Abstract

Brief periods of myocardial ischaemia preceding a subsequent more prolonged ischaemic period 24–72 h later confer protection against myocardial infarction (‘delayed preconditioning' or the ‘second window' of preconditioning). In the present study, we examined the effects of pharmacological modifiers of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) induction and activity on delayed protection conferred by ischaemic preconditioning 48 h later in an anaesthetized rabbit model of myocardial infarction.

Rabbits underwent a myocardial preconditioning protocol (four 5 min coronary artery occlusions) or were sham-operated. Forty-eight hours later they were subjected to a sustained 30 min coronary occlusion and 120 min reperfusion. Infarct size was determined with triphenyltetrazolium staining. In rabbits receiving no pharmacological intervention, the percentage of myocardium infarcted within the risk zone was 43.9±5.0% in sham-operated animals and this was significantly reduced 48 h after ischaemic preconditioning with four 5 min coronary occlusions to 18.5±5.6% (P<0.01).

Administration of the iNOS expression inhibitor dexamethasone (4 mg kg−1 i.v) 60 min before ischaemic preconditioning completely blocked the infarct-limiting effect of ischaemic preconditioning (infarct size 48.6±6.1%). Furthermore, administration of aminoguanidine (300 mg kg−1, s.c.), a relatively selective inhibitor of iNOS activity, 60 min before sustained ischaemia also abolished the delayed protection afforded by ischaemic preconditioning (infarct size 40.0±6.0%).

Neither aminoguanidine nor dexamethasone per se had significant effect on myocardial infarct size. Myocardial risk zone volume during coronary ligation, a primary determinant of infarct size in this non-collateralized species, was not significantly different between intervention groups. There were no differences in systolic blood pressure, heart rate, arterial blood pH or rectal temperature between groups throughout the experimental period.

These data provide pharmacological evidence that the induction of iNOS, following brief periods of coronary occlusion, is associated with increased myocardial tolerance to infarction 48 h later.

Keywords: Ischaemic preconditioning, second window of protection, nitric oxide synthase, aminoguanidine, dexamethasone, myocardial infarction, rabbit

Introduction

Preconditioning myocardium with brief periods of ischaemia confers biphasic protection against later sustained ischaemia-reperfusion insult (Yellon et al., 1998). An early preconditioning effect appears rapidly after transient ischaemic stimuli and lasts approximately 1 h, while a delayed or ‘second window' of preconditioning (‘SWOP') develops many hours later and lasts for a few days. The delayed infarct-limiting effect of prior brief ischaemia has been confirmed in dog (Kuzuya et al., 1993), rabbit (Marber et al., 1993), rat (Yamashita et al., 1998) and pig myocardium (Muller et al., 1998).

Previously we have demonstrated that delayed preconditioning in rabbit myocardium was dependent on adenosine receptor activation (Baxter et al., 1994), protein kinase C activation (Baxter et al., 1995) and protein tyrosine kinase activity (Imagawa et al., 1997). However, the fact that delayed preconditioning requires many hours to be established suggests that the phenomenon is related to de novo synthesis of proteins which mediate or directly induce cardioprotection (Yellon & Baxter, 1995). In line with this inducible cytoprotective protein hypothesis, it has been demonstrated that the 72 kDa heat shock protein (hsp72) is upregulated 24 h after ischaemic preconditioning in rabbit myocardium (Marber et al., 1993), and in canine myocardium upregulation of manganese superoxide dismutase 24 h after preconditioning is temporally associated with cardioprotection (Hoshida et al., 1993; Kuzuya et al., 1993). However, so far evidence that these proteins are directly responsible for the protection observed in delayed preconditioning is elusive. Moreover, myocardial ischaemic stress is a complex stimulus and is known to involve the upregulation of many other proteins which could potentially be involved in the mediation of delayed cardioprotection.

Nitric oxide (NO), generated from various isoforms of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) has the potential to exhibit several beneficial effects in ischaemic tissue. These actions might be direct effects of NO on metabolism, such as reduction in oxygen utilization, or they might be exerted through cyclic GMP signalling. Several pieces of experimental evidence suggest that the inducible form of nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) might be involved in some forms of delayed adaptive cytoprotection: (i) Dexamethasone was shown to prevent the development of a delayed anti-arrhythmic protection 20 h after pacing-induced preconditioning in the dog (Vegh et al., 1994). This finding is compatible with the induction of iNOS since dexamethasone is known to inhibit the expression of iNOS (Radomski et al., 1990; Rees et al., 1990); (ii) Endotoxin-induced cardioprotection is abolished by treatment with dexamethasone in rats (Wu et al., 1996); (iii) We have shown a delayed myocardial protection 24 h after treatment with monophosphoryl lipid A, an endotoxin derivative, in the rabbit (Baxter et al., 1996), which could also be related to induction of iNOS; (iv) Aminoguanidine, a relatively selective inhibitor of iNOS activity (Griffiths et al., 1993; Misko et al., 1993) has been shown to block the delayed pharmacological preconditioning by monophosphoryl lipid A in a rabbit infarct model (Zhao et al., 1997) and (v) In a conscious rabbit model of myocardial stunning, Bolli et al. (1997) demonstrated that treatment with a non-selective NOS inhibitor, Nω-nitro-L-arginine, and the selective iNOS inhibitors aminoguanidine and S-methylisothiourea blocked the delayed anti-stunning effect of delayed preconditioning. This body of evidence suggests that iNOS may be induced by a variety of stimuli that evoke delayed myocardial protection.

