Abstract

The antinociceptive effects of the delta opioid receptor selective agonist, DPDPE [(D-Pen2,D-Pen5)-enkephalin] was studied in rats aged postnatal day (P) 14, P21, P28 and P56.

Antinociceptive effects of DPDPE were measured as percentage inhibition of the C-fibre evoked response and post-discharge of dorsal horn neurones evoked by peripheral electrical stimulation. DPDPE was administered by topical application, akin to intrathecal injection.

DPDPE (0.1–100 μg) produced dose-related inhibitions at all ages; these inhibitions were reversed by 5 μg of the opioid antagonist naloxone.

The dose-response curves for C-fibre evoked response and post-discharge of the neurones were not different in rats aged P14 and P21. DPDPE was significantly more potent at P14 and P21 compared with its inhibitory effects on these responses at P28 and P56.

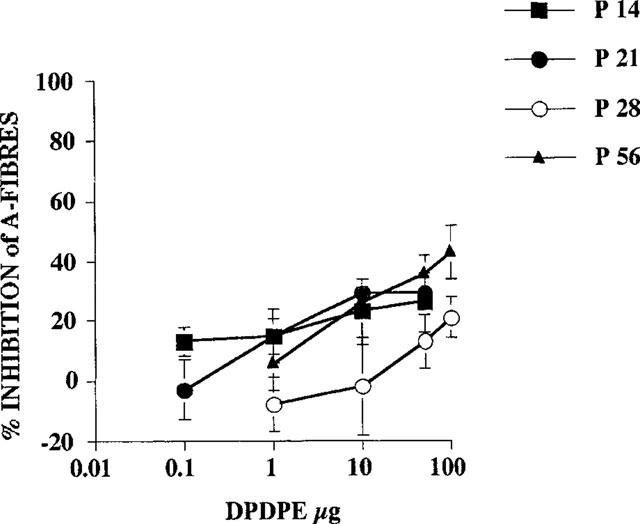

DPDPE produced minor inhibitions of the A-fibre evoked response of the neurones at P14, P21, P28 and P56, suggesting that the inhibitory effects of DPDPE are mediated via presynaptic receptors on the terminals of C-fibre afferents.

Since spinal delta opioid receptor density changes little over this period, the increased antinociceptive potency of DPDPE in the rat pups compared with the adult is likely to be due to post-receptor events, or in developmental changes in the actions of other transmitter/receptor systems within the spinal cord.

Keywords: Delta opioid receptor; development; antinociception; spinal cord; rat; DPDPE [(D-Pen2,D-Pen5)-enkephalin]

Introduction

Neonatal rat pups are capable of responding to nociceptive stimuli from very early stages (Fitzgerald, 1995) and agonists acting at opioid receptors can mediate antinociceptive effects in young rat pups where the actions of μ and κ receptor agonists have mostly been investigated (Sullivan & Dickenson, 1991; Barr 1992; Blass et al., 1993; Mclaughlin & Dewey, 1994; Oka et al., 1992; Abbott & Guy, 1995; Kitchen et al., 1995b; Tseng et al., 1995; Thornton et al., 1998).

The analgesic actions of μ, δ and κ opioid receptor agonist have been established in adult rats for many years (Duggan & North, 1984; Dickenson, 1994), but analgesia mediated by opioid agonists in the immature rat is not fully documented, and in particular, much less emphasis has been on the postnatal development of the antinociceptive actions of δ receptor agonists (Kitchen & Pinker, 1990; Crook et al., 1992; Kitchen et al., 1994; 1995a).

There is some discrepancy in the literature regarding the ontogeny of delta opioid receptors in the central nervous system of the rat. Some studies have shown δ opioid receptors to be present in the brain and spinal cord from very early postnatal ages (Attali et al., 1990; Xia & Haddad, 1991; Kitchen et al., 1995b). However, other studies could not detect delta receptor binding before the second postnatal week (McDowell & Kitchen, 1986). Generally the density of delta receptor binding sites increases after their first appearance towards adult levels (McDowell & Kitchen, 1986; Spain et al., 1985; Petrillo et al., 1987; Xia & Haddad, 1991; Kitchen et al., 1995b). We have previously reported that there is little change in the density of delta receptor binding sites in the rat spinal cord during postnatal development, where delta receptor binding was first detected at P7 (Rahman et al., 1998). A similar lack of marked postnatal change in the density of delta receptor binding sites in the spinal cord was also reported (Attali et al., 1990). Spinal morphine has been shown to produce more potent antinociceptive effects in young animals and although there is generally a greater density of opioid receptors in early life (Spain et al., 1985; Petrillo et al., 1987; Attali et al., 1990; Xia & Haddad, 1991; Rahman et al., 1998) the two do not correlate. Thus, while studies on the density of receptors in the spinal cord during the postnatal period provide information on the development of opioid systems it is not always possible to predict the functional effect of agonists at opioid receptors simply from number of receptor binding sites (Rahman et al., 1998).

In the present study we have tested the effects of spinal DPDPE [(D-Pen2,D-Pen5)-enkephalin] on electrically evoked dorsal horn neuronal responses in anaesthetized rats aged postnatal day (P) 14, P21, P28 and P56 (adult) to provide information on the functional development of delta opioid receptor mediated antinociception at the spinal cord. DPDPE is a highly selective delta opioid receptor agonist with low affinity for μ opioid receptor binding sites (Clarke et al., 1986) and has been shown to produce analgesia via spinal and supraspinal receptors (Zaki et al., 1996). The inhibitory effects of DPDPE on noxious evoked responses of dorsal horn neurones in young rats has not previously been compared to its effects on neurones in the adult.

This study was not carried out on pups younger than 14 days since clear and stable C-fibre evoked action potentials are relatively rare in the first 2 postnatal weeks (Fitzgerald, 1997).

