Abstract

The inhibitory effects of nitric oxide (NO) on N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor function have been proposed to be mediated via the interaction of this gas with a redox-sensitive thiol moiety on the receptor. Here, we evaluated this suggested mechanism by examining the actions of various NO donors on native neuronal receptors as well as in wild-type and cysteine-mutated recombinant NMDA receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells.

The NO donor N-ethyl-2-(1-ethyl-2-hydroxy-2-nitrosohydraxino)ethanamine (NOC-12; 100 μM) produced a rapid and readily reversible inhibition of whole-cell currents induced by NMDA (30 μM) in cultured cortical neurons. The inhibition was apparent at all holding potentials, though a more pronounced block was observed at negative voltages. The effects of NOC-12 disappeared when the donor was allowed to expire. A similar receptor block was observed with another NO-releasing agent, S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP; 1 mM).

The blocking effects of NO released by SNAP, 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1; 1 mM), and 3-[2-hydroxy-1-(1-methylethyl)-2-nitrosohydrazino]-1-propanamine (NOC-5; 100 μM) on currents mediated by recombinant NR1/NR2B receptors were virtually indistinguishable from those observed on native receptors. Furthermore, mutating cysteines 744 and 798 of NR1, which constitute the principal redox modulatory site of the NR1/NR2B receptor configuration, did not affect the inhibition produced by NO.

The NR2A subunit may contribute its own redox-sensitive site. However, the effects of NO on NR1/NR2A receptors were very similar to those seen for all other receptor configurations evaluated. Hence, we conclude that NO does not exert its inhibition of NMDA-induced responses via a modification of any of the previously described redox-sensitive sites on the receptor.

Keywords: NMDA receptor, nitric oxide, redox modulatory site, cortical neurons, recombinant expression, patch-clamping

Introduction

Disulfide reducing agents can potentiate physiological responses mediated by the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor while thiol oxidants can reverse the effects of reductants and, in some instances, depress native responses (Tang & Aizenman, 1993a). Several redox-active substances of endogenous origin can modulate NMDA receptor function (Aizenman, 1994), and further, it has been observed that the redox state of the receptor can change without the addition of exogenous reductants or oxidants in vitro (Aizenman et al., 1989; Gozlan & Ben-Ari, 1995; Sinor et al., 1997). Hence, NMDA receptor function in the brain may be modulated by redox substances, thereby affecting the physiological and pathophysiological consequences of receptor activation. Indeed, substances known to oxidize the redox modulatory site in vitro have neuroprotective and anticonvulsive activity in vivo (Jensen et al., 1994; Quesada et al., 1997). It has been suggested that more than one redox-sensitive site may be present in a functional NMDA receptor (Sullivan et al., 1994; Köhr et al., 1994; Brimecombe et al., 1997; Arden et al., 1998; but see Paoletti et al., 1997). However, only one site has been unequivocally demonstrated to be formed by a pair of cysteines, cys-744 and cys-798, which are localized in an extracellular region between two transmembrane domains in the NR1 subunit (Sullivan et al., 1994).

Nitric oxide (NO), or a closely related derivative (Butler et al., 1995), has been shown to inhibit NMDA receptor-mediated physiological responses in a number of preparations (Hoyt et al., 1992; Manzoni et al., 1992; Lei et al., 1992; Fagni et al., 1995). Several mechanisms have been proposed to account for this inhibition, including voltage-dependent channel block (Fagni et al., 1995) and interference with down-stream calcium homeostatic processes (Hoyt et al., 1992). However, a widely-held view is that the gas can directly interact with the receptor's redox modulatory site (Lei et al., 1992), and specifically, with the one formed by cys-744 and cys-798 of NR1 (Stamler et al., 1997). This hypothesis is based partly on sequence homology to proposed targets for NO in other proteins (Stamler et al., 1997). The putative ensuing cysteine nitrosylation has been suggested to be responsible for the inhibition of the receptor-mediated responses (Lipton et al., 1993; Stamler et al., 1997). However, our group (Hoyt et al., 1992), as well as others (Fagni et al., 1995), previously suggested that the redox modulatory site does not, in fact, mediate any of the actions of NO at the NMDA receptor. In the present study, we re-examine the effects of NO in native, as well as in wild-type and cysteine mutated recombinant NMDA receptors in order to test directly the degree to which NO can modulate receptor function in the presence or absence of a functional redox site.

