Abstract

We examined the effects of various nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitors on carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia.

First, we determined the time point at which a subcutaneous plantar injection of carrageenan into the rat hindpaw produced maximum thermal hyperalgesia. Subsequently, we demonstrated that intrathecal administration of the non-selective NOS inhibitor L-NG-nitro-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) produces a dose-dependent reduction of carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia.

Four relatively selective NOS inhibitors were then tested for their efficacy at reducing carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Initially, the effects of prolonged treatment with inhibitors of neuronal [7-nitroindazole (7-NI) and 3-bromo-7-nitroindazole (3-Br)] and inducible [aminoguanidine (AG) and 2-amino-5,6-dihydro-methylthiazine (AMT)] NOS were examined. All agents were injected three times intrathecally during the course of inflammation caused by the plantar injection of carrageenan, and thermal hyperalgesia was measured at 6 h post-carrageenan using a plantar apparatus.

All inhibitors, except for 7-NI, were effective at attenuating the carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia when compared with vehicle treatment.

Finally, the effects of early versus late administration of neuronal and inducible NOS inhibitors on carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia were examined. We found that neither 3-Br nor AG significantly affected thermal hyperalgesia when administered during the early phase of carrageenan inflammation, while only AG was able to reduce thermal hyperalgesia when administered during the late phase of the injury.

Our results suggest that inducible NOS contributes to thermal hyperalgesia in only the late stages of the carrageenan-induced inflammatory response, while neuronal NOS likely plays a role throughout the entire time course of the injury.

Keywords: Nociception, pain, thermal hyperalgesia

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) is a key mediator of nociceptive activity in numerous animal models used to study pain. Inhibiting NO production by administering a nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor diminishes nociceptive behaviours in a variety of pain models. Intrathecal (i.t.), intracerebroventricular and oral administration of the NOS inhibitor L-NG-nitro-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) prior to intraplantar formalin injection has been shown to decrease hindpaw-licking behaviour in mice (Moore et al., 1991). I.t. administration of L-NAME has also been shown to decrease thermal hyperalgesia in rats with a chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve (Meller et al., 1992). More relevant to the present study, intradermal (Nakamura et al., 1996) and intra-articular (Lawand et al., 1997) L-NAME administration has been found to reduce both mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia, respectively, due to hindpaw injection of carrageenan. Furthermore, Meller et al. (1994a) have found that i.t. administered L-NAME significantly decreases thermal hyperalgesia due to carrageenan injection while Semos & Headley (1994) have found that intravenous (i.v.) administration of L-NAME reduces carrageenan-induced mechanical hyperalgesia. Although there is considerable evidence implicating a role for NO in nociception, there is little information about which NOS isoform is primarily responsible for the alterations in nociceptive responses after a peripheral injury.

NO is not normally present in its free radical form in the mammalian body and must be synthesized in a process involving NOS (see Moore & Handy, 1997 for a review of NO metabolism). NOS exists in one of three isoforms, two constitutive isoforms that are always present within the body (neuronal and endothelial NOS) and a third isoform that is not normally present and must be synthesized de novo (inducible NOS). Neuronal NOS (nNOS) and endothelial NOS (eNOS) are primarily, but not exclusively, found within the nervous system and endothelial tissue respectively, while inducible NOS (iNOS) is commonly found in a variety of cell types including macrophages, chondrocytes and neutrophils.