In this study the primary afferents are directly activated by electrical stimulation so variables such as postnatal changes in surface area and thickness of the hind paw will not influence the degree of C-fibre activation. Direct C-fibre activation at three times the threshold allowed a standard stimulus across the age groups. The blood brain barrier continues to develop postnatally and is not fully mature until postnatal day 30, (Keep et al., 1986) and the pharmacokinetics of opiates also alter with increasing age. Administration of DPDPE directly onto the lumbar spinal cord eliminates these as possible confounding factors.

Methods

Electrophysiological recordings of spinal neurones

Recordings were made from single neurones within the deep dorsal horn of the spinal cords of anaesthetized male Sprague-Dawley rats at P14, P21, P28 and P56 (adult). Neuronal recording in the adult animals was carried out under halothane anaesthesia (2%) in a gaseous mixture of 66% N2O and 33% O2 via a tracheal cannula. Due to their small size, neuronal recording in the pups at days P14, P21 and P28 was carried out under urethane anaesthesia given by intraperitoneal (i.p.) Injection (1.75 g kg−1). Halothane and urethane anaesthesia have been compared previously in the adult rat and no differences in neuronal activity or neuronal responses to opioids were observed (Smallman et al., 1989). Complete areflexia and surgical anaesthesia was sufficiently maintained for the duration of the experiment without any obvious depression of respiratory or other physiological functions.

The rats were held in a stereotaxic frame and a laminectomy performed such that the L3-L5 section of the cord was exposed. The cord was held rigidly with clamps positioned rostral and caudal to the exposed area. A parylene coated tungsten electrode was lowered into the dorsal horn of the spinal cord in 10 μm steps using a SCAT microdrive. This allowed the measurement of the depth of the neuronal recording relative to the surface of the dorsal horn.

Single unit extracellular recordings were made of convergent neurones, characterized by their response to touch (innocuous) and pinch (noxious) stimulation of the peripheral receptive field. The neurones were then characterized by their response to transcutaneous electrical stimulation (2 ms wide pulse, 0.5 Hz) via two needles inserted into the peripheral receptive field of the neurone.

Trials, consisting of a train of 16 electrical pulses, at three times the threshold for activation of the C-fibre response of the neurone, were applied every 10 min. The electrically evoked response of the neurone was captured and displayed as a post stimulus histogram (PSTH), by means of a 1401 interface (Cambridge Electronic Design, U.K.) and MRATE software. This allowed the quantification of the action potentials with respect to latency of evoked response. In the adult, A- and C-fibre inputs were separated with respect to latency (A-fibres=0–90 ms, C-fibres=90–300 ms, and post discharge=300–800 ms) and threshold. The threshold for activation of the C-fibre evoked response was the stimulus required to first evoke a long latency spike from the dorsal horn neurone. Recording from convergent neurones in rat pups was essentially as described for the adult rats. Adjustments were made for the latencies of the A- and C-fibres bands based on the size of the animal and the clearly separable peaks on the PSTH. A-fibre evoked responses were measured from 0–50 ms, C-fibre evoked responses from 50–250 ms and post discharge from 250–800 ms following a train of 16 electrical stimuli. A number of neurones were recorded in each rat at each postnatal age, but the pharmacology was performed on only one neurone per rat at each age.

Following at least three stable control responses, the variance of the C-fibre evoked response of the neurone never being greater than 10%, a cumulative dose response of the effects of topically applied DPDPE (0.1–100 μg–50 μl) onto the spinal cord, akin to intrathecal injection, on the neuronal responses was obtained. Tests were carried out every 10 min after each drug dose application and the effects of each dose was followed for 40 min. After the inhibitory effects of the highest dose of DPDPE had been evaluated, naloxone (5 μg) was applied spinally and the reversal of the effects of the delta opioid was followed for another 40 min. In another series of experiments, naltrindole, the selective delta opioid receptor antagonist, at a dose of 50 μg, was given spinally 20 min before 50 μg of DPDPE. In addition a further series of experiments were performed, where naltrindole (50 μg) was given spinally 20 min before 2.5 μg morphine. The effects of morphine were followed for 40 min and subsequently 1 μg naloxone was given spinally.

The results were calculated as percentage changes from control responses for each neurone and the overall results for each dose were expressed as means±s.e.mean.

Drugs and statistical procedures

(D-Pen2,D-Pen5)-enkephalin (DPDPE) was purchased from Bachem, naltrindole and naloxone from Sigma (U.K.). At each age, multiple paired Student's t-tests were performed comparing the effects of each dose of DPDPE to the control C- and A-fibre evoked response and the post-discharge of the neurones using the Bonferroni correction. To compare the relative potency of DPDPE at each postnatal age the effective dose to produce a 50% inhibition of the control response, (ED50 values) for the effect of DPDPE on the evoked neuronal responses at each postnatal age were derived using a curve fitting program (Inplot). A Student's t-test (two-tailed: unpaired) was then used to compare the relative potencies of DPDPE at the different ages. A one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Student's- Newmans-Keuls post-hoc tests was performed to compare the C-fibre thresholds and the evoked neuronal responses across the ages. A non-parametric t-test (two-tailed: unpaired) was used to compare the effects of DPDPE or morphine alone on the C-fibre evoked response with their effects in the presence of naltrindole. In all cases P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Age related changes in neuronal responses

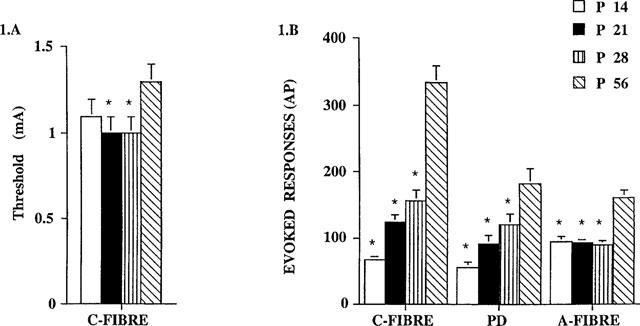

Significant age-related differences were observed such that the evoked responses of the neurones increased with the age of the animal, so that : C-fibre evoked response: P14<P21= P28<P56; post-discharge: P14=P21=P28<P56; A-fibre evoked response: P14=P21=P28<P56. The magnitude of the C-fibre evoked responses and the post-discharge of the dorsal horn neurones at P14 were significantly less than those at P21, P28 and P56, although there was no significant difference in the C-fibre threshold at P14 compared with each of the other age groups.

