Abstract

Thrombin has well characterized pro-inflammatory actions that have recently been suggested to occur via activation of its receptor, proteinase-activated receptor-1 (PAR1).

In the present study, we have compared the effects of thrombin to those of two peptides that selectively activate the PAR1 receptor, in a rat hindpaw oedema model. We have also examined whether or not thrombin can exert anti-inflammatory activity in this model.

Both thrombin and the two PAR1 activating peptides induced significant oedema in the rat hindpaw following subplantar injection.

The oedema induced by thrombin was abolished by pre-incubation with hirudin, and was markedly reduced in rats in which mast cells were depleted through treatment with compound 48/80 and in rats pretreated with indomethacin. In contrast, administration of the PAR1 activating peptides produced an oedema response that was not reduced by indomethacin and was only slightly reduced in rats pretreated with compound 48/80.

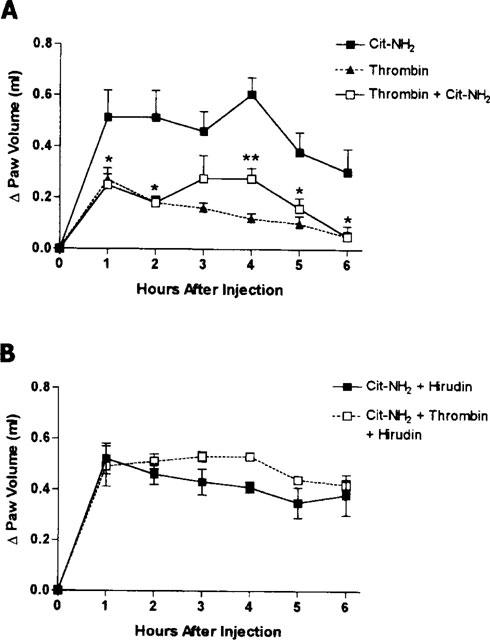

Co-administration of thrombin together with a PAR1 activating receptor resulted in a significantly smaller oedema response than that seen with the PAR1 activating peptide alone. This anti-inflammatory effect of thrombin was abolished by pre-incubation with hirudin.

These results demonstrate that the pro-inflammatory effects of thrombin occur through a mast-cell dependent mechanism that is, at least in part, independent of activation of the PAR1 receptor. Moreover, thrombin is able to exert anti-inflammatory effects that are also unrelated to the activation of PAR1.

Keywords: Thrombin, protease-activated receptor, inflammation, mast cell, prostaglandin, nitric oxide

Introduction

Well recognized for its role in the coagulation cascade, thrombin is now known to affect its target tissues, in part, via the proteolytic activation of cell surface G-protein-coupled receptors (Rasmussen et al., 1991; Vu et al., 1991; Ishihara et al., 1997; Xu et al., 1998). The unique mechanism whereby thrombin activates its G-protein-coupled receptors involves the proteolytic unmasking of an N-terminal amino acid sequence that acts as a tethered, self-activating ligand. Three of these Proteolytically-Activated-Receptors (PARs) for thrombin have now been described (PAR1, PAR3 and PAR4), with distinct tethered-ligand sequences (SFLLRNPN… for human PAR1 and TFRGAPPN… for human PAR3; (Vu et al., 1991; Ishihara et al., 1997); GYPGQV… for human PAR4; (Xu et al., 1998; Kahn et al., 1998). A remarkable property for PAR1 (but not PAR3) is that synthetic peptides based on the proteolytically-revealed PAR1 sequence (e.g., SFLLR-NH2), in isolation, are able to activate the receptor, so as to mimic the actions of thrombin in platelets or other target tissues (Vu et al., 1991; Hollenberg et al., 1992). The pharmacology of PAR4 has yet to be studied in depth, but does not appear to be triggered by PAR1-activating peptides. PAR3, which rather than PAR1, represents the thrombin-activated receptor in rodent platelets, is not activated by synthetic peptides based either on its own revealed tethered ligand (TFRGAP-NH2) or on the PAR1-activating peptides (formerly termed thrombin receptor-activating peptides, or TRAPs, such as SFLLR-NH2). Nonetheless, PAR1-activating peptides, like SFLLR-NH2 are also able to activate PAR2, a proteinase-activated receptor triggered by trypsin but not thrombin. PAR2, which is distinct from three thrombin receptors cloned to date (Nystedt et al., 1994) and has a unique tethered ligand sequence (SLIGRL…). Because of the ability of the above-mentioned PAR1-derived peptides to activate both PAR1 and PAR2 (Blackhart et al., 1996; Hollenberg et al., 1997), we have sought to develop selective PAR1 activating peptides by altering the peptide sequence derived from the tethered ligand of human PAR1. We have found that two peptides, TFLLR-NH2 (TF-NH2) (Hollenberg et al., 1997) and AparafluoroFRCyclohexylACitY-NH2 (Cit-NH2) (Vergnolle et al., 1998) are highly selective for PAR1, compared with PAR2, and can therefore be used as surrogates for thrombin to activate PAR1 in vivo, without concurrently activating PAR2.

