Abstract

The present work examined the effects of the subtype 2 of angiotensin II (AT2) receptors on the pressure-natriuresis using a new peptide agonist, and the possible involvement of cyclic guanosine 3′, 5′ monophosphate (cyclic GMP) in these effects.

In adult anaesthetized rats (Inactin, 100 mg kg−1, i.p.) deprived of endogenous angiotensin II by angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition (quinapril, 10 mg kg−1, i.v.), T2-(Ang II 4-8)2 (TA), a highly specific AT2 receptor agonist (5, 10 and 30 μg kg−1 min−1, i.v.) or its solvent was infused in four groups. Renal functions were studied at renal perfusion pressures (RPP) of 90, 110 and 130 mmHg and urinary cyclic GMP excretion when RPP was at 130 mmHg. The effects of TA (10 μg kg−1 min−1) were reassessed in animals pretreated with PD 123319 (PD, 50 μg kg−1 min−1, i.v.), an AT2 receptor antagonist and the action of the same dose of PD alone was also determined.

Increases in RPP from 90 to 130 mmHg did not change renal blood flow (RBF) but induced 8 and 15 fold increases in urinary flow and sodium excretion respectively. The 5 μg kg−1 min−1 dose of TA was devoid of action. The 10 and 30 μg kg−1 min−1 doses did not alter total RBF and glomerular filtration rate, but blunted pressure-diuresis and natriuresis relationships. These effects were abolished by PD.

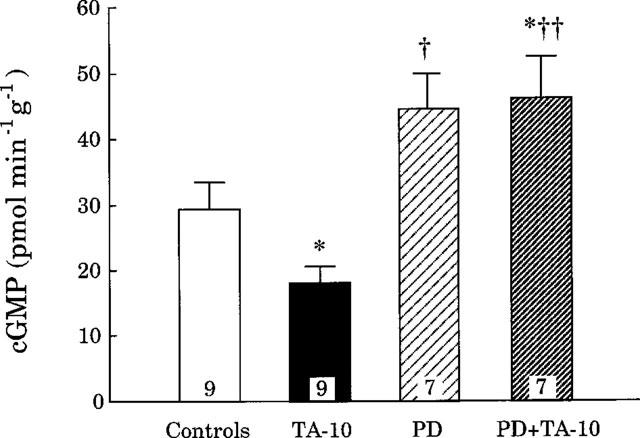

TA decreased urinary cyclic GMP excretion. After pretreatment with PD, this decrease was reversed to an increase which was also observed in animals receiving PD alone.

In conclusion, renal AT2 receptors oppose the sodium and water excretion induced by acute increases in blood pressure and this action cannot be directly explained by changes in cyclic GMP.

Keywords: Angiotensin II, AT2 receptors, cyclic GMP, pressure-natriuresis

Introduction

At the renal level, angiotensin II (AII) exerts potent vasoconstrictor effects and enhances the tubular sodium reabsorption, thus lowering the pressure-natriuresis (Mattson et al., 1991; Van Der Mark & Kline, 1994) which is a major determinant of the long-term blood pressure level (Guyton, 1990). Most of the renal actions of AII are mediated through subtype 1 receptors (AT1). The role of the receptors belonging to the subtype 2 (AT2) remains poorly defined. In the whole organism, mice lacking the AT2 receptor gene exhibit increases in the blood pressure response to AII (Hein et al., 1995; Ichiki et al., 1995) thus suggesting that AT2 receptors oppose the AT1-mediated vasoconstriction. In the kidneys where AT2 receptors represent 5–10% of the total AII receptors (Chang & Lotti, 1991; Zhuo et al., 1992; 1993; Ozono et al., 1997), the reported vascular effects are controversial. PD 123319, an AT2 receptor antagonist was found to block the AII-induced renal vasoconstriction (Chatziantoniou & Arendshorst, 1993) and intracellular calcium mobilization in vascular smooth muscle cells (Zhu & Arendshorst, 1996). In contrast, other studies showed that PD 123319 augmented the AII-induced vasoconstriction in both pre- and post-glomerular arterioles (Arima et al., 1996; Endo et al., 1997). Concerning the excretory functions, AT2 receptor blockade with PD 123319 increased the urine volume, chloride and bicarbonate excretion in anaesthetized rats (Cogan et al., 1991) and increased free water formation in anaesthetized dogs (Keiser et al., 1992). We previously observed that, in rats infused with AII and the AT1 receptor antagonist losartan, the blockade of AT2 receptors with PD 123319 increased the pressure-natriuresis while CGP 42112B, an AT2 receptor ligand with agonistic properties, lowered the pressure-natriuresis (Lo et al., 1995). Since the interpretation of the above reported data relies upon the selectivity of the various ligands, our attention was drawn by a new compound T2-(Ang II 4-8)2 (TA), which is the most specific peptide agonist available for AT2 receptors (Grouzmann et al., 1995). We therefore thought it is of interest to examine its effects on the pressure-natriuresis. In addition, since it has been suggested that AT2 receptors may interact with the formation of cyclic guanosine 3′, 5′ monophosphate (cyclic GMP) which mediates the renal vasodilatation and natriuresis induced by nitric oxide (NO) (Siragy et al., 1992) and atrial natriuretic peptide (Margulies & Burnett, 1994), we measured urinary excretion of cyclic GMP so as to approach the intracellular mechanisms of the effects of AT2 receptor stimulation.