In view of the preceding evidence, we hypothesized that transient ischaemia-reperfusion stress (ischaemic preconditioning), initiates the induction of iNOS and that this enzyme is a mediator of delayed cytoprotection during subsequent prolonged ischaemia through the enhanced generation of NO. We examined if the delayed infarct-limiting effect of ischaemic preconditioning was modified either by inhibition of iNOS induction with dexamethasone given during preconditioning ischaemia, or by inhibition of iNOS activity with aminoguanidine given before prolonged coronary artery occlusion. A preliminary account of these findings was presented to the British Cardiac Society at its annual meeting in May 1998 (Imagawa et al., 1998a).

Methods

Male New Zealand White rabbits (2.1–2.9 kg) were used throughout. Animals were allowed to acclimatize in the institutional animal house for around 1 week after delivery. They were allowed free access to a pelleted diet, water, and fresh hay. The care and use of animals in this work were in accordance with U.K. Home Office guidelines of the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. These experiments were divided into two parts as previously described (Marber et al., 1993; Baxter et al., 1994; 1997; Imagawa et al., 1997). Part 1 involved preparation of the animals in which ischaemic preconditioning was performed on day 1. Forty eight hours later, Part 2 of the procedure (myocardial infarction) was performed on day 3.

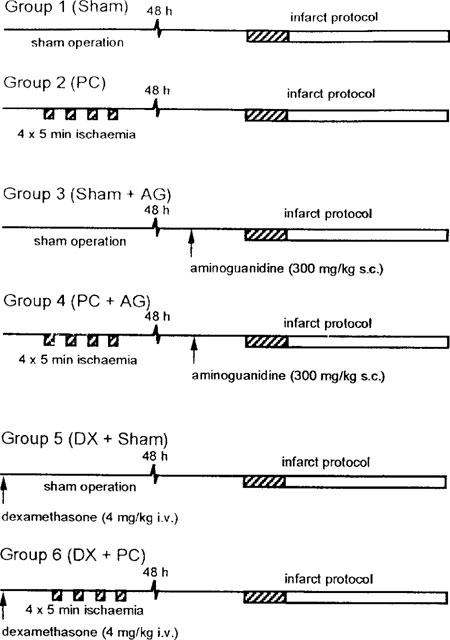

The experimental protocols are summarized in Figure 1. Animals were randomly assigned into six groups. Group 1 were sham-operated control animals without drug treatment (Sham). Group 2 were preconditioned without drug treatment (PC). Group 3 were sham-operated on day 1 and received aminoguanidine prior to infarction on day 3 (Sham+AG). Group 4 were preconditioned on day 1 and received aminoguanidine prior to infarction on day 3 (PC+AG). Group 5 were sham-operated on day 1 with dexamethasone treatment (DX+Sham). Group 6 were preconditioned on day 1 with dexamethasone treatment (DX+PC).

Figure 1.

Experimental groups and treatment protocols. Hatched areas indicate periods of myocardial ischaemia induced by coronary artery occlusion. Sham operation consisted of the positioning of a coronary ligature without occlusion. Preconditioning was performed by occlusion of a coronary artery for four 5 min periods each seperated by 10 min reperfusion. All animals were left for 48 h before the infarct protocol was peformed. This consited of 30 min coronary occlusion followed by 120 min reperfusion. Aminoguanidine was given 60 min before the infarct coronary occlusion. Dexamethasone was given 60 min before positioning of the coronary ligature in the sham operation or preconditioning groups.

During preparative surgery all groups received sterile normal saline (0.9% NaCl) infusion (approximately 3 ml kg−1). 60 min before coronary occlusion in the infarct procedure, animals received either saline 1 ml kg−1 s.c. (Groups 1, 2, 5 and 6) or aminoguanidine 300 mg kg−1 (Groups 3 and 4). Aminoguanidine was dissolved in saline at a concentration of 300 mg ml−1. The dexamethasone-treated groups received dexamethasone 4 mg kg−1 i.v. (20 mg ml−1 in ampoule) 60 min prior to the first preconditioning coronary occlusion.

Part 1: Ischaemic preconditioning or sham-operation

Animals were anaesthetized with a combination of 2 mg kg−1 i.v. diazepam and 0.3 ml kg−1 i.m. fentanyl citrate and fluanisone mixture (Hypnorm®). They were intubated with an orotracheal tube using a paediatric laryngoscope and ventilated with room air supplemented with O2 at a tidal volume of 5 ml kg−1 and a rate of approximately 1 Hz (small animal ventilator, Harvard Apparatus, Kent, U.K.). Electrodes were attached to shaved areas on each limb for recording of the surface ECG. The amplified ECG signals were recorded with an ECG amplifier and recorder (RS3400, Gould Instruments, Ilford, U.K.). A marginal ear vein was cannulated to administer drugs. Under antibiotic cover (5 mg kg−1 enrofloxacin, s.c.) and with aseptic technique, a median sternotomy and pericardiotomy were performed. An anterolateral branch of the circumflex coronary artery was identified, and a 3-0 silk suture (Mersilk type 546, Ethicon, Edinburgh, U.K.) was passed underneath the vessel at a point approximately halfway between the left atrioventricular groove and the apex. The ends of the suture were threaded through a 1.5 cm polypropylene tube to form a snare. The artery was occluded by pulling the ends of the suture taut and clamping the snare onto the epicardial surface. Snaring of the artery caused epicardial cyanosis and regional hypokinesis within 20–30 s and was usually accompanied by ST-segment elevation in the ECG within 1 min. After 5 min of ischaemia, reperfusion was instituted by releasing the snare. Successful reperfusion was confirmed by conspicuous blushing of the previous ischaemic myocardium and gradual resolution of the ECG changes. The preconditioning protocol consisted of four 5 min occlusions, each separated by 10 min reperfusion. After preconditioning, the loose suture was left in situ, the thorax was evacuated, and the sternotomy closed. Animals were extubated and allowed to recover from anaesthesia with postoperative analgesia (30 μg kg−1 buprenorphine HCl, i.m. and 1 mg kg−1 flunixin meglumine, s.c.). Sham-operated animals underwent the same surgical procedure, including pericardiotomy and positioning the coronary artery suture, without coronary occlusion. Approximately 24 h after surgical preparation, an antibiotic and an analgesic (5 mg kg−1 enrofloxacin, s.c. and 1 mg kg−1 flunixin meglumine, s.c.) were given to all animals.