Methods

Tissue culture

All tissue culture reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), with the exception of iron-supplemented bovine calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT, U.S.A.), and minimal essential medium, (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, U.S.A.). Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO-K1; ATTC CCL61) were grown in Ham's F-12 nutrient medium with 10% foetal bovine serum and glutamine (1 mM) at 37°C in 5% CO2. These cells were passaged every 2 days at a 1 : 10 dilution for a maximum of 30 times. Cerebral cortices were dissociated from E-16 Sprague Dawley rats according to methods described previously (Hartnett et al., 1997). After dissociation, cells were plated at a density of 3–5×105 cells ml−1 in growth medium (v/v 80% Dulbecco's modified Eagle's minimum, 10% Ham's F12 nutrient mixture, 10% heat-inactivated iron-supplemented bovine calf serum, HEPES 25 mM, penicillin 24 U ml−1, streptomycin 24 mg ml−1 and L-glutamine 2 mM) into 35-mm tissue culture dishes containing 12-mm poly-L-lysine-coated glass coverslips. The cells were fed three times a week with growth medium. Non-neuronal cell proliferation was inhibited with cytosine arabinoside (2 mM) at 15 days in vitro after which the growth medium was changed to 2% serum and no F-12. Cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. Neurons were utilized for electrophysiological measurements between 25–29 days in vitro.

Transfection protocol

Generation of mammalian expression vectors for the NMDA receptor (NR) subunits (Boeckman & Aizenman, 1994, 1996) and green fluorescent protein (Brimecombe et al., 1997) have been previously described. The double mutant NR1 (C744A, C798A) plasmid was a kind gift from Dr S. Traynelis (Emory University, Atlanta, GA, U.S.A.). CHO cells were seeded at 3×105 cells well−1 in 6-well plates (35-mm wells) containing CHO media approximately 24 h prior to transfection. Serum-free CHO media (1 ml) containing 1.3 mg of total DNA and 6 ml of LipofectAMINE (Gibco-BRL) was added to each well. A ratio of 1 : 4.3 was used for GFP to total NR plasmid DNA, and a ratio of 1 : 3 was used for NR1 to NR2 subunits (Cik et al., 1993). After a 4 h incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 with the transfection solution, cells were re-fed with serum-containing CHO medium plus 300 μM ketamine (Boeckman & Aizenman, 1996). Recordings were performed approximately 2 days after transfection.

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings

Electrophysiological measurements were obtained from cortical neurons and transiently transfected CHO cells using the whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique. Methods for data acquisition and analysis have been previously described (Tang & Aizenman, 1993a). The extracellular recording solution consisted of (in mM) NaCl 150, KCl 2.8, CaCl2 1.0, HEPES 10 and 10 μM glycine (pH 7.2). For cortical neuron recordings, 0.25 μM tetrodotoxin (CalBiochem, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.) was also added to this solution. Patch electrodes (2 MΩ) were filled with (in mM) CsF 140, EGTA 10, CaCl2 1, and HEPES 10 (pH 7.2). Drugs were applied onto cells by a multi-barrel fast perfusion system (Warner Instrument Corp., Hamden, CT, U.S.A.). Freshly-prepared stock solutions of 3-[2-Hydroxy-1-(1-methylethyl)-2-nitrosohydrazino]-1-propanamine (NOC-5; CalBiochem) and N-ethyl -2-(1-ethyl-2-hydroxy-2-nitrosohydraxino) ethanamine (NOC-12; CalBiochem) were made in NaOH (10 mM), diluted in external recording solution and used immediately. 3-Morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1; BIOMOL, Plymouth Meeting, PA, U.S.A.) and S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP; BIOMOL) were dissolved directly in external recording solution and used immediately. When necessary, NO was allowed to expire by allowing the NO donor-containing solution to be in direct contact with air and exposed to light overnight.