Recently, investigators have begun to study the effects of selective inhibitors of the different NOS isoforms on nociceptive processing. One group (Moore et al., 1993a, 1993b) found that intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of the nNOS inhibitor, 7-nitroindazole (7-NI), significantly reduced hindpaw-licking behaviours due to formalin. Meller et al. (1994b) demonstrated that i.t. administration of the iNOS-selective inhibitor, aminoguanidine (AG), was able to inhibit thermal, but not mechanical, hyperalgesia in the zymosan inflammatory model. Relatively few studies have looked at NOS-selective inhibitors specifically in the carrageenan inflammation model. Lawand et al. (1997) found that intra-articular administration of 7-NI, 4.5 h after carrageenan-induced joint inflammation, attenuated thermal hyperalgesia for approximately 1 h. A second study by Handy & Moore (1998b) also found that 7-NI, when administered intraperitoneally (i.p.), inhibited thermal hyperalgesia due to carrageenan-induced hindpaw inflammation. This preliminary evidence suggests that NO contributes to nociception after peripheral injury; however, since these studies have used different nociceptive models and different routes of administration for the NOS inhibitors, it is difficult to establish the relative role of the different NOS isoforms in either peripheral or spinal nociceptive mechanisms.

Recent evidence also suggests that different NOS isoforms may play a role at varying points during the time course of an injury. In models of ischaemic brain injury, different isoforms of NOS have been shown to be beneficial or detrimental to an injured brain depending on the time of the NOS expression. Iadecola (1997) found that in the early stages of ischaemia, endothelial NOS is beneficial because its vasodilator effects outweigh the neurotoxic effects of neuronal NOS. However, in a later stage following ischaemia (>6 h post-injury) large amounts of iNOS are expressed and this contributes to the delayed progression of the injury. Further evidence that NO plays a time-dependent role during an injury is the finding that the iNOS inhibitor AG produces a significant reduction of hindpaw inflammation due to carrageenan when administered in the late phase (5–10 h) of the response, but not the early phase (0–4 h) (Salvemini et al., 1996). Handy & Moore (1998a) found similar results when they pretreated rats with an i.p. injection of the selective iNOS inhibitor, L-N6-iminoethyllysine (L-NIL). They demonstrated a significant reduction of inflammation when L-NIL was given in the late phase (2–6 h post-carrageenan) of the inflammatory response, but not the early phase (1–2 h post-carrageenan). Although Salvemini et al. (1996) and Handy & Moore (1998a) have demonstrated the ability of late administration of AG and L-NIL to reduce the carrageenan inflammatory response, there is little information about the temporal effects of different NOS isoforms in nociception.

The purpose of the present study was initially to first determine the effect of i.t. administration of nNOS and iNOS inhibitors (two relatively selective drugs for each of the two isoforms) on carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Once it was determined that the nNOS and iNOS inhibitors were capable of reducing carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia, one inhibitor for each NOS isoform was used to determine if the time of drug administration played a significant role in the antihyperalgesic effects of the selective NOS inhibitors. In this way we were able to determine the critical time points at which two different NOS isoforms in the spinal cord contributed to the development of the carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia.

Methods

Animals

Adult male Long Evans rats (Charles River) weighing approximately 250–275 g were used for all experiments. Animals were housed three per cage in a room with a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 08.00 and lights off at 20.00) and had free access to food and water. Ethical approval for all experiments was obtained from the animal care committee of the Clinical Research Institute of Montreal, and followed the guidelines of the Canadian Council of Animal Care.

Drugs

Drugs used in the following experiments were: carrageenan lambda, L-NG-nitro-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), D-NG-nitro-arginine methyl ester (D-NAME), 7-nitroindazole (7-NI), aminoguanidine (AG), 2-amino-5,6-dihydro-methylthiazine (AMT), [Sigma]; and 3-bromo-7-nitroindazole (3-Br) [Tocris Cookson]. All drugs were dissolved in 0.9% physiological saline except 3-Br and 7-NI which were mixed in a 30% v v−1 cremophor [Sigma] solution in saline to form a suspension.