Part 2: Infarction procedure

On day 3, approximately 48 h after operation on day 1, rabbits were reanaesthetized with a combination of 30 mg kg−1 pentobarbitone sodium (i.v.) and 0.15 ml kg−1 Hypnorm® (i.m.). Electrodes were attached to the shaved area on each limb for recording of the surface ECG. After the trachea was cannulated via a mid-line cervical incision under local anaesthetic (2% lignocaine HCl), animals were ventilated with room air supplemented with O2 and tidal volume was adjusted as necessary throughout the procedure to maintain arterial pH between 7.3 and 7.5 and pCO2 at <5.0 kPa. The rate of the ventilation was approximately 1 Hz. The right common carotid artery was cannulated with a short rigid polyethylene cannula attached to a pressure transducer (P23XL, Gould) for continuous recording of arterial blood pressure and intermittent arterial blood gas measurements (AVL993, AVL Medical Instruments U.K. Ltd, Stone, Staffs, U.K.). Rectal temperature was monitored periodically and maintained at 38.5±0.5°C with a heating pad. The thorax was reopened, and the in situ coronary ligature was used again for coronary occlusion. The artery was occluded for 30 min, followed by 120 min reperfusion by manipulating the ligature and snare as described above.

At the end of 120 min reperfusion, 1000 i.u. heparin sodium was administered before the heart was excised and Langendorff-perfused with saline solution to remove blood. The ligature was tightened again, and zinc-cadmium sulphide 1–10 μm microspheres were infused through the aorta to delineate the myocardium at risk under ultraviolet light. After freezing, the heart was sliced transversely from apex to base in 2 mm sections. The slices were defrosted, blotted and incubated at 37°C with 1% w/v triphenyltetrazolium chloride in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 10–20 min and fixed in 4% v/v formaldehyde solution for 2–7 days to clearly distinguish between stained viable tissue and unstained necrotic tissue. The volumes of the infarcted tissue and the tissue at risk were determined by a computerized planimetric technique (Summa Sketch II, Summa Graphics, Seymour, CT, U.S.A.).

Materials

We obtained aminoguanidine hemisulphate and triphenyltetrazolium chloride from Sigma Chemical (Poole, U.K.), dexamethasone sodium phosphate from Merck Sharp & Dohme (Hoddesden, U.K.), Hypnorm® from Janssen (Wantage, U.K.), diazepam from CP Pharmaceutical (Clwyd, U.K.), sodium pentobarbitone (Sagatal®) from Rhone Merieux (Dublin, Ireland), lignocaine HCl from Antigen Pharmaceuticals (Roscrea, Ireland), zinc-cadmium sulphide fluorescent microspheres (1–10 μm) from Duke Scientific (Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.), enrofloxacin (Baytril®) from Bayer (Suffolk, U.K.), flunixin meglumine (Finadyne®) from Schering-Plough (Suffolk, U.K.) and buprenorphine HCl (Vetergesic®) from Reckitt & Colman Products Ltd (Hull, U.K.). All other chemicals were of analytical reagent quality.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented throughout as means±s.e.mean. The significance of differences in mean values was evaluated by a one-way ANOVA. When treatment constituted a significant source of variance, Fisher's least significant difference test was used post hoc for predetermined individual group comparisons. The null hypothesis was rejected when P<0.05.

Results

Mortality and exclusions

A total of 46 rabbits were used for this study. Forty-five animals survived the preparation protocols. During Part 2, six animals were lost due to sustained ventricular fibrillation and/or systemic circulatory failure during the infarct protocol (two in Sham, three in DX+PC and one in DX+Sham) and two hearts (one in PC and one in PC+AG) were excluded due to an ischaemic myocardial risk volume less than 0.4 cm3 which was a prospectively determined exclusion criterion. One experiment was also excluded due to failure to determine clearly the risk zone in Sham group. The final numbers of animals were 36 (six in each group). Some of these animals had transient ventricular fibrillation during sustained ischaemia which reverted to sinus rhythm either spontaneously or with gentle tapping of the cardiac apex. However, there were no significant differences in the incidence of ventricular fibrillation between groups.

Myocardial infarct size

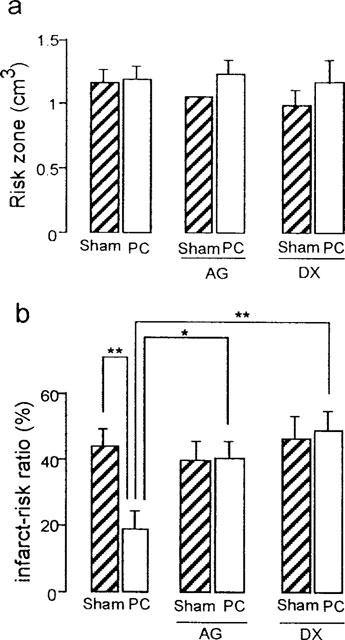

Ischaemic risk volumes during coronary occlusion were not significantly different between intervention groups at around 1.0 cm3 (Figure 2a). Percentage of infarction within the risk area was reduced from 43.9±5.0% in Sham group to 18.5±5.6% in PC group (P<0.01, Figure 2b). These infarct size values are consistent with our previous observation of infarct limitation associated with delayed preconditioning at 48 h (Baxter et al., 1997; Imagawa et al., 1997).

