Abstract

We investigated the cardiovascular effects of rilmenidine, moxonidine and clonidine in conscious wild-type and D79N α2A-adrenoceptor mice. The in vitro pharmacology of these agonists was determined at recombinant (human) α2-adrenoceptors and at endogenous (dog) α2A-adrenoceptors.

In wild-type mice, rilmenidine, moxonidine (100, 300 and 1000 μg kg−1, i.v.) and clonidine (30, 100 and 300 μg kg−1, i.v.) dose-dependently decreased blood pressure and heart rate.

In D79N α2A-adrenoceptor mice, responses to rilmenidine and moxonidine did not differ from vehicle control. Clonidine-induced hypotension was absent, but dose-dependent hypertension and bradycardia were observed.

In wild-type mice, responses to moxonidine (1 mg kg−1, i.v.) were antagonized by the non-selective, non-imidazoline α2-adrenoceptor antagonist, RS-79948-197 (1 mg kg−1, i.v.).

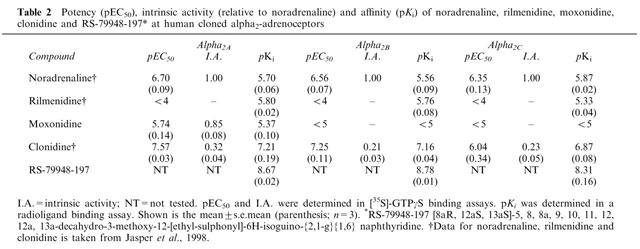

Affinity estimates (pKi) at human α2A-, α2B- and α2C-adrenoceptors, respectively, were: rilmenidine (5.80, 5.76 and 5.33), moxonidine (5.37, <5 and <5) and clonidine (7.21, 7.16 and 6.87). In a [35S]-GTPγS incorporation assay, moxonidine and clonidine were α2A-adrenoceptor agonists (pEC50/intrinsic activity relative to noradrenaline): moxonidine (5.74/0.85) and clonidine (7.57/0.32).

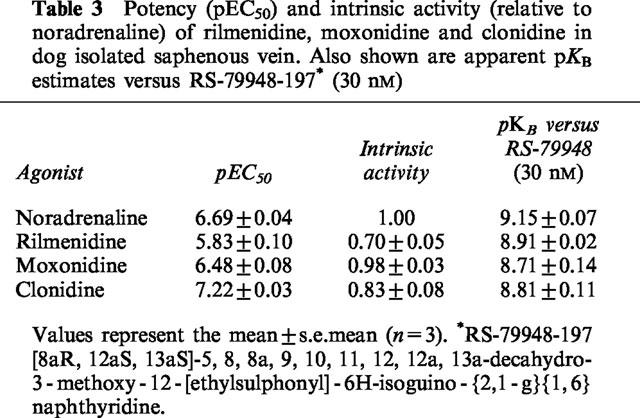

In dog saphenous vein, concentration-dependent contractions were observed (pEC50/intrinsic activity relative to noradrenaline): rilmenidine (5.83/0.70), moxonidine (6.48/0.98) and clonidine (7.22/0.83). Agonist-independent affinities were obtained with RS-79948-197.

Thus, expression of α2A-adrenoceptors is a prerequisite for the cardiovascular effects of moxonidine and rilmenidine in conscious mice. There was no evidence of I1-imidazoline receptor-mediated effects. The ability of these compounds to act as α2A-adrenoceptor agonists in vitro supports this conclusion.

Keywords: Rilmenidine, moxonidine, clonidine, α2-adrenoceptors, imidazoline receptors, RS-79948-197

Introduction

It is well established that α2-adrenoceptor agonists produce hypotension by central activation of α2-adrenoceptors (Schmitt et al., 1973; Timmermans et al., 1981; Bousquet, 1981; van Zwieten, 1986). Centrally-acting α2-adrenoceptor agonists suppress sympathetic outflow, thereby reducing systemic blood pressure and heart rate. It has been proposed that a non-adrenoceptor, designated as the I1-imidazoline site, can also evoke a centrally-mediated hypotension (Tibirica et al., 1991; Head et al., 1993; Buccafusco et al., 1995). Putative I1-imidazoline receptors reportedly have many characteristics of functional receptors (Ernsberger & Haxhiu, 1997).

These observations have led to the proposal that selective I1-imidazoline receptor agonists might form a second generation of centrally-acting antihypertensive drugs devoid of the side effects associated with α2-adrenoceptor agonists (e.g. sedation and dry mouth). The first representatives of this new class of antihypertensive agents are the putative selective I1-imidazoline receptor agonists rilmenidine and moxonidine (Ernsberger et al., 1993; Yu & Frishman, 1996; Reis, 1996). The selectivity of these compounds for putative I1-imidazoline receptors is based on both in vitro radioligand binding studies as well as in vivo studies in anaesthetized and conscious animals (Haxhiu, 1992; Ernsberger et al., 1995; Chan & Head, 1996;Bousquet, 1997).

The hypothesis that activation of central I1-imidazoline receptors produces hypotension is controversial (Eglen et al., 1998). Numerous investigators have concluded that the antihypertensive effects of imidazoline agonists are mediated via central activation of α2-adrenoceptors (Hieble & Kolpak, 1993; Urban et al., 1994, 1995; Stornetta et al., 1995; Vayssettes-Courchay et al., 1996). Moreover, MacMillan et al. (1996), using D79N α2A-adrenoceptor transgenic mice (functional α2A-adrenoceptor ‘knock-out' mice), demonstrated that α2A-adrenoceptors mediate the hypotensive response to the imidazoline α2-adrenoceptor agonists, brimonidine (UK-14,304) and dexmedetomidine, with no evidence for an I1-imidazoline receptor-mediated hypotension. Brimonidine and dexmedetomidine, however, have been reported to be selective for α2-adrenoceptors over I1-imidazoline receptors (Yu & Frishman, 1996) and studies with rilmenidine and moxonidine have yet to be reported.