Apart from causing effects on target cells via the proteolytic activation of the G-protein-coupled receptors, PAR1, PAR3 and PAR4, thrombin also exhibits chemotactic and mitogenic activity due to two peptide sequences that lie outside its catalytic domain (Bar-Shavit et al., 1983; 1984; Herbert et al., 1994; Stiernberg et al., 1993; Glenn et al., 1988). These non-catalytic actions of thrombin, in addition to its ability to catalyze the formation of fibrin, may contribute to the potential role of thrombin in the inflammatory response. Previous work has shown that thrombin can cause effects that accompany an inflammatory response, including increased vascular permeability (Malik & Fenton, 1992), degranulation of mast cells (Razin & Marx, 1984), increased endothelial adhesion of neutrophils (Toothill et al., 1990), chemotaxis and aggregation of neutrophils (Bizios et al., 1986) and stimulation of cytokine release from endothelial cells (Stankova et al., 1995; Ueno et al., 1996) and from vascular smooth muscle (Kranzhofer et al., 1996). The precise role of the thrombin receptors (PAR1, PAR3 or PAR4) in these pro-inflammatory actions of thrombin is of considerable interest. In a recent study, Hirulog was observed to attenuate the inflammatory effect of thrombin in a carrageenan-induced rat paw oedema model (Cirino et al., 1996). Since Hirulog (a derivative of hirudin) can bind both to the catalytic site and the anion-binding exosite of thrombin (Maraganore et al., 1990; Skrzypczak-Jankun et al., 1991), it could block the actions of thrombin mediated both by the catalytic activation of PARs and by the non-catalytic activities of the exosite mitogenic/chemotactic peptide domains. To distinguish between these alternatives, Cirino et al. (1996) made use of the PAR1-activating peptide, SFLLRNPNDKYEPF (TRAP-14), to evaluate its actions in the paw oedema model in comparison with thrombin. Because TRAP-14 mimicked the oedema response elicited by thrombin, causing mast cell degranulation and increased vascular permeability, it was concluded that the pro-inflammatory effects of thrombin were due to its activation of PAR1. However, as pointed out above, data appearing subsequent to the study of Cirino et al. (1996) show that TRAP-14 can activate both PAR1 and PAR2 (Blackhart et al., 1996; Hollenberg et al., 1997; Kawabata et al.,1999), and that TRAP-14 is not able to activate PAR3 (Ishihara et al., 1997). Thus, the conclusion that PAR1 activation alone accounts for the pro-inflammatory actions of thrombin, based on the inflammatory action of TRAP-14, requires a re-evaluation.

In view of the above discussion, the work we describe in this report was done with two aims in mind. First, we wished to use our newly developed PAR1-selective activating peptides (TF-NH2 and Cit-NH2) to determine if they would, like TRAP-14, mimic the actions of thrombin in a rat paw oedema model of inflammation. Second, we wished to examine in further detail, the mechanism and extended time course of the inflammatory response induced by thrombin and the selective PAR1-activating peptides (PAR1APs). Our data show that PAR1 activation alone cannot account for all of the effects of thrombin in this model of inflammation. Moreover, our results reveal a novel anti-inflammatory action of thrombin that has yet to be appreciated.

Methods

Animals

Male, Wistar rats (175–200 g) were obtained from Charles River Breeding Farms (Montreal, QC, Canada). The rats had free access to food and water and were housed under constant temperature (22°C) and photoperiod (12-h light-dark cycle). All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the University of Calgary and were performed in accordance with the guidelines established by the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

Paw oedema

A basal recording of paw volume was made using a hydroplethismometer (Ugo Basile, Milan, Italy). The rats were lightly anaesthetized with Halothane (5%). A subplantar injection of one of the test substances was then made (n=5 per group in all experiments). The test substances were always injected as a total volume of 0.1 ml. The test substances were initially dissolved in HEPES (25 mM, pH 7.4), then diluted in sterile 0.9% saline to give the desired concentration. The test substances included thrombin (1.5 and 20 U per paw), the PAR1APs, Cit-NH2 and TF-NH2 (500 μg), and the control peptide FSLLRY-NH2 (FS-NH2; 500 μg). Paw volume was measured every hour for 6 h after the injection.

To determine whether or not any pro-inflammatory activity of thrombin was due to its proteolytic activity, additional experiments were performed in which subplantar injections of thrombin (5 U per paw), hirudin (5 U per paw) or thrombin+hirudin (5 U of each pre-incubated together for 20 min at 37°C before the injection) were performed. Hirudin binds to thrombin, inhibiting its proteolytic activity.