Figure 2.

Effects of aminoguanidine (AG) and dexamethasone (DX) on myocardial infarct size assessed after 30 min coronary occlusion followed by 120 min reperfusion in sham-operated (Sham) or ischaemically preconditioned (PC) rabbit hearts. (a) Myocardial risk zone volume. (b) Infarct size as a percentage of risk volume. Vertical bars depict mean with s.e.mean (n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (1-way ANOVA).

The inhibition of iNOS activity by aminoguanidine 60 min prior to sustained ischaemia, had virtually no effect on infarct size in sham-operated animals (39.4±6.0% in Sham+AG group vs 43.9±5.0% in Sham group, P>0.05, Figure 2b). However, this inhibitor completely abolished the delayed protection afforded by ischaemic preconditioning (40.0±6.0% in PC+AG group vs 18.5±5.6% in PC group, P<0.05, Figure 2b).

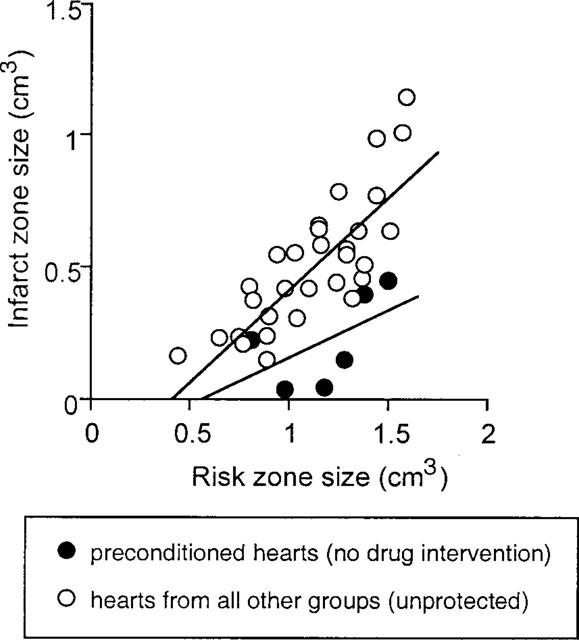

Dexamethasone given prior to the sham-operation had no significant effect on infarct size produced by sustained coronary occlusion 48 h later (46.7±6.7% in DX+Sham group vs 43.9±5.0% in Sham group, P>0.05, Figure 2b). However, dexamethasone given before ischaemic preconditioning abolished the delayed infarct-limiting effect of ischaemic preconditioning (48.6±6.1% in DX+PC group vs 18.5±5.6% in PC group, P<0.01, Figure 2b). Figure 3 shows the relation between risk region and infarct size for each animal. In all groups, there was a positive correlation between these two variables. These plots indicate that infarct size is dependent on the risk zone size and that distribution of the plots is clearly different between the PC group and the other five groups, indicating that the reduction in infarct size in PC group was independent of risk volume.

Figure 3.

Relation between absolute infarct and risk zone volumes for individual hearts. Closed circles indicate values from preconditioned hearts without any pharmacological inhibitors (protected hearts) (y=0.36×−0.20; r=0.53). Open circles indicate values from the remaining five groups of hearts (non-protected hearts) (y=0.71×−0.28; r=0.81). The regression line for preconditioned hearts is significantly different from the regression line for all other groups (P<0.05, analysis of covariance).

Haemodynamic responses and differences in arterial blood gases

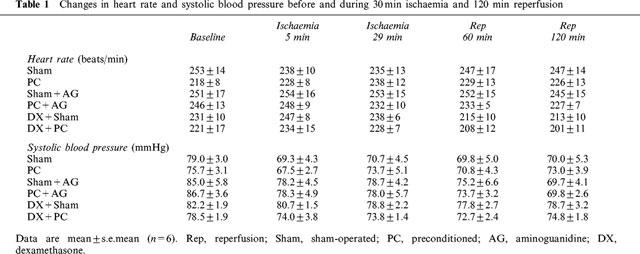

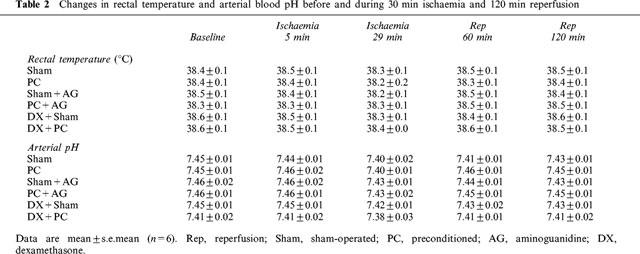

Table 1 describes the changes in systolic blood pressure and heart rate during sustained (30 min) coronary occlusion and subsequent 120 min reperfusion. There were no statistically significant differences in these haemodynamic parameters between groups throughout the experimental period. Although baseline blood pressure in PC group was somewhat lower than that in other groups, this was not statistically significant. Of particular note, aminoguanidine prior to coronary occlusion produced no significant effects on blood pressure or heart rate. Since temperature is a mjor determinant of the rate of infarction in ischaemic tissue, rectal temperature was strictly maintained at around 38.5°C (Table 2). Arterial blood pH tended to fall at 29 min after ischaemia and recovered after reperfusion in all groups. However, there were no statistically significant differences in blood pH between groups at any time points (Table 2).

Table 1.

Changes in heart rate and systolic blood pressure before and during 30 min ischaemia and 120 min reperfusion

Table 2.

