Abstract

Activation of macrophages with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and low doses of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) induced apoptotic death through a nitric oxide-dependent pathway.

Treatment of cells with the immunosuppressors cyclosporin A (CsA) or FK506 inhibited the activation-dependent apoptosis.

These drugs decreased the up-regulation of p53 and Bax characteristic of activated macrophages. Moreover, incubation of activated macrophages with CsA and FK506 contributed to maintain higher levels of Bcl-2 than in LPS/IFN-γ treated cells.

The inhibition of apoptosis exerted by CsA and FK506 in macrophages was also observed when cell death was induced by treatment with chemical nitric oxide donors.

Incubation of macrophages with LPS/IFN-γ barely affected caspase-1 but promoted an important activation of caspase-3. Both CsA and FK506 inhibited pathways leading to caspase-3 activation. Moreover, the cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, a well established caspase substrate, was reduced by these immunosuppressive drugs.

CsA and FK506 reduced the release of cytochrome c to the cytosol and the activation of caspase-3 in cells treated with nitric oxide donors.

These results indicate that CsA and FK506 protect macrophages from nitric oxide-dependent apoptosis and suggest a contribution of the macrophage to innate immunity under conditions of immunosuppression of the host.

Keywords: Cyclosporin A, FK506, apoptosis, macrophages, lipopolysaccharide, interferon-γ, caspase-3, nitric oxide, cytochrome c

Introduction

Macrophages constitute a key component in the immune response releasing a large number of odd effector molecules involved in the initiation and mediation of sustained inflammatory reactions (MacMicking et al., 1997; Nathan & Hibbs, 1991; Nathan, 1997). Macrophages are mainly activated through T-lymphocyte dependent responses, but several bacterial components could contribute to the activation process through mechanisms of innate immunity (Nathan, 1997; Doherty, 1995; Carroll & Prodeus, 1998). Once activated, the macrophage initiates the transcription of genes coding for the expression of enzymes that participate in mounting the host response against pathogens (Doherty, 1995; Nathan & Xie 1994). Among them is the expression of iNOS, responsible for the large amount of NO production observed in activated macrophages (Nathan & Xie, 1994; Green & Nacy, 1993). This high-output NO synthesis triggers by itself apoptosis in these cells, and therefore macrophage activation is followed by apoptotic death (Albina et al., 1993; Terenzi et al., 1995). Several pathways leading to apoptosis in macrophages have been characterized, involving NO-dependent and independent mechanisms (Albina et al., 1993; Terenzi et al., 1995; Camels et al., 1997; Messmer et al., 1996b). Up-regulation of p53 by NO has been revealed as an early event in the apoptotic process, whereas overexpression of Bcl-2 prevented apoptotic death under different stimulatory conditions (Camels et al., 1997; Messmer & Brune, 1996; Messmer et al., 1996a).

Studies of inhibition of immune system activity in the course of immunosuppressive therapy have focused their attention on the effect of these drugs on T-lymphocyte activation (Sigal & Dumont, 1992; Shevach, 1985). In this regard, immunosuppression by CsA is due to its interaction with T lymphocytes, inhibiting the transcription of the IL-2 gene and the release of T-helper-dependent synthesis of lymphokines (Sigal & Dumont, 1992; Shevach, 1985; Schreiber & Crabtree, 1992). FK506 also acts as immunosuppressor, although through a different mechanism involving binding to a distinct cytoplasmic protein, generically recognized as immunophylins which share prolyl cis-trans isomerase activity (Mason, 1990; Quemeneur et al., 1998). However, both immunomodulators once bound to their cytosolic receptor mainly exert their effects through the interaction and inhibition of the protein phosphatase calcineurin (Dumont et al., 1992). Moreover, treatment of T-lymphocytes with CsA or FK506 has important effects on lymphocyte viability, depending on the way of activation; but in general, they potentiate apoptotic death (Horigome et al., 1997; Waring & Beaver, 1996). However, less attention has been paid to the establishment of macrophage function under immunosuppressive conditions, despite the fact that this cell might contribute to the innate immunity through the synthesis of reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates (Carroll & Prodeus, 1998; van Rooijen & Sanders, 1997). The ability of CsA and FK506 to inhibit macrophage-dependent NO synthesis has been described previously, and this mechanism involves both inhibition of transcription of the iNOS gene and the enzyme activity (Conde et al., 1995; Hattori & Nakanishi, 1995).

In view of the ability of immunosuppressors to induce apoptotic death in stimulated lymphocytes, and the potential contribution of macrophages to host defence, we investigated the effects of CsA and FK506 on macrophage viability. Our results show that low doses of CsA or FK506, in the range of those that exert a moderate inhibition of iNOS expression in LPS/IFN-γ activated peritoneal macrophages, prevent apoptosis through a mechanism compatible with an inhibition of caspase-3 activation and p53 over-expression as well as an alteration in the level of proteins of the Bcl-2 family, favouring the prevalence of the anti-apoptotic members of this group.

Methods

Chemicals

Chemical and biochemical reagents were from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), Boehringer (Mannheim, Germany) and Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) and were of the highest quality available. Caspase substrates and inhibitors were from Pharmingen (Hamburg, Germany). Materials and chemicals for electrophoresis were from Bio-Rad (Richmond, CA, U.S.A.) Antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.). Culture media were from Biowhittaker (Verviers, Belgium).