For the evaluation of the effects of drugs on oedema formation, some groups of rats were pretreated with indomethacin (5 mg kg−1, p.o.) or Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME; 25 mg kg−1, i.p.) 1 h before the subplantar injection of thrombin or a PAR1AP. The control groups received the vehicles for indomethacin and L-NAME (5% NaHCO3 and saline, respectively). Other groups of rats were treated with compound 48/80 to deplete mast cells in the paw, as described by Di Rosa et al. (1971). Briefly, compound 48/80 (0.1% solution in 0.9% sterile saline) was injected intraperitoneally each morning and evening for 4 days prior to the paw oedema experiment. The doses employed were 0.6 mg kg−1 for the first six injections and 1.2 mg kg−1 for the last two injections. The test substances in the paw oedema experiments were administered 5–6 h after the final injection of compound 48/80.

Effects of thrombin on PAR1AP-induced paw oedema

Paw oedema experiments were performed, as described above, except that each rat received two injections (50 μl each) into a hindpaw. Four groups of rats (n=5 in each) were studied: (i) thrombin (5 U) plus vehicle, (ii) PAR-1AP (500 μg) plus vehicle, (iii) thrombin (5 U) plus PAR1AP (500 μg), and (iv) vehicle alone (100 μl). The PAR1AP used in these experiments was Cit-NH2. Additional experiments were then performed in which rats received subplantar injections of Cit-NH2 (500 μg) plus hirudin (5 U per paw) or Cit-NH2 (500 μg) together with thrombin+hirudin (5 U of each pre-incubated together for 20 min at 37°C before the injection).

Histology

Rats (n=6 per group) were given a 0.1 ml subplantar injection of either the inactive peptide FS-NH2 (500 μg), the PAR1APs Cit-NH2 (500 μg) and TF-NH2 (500 μg), or vehicle and were killed 6 h later. The injected paws were removed and fixed by immersion in formalin for 24 h before being embedded in paraffin wax. Sections (5 μm) were cut and stained with haematoxylin and eosin to reveal structural features.

Materials

All peptides, prepared by solid phase synthesis, were obtained from the peptide synthesis facility of the University of Calgary Faculty of Medicine (director, Dr D. McMaster). The composition and the purity of all peptides were confirmed by HPLC analysis, mass spectral analysis and amino acid analysis. Stock solutions prepared in HEPES buffer, pH 7.4 (25 mM), were analysed by quantitative amino acid analysis to verify peptide concentration and purity. Thrombin (EC 3.4.21.5, 1460 NIH units mg−1), hirudin, indomethacin, L-NAME and compound 48/80 were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.).

Statistical analysis

All results are reported as means±s.e.mean. Comparisons among groups were performed using the two-sided Student's t-test with Bonferroni correction. With all statistical analyses, an associated probability (P value) of less than 5% was considered significant.

Results

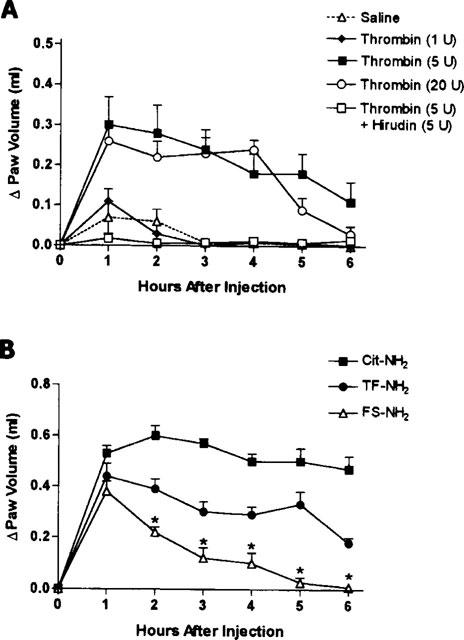

Oedema induced by thrombin

Injection of thrombin into the rat hindpaw resulted in the development of oedema which persisted for up to 6 h (Figure 1). At the lowest concentration tested (1 U per paw), the magnitude of the oedema response was not significantly different from that observed following injection of vehicle. With higher concentrations of thrombin (5 and 20 U per paw), a more profound and long-lasting oedema response was observed. No difference in the magnitude of the oedema was observed between the 5 and 20 U per paw doses.

Figure 1.

(A) Increase in rat hindpaw volume following injection of thrombin or thrombin that had been pre-incubated with hirudin. Thrombin caused significant oedema formation at doses of 5 and 20 U per paw. The pre-incubation of thrombin with hirudin resulted in a significant reduction in oedema at hours 1 through 5 post-injection (P<0.05). (B) Increase in rat hindpaw volume following injection of a PAR1 activating peptide (Cit-NH2 and TF-NH2, each at 500 μg paw−1) or a control peptide (FS-NH2, 500 μg paw−1). Asterisks denote significant differences (P<0.05) between the control peptide group and the other two groups.

To verify that the observed oedema was produced through the action of thrombin itself, we tested the effects of thrombin (5 U per paw) that had been pre-incubated with the thrombin inhibitor, hirudin (5 U). No oedema was observed after the injection of thrombin+hirudin (Figure 1A) or the injection of hirudin alone (5 U per paw; not shown).

