Abstract

The aims of this study were to determine: (1) whether vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) regulates cholinergic and ‘sensory-efferent' (tachykininergic) 35SO4 labelled mucus output in ferret trachea in vitro, using a VIP antibody, (2) the class of potassium (K+) channel involved in VIP-regulation of cholinergic neural secretion using glibenclamide (an ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channel inhibitor), iberiotoxin (a large conductance calcium activated K+ (BKca) channel blocker), and apamin (a small conductance Kca (SKca) channel blocker), and (3) the effect of VIP on cholinergic neurotransmission using [3H]-choline overflow as a marker for acetylcholine (ACh) release.

Exogenous VIP (1 and 10 μM) alone increased 35SO4 output by up to 53% above baseline, but suppressed (by up to 80% at 1 μM) cholinergic and tachykininergic neural secretion without altering secretion induced by ACh or substance P (1 μM each). Endogenous VIP accounted for the minor increase in non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic (NANC), non-tachykininergic neural secretion, which was compatible with the secretory response of exogenous VIP.

Iberiotoxin (3 μM), but not apamin (1 μM) or glibenclamide (0.1 μM), reversed the inhibition by VIP (10 nM) of cholinergic neural secretion.

Both endogenous VIP (by use of the VIP antibody; 1 : 500 dilution) and exogenous VIP (0.1 μM), the latter by 34%, inhibited ACh release from cholinergic nerve terminals and this suppression was completely reversed by iberiotoxin (0.1 μM).

We conclude that, in ferret trachea in vitro, endogenous VIP has dual activity whereby its small direct stimulatory action on mucus secretion is secondary to its marked regulation of cholinergic and tachykininergic neurogenic mucus secretion. Regulation is via inhibition of neurotransmitter release, consequent upon opening of BKCa channels. In the context of neurogenic mucus secretion, we propose that VIP joins NO as a neurotransmitter of i-NANC nerves in ferret trachea.

Keywords: Acetylcholine release, airways, cholinergic nerve, ferret trachea, iberiotoxin, mucus secretion, potassium channel, vasoactive intestinal peptide

Introduction

Airway neural pathways are classified currently as adrenergic, cholinergic and non-adrenergic non-cholinergic (NANC): they are anatomically interlinked and interact functionally. The excitatory and inhibitory neural mechanisms regulating airway smooth muscle function are relatively well defined (Barnes, 1996; Widdicombe, 1996). In contrast, for neurogenic airway mucus secretion, although excitatory pathways are comparatively well characterized (Rogers 1997), inhibitory pathways are poorly defined. In mammalian airways, the predominant neural control for mucus secretion is cholinergic with a minor adrenergic component. There is also a ‘sensory-efferent' neural pathway controlling mucus secretion. The nerves comprising the latter pathway are C-fibres sensitive to capsaicin and whose neurotransmitters are calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) and the tachykinins substance P (SP) and neurokinin A (NKA), collectively termed sensory neuropeptides (Ramnarine & Rogers, 1994). In ferret trachea in vitro, sensory-efferent pathways account for up to 40% of the total neurogenic secretory response, with the functional response (i.e. mucus secretion) mediated via tachykinin NK1 receptors on the secretory cells (Ramnarine et al., 1994). Nitric oxide (NO) and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) are neurotransmitters of inhibitory NANC (i-NANC) neural pathways regulating the magnitude of neurogenic bronchoconstriction, although their relative involvement varies with species (Lammers et al., 1992). We found that endogenous NO regulated the magnitude of neurogenic mucus secretion in ferret trachea in vitro (Ramnarine et al., 1996). The role of VIP as a regulator of neurogenic mucus secretion is unexplored.

Immunohistochemical studies localize VIP-containing airway nerves to intrinsic ganglia, smooth muscle, submucosal glands and blood vessels in human (Dey et al., 1981; Laitinen et al., 1985), dog and cat (Dey et al., 1988). VIP coexists with SP and galanin in cat airways (Dey & Zhu, 1994; Dey et al., 1988), nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and acetylcholine (ACh) in human airways (Fischer & Hoffman, 1996; Laitinen et al., 1985), neuropeptide Y (NPY) in guinea-pig trachea (Bowden & Gibbins, 1992), and with SP and NOS in ferret trachea (Dey et al., 1996). By autoradiography, VIP receptors are localized to submucosal glands, epithelium and smooth muscle in airways of pig (Lazarus et al., 1986), rat (Leroux et al., 1984) and human (Fischer et al., 1992). These anatomical studies imply that VIP has a role in modulating airway mucus secretion and may interact with other neurotransmitters.

In the present study, we explored the role of VIP on neural and non-neural control of mucus secretion in ferret trachea in vitro in Ussing chambers using 35SO4 as a mucus marker. Firstly, we determined the effect of VIP itself on non-neural mucus secretion. Secondly, we investigated the effect of VIP on cholinergic, tachykininergic, and non-NANC non-tachykininergic neural mucus secretion, using exogenous VIP, a selective VIP antibody (VIP-Ab) (Shimura et al., 1988), the peptidase α-chymotrypsin, or a putative VIP1 receptor antagonist [D-p-Cl-Phe6,Leu17]-VIP (Usdin et al., 1994) to investigate the role of endogenous VIP. Thirdly, we determined the class of potassium (K+) channel involved in VIP inhibition using the ATP sensitive K+ (KATP) channel inhibitor glibenclamide (Niki et al., 1989; Schmid-Antomarchi et al., 1990), the blocker of calcium activated K+ (KCa) channels of small conductance (SKca channels) apamin (Banks et al., 1979), and the large conductance Kca (BKca) channel blocker iberiotoxin (Garcia et al., 1991). Finally, to more directly confirm a neuromodulatory role for VIP on cholinergic neurotransmission, we determined the effect of VIP, α-chymotrypsin and VIP-Ab on ACh release from ferret trachea in vitro using [3H]-choline as a marker for ACh (Alberts et al., 1982; Wessler et al., 1991).

Methods

Male ferrets (Regal Rabbits, Great Bookham, Surrey, U.K.) weighing 1.0–2.0 kg were used throughout and were kept four to five in a room. They were allowed 1 week to recuperate after delivery and had free access to food and water. They were terminally anaesthetized with pentobarbitone sodium (Sagatal: 60 mg kg−1, i.p.), bled by incising the left ventricle, and the tracheae were removed and bathed in aerated (95% O2+5% CO2) Krebs-Henseleit solution of the following composition (mM): NaCl 118, KCl 5.9, MgSO4 1.2, CaCl2 2.5, NaHCO3 25.5 and glucose 5.05 until required (∼10 min) for study of either mucus secretion or acetylcholine release.

Tracheal preparation for measurement of mucus secretion

Our methodology for measurement of mucus secretion has been described in detail previously (Meini et al., 1993; Ramnarine et al., 1994). Tracheae were cut longitudinally through the dorsal membrane, opened flat and cut transversely to give four segments. Each segment was pinned and clamped across the aperture separating the two halves of perspex Ussing-type chambers so that the tissue divided the chambers into a ‘luminal' (i.e. mucus-producing) and ‘submucosal' side. The chambers were rectangular in cross-section to ensure optimal use of the tissue with an exposed surface area for each segment of 1.12 cm2. Each side of the tissue was bathed with 5 ml warmed (37°C) Krebs-Henseleit solution which was oxygenated (95% O2 : 5% CO2) and circulated using gas-lift pumps.

Radiolabelling of newly synthesized mucus

At time 0 h, Na235SO4 (0.1 mCi) was added to the submucosal half-chambers, in order to label newly-synthesized intracellular mucus, where it remained throughout the experiment. At unit time intervals, the fluid in the luminal side of the chamber (containing secretions) was collected and replaced with fresh Krebs-Henseleit solution. Baseline stability of spontaneous output of 35SO4-labelled macromolecules was reached after taking four 30 min collections followed by two 15 min collections (i.e. over 2.5 h following addition of radiolabel). After stabilization, drugs or control solutions were added and the tissues were electrically stimulated (see Protocols for secretory studies below).

Electrical stimulation

The tracheal segments could be subjected to an electrical current to stimulate excitable tissues (e.g. nerves). Two pins piercing the tissue on either side were connected via outlet wires through the chambers to a Grass stimulator (model S88; Grass Instruments, Quincy, U.S.A.) (Borson et al., 1984). Tissues were stimulated at 2.5 or 10 Hz, 50 V, 0.5 ms for the first 5 min of a 15 min incubation period.

