Abstract

The receptors which mediate the effects of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), amylin and adrenomedullin on the guinea-pig vas deferens have been investigated.

All three peptides cause concentration dependant inhibitions of the electrically stimulated twitch response (pD2s for CGRP, amylin and adrenomedullin of 7.90±0.11, 7.70±0.19 and 7.25±0.10 respectively).

CGRP8–37 (1 μM) and AC187 (10 μM) showed little antagonist activity against adrenomedullin.

Adrenomedullin22–52 by itself inhibited the electrically stimulated contractions of the vas deferens and also antagonized the responses to CGRP, amylin and adrenomedullin.

[125I]-adrenomedullin labelled a single population of binding sites in vas deferens membranes with a pIC50 of 8.91 and a capacity of 643 fmol mg−1. Its selectivity profile was adrenomedullin> AC187>CGRP=amylin. It was clearly distinct from a site labelled by [125I]-CGRP (pIC50=8.73, capacity=114 fmol mg−1, selectivity CGRP>amylin=AC187>adrenomedullin). [125I]-amylin bound to two sites with a total capacity of 882 fmol mg−1.

Although CGRP has been shown to act at a CGRP2 receptor on the vas deferens with low sensitivity to CGRP8–37, this antagonist displaced [125I]-CGRP with high affinity from vas deferens membranes. This affinity was unaltered by increasing the temperature from 4°C to 25°C, suggesting the anomalous behaviour of CGRP8–37 is not due to temperature differences between binding and functional assays.

Keywords: CGRP; amylin; adrenomedullin; CGRP2 receptor; vas deferens, guinea-pig; adrenomedullin22–52; CGRP8–37

Introduction

Adrenomedullin is a peptide which was recently isolated from human phaeochromocytomas (Kitamura et al., 1993a). Human and rat adrenomedullin are respectively 52 and 50 amino acids long. It is possible to remove the first 12 amino acids with little change in potency (Lin et al., 1994). The resulting peptide shows some similarity to members of the calcitonin family of peptides, especially CGRP and amylin. Although homology at the level of the primary sequence is weak between adrenomedullin and either CGRP or amylin, there are stronger relationships between the secondary structures of the peptides. They all have a six residue ring structure close to their N-termini, formed by an intramolecular disulphide bond. This is then followed by a region of potential amphipathic α-helix, and they all have a C-terminal amide (Kitamura et al., 1993b).

In view of the similarity between CGRP, adrenomedullin and amylin, it might be expected that there would be cross-reactivity between these peptides at their cognate receptors. The pharmacology of these peptides is complicated, but recent data suggests that the CGRP and adrenomedullin receptors may be the product of the same gene, called calcitonin receptor like receptor (CRLR) (Aiyar et al., 1996). Specificity is determined by accessory proteins belonging to the RAMP family (receptor activity modifying proteins), with RAMP1 co-expression leading to a CGRP receptor, and RAMP2 co-expression resulting in an adrenomedullin receptor (McLachtie et al., 1998). There is also evidence for subtypes of CGRP receptors (Quirion et al., 1992, Poyner, 1995; 1997b for reviews). To a first approximation CGRP receptors can be divided into two subclasses; CGRP1 which have a high affinity for the antagonist CGRP8–37 and CGRP2, which are much less sensitive to this compound. CRLR gives a CGRP1-like receptor. Both amylin and adrenomedullin can activate CGRP1 receptors, although they are less potent than CGRP itself. Little is known about the potencies of these peptides at CGRP2 receptors and relatively little characterization of any kind has been done on CGRP2 receptors. One major puzzle with this subclass of receptors is that CGRP8–37 shows a high affinity in radioligand binding studies, in contrast to its behaviour in functional studies (Dennis et al., 1990; Quirion et al., 1992). There is no explanation for this discrepancy, although it has been noted that the binding and functional assays are carried out under very different conditions (Poyner, 1995).