Changes in rectal temperature and arterial blood pH before and during 30 min ischaemia and 120 min reperfusion

Discussion

The pertinent findings of the present study can be summarized as follows. Four 5 min coronary artery occlusions induced an adaptive response in myocardium (delayed preconditioning) which was associated with reduced myocardial infarct size following sustained coronary artery occlusion 48 h later. This result is consistent with previous reports of delayed preconditioning against infarction (e.g. Marber et al., 1993; Baxter et al., 1997; Imagawa et al., 1997; Qiu et al., 1997). A selective inhibitor of iNOS activity, aminoguanidine (Griffiths et al., 1993; Misko et al., 1993), when given before sustained ischaemia abolished the protection implying that iNOS activity is necessary during sustained ischaemia for the demonstration of delayed preconditioning. Dexamethasone, an inhibitor of iNOS expression (Radomski et al., 1990; Rees et al., 1990), completely abolished the delayed myocardial protection conferred by ischaemic preconditioning. The major conclusion of the present studies is that the induction and subsequent activation of iNOS appears to be necessary for development of delayed preconditioning in this experimental model. Our findings concur with work by Vegh's group in the canine model that dexamethasone prevents the development of delayed preconditioning against arrhythmias (Vegh et al., 1994). While this manuscript was in preparation, a report by Takano et al., (1998) was published which supports our data with respect to a role for nitric oxide synthase in delayed preconditioning against infarction in rabbit myocardium.

Effects of aminoguanidine and dexamethasone

Aminoguanidine is a selective inhibitor of iNOS (Griffiths et al., 1993; Misko et al., 1993). Under some experimental conditions the selectivity of this agent may be limited (Laszlo et al., 1995) and therefore we can not rule out the possibility that the constitutive form of NOS (cNOS) was also inhibited by aminoguanidine. However, the data tend to argue against any significant inhibition of cNOS by aminoguanidine in our experiments for the following reasons. First, we showed that aminoguanidine had no effect on infarct size per se whereas the inhibition of cNOS by non-selective NOS inhibitors significantly affects myocardial infarct size in this rabbit model of ischaemia-reperfusion (Patel et al., 1993; Williams et al., 1995). Secondly, the blood pressure in aminoguanidine-treated animals was not significantly higher than that in control animals before and during ischaemia and reperfusion periods in contrast to previous data showing marked hypertensive effects of non-selective NOS inhibitors in rabbits (Patel et al., 1993; Williams et al., 1995). These results would suggest the selectivity of aminoguanidine for iNOS over cNOS at the dose we used (300 mg kg−1, s.c.).

It has been reported that aminoguanidine has some effects other than NOS inhibition. Among them, an inhibitory effect on the antioxidant enzyme catalase (Ou & Wolff, 1993) might be involved in abrogation of delayed preconditioning by aminoguanidine since upregulation of endogenous antioxidant enzymes has been postulated as a mechanism of delayed preconditioning. However, the IC50 for aminoguanidine on catalase activity is reported to be 15 mM (Ou & Wolff, 1993), a value far in excess of the plasma concentration of aminoguanidine estimated from the dose we used. Therefore, we believe it unlikely that aminoguanidine significantly affects catalase activity in our experimental condition.

Dexamethasone has been reported to suppress the expression of iNOS in endothelial cells stimulated with interferon-γ and lipopolysaccharide (Radomski et al., 1990). The suppression would be mediated through inhibitory effect of the glucocorticoid on the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) (Auphan et al., 1995) and concomitant inhibition of cytokine production (Evans & Zuckerman, 1991). Because NF-κB activates many immunoregulatory genes in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli, the inhibition of its activity by dexamethasone would affect many kinds of biological activities including inducible cyclo-oxygenase (Masferrer et al., 1992). Thus dexamethasone is not a specific inhibitor of iNOS expression. At present, we can not exclude the possible involvement of cyclo-oxygenase products, such as prostacyclin, in delayed preconditioning against infarction since these mediators have not been systematically investigated in the phenomenon. However, the complete abrogation of delayed preconditioning by aminoguanidine, which is not a cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor, would suggest that the inhibitory effect of dexamethasone on delayed preconditioning is likely to be due to inhibition of iNOS expression, rather than inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase induction.

Possible mechanisms of iNOS induction

This evidence tends to support the hypothesis that NO may be an important mediator of delayed preconditioning proposed initially by Vegh et al. (1994) with respect to antiarrhythmic effects and subsequently by Bolli et al., (1997) with respect to anti-stunning effects. The present findings that NO may be a mediator of the infarct-limiting effects of delayed preconditioning are supported by the work of Takano et al. (1998) which was published while this manuscript was in preparation. This group reported that aminoguanidine treatment resulted in abolition of delayed preconditioning in rabbits when administered immediately prior to infarction.

Although the results of the present study suggest the involvement of iNOS in delayed cardioprotection conferred by ischaemic preconditioning, the mechanisms responsible for induction of iNOS by brief ischaemia have not been clarified. Our earlier work has clearly established that adenosine receptor activation during preconditioning is necessary for the triggering the development of delayed preconditioning against infarction. However, in other experimental models, it has been shown that a burst of oxygen free radicals is generated during the initial periods of brief, repetitive anoxia, and the radicals, including superoxide anion, are essential for triggering delayed cytoprotection 24 h later in isolated rat myocyte preparations (Zhou et al., 1996). Superoxide anion is converted to hydrogen peroxide, a well known activator of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) (Satriano & Achlondorff, 1994). NF-κB is essential for the induction of iNOS by lipopolysaccharide in murine macrophages (Xie et al., 1994). Activated NF-κB would mediate the induction of some cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor α and interleukin-1β, which have been shown to be potent inducers of iNOS in a variety of cells including macrophages, smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells (Moncada & Higgs, 1993). In addition, it has been reported that tyrosine kinase inhibitors abolish both NF-κB activation (Lee et al., 1997) and iNOS induction (Kleinert et al., 1996; LaPointe & Sitkins, 1996) conferred by stimulation with cytokines in many tissues including cardial myocytes. Therefore, ischaemic preconditioning might induce iNOS through a pathway involving free radicals, cytokines, tyrosine phosphorylation and NF-κB. Our previous data (Imagawa et al., 1997) showing inhibitory effects of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor on delayed preconditioning is consistent with this hypothesis.