Results

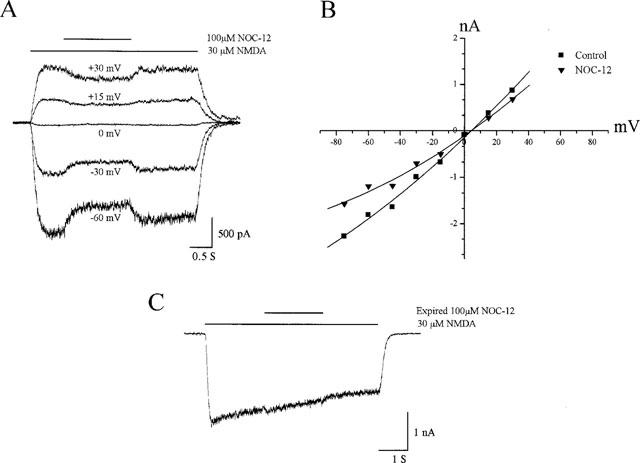

Whole-cell currents were obtained from cortical neurons during the application of NMDA (30 μM) alone or in the presence of freshly prepared NOC-12 (100 μM) at several holding potentials. The half-life of NO release by this compound is 327 min at 22°C in physiological solutions, according to the supplier (CalBiochem). We observed that inclusion of the NO donor produced a readily reversible inhibition of the NMDA-induced responses at all holding voltages tested (Figure 1A); Current-voltage relationships were generated by measuring the steady state current amplitude in the absence or presence of NOC-12 (Figure 1B); a more pronounced block was apparent at negative membrane potentials when compared to positive voltages. The block at −60 mV for this drug was near 25% (n=5; Table 1). In a separate group of neurons (n=6), we tested for the ability of expired NOC-12 to block the NMDA receptor-mediated responses. As is evident from Figure 1C, the spent donor did not influence the currents to any measurable extent. These results corroborate the previously noted actions of other NO donors such as SIN-1, SNAP and isosorbide dinitrate which demonstrate that the gas can reversibly block the NMDA receptor in both a voltage-dependent and voltage-independent manner, and that the use of NO-expired donors, or NO scavengers such as haemoglobin, can prevent the actions of the gas on the responses mediated by this receptor (Fagni et al., 1995). Similar NMDA receptor inhibition was observed in the present investigation with the use of another NO donor, SNAP (1 mM; n=5), on a separate group of cortical neurons (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of NMDA-activated currents by NO in neurons. (A) Representative whole-cell current traces obtained at −60, −30, 0, +15 and +30 mV in rat cortical neurons in culture during activation by NMDA (30 μM) in the absence and presence of freshly-prepared NOC-12 (100 μM). (B) Current-voltage relationship of steady-state NMDA responses in the absence and presence of NOC-12 for the same cell shown in A. (C) Whole-cell current trace during activation by NMDA at −60 mV in the absence and presence of NOC-12 (100 μM) which had been allowed to expire overnight.

Table 1.