The electrically evoked neuronal responses of the dorsal horn neurones at P21 and P28 did not differ, but at both these ages the C-fibre thresholds, A- and C-fibre evoked responses and the post-discharge of the dorsal horn neurones were significantly lower compared with those at P56 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Evoked neuronal responses of convergent dorsal horn neurones in rats at P14, P21, P28 and P56. (A) The thresholds (mA) for the C-fibre evoked responses with age. ANOVA analysis showed there was an overall significant variation with age, F3,131=3.748; P=0.013, P21 and P28 thresholds were significantly different in comparison with P56 threshold (*P<0.05), Student-Newmans-Keuls post-hoc test. (B) The neuronal responses evoked by the train of stimuli, expressed as action potentials (AP), for the C-fibre, post-discharge and A-fibre evoked responses. ANOVA analysis showed there was an overall significant variation with age for: C-fibres, F3,131=40.34, P<0.0001; PD, F3,131=7.92, P<0.0001; A-fibres, F3,131=16.6, P<0.0001. P14, P21 and P28 responses were significantly different in comparison with responses at P56 (*P<0.05), Student-Newmans-Keuls post-hoc test. n=23 at P14, n=35 at P21, n=22 at P28, n=43 at P56. Values are mean±s.e.mean.

Antinociceptive effects of DPDPE

The antinociceptive action of spinal DPDPE (0.1, 1, 10, 50 and 100 μg) on these evoked responses in rats at these different postnatal ages was investigated. Clear age-related differences were observed in the potency of DPDPE on the C-fibre evoked response and the post-discharge of the dorsal horn neurones.

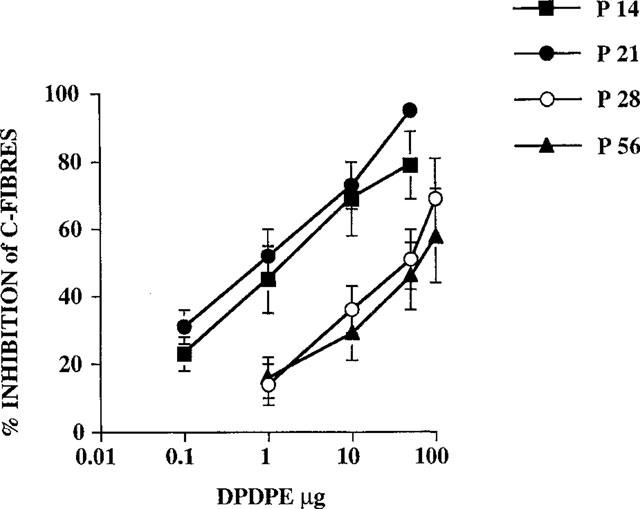

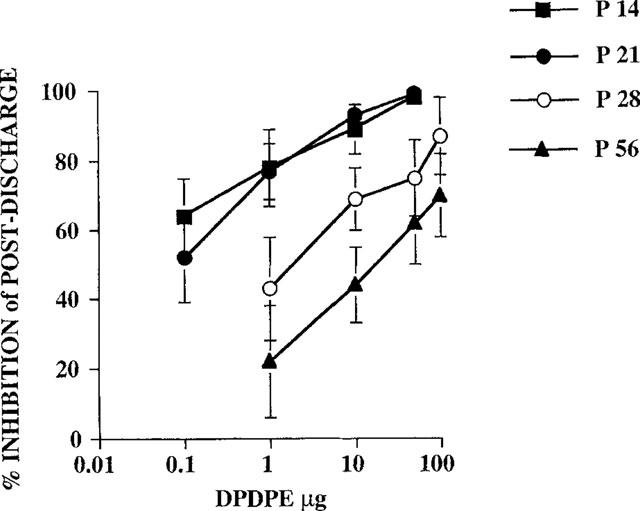

At each age studied, DPDPE inhibited the C-fibre evoked response and the post-discharge of the dorsal horn neurones in a dose related manner (Figures 2 and 3). DPDPE produced little inhibition of the A-fibre evoked responses of the neurones at any age and any inhibition seen was only with the highest doses (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Dose response curves showing the inhibitory effects of DPDPE on the C-fibre evoked response at different postnatal ages; P14, P21, P28 and P56 (adult). Comparison of derived ED50 values indicate that DPDPE was more potent at the earlier postnatal ages compared with P28 and adult (see results). The order of potency was: P14=P21>P28=P56 (n=6–8 for each dose at each postnatal age).

Figure 3.

Dose-related inhibitions of the post-discharge of convergent neurones were produced by topical application of DPDPE (μg) in rats at P14, P21, P28 and P56 (adult). The potency order for spinal DPDPE was as follows: P14=P21>P28>P56 (n=6–8 for each dose at each postnatal age).

Figure 4.

Dose response curves for the inhibition of A-fibre evoked responses by spinal application of DPDPE on dorsal horn neurones at different postnatal ages (n=6–8 for each dose at each postnatal age).

Spinal application of DPDPE inhibited the C-fibre evoked responses of the dorsal horn neurones at P14 (ED50 =1.8±0.4) and P21 (ED50=0.9±0.3) to a similar extent Students t-test, P>0.05.

The potency of DPDPE declined at later ages. By P28, DPDPE was less potent at inhibiting the C-fibre evoked response of the dorsal horn neurones (ED50=29±8) compared with P14 and P21. No further decrease in potency was observed at P56, with the dose response curves of spinal DPDPE on the C-fibre evoked response of dorsal horn neurones at P56 (ED50=47±16) being similar to that at P28 (Figure 2).