Treatment of mice and isolation of elicited peritoneal macrophages

Ten-week-old Balb/c mice were maintained free of pathogens and 4 days prior to use were i.p. injected 1 ml of sterile thioglycollate broth (0.1 g ml−1). Peritoneal macrophages were prepared as previously described (Velasco et al., 1997) and cells were seeded at 1×106 cm−2 in phenolred free RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% foetal calf serum. Non adherent cells were removed 2 h after seeding by extensive washing with medium.

Flow cytometric analysis

In vivo propidium iodide staining was carried out after incubation of the cells with the appropriate stimuli in the presence of 0.005% propidium iodide (Hortelano & Boscá, 1997). Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and then incubated with annexin V at room temperature following the recommendations of the supplier (Boehringer Mannheim). Cells were scraped off the dishes, maintained at 4°C and immediately analysed in a flow cytometer (Becton & Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, U.S.A.), equipped with a 5-W argon laser. The forward scatter was plotted against the propidium iodide fluorescence. Apoptotic cells shifted to the R2+R4 regions (Hortelano & Boscá, 1997; Genaro et al., 1995). To address the integrity of the DNA in each region, cells were sorted and analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis (see below). The DNA integrity of the cells stained with annexin V and present in the A2 and A1 panels was determined also after sorting.

Analysis of DNA degradation

Internucleosomal DNA fragmentation of sorted 106 cells (R1 and R2+R4 regions after staining with propidium iodide; A2 and A1 in cells stained with annexin V) was analysed in agarose gels as follows: the cell suspension was diluted in one vol of ice-cold buffer containing EDTA 20 mM, Triton X-100 1%, Tris-HCl 10 mM, pH 8.0 and incubated for 15 min at 4°C. Nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 500×g for 10 min and the resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 30,000×g for 15 min. The fragmented DNA present in the soluble fraction was precipitated with 70% ethanol plus MgSO4 2 mM, and aliquots were treated for 1 h at 55°C with 0.3 mg ml−1 of proteinase K. After two extractions with phenol : chloroform (vol : vol), the DNA was resuspended and analysed in a 2% agarose gel and stained with 0.5 μg ml−1 of ethidium bromide (Hortelano & Boscá, 1997; Genaro et al., 1995).

Caspase assay

The activity of caspase-1 and caspase-3 was determined in cell lysates using the YVAD-AMC and DEVD-AMC fluoregenic substrates and following the instructions of the supplier (Pharmingen). The corresponding peptide aldehydes were used to inhibit the caspase activity and to ensure the specificity of the reaction. The linearity of the caspase assay was determined over a 30 min reaction period.

Nitrite and nitrate determination

NO release to the culture medium was determined spectrophotometrically by the accumulation of nitrite and nitrate as described (Velasco et al., 1997). Nitrate was reduced to nitrite with nitrate reductase (Boehringer) and this was determined with Griess reagent by adding sulphanilic acid and naphthylenediamine (1 mM in the assay). The absorbance at 548 nm was compared with a standard of NaNO2.

Western blot analysis

Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, scraped off the dishes and recovered by centrifugation at 30,000×g for 30 s. Cystosolic extracts were prepared after homogenization with ice-cold (in mM) EDTA 1, DTT, 1, phenylmethyl sulphonylfluoride 0.5, 10 μg ml−1 of leupeptin and Tris-HCl 20 mM, pH 8.0, and centrifugation at 30,000×g for 10 min in a Eppendorf centrifuge. When cytochrome c was assayed, the homogenization buffer was supplemented with mannitol, 0.22 M, sucrose 68 mM and cytochalasin B 10 μM. Aliquots of 10 μg of the soluble protein were submitted to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10% gel) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Amersham). The level of the proteins p53, Bcl-2, Bax, Bcl-xl, PARP and cytochrome c was measured using specific antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) that recognized proteins of the expected size. The blots were revealed using the ECL technique (Amersham).

Statistical analysis

The data shown are the mean±s.e.mean of three or four experiments. Statistical significance was estimated with Student's t-test for unpaired observations. A P<0.05 was considered significant. In studies of Western blot analysis, linear correlations between increasing amounts of input protein and signal intensity were observed (correlation coefficients higher than 0.84).