Behavioural testing

The plantar test (Hargreaves et al., 1988) was used to measure the sensitivity to a noxious heat stimulus for the purpose of assessing thermal hyperalgesia after carrageenan inflammation of the rat hindpaw. This apparatus holds up to six rats at a time in individual, clear, Plexiglas® chambers measuring approximately 11×17×14 cm high. A radiant heat source (2.2 cm2 in diameter) is directed through the floor of the chamber onto the plantar surface of the hindpaw of each animal. A timer starts automatically when the heat source is activated and a photocell stops the timer when the rat withdraws its hindpaw. The latency is recorded (in s) when the rat has responded to the stimulus. The heat source on the plantar apparatus was set to an intensity of 30, which produced baseline latencies of approximately 15 s, and a cutoff latency of 20 s was used. For all animals, both the ipsilateral (injected) and contralateral (non-injected) hindpaws were tested twice to obtain an average response latency for each hindpaw.

Carrageenan time course

To determine the time of maximum hyperalgesia produced by carrageenan, all animals (n=6) were first tested to determine their baseline latencies to respond to the plantar test. Next, each animal received a subcutaneous (s.c.) injection of 50 μl of carrageenan (20 mg ml−1) into the plantar surface of the right hindpaw. The latency of each animal to respond to the plantar test was determined again at 2, 4, 6, 8, 24 and 48 h after the carrageenan injection.

L-NAME dose response

To determine the involvement of NO in our model of carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia, we examined the dose-dependent effects of the non-selective NOS inhibitor, L-NAME. L-NAME was administered intrathecally by acute lumbar puncture between the L5 and L6 vertebrae following the procedure of Hylden & Wilcox (1980) in doses of 30, 100, 300 and 1000 μg injection−1 in a volume of 20 μl, while the animals (n=6 per dose of L-NAME) were lightly anaesthetized for 2–3 min with 3% halothane. D-NAME (1000 μg injection−1), the inactive isomer of L-NAME, was used as a drug control treatment (n=6). To ensure that the drugs were active throughout the entire time course of the carrageenan inflammation, L-NAME and D-NAME, were administered 30 min prior to the carrageenan injection, as well as 90 and 210 min post-carrageenan. Thermal hyperalgesia testing was performed 360 min post-carrageenan at the point of maximum hyperalgesia as seen in the carrageenan time course experiment.

Effects of NOS inhibitors on carrageenan inflammation

To determine the role of nNOS and iNOS on thermal hyperalgesia produced by carrageenan injection, additional groups of rats (n=6 per drug condition including vehicle control groups) were treated with the following relatively selective inhibitors of nNOS (7-NI and 3-Br) and iNOS (AG and AMT). The doses for all NOS inhibitors were the molar equivalent to the 300 μg dose of L-NAME (i.e., 1.11 μmol), with the exception of AMT, which produced spontaneous nociceptive behaviours (e.g. caudally directed biting and scratching, occasional vocalizations) at this dose level. The dose of AMT was decreased by a factor of 10–0.11 μmol and administered to another group of rats (n=6). No spontaneous pain behaviours were observed with this dose. The baseline paw-withdrawal latencies (PWLs) of all rats were measured before administering the appropriate inhibitor; since all baselines were equivalent, comparisons between groups were based on the measurement of per cent decrease from baseline. All agents, including vehicle solutions (saline and 30% v v−1 cremophor), were administered according to the same injection schedule as L-NAME in the previous experiment and were given in a volume of 20 μl.

One relatively selective inhibitor of each isoform was again used to determine the critical time period (early versus late administration) at which it produced its antihyperalgesic effects. The effects of early and late administration of 3-Br and AG were examined in rats with carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia. For the early time period, the drugs were administered 30 min prior to and 60 min after the carrageenan injection. For the late time period, the drugs were administered at 240 min and 330 min post-carrageenan. For both time periods, animals (n=6 group−1 including vehicle control groups) were tested on the plantar apparatus at 360 min post-carrageenan.

Statistical analysis

PWLs from the noxious heat stimulus for the carrageenan time course and L-NAME dose response experiments, and per cent decrease from baseline latencies in the remaining two experiments were all analysed using ANOVA. A Dunnett test (Dunnett, 1955) was used to test for significant differences between baseline and post-carrageenan PWLs (carrageenan time course experiment) and to test for significant differences between per cent decrease from baseline latencies of vehicle and drug-treated rats (NOS inhibitor experiment). A Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test was used for multiple group comparisons between all groups in the L-NAME dose response experiment and all groups receiving nNOS and iNOS inhibitors at various time points.