The time course of iNOS induction after ischaemic preconditioning was not investigated in this study. However, it has been reported that the generation of NO by iNOS is maintained at least 48 h after stimulation with cytokines such as interferon γ and/or lipopolysaccharide in vascular endothelial cells (Radomski et al., 1990), colonic epithelial cell line (Kolios et al., 1995) and cardiac myocytes (Luss et al., 1995). In addition, a brief myocardial ischaemia enhanced production of NO metabolite 24–48 h later (Kim et al., 1997). From these results it might be possible that iNOS was activated 48 h after ischaemic preconditioning at which time point we observed delayed cardioprotection although the time course of iNOS induction might vary with experimental conditions.

Cardioprotection by NO

There is good evidence for a cardioprotective effect of NO under conditions of ischaemia and reperfusion. The mechanisms might include the reduction of myocardial oxygen demand concomitant with vasodilatory and negative inotropic effects of NO. However, in the present study the haemodynamic status was not different between any groups. Therefore it is unlikely that delayed protection is mediated by NO-induced decrease in myocardial oxygen demand. It has been reported that NO would protect myocardium from reperfusion injury via suppression of the activity of neutrophils (Lefer & Lefer, 1996). A recent report shows that peroxynitrite anion, which is formed by the interaction of superoxide and NO, is also cardioprotective through the inhibition of leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions in rats (Lefer et al., 1997). However, in the rabbit model (Birnbaum et al., 1997), in contrast to the dog (Chatelain et al., 1987) and rat (Hale & Kloner, 1991) models, only a small number of neutrophils infiltrated the myocardial area at risk following 30 min of ischaemia and 4 h reperfusion. Therefore it is unlikely that neutrophils play a major role in formation of myocardial infarction in our experimental model. Alternatively, recent experimental evidence has shown that NO enhances ATP-sensitive K channel (KATP) activity in rabbit cardiomyocytes (Cameron et al., 1996) and vascular smooth muscle cells from rabbit mesenteric arteries (Murphy & Brayden, 1995). We recently showed that a KATP channel opener, nicorandil, conferred cardioprotection in a rabbit myocardial infarct model (Imagawa et al., 1998b). Thus NO might protect ischaemic myocardium through activation of KATP channels in the rabbit heart. The involvement of KATP channels has been already reported in hyperthermia-induced (Pell et al., 1997), monophosphoryl lipid A-induced (Elliott et al., 1996) and adenosine A1 agonist-induced (Baxter & Yellon, 1998) delayed cardioprotection in a rabbit infarct model. It remains to be determined how opening of KATP channels protects myocardium from infarction and which channel is relevant to protection, i.e. the mitochondrial or the plasmalemmal KATP channel. At the present time, we hypothesize that NO is not the sole mediator or final effector molecule of delayed myocardial protection but it may modulate the activity of a distal effector, possibly the KATP channel.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate that delayed protection against myocardial infarction conferred by ischaemic preconditioning can be abolished by an iNOS expression inhibitor, dexamethasone, administered prior to preconditioning. Furthermore, in agreement with the recent work of Bolli's group, we observed that aminoguanidine, an inhibitor of iNOS activity, given prior to infarction also blocked the delayed protective effects of ischaemic preconditioning in our rabbit infarct model. Thus, it is likely that the induction and activation of iNOS are important steps in the development of delayed preconditioning in the rabbit and that NO might be a possible mediator of delayed cardioprotection.

Acknowledgments

Dr Baxter is supported by a British Heart Foundation personal fellowship (FS 97001). We thank the Hatter Foundation for continued support.

Abbreviations

- AG

aminoguanidine

- DX

dexamethasone

- hsp72

72 kDa heat shock protein

- cNOS

constitutive nitric oxide synthase

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- KATP

ATP-sensitive potassium channel

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- PC

preconditioning

- SWOP

second window of preconditioning

References

- AUPHAN N., DIDONATO J.A., ROSETTE C., HELMBERG A., KARIN M. Immunosuppression by glucocorticoids: inhibition of NFκB activity through induction of IκB synthesis. Science. 1995;270:286–290. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAXTER G.F., GOMA F.M., YELLON D.M. Involvement of protein kinase C in the delayed cytoprotection following sublethal ischemia in rabbit myocardium. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:222–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15866.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAXTER G.F., GOMA F.M., YELLON D.M. Characterisation of the infarct-limiting effect of delayed preconditioning: timecourse and dose-dependency studies in rabbit myocardium. Basic Res. Cardiol. 1997;92:159–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00788633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAXTER G.F., GOODWIN R.W., WRIGHT M.J., KERAC M., HEADS R.J., YELLON D.M. Myocardial protection after monophosphoryl lipid A: studies of delayed anti-ischaemic properties in rabbit heart. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:1685–1692. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAXTER G.F., MARBER M.S., PATEL V.C., YELLON D.M. Adenosine receptor involvement in a delayed phase of myocardial protection 24 hours after ischemic preconditioning. Circulation. 1994;90:2993–3000. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.6.2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAXTER G.F., YELLON D.M.Increased myocardial tolerance to ischaermia 24 h after adenosine A1 receptor stimulation: evidence for a role of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel Br. J. Pharmacol. 199812394P(proc suppl)(abstract) [Google Scholar]