In the present study we have evaluated the cardiovascular effects of the putative I1-imidazoline receptor-selective agonists rilmenidine and moxonidine and the mixed α2-adrenoceptor/putative I1-imidazoline receptor agonist clonidine in both conscious wild-type mice and in D79N α2A-adrenoceptor transgenic mice. In wild-type mice, the effects of moxanidine were also studied in the absence and presence of the non-imidazoline, non-selective, α2-adrenoceptor antagonist, RS-79948-197 ([8aR,12aS,13aS]-5,8,8a,9,10,11,12,12a,13a-decahydro -3 -methoxy -12 -[ethylsulphonyl]-6H-isoguino-{2,1-g}{1,6} naphthyridine, hereafter referred to as RS-79948; Milligan et al., 1997), thereby allowing the assessment of the role of α2-adrenoceptors. Finally, the in vitro activity of these agonists was also evaluated at recombinant human and endogenous dog α2-adrenoceptors. The data are consistent with rilmenidine, moxonidine and clonidine acting as α2-adrenoceptor agonists.

A preliminary account of this data has been presented (Zhu et al., 1997).

Methods

In vivo studies

Animals

Male mice (22–34 g) were used for all studies. Mutant α2A-adrenoceptor mice, 129Sv-(D79N)Adra2a strain, were obtained from Dr Leigh MacMillan of Vanderbilt University (Nashville, TN, U.S.A.) and subsequently bred in-house at Roche Bioscience (Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.) Wild-type mice, 129Sv strain, were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, U.S.A.). All mice received a standard diet with water and were housed at 22±1°C on a 12 h light/dark cycle.

Surgery

Mice were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbitone (50–60 mg kg−1, i.p.). The left carotid artery and jugular vein were isolated and cannulated with PE-10 tubing filled with heparinized saline (50 u ml−1). Both cannulae were tunnelled subcutaneously to the back of the neck and exteriorized into a fabric pocket secured to the back of the mouse with 3-0 silk ligatures. The incision site was closed with 4-0 silk ligatures and the carotid artery cannula was flushed with heparinized saline (100 u ml−1). Mice were placed on a warm heating pad until they regained consciousness and were then returned to normal housing. Mice were allowed to recover from anaesthesia and surgery for at least 18 h before commencing studies.

Experimental procedure

A total of 24 mice were used to study the effects of clonidine, rilmenidine and moxonidine in wild-type and D79N α2-adrenoceptor mutant mice (12 wild-type and 12 D79N mutant mice). A Latin Square crossover design was performed for each compound which included four treatments (vehicle, low, middle and high doses) over 4 days with a total of four animals.

On each of four consecutive study days, the mice were placed in restraint boxes and allowed to stabilize for 45–60 min. Vehicle (0.5 ml kg−1 saline; 0.015 ml for a 30 g mouse) or one of three doses of test agonist (dose volume 0.5 ml kg−1) was administered to each mouse via the venous cannula and flushed with 0.03 ml of saline. Therefore, the total volume of saline administered was approximately 0.045 ml for a 30 g mouse. Blood pressure and heart rate were monitored continuously using Gould pressure transducers (p23XL) connected to a Gould MK 200A polygraph (Gould Instrument Systems Inc., Valley View, OH, U.S.A.) and a Buxco (LS20) logging analyzer (Buxco Electronics Inc., North Troy, NY, U.S.A.). Cannulae were flushed with heparinized saline at the end of each experiment and placed back into the fabric pocket. Mice were killed with an overdose of sodium pentobarbitone upon study completion.

The effect of RS-79948 (1 mg kg−1, i.v.) on blood pressure and heart rate responses evoked by a single dose of moxonidine (1 mg kg−1, i.v.) was evaluated in a total of ten mice using a single crossover design in two separate groups (five mice per group). Vehicle/vehicle and RS-79948/vehicle were studied in the first group while vehicle/moxonidine and RS-79948/moxonidine were studied in the second group. The crossover occurred 48 h after the first study day to ensure adequate systemic elimination of RS-79948. Mice were dosed with moxonidine or vehicle 15 min after administration of RS-79948.

In vitro studies

Membrane preparation

Membranes for both [35S]-GTPγS binding and radioligand displacement assays were prepared from HEK 293 cells expressing human α2A-, α2B- and α2C-adrenoceptors as previously described (Jasper et al., 1998).

[35S]-GTPγS binding assay

The methods of Tian et al. (1994) were modified as follows: membranes were thawed and diluted with buffer (mM): (Tris-HCl 50, MgCl2 5, NaCl 100, EDTA 1, dithiothreitol 1, propraonol 1 μM, GDP 2 μM, pH 7.4 at 25°C). Membrane protein (4–10 μg) was incubated with 0.3 nM [35S]-GTPγS and agonist for 60 min at 25°C. The reactions were terminated by vacuum filtration over GF/B glass fibre filter pretreated with 0.5% BSA. Filters were washed with ice cold wash buffer (mM): (Tris-HCl 50, MgCl2 5, NaCl 100 pH 7.5 at 4°C) and incorporated radioactivity was determined using liquid scintillation counting.

Agonist-induced [35S]-GTPγS dose-response curves were analysed by non-linear, least squares analysis (GraphPad Prism; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). Potency values are expressed as pEC50 values (−log10 concentration of agonist required to give 50% of its own maximal stimulation). The maximal stimulation (intrinsic activity) achieved for each compound was expressed as a percentage of the maximal noradrenaline response. Data are expressed as means±s.e.mean from three experiments.

Radioligand displacement assay

Membranes were thawed at room temperature and diluted in assay buffer (mM): Tris 50, EDTA 1, NaCl 150, MgCl2 2, and guanyl-5′-yl imidodiphosphate 100 μM, pH 7.4 at 25°C) to a final concentration of 5–10 μg protein/assay tube. For binding isotherms, membranes were incubated with 0.01–5 nM [3H]-MK-912 in the presence or absence of 1 μM RX821002 for 60 min at room temperature. Binding was terminated by vacuum filtration over GF/B glass fibre filter using a Packard Top Count 96 well cell harvester. The tubes were rinsed three times with 1 ml ice cold 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4 and bound radioactivity determined by liquid scintillation counting. For radioligand displacement assays, varying concentrations of test ligand were incubated with 0.3–0.5 nM [3H]-MK-912 (α2A- and α2B-adrenoceptors) or 0.03–0.05 nM [3H]-MK-912 (α2C-adrenoceptor) and binding performed as above.

For each compound tested in radioligand binding studies, the concentration producing 50% inhibition of binding (IC50) and Hill slope was determined using iterative curve fitting techniques. The equilibrium dissociation constant (Ki) of each compound was determined according to the method of Cheng & Prusoff (1973). The negative logarithm of the Ki (pKi) is presented.