Methods

Animals

Ten week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats (Iffa-Credo, Les Oncins, France) were used. They were housed in controlled conditions (temperature: 21±1°C; humidity: 60±10%; lighting: 8–20 h), and fed a standard rat chow containing 0.3% sodium (Elevage UAR, Villemoisson sur Orge, France) and tap water ad libitum. The studies were conducted in agreement with our institutional guidelines for animal care.

AT2 receptor ligands

TA (T2-(Ang II 4–8)2) is a template-assembled peptide agonist for AT2 receptors (Institute of Organic Chemistry, Lausanne, Switzerland). It is made of two angiotensin II 4–8 pentapeptide fragments (Ang II 4–8)2, attached to a carrier molecule (T2) which alone did not bind to either AT1 or AT2 receptors (Grouzmann et al., 1995). Binding assays showed that in the presence of an AT1 antagonist, TA completely inhibited the specific binding of 125I-AII to the AT2 receptors of a rat adrenal membrane preparation and that half-maximal inhibition (IC50) occurred at the concentration of 2×10−7 M. In contrast, TA at the concentration of 10−5 M did not bind to AT1 receptors of rat aortic smooth muscle cells (Grouzmann et al., 1995). PD 123319 (Parke-Davis, Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A.), a non-peptide AT2 receptor antagonist, exhibits an IC50 of 0.5×10−7 M for AT2 receptors and did not bind to AT1 receptors of rat aortic smooth muscle cells at the concentration of 10−5 M (Grouzmann et al., 1995). PD 123319 was dissolved in saline and infused at the dose of 50 μg kg−1 min−1 which, according to Macari et al. (1993), yields plasma concentrations close to 3×10−6 M, i.e. a value which remains highly specific for AT2 receptors. TA was dissolved in a 12% solution of dimethyl sulphoxide in saline and three doses (5, 10 and 30 μg kg−1 min−1, i.v.) were chosen according to preliminary experiments.

Surgical preparation

Pressure-natriuresis was studied using the method of Roman & Cowley (1985). The right kidney and adrenal gland were removed and the rats allowed 7–10 days to recover. On the day of experiment, the rats were anaesthetized with Inactin (100 mg kg−1, i.p., Research Biochemicals, Natick, MA, U.S.A.) and placed on a heating blanket (Model 50-6980, Harvard Apparatus, Edenbrige, KY, U.S.A.) to maintain the rectal temperature at 37±0.5°C. After tracheotomy, the left jugular vein was cannulated for infusion. Catheters were placed into the left carotid and femoral arteries to sample blood and to record the mean arterial blood pressure through a pressure transducer (Model P23ID, Statham Instrument Division, Gould Inc., Cleveland, OH, U.S.A.). After an abdominal incision, the left kidney was exposed and denervated by stripping all the visible renal nerves and coating the renal artery with a 10% solution of phenol in ethanol. The remaining adrenal gland was then removed and the left ureter cannulated for urine collection. Two adjustable silastic balloon cuffs were placed around the aorta, one above the renal artery between the superior mesenteric and celiac arteries, the other below the left renal artery so that the renal perfusion pressure (RPP) could be fixed at different levels. Silk ligatures were placed loosely around the superior mesenteric and celiac arteries and tighten to further elevate the RPP. An ultrasonic flow probe (1RB) was placed around the left renal artery so as to continuously record the total renal blood flow using a transonic transit-time flowmeter (Model T106, Transonic Systems Inc., Ithaca, NY, U.S.A.). After a priming dose (250 mg kg−1, i.v.) of polyfructosan (Inutest, Laevosan, Linz, Austria), a hormone-cocktail (Mattson et al., 1991; Liu et al., 1996) designed to fix the circulating levels of the most important sodium- and water-retaining hormones was infused at a rate of 330 μl kg−1 min−1 (Pump Model 2400-001, Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA, U.S.A.). It contained d-aldosterone (66 ng kg−1 min−1), hydrocortisone (33 ng kg−1 min−1), norepinephrine (333 ng kg−1 min−1) and Arg8-vasopressin acetate (0.17 ng kg−1 min−1). Drugs were obtained from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) and dissolved in 0.9% sodium chloride containing 1% bovine serum albumin (Fraction V) and 1.25% polyfructosan. At the end of the experiment, the left kidney was decapsulated, removed, cut in half, blotted dry and weighed.