Amylin can bind to a site that has a very distinctive pharmacology, having a high affinity for calcitonin and somewhat lower affinity for CGRP (Veale et al., 1994). This site was first discovered in the CNS and is often termed the C3 binding site (Sexton et al., 1988). It is likely to represent a receptor through which amylin mediates many of its unique biological effects (Beaumont et al., 1995). There is evidence to suggest that this receptor may be a version of the C1a calcitonin receptor which has been subject to post-translational modification, or association with another protein such as RAMP1 (Chen et al., 1997; Sexton et al., 1999). Amylin also has a second class of binding site which is found in peripheral tissues; however this has a higher affinity for adrenomedullin and probably represents an adrenomedullin receptor (Aiyar et al., 1995; Owji et al., 1995). Radio-iodinated adrenomedullin binds to sites which have extremely high specificity for adrenomedullin over CGRP and amylin. It is possible that these correspond to the sites which are labelled with amylin and their apparent extreme specificity is an artefact due to the iodination of adrenomedullin (Owji et al., 1995), although functional studies of adrenomedullin receptors in Rat2 and Swiss 3T3 cells do confirm that these receptors are only very poorly activated by CGRP (Withers et al., 1996; D.M.S. & H.A. Coppock, unpublished observations).

Adrenomedullin is a very potent vasodilator, a property which it shares with CGRP. However, it is widely distributed, apparently functioning as a local hormone in many tissues, and it is apparent that its actions extend beyond the cardiovascular system. We have previously reported the existence of distinct receptors that mediate the effects of CGRP and amylin on the guinea-pig vas deferens (Tomlinson & Poyner, 1996). In this report we extend these studies to show the existence of a separate adrenomedullin receptor on this tissue. We also have further characterized the CGRP2 receptor subtype which is found here.

Some of these results have been previously published in abstract form (Poyner, 1997a).

Methods

Materials

Rat adrenomedullin was obtained from Peptide Institute Inc. (Osaka, Japan) and human αCGRP was obtained from Calbiochem (Nottingham, U.K.). Rat αCGRP and amylin were custom synthesized by ASG University (Szedgel, Hungary). It should be noted that rat and human CGRP show essentially identical properties in binding to and activating CGRP receptors (see Poyner, 1992 for review). All peptides were checked for correct molecular weight by mass spectroscopy. Peptide solutions were made up as 1 mM or 100 μM stock solutions in distilled water based on their nominal molecular weight, and subsequently diluted in buffer containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin. [125I]-iodohistidyl human αCGRP (specific activity 74TBq mmol−1) and Na [125I] were supplied by Amersham International (Little Chalfont, Bucks, U.K.). [125I]-Bolton Hunter reagent was supplied by NEN Life Science Products (Hounslow, Middlesex, U.K.). Iodogen reagent was supplied by Pierce (Rockford, Illinois, U.S.A.). Other reagents were obtained as described previously (Tomlinson & Poyner, 1996).

Peptide iodination

Rat adrenomedullin was iodinated by the iodogen (1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-3α,6α-diphenylglycoluril) method as previously described (Owji et al., 1995). Briefly, 12.5 μg (2 nmoles) of peptide in 10 μl of 0.2 M phosphate buffer pH 7.2 were reacted with 37 MBq of Na [125I] and 10 μg of iodogen reagent for 4 min at 22°C. The [125I]-peptide was purified by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (Waters C18 Novapak, Millipore, Milford MA, U.S.A.) using a 15–40% acetonitrile/water/0.05% trifluoroacetic acid gradient. Fractions showing binding were aliquoted, freeze-dried and stored at −80°C. The specific activity was 10 Bq fmol−1, as determined by radio-immunoassay.

Rat amylin was iodinated by the Bolton-Hunter method as previously reported (Bhogal et al., 1992) except that the reaction was performed at pH 9 for 1 h at room temperature. Its specific activity was 33 Bq fmol−1, determined by comparison of saturation and competitive binding assays.

Membrane preparation

Membranes were prepared by differential centrifugation as previously described (Bhogal et al., 1993). Briefly, whole vas deferens from Dunkin-Hartley guinea-pigs (350 g, Harlan U.K. Ltd, Bicester, Oxon, U.K.) were homogenized in ice-cold 50 mM HEPES pH 7.6 containing 0.25 M sucrose, 10 μg ml−1 pepstatin, 0.25 μg ml−1 leupeptin and antipain, 0.1 mg ml−1 benzamidine and bacitracin and 30 μg ml−1 aprotinin. The homogenates were centrifuged at 1500×g for 20 min at 4°C and the supernatants centrifuged at 100,000×g for 1 h at 4°C. The pellets were resuspended in 10 volumes of the above buffer without sucrose and centrifuged at 100,000×g for 1 h at 4°C.

