10 μM) (b, right). (c) Results obtained with untreated rings (n=32–43), and rings pretreated with indomethacin (n=8–16) and/or L-NAME (n=11–25).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the contraction of both a distal (saphenous vein) and a proximal (vena cava) rabbit vein can be regulated by the cyclo-oxygenase activity of the endothelium. This contrasts with the weak responses observed in aorta from the same animal. As described in venous tissues from dog and human (DeMey & Vanhoutte, 1982; Yang et al., 1991), stimulation of the cyclo-oxygenase activity by arachidonic acid at concentrations higher than 1 μM induced TP receptor-mediated contraction of both rabbit saphenous vein and vena cava. This TP receptor-mediated effect counteracted a potent arachidonic acid-induced vasodilatation in the saphenous vein and totally masked a vasodilatory component in the vena cava response.

The arachidonic acid-induced relaxation of both saphenous vein and vena cava, in the presence of TP receptor antagonist, was inhibited by indomethacin pretreatment and by endothelium removal. This suggests that when the cyclo-oxygenase pathway was stimulated by arachidonic acid, vasodilatory prostaglandins were mostly produced by the venous endothelium. Accordingly, in the presence of 1 μM arachidonic acid, intact but not endothelium-free rings of saphenous vein and vena cava produced large amounts of PGE2 and PGI2 (6keto-PGF1α), both prostaglandins with potent vasodilatory effects in these tissues. In agreement with Lydford's results (1996a), the apparent reactivity of saphenous vein to exogenous PGE2 appeared 50 fold greater than those to PGI2 and PGD2 suggesting that the receptors involved in the relaxant response to arachidonic acid or A23187 could be EP-receptors. Relaxation of the rabbit saphenous vein that in response to exogenous prostaglandins is primarily mediated by EP4 receptor subtypes although the presence of EP2 and DP receptors cannot be excluded (Lydford et al., 1996a). In our study, the rightward shifts in the dose-response curve to arachidonic acid provoked by AH23848B were consistent with an EP4-mediated effect of arachidonic acid. Indeed, since the original paper of Coleman et al. (1994) describing the pharmacology of an EP4-mediated response in piglet saphenous vein, AH23848B has been widely used to discriminate EP4 mediated-relaxant responses from EP2, IP or DP receptor-mediated relaxation in isolated smooth muscle preparations (Louttit et al., 1992b; Lydford & McKechnie., 1994b; Milne et al., 1995; Lydford et al., 1996a,1996b). Experiments with rat recombinant prostaglandin receptors confirm the selective antagonism of AH23848B at EP4 receptors relative to EP2 receptors (Boie et al., 1997). AH23848B exhibits antagonist properties at almost all human recombinant receptors except the IP receptor. Notably, it similarly antagonizes EP2-, DP- as well as EP4-mediated responses in transfected cells. Thus, whereas we could definitely exclude activation of IP receptor, EP2 and DP receptor activation may participate in the arachidonic acid-induced relaxation observed in rabbit saphenous vein. Nevertheless, it has been shown that AH23848B fails to antagonize the relaxation induced in rabbit saphenous vein by the EP2 selective agonists AH13205 and butaprost (Lydford et al., 1996a) ruling out the putative influence of EP2 receptor activation in the arachidonic acid-induced relaxation that we observed. Furthermore, the relaxant response of rabbit saphenous vein to PGD2 is effectively antagonized by AH23848B (Lydford et al., 1996b), but PGD2 is known to activate recombinant human EP4 receptors at concentrations consistent with the apparent reactivity of the saphenous vein that we report (Wright et al., 1998). Thus, the antagonism of AH23848B on the arachidonic acid concentration response curve was probably due to its interaction with EP4 receptors in the smooth muscle.

Even in the presence of 10 μM indomethacin, SQ29548-treated saphenous vein relaxed in response to concentrations of arachidonic acid higher than 1 μM. This could not be due to incomplete blockade of cyclo-oxygenase activity since in the presence of 1 μM arachidonic acid, prostaglandin production by rings of saphenous vein was totally inhibited by 10 μM indomethacin. Numerous arachidonic acid derivatives which are not prostaglandins promote relaxation of vascular preparations. Notably, cytochrome P-450 derivatives of arachidonic acid might account for endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors (Rubanyi & Vanhoutte, 1987; Komori & Vanhoutte, 1990; Bennett et al., 1992; Hecker et al., 1994; Dong et al., 1997).