Results

CsA and FK506 protect macrophages from LPS/IFN-γ-induced apoptosis

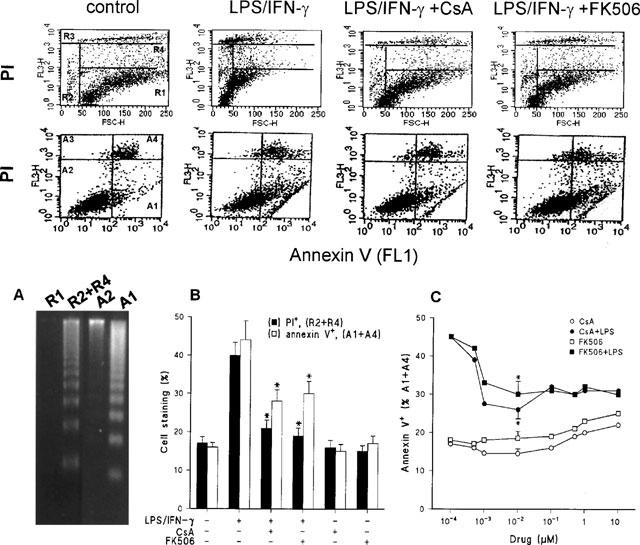

Incubation for 24 h of elicited peritoneal macrophages with low doses of LPS and IFN-γ induced apoptotic death as deduced by the shift in the staining with propidium iodide, corresponding to hypodiploid cells (R2+R4 regions), and by the binding of annexin V after exposure of phosphatidylserine residues to the extracellular medium (A1+A4 regions) when analysed by flow cell cytometry (Figure 1). The apoptotic nature of the cells present in the R2+R4 and A1 regions was confirmed after cell sorting and analysis of the DNA integrity in agarose gels (Figure 1A). The presence of CsA or FK506 in the incubation medium did not influence the viability of the cells as assessed by these criteria. However, these immunomodulators exerted an important protection against the opoptosis triggered by LPS/IFN-γ (Figure 1B). The dose dependent effect of CsA and FK506 on cell viability is shown in Figure 1C. Doses of CsA and FK506 in the range of 0.1–10 nM protected the macrophages from apoptosis, without cytotoxic effects as determined by the release of LDH to the culture medium (not shown). However, concentrations of these immunomodulators higher than 500 nM proved toxic for the cells as deduced by the marked increase in necrotic death (LDH release).

Figure 1.

CsA and FK506 decreased the amount of apoptotic macrophages and the binding of annexin V upon treatment with LPS/IFN-γ. Cultured peritoneal macrophages (106 cells) were stimulated for 24 h with combinations of 200 ng ml−1 of LPS and 10 u ml−1 of IFN-γ, CsA 10 nM or FK506 10 nM. The cells were analysed by flow cell cytometry after labelling with PI or staining with annexin V for the detection of the exposure of phosphatidylserine residues. LPS/IFN-γ activated macrophages corresponding to the R1, R2+R4, A2 and A1 panels were sorted (106 cells) and the DNA integrity was evaluated in agarose gels (A). The percentage of apoptotic cells (R2+R4 quadrants) after PI labelling (upper panels) or annexin V+ (A1+A4 quadrants of the lower panels) was quantified (B). The dose dependent effect of CsA or FK506 on the exposure of phosphatidylserine residues by control (open symbols) or activated macrophages (solid symbols) is shown in panel C. Results shown the mean±s.e.mean of three experiments. *P<0.01 with respect to the LPS/IFN-γ condition.

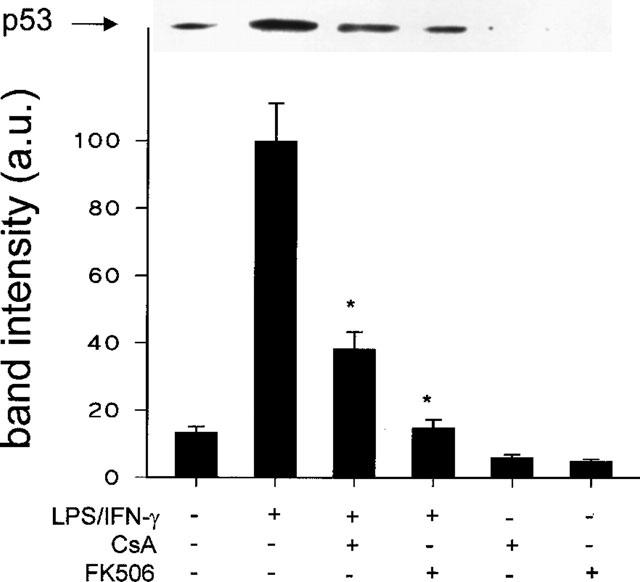

CsA and FK506 alter the Bcl-2/Bax ratio in activated macrophages

Further to characterize the mechanisms by which CsA and FK506 protect activated macrophages from apoptosis, the levels of potential proteins that participate in the control of apoptotic death were determined. In this regard, an important role for the regulation of apoptosis in activated macrophages has been attributed to p53 over-expression (Calmels et al., 1997; Messmer & Brune, 1996). To address this point, the amount of p53 was measured and as Figure 2 shows, cells treated with LPS/IFN-γ exhibited an important increase of p53. However, when activation was done in the presence of CsA or FK506, the levels of p53 measured after 24 h of treatment were barely detectable in these cells. It is worth mentioning that untreated macrophages exhibited moderate p53 levels after 24 h of culture, in agreement with the basal levels of apoptosis observed in these cells. Interestingly, lower levels of p53 were detected in cells incubated in the presence of CsA or FK506.

Figure 2.

p53 up-regulation is inhibited in activated macrophages incubated with CsA or FK506. Cells were incubated with combinations of LPS (200 ng ml−1), IFN-γ (10 u ml−1), CsA (10 nM), or FK506 (10 nM) for 24 h. Total cell extracts were prepared and equal amounts of protein were analysed by Western blot using an anti-p53 Ab. Results show the p53 band corresponding to a representative experiment and the mean±s.e.mean of the densitometries of the bands from four experiments. *P<0.01 with respect to the LPS/IFN-γ condition.