The dose response curves for the inhibition of the post-discharge of dorsal horn neurones at P14 (ED50=0.05±0.03) and P21 (ED50=0.09±0.01) were again similar, with all doses producing a significant reduction compared to control. Again a similar pattern was seen so that at P28 DPDPE was less potent than at P14 and P21 although the potency (ED50=2±0.7) was still greater than at P56 (ED50=16±4) (Figure 3).

All doses tested produced a significant reduction in the C-fibre evoked response and post-discharge of the neurones at P14 and P21, except for 1 μg of DPDPE on the post-discharge of the neurones at P21 (Figures 2 and 3). At P56, doses of 10, 50 and 100 μg of DPDPE produced significant inhibitions of the C-fibre evoked response, whereas only the highest two doses of DPDPE (50 and 100 μg) produced a significant reduction of the C-fibre evoked response at P28. The post-discharge of the neurones was significantly inhibited by 10, 50 and 100 μg of DPDPE at P28 and P56 (Figure 3).

DPDPE did not produce any significant inhibitions of the A-fibre evoked response of the neurones in rats at P14. DPDPE at 10 and 50 μg, produced small but significant reductions of the A-fibre evoked response of the neurones at P21 (maximum inhibition 29%) yet only the top dose tested (100 μg) produced a significant reduction (21%) of the A-fibre evoked response of the neurones in rats at P28. By P56, slightly greater inhibitions of the A-fibre evoked response of the neurones were observed, with 10, 50 and 100 μg producing significant reductions, 26, 36 and 43% respectively, of control responses (Figure 4). Paired Student's t-test with Bonferroni corrected P-values were used to test for significance.

Antagonism of the effects of DPDPE

The opioid antagonist naloxone (5 μg) reversed the inhibitory effects of DPDPE on the evoked neuronal responses back to control values at all the ages studied. For example, naloxone reversed the maximum DPDPE mediated inhibition of the C-fibre evoked response at P14, P21, P28 and P56 (see Figure 1) to 92±21, 87±9, 101±7 and 84±4% of control values respectively (n=3–8).

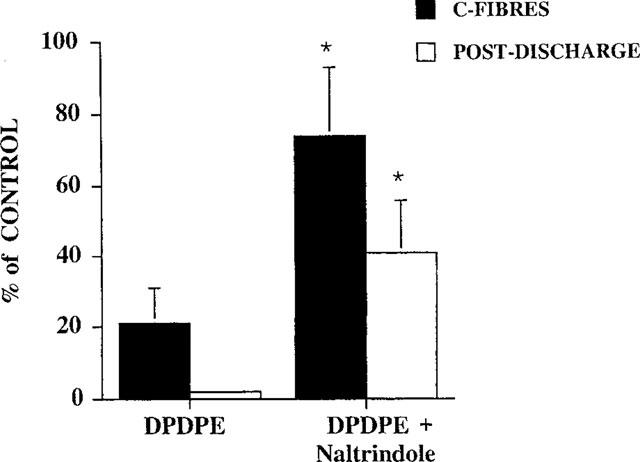

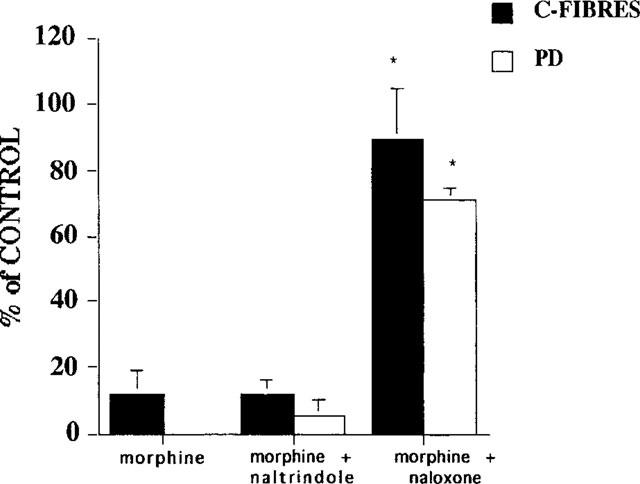

The selective δ opioid antagonist naltrindole significantly attenuated the inhibitory effects of DPDPE (50 μg) on the C-fibre evoked response and the post-discharge of neurones recorded at P14 (n=5). Thus the maximum inhibition of the C-fibre evoked response in the presence of naltrindole (50 μg) was 26±19% compared to 79±10% with DPDPE alone (Figure 5). The same dose of naltrindole (50 μg) did not significantly antagonize (P>0.05) the inhibitory effects of an equieffective dose of morphine (2.5 μg) on the C-fibre evoked response or post-discharge of the neurones in P14 pups (n=4). The inhibition of the C-fibre evoked response produced by morphine in the presence of naltrondole was 88±4%, identical to that reported previously in P14 rat pups (Rahman et al., 1998). These inhibitory effects of morphine were subsequently reversed back to control values by 1 μg naloxone (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Antagonism of DPDPE (50 μg) effects on the C-fibre evoked response and post-discharge of the neurones by the selective δ receptor antagonist naltrindole (50 μg). *P<0.05, Mann-Whitney t-test.

Figure 6.

The effect of morphine (2.5 μg) in the presence of the selective δ receptor antagonist naltrindole (50 μg) was unchanged (n=4). The inhibition of the C-fibre evoked response and post-discharge of dorsal horn neurones in P14 rat pups was identical to that previously reported for morphine alone (Rahman et al., 1998). Naloxone (1 μg) significantly reversed the inhibitory effects of morphine produced in the presence of naltrindole (50 μg). *P<0.05, Mann-Whitney t-test.