Inflammation induced by PAR1APs

The two selective PAR1APs (Cit-NH2 and TF-NH2) each induced a significant oedema response when injected into the rat hindpaw (Figure 1B). In each case, the oedema response was significantly greater (from the second hour through the sixth hour) than that observed when the control peptide was injected. Notwithstanding, the partial reverse-sequence peptide, FS-NH2, which is unable to activate PAR1, did yield an oedema response between 1 and 2 h that was greater than that seen with saline alone (Figure 1B). The oedema response to Cit-NH2 was about 2 fold greater than that observed with thrombin.

Histologic examination of paws injected with the PAR1-APs Cit-NH2 and TF-NH2, revealed a complete disruption of tissue architecture and oedema, as compared with control tissue sections of rat injected with vehicle. The tissues of rat paws injected with the control peptide FS-NH2 exhibited some disruption of tissue architecture but less marked than that observed after PAR1APs injection. Numerous granulocytes were evident in the paws of rats injected with the two PAR1-APs (Cit-NH2 and TF-NH2), but no infiltrating cells were observed in the paws of rats injected either with the inactive peptide FS-NH2 or with vehicle.

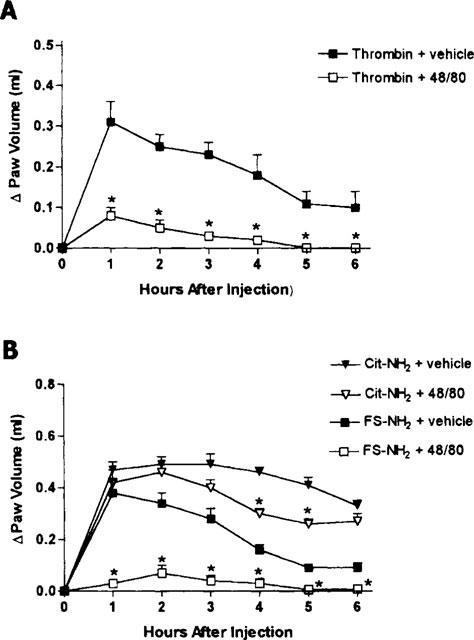

Role of mast cells

Prior treatment with compound 48/80 resulted in an oedema response to thrombin that was no greater that the administration of saline alone (Figures 1A and 2A). The oedema observed following injection of the control peptide (FS-NH2) was also reduced to control levels by pretreatment of the animals with compound 48/80 (Figure 2B). In contrast, compound 48/80 only produced a small reduction (significant at the fourth and fifth hour) in the oedema response to the selective PAR1AP, Cit-NH2 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Effects of prior depletion of mast cells (through pretreatment with compound 48/80) on the increase in hindpaw volume following injection of thrombin. The two groups differed significantly (P<0.05) at hours 1 through 6 post-injection. (B) Effects of prior depletion of mast cells on the increase in hindpaw volume following injection of a PAR1 activating peptide (Cit-NH2) or a control peptide (FS-NH2). Asterisks denote significant differences from the corresponding group not treated with compound 48/80.

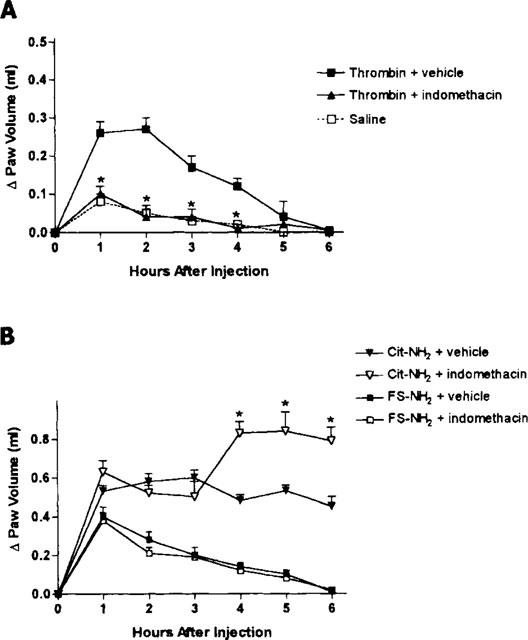

Role of prostaglandins

Pretreatment with indomethacin abolished the oedema induced by thrombin (Figure 3A). In contrast, indomethacin pretreatment resulted in a significant increase in the oedema induced by the PAR1AP, Cit-NH2, and had no effect on the oedema induced by the control peptide, FS-NH2 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) Effects of pretreatment with the cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor, indomethacin (5 mg kg−1), on the increase in hindpaw volume following injection of thrombin. Indomethacin pretreatment had no significant effect on the oedema response. (B) Effects of pretreatment with indomethacin (5 mg kg−1) on the increase in hindpaw volume following injection of a PAR1 activating peptide (Cit-NH2) or a control peptide (FS-NH2). Indomethacin significantly increased (*P<0.05) the oedema response to the PAR1AP, while having no effect on the response to the control peptide.