Dog isolated saphenous vein

α2A-Adrenoceptor mediated contraction of dog saphenous vein was assessed as described by MacLennan et al. (1997). Saphenous veins were removed from male mongrel dogs (10–15 kg), previously killed by an overdose of sodium pentobarbitone. Isometric tension changes were measured from ring preparations suspended within 20 ml organ baths filled with Krebs solution maintained at 37°C and aerated with 95% O2/5% CO2. The Krebs solution had the following composition (mM): NaCl 118.41, NaHCO3 25.00, KCl 4.75, KH2PO4 1.19, MgSO4 1.19, glucose 11.10 and CaCl2 2.50. Cocaine, corticosterone (each 30 μM) EDTA (23 μM), (±)-propranolol (1 μM) and nitrendipine (0.1 μM) were added to the Krebs solution to block neuronal and non-neuronal uptake, auto-oxidation of catecholamines, β-adrenoceptors and L-type calcium channels, respectively.

α1-Adrenoceptors were inactivated by exposing the tissues to phenoxybenzamine (3 μM for 30 min), in the presence of the α2-adrenoceptor antagonist rauwolscine (1 μM) to protect α2A-adrenoceptors. Antagonists were washed out by four exchanges of the Krebs solution at 5 min intervals. In each tissue two agonist concentration-effect (E/[A]) curves were constructed. In some experiments the second curve was constructed in the presence of an antagonist which had been added 60 min previously.

Logistic curve fitting and analysis of antagonism

The Hill equation was fitted to individual E/[A] curves:

|

in which E, α, [A]50 and nH are effect, upper-asymptote, mid-point location and slope parameters respectively. Location parameters were actually estimated as logarithms (−log10 [A]50). Antagonist affinities (apparent pKB) were estimated using the equation

provided that the shift produced by the antagonist was parallel and making the assumption of simple competitive antagonism, i.e. that n was unity.

Statistical analysis

In vivo data was analysed using Buxco LAPP1 software. A blood pressure and heart rate value was obtained every 5 min for 2 h after compound administration. Change from baseline (measurement at time 0) was calculated. The average blood pressure and heart rate changes were calculated for the following four time intervals: (1) 5–30 min, (2) 35–60 min, (3) 65–90 min and (4) 95–120 min. Statistical analyses were conducted in which each dose of test compound was compared to vehicle control using ANOVA with three main effects: treatment, day and animal. Subsequent pairwise comparisons were performed using Fisher's LSD test. Bonferroni's adjustment for multiple comparisons was made if the overall difference was not significant. Student's t-tests or Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests were used to determine at what times the average changes in blood pressure and heart rate were significant compared to vehicle control. A Student's t-test was used when data assumptions (normality and homogenous variance) were not violated. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Data were analysed differently for the study investigating the effect of RS-79948 on moxonidine-induced blood pressure and heart rate responses. As detailed above, baseline changes in blood pressure and heart rate were calculated after administration of moxonidine. Student t-tests (parametric) or Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests (nonparametric) were used to compare the moxonidine data with time-matched vehicle controls. P values less than 0.05 were regarded as significant.

Statistical analysis of in vitro data, when appropriate, were performed using a Student's t-test, with P values less than 0.05 regarded as statistically significant.

Values reported in the text represent the mean±s.e.mean.

Drugs and solutions

The following compounds were purchased: (−)-noradrenaline bitartrate, (±)-propranolol hydrochloride and Krebs solution (Sigma, MO, U.S.A.); clonidine hydrochloride (Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp., CA, U.S.A.); rauwolscine hydrochloride and phenoxybenzamine hydrochloride (ICN Pharmaceuticals, CA, U.S.A.). [35S]-GTPγS and [3H]-MK-912 were obtained from New England Nuclear (Boston, MA, U.S.A.). Rilmenidine hemisumarate, moxonidine, nitrendipine hydorchloride and RS-79948-197 ([8aR, 12aS, 13aS]-5,8,8a,9,10,11,12, 12a,13a-decahydro-3-methoxy-12-{ethylsulphonyl}-6H-isoguino-{2,1-g}{1,6} naphthyridine) were synthesized at Roche Bioscience (Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.).

All compounds were dissolved in saline (in vivo studies) or water (in vitro studies) with the exception of phenoxybenzamine (2 mM) and nitrendipine (1 mM) which were dissolved in absolute ethanol and diluted in water.

For in vivo studies, moxonidine was pre-dissolved in one drop of 1 N HCl and made to volume in deionized water. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 using 1 N NaOH. Appropriate stock solutions were made to allow a final dose volume of 0.5 ml kg−1.

Results

In vivo studies

Cardiovascular effects of vehicle, rilmenidine, moxonidine and clonidine

Initial baseline values for mean blood pressure and heart rate, respectively, were as follows: wild-type (n=12), 146±2 mmHg and 489±30 beats min−1; D79N α2A-adrenoceptor mice (n=12), 155±3 and 489±27 beats min−1. Baseline mean blood pressure of D79N α2A-adrenoceptor mice was significantly higher than wild-type mice (P<0.05). Baseline heart rate was not significantly different between the two groups.

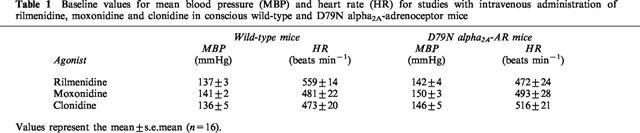

The mean baseline values (n=16) for blood pressure and heart rate over the 4-day crossover studies are given in Table 1. For reasons unknown, the mean baseline blood pressure values for each 4-day crossover study were consistently lower than the initial baseline values given above. Possible explanations include a carry-over effect from drug treatment, recovery from surgery and acclimatization of the mice to the experimental protocol, including restraint.

Table 1.