- BIRNBAUM Y., PATTERSON M., KLONER R.A. The effect of CY1503, a sialyl Lewisx analog blocker of the selectin adhesion molecules, on infarct size and “no-reflow” in the rabbit model of acute myocardial infarction/reperfusion. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1997;29:2013–2025. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOLLI R., BHATTI Z.A., TANG X.-L., QIU Y., ZHANG Q., GUO Y., JADOON A.K. Evidence that late preconditioning against myocardial stunning in conscious rabbits is triggered by the generation of nitric oxide. Circ. Res. 1997;81:42–52. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMERON J.S., KIBLER K.K.A., BERRY H., BARRON D.N., SODDER V.H. Nitric oxide activates ATP-sensitive potassium channels in hypertrophied ventricular myocytes. FASEB J. 1996;10:A65. [Google Scholar]

- CHATELAIN P., LATOUR J.G., TRAN D., LORGERIL M.D., DUPRAS G., BOURASSA M. Neutrophil accumulation in experimental myocardial infarcts: relation with extent of injury and effect of reperfusion. Circulation. 1987;75:1083–1090. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.5.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLIOTT G.T., COMERFORD M.L., SMITH M.L., ZHAO L. Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion protection using monophosphoryl lipid A is abrogated by the ATP-sensitive potassium channel blocker, glibenclamide. Cardiovasc. Res. 1996;32:1071–1080. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EVANS G.F., ZUCKERMAN S.H. Glucocorticoid-dependent and – independent mechanisms involved in lipopolysaccharide tolerance. Eur. J. Immunol. 1991;21:1973–1979. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIFFITHS M.J.D., MESSENT M., MACALLISTER R.J., EVANS T.W. Aminoguanidine selectively inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;110:963–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13907.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALE S.L., KLONER R.A. Time course of infiltration and distribution of neutrophils following coronary artery reperfusion in the rat. Cor. Art. Dis. 1991;2:373–378. [Google Scholar]

- HOSHIDA S., KUZUYA T., FUJI H., YAMASHITA N., OE H., HORI M., SUZUKI K., TANIGUCHI N., TADA M. Sublethal ischemia alters myocardial antioxidant activity in canine heart. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:H33–H39. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.1.H33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IMAGAWA J., BAXTER G.F., YELLON D.M. Genistein, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, blocks the “second window of protection” 48 h after ischemic preconditioning in the rabbit. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1997;29:1885–1893. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IMAGAWA J., BAXTER G.F., YELLON D.M. Delayed preconditioning against infarction may involve inducible nitric oxide synthase. Heart. 1998a;79 suppl 1:P10. [Google Scholar]

- IMAGAWA J., BAXTER G.F., YELLON D.M. Myocardial protection afforded by nicorandil and ischaemic preconditioning in a rabbit infarct model in vivo. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1998b;31:74–79. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199801000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM S.-J., GHALEH B., KUDEJ R.K., HUANG C.-H., HINTZE T.H., VANTER S.F. Delayed enhanced nitric oxide-mediated coronary vasodilation following brief ischemia and prolonged reperfusion in conscious dogs. Circ. Res. 1997;81:53–59. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEINERT H., EUCHENHOFER C., IHRIG-BIEDERT I., FORSTERMANN U. In murine 3T3 fibroblasts, different second messenger pathways resulting in the induction of NO synthase II (iNOS) converge in the activation of transcription factor NFκB. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:6039–6044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOLIOS G., BROWN Z., ROBSON R.L., ROBERTSON D.A., WESTWICK J. Inducible nitric oxide synthase activity and expression in a human colonic epithelial cell line, HT-29. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:2866–2872. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUZUYA T., HOSHIDA S., YAMASHITA N., FUJI H., OE H., HORI M., KAMADA T., TADA M. Delayed effects of sublethal ischemia on the acquisition of tolerance to ischemia. Circ. Res. 1993;72:1293–1299. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.6.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAPOINTE M.C., SITKINS J.R. Mechanisms of interleukin-1β regulation of nitric oxide synthase in cardiac myocytes. Hypertension. 1996;27:709–714. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LASZLO F., EVANS S.M., WHITTLE B.J.R. Aminoguanidine inhibits both constitutive and inducible nitric oxide synthase isoforms in rat intestinal microvasculature in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;272:169–175. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)00637-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE B.S., KANG H.S., PYUN K.H., CHOI I. Roles of tyrosine kinases in the regulation of nitric oxide synthesis in murine liver cells: modulation of NFκB activity by tyrosine kinases. Hepatol. 1997;25:913–919. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEFER A.M., LEFER D.J. The role of nitric oxide and cell adhesion molecules on the microcirculation in ischemia-reperfusion. Cardiovasc. Res. 1996;32:743–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEFER D.J., SCALIA R., CAMPBELL B., NOSSULI T., HAYWARD R., SALAMON M., GRAYSON J., LEFER A.M. Peroxynitrite inhibits leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions and protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:684–691. doi: 10.1172/JCI119212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUSS H., WATKINS S.C., FREESWICK P.D., IMRO A.K., NUSSLER A.K., BILLAR T.R., SIMMONS R.L., DEL-NIDO P.J., MCGOWAN F.X., JR Characterization of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in endotoxemic rat cardiac myocytes in vivo and following cytokine exposure in vitro. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1995;27:2015–2029. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(95)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARBER M.S., LATCHMAN D.S., WALKER J.M., YELLON D.M. Cardiac stress protein elevation 24 hours after brief ischemia or heat stress is associated with resistance to myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1993;88:1264–1272. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASFERRER J.L., SEIBERT K., ZWEIFEL L., NEEDLEMAN P. Endogenous glucocorticoids regulate an inducible cyclooxygenase enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:3917–3921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MISKO T.P., MOORE W.M., KASTEN T.P., NOCKOLS G.A., CORBETT J.A., TILTON R.G., MCDANIEL M.L., WILLIAMSON J.R., CURRIE M.G. Selective inhibition of the inducible nitric oxide synthase by aminoguanidine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;223:119–125. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90357-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONCADA S., HIGGS A. The L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway. New Engl. J. Med. 1993;329:2002–2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULLER C.A., BAXTER G.F., LATOUF S.E., MCCARTHY J., OPIE L.H., YELLON D.M.Delayed preconditioning against infarction in pig heart after PTCA balloon inflations J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 199830A(abstract) [Google Scholar]