Renal parameters

RPP (mmHg) was estimated as the mean femoral artery pressure when the suprarenal aortic cuff was inflated and as the mean carotid artery pressure when the infrarenal aortic cuff was inflated. Glomerular filtration rate (ml min−1 g−1) was measured by polyfructosan clearance. Urine flow (μl min−1 g−1) was determined by weighing, and sodium concentration by flame photometry (IL meter, model 243, Lexington, MA, U.S.A.) so as to calculate urinary sodium excretion (μmoles min−1 g−1). Urinary concentration of cyclic GMP was determined by an enzyme immunoassay kit (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A.) (Pradelles et al., 1989) with which the minimum detectable concentration approched 0.04 pmol ml−1 and the coefficient of variation was below 5%. All the parameters were normalized per gram of the left kidney weight.

Experimental protocol

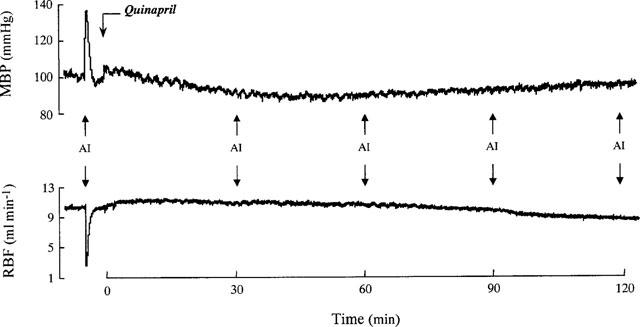

The endogenous production of AII was blocked by an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, quinapril (10 mg kg−1, i.v.) (Parke-Davis, Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A.) so as to eliminate any interference due to changes in renal renin release. The efficiency of this inhibition during the whole of the experimental period is shown in Figure 1. The injection of angiotensin I (AI, 750 ng kg−1) in five animals increased mean blood pressure by 37±5% and lowered renal blood flow by 82±5%. These responses were fully abolished during the 2 h following quinapril injection.

Figure 1.

Averaged values (n=5) of mean blood pressure (MBP) and renal blood flow (RBF) in response to angiotensin I (AI) injections (750 ng kg−1) before, 30, 60, 90 and 120 min after angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition by quinapril (10 mg kg−1).

Sixty minutes after the hormonal-cocktail infusion begun, quinapril (10 mg kg−1, i.v.) was given 30 min prior to the start of the study. In a first protocol, four groups of animals were used. Controls received dimethyl sulphoxide (the solvent for TA) at the rate corresponding to that infused with the different doses of TA. Three doses of TA (5, 10 and 30 μg kg−1 min−1, i.v) were randomly allocated each to one group of rats 10 min prior to the start of the study. To confirm the specificity of the findings, TA (10 μg kg−1 min−1) was given to another group of animals in which PD 123319 (50 μg kg−1 min−1) was infused starting 15 min before. Finally, so as to check whether PD 123319 by itself could influence renal functions, an additional group of rats received PD 123319 alone at the same dose of 50 μg kg−1 min−1. In both protocols, the renal functions were studied at a RPP of 90 mmHg, a level close to the basal mean blood pressure level, and, later on, at 110 and 130 mmHg. Urines were collected for 20, 10 and 10 min respectively. Arterial blood (200 μl) was sampled at the end of each period. Urines collected at RPP of 130 mmHg were used for cyclic GMP assay, since at the lower levels of pressure the volume of urines did not allow all the measurements to be done.