Adrenomedullin binding assays

Membranes (100 μg protein) were incubated for 30 min at 4°C in 0.5 ml of binding buffer of composition (mM); HEPES, 20 (pH 7.4); MgCl2, 5; NaCl, 10; KCl, 4; EDTA, 1; phosphoramidon, 0.001 and 0.3% bovine serum albumin containing 500 Bq (100 pM) [125I]-adrenomedullin (Owji et al., 1995). Bound and free label was separated by centrifugation at 15,000×g for 2 min at 4°C. Non specific binding was determined in the presence of 1 μM unlabelled rat adrenomedullin. The integrity of the labels after binding was determined by fast protein liquid chromatography using reversed-phase C2/C18 columns (pepRPC HR5/5, Pharmacia Biotech, St Albans, Herts, U.K.) as previously described (Bhogal et al., 1992) and more than 95% co-eluted with the standard (results not shown).

Amylin binding assays

Vas deferens membranes (100 μg) were incubated for 60 min at 4°C with 500 Bq (30 pM) [125I]-rat amylin in binding buffer as for the adrenomedullin binding assays. Bound and free label were separated by centrifugation as described above and non-specific binding was determined in the presence of 200 nM rat amylin.

CGRP binding assays

Vas deferens membranes (100 μg) were resuspended in 0.5 ml of buffer of the following composition (mM): sodium chloride, 100; bacitracin, 0.4; HEPES 20 (pH 7.5) and 0.3% bovine serum albumin. Binding assays were carried out in the presence of 100 pM [125I]-iodohistidyl-human αCGRP for either 30 min (at 25°C) or 2 h (at 4°C). Assays were terminated by microcentrifugation, as described above. Non-specific binding was determined in the presence of 1 μM CGRP.

Protein measurements

Protein was measured by the Biuret assay.

Contractile responses of the isolated vas deferens

Vas deferens were removed from Dunkin-Hartley guinea-pigs and dose-response curves to peptides were obtained as described previously (Tomlinson & Poyner, 1996).

Analysis of data

Binding data from the [125I]-adrenomedullin or amylin displacement experiments was analysed by non-linear regression using the ‘Receptor-Fit' programme (Lundon Software, Cleveland, OH, U.S.A.) to calculate the dissociation constant (KD), the IC50 and the concentration of binding sites (Bmax). Analysis of one site versus two site competition curves was by F-test, with two component fits considered significant at P<0.05. The analysis of the [125I]-CGRP displacement curves and concentration response curves was done with EBDA/LIGAND to estimate IC50/EC50 values and Hill coefficients (nH). Analysis of Hill coefficients was by Students unpaired t-test, with a site being considered heterogeneous if the coefficient was significantly different (P<0.05) from unity.

The IC50/EC50 values from individual experiments (expressed in terms of molarity) were converted to pIC50s by taking their negative logarithim. They are expressed as means±s.e.means throughout the text.

For the contractile studies, each dose response curves was fitted to a logistic equation by means of the EBDA/Ligand routine to obtain an EC50 for the agonist. These were converted to pD2 values by taking negative logarithims. Responses were expressed as percentages of the resting tension before addition of agonist (but after addition of antagonist). The effects of antagonists were examined by comparing responses before and after antagonist treatment by means of Student's unpaired t-test or a one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test depending on whether single or multiple comparisons were being made. Significance was accepted at the P<0.05 level.