Discussion

The neonatal nervous system is not simply an immature version of the adult nervous system, but proceeds through a number of transitory functional stages before reaching the adult profile (Fitzgerald, 1997). Due to the anatomical, physiological and pharmacological changes that continue to occur for a number of weeks postnatally, the transmission and modulation of nociceptive information is not the same as that of the fully mature CNS and so the antinociceptive effects of opioids could predictably be different in the rat pup. A number of studies have shown different ontological and developmental changes in opioid receptors where higher receptor densities in early life have been reported in some studies (McDowell & Kitchen, 1986; Petrillo et al., 1987; Attali et al., 1990; Xia & Haddad, 1991; Kitchen et al., 1992; Kar & Quirion, 1995; Rahman et al., 1998). It can be noted however, that these results may arise from the method of expression of receptor density (weight of the neonatal tissue versus protein content). Although a number of functional studies support the premise that opioid effects are different in the rat pup (Barr, 1992; Jackson & Kitchen, 1989; Kitchen et al., 1995a; Marsh et al., 1998) there have been few direct comparisons of the actions of opioids in the pup with the adult (McLaughlin & Dewey, 1994, Sullivan & Dickenson, 1991; Rahman et al., 1998).

The magnitude of the evoked A-fibre, C-fibre response and the post-discharge of dorsal horn neurones varied with postnatal age. In general the magnitude of the C-fibre evoked responses and post-discharge of the neurones increased with increasing age, with the exception of the A-fibre evoked neuronal response, which was only greater at P56. Even at 28 days, the activity of dorsal horn neurones, at least in response to peripheral electrical stimulation, was significantly lower compared with the evoked responses of neurones in adult rats. This suggests that the neurophysiology of the rat central nervous system is not fully mature until some time after 4 weeks postnatally.

The threshold for activation of the C-fibre evoked response varied little across the postnatal ages, although the C-fibre thresholds at P21 and P28 were significantly lower compared with the threshold at P56. This suggests that C-fibre transmission from afferents to dorsal horn neurones is secure at all ages used in this study.

Large scale cell death takes place in the dorsal root ganglia at very early stages in development, so that the number of surviving cells are not different at P10, P15 and adult (Coggeshall et al., 1994). There is a postnatal loss of axons in the rat sciatic nerve (Jenq et al., 1986) with the number of unmyelinated axons decreasing from about 19,000 to 14,000 between postnatal day 14 and adulthood. Thus it is unlikely that the smaller evoked responses of the neurones seen in the rat pups are due to the number of unmyelinated axons terminating in the dorsal horn. Reduced conduction in unmyelinated axons is also not a factor, as dorsal root volley recordings in neonates show that these axons have the ability to conduct well (Fitzgerald & Gibson, 1984) and anatomical studies of the development of myelination agree with this (Friede & Samaorajski, 1968). It is probable then that the age differences in the evoked neuronal response are not related to the activity of the C-fibre primary afferents but more likely to be due to modifications within the spinal cord. Not only are there changes in excitatory amino-acid and peptide receptors with development but interneurones in the substantia gelatinosa do not mature until well after birth, and dendritic branching continues until at least 3 weeks postnatally (Bicknell & Beal, 1984; Fitzgerald, 1997). This raises the possibility that while the synaptic links between the C-fibre primary afferent and the dorsal horn neurone are sufficient to produce a single electrically evoked C-fibre response of the neurone at each of the postnatal ages studied, at three times C-fibre threshold the immaturity of the interneurones may lead to fewer evoked neuronal responses of the dorsal horn neurones at P14, P21 and P28.

The results of the present study show that DPDPE produces significant antinociceptive effects via spinal delta receptors at all the postnatal ages studied. DPDPE was applied topically to the spinal cord, so that factors such as changes in the blood brain barrier and pharmacokinetics are unlikely to underlie the differences observed in the potency of DPDPE on the C-fibre evoked responses and post-discharge of the neurones at the different postnatal ages.

The inhibitory effects of DPDPE were greatest on the C-fibre evoked response and post-discharge of the neurones compared with inhibition of the A-fibre evoked response, suggesting DPDPE is more selective for inhibition of nociceptive transmission at all stages. In contrast to the findings of this study it has been reported that intraperitoneal (i.p.) DPDPE does not produce any behavioural effects in 5, 10 and 20 day old rat pups. In a tail immersion test a number of delta agonists (i.p.) failed to produce antinociceptive effects (Jackson & Kitchen, 1989; Kitchen et al., 1995a). It is possible that the delta agonists given by intraperitoneal injection failed to reach spinal delta receptors, at least in sufficient amounts, even though the blood brain barrier is not fully mature until P30 (Keep et al., 1986). In support of our findings with direct CNS application of the opioid, delta mediated effects have been reported with intracisternal DPDPE in P10 and P14 rat pups (Carden et al., 1991), and epidural DPDPE has been shown to increase the Von Frey threshold for withdrawal reflex in pups as young as P3 (Marsh et al., 1997; 1998). Certainly the antinociceptive effects of spinal DPDPE we report are opioid receptor mediated as naloxone significantly reversed the maximum inhibitions of DPDPE at each age. Naltrindole, a delta receptor selective antagonist, also significantly attenuated the inhibitory effects of the highest dose of DPDPE on the C-fibre evoked responses at P14. It is unlikely that naltrindole was acting at μ opioid receptors as morphine was still able to produce maximal inhibitions of the C-fibre evoked response and post-discharge of dorsal horn neurones in P14 pups in the presence of the antagonist. Therefore this study shows that DPDPE produces significant antinociceptive effects via spinal delta receptors, but one cannot entirely rule out some residual action on spinal μ receptors as naltrindole did not fully prevent the inhibitory action of DPDPE on the post-discharge of the neurones.