Measurement of 35SO4 output

Luminal fluid, approximately 4 ml and comprising secretions in Krebs-Henseleit solution, was drained into tubes containing 5 g guanidine hydrochloride to dissolve the mucus. The final concentration of guanidine hydrochloride in the fluid was 6 M. Following this, each sample was exhaustively dialyzed against distilled water containing excess Na2SO4 and sodium azide (10 mg l−1) using cellulose tubing (Medicell International Ltd., London, U.K.) which allowed molecules of 12–14 kDa or less to pass through. The sodium azide was present to inhibit bacterial growth. The samples were recovered after at least six changes of distilled water when the radioactive count of the dialysis water was the same after dialysis as before dialysis (∼20 disintegrations per min [d.p.m.]). The recovered samples were weighed and the remaining radioactivity in 1 ml duplicates of each sample mixed with 2 ml scintillant (Ultima Gold XR, Canberra Packard Ltd., Pangbourne, Berkshire, U.K.) was determined by scintillation spectrometry (model 1900CA Spectrophotometer, Canberra Packard Ltd.). The total radioactivity of each sample was estimated by multiplying the radioactivity present in a 1 ml aliquot of sample by the total weight of the sample (assuming a 1 ml sample weighs 1 g).

Protocols for secretory studies

To investigate the effect of exogenous VIP on non-neural mucus secretion, concentration-response and time course studies of VIP were carried out. The first collection at 2.25 h was the baseline control after which VIP (1 nM–10 μM) or vehicle (distilled water) were added to the submucosal chamber where they remained for the duration of the experiment.

To validate the effectiveness of VIP-Ab in neutralizing the secretory response induced by exogenous VIP, VIP-Ab (final dilution 1 : 500; Shimura et al., 1988) or control serum was added to the submucosal chamber 30 min prior to the administration of VIP (10 nM–10 μM).

To examine the effects of endogenous VIP in regulating cholinergic neural secretion, VIP-Ab (1 : 500) or control serum, the putative VIP1 receptor antagonist, [D-p-Cl-Phe6,Leu17]-VIP (0.5 or 5 μM) (Usdin et al., 1994), or α-chymotrypsin (2 u ml−1) were added to the submucosal chamber 30 min before and during electrical stimulation (2.5 or 10 Hz, 50 V, 0.5 ms for 5 min) in the presence of phentolamine, propanolol (10 μM for each), and the tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonist CP-99,994 (3 μM; McLean et al., 1993) to remove α-adrenergic, β-adrenergic and tachykininergic neural influences respectively.

To examine the effects of exogenous VIP on cholinergic neural secretion, VIP or control vehicle was added to the submucosal chamber 30 min before and during 2.5 or 10 Hz stimulation in the presence of phentolamine, propanolol and CP-99,994 (as above). In addition, in the studies investigating the effect of VIP on ACh release, epithelially-scraped tissues were used in the presence of indomethacin (see below). To assess the influence of this treatment on secretion, the effect of 10 Hz cholinergic stimulation (in the presence of adrenoceptor and NK1 receptor blockade; as above) was compared between tissues not scraped and without indomethacin, and tissues scraped in the presence of indomethacin (10 μM).

To determine the effects of endogenous VIP on tachykininergic neural secretion, VIP-Ab (1 : 500) or control serum was added to the submucosal chamber 30 min prior to and during 2.5 or 5 Hz stimulation in the presence of phentolamine, propanolol and atropine (10 μM each) to eliminate adrenergic and cholinergic neural influences.

To study the effects of exogenous VIP in modulating tachykininergic neural secretion, VIP (1 μM) was added to the submucosal chamber 30 min before and during 10 Hz stimulation in the presence of phentolamine, propanolol and atropine (10 μM each).

To assess the contribution of endogenous VIP to NANC non-tachykininergic neural secretion, VIP-Ab was added to the submucosal side for 30 min before and during stimulation at 2.5 or 10 Hz in the presence of atropine, phentolamine, propanolol (10 μM each) and CP-99,994 (3 μM).

To test whether or not the post-junctional secretory responses induced by ACh or SP were affected by VIP or VIP-Ab, ACh (1 μM) or SP (1 μM) was added to the luminal chamber in the presence of VIP (1 μM), VIP-Ab or control serum for 30 min.

To investigate the involvement of, and determine the class of, K+ channels in VIP-regulation of cholinergic neural secretion (i.e. electrical stimulation in the presence of phentolamine, propanolol and CP-99,994; as above), vehicle solution, glibenclamide (0.1 μM), apamin (1 μM) or iberiotoxin (3 μM) were added to the luminal half-chamber 15 min before VIP (10 nM), which in turn was added 30 min before 10 Hz stimulation.

Tracheal preparation for measurement of ACh release

Release of ACh from cholinergic nerves was measured as described previously (Ward et al., 1993; Patel et al., 1995). Tracheae were bathed in Krebs-Henseleit solution, opened longitudinally by cutting anteriorly through the cartilage, and the epithelium was carefully peeled off. Strips of smooth muscle were dissected from the tracheae and as much cartilage as possible was removed. Indomethacin (10 μM) was present in the Krebs-Henseleit solution throughout to prevent the formation of endogenous prostanoids which have been demonstrated previously to affect cholinergic neurotransmission and ACh release (Walters et al., 1984; Deckers et al., 1989; Wessler et al., 1990; Belvisi et al., 1996). The tracheal segments (∼1×5 mm) were suspended top and bottom with silver wire (Goodfellows Metals, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, U.K.), mounted in perfusion chambers, and superfused with Krebs-Henseleit solution, bubbled with 95% O2, 5% CO2 at 37°C at 1 ml min−1 via a perfusion pump (model 503S; Smith and Nephew Watson-Marlow, Falmouth, Cornwall, U.K.).

Loading with [3H]-choline

The tracheal strips were allowed to equilibrate during a 30-min period of continuous superfusion with Krebs-Henseleit solution, and electrical stimulation (4 Hz, 40 V, 0.5 ms) was applied for the last 10 min of this period (model S88 stim-ulator; Grass Instrument Co.) via the silver wires. Tissues were then immersed in 1.5 ml oxygenated Krebs-Henseleit solution containing [methyl-3H]-choline chloride (67 nmol liter−1; specific radioactivity 2.78 TBq mmol−1) and electrically stimulated for another 45 min to allow uptake of [3H]-choline into the tissues. At the end of this period, superfusion was continued with Krebs-Henseleit solution containing hemicholinium-3 (10 μM) to prevent further uptake of [3H]-choline into the tissues. Tissues were then washed for 2.5 h to reach a stable baseline of [3H] release before beginning collections for the experiment (see Protocols below). The single term ‘[3H]' is used herein to acknowledge that the precise identity of the molecule to which the released [3H] is bound is unknown (choline, ACh or phosphorylcholine; see Wessler et al., 1990, 1991). Radioactivity in 1 ml aliquoted sample mixed with 4 ml scintillant (Pico-Fluor 40, Canberra Packard Ltd., Pangbourne, Berkshire, U.K.) was determined by scintillation spectrometry (Model 1900CA Spectrophotometer, Canberra Packard Ltd.).

Protocols for [3H] release studies

Each tracheal tissue segment was stimulated twice (once at 19 min and once at 56 min after equilibration) at 2.5 or 10 Hz, 50 V, 0.5 ms for 1 min, to provoke [3H] overflow. VIP (10 nM and 0.1 μM), VIP-Ab (1 : 500), α-chymotrypsin (2 u ml−1) or control solutions were administered 30 min before the second stimulation. In certain experiments, iberiotoxin (0.1 μM) was added 5 min before the administration of VIP. Samples were collected every minute for 3 min before stimulation, for the 1 min of stimulation, every minute for 3 min after stimulation, and at 5 min intervals outside these times.

Drugs and chemicals.