- MURPHY M.E., BRAYDEN J.E. Nitric oxide hyperpolarizes rabbit mesenteric arteries via ATP-sensitive potassium channels. J. Physiol. 1995;486:47–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OU P., WOLFF S.P. Aminoguanidine: A drug proposed for prophylaxis in diabetes inhibits catalase and generates hydrogen peroxide in vitro. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1993;46:1139–1144. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATEL V.C., YELLON D.M., SINGH K.J., NEILD G.H., WOOLFSON R.G. Inhibition of nitric oxide limits infarct size in the in situ rabbit heart. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1993;194:234–238. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PELL T.J., YELLON D.M., GOODWIN R.W., BAXTER G.F. Myocardial ischaemic tolerance following heat stress is abolished by ATP-sensitive potassium channel blockade. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 1997;11:679–686. doi: 10.1023/a:1007791009080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QIU Y., RIZVI A., TANG X.L., MANCHIKALAPUDI S., TAKANO H., JADOON A.K., WU W.-J., BOLLI R. Nitric oxide triggers late preconditioning against myocardial infarction in conscious rabbits. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:H2931–H2936. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.6.H2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADOMSKI M.W., PALMER R.M.J., MONCADA S. Glucocorticoids inhibit the expression of an inducible, but not constitutive nitric oxide synthase in vascular endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:10043–10047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.10043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REES D.D., CELLEK S., PALMER R.M.J., MONCADA S. Dexamethasone prevents the induction by endotoxin of a nitric oxide synthase and the associated effects of vascular tone: an insight into endotoxin shock. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1990;173:541–547. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SATRIANO J., ACHLONDORFF D. Activation and attenuation of transcription factor NFκB in mouse glomerular mesangial cells in response to tumour necrosis factor-α, immunogloblin G, and adenosine 3′ : 5′-cyclic monophosphate. Evidence for involvement of reactive oxygen species. J. Clin. Invest. 1994;94:1629–1636. doi: 10.1172/JCI117505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKANO H., MANCHIKALAPUDI S., TANG X.-L., QIU Y., RIZVI A., JADOON A.K., ZHANG Q., BOLLI R. Nitric oxide synthase is the mediator of late preconditioning against myocardial infarction in conscious rabbits. Circulation. 1998;98:441–449. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.5.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VEGH A., PAPP J.G., PARRATT J.R. Prevention by dexamethasone of the marked antiarrhythmic effects of preconditioning induced 20 h after rapid cardiac pacing. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;113:1081–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17104.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS M.W., TAFT C.S., RAMNAUTH S., ZHAO Z.-Q., VINTEN-JOHANSEN J. Endogenous nitric oxide (NO) protects against ischaemia-reperfusion injury in the rabbit. Cardiovasc. Res. 1995;30:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU S., FURMAN B.L., PARRATT J.R. Delayed protection against ischaemia-induced ventricular arrhythmias and infarct size limitation by the prior administration of Escherichia Coli endotoxin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:2157–2163. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XIE Q.W., KASHIWABARA Y., NATHAN C. Role of transcription factor NFκB/Rel in induction of nitric oxide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:4705–4708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMASHITA N., NOSHIDA S., TANIGUCHI N., KUZUYA T., HORI M. A ‘second window of protection' occurs 24 hours after ischemic preconditioning in rat heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1998;30:1181–1189. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMASHITA N., NISHIDA S., HOSHIDA S., KUZUYA T., HORI M., TANIGUCHI N., KAMADA T., TADA M. Induction of manganese superoxide dismutase in rat cardiac myocytes increases tolerance to hypoxia 24 hours after preconditioning. J. Clin. Invest. 1994;94:2193–2199. doi: 10.1172/JCI117580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YELLON D.M., BAXTER G.F. A “second window of protection” or delayed preconditioning phenomenon: future horizons for myocardial protection. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1995;27:1023–1034. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(95)90071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YELLON D.M., BAXTER G.F., GARCIA-DORADO D., HEUSCH G., SUMERAY M.S. Ischaemic preconditioning: present position and future directions. Cardiovasc. Res. 1998;37:21–33. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHAO L., WEBER P.A., SMITH J.R., COMERFORD M.L., ELLIOTT G.T. Role of inducible nitric oxide synthase in pharmacological “preconditioning” with monophosphoryl lipid A. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1997;29:1567–1576. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU X., ZHAI X., ASHRAF M. Direct evidence that initial oxidative stress triggered by preconditioning contributes to second window of protection by endogenous antioxidant enzyme in myocytes. Circulation. 1996;93:1177–1184. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.6.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]