Comparison of the NO-mediated block of whole-cell NMDA currents (−60 mV)*

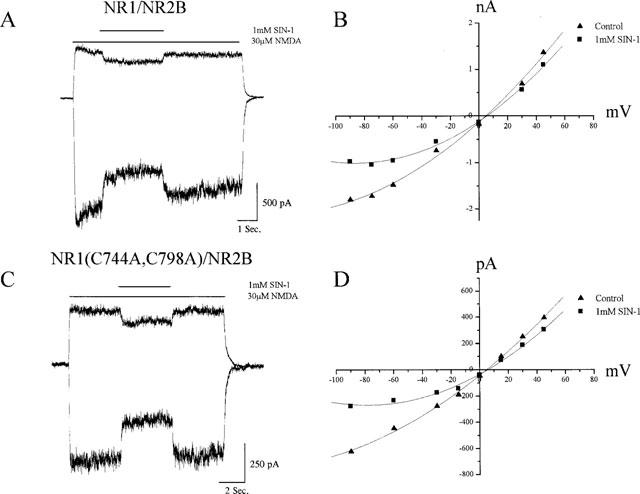

We next turned our attention to the effects of NO on NMDA-induced responses mediated by recombinant receptors. We chose first to utilize the NR1/NR2B receptor configuration as cys-744 and cys-798 of NR1 constitute the principal redox-sensitive site of this subunit combination (Sullivan et al., 1994). As seen with native receptors in neurons, NO, released by the donors NOC-5 (100 μM; n=3), SIN-1 (1 mM; n=6), and SNAP (1 mM; n=4), produced similar block of the whole cell currents mediated by this receptor configuration (Table 1). The half-life of NO release by NOC-5 is only 93 min (CalBiochem) and thus may transiently produce a higher concentration of the gas than a comparable amount of another donor. This likely accounts for the slightly greater degree block observed with this donor (Table 1). Figure 2A shows the typical current block observed with the NO donor SIN-1. The current-voltage relationship obtained from NR1/NR2B receptor-mediated responses (Figure 2B) demonstrate that the voltage-dependence of the inhibition is similar to what was observed with native neuronal receptors. Although SIN-1 also produces superoxide anions, a previous investigation reported that the effects of this donor on NMDA receptor-mediated currents are not affected by the addition of superoxide dismutase and catalase (Fagni et al., 1995). A separate set of CHO cells were then transfected with the double mutant NR1(C744A, C798A) together with NR2B. In these, the pattern NMDA response inhibition produced by the NO donors SIN-1 (Figure 2B,C; n=5) and SNAP (n=4) was virtually indistinguishable to that seen in the wild-type receptors and native channels (Table 1). Thus, the presence or absence of the redox site on NR1 had no influence on the actions of NO on NR2B-containing receptors.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of NMDA-activated currents by NO in transfected CHO cells does not require the presence of a functional redox site. (A) Representative whole-cell currents obtained at −60 and +30 mV in a CHO cell expressing NR1/NR2B receptors during application of NMDA (30 μM) in the absence and presence of SIN-1 (1 mM). (B) Current-voltage relationship of steady-state NMDA responses in the absence and presence of NOC-12 for the same cell shown in A. (C) Representative whole-cell currents obtained in a CHO cell expressing NR1 (C744A, C798A)/NR2B receptors, which lack a functional redox site, during application of NMDA with or without SIN-1. (D) Current-voltage relationship of steady-state NMDA responses in the absence and presence of NOC-12 for the same cell shown in C.

The redox sensitivity of NR1/NR2A receptors is not critically dependent on cys-744 and cys-798 of NR1 (Sullivan et al., 1994; Arden et al., 1998). Although individual thiol-reactive residues in NR2A have not yet been localized (Köhr et al., 1994), results of a recent study from our laboratory suggest that this subunit does indeed have unique redox attributes (Arden et al., 1998). However, the effects of both SIN-1 (n=8) and SNAP (n=4) on this subunit configuration were almost identical to those seen in neuronal receptors and in wild-type and cysteine mutated NR1/NR2B receptors (Table 1). This suggests that the NO inhibition of NMDA receptor currents is not subunit dependent.

Discussion

Cysteine residues 744 and 798 on NR1 appear to constitute the principal redox modulatory site of receptors composed of this subunit when it is co-expressed with either NR2B, NR2C or NR2D (Sullivan et al., 1994). Receptors which are assembled with NR1 and NR2A contain a second redox sensitive site which has yet to be localized at the molecular level (Köhr et al., 1994; Arden et al., 1998). Our present results suggest that NO does not interact with the redox modulatory site formed by cys-744 and cys-798 of NR1. In fact, given the almost identical effects of NO on native receptors and on recombinant receptors composed of either NR1/NR2A or NR1/NR2B, it is unlikely that the gas interacts with any of the previously investigated sites on the NMDA receptor which are sensitive to redox reagents. This is in direct contrast to the widely accepted mechanism of NO inhibition of NMDA receptors that has been suggested by other investigators (Lei et al., 1992; Lipton et al., 1993; Stamler et al., 1997).

Our conclusion, however, is not altogether surprising as the actions of NO on the NMDA receptor do not seem to fit the pattern of effects seen for other agents known to interact with the redox site. For instance, the inhibitory effects of thiol oxidants on the NMDA receptor do not spontaneously reverse (Aizenman et al., 1989; Tang & Aizenman, 1993a). That is, a subsequent treatment with a disulfide reducing agent is necessary to reverse the effects of oxidants. In contrast, as seen in this and prior studies (Hoyt et al., 1992; Manzoni et al., 1992; Lei et al., 1992; Fagni et al., 1995), the effects of NO appear to be readily and spontaneously reversible. Inhibition by NO is also present even after prior oxidation of the receptor with a thiol agent (Hoyt et al., 1992). Additionally, previous studies have shown that after chemical alkylation and subsequent functional elimination of the redox site in neurons (Tang & Aizenman, 1993a), the inhibitory effects of NO remain virtually intact (Hoyt et al., 1992; Fagni et al., 1995). Finally, redox agents do not alter the conductance of native or recombinant single NMDA receptor channels (Tang & Aizenman, 1993a; Brimecombe et al., 1997), while one of the principal reported actions of NO on unitary currents is to decrease their amplitude (Fagni et al., 1995).