The following drugs were used: VIP (porcine; synthetic), substance P, [D-p-Cl-Phe6,Leu17]-VIP (human, porcine, rat; synthetic), α-chymotrypsin, acetylcholine, dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO), indomethacin, tetrodotoxin (TTX) and hemicholinium-3 (Sigma Chemical Company Ltd., Poole, Dorset, U.K.); atropine sulphate (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Pharma Hameln, G.m.b.H., Germany); phentolamine mesylate (Ciba Laboratories, Horsham, West Sussex, U.K.); propranolol hydrochloride (Imperial Chemical Industries Ltd., Macclesfield, Cheshire, U.K.); Na235SO4 and [methyl-3H]-choline chloride (Amersham International plc, Amersham, Berkshire, U.K.); and pentobarbitone sodium B.P. (Sagatal; RMB Animal Health Ltd., Dagenham, Essex, U.K.). CP-99,994 (2S,3S)-3-(2-methoxybenzyl)-amino-2-phenyl-piperidine was a kind gift from Pfizer, Groton, U.S.A. (courtesy Dr R. Michael Snider). VIP-Ab was a rabbit anti-VIP (human, porcine, rat) anti-serum, without cross-reactivity to VIP 1-12 (human, porcine, rat), peptide histidine methionine (PHM)-27 (human), substance P, endothelin-1 (human, porcine, canine, rat, mouse, bovine), secretin (porcine), glucagon (human), galanin (rat), somatostatin, pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP)-38 (human, bovine, rat) or PACAP-38 (16–38) (human, bovine, rat), and with little cross-reactivity to VIP 10–28 (human, porcine, rat) (4.4%) or PACAP-27 (human, bovine, rat) (0.02%) (Pennisula Laboratories, Inc., Belmont, U.S.A.).

Data analysis

In Results, data for mucus secretion are the arithmetic mean and one standard error of the mean (s.e.mean). Because baseline d.p.m. displayed variability between tracheal segments, responses obtained from individual segments were calculated as percentage changes in radiolabel output for the difference between response to drug or electrical stimulation and the proceeding collection. Data for ACh release are rate changes for the second stimulation compared with the first stimulation, with the rate coefficient the fractional release of initial [3H] content over time. The concentration of VIP causing a 50% increase (EC50) in secretion or inhibition (IC50) of neurogenic secretion was calculated by non-linear regression using GraphPad Prism software (Microsoft, San Diego, U.S.A.). Significance of changes in 35SO4 output and [3H]-choline overflow, pre- and post-drug or electrical stimulation, were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U-test between two groups, or the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunns multiple comparison test for multiple groups. The null hypothesis was rejected at P<0.05 (two-tail).

Results

Median baseline radioactivity in the secretion studies was of the order of 740 d.p.m. (range 387–1272 d.p.m., depending upon the specific experiment). There were no significant differences between treatment groups.

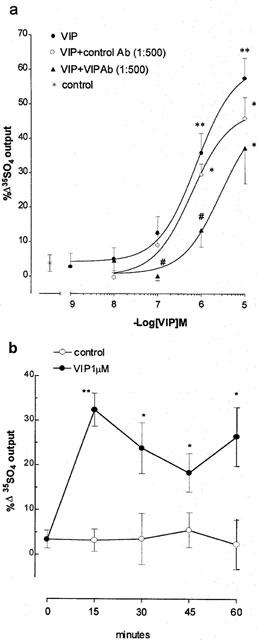

Effect of exogenous VIP on mucus secretion

VIP (1 nM–10 μM) caused an increase in 35SO4 output in ferret tracheal segments during the 15 min incubation period after addition. The increase was concentration-dependent with an approximate EC50 of 0.9 μM and a maximal increase of 53% above control at 10 μM (Figure 1a). In the continued presence of VIP (1 μM) in the submucosal side, 35SO4 output peaked during the first 15 min incubation and, although showing a reduced response, was increased significantly above controls for at least 60 min (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Effect of exogenous vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) on mucus secretion in ferret trachea in vitro. (a) Concentration-response and inhibition by VIP antibody (VIP-Ab), (b) time course. Data are mean per cent change in output of macromolecules labelled in situ with 35SO4 (a marker for mucus) for 5–8 animals per group; vertical bars are one s.e.mean. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared with baseline control (a), or with corresponding vehicle control time point (b); #P<0.05 compared with VIP group (a).

Effects of VIP-Ab on VIP-induced secretion, and cholinergic and tachykininergic neural mucus secretion

Preincubation for 30 min with VIP-Ab caused a rightward shift in the VIP concentration-response curve with significant inhibitions of 90 and 70% respectively at 0.1 and 1 μM VIP (Figure 1a). Control serum had no significant inhibitory effect on VIP-induced 35SO4 output (Figure 1a).

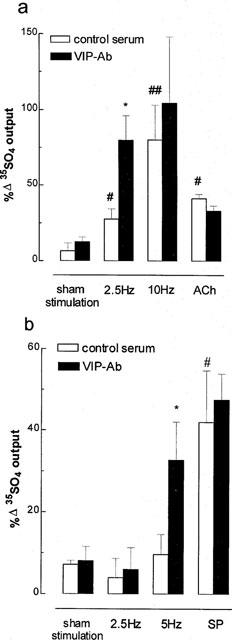

In the presence of phentolamine, propanolol (10 μM each) and CP-99,994 (3 μM), both 2.5 and 10 Hz (50 V, 0.5 ms for 5 min) stimulation significantly induced cholinergic 35SO4 output by 21 and 73% respectively above pre-stimulation controls (Figure 2a). VIP-Ab significantly potentiated cholinergic 35SO4 output by 219% at 2.5 Hz, but had no significant effect at 10 Hz (an increase of 25% above the stimulated value). VIP-Ab did not affect 35SO4 output elicited by exogenous ACh (1 μM), of an equivalent magnitude to that elicited by 2.5 Hz electrical stimulation (Figure 2a). The putative VIP1 receptor antagonist, [D-p-Cl-Phe6,Leu17]-VIP (0.5 or 5 μM), did not alter the magnitude of cholinergic 35SO4 output at 2.5 or 10 Hz stimulation, nor did it affect exogenous VIP-elicited 35SO4 output. α-Chymotrypsin (2 u ml−1) itself caused a significant increase in 35SO4 output of 40% above control (n=6, P<0.05). Neither the VIP receptor antagonist nor α-chymotrypsin were utilized further to evaluate the role of endogenous VIP in neurogenic secretion.

Figure 2.

Effect of endogenous vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) on neurogenic mucus secretion in ferret trachea in vitro. (a) Effect on cholinergic secretion. A VIP antibody (VIP-Ab, 1 : 500 dilution) was used to exclude VIP, and phentolamine, propanolol (10 μM each) and the tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonist CP-99,994 (3 μM) were used to exclude adrenergic and tachykininergic neural influences at stimulation parameters of 2.5 or 10 Hz, 50 V, 0.5 msec for 5 min. ACh, acetylcholine (1 μM). (b) Effect on tachykininergic neural secretion. VIP antibody (1 : 500 dilution) was used to exclude VIP, and phentolamine, propanolol and atropine (10 μM each) were used to exclude adrenergic and cholinergic influences at stimulation parameters of 2.5 or 5 Hz, 50 V, 0.5 msec for 5 min. SP, substance P (1 μM). Data are mean per cent change in output of macromolecules labelled in situ with 35SO4 (a marker for mucus) for 5–7 animals per group; vertical bars are one s.e.mean. *P<0.05 compared with serum control group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 compared with sham stimulation group.

In the presence of atropine, phentolamine and propanolol (10 μM each), VIP-Ab significantly enhanced tachykininergic 35SO4 output by 237% above serum controls at 5 Hz stimulation (Figure 2b). VIP-Ab did not affect 35SO4 output induced by SP (1 μM) (Figure 2b).