The role of cyclo-oxygenase in the relaxation of the rabbit saphenous vein provoked by the calcium ionophore A23187 was explored. A23187 induced a NO-mediated relaxation and a cyclo-oxygenase-dependent vasodilatory process in intact rings. Interestingly, whereas the NO-mediated component of the response was totally suppressed by endothelium removal, cyclo-oxygenase-dependent relaxation was observed in endothelium-free rings. One possible explanation is that both endothelial and smooth muscle cyclo-oxygenase activities were stimulated by A23187 and produced vasodilatory prostaglandin(s), possibly PGE2. Alternatively, contaminating endothelial cells or endothelium of the vasa vasorum may have produced vasodilatory prostaglandins but failed to produce enough NO to provoke stimulation of the smooth muscle guanylate cyclase. We favour the former hypothesis because the endothelium removal procedure totally suppressed the acetylcholine-induced relaxation observed in intact rings. Furthermore, endothelium removal did not suppress arachidonic acid-induced relaxation in the saphenous vein but provoked a rightward shift of only one order of magnitude in the dose-response curve, suggesting a role for a non-endothelial cyclo-oxygenase activity.

The involvement of PGE2 in the vasodilatory component of the response of vena cava to arachidonic acid is certainly more debatable than in saphenous vein: (i) In the presence of arachidonic acid, vena cava and saphenous vein rings produced comparable amounts of PGE2 and PGI2 but PGE2 was at least 10 fold less potent in vena cava than in saphenous vein; (ii) In the presence of stimulating concentration of arachidonic acid, rings of vena cava produced twice as much PGI2 as PGE2, (iii) Vena cava appeared 10 fold more sensitive to PGE2 than to native PGI2 but this difference could result from the short half-life of PGI2 in aqueous solution. Although PGI2 was conserved as a stock solution in ice-cooled basic buffer (pH 9) to ensure stability until the experiments (Johnson, 1976), we could not avoid PGI2 degradation once it was added to the bath solution. Indeed, the half life in aqueous solution (Dusting et al., 1977) and the time required to reach maximal relaxation in vena cava were comparable (2–4 min). Thus, the true PGI2 concentration when the plateau was reached could be 2–4 fold lower than that initially added. The dose-response curve of vena cava to PGE2 spanned a wide range of concentrations (3–4 log units) suggesting activation of more than one vasodilatory receptor in this preparation. Alternatively, a contractile component in the response to PGE2 via activation of excitatory prostanoid receptors distinct from TP receptor (EP1, EP3 or FP) could distort the shape of the curve and account for incomplete relaxation of the vena cava. Further studies are certainly required to characterize the vasodilatory prostanoid receptors in the rabbit vena cava but note that the highly sensitive PGE2 receptor subtype, EP4, has been described in several rabbit veins (Milne et al., 1995; Lydford et al., 1996a), but not in any artery. Therefore, we postulate that arachidonic acid-induced relaxation in the rabbit vena cava might be due to production of both PGE2 and PGI2 by the endothelium and subsequent activation of vasodilatory EP2, EP4 and/or IP receptors on the smooth muscle.

In the absence of TP receptor antagonist, arachidonic acid concentrations higher than 1 μM induced contraction which either reduced (saphenous vein) or masked (vena cava), cyclo-oxygenase-dependent relaxation in veins (see above). Studies with isolated canine and human veins consistently report such a TP receptor-mediated constriction in response to arachidonic acid or to endothelium stimulation by A23187, acetylcholine and thrombin (DeMey & Vanhoutte, 1982; Miller & Vanhoutte, 1985; Lüscher et al., 1988; Yang et al., 1991). These excitatory responses may result from the endothelium producing eicosanoids other than TXA2 (mainly the endoperoxide PGH2) which activate TP receptors (Miller & Vanhoutte, 1985; Van Dam et al., 1986; Pagano et al., 1991; Williams et al., 1994). In our study, although stimulated venous rings produced large amounts of PGE2 and PGI2, TXA2 production accounted for only 10% of the total eicosanoid production. Thus, in situ, the local concentration of eicosanoids other than TXA2 in the vicinity of the smooth muscle cells might be much higher than that of TXA2, accounting for the TP receptor-mediated contraction observed in saphenous vein and vena cava. Such a TP receptor-mediated contraction in response to arachidonic acid has been previously reported (Pagano et al., 1991) in rabbit aorta. In our experiments, we were unable to prevent cyclo-oxygenase-dependent contraction by a TP-receptor blocking agent. Our results suppose that stimulation of the rabbit aorta cyclo-oxygenase pathway induced synthesis of prostanoids by the endothelium which might activate constricting receptor(s) (Singer & Peach, 1983a) such as FP, EP1 or EP3 receptors.