Statistical analysis

Values are means±s.e.mean. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to statistically evaluate the differences between groups over the whole range of RPP. The differences at a given level of RPP were assessed using the Student's t-test for unpaired data. A difference was considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

Results

Effects of AT2 receptor ligands on renal functions

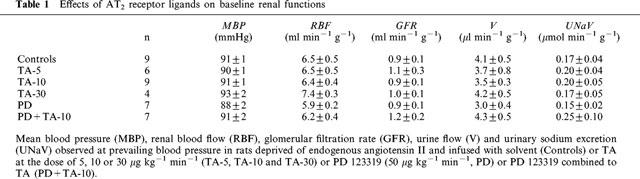

The renal functions observed at a RPP of 90 mmHg, a level close to the basal mean blood pressure level in rats deprived of endogenous AII are shown in Table 1. Neither the infusion of TA nor that of PD 123319 changed significantly these baseline renal functions.

Table 1.

Effects of AT2 receptor ligands on baseline renal functions

Figure 2 shows that in control animals, a stepwise elevation in RPP from 90 to 130 mmHg, did not change total renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate, but induced 8 and 15 fold increases in urine flow and sodium excretion respectively. The lowest dose of TA (5 μg kg−1 min−1) did not modify the effects of increasing renal perfusion pressure. When infused at the rate of 10 μg kg−1 min−1, TA did not affect, over the whole range of pressures, total renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate, while it significantly decreased pressure-diuresis (ANOVA, P<0.001) and natriuresis relationships (ANOVA, P<0.03) by increasing the tubular sodium reabsorption (98.0±0.2 and 99.0±0.3% in control and TA-treated animals respectively at the RPP of 130 mmHg, P<0.05). The 30 μg kg−1 min−1 dose of TA induced effects similar to those of 10 μg kg−1 min−1.

Figure 2.

Effects of TA on the relationships between renal perfusion pressure (RPP), renal blood flow (RBF), glomerular filtration rate (GFR), urine flow (V) and sodium excretion (UNaV) in rats deprived of endogenous angiotensin II and infused with solvent (Controls) or TA at the doses of 5, 10 or 30 μg kg−1 min−1 (TA-5, TA-10 and TA-30).

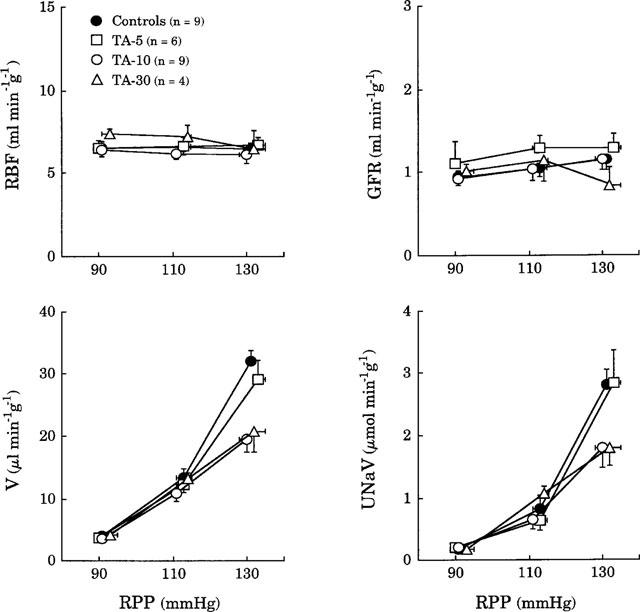

Figure 3 shows that, in animals deprived of endogenous AII, pressure-diuresis and natriuresis observed during the infusion of PD 123319 alone did not differ from those of controls although glomerular filtration rate was significantly increased (ANOVA, P<0.01). The combined infusion of PD 123319 and TA did not change the relationships between RPP, renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate. The decreases in pressure-diuresis and -natriuresis observed during infusion of TA (10 μg kg−1 min−1) were fully abolished by PD 123319.

Figure 3.

Effects of renal perfusion pressure (RPP) on renal blood flow (RBF), glomerular filtration rate (GFR), urine flow (V) and sodium excretion (UNaV) in rats deprived of endogenous angiotensin II and infused with solvent (Controls) or TA (10 μg kg−1 min−1, TA-10) or PD 123319 (50 μg kg−1 min−1, PD) or PD 123319 combined to TA (PD+TA-10).