Baseline values for mean blood pressure (MBP) and heart rate (HR) for studies with intravenous administration of rilmenidine, moxonidine and clonidine in conscious wild-type and D79N alpha2A-adrenoceptor mice

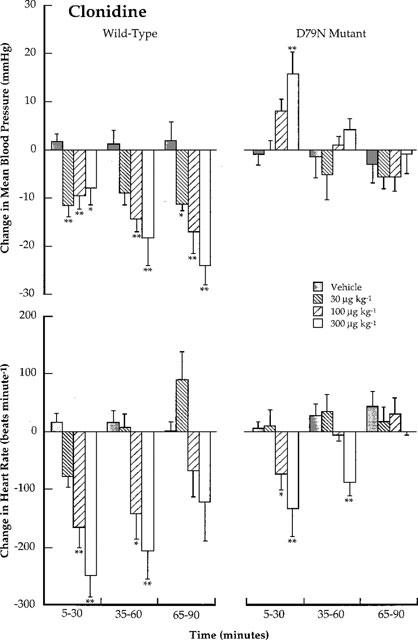

In both wild-type and D79N α2A-adrenoceptor mice, intravenous administration of vehicle induced a transient pressor response. The initial pressor response induced by injection of rilminidine, moxonidine and clonidine did not differ from vehicle control in wild-type mice (data not shown). In D79N α2A-adrenoceptor mice, only the initial pressor effect following administration of clonidine (300 μg kg−1, i.v.) was significantly greater than vehicle (P<0.05; data not shown). This dose of clonidine produced a prolonged pressor response compared to vehicle control (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Conscious wild-type and D79N mutant α2A-adrenoceptor mice: Comparison of the effects of clonidine (30, 100 and 300 μg kg−1; i.v.) on changes in mean blood pressure (mmHg) and heart rate (beats min−1). Each bar represents the mean value with s.e.mean for data collected at 5 min intervals over 30 min time periods. The mean values are obtained from four mice using a Latin square crossover design. Blood pressure and heart rate changes are compared with those caused by vehicle using Student t-tests. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

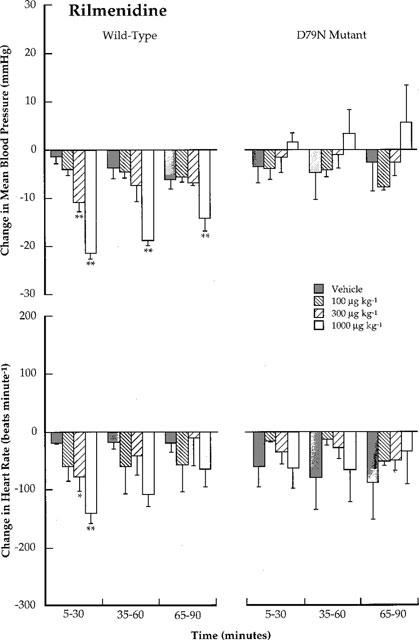

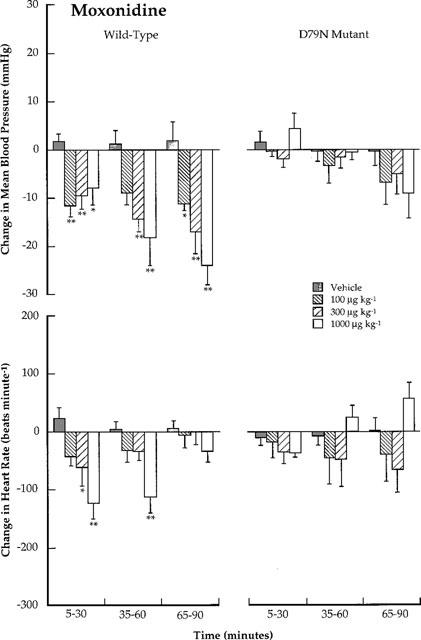

In wild-type mice, rilmenidine, moxonidine and clonidine caused a prolonged, dose-dependent hypotension and bradycardia (Figures 1, 2 and 3). The hypotensive response produced by clonidine, moxonidine and the high dose of rilmenidine lasted the duration of the 2 h study. In contrast, decreases in heart rate returned to baseline levels within 2 h.

Figure 1.

Conscious wild-type and D79N mutant α2A-adrenoceptor mice: Comparison of the effects of rilmenidine (100, 300 and 1000 μg kg−1; i.v.) on changes in mean blood pressure (mmHg) and heart rate (beats min−1). Each bar represents the mean value with s.e.mean for data collected at 5 min intervals over 30 min time periods. The mean values are obtained from four mice using a Latin square crossover design. Blood pressure and heart rate changes are compared with those caused by vehicle using Student t-tests. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Figure 2.

Conscious wild-type and D79N mutant α2A-adrenoceptor mice: Comparison of the effects of moxonidine (100, 300 and 1000 μg kg−1; i.v.) on changes in mean blood pressure (mmHg) and heart rate (beats min−1). Each bar represents the mean value with s.e.mean for data collected at 5 min intervals over 30 min time periods. The mean values are obtained from four mice using a Latin square crossover design. Blood pressure and heart rate changes are compared with those caused by vehicle using Student t-tests. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

In D79N α2A-adrenoceptor mice, the hypotension and bradycardia produced by rilmenidine and moxonidine in wild-type mice were not different from vehicle control (Figures 1 and 2). For moxonidine, there appeared to be a delayed hypotensive response (80–105 min post-dose), although the decrease in blood pressure was not statistically different from the vehicle condition. To investigate further the possibility that putative I1-imidazoline receptors may mediate a delayed hypotensive response, a separate set of experiments were conducted in D79N α2A-adrenoceptor mice in which the effect of vehicle and moxonidine (1 mg kg−1, i.v.) was evaluated in a non-crossover study (n=5 for vehicle and moxonidine). In this study there was no difference between vehicle and moxonidine, even at later time points (>90 min; data not shown).

The effect of clonidine in D79N α2A-adrenoceptor mice was more complex. The hypotensive response observed in wild-type mice was absent and a dose-dependent, statistically-significant pressor response was observed at 100 and 300 μg kg−1 doses (P<0.05 and 0.01 respectively; Figure 3). Compared to the vehicle effect, the pressor response at these doses was longer in duration (⩾30 min). As in wild-type mice, clonidine produced dose-dependent decreases in heart rate (P<0.05 and 0.01 at 100 and 300 μg kg−1 doses, respectively).

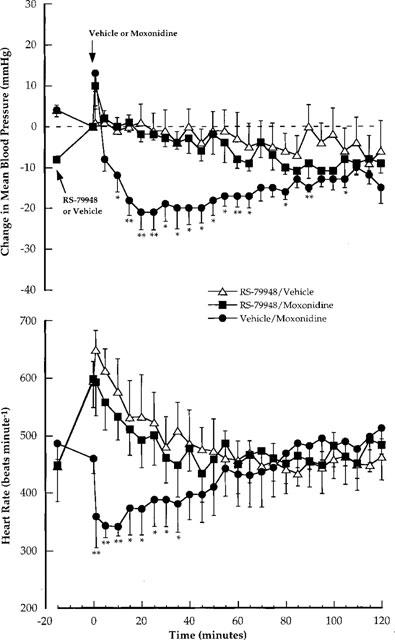

Effect of RS-79948 on moxonidine-induced blood pressure and heart rate changes in conscious wild-type mice

Initial baseline values for mean blood pressure and heart rate in conscious vehicle- and RS-79948-treated (1 mg kg−1, i.v.) wild-type mice were as follows: vehicle-treated (n=10), 149±2.9 mmHg and 498±22.3 beats min−1, RS-79948-treated (n=10), 147.4±3.1 and 597.7±28.2 beats min−1. Thus, baseline heart rate was significantly higher in mice treated with RS-79948 (P<0.05).