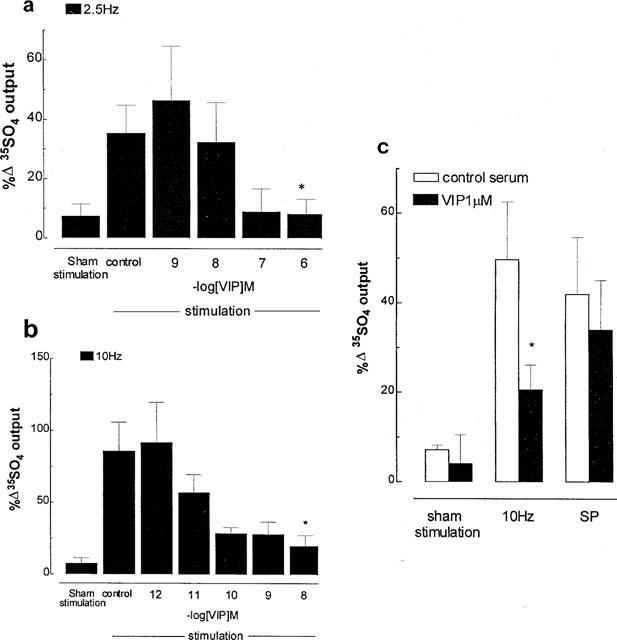

Effect of exogenous VIP on cholinergic and tachykininergic neural mucus secretion

In the presence of phentolamine, propanolol (10 μM each) and CP-99,994 (3 μM), exogenous VIP inhibited cholinergic 35SO4 output: at 2.5 Hz stimulation with complete inhibition at 1 μM (Figure 3a), and at 10 Hz with a maximal inhibition of 80% at 10 nM (Figure 3b). In contrast, exogenous VIP (1 μM) had an additive effect with ACh in increasing 35SO4 output (41±3% increase with ACh alone vs 78±9% increase with ACh+VIP, P<0.05). Epithelial scraping and indomethacin had no significant effect on cholinergic 35SO4 output compared with non-scraped tissues without indomethacin: respectively 13±10% vs 8±9% increase in output in sham stimulated tissues, 227±30% vs 245±25% in stimulated tissues, 62±18% vs 96±20% in stimulated tissues in the presence of VIP (10 nM) (n=4 for each group).

Figure 3.

Effect of exogenous vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) on neurogenic mucus secretion in ferret trachea in vitro. (a and b) Effect on cholinergic neural secretion. Phentolamine, propanolol (10 μM each) and the tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonist CP-99,994 (3 μM) were used to exclude adrenergic and tachykininergic influences at stimulation parameters of 2.5 (a) or 10 Hz (b), 50 V, 0.5 msec for 5 min. (c) Effect on tachykininergic neural secretion. Phentolamine, propanolol and atropine (10 μM each) were used to exclude adrenergic and cholinergic influences at stimulation parameters of 10 Hz, 50 V, 0.5 msec for 5 min. SP, substance P (1 μM). Data are mean per cent change in output of macromolecules labelled in situ with 35SO4 (a marker for mucus) for 5–7 animals per group; vertical bars are one s.e.mean. *P<0.05 compared with stimulation control group (a and b), or with serum control group (c).

In the presence of atropine, phentolamine and propanolol (10 μM each), 10 Hz stimulation caused an increase in tachykininergic 35SO4 output of 42% above pre-stimulation values, which was inhibited by exogenous VIP (1 μM) by 59% (Figure 3c). In contrast, SP (1 μM)-induced increase in 35SO4 output was not significantly changed by pre-treatment with VIP (1 μM) (Figure 3c).

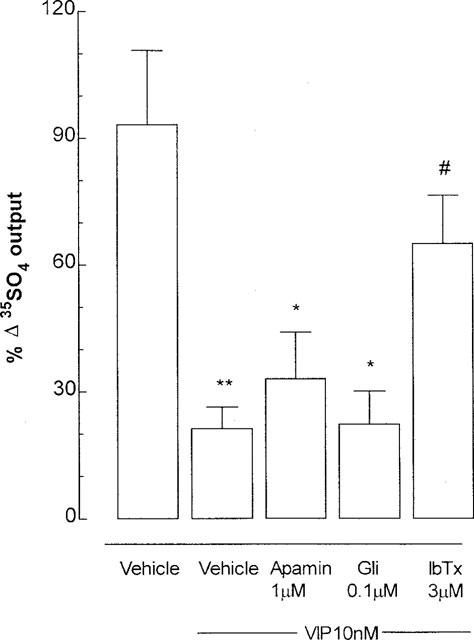

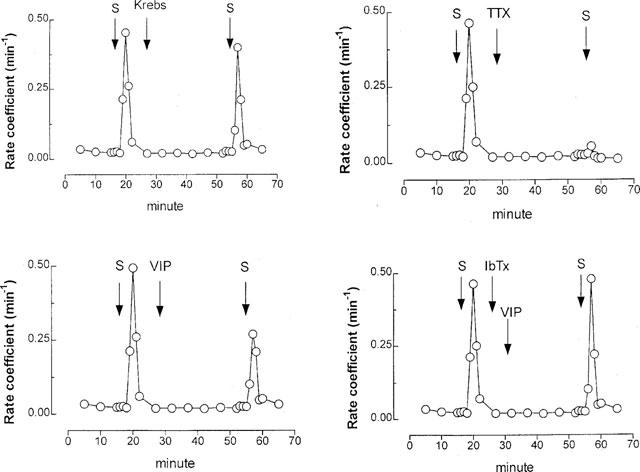

Effect of K+ channel blockers on cholinergic neural secretion

In the presence of phentolamine, propanolol (10 μM each) and CP-99,994 (3 μM), exogenous VIP (1 μM) significantly diminished 10 Hz cholinergic secretion by 79% compared with stimulation control, and this effect was reversed (by 60%) by pre-incubation with iberiotoxin (3 μM), but not by apamin (1 μM ) or glibenclamide (0.1 μM) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Inhibition by exogenous vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) of cholinergic neural mucus secretion in ferret trachea in vitro, and the effect of potassium (K+) channel blockers. Phentolamine, propanolol (10 μM each) and the tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonist CP-99,994 (3 μM) were used to exclude adrenergic and tachykininergic influences at stimulation parameters of 10 Hz, 50 V, 0.5 msec for 5 min. Gli: glibenclamide, ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channel inhibitor); apamin, small conductance calcium-activated K+ (SKca) channel blocker; IbTx: iberiotoxin, large conductance calcium-activated K+ (BKca) channel blocker. Data are mean per cent change in output of macromolecules labelled in situ with 35SO4 (a marker for mucus) for 5–6 animals per group; vertical bars are one s.e.mean. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared with stimulation control group; #P<0.05 compared with VIP + vehicle group.

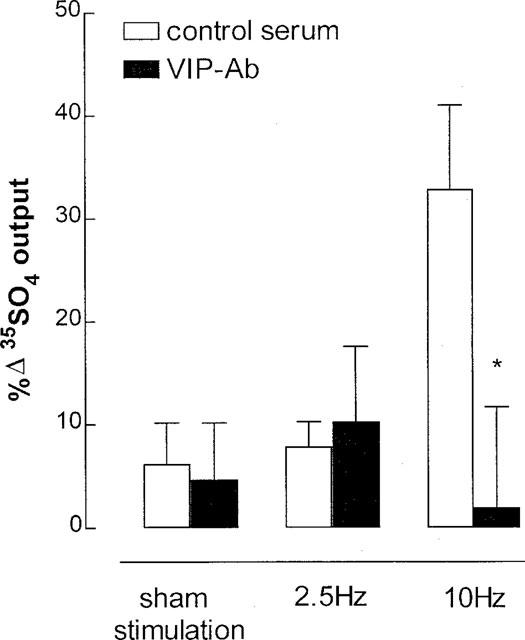

Effect of VIP-Ab on NANC, non-tachykininergic neural mucus secretion

In the presence of atropine, phentolamine, propanolol (10 μM each) and CP-99,994 (3 μM), 10 Hz stimulation significantly increased 35SO4 output by 25% above pre-stimulation control, whereas stimulation at 2.5 Hz did not significantly increase 35SO4 output (Figure 5). The 10 Hz stimulation-induced 35SO4 output was eliminated by VIP-Ab (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Endogenous vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) as mediator of NANC, non-tachykininergic neural mucus secretion in ferret trachea in vitro. A VIP antibody (VIP-Ab, 1 : 500 dilution) was used to exclude VIP, and phentolamine, propanolol, atropine (10 μM) and the tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonist CP-99,994 (3 μM) were used to exclude adrenergic, cholinergic and tachykininergic influences at stimulation parameters of 2.5 or 10 Hz, 50 V, 0.5 msec for 5 min. Data are mean per cent change in output of macromolecules labelled in situ with 35SO4 (a marker for mucus) for six animals per group; vertical bars are one s.e.mean. *P<0.05 compared with serum control group.