Results

Contractile responses of the isolated vas deferens

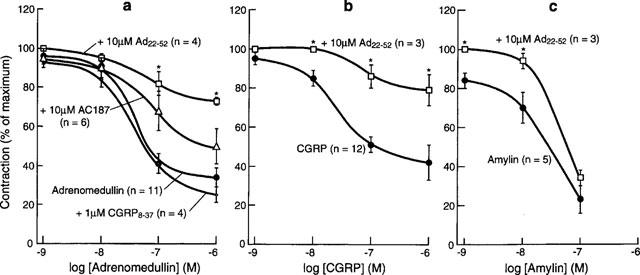

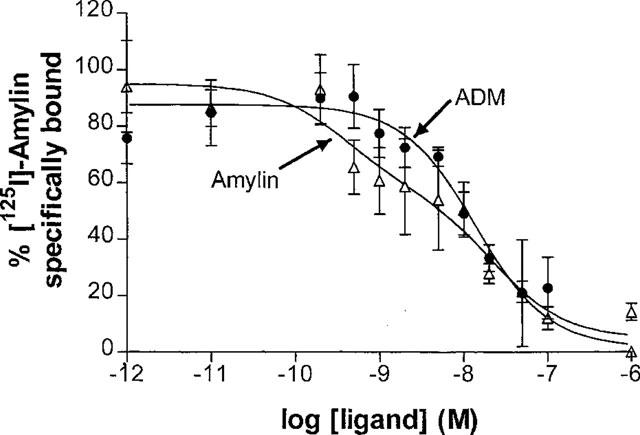

In confirmation of previous results (Tomlinson & Poyner, 1996), both human αCGRP and rat amylin produced dose-dependent inhibitions of the contractions of the electrically stimulated guinea-pig vas deferens (pD2s of 7.90±0.11 and 7.70±0.19 respectively; Figure 1). Adrenomedullin also caused a potent inhibition of electrically stimulated contractions, producing an effect very similar to that of amylin (pD2 of 7.25±0.10; Figure 1a). Previously it was shown that the responses to both CGRP and amylin were insensitive to CGRP8–37, but the response to CGRP was inhibited by AC187. The response to adrenomedullin was completely unaltered by the presence of 1 μM CGRP8–37. In the presence of 10 μM AC187 there was a small rightwards shift (pD2 of 6.55±0.24), which however failed to achieve significance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relaxation of the electrically stimulated vas deferens by (a) adrenomedullin, (b) CGRP and (c) amylin in the presence of potential antagonists. Values are means±s.e.means, n values shown in brackets. *Significantly different from response to agonist alone, P<0.05.

There have been reports that adrenomedullin22–52 can block some effects of adrenomedullin. When added to this preparation it was obvious that the chief response of adrenomedullin22–52 was itself to reduce the magnitude of the electrically stimulated contraction (Figure 2). Neither CGRP8–37 nor AC187 altered resting tension. In addition to this effect it also significantly inhibited the response to adrenomedullin, but this was also seen against CGRP and amylin (Figure 1a,b,c), although the inhibition of the amylin response was much less marked than that seen against the other two peptides.

Figure 2.

Relaxation of the electrically stimulated vas deferens by adrenomedullin22–52, Values are means±s.e.means of three determinations.

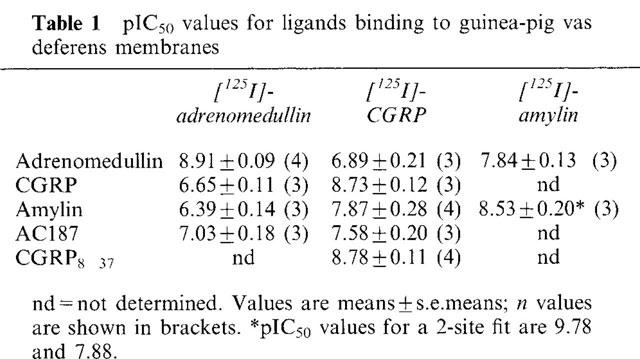

Radioligand binding studies with [125I]-adrenomedullin

[125I]-adrenomedullin bound with high affinity to a single class of binding sites on membranes made from guinea-pig vas deferens (Table 1, Figure 3a), with a capacity of 646±34 fmol receptor mg−1 protein. CGRP and amylin were both well over a hundred times less potent at displacing the radiolabel than adrenomedullin itself. AC187 was the most potent inhibitor of [125I]-adrenomedullin binding, but even this was 75 fold less potent than adrenomedullin (Table 1, Figure 3b).

Table 1.

pIC50 values for ligands binding to guinea-pig vas deferens membranes

Figure 3.

Displacement of [125I]-adrenomedullin by (a) adrenomedullin and (b) AC187, CGRP and amylin in vas deferens membranes. Values are means±s.e.means of three determinations.