Cultured peritoneal macrophages constitutively express Bcl-2, and this protein has proved to be an important protector against apoptosis in macrophage cell lines (Messmer et al., 1996a, 1996b). For this reason, we investigated the distribution of proteins of the Bcl-2 family in this experimental model. As Figure 3A shows, Bcl-2 levels decreased more than 70% after LPS/IFN-γ challenge. Treatment of activated macrophages with FK506 resulted in sustained levels of Bcl-2, whereas this effect was less important in cells incubated with CsA. However, when cells were treated with either CsA or FK506, a 30% increase in the basal levels of Bcl-2 was observed (Figure 3A). Regarding Bax that heterodimerizes and counteracts the death repressor activity of Bcl-2 (Menguas et al., 1996), treatment with LPS/IFN-γ markedly increased the levels of this protein. The effect of LPS/IFN-γ was attenuated when either CsA (57% decrease) or FK506 (95% decrease) was also present. CsA and FK506 alone did not exhibit any effect on the basal levels of Bax. The ratio between the Bcl-2 and Bax levels is shown in Figure 3B and an important imbalance after 24 h of treatment with LPS/IFN-γ was observed. However, treatment with CsA or FK506 contributed to maintain higher Bcl-2/Bax ratios. In addition to Bcl-2, Bcl-xl also protects from apoptosis in macrophages (Okada et al., 1998) and the amount of this protein significantly decreased in LPS/IFN-γ treated cells. In the presence of CsA and to a lesser extent FK506, the levels of this protein in LPS/IFN-γ activated macrophages remained notably higher (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

CsA and FK506 attenuate the changes in the levels of proteins of the Bcl-2 family induced by treatment of macrophages with LPS/IFN-γ. Cells were treated as indicated in Figure 2 and soluble protein from the cell extracts was analysed by Western blot using anti-Bcl-2, anti-Bax and anti-Bcl-xl antibodies. Results show the densitometry of the bands (mean±s.e.mean) from four experiments (A). The ratio between the Bcl-2 and Bax levels corresponding to each condition is shown in B.

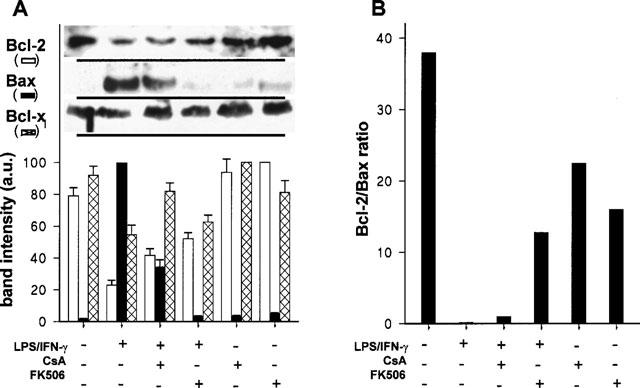

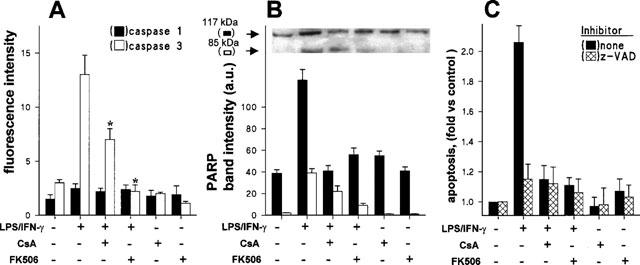

Caspase activation is attenuated by CsA and FK506 in cells treated with LPS/IFN-γ

Following the analysis of proteins involved in the early regulation of apoptotic death, the activity of caspases-1 and -3 that have been recognized as important executers of NO-dependent apoptosis, as well as the integrity of PARP as a marker of in vivo caspase activation were measured (Messmer et al., 1996b; Thornberry & Lazebnik, 1998). As Figure 4A shows, the activity of caspase-1 was slightly enhanced in LPS/IFN-γ stimulated cells, whereas an important increase of caspase-3 activity was observed under these conditions. Both CsA and FK506 decreased caspase-3 activation in LPS/IFN-γ treated cells (60% and complete inhibition, respectively). Regarding PARP as a target of caspase activation, the protein recognized in cultured peritoneal macrophages corresponded to the 117 kDa intact protein, with less than 6% cleaved 85 kDa PARP fragment (Figure 4B). Treatment of these cells with LPS/IFN-γ for 24 h was followed by a 4 fold increase in the total levels of PARP, as well as in the percentage (24%) of cleaved protein. The inhibition of PARP cleavage exerted by FK506 was more effective than that elicited by CsA (56 and 23% with respect to the levels of LPS/IFN-γ-treated cells).

Figure 4.

Effect of CsA and FK506 on LPS/IFN-γ-dependent caspase activation and PARP degradation. Macrophages were stimulated for 24 h with LPS/IFN-γ, CsA 10 nM, FK506 10 nM or combinations of these. Cell extracts were prepared and the activity of caspases-1 and -3 was measured using specific substrates and inhibitors (A). The extent of PARP cleavage, as an in vivo caspase substrate, was analysed by Western blot using a specific Ab (B). The effect of the caspase inhibitor z-VAD (20 μM) on apoptosis (propidium iodide staining) was evaluated in activated cells (C). Results (mean±s.e.mean, n=3) show the caspase activity (*P<0.01 vs the LPS/IFN-γ condition), the band intensities of PARP fragments, and the apoptosis upon normalization with respect to unstimulated cells.