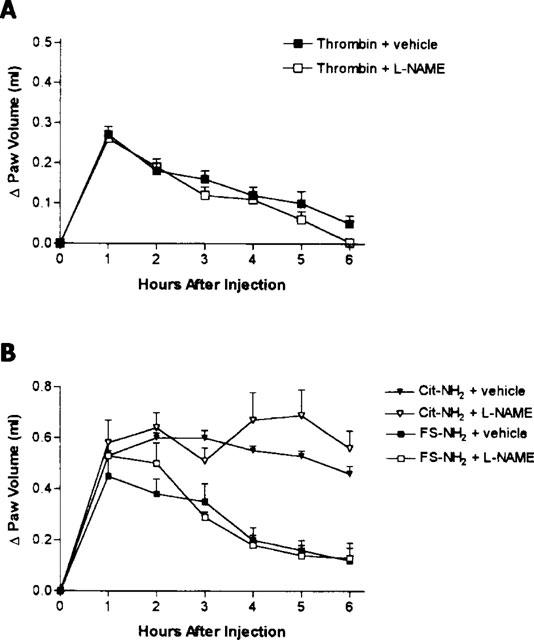

Role of nitric oxide

Pretreatment with L-NAME did not significantly affect the oedema response to thrombin (Figure 4A), nor did it affect the oedema response to the Cit-NH2, or the control peptide, FS-NH2 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

(A) Effects of pretreatment with the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, L-NAME (25 mg kg−1), on the increase in hindpaw volume following injection of thrombin. L-NAME pretreatment had no significant effect on the oedema response. (B) Effects of pretreatment with L-NAME (25 mg kg−1) on the increase in hindpaw volume following injection of a PAR1 activating peptide (Cit-NH2) or a control peptide (FS-NH2). L-NAME pretreatment had no significant effect on the oedema response.

Effects of thrombin+PAR1-activating peptide

Co-administration of thrombin with the PAR1AP, Cit-NH2, resulted in a significant reduction (by ∼50%) of the oedema response compared to that produced by the PAR1AP alone (Figure 5A). Administration of hirudin together with Cit-NH2 had no effect on the oedema response compared to that seen with Cit-NH2 alone. However, hirudin completely blocked the anti-inflammatory effect of thrombin (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

(A) Effects of subplantar co-administration of thrombin (5 U per paw) and the PAR-1 activating peptide (Cit-NH2) on hindpaw volume. The oedema response following administration of thrombin and the PAR1AP was significantly smaller than that produced by injection of the PAR1AP alone (*P<0.05 versus the group treated with PAR1AP alone). (B) Effects of hirudin on the oedema response to the PAR1-activating peptide, Cit-NH2, and on the anti-inflammatory effect of thrombin observed when it was co-administered with Cit-NH2.

Discussion

The ability of thrombin to activate human platelets and to influence the function of numerous other cells is mediated through the proteolytic activation of a receptor that is now referred to as PAR1 (Vu et al., 1991; Hollenberg, 1996). In the present study, we have demonstrated that thrombin can exert both pro- and anti-inflammatory actions, and that these actions occur, at least in part, through mechanisms distinct from the activation of PAR1. These conclusions are based on our observation that thrombin has a different profile of activity in the paw oedema assay than two selective PAR1APs. For example, the oedema induced by thrombin was almost completely abolished by prior depletion of mast cells (with compound 48/80) and by pretreatment with indomethacin. In contrast, the oedema induced by the PAR1APs was slightly increased (Cit-NH2) or not affected (TF-NH2) by indomethacin pretreatment, and only marginally reduced in rats treated with compound 48/80. Moreover, the combined administration of thrombin and a selective PAR1AP revealed anti-inflammatory effects of thrombin, in that the magnitude of the oedema response was significantly less (∼50%) than that observed following injection of the PAR1AP alone.

Cirino et al. (1996) recently reported that the pro-inflammatory effects of thrombin were mediated through activation of PAR1. This conclusion was based on their observations that injection of TRAP-14 resulted in paw oedema similar to that seen with thrombin itself. They also demonstrated that the pro-inflammatory effects of TRAP-14 were almost completely inhibited by compound 48/80 and attenuated to some extent by indomethacin. Our observations with respect to thrombin were consistent with those of Cirino et al. (1996), but the observations with respect to TRAP-14 and our new PAR1APs were divergent. These discrepancies may be explained by differences in the time frame of the two studies, and in the lack of selectivity of TRAP-14 for PAR1 (Blackhart et al., 1996; Hollenberg et al., 1997; Kawabata et al., 1999). In the present study, the oedema responses were monitored for 6 h following injection of the test substances, while in the study of Cirino et al. (1996), the responses were monitored for only 90 min. Surprisingly, we found that a significant oedema response (compared to that observed with saline alone) could be detected during the first 1–2 h following the administration of a control peptide (FS-NH2) that cannot activate PAR1 (Vu et al., 1991; Vassallo et al., 1992). However, unlike after administration of PAR1APs, no cell infiltration was observed after the injection of the control peptide FS-NH2. The oedema response to the partial reverse-sequence peptide was completely inhibited by compound 48/80, and was therefore likely due to activation of mast cells. It is possible that the mast cell-dependent portion of the oedema response to PAR1APs and the reverse-sequence control peptide may have been attributable to the aromatic/basic residues in these peptides. Such residues could potentially activate mast cells in a manner similar to the activation caused by compound 48/80, a formaldehyde Schiff-base conjugate of N-methyl-O-methylphenylethylamine, that can also expose mast cells to both aromatic and basic substituents. Further, the oedema response observed in previous work employing TRAP-14 may also have been due to the concurrent activation of PAR2. A recent study showed that PAR2 activation by the PAR2AP, SL-NH2 caused an increase in vascular permeability (Kawabata et al. 1998). While the ability of thrombin to activate mast cells is well established (Razin & Marx, 1984), this effect may occur independent of the activation of PAR1. It is possible that the thrombin-induced activation of mast cells may be due to the exosite peptide domains, which have previously been shown to mediate the chemotactic and mitogenic activity of thrombin (Bar-Shavit et al., 1983; Glenn et al., 1988).