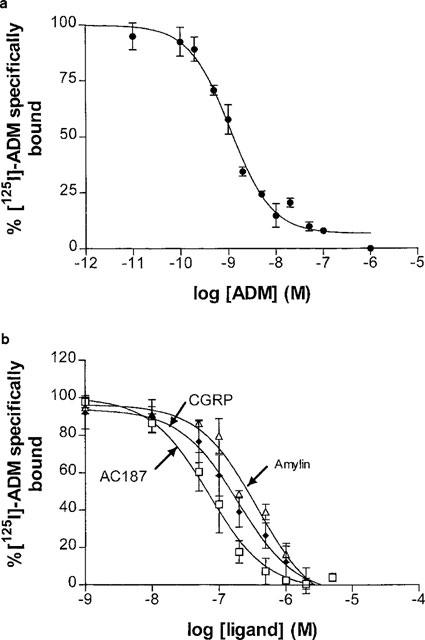

Radioligand binding studies with [125I]-amylin

[125I]-amylin bound to sites with a total capacity of 882±172 fmol receptor mg−1 protein (Figure 4). The binding curve was best fitted to a two-site model, where the high affinity site had an IC50 of 0.17 nM and the low affinity site had an IC50 of 12.9 nM Adrenomedullin did not discriminate between these two sites in displacement studies, and had an IC50 of 14.5 nM.

Figure 4.

Displacement of [125I]-amylin by amylin and adrenomedullin in vas deferens membranes. Values are means±s.e.means of three determinations.

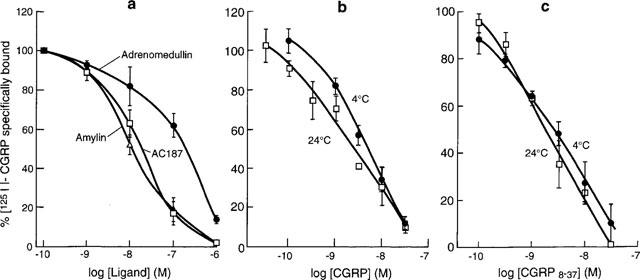

Radioligand binding studies with [125I]-CGRP

[125I]-CGRP bound with high affinity to a single class of sites (nH=0.77±0.17, n=3) on vas deferens with a capacity of 114 fmol receptor mg−1 protein (Table 1). In agreement with previous studies, CGRP8–37 was a potent inhibitor of this binding, in spite of being a very weak antagonist in functional studies. Rat amylin and AC187 were over an order of magnitude less potent than CGRP, and adrenomedullin was about two orders of magnitude less potent than CGRP (Table 1, Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

Displacement of [125I]-CGRP in vas deferens membranes. (a) Displacement by adrenomedullin, AC187 and amylin. Effects of temperature on the displacement by (b) CGRP and (c) CGRP8–37. Values are means±s.e.means of 3–4 determinations.

In order to investigate further the anomalous behaviour of CGRP8–37 binding, the temperature dependency of its binding was investigated. The above experiments were carried out at 4°C, following published procedures (Dennis et al., 1989). However, the functional assays were carried out at 37°C. It proved difficult to obtain reproducible binding data at 37°C, but binding was possible at 24°C (Figure 5b and c). For CGRP8–37 pIC50/nH values were 8.78±0.11/0.77±0.17 at 4°C and 8.50±0.13/1.31±0.21 at 24°C. For CGRP itself, pIC50/nH values were 8.73±0.12/0.89±0.20 at 4°C and 8.62±0.13/0.77±0.20 at 24°C. Thus there were no substantial changes to the affinities of either CGRP or CGRP8–37, implying that temperature is not an important factor in modulating ligand-receptor interactions at the CGRP2 receptor subtype'.

Discussion

These results demonstrate the presence of an adrenomedullin receptor on the guinea-pig vas deferens. This paper also presents new evidence as to the properties of the distinctive CGRP2-type receptor found on this tissue.

Adrenomedullin inhibited electrically stimulated contractions of the vas deferens in a similar manner to CGRP. Further characterization of this response by functional assays was inconclusive. CGRP8–37 failed to block the adrenomedullin response, but it would be expected to be inactive at both CGRP2 and adrenomedullin receptors. Adrenomedullin22–52 has been reported selectively to antagonize adrenomedullin in some tissues e.g. NG108-15 neuroblastoma cells (Zimmermann et al., 1996). However, in-vivo it seems much less effective (Champion et al., 1997; Santiago et al., 1995). In the vas deferens it was active by itself in inhibiting electrically stimulated contractions, and whilst it could additionally antagonize the response to adrenomedullin, it had very similar effects on the responses to CGRP and to some extent, amylin. Whilst inspection of Figure 1 suggests that adrenomedul lin22–52 might be acting non-competitively against CGRP and adrenomedullin, it is difficult to be certain that a true maximum to those two peptides had been established in the presence of the antagonist. AC187 was also inconclusive. This was previously reported to have no effect on the response to CGRP but to block the actions of amylin. This caused a small but non-significant shift in the concentration-response curve to adrenomedullin, but it was not possible to use it at higher concentrations to confirm this response. Broadly similar results have been observed on Rat 2 cells, where AC187 was only a weak antagonist at 10 μM against adrenomedullin (D.M.S. & H.A. Coppock, unpublished observations).