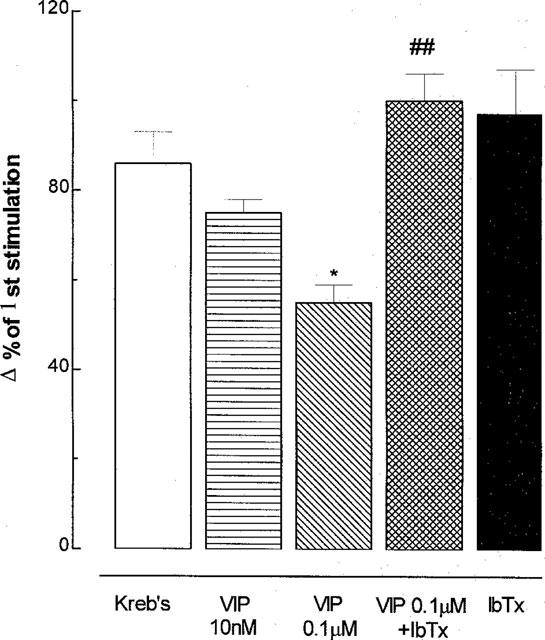

Effects of VIP and iberiotoxin on cholinergic neural [3H] output

Exogenous VIP (0.1 μM) significantly reduced [3H] overflow at 10 Hz stimulation by 34% compared with control (Figures 6 and 7). This effect was completely reversed by pre-administration of iberiotoxin (0.1 μM) (Figures 6 and 7). Iberiotoxin alone had no significant effect on stimulated [3H] output (Figure 7). Tetrodotoxin (3 μM) markedly inhibited (by ∼90%) the [3H] overflow evoked by 10 Hz stimulation (Figure 6): mean 10% (±12%) change in [3H] overflow compared with first stimulation (n=5, P<0.01).

Figure 6.

Effect of 10 Hz stimulation (50 V, 0.5 msec, 5 min) on acetylcholine (ACh) release by ferret tracheal strips in vitro. Tissues were pre-incubated with [3H]-choline chloride (a marker for ACh) and stimulated electrically (S). Each panel gives the rate of [3H] overflow for an individual tracheal strip. VIP, vasoactive intestinal peptide (0.1 μM); TTX, tetrodotoxin (0.1 μM); IbTx, iberiotoxin (0.1 μM).

Figure 7.

Involvement of large-conductance K+ (BKCa) channels in vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP)-inhibition of acetylcholine (ACh) release in ferret tracheal strips in vitro. IbTx, iberiotoxin (0.1 μM); BKCa channel blocker. Tissues were pre-incubated with [3H]-choline chloride (a marker for ACh) and stimulated electrically at 10 Hz, 50 V, 5 msec for 5 min. Data are mean per cent change in rate of [3H] overflow at a second stimulation compared with the first stimulation for 5–6 animals per group; vertical bars are one s.e.mean. *P<0.05 compared with Kreb's solution alone; ##P<0.01 compared with VIP+IbTx group.

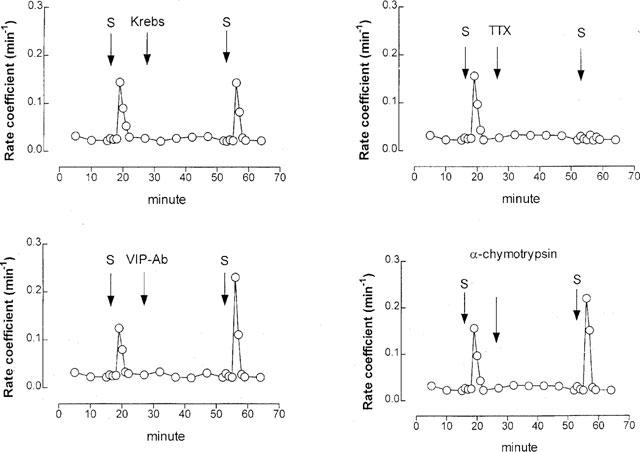

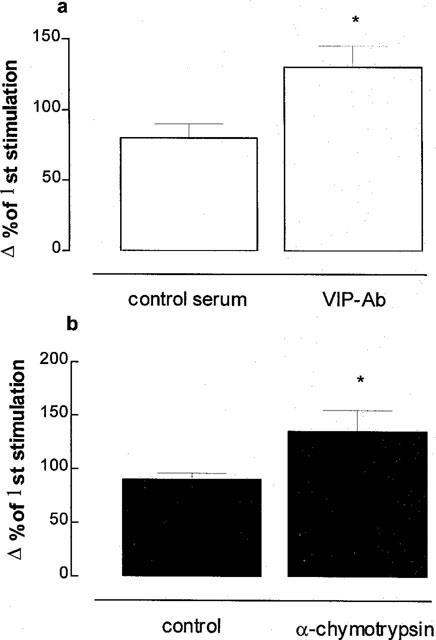

Effects of VIP-Ab and α-chymotrypsin on cholinergic neural [3H] output

Pre-treatment with VIP-Ab (1 : 500) or α-chymotrypsin (2 u ml−1) potentiated neural [3H] output at 2.5 Hz by 44 and 40%, respectively (Figures 8 and 9). Tetrodotoxin (3 μM) markedly inhibited (by ∼95%) the [3H] overflow evoked by 2.5 Hz stimulation (Figure 8): mean 5% (±10%) change in [3H] overflow compared with first stimulation (n=5, P<0.01).

Figure 8.

Effect of 2.5 Hz stimulation (50 V, 0.5 msec, 5 min) on acetylcholine (ACh) release in ferret tracheal strips in vitro. Tissues were pre-incubated with [3H]-choline chloride (a marker for ACh) and stimulated electrically (S). Each panel gives the rate of [3H] overflow for an individual tracheal strip. VIP-Ab, antibody to vasocative intestinal peptide (1 : 500 dilution); TTX, tetrodotoxin (0.1 μM); α-chymotrypsin (2 u ml−1).

Discussion

In the present study in ferret trachea in vitro, exogenous VIP increased 35SO4-labelled mucus output whereas endogenous VIP regulated the magnitude of neurogenic secretion. The increase in 35SO4 output is consistent with an increase in mucus secretion by submucosal glands, because there are few surface epithelial goblet cells but large numbers of submucosal glands in ferret trachea (Robinson et al., 1986; Meini et al., 1993). By autoradiography, under basal conditions there is selective uptake and retention of 35SO4 by tracheal submucosal glands, rather than epithelium, in cat (Davies et al., 1990) and ferret (Gashi et al., 1987), with some labelling of cartilage. Stimulation of ferret trachea in vitro increased radioactive counts in the incubation medium, with concomitant loss of autoradiographic grains from the glands (Gashi, 1987): neither cartilage nor epithelium showed loss of grains. In cats, tracheal washings labelled with 35SO4 have a molecular weight and buoyant density typical of a mucin molecule (Davies et al., 1990). Thus, the increased output of 35SO4 observed herein is indicative of an increase in tracheal submucosal gland mucus secretion.

We demonstrated herein that exogenous VIP caused a small increase in secretion in a concentration-dependent fashion with an increase of 32% above control at 1 μM. This observation is consistent with previous reports showing that VIP induces release of a variety of mucus markers with similar potency (maximal/near maximal effects at ∼1 μM) in a number of different in vitro airway preparations: ferret trachea (Peatfield et al., 1983; Gashi et al., 1986), cat isolated tracheal submucosal glands (Shimura et al., 1988), rat trachea (Wagner et al., 1998) and human nasal mucosal explants (Baraniuk et al., 1990; Mullol et al., 1992). VIP also stimulated rhinorrhea in vivo in human volunteers (Chatelain et al., 1995). With secretory activity apparent at ∼1 μM, it has to be concluded that VIP is not a potent secretagogue. However, it would appear from the present study that the activity of VIP is related primarily to neuroregulation of airway secretion rather than to induction of secretion. The VIP-induced increase in mucus secretion found herein was inhibited by a VIP-Ab. VIP-Ab has previously been shown to inhibit the potentiation by VIP of methacholine-elicited [3H]-glycoconjugate release by cat isolated submucosal glands (Shimura et al., 1988), and to inhibit smooth muscle relaxation induced by i-NANC electrical stimulation in cat and guinea-pig trachea, a response mediated by VIP (Li & Rand, 1991). Taken together, airway responses to exogenous and endogenous VIP are effectively suppressed by VIP-Ab, making it a useful tool for investigating the biological role of endogenous VIP. α-Chymotrypsin is a peptidase which has also been used to investigate the effect of endogenous VIP. For example, α-chymotrypsin greatly reduced the relaxant response to exogenous VIP and to NANC electrical stimulation in guinea-pig tracheal smooth muscle (Ellis & Farmer, 1989a; Tucker et al., 1990; Li & Rand, 1991), which gave support to the notion that VIP is a neurotransmitter of the i-NANC nervous system in guinea-pig airways. However, in the present study, we found that α-chymotrypsin itself caused an increase in 35SO4 output which precluded its use in characterizing the role of exogenous VIP on secretion, and of endogenous VIP on neurogenic secretion. In the present study, a putative VIP1 antagonist, [D-p-Cl-Phe6,Leu17]-VIP, did not alter the magnitude of cholinergic neural secretion nor did it diminish exogenous VIP-induced mucus secretion. This antagonist has variable effects depending upon species and preparation (Ellis & Farmer, 1989b; Aizawa et al., 1994; Shvilkin et al., 1994), but is not suitable for investigating the role of endogenous VIP in neurogenic mucus secretion in ferret trachea.