A potential anti-inflammatory effect of thrombin was suggested by the observation that the oedema response it produced was consistently smaller in magnitude to what could be achieved with a selective PAR1AP. As mentioned above, such an effect was confirmed by the observation that the administration of thrombin together with the PAR1AP, Cit-NH2, resulted in a significantly attenuated oedema response. Like the pro-inflammatory effects of thrombin, the anti-inflammatory activity was abolished by pre-incubation with hirudin. These ‘anti-inflammatory' actions of thrombin may be due to its ability to activate PAR3, PAR4 or other PARs (Tay-Uyboco et al., 1995; Ishihara et al., 1997; Kahn et al., 1998; Vergnolle et al., 1998; Xu et al., 1998) that may be present in the paw tissue. Alternatively, it is possible that the ‘anti-inflammatory' effects of thrombin are due to the activity of the noncatalytic exosite peptide domains on the molecule discussed above (Bar-Shavit et al., 1983; 1984; Glenn et al., 1988; Herbert et al., 1994; Stiernberg et al., 1993, Hollenberg et al., 1996).

Our results clearly show that PAR1 activation in the rat paw displays the two main features of inflammatory process: a vascular response characterized by an oedema and granulocyte infiltration. However, the mechanism of action of the selective PAR1APs in terms of inducing oedema formation is not clear. PAR1 activation has been shown to result in the liberation of arachidonic acid and eicosanoids (Bills et al., 1977; Weksler et al., 1978; Kramer et al., 1993; Bartoli et al., 1994), which could contribute to the inflammatory response. However, the lack of an inhibitory effect of indomethacin on the oedema observed following PAR1AP administration suggests that the effect was not mediated via a prostanoid. PAR1 activation can also result in liberation of nitric oxide (Draijer et al., 1995), but pretreatment with the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, L-NAME, failed to modify the oedema response to the selective PAR1APs. Since only enzymatically active thrombin has been observed to increase vascular endothelial permeability (Malik & Fenton, 1992), and since PAR1 receptors are present on the endothelial cell (Nelkin et al., 1992), it is possible that the vascular endothelium represents the target for the PAR1APs in the paw oedema model. The endothelial cell PAR1 target for thrombin may thus play a distinct role in the overall biological effects that thrombin can cause. The two selective PAR1APs have previously been shown not to activate PAR2 (Hollenberg et al., 1997; Vergnolle et al., 1998; Kawabata et al., 1999), and PAR3 has been found to be refractory to PAR-AP activation (Ishihara et al., 1997). We cannot rule out the possibility, however, that these peptides activate either PAR4 or another, as yet unidentified PAR, such as the proteinase-activated receptor in the rat jejunum which we found to be pharmacologically distinct from PAR1, PAR2 and PAR3 (Vergnolle et al., 1998).

In conclusion, the results of the present study demonstrate that thrombin is able to exert both anti- and pro-inflammatory effects when injected into a rat hindpaw. In contrast to a previous report (Cirino et al., 1996), these studies suggest that the actions of thrombin cannot be attributed entirely to activation of PAR1. Indeed, we provide evidence that the pro-inflammatory effects of thrombin are mechanistically distinct from the pro-inflammatory effects of selective PAR1-activating peptides. Further studies are required to fully understand the mechanisms responsible for the pro- and anti-inflammatory activities of thrombin.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Dennis McMaster at the University of Calgary Peptide Synthesis Facility for provision of synthetic peptides. This work was supported by grants to Drs Hollenberg and Wallace from the Medical Research Council of Canada (MRC). Dr Vergnolle is supported by a fellowship from the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology/Abbott Laboratories/MRC. Dr Wallace is an MRC Senior Scientist and an Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research Scientist. The authors are grateful to Webb McKnight and Kevin Chapman for their assistance in performing these studies.