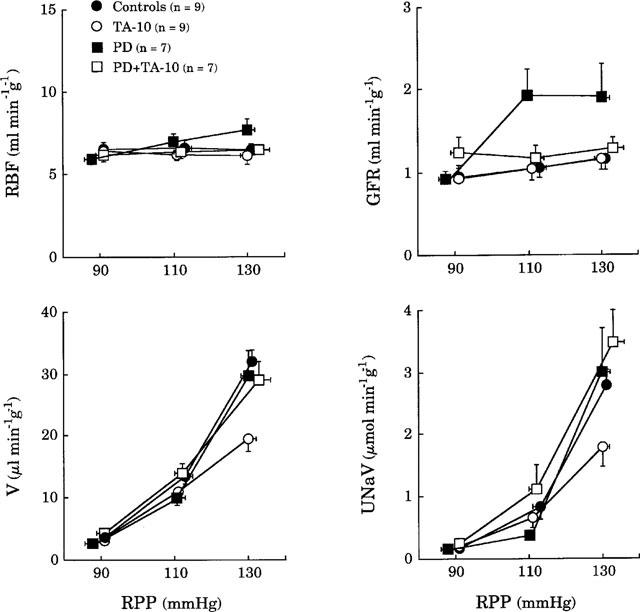

Effect of AT2 receptor stimulation on urinary excretion of cyclic GMP

As shown in Figure 4, urinary excretion of cyclic GMP, measured at the renal perfusion pressure of 130 mmHg, was significantly decreased during the infusion of TA alone (10 μg kg−1 min−1). This decrease was transformed into an increase when TA was given in rats pretreated with PD 123319. Interestingly, PD 123319 alone also tended to increase the urinary excretion of cyclic GMP.

Figure 4.

Urinary excretion of cyclic guanosine 3′, 5′ monophosphate (cyclic GMP) in rats deprived of endogenous angiotensin II and infused with solvent (Controls) or TA (10 μg kg−1 min−1, TA-10) or PD 123319 (50 μg kg−1 min−1, PD) or PD 123319 combined to TA (PD+TA-10). The renal perfusion pressure was set at 130 mmHg. *P<0.05 vs controls; †P<0.05, ††P<0.01 vs TA-10.

Discussion

The present work shows that the acute stimulation of AT2 receptors with a new highly specific peptide agonist in adult rats, blunts pressure-natriuresis and -diuresis, and suggests that these effects of AT2 receptors do not directly involve changes in cyclic GMP release.

The method developed by Roman & Cowley (1985) is one of the most widely used to study the acute pressure-natriuresis in anaesthetized rats. We applied this technique after ACE inhibition so as to block the endogenous production of AII and possibly enhance the renal sensitivity to AII (Richer et al., 1983). The efficiency of ACE inhibition in this work was demonstrated by the lack of pressor response to AI injections during the whole experimental period. Among the compounds having agonistic properties for AT2 receptors, TA seems the most selective as it leaves intact AT1 receptors at concentration above 10−5 M, while CGP 42112, starts having significant interactions with AT1 receptors at the concentration of 10−6 M (Grouzmann et al., 1995). Using this compound, we observed that at the doses of 5, 10 and 30 μg kg−1 min−1, TA had no effect on the total renal blood flow. Since this latter is mainly controlled by AT1 receptors (Keiser et al., 1992; Lo et al., 1995), this result suggests that even the highest dose of TA used, remained fully specific for AT2 receptors. Contrasting with this lack of overall vascular effect, TA lowered pressure-natriuresis and -diuresis. These effects were dose-dependent partially only since, the 5 μg kg−1 min−1 dose was devoid of action while the maximum effect was obtained with the 10 μg kg−1 min−1 dose. Such a narrow dose-response relationship is difficult to explain. It might relate to the low number of AT2 receptors available or to the high sensitivity of AT2 receptors in our experimental conditions. The specificity of the observed effects of TA on natriuresis and diuresis was further confirmed by their disappearance after infusion of PD 123319 at a dose which does not affect AT1 receptors (Macari et al., 1993). Thus AT2 receptor stimulation lowers pressure-natriuresis. According to this finding, Madrid et al., (1997a) recently reported that in rats in which NO synthesis was blocked with Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester, AT1 receptor blockade had no effect on the slope of the pressure-natriuresis curve, while PD 123319 normalized it thus indicating that the pressure-natriuresis was under the control of AT2 receptors. Such a function of AT2 receptors is also in accordance with the fact that in acute conditions, AII lowers the pressure-natriuresis (Mattson et al., 1991) while AT1 receptor blockade with losartan given acutely does not affect the pressure-natriuresis in rats (Kline & Liu, 1994; Lo et al., 1995). In addition, recent studies showing that dietary sodium depletion increases the density of AT2 receptors in adult rat kidneys (Ozono et al., 1997) and decreases that of AT1 receptors (Ruan et al., 1997) reinforce the hypothesis that AT2 receptors could be involved in sodium preservation. In that respect, since in the present experiment, as well as in our previous one (Lo et al., 1995), the effects of AT2 receptor stimulation or blockade were more marked when renal perfusion pressure was elevated, it can be speculated that AT2 receptors contribute to prevent the sodium losses which would follow acute increases in blood pressure.