Radioligand binding did yield more conclusive data. It was possible to measure specific binding to both CGRP and adrenomedullin in the vas deferens. However these yielded very different results. The binding site labelled by [125I]-adrenomedullin bound CGRP and amylin with over 200 fold lower affinities compared to adrenomedullin; the converse was found to be true for the binding site labelled with [125I]-CGRP. The capacities of the two sites are also very different. Thus the binding data strongly suggests that CGRP and adrenomedullin interact with distinct sites in the vas deferens.

The adrenomedullin binding data resembles that previously observed with this radioligand where a number of studies have shown that CGRP is at least two orders of magnitude less potent than adrenomedullin (e.g. Coppock et al., 1996; Owji et al., 1995: Zimmermann et al., 1996; Upton et al., 1997). Little comparative work has been done on adrenomedullin and amylin, but what data does exist is again broadly in line with this study, showing that amylin is substantially less potent than adrenomedullin (Zimmermann et al., 1996; Owji et al., 1995). The affinity of AC187 is also in line with that found by radioligand binding on Rat 2 cells. The lack of a specific effect of adrenomedullin22–52 in contrast to some other reports might argue for heterogeneity amongst adrenomedullin receptors. However, caution is needed, since the compound has only been used in comparatively few studies and the data in the present study indicates that it is important to determine its specificity if it does antagonize adrenomedullin.

The nature of the CGRP2 receptor in the vas deferens is curious. Our data confirm what has previously been reported; that although CGRP8–37 is a weak antagonist in functional studies on this tissue, it binds with high affinity in radioligand binding studies (Dennis et al., 1990; Quirion et al., 1992). In previous studies, the radioligand binding was carried out at 4°C in a low ionic strength buffer. As these conditions are very different from those used in functional studies, it was important to check whether or not they influenced the affinity for CGRP8–37; temperature effects have been reported for the binding of this compound to CGRP1 receptors expressed in rat L6 myocytes (Poyner et al., 1992). Clearly, the data in our study show that temperature or buffer composition are unlikely to play a significant role in determining the affinity of CGRP8–37 to CGRP2-type receptors. The anomaly could be an artefact caused by the iodination of CGRP, altering its selectivity. It may also be that some very labile accessory protein (lost during the course of membrane preparation) is responsible for promoting the low antagonist-affinity form of the CGRP2 receptor. The recent description of RAMP which is required for expression of CGRP binding by CRLR may be an interesting precedent for this type of interaction (McLachtie et al., 1998). However, it should be stressed that the molecular nature of the CGRP2 receptor is unknown.

A second interesting feature about the CGRP2 receptor in the vas deferens is its selectivity for CGRP over other peptides; adrenomedullin in particular has a low affinity. This contrasts with a number of binding studies carried out on CGRP1-like receptors. In rat L6 cells, human SK-N-MC cells and HEK293 cells permanently transfected with CRLR, the relative potency order for displacement of [125I]-CGRP binding is CGRP> adrenomedullin>amylin (Poyner et al., 1992; Coppock et al., 1996; Vine et al., 1996; Han et al., 1997). Further work is required to establish whether or not this might be a diagnostic feature for CGRP2 receptors, but our preliminary data on human Col 29 cells which express a CGRP2 receptor indicates that adrenomedullin has an EC50 at least 100 fold lower than that for CGRP. Of course, if the CGRP8–37 affinity at this receptor as determined by radioligand binding does not match that measured in functional assays, it cannot be excluded that these other peptides may show a similar phenomenon. However, the concept that the CGRP2 receptor shows pronounced selectivity for CGRP over other peptides is consistent with our functional data reported here and previously (Tomlinson & Poyner, 1996).