To establish the relevance of caspase activation in the induction of apoptosis, experiments were undertaken in which the effect of the caspase inhibitor z-VAD was analysed. As Figure 4C shows, this inhibitor reduced more than 80% the apoptosis triggered by LPS/IFN-γ activation. Interestingly, z-VAD did not affect significantly the apoptosis observed in activated cells treated with CsA or FK506, which suggests that they act on a common pathway controlled by the presence of these immunomodulators in the incubation medium.

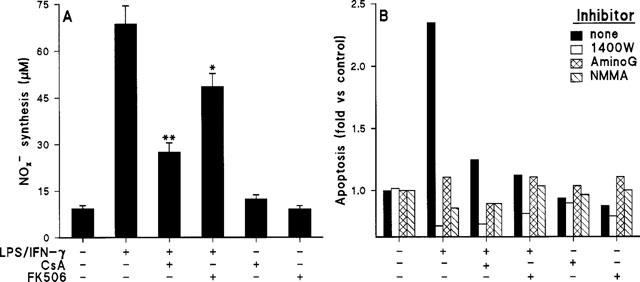

CsA and FK506 protect macrophages from the NO-dependent apoptosis

Activation of macrophages with LPS/IFN-γ induces the expression of the high-output iNOS, and therefore, the synthesis of large amounts of NO. This process can be partially inhibited by the treatment of the cells with CsA or FK506 (Conde et al., 1995; Hattori & Nakanishi, 1995), and this decrease in NO synthesis might be involved in the mechanism of protection exerted by CsA and FK506. As Figure 5A shows, the accumulation of NOx− in the culture medium of LPS/IFN-γ activated macrophages is inhibited 69 and 34% in the presence of CsA and FK506, respectively. Since the activation of macrophages with LPS/IFN-γ involves the engagement of several signalling pathways that may regulate apoptosis independently of the synthesis of NO, we decided to determine the extent of apoptosis in the absence of NO synthesis. To do this, macrophages were cultured in the presence of the NOS inhibitors NMMA, AminoG and 1400W, and the effect of these on apoptosis was measured. As Figure 5B shows, when NO synthesis was inhibited apoptosis was completely blocked. These results suggest that induction of apoptosis in cultured macrophages activated by suboptimal doses of LPS/IFN-γ is mainly mediated through the synthesis of NO.

Figure 5.

Effect of CsA and FK506 on NO synthesis in activated macrophages. Protection from apoptosis in the absence of NO synthesis. Cells were treated as indicated in Figure 2 and the amount of nitrite plus nitrate released was measured (A). NOS activity was inhibited with 200 μM of 1400W, aminoguanidine (AminoG) or NMMA. Apoptosis was determined by staining the cells with propidium iodide and measuring the percentage of cells in the R2+R4 regions. Apoptosis (mean of two experiments) was expressed upon normalization with respect to control unstimulated cells (B). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 with respect to the LPS/IFN-γ condition.

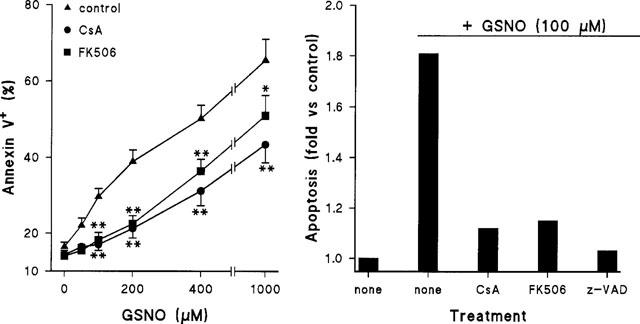

To analyse more closely the contribution of the NO-dependent pathway to apoptosis in macrophages and its negative regulation by CsA and FK506, NO synthesis was accomplished via treatment of the cells with chemical NO-donors. As Figure 6A shows, GSNO induced a rapid apoptotic death as reflected by the increase of annexin V binding to the plasma membrane (6 h of incubation). Indeed, treatment of the cells with CsA or FK506 protected them efficiently from the apoptosis induced by doses of GSNO below 200 μM. The same experiment was performed in cells treated with 100 μM GSNO, using a caspase inhibitor and, as Figure 6B shows, z-VAD was effective protecting against NO-dependent apoptotic death.

Figure 6.

CsA and FK506 inhibit the apoptosis induced by low doses of GSNO. Macrophages were treated for 6 h with the indicated doses of a fresh solution of GSNO and 10 nM of CsA or FK506. The percentage of annexin V+ cells was determined by flow cytometry (A). The protection exerted by z-VAD (20 μM) in cells treated with 100 μM GSNO was also measured (B). Results show the mean±s.e.mean (n=4) (A) or the mean of two experiments (B). *P<0.05, **P<0.005 with respect to the condition in the absence of immunomodulator.