The effect of RS-79948 on moxonidine-induced hypotension and bradycardia is shown in Figure 4. It should be noted that blood pressure is plotted as a change from baseline whereas heart rate is plotted as absolute values so as to account for the effect of RS-79948 on baseline heart rate. As demonstrated in the first crossover study in wild-type mice (see Figure 2), moxonidine (1 mg kg−1, i.v.) alone produced a moderate hypotension and bradycardia. Comparison of the RS-79948/vehicle and RS-79948/moxonidine groups shows that moxonidine failed to lower blood pressure or heart rate after pretreatment with RS-79948.

Figure 4.

Conscious wild-type mice: Comparison of the effects of moxonidine (1 mg kg−1; i.v.) on changes in mean blood pressure (mmHg) and absolute values of heart rate (beats min−1) in the absence and presence of RS-79948 (1 mg kg−1; i.v.). Absolute values are shown for heart rate to account for baseline increases induced by RS-79948. Each point represents the mean value with s.e.mean. The mean data are obtained from two, single crossover studies with five mice in each study. The effect of moxonidine is compared with the appropriate vehicle (vehicle/vehicle or RS-79948/vehicle) using Student t-tests or Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests. The data for vehicle/vehicle is not shown. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

In vitro studies

None of the drug vehicles influenced responses for studies using either human recombinant α2-adrenoceptors or native α2-adrenoceptors in dog isolated saphenous vein.

Studies with human recombinant α2-adrenoceptors

The affinity of moxonidine at human cloned α2A-, α2B- and α2C-adrenoceptors labelled with [3H]-MK-912 was 5.37±0.10, <5 and <5, respectively. Affinity estimates for noradrenaline, rilmenidine and clonidine have been obtained previously in this assay (Jasper et al., 1998). This assay was also used to estimate the affinity of the non-imidazoline α2-adrenoceptor antagonist RS-79948. Affinity estimates for all of these compounds are given in Table 2. The selectivity of RS-79948 for α2-adrenoceptors over α1-adrenoceptors was confirmed by obtaining affinity estimates at human cloned α1A-, α1B- and α1D-adrenoceptors (5.52, 5.76 and 6.53 respectively; personal communication, Dr T.J. Williams, Roche Bioscience, Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.).

Table 2.

Potency (pEC50), intrinsic activity (relative to noradrenaline) and affinity (pKi) of noradrenaline, rilmenidine, moxonidine, clonidine and RS-79948-197* at human cloned alpha2-adrenoceptors

The potency and intrinsic activity (relative to noradrenaline) of moxonidine at human cloned α2A-, α2B- and α2C-adrenoceptors was evaluated in a [35S]-GTPγS incorporation assay. Up to the highest concentration tested (10 μM), moxonidine acted as an agonist only at human α2A-adrenoceptors (pEC50=5.74±0.14; intrinsic activity=0.85±0.08). The potency and intrinsic activity of rilmenidine and clonidine has been reported previously in this assay (Jasper et al., 1998). Clonidine had agonist activity at all three α2-adrenoceptor subtypes whereas rilmenidine was inactive at each subtype at the concentrations tested. The agonist activity of these agonists is summarized in Table 2.

Dog isolated saphenous vein

Noradrenaline, rilmenidine, moxonidine and clonidine all evoked concentration-dependent contractions of dog isolated saphenous vein, a functional α2A-adrenoceptor assay. The rank order of agonist potency was noradrenaline > clonidine > moxonidine > rilmenidine. With regard to intrinsic activity (relative to noradrenaline), moxonidine acted as a full agonist (intrinsic activity=0.98±0.03) whereas the maximal response evoked by clonidine and rilmenidine were 0.83±0.08 and 0.70±0.05, respectively. The potency and intrinsic activity (relative to noradrenaline) of these agonists is summarized in Table 3. Agonist-independent affinity estimates (apparent pKB) were obtained with the non-imidazoline α2-adrenoceptor antagonist RS-79948: rilmenidine (8.91±0.02), moxonidine (8.71±0.14) and clonidine (8.81±0.11), consistent with its affinity for the human cloned α2A-adrenoceptor (see above).

Table 3.

Potency (pEC50) and intrinsic activity (relative to noradrenaline) of rilmenidine, moxonidine and clonidine in dog isolated saphenous vein. Also shown are apparent pKB estimates versus RS-79948-197* (30 nM)

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to ascertain the identity of the receptor(s) mediating the cardiovascular effects, specifically hypotension and bradycardia, of the putative I1-imidazoline receptor-selective agonists rilmenidine and moxonidine in conscious mice. The cardiovascular effects of clonidine were also evaluated since clonidine has been claimed to be a mixed α2-adrenoceptor/I1-imidazoline receptor agonist. The results suggest strongly that rilmenidine, moxonidine and clonidine exert their hypotensive and bradycardic effects in conscious mice exclusively via activation of α2A-adrenoceptors. There was no evidence for the involvement of putative I1-imidazoline receptors. The pharmacology of these agonists at recombinant (human) and endogenous (dog) α2-adrenoceptors in vitro is consistent with this conclusion.

The mouse was ideally suited for this study since this species allowed in vivo evaluation of the pharmacology of rilmenidine and moxonidine in both wild-type and in transgenic animals deficient in functional α2A-adrenoceptors (i.e. D79N α2A-adrenoceptor mice). In D79N transgenic mice, α2A-adrenoceptor function is lost due to a reduction in the density of α2A-adrenoceptors and an uncoupling of expressed receptors from signal transduction pathways (MacMillan et al., 1996). MacMillan et al. (1996) demonstrated that hypotension and bradycardia evoked by intra-arterial administration of brimonidine and dexmedetomidine in wild-type mice were absent in D79N transgenic mice. These authors concluded that the α2A-adrenoceptor subtype plays a critical role in mediating the hypotensive response to α2-adrenoceptor agonists.