Abbreviations

- Cit-NH2

AparafluoroFRCyclohexylACitY-NH2

- FS-NH2

FSLLRY-NH2

- L-NAME

Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester

- PAR1

proteinase-activated receptor-1

- PAR2

proteinase-activated receptor-2

- PAR3

proteinase-activated receptor-3

- PAR4

proteinase-activated receptor-4

- PAR1APs

proteinase-activated receptor-1-activating peptides

- PARs

proteolytically-activated-receptors

- TF-NH2

TFLLR-NH2

- TRAP-14

SFLLRNPNDKYEPF

References

- BAR-SHAVIT R., KAHN A., MUDD M.S., WILNER G.D., MANN K.G., FENTON J.W. Localization of a chemotactic domain in human thrombin. Biochemistry. 1984;23:397–400. doi: 10.1021/bi00298a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAR-SHAVIT R., KAHN A., WILNER G.D., FENTON J.W. Monocyte chemotaxis: stimulation by specific exosite region in thrombin. Science. 1983;220:728–731. doi: 10.1126/science.6836310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARTOLI F., LIN H., GHOMASHCHI F., GELB M., JAIN M., APITZ-CASTRO R. Tight binding inhibition of 85-kDa phospholipase A2 but not 14-kDa phospholipase A2 inhibit release of free arachidonate in thrombin-stimulated human platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:15625–15630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BILLS T.K., SMITH J.B., SILVER M.J. Selective release of arachidonic acid from the phospholipids of human platelets in response to thrombin. J. Clin. Invest. 1977;60:1–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI108745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIZIOS R., LAI L., FENTON J.W., MALIK A.B. Thrombin-induced chemotaxis and aggregation of neutrophils. J. Cell. Physiol. 1986;128:485–490. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041280318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLACKHART B.D., EMILSSON K., NGUYEN D., TENG W., MARELLI A.J., NYSTED T.S., SUNDELIN J., SCARBOROUGH R.M. Ligand cross-reactivity within the protease-activated receptor family. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:16466–16471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIRINO G., CICALA C., BUCCI M.R., SORRENTINO L., MARAGANORE J.M., STONE S.R. Thrombin functions as an inflammatory mediator through activation of its receptor. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:821–827. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DI ROSA M., GIROUD J.P., WILLOUGHBY D.A. Studies of the mediators of the acute inflammatory response induced in rats at different sites by carrageenan and turpentine. J. Pathol. 1971;104:15–29. doi: 10.1002/path.1711040103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRAIJER R., ATSMA D.E., VAN DER LAARSE A., HINSBERGH V.W.M. cGMP and nitric oxide modulate thrombin-induced endothelial permeability: Regulation via different pathways in human aortic and umbilical vein endothelial cells. Circ. Res. 1995;76:199–208. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLENN K.C., FROST G.H., BERGMANN J.S., CARNEY D.H. Synthetic peptides bind to high-affinity thrombin receptors and modulate thrombin mitogenesis. Peptide Res. 1988;1:65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERBERT J.M., DUPUY E., LAPLACE M.C., ZINI J.M., BAR-SHAVIT R., TOBELEM G. Thrombin induces endothelial cell growth via both a proteolytic and a non-proteolytic pathway. Biochem. J. 1994;303:227–231. doi: 10.1042/bj3030227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLENBERG M.D. Protease-mediated signalling: new paradigms for cell regulation and drug development. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1996;17:3–6. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(96)81562-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLENBERG M.D., MOKASHI S., LEBLOND L., DI MAIO J. Synergistic actions of a thrombin-derived synthese peptide and a thrombin receptor-activating peptide in stimulating fibroblast mitogenesis. J.Cell. Physiol. 1996;169:491–496. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199612)169:3<491::AID-JCP9>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLENBERG M.D., SAIFEDDINE M., AL-ANI B., KAWABATA A. Proteinase-activated receptors: structural requirements for activity, receptor cross-reactivity, and receptor selectivity of receptor-activating peptides. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1997;75:832–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLENBERG M.D., YANG S.G., LANIYONU A.A., MOORE G.J., SAIFEDDINE M. Action of thrombin receptor polypeptide in gastric smooth muscle: identification of a core pentapeptide retaining full thrombin-mimetic intrinsic activity. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992;42:186–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIHARA H., CONNOLLY A.J., ZENG D., KAHN M.L., ZHENG Y.W., TIMMONS C., TRAM T., COUGHLIN S.R. Protease-activated receptor 3 is a second thrombin receptor in humans. Nature. 1997;386:502–506. doi: 10.1038/386502a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAHN M.L., ZHENG Y.W., HUANG W., BIGORNIA V., ZENG D., MOFF S., FARESE R.V., Jr, TAM C., COUGHLIN S.R. A dual thrombin receptor system for platelet activation. Nature. 1998;394:690–694. doi: 10.1038/29325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., KURODA R., MINAMI T., KATAOKA K., TANEDA M. Increased vascular permeability by a specific agonist of protease-activated receptor-2 in rat hindpaw. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:419–422. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., SAIFEDDINE M., AL-ANI B., LEBLOND L., HOLLENBERG M.D. Evaluation of proteinase-activated receptor-1 (PAR-1) agonists and antagonists using a cultured cell receptor desensitization assay: activation of PAR-2 by PAR-1 targeted ligands. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 1999;288:358–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRAMER R., ROBERTS E., MANETTA J., HYSLOP P., JAKUBOWSKI J. Thrombin-induced phosphorylation and activation of Ca2+-sensitive cytosolic phospholipase A2 in human platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:26796–26804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRANZHOFER R., CLINTON S.K., ISHII K, , COUGHLIN S.R., FENTON J.W., LIBBY P. Thrombin potently stimulates cytokine production in human vascular smooth muscle cells but not in mononuclear phagocytes. Circ. Res. 1996;79:286–294. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALIK A.B., FENTON J.W. Thrombin-mediated increase in vascular endothelial permeability. Sem. Thrombos. Hemostas. 1992;18:193–199. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1002425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARAGANORE J.M., BOURDON P., JABLONSKI J., RAMACHANDRAN K.L., FENTON J.W. Design and characterization of hirulogs: a novel class of bivalent peptide inhibitors of thrombin. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7095–7101. doi: 10.1021/bi00482a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NELKIN N.A., SOIFER S.J., O'KEEFE J., VU T.K., CHARO I.F., COUGHLIN S.R. Thrombin receptor expression in normal and atherosclerotic human arteries. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;90:1614–1621. doi: 10.1172/JCI116031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NYSTEDT S., EMILSSON K., WAHLESTEDT C., SUNDELIN J. Molecular cloning of a potential proteinase activated receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:9208–9212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RASMUSSEN U.B., VOURET-CRAVIARI V., JALLAT S., SCHLESINGER Y., PAGES G., PAVIRANI A., LECOCQ J.P., POUYSSEGUR J., VAN OBBERGHEN-SCHILLING E. cDNA cloning and expression of a hamster alpha-thrombin receptor coupled to Ca2+ mobilization. FEBS Lett. 1991;288:123–128. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAZIN E., MARX G. Thrombin-induced degranulation of cultured bone marrow-derived mast cells. J. Immunol. 1984;133:3282–3285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SKRZYPCZAK-JANKUN E., CARPEROS V.E., RAVICHANDRAN K.G, , TULINSKY A., WESTBROOK M., MARAGANORE J.M. Structure of the hirugen and hirulog 1 complexes of alpha-thrombin. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;221:1379–1393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STANKOVA J., ROLA-PLESZCZYNSKI M., D'ORLEANS-JUSTE P. Endothelin 1 and thrombin synergistically stimulate IL-6 mRNA expression and protein production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1995;26:S505–S507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STIERNBERG J., REDIN W.R., WARNER W.S., CARNEY D.H. The role of thrombin and thrombin receptor activating peptide (TRAP-508) in initiation of tissue repair. Thromb. Haemostas. 1993;70:158–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAY-UYBOCO J., POON M.C., AHMAD S., HOLLENBERG M.D. Contractile actions of thrombin receptor-derived polypeptides in human umbilical and placental vasculature: evidence for distinct receptor systems. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:569–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14970.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOOTHILL V.J., VAN MOURIK J.A., NIEWENHUIS H.K., METZELAAR M.J., PEARSON J.D. Characterization of the enhanced adhesion of neutrophil leukocytes to thrombin-stimulated endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 1990;145:283–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UENO A., MURAKAMI K., YAMANOUCHI K., WATANABE M., KONDO T. Thrombin stimulates production of interleukin-8 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Immunology. 1996;88:76–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VASSALLO R.R., KIEBER-EMMONS T., CICHOWSKI K., BRASS L.F. Structure-function relationships in the activation of platelet thrombin receptors by receptor-derived peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:6081–6085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERGNOLLE N., MACNAUGHTON W.K., AL-ANI B., SAIFEDDINE M., WALLACE J.L., HOLLENBERG M.D. Proteinase-activated receptor-2-activating peptides: identification of a receptor that regulates intestinal transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:7766–7771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VU T.K., HUNG D.T., WHEATON V.I., COUGHLIN S.R. Molecular cloning of a functional thrombin receptor reveals a novel proteolytic mechanism of receptor activation. Cell. 1991;64:1057–1068. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90261-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEKSLER B.B., LEY C.W., JAFFE E.A. Stimulation of endothelial cell prostacyclin production by thrombin, trypsin, and the ionophore A23187. J. Clin. Invest. 1978;63:923–930. doi: 10.1172/JCI109220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XU W., ANDERSEN H., WHITMORE T.E., PRESNELL S.R., YEE D.P., CHING A., GILBERT T., DAVIE E.W., FOSTER D.C. Cloning and characterization of human protease-activated receptor 4. Proc. Natl.Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:6642–6646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]