Although little effect was observed on A-fibre evoked response of the neurones, with increasing postnatal age generally greater inhibitions of the A-fibre evoked response were observed. Inhibition of A-fibre evoked response is likely to be a post-synaptic receptor mediated event since Aβ-fibres themselves do not contain opioid receptors (Ninkovic et al., 1982). Therefore it is conceivable that either the proportion of functional postsynaptic δ receptors increases with age, or that A-delta fibres, likely to possess δ receptors, may increasingly converge onto those neurones recorded from at the later postnatal ages.

Although the dose reponse curve for DPDPE on the C-fibre evoked response of the dorsal horn neurones at P28 is the same as that at P56, the dose-response curve for the inhibition of the post-discharge of the neurones at P28 was to the left of that for the adult. This would suggest that the maturational changes in the neuropharmacology of the cord that influence the ability of DPDPE to inhibit neuronal responses probably only achieve the adult state after postnatal day 28.

As the actual number of action potentials produced in the dorsal horn neurones by peripheral C-fibre activation at P14 and P21 were significantly lower than the evoked responses at P56, it could be proposed that delta opioid receptor activation by DPDPE could prevent depolarization of the dorsal horn neurone more easily as the overall activity in the spinal cord at these ages is less compared with the adult. Differences in the magnitude of the evoked neuronal responses of the dorsal horn neurones are unlikely to underlie the age related differential effects of DPDPE. The C-fibre evoked response and post-discharge of the neurones at P14 are significantly lower than at P21 yet the dose response curves overlie each other. Similarly, the dose response curves for C-fibre inhibition by DPDPE were the same at P28 as at P56, although the evoked responses at P56 are significantly greater than at P28. The converse is also true, in that the evoked responses at P21 and P28 are not significantly different, yet the dose response curves for the inhibition of C-fibre evoked response and post-discharge of the neurones are different. In addition a study in adult rats has shown that there is no correlation between the magnitude of the C-fibre evoked response of dorsal horn neurones and the antinociceptive potency of morphine (Stanfa et al., 1992).

The increased sensitivity of dorsal horn neurones to spinal DPDPE in the rat pups seen in the present study does not correlate with the density of delta receptors in the spinal cord. There is little change in the density of delta receptors in the spinal cord during pre- and postnatal development (Attali et al., 1990; Rahman et al., 1998). We have also previously reported no direct correlation between the density of mu opioid receptor binding sites in the spinal cord and functional effects of spinal morphine at different postnatal ages (Rahman et al., 1998). As the antinociceptive effects of opioid receptor agonists are not entirely predictable from the density of receptor binding sites, this suggests that a number of the receptors labelled in the spinal cord are not functional. Indeed immunohistochemical studies with antibodies to the δ opioid receptor (DOR-1), have reported DOR like immunoreactivity at intracellular sites (Cheng et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 1998), as have studies where μ and δ opioid receptor binding in membranes from endoplasmic reticulum and golgi complexes were investigated. These studies concluded that these opioid receptors were not functionally coupled to G-proteins (Suzcs & Coscia, 1992).

While the affinity of DPDPE for the delta receptor remains constant during development, (McDowell & Kitchen, 1986), G-protein coupling and effector mechanisms may be developmentally regulated. The data from our study would indicate a greater efficacy of DPDPE at its receptor in P14 and P21 day rats, and so possibly stronger coupling to G-proteins. However, DPDPE specific binding is inhibited by Gpp(NH)p to a similar extent in P5 and adult rat membranes, yet a 5 fold increase in basal GTPase activity of the α-subunit of G-proteins between P5 and adulthood has been reported, it can be concluded that there is little difference in G-protein coupling but a much greater activity of G-proteins in adulthood compared with P5 (Szucs & Coscia, 1990). Milligan et al. (1987) reported that the levels of G1 and G0 are present in 100–1000 fold excess over the amount of μ and δ receptors in the brain of neonatal and adult rats. In addition, increased morphine antinociception in neonatal rats at P10 has been observed despite reported weaker G-protein-receptor coupling than at P27 (Windh & Kuhn, 1995). The findings from these studies would indicate that both levels and coupling of G-proteins in development are not responsible for the increased inhibitory effects of DPDPE seen in our study.

The interactions between activity in afferent fibres and spinal cord neurones is the net result of evoked and tonic activity in a number of excitatory and inhibitory transmitter systems. The interplay between these receptors will determine the level of excitation in spinal nociceptive transmission (Dickenson, 1995). Consequently, it cannot be ruled out that developmental changes in antinociceptive potency of DPDPE may be due to postnatal differences in the modulation of nociceptive transmission by the activity of pharmacological and physiological systems intrinsic to the cord or via descending controls.

Since the advent of specific delta receptor agonists and antagonists a number of studies have shown the existence of delta receptor subtypes, δ1 and δ2, although molecular biological cloning studies have only identified a single cDNA encoding one delta receptor, DOR-1. DPDPE is thought to exert its antinociceptive effects primarily via the δ1 receptor subtype in the rat spinal cord (Stewart & Hammond, 1993). However, it has been reported, depending on the type of noxious stimuli, that DPDPE also has some efficacy at δ2 receptors in the rat spinal cord (Stewart & Hammond, 1993). Behavioural studies investigating the postnatal development of delta receptor mediated antinociception also support the existence of delta receptor heterogeneity. These studies also suggest that the two delta receptor subtypes develop independently (Crook et al., 1992; Kitchen et al., 1994; Kitchen & Pinker, 1990). The process of weaning has been shown to be the trigger stimulus for the functional expression of the δ2 receptor subtype (Kitchen et al., 1994; 1995b). In our study, DPDPE produced near maximum inhibitions of the noxious evoked response of neurones in P14 rat pups (pre-weaning) and P21 (post-weaning) with similar dose-response curves. Weaning of the pups took place at postnatal day 20. Further changes were seen at P21 compared with P28, even though these rats were weaned. The inhibitory effects of δ1 receptors have been shown not to be regulated developmentally by the weaning process (Kitchen et al., 1994), and as DPDPE is selective for the δ1 receptor subtype (Stewart & Hammond, 1993), it seems unlikely that the differential inhibitory effects of DPDPE seen at the various postnatal ages are related to weaning, although without non-weaned controls it is not possible to rule out this factor.