Arachidonic acid concentrations higher than 1 μM lead to an endothelium-dependent contraction in the vena cava counteracting the vasodilatory component observed after pretreatment with a TP-receptor antagonist. This contraction was potentiated by indomethacin pretreatment. High concentrations of arachidonic acid in this tissue might result in the production of constricting eicosanoids other than prostaglandins and thromboxane.

One of our main findings is that, in the presence of arachidonic acid, rings of saphenous vein and vena cava produced 8–10 fold more PGE2 than rings of thoracic aorta whereas the synthesis of PGI2 by the venous and arterial rings were similar. Because PGI2 has both vasorelaxant effects in several (but not all, Omini et al., 1977) vascular preparations (Williams et al., 1994) and is an extremely potent inhibitor of platelet aggregation, numerous authors have compared the synthesis of PGI2 by vascular rings or by cultured endothelial cells from veins and arteries. Published results are conflicting, showing either lower (Chaikhouni et al., 1986; Fann et al., 1989; Nadasy et al., 1992), similar (Carter et al., 1984; Hanley & Bevan, 1985; D'Orleans-Juste et al., 1991) or higher (Upchurch et al., 1989) PGI2 synthesis in veins than in arteries. Skidgel & Prinz (1978) observed that homogenates of rat arteries generated substantial amounts of PGI2 but venous homogenates from the same animal did not, producing PGE2 instead. Our results confirm this observation in the rabbit and provide evidence for a major role for PGE2 in the cyclo-oxygenase-dependent control of vein contraction. As in arterial rings, the synthesis of prostaglandins by the venous tissues mainly resulted from the cyclo-oxygenase activity of the endothelium. Indeed, endothelium removal reduced the venous production of PGE2 by 75–90%. Endothelium-free venous rings produced more (2–4 fold) PGE2 than those from aorta suggesting that the difference between veins and aorta might be due to differences in non-endothelial cyclo-oxygenase and/or PGE2 isomerase activities. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the remaining production of prostaglandins after rubbing of the luminal surface of the vessels (to remove the endothelium) resulted from incomplete endothelial elimination. Interestingly, the absence of the arachidonic acid-induced relaxing response in the aorta was due to the absence of vasodilatory eicosanoid receptors rather than to failure of the arterial wall to produce prostaglandins. Indeed, in the presence of 1 μM arachidonic acid, intact rings of rabbit aorta produced significant amounts of PGI2 and PGE2.

Our results highlight the role of PGE2 in the control of rabbit vein relaxation by the cyclo-oxygenase pathway whereas aorta from the same animal appeared almost insensitive to cyclo-oxygenase stimulation. This venospecific cyclo-oxygenase-dependent relaxation in the rabbit may result from both the expression of a highly sensitive PGE2 receptor subtype, EP4, and also the greater capacity of the venous than arterial endothelium to produce PGE2.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the ‘Association Nationale de la Recherche Technique' (Convention no. 42294). We thank S. Desquand, G. Gimeno, V. Latournerie and F. Mardon for helpful discussion.