Results

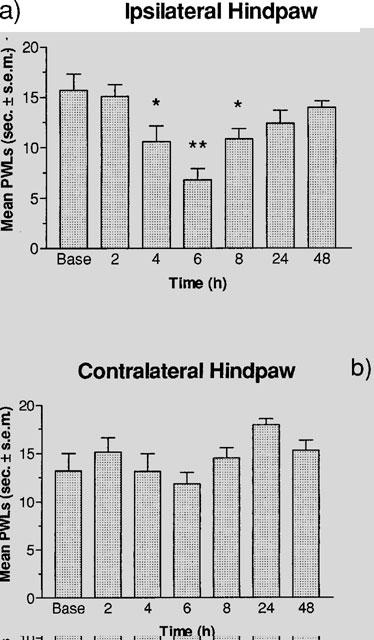

Figure 1 illustrates the time course of PWLs for the ipsilateral and contralateral hindpaws of the rats injected with carrageenan. Figure 1a demonstrates a U-shaped curve for PWLs in the ipsilateral hindpaw over the time course of carrageenan inflammation. The shortest latency to respond for the ipsilateral hindpaw occurred at 6 h post-carrageenan injection, and this was significantly lower than the baseline scores. PWLs at 4 and 8 h post-injection also showed significant decreases from baseline latencies in the ipsilateral hindpaw, while at 2, 24 and 48 h post-injection, latencies were not significantly different from baseline scores. Figure 1b shows the effect of carrageenan on PWLs in the contralateral hindpaw. No significant differences in PWLs were found between measurements and at any time post-carrageenan injection.

Figure 1.

Effect of 50 μl of carrageenan (20 mg ml−1, s.c.) on PWLs in the plantar test at 2, 4, 6, 8, 24 and 48 h post-injection. (a) A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of time (F(6,35)=6.109, P<0.001) in the ipsilateral hindpaw, and a Dunnett test revealed a significant decrease from baseline latencies at 4 and 8 h (*P<0.05) and 6 h (**P<0.01) post-carrageenan injection. (b) A one-way ANOVA (F(6,35)=2.099, P>0.05) revealed no significant effects in the contralateral hindpaw. All values are the mean latency to respond±standard error of the mean (s.e.mean) (n=6).

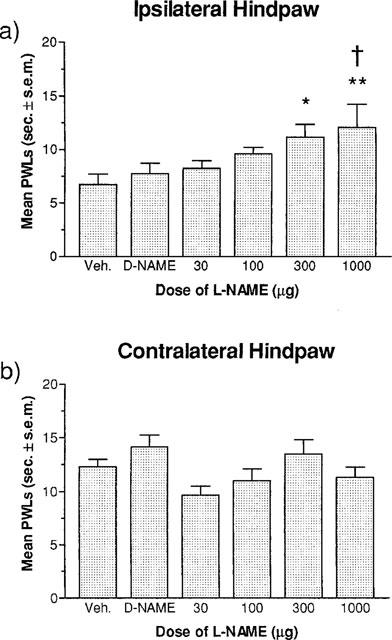

Figure 2 illustrates the dose-response for the effect of L-NAME on PWLs in the ipsilateral and contralateral hindpaws of carrageenan-treated rats. L-NAME produced a dose-dependent increase in PWLs for the ipsilateral hindpaw (Figure 2a). Significant increases in PWLs were observed for rats given L-NAME doses of 300 μg or higher compared to rats administered only the vehicle control. The highest dose of L-NAME (1000 μg injection−1) also produced PWLs significantly greater than rats receiving 1000 μg injection−1 of D-NAME. Figure 2b shows the dose-dependent effects of L-NAME on carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia in the contralateral hindpaw of the rat. No significant differences in PWLs were found between any drug condition or dose of L-NAME.