Our findings with DPDPE agree with the view that young rats have an increased sensitivity to opioids compared to adults (Barr, 1992; McLaughlin & Dewey, 1994; Sullivan & Dickenson, 1991; Rahman et al., 1998). Spinal DPDPE, probably acting via presynaptic delta receptors on C-fibre afferents, was clearly more potent on the noxious evoked responses in the pups compared with the adult. The differential age-related effects of spinal DPDPE likely relate to events intrinsic to spinal cord neuronal systems and further emphasize the developmental plasticity of opioid controls.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Medical Research Council and EEC Biomed II (BMH4-CT95-0172).

Abbreviations

- DPDPE

[(D-Pen2,D-Pen5)-enkephalin]

- ED50

Effective dose to produce a 50 % inhibition of the control response

- Gpp(NH)p

5′guanylylimidodiphosphate

- G-protein

guanine nucleotide regulatory protein

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- P

postnatal day

References

- ABBOTT F.V., GUY E.R. Effects of morphine, pentobarbital and amphetamine on formalin-induced behaviours in infant rats: sedation versus specific suppression of pain. Pain. 1995;62:303–312. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00277-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATTALI B., SAYA D., VOGEL Z. Pre- and postnatal development of opioid receptor subtypes in rat spinal cord. Dev. Brain Res. 1990;53:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90128-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARR G.A.Behavioural effects of opiates during development Development of the central nervous system: Effects of alcohol and opiates 1992New York: Wiley-Liss; 221–254.ed. Miller, M.W. pp [Google Scholar]

- BICKNELL H.R., BEAL J.A. Aconal and dendritic development of substantia gelatinosa neurones in the lumbosacral spinal cord of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1984;226:508–522. doi: 10.1002/cne.902260406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLASS E.M., CRAMER C.P., FANSELOW M.S. The development of morphine-induced antinociception in neonatal rats : a comparison of forepaw, hindpaw, and tail retraction from a thermal stimulus. Pharm. Biochem Behav. 1993;44:643–649. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARDEN S.E., BARR G.A., HOFER M.A. Differential effects of specific opioid receptor agonists on rat pup calls. Dev. Brain. Res. 1991;62:17–22. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90185-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENG P.Y., SVINGOS A.L., WANG H., CLARKE C.L., JENAB S., BECZKOWSKA I.W., INTURRISI C.E., PICKEL V.M. Ultrastructural immunolabelling shows prominent presynaptic vesicular localization of δ-opioid receptor within both enkephalin- and nonenkephalin-containing axon terminals in the superficial layers of the rat cervical cord. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:5976–5988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-05976.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARK J.A., ITZAHAK Y., HRUBY V.J., YAMAMURA H.I., PASTERNAK G.W. [D-Pen2-D-Pen5] enkephalin (DPDPE): a selective enkephalin with low affinity for the μ1 opiate binding sites. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1986;128:303–304. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90784-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COGGESHALL R.E., POVER C.M., FITZGERALD M. Dorsal root ganglion cell death and surviving cell numbers in relation to the development of sensory innervation in the rat hindlimb. Dev. Brain Res. 1994;82:193–212. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)90163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROOK T.J., KITCHEN I., HILL R.G. Effects of the δ-opioid receptor antagonist naltrindole on anti-nociceptive responses to selective δ-agonists in postweanling rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;107:573–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb12785.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DICKENSON A.H.Where and how do opioids act Proceedings of the 7th World congress in pain, Progress in Pain Research and Management 19942Seattle: IASP Press; 525–552.eds. Gebhart, G.F., Hammond, D.L. & Jensen, T.S. [Google Scholar]

- DICKENSON A.H. Spinal cord pharmacology of pain. Br. J. Anaesthesia. 1995;75:193–200. doi: 10.1093/bja/75.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUGGAN A.W., NORTH R.A. Electrophysiology of opioids. Pharmacol. Rev. 1984;35:219–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FITZGERALD M. Pain in infancy: Some unanswered questions. Pain reviews. 1995;2:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- FITZGERALD M.Neonatal pharmacology of pain Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology: The Pharmacology of Pain 1997Berlin Heidelberg: Springer- Verlag; 447–460.eds. Dickenson, A. & Besson, J.-M. pp [Google Scholar]

- FITZGERALD M., GIBSON S.J. The postnatal physiological and neurochemical development of peripheral sensory C-fibres. Neurosci. 1984;13:933–944. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRIEDE R.L., SAMAORAJSKI T. Myelin formation in the sciatic nerve of the rat. A quantitative electron microscopic, histochemical and radioautographic study. J. Neuropath. Neurol. 1968;27:546–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JACKSON H.C., KITCHEN I. Behavioural effects of selective μ-, κ- and δ-opioid agonists in neonatal rats. Psychopharmacol. 1989;97:404–409. doi: 10.1007/BF00439459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JENQ C.-B., CHUNG K., COGGESHALL R.E. Postnatal loss of axons in normal rat sciatic nerve. J. Comp. Neurol. 1986;244:445–450. doi: 10.1002/cne.902440404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAR S., QUIRION R. Neuropeptide receptors in developing and adult rat spinal cord: an in vitro quantitative autoradiography study of calcitonin gene-related peptide, neurokinins, μ-opioid, galanin, somatostatin, neurotensin, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide receptors. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;354:253–281. doi: 10.1002/cne.903540208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEEP R.F., CAWKWELL R.D., JONES H.C.The development of the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier: the relationship between structure and function in the rat choroid plexus The Blood-Brain Barrier in Health and Disease 1986Chichester: Ellis Horwood; 41–51.eds. Suckling, A.J., Rumsby, M.G. & Bradbury, M.W.B. pp [Google Scholar]