Lei et al. (1992) first suggested that NO could interact with the redox modulatory site of the NMDA receptor. This group reported that NO donors could depress NMDA receptor-mediated responses in neurons in a partially reversible manner. This reversibility, inconsistent with an effect at the redox site, was attributed to a rapid decomposition of putative S-nitrosothiol groups formed by the interaction of NO with the cysteine moieties that formed this site. However, these investigators also noted that NO could reversibly depress responses even after exposure of the receptor to thiol oxidants, which would eliminate any available free thiols for NO to nitrosylate. Lei and co-workers argued that NO may have reacted with thiols spared by the oxidants. However, this argument is not consistent with the fact that (i) oxidants depress NMDA-induced responses by interacting with the redox site, and (ii) this inhibitory actions of thiol oxidants have been shown to be completely abolished following alkylation of the receptor (Tang & Aizenman, 1993a,1993b; Aizenman et al., 1994). As mentioned earlier, in our previous studies (Hoyt et al., 1992) as well as in those of others (Fagni et al., 1995), it was observed that alkylation did not alter, to any extent, the inhibitory effects of NO. Indeed, a close look at the data presented by Lei et al. (1992) reveal that the effects of NO in depressing whole-cell currents before (38%) and after (26%) treatment with an alkylating agent are not dramatically different. Hence, we must conclude that the inhibitory effects of NO on NMDA receptor function appear not to be determined by the subunit composition of the receptor, nor by the presence or absence of the redox site on NR1. The present findings refute the hypothesis that cys-744 and cys-798 on the NR1 subunit are the target of NO (Stamler et al., 1997), at least with respect to the functional inhibition of the channel.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs S. Nakanishi, P. Seeburg, S. Traynelis, and M. Chalfie for the NR and GFP plasmids; Dr P.A. Rosenberg for valuable input, and K. Hartnett for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grant NS29365.

Abbreviations

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- cys

cysteine

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOC-5

3-[2-hydroxy-1-(1-methylethyl)-2-nitrosohydrazino]-1-propanamine

- NOC-12

N-ethyl-2-(1-ethyl-2-hydroxy-2-nitrosohydraxino)ethanamine

- NR

NMDA receptor

- SIN-1

3-morpholinosydnonimine

- SNAP

S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine

References

- AIZENMAN E.Redox modulation of the NMDA receptor Direct and allosteric control of glutamate receptors 1994Boca Raton, FL, U.S.A.: CRC Press; 95–104.eds. Palfreyman, M.G., Reynolds, I.J. & Skolnik, P., pp [Google Scholar]