Figure 9.

Effect of endogenous vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) on acetylcholine (ACh) release in ferret tracheal strips in vitro. A VIP antibody (VIP-Ab, 1 : 500 dilution; a) or α-chymotrypsin (2 u ml−1; b) were used to exclude VIP. Tissues were pre-incubated with [3H]-choline chloride (a marker for ACh) and stimulated electrically at 2.5 Hz, 50 V, 5 msec for 5 min. Data are mean per cent change in rate of [3H] overflow at a second stimulation compared with the first stimulation for five animals per group; vertical bars are one s.e.mean. *P<0.05 compared with control group.

We found herein that exogenous VIP markedly inhibited cholinergic neural secretion at both 2.5 and 10 Hz, and that VIP-Ab potentiated cholinergic neural secretion (at 2.5 Hz). In contrast, exogenous VIP (1 μM) and ACh combined had an additive effect on secretion, whilst VIP-Ab had no significant effect on ACh-induced secretion. These results suggest that VIP regulates prejunctional cholinergic neuro-transmission to mucus secretion in ferret trachea rather than affecting the post-junctional activity of ACh. There is evidence to suggest that VIP regulates cholinergic neurotransmission in guinea-pig and ferret tracheal smooth muscle prejunctionally, post-junctionally or ganglionically. For example, VIP inhibited both ganglionic and post-ganglionic cholinergic contractile responses in an isolated innervated guinea-pig tracheal preparation in response to vagal stimulation or electrical field stimulation (EFS) (Martin et al., 1990). Similarly, VIP inhibited guinea-pig tracheal smooth muscle contraction evoked by EFS, and also decreased ACh-induced contraction (Shigyo et al., 1997). Depending upon concentration, VIP may augment (at 1 pM–1 nM) or suppress (at 10 nM–0.2 μM) cholinergic neurotransmission in ferret tracheal smooth muscle (Sekizawa et al., 1988). VIP also has variable effects on secretion, depending upon stimulus. VIP inhibited maintained methacholine-stimulated mucous gland cell liquid secretion in vitro in ferret trachea, but potentiated maintained phenylephrine-stimulated serous gland cell liquid secretion (Webber & Widdicombe, 1987). In contrast, VIP augmented methacholine-induced [3H]-glycoconjugate secretion from isolated cat tracheal submucosal glands (Shimura et al., 1988). Thus, the conflicting data of the latter two studies, combined with our present data of no inhibitory or potentiating effect for VIP on ACh-induced secretion, indicate that the effect of VIP on cholinomimetic-induced secretion is complex and varies with animal species, study design, and degree of isolation of the glands. It is possible that isolation of the cat gland from the epithelium removes an inhibitory influence (Sasaki et al., 1989). However, in the present study, epithelial scraping did not alter the secretory response to cholinergic nerve stimulation.

In both our present study and the latter study using the isolated cat gland, cyclooxygenase inhibition did not affect stimulated mucus output, which suggests that endogenous prostaglandins do not regulate secretion. Interestingly, depending upon the prostaglandin, exogenous prostaglandins can increase, decrease or have no effect on different parameters of secretion in ferret trachea in vitro (Deffebach et al., 1990). Thus, the data of the latter study combined with the lack of effect of cyclooxygenase discussed above indicate either that prostaglandins are not generated endogenously under the above experimental conditions, or that the opposing effects of different generated prostaglandins leads to an overall lack of secretory response.

We found herein that exogenous VIP significantly suppressed tachykininergic neural secretion at 10 Hz stimulation and VIP-Ab markedly potentiated tachykininergic neural secretion at 5 Hz stimulation. Neither VIP nor VIP-Ab altered the secretory response to exogenous SP. These results suggest that VIP modulates the release of tachykinins via a prejunctional mechanism. A similar conclusion has been reached for VIP-inhibition of tachykininergic contractility of guinea-pig smooth muscle (Stretton et al., 1991). VIP also inhibited SP-induced ACh release in rabbit tracheal smooth muscle strips (Giuseppe et al., 1995).

In the presence of atropine, propanolol, phentolamine and CP-99,994 (i.e. NANC, non-tachykininergic), 10 Hz stimulation evoked a significant increase in mucus secretion of 25% above control, which was abolished by VIP-Ab indicating that VIP was the mediator of the response. It is interesting that the magnitude of the response was equivalent to that induced by exogenous VIP (1 μM). The concentration of VIP in the tissues, after release from nerves, is unknown, although local concentrations may be high. However, whatever the concentration near the secretory cells, the small increases in secretion elicited by either exogenous or endogenous VIP do not indicate that VIP is an important airway secretagogue. Rather, neuronal VIP elicits two responses: one is a small stimulatory effect upon mucus secretion, but this is offset by its effect in curbing prejunctional cholinergic and tachykininergic neural secretion.

Incubation with [3H]-choline and subsequent overflow of [3H] can substitute for bioassay methods in the measurement of ACh release from guinea-pig ileum (Alberts et al., 1982) and has been applied to a variety of airway smooth muscle preparations (Wessler et al., 1990, 1991; Ward et al., 1993; Patel et al., 1995). In the present study, tetrodotoxin virtually abolished [3H] overflow evoked by electrical stimulation of ferret tracheal smooth muscle strips which supports the concept that [3H] overflow in our ACh release preparation is of neural origin. We found that exogenous VIP significantly inhibited [3H] overflow, whereas VIP-Ab and α-chymotrypsin augmented [3H] overflow. These data support the contention that endogenous VIP regulates the magnitude of neurogenic tracheal mucus secretion in ferret via inhibition of ACh release.

In this study, we found that the BKca channel inhibitor, iberiotoxin, but not the SKca channel inhibitor, apamin, or the KATP channel inhibitor, glibenclamide, reversed the VIP-inhibition of cholinergic neural secretion. Similarly, iberiotoxin reversed the suppression of ACh release by exogenous VIP. Reversal in both instances was unlikely to be due to any possible potentiating effect of iberiotoxin on neurotransmission because we have shown previously that iberiotoxin has no significant effect on neurogenic mucus output (Ramnarine et al., 1998), and herein did not affect stimulated [3H] overflow. These data suggest that VIP-inhibition of cholinergic neurotransmission is mediated via opening of BKca channels. We have found previously that selective opioid OP1 and OP3 receptor agonists inhibit neurogenic mucus secretion in ferret trachea at a prejunctional site via opening of BKCa channels (Ramnarine et al., 1998).

VIP inhibited glycoconjugate secretion and lysozyme release from normal human tracheal explants. In contrast, in explants with ‘bronchitic' changes, VIP did not inhibit baseline or methacholine-stimulated glycoconjugate release, or mucous or serous cell discharge (Cole et al., 1981). In severe asthma, there is evidence of an imbalance in NANC nerves within the airways; specifically a deficiency of VIP- and an excess of SP-immunoreactive nerves (Ollerenshaw et al., 1989, 1991), but not in symptomatic mild to moderate asthmatics (Howarth et al., 1995). In studies where plasma levels of VIP and SP were correlated with airway function, it was concluded that an over-excitation of excitatory-NANC and a deficiency in i-NANC activity were closely related to asthma attacks and bronchial hyperresponsiveness (Liu et al., 1993a,1993b). Rapid degradation of VIP by a variety of enzymes in asthmatic airways, for example mast cell tryptase (Caughey et al., 1988), and increased plasma levels and affinity of catalytic anti-VIP antibodies in mild to moderate asthmatics (Paul et al., 1995) might contribute to the deficiency in VIP. This might be one explanation for the ineffectiveness of inhaled VIP as a bronchodilator in asthmatics (Barnes & Dixon, 1984).