The receptor at which amylin exerts its action remains to be determined. The profile of the binding site labelled by [125I]-amylin is distinct from that labelled by CGRP or adrenomedullin. Furthermore, amylin shows poor ability to displace both [125I]-adrenomedullin and [125I]-CGRP. In the contractile studies adrenomedullin22–52 appeared to be less effective against amylin than adrenomedullin or CGRP. The simplest conclusion is that amylin has an independent receptor. The lack of effects of AC187 suggest that amylin is not acting at its C3 binding site. The peripheral amylin binding site in the lung has a higher affinity for adrenomedullin compared to amylin (and may in fact be identical with the adrenomedullin receptor of that tissue; Owji et al., 1995), but this does not fully match the binding profile found in this study. However, the issue is complicated by the presence of multiple binding sites for [125I]-amylin. The question of which receptor or receptors amylin interacts with will probably only be solved once the sequences of these receptors become available.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Royal Society and the Wellcome Trust. GMT was supported by a studentship from the MRC.

Abbreviations

- CGRP

calcitonin gene-related peptide

- CRLR

calcitonin receptor-like receptor

- RAMP

receptor activity modifying protein

References

- AIYAR N., BAKER E., MARTIN J., PATEL A., STADEL J.M., WILLETTE R.N., BARONE F.C. Differential Calcitonin-Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) and Amylin Binding-Sites in Nucleus-Accumbens and Lung - Potential models for studying CGRP/Amylin Receptor Subtypes. J. Neurochem. 1995;65:1131–1138. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65031131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AIYAR N., RAND K., ELSHOURBAGY N.A., ZENG Z.Z., ADAMOU J.E., BERGSMA D.J., LI Y. A cDNA encoding the Calcitonin-Gene-Related Peptide Type-1 Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:11325–11329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEAUMONT K., PITTNER R.A., MOORE C.X., WOLFE-LOPEZ D., PRICKETT K.S., YOUNG A.A., RINK T.J. Regulation of muscle glycogen metabolism by CGRP and amylin; CGRP receptors not involved. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:713–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14991.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BHOGAL R., SMITH D.M., BLOOM S.R. Investigation and characterisation of binding sites for islet amyloid polypeptide in rat membranes. Endocrinology. 1992;130:906–913. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.2.1310282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BHOGAL R., SMITH D.M., PURKISS P., BLOOM S.R. Molecular identification of binding sites for calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) in mammalian lung; species variation and binding of truncated CGRP and IAPP. Endocrinology. 1993;133:2351–2361. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.5.8404688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAMPION H.C., SANTIAGO J.A., MURPHY W.A. Adrenomedullin-(22-52) antagonises the vasodilator responses to calcitonin gene-related peptide but not adrenomedullin in the cat. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:R234–R242. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.1.R234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN W.-J., ARMOUR S., WAY J., CHEN G., WATSON C., IRVING P., COBB J., KADWELL S., BEAUMONT K., RIMELE T., KENAKIN T. Expression cloning and receptor pharmacology of human calcitonin receptors from MCF-7 cells and their relationship to amylin receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;52:1164–1175. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.6.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COPPOCK H.A., OWJI A.A., BLOOM S.R., SMITH D.M. A rat skeletal muscle cell line (L6) expresses specific adrenomedullin binding sites but activates adenylyl cyclase via calcitonin gene-related peptide receptors. Biochem. J. 1996;318:241–245. doi: 10.1042/bj3180241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENNIS T.B., FOURNIER A., CADIUEX A., POMERLEAU F., JOLICOEUR F.B., QUIRION R. hCGRP8-37, a calcitonin gene-related peptide antagonist revealing CGRP receptor heterogeneity in brain and periphery. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;254:123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENNIS T.B., FOURNIER A., STPIERRE S., QUIRION R. Structure-activity profile of calcitonin gene-related peptide in peripheral and brain tissues. Evidence for receptor multiplicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989;251:718–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAN Z.Q., COPPOCK H.A., SMITH D.M., VAN NOORDEN S., MAKGOBA M.W., NICHOLL C.G., LEGON S. The interaction of CGRP and adrenomedullin with a receptor expressed in the rat pulmonary vascular endothelium. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 1997;18:267–272. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0180267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITAMURA K., KANGAWA K., KAWAMOTO M., ICHIKI Y., NAKAMURA S., HISAYUKI M., ETO T. Adrenomedullin, a novel hypotensive peptide isolated from human phaeochromocytoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993a;192:553–560. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITAMURA K., SAKATA J., KANGAWA K., KOJIMA M., MATSUO H., ETO T. Cloning and isolation of cDNA encoding a precursor for human adrenomedullin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993b;194:720–725. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIN B., GAO Y.G., CHANG J.K., HEATON J., HYMAN A., LIPPTON H. An adrenomedullin fragment retains the systemic vasodepressor activity of rat adrenomedullin. European J. Pharmacol. 1994;260:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLACHTIE L.M., FRASER N.J., MAIN M.J., WISE A., BROWN J., THOMPSON N., SOLARI R., LEE M.G., FOORD S.M. RAMPs regulate the transport and ligand specificity of the calcitonin receptor-like receptor. Nature. 1998;393:333–339. doi: 10.1038/30666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OWJI A.A., SMITH D.M., COPPOCK H.A., MORGAN D.G.A., BHOGAL R., GHATEI M.A., BLOOM S.R. An abundant and specific binding site for the novel vasodilator adrenomedullin in the rat. Endocrinology. 1995;136:2127–2134. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.5.7720662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POYNER D.R. Effects of temperature on the binding of calcitonin gene-related peptide and analogues to the Guinea-pig cerebellum and vas deferens. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997a;120:235P. [Google Scholar]