The mechanisms of this action are difficult to approach, because little is known about not only the intracellular signaling pathways of AT2 receptors but also about the mechanisms involved in pressure-natriuresis. Concerning the signaling pathways of AT2 receptors in vitro studies conducted in tissues that selectively or mainly express these receptors, show that the activation of AT2 receptors in R3T3 fibroblasts stimulates a phosphotyrosine phosphatase (Tsuzuki et al., 1996) and decreases cyclic GMP formation in rat adrenal gland (Israel et al., 1995). More recently, several kinases belonging to transduction cascades were shown to be altered by AT2 receptor stimulation (Fischer et al., 1998). Concerning the mechanisms involved in pressure-natriuresis, the most widely accepted hypothesis is that, in rats, they implicate increases in the poorly regulated papillary blood perfusion (Roman et al., 1988a) leading to rises in renal interstitial pressure (Granger, 1992) which will reduce the tubular sodium and fluid reabsorption. In that respect, the reported effects of AII on renal medullary circulation varied upon the experimental conditions. The intravenous infusion of AII at high doses did not modify (Nobes et al., 1991) or increased (Parekh & Zou, 1996) medullary blood flow, an effect which was mediated by the release of vasodilator prostaglandins. The intrarenal infusion of AII at a physiological dose (0.5 ng kg−1 min−1) decreased papillary flow without altering cortical renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (Faubert et al., 1987). Consistently, AII receptor blockade with saralasin as well ACE inhibition increased papillary blood flow in rats having received a bradykinin antagonist (Roman et al., 1988b). Since AT1 receptor blockade was found devoid of action on papillary blood flow (Madrid et al., 1997b), it can be postulated that AII constricts medullary vessels through AT2 receptors. Another possible mechanism is that AT2 receptor stimulation might blunt NO release. This is suggested by the fact that, in the present work, as well as in our previous one (Lo et al., 1995), AT2 receptors were found more efficient at high than at normal pressure, a condition which, through elevated shear-stress, stimulates NO production, and might contribute to pressure-induced natriuresis by impairing the autoregulation of papillary flow (Fenoy et al., 1995). To test this hypothesis and although it is known that cyclic GMP is under the control of several circulating agents such as atrial natriuretic peptide, we used its urinary excretion as an index of renal NO synthesis (Siragy et al., 1992). We observed that urinary excretion of cyclic GMP decreased during infusion of TA alone. However, when TA was given after PD 123319, urinary cyclic GMP excretion reached greater values than in controls. Finally, since PD 123319 given alone which, despite a surprising and unexplained increase in glomerular filtration rate, was devoid of effect on pressure-diuresis and -natriuresis, also increased urinary cyclic GMP, it became obvious that antinatriuretic properties of AT2 receptor stimulation could not be explained by a decreased formation or release of cyclic GMP in the kidney.

In conclusion, using a new highly specific agonist, we confirm that AT2 receptor stimulation blunts pressure-natriuresis, and can contribute to prevent the sodium losses induced by acute increases in blood pressure.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. It has been presented as an oral communication at the Eighth European Meeting on Hypertension, Milan, Italy (June, 1997). We gratefully acknowledge J. Sacquet for her technical assistance. PD 123319 and quinapril were generous gifts of Parke-Davis Laboratories.