References

- BENNETT B.M., MCDONALD B.J., NIGAM R., LONG P.G., SIMON W.C. Inhibition of nitrovasodilator- and acetycholine-induced relaxation and cyclic GMP accumulation by the cytochrome P-450 substrate, 7-ethoxyresorufin. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1992;70:1297–1303. doi: 10.1139/y92-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOIE Y., STOCCO R., SAWYER N., SLIPETZ D.M., UNGRIN M.D., NEUSCHÄFER-RUBE F., PÜSCHEL G.P., METTERS K.M., ABRAMOVITZ M. Molecular cloning and characterization of the four rat prostaglandin E2 prostanoid receptor subtypes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;340:227–241. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARTER A.J., BEVAN J.A., HANLEY S.P., MORGAN W.E., TURNER D.R. A comparison of human pulmonary arterial and venous prostacyclin and thromboxane synthesis–effect of a thromboxane synthase inhibitor. Thromb. Haemostas. 1984;51:257–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAIKHOUNI A., CRAWFORD F.A., KOCHEL P.J, , OLANOFF L.S., HALUSHKA P.V. Human internal mammary artery produces more prostacyclin than saphenous vein. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1986;92:88–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLEMAN R.A., GRIX S.P., HEAD S.A., LOUTTIT J.B., MALLETT A., SHELDRICK R.L.G. A novel inhibitory receptor in piglet saphenous vein. Prostaglandins. 1994;47:151–168. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(94)90084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COSENTINO F., SILL J.C., KATISUC Z.S. Role of superoxyde anions in the mediation of endothelium-dependent contractions. Hypertension. 1993;23:229–235. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEMEY J.G., CLAEYS M., VANHOUTTE P.M. Endothelium-dependent inhibitory effect of acetylcholine, adenosine triphosphate, thrombine and arachidonic acid in the canine femoral artery. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1982;222:166–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEMEY J.G., VANHOUTTE P.M. Heterogenous behavior of the canine arterial and venous wall: importance of the endothelium. Circ. Res. 1982;51:439–447. doi: 10.1161/01.res.51.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DONG H., WALDRON G.J., GALIPEAU D., COLE W.C., TRIGGLE C.R. NO/PGI2-independent vasorelaxation and the cytochrome P-450 pathway in rabbit carotid artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:695–701. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'ORLEANS-JUSTE P., MICHELL J.A., WOOD E.G., HECKER M., VANE J.R. Comparison of the release of vasoactive factors from venous and arterial bovine cultured endothelial cells. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1991;70:687–694. doi: 10.1139/y92-088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUSTING G.J., MONCADA S., VANE J.R. Prostacyclin (PGX) is the endogenous metabolite responsible for relaxation of coronary arteries induced by arachidonic acid. Prostaglandins. 1977;13:3–15. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(77)90037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FANN J.I., CAHILL P.D., MITCHELL R.S., MILLER D.C. Regional variability of prostacyclin biosynthesis. Artheriosclerosis. 1989;9:368–373. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.9.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOSTER M.R., HORNBY E.J., STRATTON L.E. Effect of GR32191 and other thromboxane receptor blocking drugs on human platelet deposition onto de-endothelialized arteries. Thromb. Res. 1992;65:769–784. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(92)90115-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCIA-VILLALON A.L., FERNANDEZ N., GARCIA J.L., MONGE L., GOMEZ B., DIEGUEZ G. Reactivity of the dog cavernous carotid artery: The role of the arterial and venous endothelium. Eur. J. Physiol. 1993;425:256–262. doi: 10.1007/BF00374175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON R.A. The chemical structure of prostaglandin H (prostacyclin) Prostaglandins. 1976;12:915–928. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(76)90126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANLEY S. P. &, BEVAN J. Inhibition by aspirin of human arterial and venous prostacyclin synthesis. Prostaglandins Leukotrienes and Medicine. 1985;20:141–149. doi: 10.1016/0262-1746(85)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HECKER M., BARA A.T., BAUERSACHS J., BUSSE R. Characterization of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor as a cytochrome P-450-derived arachidonic acid metabolite in mammals. J. Physiol. 1994;481:407–414. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOMORI K., VANHOUTTE P.M. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Blood Vessels. 1990;27:238–245. doi: 10.1159/000158815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOUTTIT J.B., HEAD S.A., COLEMAN R.A.Eicosanoid EP-receptors in pig saphenous vein 1992ap. 257In proceed. of 8th internat. conf. in prostaglandins and related compounds

- LOUTTIT J.B., HEAD S.A., COLEMAN R.A.AH23848B: A selective blocking drug at EP-receptors in pig saphenous vein 1992bp. 258In proceed. of 8th internat. conf. in prostaglandins and related compounds