In conclusion, in ferret trachea in vitro, endogenous VIP regulates cholinergic and tachykininergic neural secretion at a prejunctional site via opening of BKca channels. In the context of mucus secretion, we propose that VIP joins NO as a neurotransmitter of i-NANC neural pathways in ferret trachea.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Asthma Campaign (U.K.) and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan (CMRP520) for financial support. Y.-C. Liu is a recipient of a Biomedicine Scholarship from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- BKCa (channel)

large conductance, calcium-activated potassium (channel)

- CGRP

calcitonin gene-related peptide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulphoxide

- i-NANC

inhibitory non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic

- K+ (channel)

potassium (channel)

- KATP (channel)

adenosine triphosphate sensitive potassium channel

- NANC

non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic

- NKA

neurokinin A

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- NPY

neuropeptide Y

- PACAP

pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide

- PHM

peptide histidine methionine

- SKCa (channel)

small conductance calcium-activated potassium channel

- SP

substance P

- VIP

vasoactive intestinal peptide

- VIP-Ab

vasoactive intestinal peptide antibody

References

- AIZAWA H., INOUE H., SHIGYO M., TAKATA S., KOTO H., MATSUMOTO K., HARA N. VIP antagonists enhance excitatory cholinergic neuro-transmission in the human airway. Lung. 1994;172:159–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00175944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALBERTS P., BARTFAI T., STJARNE L. The effects of atropine on [3H]acetylcholine secretion from guinea-pig myenteric plexus evoked electrically or by high potassium. J. Physiol. 1982;329:93–112. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BANKS B.E.C., BROWN C., BURNSTOCK G.M., CLARET M., COCKS T.M., JENKINSON D.H. Apamin blocks certain neurotransmitter-induced increases in potassium permeability. Nature. 1979;282:415–417. doi: 10.1038/282415a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARANIUK J.N., LUNDGREN J.D., OKAYAMA M., MULLOL J., MERIDA M., SHELHAMER J.H., KALINER M.A. Vasoactive intestinal peptide in human nasal mucosa. J. Clin. Invest. 1990;86:825–831. doi: 10.1172/JCI114780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J. Neuroeffector mechanisms: the interface between inflammation and neuronal responses. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1996;98:1187–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J., DIXON C.M.S. The effect of inhaled vasoactive intestinal peptide on bronchial hyperreactivity in man. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1984;130:162–166. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELVISI M.G., PATEL H.J., TAKAHASHI T., BARNES P.J., GIEMBYCZ M.A. Paradoxical facilitation of acetylcholine release from parasympathetic nerves innervating guinea-pig trachea by isoprenaline. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:1413–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BORSON D.B., CHARLIN M., GOLD B.D., NADEL J.A. Neural regulation of 35SO4-macromolecule secretion from tracheal glands of ferrets. J. Appl. Physiol. 1984;57:457–466. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.2.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOWDEN J.J., GIBBINS I.L. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and neuropeptide Y co-exist in non-adrenergic sympathetic neurons to guinea pig trachea. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1992;38:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(92)90211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAUGHEY G.H., LEIDIG F., VIRO N.F., NADEL J.A. Substance P and vasoactive intestinal peptide degradation by mast cell tryptase and chymase. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988;244:133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHATELAIN C., POCHON N., LACROIX J.S. Functional effects of phosphoramidon and captopril on exogenous neuropeptides in human nasal mucosa. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 1995;252:83–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00168025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLE S.J., SAID S.I., REID L.M. Inhibition by vasoactive intestinal peptide of glycoconjugate and lysozyme secretion by human airways in vitro. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1981;124:531–536. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1981.124.5.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIES J.R., CORBISHLEY C.M., RICHARDSON P.S. The uptake of radiolabelled precursors of mucus glycoconjugates by secretory tissues in the feline trachea. J. Physiol. 1990;420:19–30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp017899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DECKERS I.A., RAMPART M., BULT H., HERMAN A.G. Evidence for the involvement of prostaglandins in modulation of acetylcholine release from bronchial tissue. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;167:415–418. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEFFEBACH M.E., ISLAMI H., PRICE A., WEBBER S.E., WIDDICOMBE J.G. Prostaglandins alter methacholine-induced secretion in ferret in vitro trachea. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;258:L75–L80. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1990.258.2.L75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEY R.D., ALTERMUS J.B., RODD A., MAYER B, , SAID S.I., COBURN R.F. Neurochemical characterization of intrinsic neurons in ferret tracheal plexus. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1996;14:207–216. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.14.3.8845170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEY R.D., HOFFPAUR J., SAID S.I. Co-localization of VIP- and SP-containing nerves in cat bronchi. Neuroscience. 1988;24:275–281. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90330-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEY R.D., SHANNON W.A., JR, SAID S.I. Localization of VIP-immunoreactive nerves in airways and pulmonary vessels of dog, cat and human subjects. Cell Tissue Res. 1981;220:231–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00210505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEY R.D., ZHU W. Origin of galanin in verves of cat airways and colocalization with vasoactive intestinal peptide. Cell Tissue Res. 1994;273:193–200. doi: 10.1007/BF00304626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLIS J.L., FARMER S.G. Effects of peptidases on non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic inhibitory responses of tracheal smooth muscle: a comparison with effects on VIP- and PHI-induced relaxation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1989a;96:521–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLIS J.L., FARMER S.G. The effects of vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) antagonists, and VIP and peptide histidine isoleucine antisera on non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic relaxations of tracheal smooth muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1989b;96:521–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISCHER A.W., HOFFMANN B. Nitric oxide synthase in neurons and nerve fibers of lower airways and in vagal sensory ganglia of man. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996;154:209–216. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.1.8680682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISCHER A., KUMMER W., COURAUD J.-Y., ALDER D., BRANSCHEID D., HEYM C. Immunohistochemical localization of receptors for vasoactive intestinal peptide and substance P in human trachea. Lab. Invest. 1992;67:387–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCIA M.L., GALVEZ A., GARCIA-CALVO M., KING V.F., VASQUEZ J., KACZOROWSKI G.J. Use of toxins to study potassium channels. J. Bioenerget. Biomemb. 1991;23:615–646. doi: 10.1007/BF00785814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GASHI A.A., BORSON D.B., FINKBEINER W.E., NADEL J.A., BASBAUM C.B. Neuropeptides degranulate serous cells of ferret tracheal glands. Am. J. Physiol. 1986;251:C223–C229. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1986.251.2.C223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GASHI A.A., BORSON D.B., FINKBEINER W.E., NADEL J.A., BASBAUM C.B. Neuropeptides degranulate serous cells of ferret tracheal glands. Am. J. Physiol. 1987;251:C2223–C2229. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1986.251.2.C223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIUSEPPE N.C., LOADER J.E., GRAVES J.P., LARSEN G.L. Modulation of acetylcholine release in rabbit airways in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;12:L432–L437. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.3.L432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOWARTH P.H., SPRINGALL D.R., REDINGTON A.E., DJUKANOVIC R., HOLGATE S.T., POLAK J.M. Neuropeptide-containing nerves in endobronchial biopsies from asthmatic and nonasthmatic subjects. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1995;13:288–296. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.3.7654385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAITINEN A., PARTANEN M., HERVONEN A., PELTO-HUIKKO M., LAITINEN L.A. VIP-like immunoreactive nerves in human respiratory tract: light and electronic microscopic study. Histochemistry. 1985;82:313–319. doi: 10.1007/BF00494059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMMERS J.W., BARNES P.J., CHUNG K.F. Nonadrenergic, noncholinergic airway inhibitory nerves. Eur. Respir. J. 1992;5:239–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAZARUS S.C., BASBAUM C.B., BARNES P.J., GOLD W.M. cAMP immunocytochemistry provides evidence for functional VIP receptors in trachea. Am. J. Physiol. 1986;251:C115–C119. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1986.251.1.C115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEROUX P., VAUDRY H., FOURNIER A., ST-PIERRE S., PELLETIER G. Characterization and localization of vasoactive intestinal peptide receptors in the rat lung. Endocrinology. 1984;114:1506–1512. doi: 10.1210/endo-114-5-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI C.G., RAND M.J. Evidence that part of the NANC relaxant response of guinea-pig trachea to electrical field stimulation is mediated by nitric oxide. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;102:91–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU A., LI P.S., ZHANG Z.J. A clinical study on determination of plasma vasoactive intestinal peptide and the relationship between plasma vasoactive intestinal peptide and bronchial responsiveness in asthmatics. Chung Hua Nei Ko Tsa Chih. 1993a;32:165–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU A., LI P.S., ZHANG Z.J. A clinical study on the effect of non-adrenergic non-cholinergic nerves in asthma. Chung Hua Nei Ko Tsa Chih. 1993b;32:223–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN J.G., WANG A., ZACOUR M., BIGGS D.F. The effects of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide on cholinergic neurotransmission in an isolated innervated guinea pig tracheal preparation. Respir. Physiol. 1990;79:111–121. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(90)90011-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLEAN S., GANONG A., SEYMOUR P.A., SNIDER R.M., DESAI M.C., ROSEN T., BRYCE D.K., LONGO K.P., REYNOLDS L.S., ROBINSON G., SCHMIDT A.W., SIOK C., HEYM J. Pharmacology of CP-99,994: a non-peptide antagonist of the tachykinin neurokinin-1 receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993;267:472–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEINI S., MAK J.C.W., ROHDE J.A.L., ROGERS D.F. Tachykinin control of ferret airways: mucus secretion, bronchoconstriction and receptor mapping. Neuropeptides. 1993;24:81–89. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(93)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULLOL J., RIEVES R.D., BARANIUK J.N., LUNDGREN J.D., MERIDA M., HAUSFELD J.M., SHELHAMER J.H., KALINER M.A. The effects of neuropeptides on mucous glycoprotein secretion from human nasal mucosa in vitro. Neuropeptides. 1992;21:231–238. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(92)90027-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIKI I., KELLY R.P., ASHCROFT S.J.H., ASHCROFT F.M. ATP-sensitive K-channels in HIT T15 β-cells studies by patch-clamp methods, 86Rb efflux and glibenclamide binding. Pflügers Arch. 1989;415:47–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00373140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLLERENSHAW S.J., JARVIS D., SULLIVAN C.E., WOOLCOCK A.J. Substance P immunoreactive nerves in airways from asthmatics and non-asthmatics. Eur. Respir. J. 1991;4:673–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLLERENSHAW S.J., JARVIS D., WOOLCOCK A., SULLIVAN C., SCHEIBNER T. Absence of immunoreactive vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in tissue from the lungs of patients with asthma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989;320:1244–1248. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198905113201904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATEL H.J., BARNES P.J., TAKAHASHI T., TADJKARIMI S., YACOUB M.H., BELVISI M.G. Evidence for pre-junctional muscarinic autoreceptor in human and guinea-pig trachea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995;152:872–878. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAUL S., GAO Q.S., HUANG H., SUN M., THOMPSON A., RENNARD S., LANDER D. Catalytic autoantibodies to vasoactive intesinal peptide. Chest. 1995;107:S125–S126. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.3_supplement.125s-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEATFIELD A.C., BARNES P.J., BRATCHER C., NADEL J.A., DAVIS B. Vasoactive intestinal peptide stimulates tracheal submucosal gland secretion in ferret. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1983;128:89–93. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.128.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAMNARINE S.I., HIRAYAMA Y., BARNES P.J., ROGERS D.F. Sensory-efferent neural control of mucus secretion: characterisation using tachykinin receptor antagonists in ferret trachea in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;113:1183–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAMNARINE S.I., KHAWAJA A.M., BARNES P.J., ROGERS D.F. Nitric oxide inhibition of basal and neurogenic mucus secretion in ferret trachea in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:998–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAMNARINE S.I., LIU Y.-C., ROGERS D.F. Neuroregulation of mucus secretion by opioid receptors and KATP and BKCa channels in ferret trachea in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123:1631–1638. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAMNARINE S.I., ROGERS D.F. Non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic neural control of mucus secretion in the airways. Pulm. Pharmacol. 1994;7:19–33. doi: 10.1006/pulp.1994.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBINSON N.P., VENNING L., KYLE H., WIDDICOMBE J.G. Quantitation of the secretory cells of the ferret tracheobronchial tree. J Anat. 1986;145:173–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROGERS D.F.Neural control of airway secretions Autonomic Control of the Respiratory System 1997Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers GmbH; 201–227.ed. Barnes, P.J., pp [Google Scholar]