- KITCHEN I., CROOK T.J., MUHAMMAD B.Y., HILL R.G. Evidence that weaning stimulates the developmental expression of a δ-opioid receptor subtype in the rat. Dev. Brain Res. 1994;78:147–150. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITCHEN I., KELLY M.D.W., DECABO C. κ- and δ opioid receptor mediated antinociception in preweanling rats. Analgesia. 1995a;1:512–515. [Google Scholar]

- KITCHEN I., KELLY M., HUNTER J.C. Ontogenetic studies with [3H]-CI-977 reveal early development of κ-opioid sites in rat brain. Mol. Neuropharmacol. 1992;2:269–272. [Google Scholar]

- KITCHEN I., LESLIE M., KELLY M., BARNES R., CROOK T.J., HILL R.G., BORSODI A., TOTH G., MELCHIORRI P., NEGRI L. Development of delta-opioid receotor subtypes and the regulatory role of weaning: radioligand binding, autoradiography and in situ hybridization studies. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995b;275:1597–1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITCHEN I., PINKER S.R. Antagonism of swim-stress-induced antinociception by the delta-opioid receptor antagonist naltrindole in adult and young rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1990;100:685–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARSH D.F., DICKENSON A.H., HATCH D.J., FITZGERALD M. The development of opioid analgesia to carrageenan-induced inflammation 1997136Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Pediatric Pain, pp

- MARSH D.F., DICKENSON A.H., HATCH D.J., FITZGERALD M.Epidural opioid analgesia in infant rats I: mechanical and heat responses Pain 1998. in press [DOI] [PubMed]

- MCDOWELL J., KITCHEN I. Development of opioid systems: peptides, receptors and pharmacology. Brain Res. 1986;12:397–421. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(87)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLAUGHLIN C.R., DEWEY W.L. A comparison of the antinociceptive effects of opioid agonists in neonatal and adult rats in phasic and tonic nociceptive tests. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1994;49:1017–1023. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLIGAN G., STREATY R.A., GIERSCHIK P., SPIEGEL A.M., KLEE W.A. Development of opioid receptors and GTP-binding regulatory proteins in neonatal rat brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:8626–8630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NINKOVIC M., HUNT S.P., GLEAVE J.R.W. Localization of opiate and histamine H2- receptors in the primate sensory ganglia and spinal cord. Brain Res. 1982;241:197–206. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)91056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKA T., LIU X.-F., KAJITA T., OHGYIA N., GHODA K., TANIGUCHI T., ARAI Y., MATSUMIYA T. Effects of the subcutaneous administration of enkephalins on tail-flick response and righting reflex of developing rats. Dev. Brain Res. 1992;69:271–276. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(92)90167-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETRILLO P., TAVANI A., VEROTTA D., ROBSON L.E., KOSTERLITZ H.W. Differential postnatal development of μ-, δ- and κ- opioid binding sites in rat brain. Dev. Brain. Res. 1987;31:53–58. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(87)90082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAHMAN W., DASHWOOD M.R., FITZGERALD M., AYNSLEY-GREEN A., DICKENSON A.H. Postnatal development of multiple opioid receptors in the spinal cord and development of spinal morphine analgesia. Dev. Brain Res. 1998;108:239–254. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMALLMAN K., DICKENSON A.H., HALSEY M.J. Electrophysiological studies on the effects of opiates on dorsal horn nociceptive neurones at 51 atmospheres absolute. Pain. 1989;38:57–64. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90073-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPAIN J.W., ROTH B.L., COSICA C.J. Differential ontogeny of multiple opioid receptors (μ, δ and κ) J. Neuroscience. 1985;5:584–588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-03-00584.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STANFA L.C., SULLIVAN A.F., DICKENSON A.H. Alterations in neuronal excitability and the potency of spinal mu, delta and kappa opioids after carrageenan-induced inflammation. Pain. 1992;50:345–354. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90040-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEWART P.E., HAMMOND D.L. Evidence for delta opioid receptor subtypes in rat spinal cord: studies with intrathecal naltriben, cyclic [D-Pen2,D-Pen5] enkephalin and [D-Ala2,Glu4] deltorphin. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993;266:820–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SULLIVAN A.F., DICKENSON A.H. Electrophysiological studies on the spinal antinociceptive action of kappa opioid agonists in the adult and 21-day-old rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;256:1119–11125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUZCS M., COSCIA C.J. Evidence for δ-opioid binding and GTP-regulatory proteins in 5-day-old rat brain membranes. J. Neurochem. 1990;54:1419–1425. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb01978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUZCS M., COSCIA C.J. Differential coupling of opioid binding sites to guanine triphosphate binding regulatory proteins in subcellular fractions of rat brain. J. Neutrosci. Res. 1992;31:565–572. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490310322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THORNTON S.R., COMPTON D.R., SMITH F.L. Ontogeny of mu opioid agonist anti-nociception in postnatal rats. Dev. Brain Res. 1998;105:269–276. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(97)00185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSENG L.F., COLLINS K.A., WANG Q. Differential ontogenesis of thermal and mechanical antinociception induced by morphine and β-endorphin. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;277:71–76. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00064-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WINDH R.T., KUHN C.M. Increased sensitivity to mu opiate antinociception in the neonatal rat despite weaker receptor-guanyl nucleotide protein coupling. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;273:1353–1360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XIA Y., HADDAD G.G. Ontogeny and distribution of opioid receptors in the rat brainstem. Brain Res. 1991;549:181–193. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90457-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAKI P.A., BILSKY E.J., VANDERAH T.W., LAI J., EVANS C.J., PORRECA F. Opioid receptor types and subtypes: the δ receptor as a model. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1996;36:379–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.002115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG X., BAO L., ARVIDDSSON U., ELDE R., HOKFELT T. Localization and regulation of the delta-opioid receptor in dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord of the rat and monkey: evidence for association with the membrane of large dense-core vesicles. Neurosci. 1998;82:1225–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]