- LÜSCHER T.F., DIEDERICH D., SIEBENMANN R., LEHMANN K., STULZ P., VON SEGESSER L., YANG Z., TURINA M., GRÄDEL E., WEBER E., BÜHLER F.R. Difference between endothelium-dependent relaxation in arterial and in venous coronary bypass grafts. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988;319:462–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198808253190802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUMLEY P., WHITE B.P., HUMPHREY P.P.A. GR32191, a highly potent and specific thromboxane A2 receptor blocking drug on platelets and vascular and airways smooth muscle in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1989;97:783–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb12017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LYDFORD S.J., MCKECHNIE K.C.W. Characterization of the prostaglandin receptors located on rabbit isolated saphenous vein. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994a;112:P523. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LYDFORD S.J., MCKECHNIE K.C.W. Characterization of the prostaglandin E2 sensitive (EP)-receptor in the rat isolated trachea. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994b;112:133–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LYDFORD S.J., MCKECHNIE K.C.W., DOUGALL I.G. Pharmacological studies on eicosanoid receptors in the rabbit isolated saphenous vein: A comparison with the rabbit isolated ear artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996a;117:13–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LYDFORD S.J., MCKECHNIE K.C.W., LEFF P. Interaction of BW A868C, a prostanoid DP-receptor antagonist, with two receptor subtypes in the rabbit isolated saphenous vein. Prostaglandins. 1996b;52:125–139. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(96)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER V.M., VANHOUTTE P.M. Endothelium-dependent contractions to arachidonic acid are mediated by products of cyclooxygenase. Am. J. Physiol. 1985;248:H432–H437. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.248.4.H432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILNE S.A., AMSTRONG R.A., WOODWARD D.F. Comparison of the EP receptor subtypes mediating relaxation of the rabbit jugular and pig saphenous vein. Prostaglandins. 1995;49:225–237. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(95)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NADASY G.L., SZEKACS B., JUHASZ I., MONOS E. Pharmacological modulation of prostacyclin and thromboxane production of rat and cat venous tissue slices. Prostaglandins. 1992;44:339–355. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(92)90007-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OMINI C., MONCADA S., VANE J.R. The effects of prostacyclin on tissues which detect prostaglandins. Prostaglandins. 1977;14:625–632. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(77)90189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAGANO P.J., LIN L., SESSA W.C., NASJLETTI A. Arachidonic acid elicits endothelium-dependent release from the rabbit aorta of a constrictor eicosanoid resembling prostaglandin endoperoxides. Circ. Res. 1991;69:396–405. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.2.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUBANYI G.M., VANHOUTTE P.M. Nature of endothelium-derived relaxing factor : are there two relaxing mediators. Circ. Res. 1987;61:II61–II67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUBANYI G.M., VANHOUTTE P.M. Heterogeneity of endothelium-dependent responses to acetylcholine in canine femoral arteries and veins. Blood Vessels. 1988;25:75–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEIDEL C.L., LAROCHELLE J. Venous and arterial endothelia: Different dilator abilities in dogs vessels. Circ. Res. 1987;60:626–630. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.4.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SELLKE F.W., DAI H.B. Responses of porcine epicardial venules to neurohumoral substances. Cardiovasc. Res. 1993;27:1326–1332. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.7.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINGER H.A., PEACH M.J. Endothelium-dependent relaxation of rabbit aorta. I. Relaxation stimulated by arachidonic acid. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1983a;226:790–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINGER H.A., PEACH M.J. Endothelium-dependent relaxation of rabbit aorta. II. Inhibition of relaxation stimulated by metacholine and A23187 with antagonists of arachidonic acid metabolism. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1983b;226:796–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SKIDGEL R.A., PRINTZ M.P. Prostacyclin production by rat blood vessels: Diminished prostacyclin formation in veins compared to arteries. Prostaglandins. 1978;16:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(78)90196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAHRAOUI L., FLOCH A., CAVERO I. Binding properties of the thromboxane antagonist tritium labelled SQ-29548 and U-46619-induced aggregation in human and rabbit platelets. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990;183:2250. [Google Scholar]

- TYMKEWYCZ P.M., JONES R.L., WILSON N.H., MARR C.G. Heterogeneity of thromboxane A2 (TP-) receptors: evidence from antagonist but not agonist potency measurements. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;102:607–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UPCHURCH G.R., BANES A.J., WAGNER W.H., RAMADAN F., LINK G.W., HENDERSON R.H., JOHNSON G. Differences in secretion of prostacyclin by venous and arterial endothelial cells grown in vitro in a static versus mechanically active environment. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1989;10:292–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALLANCE P., COLLIER J., MONCADA S. Nitric oxide synthetised from L-arginine mediates endothelium dependent dilatation in humans in vivo. Cardiovasc. Res. 1989;23:1053–1057. doi: 10.1093/cvr/23.12.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN DAM J., MADDOX Y.T., RAMWELL P.W., KOT P.A. Role of the vascular endothelium in the contractile response to prostacyclin in the isolated rat aorta. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1986;239:390–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANHOUTTE P.M., MILLER V.M. Heterogeneity of endothelium-dependent responses in mammalian blood vessels. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1985;7:S12–S23. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198500073-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WRIGHT D.H., METTERS K.M., ABRAMOVITZ M., FORD-HUTCHINSON A. Characterization of the recombinant human prostanoid DP receptor and identification of L-644,698, a novel selective DP agonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123:1317–1324. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS S.P, , DORN G.W., RAPOPORT R.M. PGI2 mediates contraction and relaxation of vascular smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;267:H796–H803. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.2.H796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMASAKI M., TODA N. Comparison of responses to angiotensin II of dog mesenteric arteries and veins. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991;201:223–229. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90349-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG Z., VON SEGESSER L., BAUER E., STULTZ P., TURINA M., LÜSCHER T. Different activation of the endothelial L-Arginine and cyclooxygenase pathway in the human internal mammary artery and saphenous vein. Circ. Res. 1991;68:52–60. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]