Figure 2.

Effect of increasing doses of L-NAME (30, 100, 300 and 1000 μg injection−1×3, i.t.) on carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia measured with the plantar test at 6 h post-carrageenan injection. (a) A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of dose (F5,30)=2.762, P<0.05) in the ipsilateral hindpaw. A Fisher's LSD post hoc multiple group comparison revealed significant increases in withdrawal latencies for the groups receiving three i.t. injections of 300 μg and 1000 μg of L-NAME (*P<0.05) compared to latencies in the vehicle control group, and a significant difference between the D-NAME (1000 μg×3) drug control group and the L-NAME (1000 μg×3) group (†P<0.05). (b) A one-way ANOVA (F5,30)=2.238, P>0.05) revealed no significant effects at any dose in the contralateral hindpaw. All values are the mean latency to respond±s.e.mean (n=6 per drug condition).

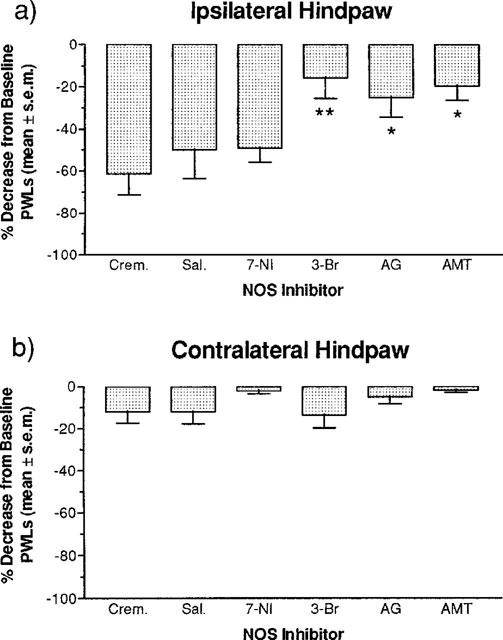

Figure 3 illustrates the effectiveness of intrathecally administered, selective NOS inhibitors on carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Ipsilateral per cent decreases from baseline PWLs for rats receiving 7-NI, 3-Br, AG and AMT are displayed in Figure 3a. 3-Br, AG and AMT produced significantly smaller per cent decreases in baseline PWLs compared to their respective vehicle control scores. However, 7-NI produced per cent decreases from baseline PWLs that were not significantly different from its vehicle control scores. Figure 3b shows the per cent decreases from baseline PWLs in contralateral hindpaw from rats receiving 7-NI, 3-Br, AG and AMT. No significant differences between any of the groups were found.

Figure 3.

Effect of NOS inhibitors 7-NI, 3-Br, AG, (1.11 μmol injection−1×3, i.t.) and AMT (0.11 μmol injection−1×3, i.t.) on per cent decreases from baseline latencies in the plantar test at 6 h post-carrageenan. (a) A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant drug effect (F5,29)=4.129, P<0.01) in the ipsilateral hindpaw and a Fisher's LSD post hoc multiple group comparison revealed that the per cent decrease from baseline latencies for the 3-Br (**P<0.01) was significantly less than the creamophor vehicle control group, and AG and AMT (*P<0.05) were significantly less than the saline vehicle control group. (b) A one-way ANOVA revealed a non-significant drug effect (F5,29)=1.622, P>0.05) in the contralateral hindpaw. All values are the mean per cent decrease from baseline latencies±s.e.mean (n=6 per drug condition).