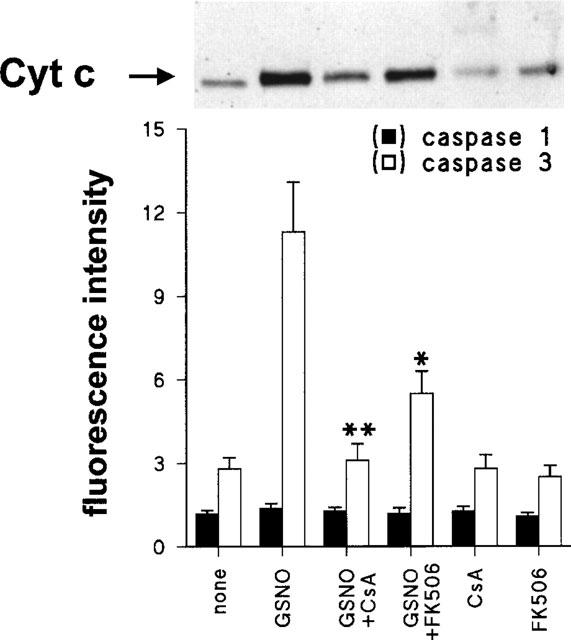

To better establish the mechanism of protection by immunosuppressors, the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria to the cytosol and the activation of caspases-1 and -3 were determined. As Figure 7 shows, treatment of macrophages with 200 μM GSNO promoted an important release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria to the cytosol, as well as an activation of caspase-3, but not of caspase-1. However, both the release of cytochrome c and the activation of caspase-3 were significantly attenuated in the presence of CsA and FK506 (4 and 49% of the caspase-3 activation in the presence of GSNO, respectively).

Figure 7.

Cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation in macrophages treated with GSNO. Cells were incubated for 4 h with GSNO 200 μM, CsA 10 nM, FK506 10 nM or combinations of these. Cells were homogenized in conditions to preserve mitochondrial integrity and the cytosolic extracts were analysed to determine the amount of cytochrome c by Western blotting (17 kDa band), and the activity of caspase-1 and -3, respectively. Results show that the mean±s.e.mean of three experiments. *P<0.01, **P<0.001 with respect to cells treated with GSNO.

Discussion

The behaviour of the macrophage under immunosuppressive therapy constitutes a subject of interest since under these conditions, the contribution of innate immunity to host defence represents a main component of the immune response (Doherty, 1995; Carroll & Prodeus, 1998).

Activation of macrophages with low doses of LPS and IFN-γ results in a notable induction of apoptosis when analysed by annexin V binding, PI staining, or the appearance of DNA laddering in agarose gels (Albina et al., 1993; Messmer et al., 1996a, 1996b; this work). The kinetics of each process is slightly different annexin V staining being the first quantitative manifestation of apoptotic death (Hobrug et al., 1995). Recently, the characterization of the pathways controlling apoptosis in macrophages provided valuable information about the different steps involved (Albina et al., 1993; Terenzi et al., 1995; Calmels et al., 1997; van Rooijen & Sanders, 1997). Accordingly, we investigated the contribution of several proteins involved in the control of cell viability under immunosuppressive conditions. Our data show that macrophage activation-dependent apoptosis is inhibited efficiently by CsA and FK506 assayed at 10 nM concentrations. Indeed, it is to note that CsA and FK506 not only inhibited apoptosis in activated cells but also prevented the characteristic endogenous basal apoptosis observed in cultured macrophages, suggesting that these drugs exhibit a negligible toxicity in these cells. These data contrast with the effects of CsA and FK506 on cell viability studied in other cell types. For example, in human peripheral blood cells the presence of CsA increases apoptosis once activated in vitro with concanavalin A (Horigome et al., 1997). However, in thymocytes, CsA prevents apoptosis induced by low doses of thapsigargin (2–10 nM) (Waring & Beaver, 1996).

To summarize the results obtained, apoptosis in peritoneal macrophages after LPS/IFN-γ activation conditions is mainly dependent on NO synthesis; and in fact, when iNOS activity was inhibited the percentage of apoptotic cells diminished dramatically. The doses of CsA or FK506 used in this work exerted only a moderate inhibition of NO synthesis (Wang et al., 1997; Liebermann et al., 1995), indicating that these drugs inhibit specific apoptotic pathways. With respect to the mechanisms involved in the protection exerted by these immunosuppressors, we observed a significant unresponsiveness to p53 up-regulation in macrophages treated with CsA and FK506, and it has been well established that this pathway is one of the upstream inducers of apoptosis in cells challenged with NO-donors (Calmels et al., 1997; Messmer & Brune, 1996; Agarwal et al., 1998). Interestingly, several pro-apoptotic proteins, among them Bax, have been reported as transcriptional targets of p53 (Mitry et al., 1997), and in agreement with these observations, low levels of Bax have been detected in cells treated with immunosuppressors. Regarding Bcl-2, overexpression of this anti-apoptotic protein counteracted p53-dependent apoptosis in RAW 264.7 cells (Messmer et al., 1996a). From these data, sustained Bcl-2 levels should be expected in activated cells treated with CsA or FK506. However, this was not the case in our study, and a significant fall in Bcl-2 levels was observed in the presence of CsA, although attenuated with respect to those elicited by LPS/IFN-γ. Since proteins of the Bcl-2 family act as dimers, this apparent paradox can be explained if one considers the relative abundance of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins (Messmer et al., 1996a; Hortelano & Boscá, 1997; Kroemer, 1997); and in fact, higher Bcl-2/Bax ratios were observed in cells treated with immunosuppressors. In addition to this, it is important to note the high levels of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-xl measured in these cells. The apoptogenic protein Bcl-xs was also analysed, but its levels were virtually undetectable under our experimental conditions. The relevance of Bcl-xl in macrophage function is reinforced by the observation that in RAW 264.7 the basal levels are low and activation with LPS/IFN-γ up-regulates Bcl-xl (Lotem & Sachs, 1995; Okada et al., 1998). This increase in Bcl-xl transiently protects against apoptogenic stimuli. Moreover, evidence has been obtained indicating that Bcl-xl is important to maintain mitochondrial membrane potential and volume homeostasis, and therefore, the high levels observed in cultured macrophage might contribute to the maintenance of viability (Vander Heiden et al., 1997).