The data obtained by MacMillan et al. (1996) in D79N transgenic mice has fueled the debate over the possible role of putative I1-imidazoline receptors in the central control of blood pressure. These data have been interpreted to indicate that imidazoline-based agonists, including brimonidine and dexmedetomidine, mediate there hypotensive effect predominantly, if not exclusively, via activation of α2A-adrenoceptors (MacMillan et al., 1996; MacDonald et al., 1997; Guyenet, 1997). This interpretation assumes that the D79N mutation of the α2A-adrenoceptor did not effect I1-imidazoline sites. An alternative explanation is that putative I1-imidazoline receptor activation is without effect unless α2A-adrenoceptors are simultaneously activated (Guyenet, 1997). Studies in D79N transgenic mice have been criticized by Ernsberger & Haxhiu (1997). These authors contend that brimonidine and dexmedetomidine are inappropriate tools for studying I1-imidazoline receptors because they preferentially activate α2-adrenoceptors and the use of the mouse is inappropriate given that little is known about brain stem I1-imidazoline receptors in this species. It is within the context of these opposing viewpoints that the present study should be considered.

In vivo studies

The agonists used in the present study were chosen on the basis of their selectivity for putative I1-imidazoline receptors. Rilmenidine and moxonidine are claimed to preferentially activate I1-imidazoline receptors over α2-adrenoceptors (Chan et al., 1996; Yu & Frishman, 1996), whereas clonidine is reported to activate both α2-adrenoceptors and putative I1-imidazoline receptors (De Vos et al., 1994). All three agonists produced a dose-dependent, statistically significant decrease in blood pressure and heart rate in wild-type mice (Figures 1, 2 and 3). Clonidine was approximately 3- and 10 fold more potent at evoking hypotension than moxonidine and rilmenidine. This rank order of agonist hypotensive potency closely resembles that demonstrated by Chan & Head (1996) after intravenous administration of these agonists to conscious rabbits.

Rilmenidine and moxonidine did not evoke a statistically significant change (increase or decrease) in blood pressure or heart rate in D79N transgenic mice when compared with in vehicle controls (Figures 1 and 2). For moxonidine, however, there was the appearance of a delayed hypotensive response 80–105 min post-dose (see 65–90 min histograms in Figure 2); a response not evident after administration of rilmenidine. A second study was conducted with a single dose of moxonidine (1 mg kg−1, i.v.) to investigate further the possibility that putative I1-imidazoline receptors may mediate a delayed hypotensive response. In this study there was no difference between vehicle and moxonidine at any time point (n=5; data not shown).

The cardiovascular effect of clonidine in D79N transgenic mice was complex. As with rilmenidine and moxonidine, the hypotensive effect seen in wild-type mice was absent. A dose-dependent pressor response, however, occurred which was greater in magnitude and duration than the effect observed in vehicle-treated mice (Figure 3). The receptor mediating the pressor response to clonidine was not investigated further but it is well established that clonidine is an agonist at both α2B-adrenoceptors (see Table 2) and α1A-adrenoceptors (Minneman et al., 1994). As in wild-type mice, clonidine evoked dose-dependent bradycardia in D79N transgenic mice. This bradycardia could be a reflex response to the clonidine-evoked increase in blood pressure.

Data obtained in D79N transgenic mice in the present study resembles that obtained by MacMillan et al. (1996) with brimonidine and dexmedetomidine. This data alone, therefore, suggests that α2A-adrenoceptors mediate the cardiovascular effects of rilmenidine and moxonidine. It could be argued, however, that the D79N mutation of the α2A-adrenoceptor in these mice has altered the function of putative I1-imidazoline receptors. To specifically address this point, studies were conducted in wild-type mice in which the hypotensive effect of moxonidine was evaluated after pretreatment of mice with the non-imidazoline, non-selective α2-adrenoceptor antagonist, RS-79948 (Milligan et al., 1997; Table 2), a close analogue of delequamine. Delequamine has been shown previously to be selective for α2-adrenoceptors over 5-HT receptors, specifically 5-HT1A (Brown et al., 1993). The selectivity of RS-79948 for α2-adrenoceptors over 5-HT receptors has not been determined but would not be expected to differ significantly from delequamine. This selectivity may be important since 5-HT1A receptors have been implicated in central cardiovascular regulation. Indeed, the commonly used α2-adrenoceptor antagonists yohimbine and rauwolscine have appreciable affinity for 5-HT1A receptors (Convents et al., 1989; Winter & Rabin, 1992). Interpretation of the results with RS-79948 were complicated by an effect on resting heart rate, which increased by approximately 100 beats min−1 (see Figure 4). For this reason, absolute values of heart rate were shown for experiments with RS-79948. In mice pretreated with RS-79948, moxonidine did not affect blood pressure and heart rate compared to the RS-79948/vehicle group. These data are consistent with those obtained in transgenic mice inasmuch as it suggests that the hypotensive and bradycardic effect of moxonidine is mediated by α2-adrenoceptors. Similar studies have been conducted using systemic administration of agonists and antagonists to rats (Hieble & Kolpak, 1993) and rabbits (Urban et al., 1994, 1995). The common finding in these studies was the hypotensive effect evoked by either α2-adrenoceptor (i.e. brimonidine or guanabenz) or putative I1-imidazoline receptor (i.e. clonidine, rilmenidine or moxonidine) agonists was effectively blocked by antagonists selective for α2-adrenoceptors (i.e. SK&F 86466 or yohimbine). While the affinity of RS-79948 for I1-imidazoline sites is not known, it is unlikely, based upon its structure, that it has appreciable affinity for I1-imidazoline sites. Finally, studies similar to those described above using central administration of agonists and antagonists have been conducted and have yielded less consistent results (for references see Ernsberger & Haxhiu, 1997).