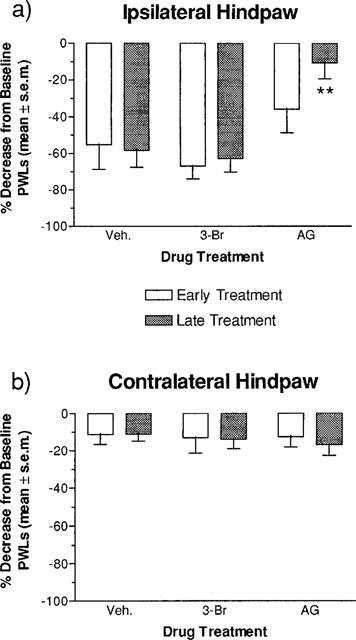

The data in Figure 4 show the effect of early and late i.t. administration of 3-Br and AG on per cent decreases from baseline PWLs in rats with carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Ipsilateral per cent decreases from baseline PWLs for rats receiving early and late treatments of 3-Br and AG are shown in Figure 4a. Early and late treatment with 3-Br and early treatment with AG produced per cent decreases from baseline PWLs that were not significantly different from vehicle control scores. However, late treatment with AG did produce per cent decreases from baseline PWLs that were significantly smaller than vehicle control scores. Figure 4b shows the contralateral per cent decreases from baseline PWLs for rats receiving early and late treatments of 3-Br and AG. No significant differences between any of the groups were found.

Figure 4.

Effect of early and late administration of the NOS inhibitors 3-Br and AG (1.11 μmol injection−1×2, i.t.) on per cent decreases from baseline latencies in the plantar test at 6 h post-carrageenan. The drug-treatment groups were compared to a vehicle control group consisting of rats treated with cremophor and saline which were not statistically different from one another (see Figure 3). (a) A one-way ANOVA of per cent decreases from baseline latencies in the ipsilateral hindpaw of rats treated in the early period revealed no significant effect of drug (F2,15)=1.911, P>0.05) after early treatment. A one-way ANOVA of per cent decreases from baseline latencies in the ipsilateral hindpaw of rats treated in the late period revealed a significant effect of drug (F2,15)=11.787, P<0.001), and a Dunnett test revealed that the AG (**P<0.01) group had a significantly lower per cent decrease from baseline latencies compared to the vehicle group. (b) Two, one-way ANOVAs revealed no significant effects of drug in the early (F2,15)=0.017, P>0.05) or late (F2,15)=0.336, P>0.05) treatments as measured in the contralateral hindpaw. All values are the mean per cent decrease from baseline latencies±s.e.mean (n=6 per drug condition).

Discussion

In the present study, we have confirmed the findings of previous studies which have shown that thermal hyperalgesia develops in the ipsilateral hindpaw of rats injected with carrageenan (Garry et al., 1994; Handy & Moore, 1998b; Hargreaves et al., 1988; Meller et al., 1994a; Semos & Headley, 1994). Similar to some of these previous findings, peak thermal hyperalgesia occurred at 6 h post-carrageenan administration, with scores returning to baseline levels by 24 h. We were also able to support the findings of Handy & Moore (1998b), Hargreaves et al. (1988) and Meller et al. (1994a) illustrating that carrageenan failed to produce thermal hyperalgesia in the contralateral hindpaw.

We also found that three i.t. injections of the non-selective NOS inhibitor, L-NAME, administered at various times during the carrageenan inflammatory response dose-dependently reduced thermal hyperalgesia in the ipsilateral hindpaw of the rat. These results add support to previous work that has found that i.t. administration of L-NAME reduces thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia in rats with two forms of peripheral neuropathies. Thus, L-NAME reduced hyperalgesia due to the ligation of the caudal sural cutaneous nerve (Salter et al., 1996) and chronic constriction of the sciatic nerve (Mao et al., 1997). More specifically, i.p. administration (Handy & Moore, 1998b), intra-articular administration (Lawand et al., 1997) as well as i.v. (Semos & Headley, 1994) and i.t. (Meller et al., 1994a) administration of L-NAME has been shown to reduce, or in some cases, completely reverse carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia. L-NAME is a non-selective inhibitor of NOS (Moore et al., 1993a,1993b; Salvemini et al., 1996) and therefore acts on all three isoforms of NOS. L-NAME's effectiveness in these various injuries may therefore be due to its actions on all three isoforms. Different kinds of injuries may involve different NOS isoforms, therefore the effects of isoform-selective inhibitors on each model of hyperalgesia should be further investigated.