- POYNER D.R. Molecular pharmacology of receptors for calcitonin gene-related peptide, amylin and adrenomedullin. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1997b;25:1032–1036. doi: 10.1042/bst0251032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POYNER D.R. The pharmacology of receptors for calcitonin gene-related peptide and amylin. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1995;16:424–428. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POYNER D.R. Calcitonin gene-related peptide; multiple functions, multiple receptors. Pharm. Ther. 1992;56:23–51. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(92)90036-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POYNER D.R., ANDREW D., BROWN D., BOSE C., HANLEY M.R. Pharmacological characterization of a receptor for calcitonin gene-related peptide on rat L6 skeletal myocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;105:441–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUIRION R., VAN ROSSUM D., DUMONT Y., STPIERRE S., FOURNIER A. Characterization of CGRP1 and CGRP2 receptors. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1992;657:88–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb22759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANTIAGO J.A., GARRISON E.A., PURNELL W.L. Comparison of responses to adrenomedullin and adrenomedullin analogues in the mesenteric vascular bed of the cat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;272:115–118. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)00693-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEXTON P.M., MCKENZIE J.S., MENDELSOHN F.A.O. Evidence for a new subclass of calcitonin gene-related peptide binding-site in rat-brain. Neurochem. Int. 1988;12:323–325. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(88)90171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEXTON P.M., PERRY K.J., CHRISTOPOULOS G., MORFIS M., TILAKARATNEWhat makes an amylin receptor 1999. In The CGRP family: CGRP, amylin and adrenomedullin, eds., Poyner, D.R., Brain, S.D. and Marshall, I. Austin, Texas, Landes Bioscience

- TOMLINSON A.E., POYNER D.R. Multiple receptors for CGRP and amylin on guinea pig vas deferens and vas deferens. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:1362–1368. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UPTON P.D., AUSTIN C., TAYLOR G.M., NANDHA K.A., CLARK A.J., GHATEI M.A., BLOOM S.R., SMITH D.M. Expression of adrenomedullin (ADM) and its binding sites in the rat uterus: increased numbers of binding sites and ADM messenger ribonucleic acid in 20-day old pregnant rats compared with nonpregnant rats. Endocrinology. 1997;138:2508–2514. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.6.5186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VEALE P., BHOGAL R., MORGAN D., SMITH D., BLOOM S. The presence of islet amyloid polypeptide/calcitonin gene-related peptide/salmon calcitonin binding-sites in the rat nucleus-accumbens. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994;262:133–141. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VINE W., BEAUMONT K., GEDULIN B., PITTNER R., MOORE C.-X., RINK T.J., YOUNG A.A. Comparison of the in-vitro and in-vivo pharmacology of adrenomedullin, CGRP and amylin in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996;314:115–121. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00544-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WITHERS D.J., COPPOCK H.A., SEUFFERLEIN T., SMITH D.M., BLOOM S.R., ROZENGURT E. Adrenomedullin stimulates DNA synthesis and cell proliferation via elevation of cAMP in Swiss 3T3 cells. FEBS Lett. 1996;378:83–87. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01427-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZIMMERMANN U., FISCHER J.A., FRE K., FISCHER A.H., REINSCHEID R.K., MUFF R.A. Identification of adrenomedullin receptors in cultured rat astrocytes and in neuroblastoma X glioma hybrid cells. Brain Res. 1995;724:238–245. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00337-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]