- AIZENMAN E., JENSEN F.E., GALLOP P.M., ROSENBERG P.A., TANG L.H. Further evidence that pyrroloquinoline quinone interacts with the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor redox site in rat cortical neurons in vitro. Neurosci. Letts. 1994;168:189–192. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AIZENMAN E., LIPTON S.A., LORING R.H. Selective modulation of NMDA responses by reduction and oxidation. Neuron. 1989;2:1257–1263. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARDEN S.R., SINOR J.D., POTTHOFF W.K., AIZENMAN E. Subunit-specific interactions of cyanide with the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., U.S.A. 1998;273:21505–21511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOECKMAN F.A., AIZENMAN E. Stable transfection of the NR1 subunit in Chinese hamster ovary cells fails to produce a functional N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. Neurosci. Lett. 1994;173:189–192. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOECKMAN F.A., AIZENMAN E. Pharmacological properties of acquired excitotoxicity in Chinese hamster ovary cells transfected with N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therap. 1996;279:515–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRIMECOMBE J.C., BOECKMAN F.A., AIZENMAN E. Functional consequences of NR2 subunit composition in single recombinant N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:11019–11024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.11019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUTLER A.R., FLITNEY F.W., WILLIAMS D.L. NO, nitrosonium ions, nitroxide ions, nitrosothiols and iron-nitrosyls in biology: a chemist's perspective. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1995;16:18–22. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)88968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIK M., CHAZOT P.L., STEPHENSON F.A. Optimal expression of cloned NMDAR1/NMDAR2A Heteromeric glutamate receptors: A biochemical characterization. J. Biochem. 1993;296:877–883. doi: 10.1042/bj2960877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAGNI L., OLIVIER M., LAFON-CAZAL M., BOCKAERT J. Involvement of divalent ions in the nitric oxide-induced blockade of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in cerebellar granule cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;47:1239–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOZLAN H., BEN-ARI Y. NMDA receptor redox sites: are they targets for selective neuronal protection. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1995;16:368–374. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARTNETT K.A., STOUT A.K., RAJDEV S., ROSENBERG P.A., REYNOLDS I.J., AIZENMAN E. NMDA receptor-mediated neurotoxicity: a paradoxical requirement for extracellular Mg2+ in Na+/Ca2+-free solutions in rat cortical neurons in vitro. J. Neurochem. 1997;68:1836–1845. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68051836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOYT K.R., TANG L.H., AIZENMAN E., REYNOLDS I.J. Nitric oxide modulates NMDA-induced increases in intracellular Ca2+ in cultured rat forebrain neurons. Brain Res. 1992;592:310–316. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91690-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JENSEN F.E., GARDNER G.J., WILLIAMS A.P., GALLOP P.M., AIZENMAN, ROSENBERG P.A. The putative essential nutrient pyrroloquinoline quinone is neuroprotective in a rodent model of hypoxic/ischemic brain injury. Neurosci. 1994;62:399–406. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KÖHR G., ECKARDT S., LUDDENS H., MONYER H., SEEBURG P.H. NMDA receptor channels: subunit-specific potentiation by reducing agents. Neuron. 1994;12:1031–1040. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEI S.Z., PAN Z.H., AGGARWAL S.K., CHEN H.S., HARTMAN J., SUCHER N.J., LIPTON S.A. Effect of nitric oxide production on the redox modulatory site of the NMDA receptor-channel complex. Neuron. 1992;8:1087–1099. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIPTON S.A., CHOI Y.B., PAN Z.H., LEI S.Z., CHEN H.S., SUCHER N.J., LOSCALZO J., SINGEL D.J., STAMLER J.S. A redox-based mechanism for the neuroprotective and neurodestructive effects of nitric oxide and related nitroso-compounds. Nature. 1993;364:626–632. doi: 10.1038/364626a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANZONI O., PREZEAU L., MARIN P., DESHAGER S., BOCKAERT J., FAGNI L. Nitric oxide-induced blockade of NMDA receptors. Neuron. 1992;8:653–662. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90087-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAOLETTI P., ASCHER P., NEYTON J. High-affinity zinc inhibition of NMDA NR1-NR2A receptors. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:5711–5725. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05711.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUESADA O., HIRSCH J.C., GOZLAN H., BEN-ARI Y., BERNARD C. Epileptiform activity but not synaptic plasticity is blocked by oxidation of NMDA receptors in a chronic model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 1997;26:373–380. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(96)01004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINOR J.D., BOECKMAN F.A., AIZENMAN E. Intrinsic redox properties of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor can determine the developmental expression of excitotoxicity in rat cortical neurons in vitro. Brain Res. 1997;747:297–303. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STAMLER J.S., TOONE E.J., LIPTON S.A., SUCHER N.J. (S)NO signals: translocation, regulation, and a consensus motif. Neuron. 1997;18:691–696. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80310-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SULLIVAN J.M., TRAYNELIS S.F., CHEN H.S., ESCOBAR W., HEINEMANN S.F., LIPTON S.A. Identification of two cysteine residues that are required for redox modulation of the NMDA subtype of glutamate receptor. Neuron. 1994;13:929–936. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANG L.H., AIZENMAN E. The modulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors by redox and alkylating reagents in rat cortical neurones in vitro. J. Physiol. 1993a;465:303–323. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANG L.H., AIZENMAN E. Allosteric modulation of the NMDA receptor by dihydrolipoic and lipoic acid in rat cortical neurons in vitro. Neuron. 1993b;11:857–863. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]