- SASAKI T., SHIMURA S., SASAKI H, TAKISHIMA T. Effect of epithelium on mucus secretion from feline tracheal submucosal glands. J. Appl. Physiol. 1989;60:1237–1247. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.2.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMID-ANTOMARCHI H., AMOROSO S., FOSSET M., LAZDUNSKI M. K+ channel openers activate brain sulfonylurea-sensitive K+ channels and block neurosecretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:3489–3492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEKIZAWA K., TAMAOKI J., GRAF P.D., NADEL J.A. Modulation of cholinergic neurotransmission by vasoactive intestinal peptide in ferret trachea. J. Appl. Physiol. 1988;64:2433–2437. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.6.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIGYO M., AIZAWA H., KOTO H., MATSUMOTO K., TAKATA S., HARA N. Pre- and post-junctional effects of VIP-like peptides in guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle. Respiration. 1997;64:59–65. doi: 10.1159/000196644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIMURA S., SASAKI T., IKEDA K., SASAKI H., TAKISHIMA T. VIP augments cholinergic-induced glycoconjugate secretion in tracheal submucosal glands. J. Appl. Physiol. 1988;65:2437–2544. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.6.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHVILKIN A., DANILO P., JR, CHEVALIER P., CHANG F., COHEN I.S., ROSEN M.R. Vagal release of vasoactive intestinal peptide can promote vagotonic tachycardia in the isolated innervated rat heart. Cardiovas. Res. 1994;28:1769–1773. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.12.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STRETTON C.D., BELVISI M.G., BARNES P.J. Modulation of neural bronchoconstrictor responses in the guinea pig respiratory tract by vasoactive intestinal peptide. Neuropeptides. 1991;18:149–157. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(91)90107-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TUCKER J.F., BRAVE J.R., CHARALAMBOUS L., HOBBS A.J., GIBSON A. L-NG-nitro arginine inhibits non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic relaxations of guinea-pig isolated tracheal smooth muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1990;100:663–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDIN T.B., BONNER T.I., MEZEY E. Two receptors for vasoactive intestinal polypeptide with similar specificity and complementary distributions. Endocrinology. 1994;135:2662–2680. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.6.7988457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAGNER U., BREDENBRÖKER D., STORM B., TACKENBERG B., FEHMANN H.-C., VON WICHERT P. Effects of VIP and related peptides on airway mucus secretion from isolated rat trachea. Peptides. 1998;19:241–245. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(97)00257-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALTERS E.H., O'BYRNE P.M., FABBRI L.M., GRAF P.D., HOLTZMAN M.J., NADEL J.A. Control of neurotransmission by prostaglandins in canine trachealis smooth muscle. J. Appl. Pharmacol. 1984;57:129–133. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WARD J.K., BELVISI M.G., FOX A.J., MIURA M., TADJKARIMI S., YACOUB M.H., BARNES P.J. Modulation of cholinergic neural bronchoconstriction by endogenous nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal peptide in human airways in vitro. J. Clin. Invest. 1993;92:736–743. doi: 10.1172/JCI116644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEBBER S.E., WIDDICOME J.G. The effect of vasoactive intestinal peptide on smooth muscle tone and mucus secretion from the ferret trachea. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987;91:139–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb08992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WESSLER I., HELLWIG D., RACKE K. Epithelium-derived inhibition of [3H]acetylcholine release from the isolated guinea-pig trachea. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1990;342:387–393. doi: 10.1007/BF00169454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WESSLER I., KLEIN A., POHAN D., MACLAGAN J., RACKE K. Release of [3H]acetylcholine from the isolated rat or guinea-pig trachea evoked by preganglionic nerve stimulation; a comparison with transmural stimulation. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1991;344:403–411. doi: 10.1007/BF00172579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIDDICOMBE J.G. Neuroregulation of the nose and bronchi. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 1996;26 suppl. 3:32–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1996.tb00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]