Abbreviations

- ACE

angiotensin converting enzyme

- AI

angiotensin I

- AII

angiotensin II

- AT1

subtype 1 of angiotensin II receptor

- AT2

subtype 2 of angiotensin II receptor

- cyclic GMP

cyclic guanosine 3′, 5′ monophosphate

- NO

nitric oxide

- RPP

renal perfusion pressure

- TA

T2-(Ang II 4-8)2

References

- ARIMA S., ITO S., OMATA K., TSUNODA K., YAOITA H., ABE K.Activation of angiotensin II type 2 receptor (AT2) causes epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs)-dependent vasodilation in the micro-perfused rabbit afferent arterioles Hypertension 199628515(abstract) [Google Scholar]

- CHANG R.S.L., LOTTI V.J. Angiotensin receptor subtypes in rat, rabbit, and monkey tissues: Relative distribution and species dependency. Life Sci. 1991;49:1485–1490. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90048-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHATZIANTONIOU C., ARENDSHORST W.J. Angiotensin receptor sites in renal vasculature of rats developing genetic hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;265:F853–F862. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.265.6.F853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COGAN M.G., LIU F.Y., WONG P.C., TIMMERMANS P.B.M.W.M. Comparison of inhibitory potency by nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonists PD 123177 and Dup 753 on proximal nephron and renal transport. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;259:687–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENDO Y., ARIMA S., YAOITA H., OMATA K., TSUNODA K., TAKEUCHI K., ABE K., ITO S. Function of angiotensin II type 2 receptor in the postglomerular efferent arteriole. Kidney Int. 1997;52 Suppl. 63:S205–S207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAUBERT P.F., CHOU S.Y., PORUSH J.G. Regulation of papillary plasma flow by angiotensin II. Kidney Int. 1987;32:472–478. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FENOY F.J., FERRER P., CARBONELL L., SALOM M.G. Role of nitric oxide on papillary blood flow and pressure natriuresis. Hypertension. 1995;25:408–414. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISCHER T.A., SINGH K., HARA D.S., KAYE D.M., KELLY R.A. Role of AT1 and AT2 receptors in regulation of MAPKs and MKP-1 by ANG II in adult cardiac myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:H906–H916. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.3.H906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRANGER J.P. Pressure natriuresis: role of renal interstitial hydrostatic pressure. Hypertension. 1992;19 Suppl I:I9–I17. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.1_suppl.i9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GROUZMANN E., FELIX D., IMBODEN H., RAZANAME A., MUTTER M. A specific template-assembled peptidic agonist for the angiotensin II receptor subtype 2 (AT2) and its effect on inferior olivary neurones. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995;234:44–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.044_c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUYTON A.C. Long-term arterial pressure control: an analysis from animal experiments and computer and graphic models. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;259:R865–R877. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.259.5.R865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEIN L., BARSH G.S., PRATT R.E., DZAU V.J., KOBILKA B.K. Behavioural and cardiovascular effects of disrupting the angiotensin II type-2 receptor gene in mice. Nature. 1995;377:744–747. doi: 10.1038/377744a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICHIKI T., LABOSKY P.A., SHIOTA C., OKUYAMA S., IMAGAWA Y., FOGO A., NIIMURA F., ICHIKAWA I., HOGAN B.L.M., INAGAMI T. Effects on blood pressure and exploratory behaviour of mice lacking angiotensin II type-2 receptor. Nature. 1995;377:748–750. doi: 10.1038/377748a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISRAEL A., STROMBERG C., TSUTSUMI K., GARRIDO M.R., TORRES M., SAAVEDRA J.M. Angiotensin II receptor subtypes and phosphoinositide hydrolysis in rat adrenal medulla. Brain Res. Bull. 1995;38:441–446. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(95)02011-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEISER J.A., BJORK F.A., HODGES J.C., TAYLOR D.G., JR Renal hemodynamics and excretory responses to PD 123319 and losartan, non-peptide AT1 and AT2 subtype-specific angiotensin II ligands. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;262:1154–1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLINE R.L., LIU F. Modification of pressure natriuresis by long-term losartan in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1994;24:467–473. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.24.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU K.L., SASSARD J., BENZONI D. In the Lyon hypertensive rat, renal function alterations are angiotensin II dependent. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:R346–R351. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.2.R346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LO M., LIU K.L., LANTELME P., SASSARD J. Subtype 2 of angiotensin II receptors controls pressure-natriuresis in rats. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;95:1394–1397. doi: 10.1172/JCI117792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACARI D., BOTTARI S., WHITEBREAD S., DE GASPARO M., LEVENS N. Renal actions of the selective angiotensin AT2 receptor ligands CGP 42112B and PD 123319 in the sodium-depleted rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;249:85–93. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90665-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MADRID M.I., SALOM M.G., TORNEL J., GASPARO M., FENOY F.J. Effect of interaction between nitric oxide and angiotensin II on pressure diuresis and natriuresis. Am. J. Physiol. 1997a;273:R1676–R1682. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.5.R1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MADRID M.I., SALOM M.G., TORNEL J., GASPARO M., FENOY F.J. Interactions between nitric oxide and angiotensin II on renal cortical and papillary blood flow. Hypertension. 1997b;30:1175–1182. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.5.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARGULIES K.B., BURNETT J.C., JR Inhibition of cyclic GMP phosphodiesterases augments renal responses to atrial natriuretic factor in congestive heart failure. J. Card. Fail. 1994;1:71–80. doi: 10.1016/1071-9164(94)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATTSON D.L., RAFF H., ROMAN R.J. Influence of angiotensin II on pressure natriuresis and renal hemodynamics in volume-expanded rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;260:R1200–R1209. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.6.R1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOBES S., HARRIS P.J., YAMADA H., MENDELSOHN F.A.O. Effects of angiotensin II on renal cortical and papillary blood flows measured by laser-Doppler flowmetry. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;261:F998–F1006. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.261.6.F998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OZONO R., WANG Z.Q., MOORE A.F., INAGAMI T., SIRAGY H.M., CAREY R.M. Expression of the subtype 2 angiotensin (AT2) receptor protein in rat kidney. Hypertension. 1997;30:1238–1246. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.5.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAREKH N., ZOU A.P. Role of prostaglandins in renal medullary circulation: response to different vasoconstrictors. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:F653–F658. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.3.F653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRADELLES P., GRASSI J., CHABARDES D., GUISO N. Enzyme immunoassays of adenosine cyclic 3′,5′-monophosphate and guanosine cyclic 3′,5′-monophosphate using acetylcholinesterase. Anal. Chem. 1989;61:447–453. doi: 10.1021/ac00180a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RICHER C., DOUSSAU M.P., GIUDICELLI J.F. Effects of captopril and enalapril on regional vascular resistance and reactivity in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1983;5:312–320. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.5.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROMAN R.J., COWLEY A.W., JR Characterization of a new model for the study of pressure-natriuresis in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 1985;248:F190–F198. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1985.248.2.F190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROMAN R.J., COWLEY A.W. , JR, GARCIA-ESTAN J., LOMBARD J. Pressure-diuresis in volume-expanded rats: cortical and medullary hemodynamics. Hypertension. 1988a;12:168–176. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.12.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROMAN R.J., KALDUNSKI M.L., SCICLI A.G., CARRETERO O.A. Influence of kinins and angiotensin II on the regulation of papillary blood flow. Am. J. Physiol. 1988b;255:F690–F698. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1988.255.4.F690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUAN X., WAGNER C., CHATZIANTONIOU C., KURTZ A., ARENDSHORST W.J. Regulation of angiotensin II receptor AT1 subtypes in renal afferent arterioles during chronic changes in sodium diet. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:1072–1081. doi: 10.1172/JCI119235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIRAGY H.M., JOHNS R.A., PEACH M.J., CAREY R.M. Nitric oxide alters renal function and guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate. Hypertension. 1992;19:775–779. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.6.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSUZUKI S., MATOBA T., EGUCHI S., INAGAMI T. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor inhibits cell proliferation and activates tyrosine phosphatase. Hypertension. 1996;28:916–918. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.5.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN DER MARK J., KLINE R.L. Altered pressure natriuresis in chronic angiotensin II hypertension in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:R739–R748. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.3.R739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHU Z., ARENDSHORST W.J. Angiotensin II-receptor stimulation of cytosolic calcium concentration in cultured renal resistance arterioles. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:F1239–F1247. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.6.F1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHUO J., ALCORN D., HARRIS P.J., MENDELSOHN F.A.O. Localization and properties of angiotensin II receptors in rat kidney. Kidney Int. 1993;44 Suppl 42:S40–S46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHUO J., SONG K., HARRIS P.J., MENDELSOHN F.A.O. In vitro autoradiography reveals predominantly AT1 angiotensin II receptors in rat kidney. Renal Physiol. Biochem. 1992;15:231–239. doi: 10.1159/000173458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]