Previous studies have identified the mitochondrial permeability transition as a target of the apoptotic action of NO both in intact cells and in reconstituted systems containing mitochondrial and nuclei enriched preparations (Hortelano et al., 1997; Green & Reed, 1998; Green & Kroemer, 1998), and this point might constitute a common pathway in the activation of apoptosis via caspases and proteins of the Bcl-2 family (Marzo et al., 1998). Indeed, caspase-3 was activated both in LPS/IFN-γ and GSNO treated cells and this process was inhibited by CsA and FK506. In agreement with these data the cleavage of PARP that was measured as a target of caspase activation, was inhibited significantly in the presence of immunosuppressors. Taken on the whole, our results indicate that both immunosuppressors interact with several pro-apoptotic, and in part overlapping pathways in peritoneal macrophages, and suggest that viability of activated cells is improved in the course of immunosuppressive therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Alberto Alvarez from the Centro de Citometría de flujo for help in the FACS analysis, O.G. Bodelón for technical help and E. Lundin for the critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grant PM95-007 form Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain.

Abbreviations

- CsA

cyclosporin A

- DEVD-AMC

N-acetyl-DEVD-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin

- GSNO

S-nitrosoglutathione

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NMMA

N-monomethylarginine

- PARP

poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase

- PI

propidium iodide

- YVAD-AMC

N-acetyl-YVAD-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin

- z-VAD

z-Val-Ala-DL-Asp-fluoromethylketone

- 1400W

N-(3-(aminomethyl)benzyl)acetamidine

References

- AGARWAL M.L., TAYLOR W.R., CHERNOV M.V., CHERNOVA O.B., STARK G.R. The p53 network. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:1–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALBINA J.E., CUI S., MATEO R.B., REICHNER J.S. Nitric oxide-mediated apoptosis in murine peritoneal macrophages. J. Immunol. 1993;150:5080–5085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CALMELS S., HAINAUT P., OHSHIMA H. Nitric oxide induces conformational and functional modifications of wild-type p53 tumor suppressor protein. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3365–3369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARROLL M.C., PRODEUS A.P. Linkages of innate and adaptive immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1998;10:36–40. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONDE M., ANDRADE J., BEDOYA F.J., SANTA MARIA C., SOBRINO F. Inhibitory effect of cyclosporin A and FK506 on nitric oxide production by cultured macrophages. Evidence of a direct effect of nitric oxide synthase activity. Immunology. 1995;84:476–481. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOHERTY T.M. T-cell regulation of macrophage function. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1995;7:400–404. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUMONT F.J., STARUCH M.J., KOPRAK S.L., SIEKIERKA J.J., LIN C.S., HARRISON R., SEWELL T., KINDT V.M., BEATTIE T.R., WYVRATT M.The immunosuppressive and toxic effects of FK-506 are mechanistically related: pharmacology of a novel antagonist of FK-506 and rapamycin J. Exp. Med. 1992176751–760.et al [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GENARO A.M., HORTELANO S., ALVAREZ A., MARTÍNEZ A.C., BOSCÁ L. Splenic B lymphocyte programmed cell death is prevented by nitric oxide release through mechanisms involving sustained Bcl-2 levels. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;95:1884–1890. doi: 10.1172/JCI117869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREEN D., KROEMER G. The central executioners of apoptosis: caspases or mitochondria. Trends. Cell Biol. 1998;8:267–271. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREEN D.R., REED J.C. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science. 1998;281:1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREEN S.J., NACY C.A. Antimicrobial and immunopathological effects of cytokine-induced nitric oxide synthesis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 1993;6:384. [Google Scholar]