In vitro studies

Given the results of in vivo studies, the agonist activity of moxonidine was evaluated at recombinant human α2-adrenoceptor subtypes. Using a [35S]-GTPγS incorporation assay, moxonidine was a selective α2A-adrenoceptor agonist with appreciable intrinsic activity (0.85) relative to the full agonist noradrenaline. Clonidine and rilmenidine have been evaluated previously in this assay (Jasper et al., 1998). Clonidine was a partial agonist at α2A-, α2B- and α2C-adrenoceptors whereas rilmenidine was inactive at all three receptor subtypes at the highest concentrations tested. The lack of efficacy of rilmenidine at the human α2A-adrenoceptor in the [35S]-GTPγS incorporation assay should be considered with caution. Clonidine produced significant hypotensive effects in wild-type mice despite possessing relatively weak efficacy in this [35S]-GTPγS incorporation assay (intrinsic activity relative to noradrenaline=0.32). The sensitivity of this assay limits quantification of intrinsic activities less than 0.20. Thus, rilmenidine may have fallen just below the level of detection. That rilmenidine was inactive at all three human α2-adrenoceptors is somewhat surprising since rilmenidine has agonist activity at the recombinant mouse α2A-adrenoceptor (Jasper et al., 1998). Moxonidine has yet to be evaluated at the recombinant mouse α2A-adrenoceptor. Possible explanations for the discrepancy between human and mouse recombinant α2-adrenoceptors include species differences, differential levels of expression and/or efficiencies of coupling or limitations of assay sensitivity.

The in vitro pharmacology of rilmenidine, moxonidine and clonidine was also assessed in the dog isolated saphenous vein, an α2A-adrenoceptor assay (MacLennan et al., 1997). All three agonists evoked concentration-dependent contractions of dog saphenous vein, with moxonidine possessing intrinsic activity equivalent to that of noradrenaline. Rilmenidine, the weakest of the three agonists in regards to intrinsic activity, possessed considerable intrinsic activity in this assay (0.70). Agonist independent affinity estimates obtained with RS-79948 suggest that the contractile activity of these agonists, under the conditions employed, was mediated by α2-adrenoceptors (specifically the α2A subtype). α2-Adrenoceptors have been reported previously to mediate, in part, the contractile effect of rilmenidine in this preparation (Marsault et al., 1996). Lastly, the relative potency of these agonists to contract dog saphenous vein and evoke hypotension in wild-type mice was essentially the same.

Conclusion

To summarize, studies in both wild-type and D79N α2A-adrenoceptor transgenic mice indicate that α2A-adrenoceptors play a critical, if not exclusive, role in mediating the hypotensive and bradycardic response to systemically-administered rilmenidine, moxonidine and clonidine. This conclusion is supported by the in vitro activity of these agonists at recombinant human α2-adrenoceptors and endogenous α2A-adrenoceptors in dog saphenous vein. Based upon these results, it seems likely that hypotension observed clinically with systemically-administered rilmenidine and moxonidine results from the activation of central α2A-adrenoceptors; a conclusion that raises an important question. Rilmenidine and moxonidine have been reported to exhibit less of the clinical adverse effects (i.e. sedation; Ernsberger et al., 1993; Yu & Frishman, 1996; Prichard et al., 1997) commonly associated with α2-adrenoceptor agonists. Recently, two independent groups have used α2-adrenoceptor transgenic mice to explore the role of α2-adrenoceptor subtypes in a multitude of physiological processes. Using D79N transgenic mice, these investigators concluded that the α2A-adrenoceptor is the primary α2-adrenoceptor subtype mediating sedation (Hunter et al., 1997; Lakhlani et al., 1997; MacMillan et al., 1998). It is difficult, therefore, to explain how rilmenidine and moxonidine could possess less clinical adverse effects than established α2-adrenoceptor agonists given the α2A-adrenoceptor activity they exhibited in the present study. Although this question has yet to be answered, it is not necessary to invoke an action at I1-imidazoline sites to explain the antihypertensive effect of these compounds.

References

- BOUSQUET P. Commentary Imidazoline receptors. Neurochem. Int. 1997;30:3–7. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(96)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOUSQUET P., FELDMAN J., BLOCH R., SCHWARTZ J. The nucleus reticularis lateralis: a region highly sensitive to clonidine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1981;69:389–392. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(81)90490-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWN C.M., MACKINNON A.C., REDFERN W.S., HICKS P.E., KILPATRICK A.T., SMALL C., RAMCHARAN M., CLAGUE R.U., CLARK R.D., MACFARLANE C.B., SPEDDING M. The pharmacology of RS-15385-197, a potent and selective α2-adrenoceptor antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;108:516–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUCCAFUSCO J.J., LAPP C.A., WESTBROOKS K.L., ERNSBERGER P. Role of Medullary I1-imidazoline and α2-adrenergic receptors in the antihypertensive responses evoked by central administration of clonidine analogs in conscious spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;273:1162–1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAN C.K.S., HEAD G.A. Relative importance of central imidazoline receptors for the antihypertensive effects of moxonidine and remenidine. J. Hyperten. 1996;14:855–864. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199607000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENG Y.-C., PRUSOFF W.H. Relationship between the inhibitor constant (Ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 percent inhibition of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONVENTS A., DE KEYSER J., DE BACKER J.-P., VAUQUELIN G. [3H]Rauwolscine labels α2-adrenoceptors and 5-HT1A receptors in human cerebral cortex. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;159:307–310. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE VOS H., BRICCA G., DE KEYSER J., DE BACKER J.-P., BOUSQUET P., VAUQUELIN G. Imidazoline receptors, non-adrenergic idazoxan binding sites and α2-adrenoceptors in the human central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1994;59:589–598. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EGLEN R.M., HUDSON A.L., KENDALL D.A., NUTT D.J., MORGAN N.G., WILSON V.G., DILLON M.P. ‘Seeing through a glass darkly': casting light on imidazoline ‘I' sites. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19:381–390. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERNSBERGER P., ELLIOTT H.L., WEIMANN H.-J., RAAP A., HAXHIU M.A., HOFFERBER E., LÖW-KRÖGER A., REID J., MEST H.-J. Moxonidine: a second-generation central antihypertensive agent. Cardiovas. Drug Rev. 1993;11:411–431. [Google Scholar]

- ERNSBERGER P., GRAVES M.E., GRAFF L.M., ZAKIEH N., NGUYEN P., COLLINS L.A., WESTBROOKS K.L., JOHNSON G.G. I1-imidazoline receptors definition, characterization, distribution, and transmembrane signaling. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1995;763:22–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb32388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERNSBERGER P., HAXHIU M.A. The I1-imidazoline-binding site is a functional receptor mediating vasodepression via the ventral medulla. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:R1572–R1579. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.5.R1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUYENET P.G. Is the hypotensive effect of clonidine and related drugs due to imidazoline binding sites. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:R1580–R1584. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.5.R1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAXHIU M.A., DRESHAJ I., EROKWU B., SCHÄFER S.G., CHRISTEN M.O., ERNSBERGER P.R. Vasodepression elicited in hypertensive rats by the selective I1-imidazoline agonist moxonidine administered into the rostral ventrolateral medulla. J. Cardiovas. Pharmacol. 1992;20:S11–S15. [Google Scholar]