- HATTORI Y., NAKANISHI N. Effects of cyclosporin A and FK506 on nitric oxide and tetrahydrobiopterin sysnthesis in bacterial lipopolysaccharide-treated J774 macrophages. Cell Immunol. 1995;165:7–11. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOBRUG C.H.E., DE HASS M., VOM DEM BORNE A.E.G., VERHOVEN A.J., REUTLINGSPERGER C.P.M., ROOS D. Human neutrophils lose their surface FCγRIII and acquire annexin V binding sites during apoptosis in vitro. Blood. 1995;85:532–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORIGOME A., HIRANO T., OKA K., TAKEUCHI H., SAKURAI E., KOZAKI K., MATSUNO N., NAGAO T., KOZAKI M. Glucocorticoids and cyclosporine induce apoptosis in mitogen-activated human peripheral mononuclear cells. Immunopharmacology. 1997;37:87–94. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(97)00036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORTELANO S., BOSCÁ L. 6-Mercaptopurine decreases the Bcl-2/Bax ratio and induces apoptosis in activated splenic B lymphocytes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;51:414–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORTELANO S., DALLAPORTA B., ZAMZAMI N., HIRSCH T., SUSIN S.A., MARZO I., BOSCÁ L., KROEMER G. Nitric oxide induces apoptosis via triggering mitochondrial permeability transition. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:373–377. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00623-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KROEMER K. The proto-oncogene Bcl-2 and its role in regulating apoptosis. Nat. Med. 1997;3:614–620. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIEBERMANN D.A., HOFFMAN B., STEINMAN R.A. Molecular controls of growth arrest and apoptosis: p53-dependent and independent pathways. Oncogene. 1995;11:199–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOTEM J., SACHS L. Regulation of bcl-2, bcl-xL and bax in the control of apoptosis by hematopoietic cytokines and dexamethasone. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6:647–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACMICKING J., XIE Q.W., NATHAN C. Nitric oxide and macrophage function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997;15:323–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARZO I., BRENNER C., ZAMZAMI N., SUSIN S.A., BEUTNRE G., BRDICZKA D., REMY R., XIE Z.H., REED J.C., KROEMER G. The permeability transition pore complex: A target for apoptosis regulation by caspases and Bcl-2-related proteins. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:1261–1271. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASON J. Pharmacology of cyclosporine (sandimmune). VII. Pathophysiology and toxicology of cyclosporine in humans and animals. Pharmacol. Rev. 1990;41:423–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MENGUAS K., RIORDAN F.A., HOFFBRAND A.V., WICKREMASINGHE R.G. Co-ordinate downregulation of bcl-2 and bax expression during granulocyte and macrophage-like differentiation of the HL60 promyelocytic leukaemia cell line. FEBS Lett. 1996;394:356–360. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MESSMER U.K., BRUNNE B. Nitric oxide-induced apoptosis: p53-dependent and p53-independent signalling pathways. Biochem. J. 1996;319:299–305. doi: 10.1042/bj3190299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MESSMER U.K., REED U.K., BRUNE B. Bcl-2 protects macrophages from nitric oxide-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1996a;271:20192–20197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MESSMER U.K., REINER D.M., REED J.C., BRUNE B. Nitric oxide induced poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase apoptosis is blocked by Bcl-2. FEBS Lett. 1996b;384:162–166. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITRY R.R., SARRAF C.E., WU C.G., PIGNATELLI M., HABIB N.A. Wild-type p53 induces apoptosis in Hep3B through up-regulation of bax expression. Lab. Invest. 1997;77:369–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NATHAN C. Inducible nitric oxide synthase: what difference does it make. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:2417–2423. doi: 10.1172/JCI119782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NATHAN C., HIBBS J.B., Jr Role of nitric oxide synthesis in macrophage antimicrobial activity. Curr. Op. Immunol. 1991;3:65–70. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(91)90079-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NATHAN C., XIE Q.-W. Nitric oxice synthases: roles, tolls and controls. Cell. 1994;78:915–918. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKADA S., ZHANG H., HATANO M., TOKUHISA T. A physiological role of Bcl-xL induced in activated macrophages. J. Immunol. 1998;160:2590–2596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUEMENEUR E., MOUTIEZ M., CHARBONNIER J.B., MENEZ A. Engineering cyclophilin into a proline-specific endopeptidase. Nature. 1998;391:301–304. doi: 10.1038/34687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHREIBER S.L., CRABTREE G.R. The mechanism of cyclosporin A and FK-506. Immunol. Today. 1992;13:136–142. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90111-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEVACH E.M. The effects of cyclosporin A on the immune system. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1985;3:397–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.03.040185.002145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIGNAL N.H., DUMONT F.J. Cyclosporin A, FK-506, and rapamycin: pharmacologic probes of lymphocyte signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1992;10:519–560. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.002511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TERENZI F., DÍAZ-GUERRA M.J.M., CASADO M., HORTELANO S., LEONI S., BOSCÁ L. Bacterial lipopeptides induce nitric oxide synthase and promote apoptosis through nitric oxide-independent pathways in rat macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:6017–6021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THORNBERRY N.A., LAZEBNIK Y. Caspases: Enemies within. Science. 1998;281:1312–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANDER HEIDEN M., CHANDEL N.S., WILLIAMSON E.K., SCHUMACKER P.T., THOMPSON C.B. Bcl-xl regulates the membrane potential and volume homeostasis of mitoch. Cell. 1997;91:627–637. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN ROOIJEN N., SANDERS A. Elimination, blocking, and activation of macrophages: three of a kind. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1997;62:702–709. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.6.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VELASCO M., DÍAZ-GUERRA M.J.M., DÍAZ-ACHIRICA P., ANDREU D., RIVAS L., BOSCÁ L. Macrophage triggering with cecropin A and melittin-derived peptides induces type II nitric oxide synthase expression. J. Immunol. 1997;197:4437–4443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG M.S., ZELENY-POOLEY M., GOLD B.G. Comparative dose-dependence study of FK506 and cyclosporin A on the rate of axonal regeneration in the rat sciatic nerve. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;283:1084–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WARING P., BEAVER J. Cyclosporin A rescues thymocytes from apoptosis induced by very low concentrations of thapsigargin: effects on mitochondrial function. Exp. Cell Res. 1996;227:264–276. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]