- HEAD G.A., GODWIN S.J., SANNAJUST F. Differential receptors involved in the cardiovascular effects of clonidine and rilmenidine in conscious rabbits. J. Hypertension. 1993;11:S322–S323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIEBLE J.P., KOLPAK D.C. Mediation of the hypotensive action of systemic clonidine in the rat by α2-adrenoceptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;110:1635–1639. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb14012.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNTER J.C., FONTANA D.J., HEDLEY L.R., JASPER J.R., LEWIS R., LINK R.E., SECCHI R., SUTTON J., EGLEN R.M. Assessment of the role of α2-adrenoceptor subtypes in the antinociceptive, sedative and hypothermic action of dexmedetomidine in transgenic mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:1339–1344. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JASPER J.R., LESNICK J.D., CHANG L.K., YAMANISHI S.S., CHANG T.K., HSU S.A.O., DAUNT D.A., BONHAUS D.W., EGLEN R.M. Ligand efficacy and potency at recombinant α2 adrenergic receptors: agonist-mediated [35S]GTPγS binding. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998;55:1035–1043. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00631-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAKHLANI P.P., MACMILLAN L.B., GUO T.Z., MCCOOL B.A., LOVINGER D.M., MAZE M., LIMBIRD L.E. Substitution of a mutant α2a-adrenergic receptor via “hit and run” gene targeting reveals the role of this subtype in sedative, analgesic, and anesthetic-sparing responses in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997;94:9950–9955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACDONALD E., KOBILKA B.K., SCHEININ M. Gene targeting – homing in on α2-adrenoceptor-subtype function. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;118:211–219. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACLENNAN S.J., LUONG L.A., TO Z.P., JASPER J.R., EGLEN R.M. Characterization of alpha2-adrenoceptors mediating contraction of dog saphenous vein: identity with the human α2A subtype. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121:1721–1729. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACMILLAN L.B., HEIN L., SMITH M.S., PIASCIK M.T., LIMBIRD L.E. Central hypotensive effects of the α2a-adrenergic receptor subtype. Science. 1996;273:801–803. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACMILLAN L.B., LAKHLANI P.P., HEIN L., PIASCIK M., GUO T.Z., LOVINGER D., MAZE M., LIMBIRD L.E. In vivo mutation of the α2A-adrenergic receptor by homologous recombination reveals the role of this receptor subtype in multiple physiological processes. Adv. Pharmacol. 1998;42:493–496. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60796-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARSAULT R., TADDEI S., BOULANGER C.M., ILLIANO S., VANHOUTTE P.M. Rilmenidine activates postjunctional alpha1- and alpha2-adrenoceptors in the canine saphenous vein. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 1996;10:379–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1996.tb00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLIGAN C.M., LINTON C.J., PATMORE L., GILLARD N., ELLIS G.J., TOWERS P. [3H]-RS-79948-197, a high affinity radioligand selective for α2-adrenoceptor subtypes. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1997;812:176–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MINNEMAN K.P., THEROUX T.L., HOLLINGER S., HAN C., ESBENSHADE T.A. Selectivity of agonists for cloned α1-adrenergic receptor subtypes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;46:929–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRICHARD B.N.C., OWENS C.W.I., GRAHAM B.R. Pharmacology and clinical use of moxonidine, a new centrally acting sympatholytic antihypertensive agent. J. Hum. Hyperten. 1997;11:S29–S45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REIS D.J. Neurons and receptors in the rostroventrolateral medulla mediating the antihypertensive actions of drugs acting at imidazoline receptors. J. Cardiovas. Pharmacol. 1996;27:S11–S18. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199627003-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMITT H., SCHMITT H., FENARD S. Action of α-adrenergic blocking drugs on the sympathetic centres and their interactions with the central sympatho-inhibitory effect of clonidine. Arzneim-Forsch. (Drug Res.) 1973;23:40–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STORNETTA R.L., HUANGFU D., ROSIN D.L., LYNCH K.R., GUYENET P.G. Alpha-2 adrenergic receptors immunohistochemical localization and role in mediating inhibition of adrenergic RVLM presympathetic neurons by catecholamines and clonidine. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1995;763:541–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb32448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIAN W.N., DUZIC E., LANIER S.M., DETH R.C. Determinants of α2-adrenergic receptor activation of G proteins: evidence for a precoupled receptor/G protein state. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:524–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIBIRICA E., FELDMAN J., MERMET C., GONON F., BOUSQUET P. An imidazoline-specific mechanism for the hypotensive effect of clonidine: a study with yohimbine and idazoxan. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;256:606–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIMMERMANS P.B.M.W.M., SCHOOP A.M.C., KWA H.Y., VAN ZWIETEN P.A. Characterization of α-adrenoceptors participating in the cetral hypotensive and sedative effects of clonidine using yohimbine, rauwolscine and corynanthine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1981;70:7–15. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(81)90426-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- URBAN R., SZABO B., STARKE K. Is the sympathoinhibitory effect of rilmenidine mediated by alpha-2 adrenoceptors or imidazoline receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;270:572–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- URBAN R., SZABO B., STARKE K. Involvement of α2-adrenoceptors in the cardiovascular effects of moxonidine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;282:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN ZWIETEN P.A. Overview of alpha2-adrenoceptor agonists with a central action. Am. J. Cardiol. 1986;57:3E–5E. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90715-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAYSSETTES-COURCHAY C., BOUYSSET F., CORDI A.A., LAUBIE M., VERBEUREN T.J. A comparative study of the reversal by different α2-adrenoceptor antagonists of the central sympatho-inhibitory effect of clonidine. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:587–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WINTER J.C., RABIN R.A. Yohimbine as a serotonergic agent: evidence from receptor binding and drug discrimination. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;263:682–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YU A., FRISHMAN W.H. Imidazoline receptor agonist drugs: a new approach to the treatment of systemic hypertension. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1996;36:98–111. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1996.tb04174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHU Q.-M., DILLON M.P., R.M. , EGLEN, BLUE D.R., JR Effect of intravenously-administered clonidine, rilmenidine and moxonidine on blood pressure and heart rate in conscious wild-type and mutant D79N α2A-adrenoceptor (α2A–AR) mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:70P. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]