We found that by inhibiting the neuronal and inducible NOS isoforms throughout the course of the inflammatory response, we were able to significantly reduce the thermal hyperalgesia due to carrageenan inflammation. All the inhibitors we tested, except for 7-NI, were able to significantly reduce carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia compared to that of the vehicle control group. The lack of effect of 7-NI in this study is inconsistent with the evidence provided by Stanfa et al. (1996) who found that i.t. administered 7-NI inhibited carrageenan-induced changes in C-fibre evoked responses in the dorsal horn neurons of rats. Our single dose of 7-NI (180 μg injection−1) was considerably greater than the dose used by Stanfa et al., 1996 (100 μg injection−1), and our total dose (540 μg) was approximately five times that of their group, so we are unable to discern the reason for our contradictory results. On the other hand, we found that the other nNOS inhibitor, 3-Br, effectively reduced carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia. 3-Br has been found to be up to four times more potent than 7-NI as an inhibitor (Bland-Ward & Moore, 1995). Thus, the present results demonstrating that 3-Br was approximately three times more effective than 7-NI in this model was not unexpected.

A number of studies have already shown that i.t. administration of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists [e.g. dextrorphan, dizocilpine maleate (MK-801), ketamine] reduce pain responses or hyperalgesia induced by peripheral injuries (e.g., formalin, chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve) (Chaplan et al., 1997; Sluka & Westlund, 1993). In particular, the NMDA receptor has been implicated in the development of hyperalgesia produced by peripheral inflammation (Laird et al., 1996; Ren et al., 1996). With respect to the present results, it should be noted that antagonists of the NMDA receptor would reduce calcium influx and this, in turn, would be expected to attenuate NO production in neurons with NMDA receptors. Thus, a role for nNOS in the development of thermal hyperalgesia would not be unexpected. Stopping the synthesis of NO by inhibiting nNOS has therefore produced a similar effect to that of NMDA antagonism, but at a point which is downstream in the process.

Our results also suggest that spinal iNOS plays a role in the development of thermal hyperalgesia associated with carrageenan inflammation. The two iNOS inhibitors that we tested reduced carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia. It has been well established that iNOS is involved in inflammation and oedema (Salvemini et al., 1996; Handy & Moore, 1998a). For example, both Salvemini's group and Handy & Moore found that inhibiting iNOS activity reduced the inflammatory response produced by hindpaw injection of carrageenan. However, only one study, to our knowledge, has examined the role of iNOS in thermal hyperalgesia associated with peripheral inflammation (Meller et al., 1994b). Our results parallel those of Meller et al. (1994b) who found that the i.t. administration of AG reduced the thermal hyperalgesia produced by intraplantar injection of zymosan.

Although it is not difficult to understand how the peripheral administration of an iNOS inhibitor would reduce peripheral inflammation (Salvemini et al., 1996), it is perhaps more difficult to explain how the i.t. administration of an iNOS inhibitor reduces thermal hyperalgesia after a peripheral injury. It is possible that a peripheral injury leads to an infiltration of macrophages in the spinal cord which, in turn, results in the release of cytokines and the production of iNOS. Such a mechanism has previously been proposed to explain the development of `secondary' hyperalgesia measured in the tailflick test following hindpaw injections of formalin (Watkins et al., 1997; Wiertelak et al., 1994). Watkins et al. (1997) demonstrated that CNI-1493, which disrupts the synthesis of cytokines, can inhibit hyperalgesia in the tail flick test due to formalin injection in the rat hindpaw. Furthermore, Wiertelak et al. (1994) determined that the non-selective NOS inhibitor, L-NAME, was able to inhibit the secondary hyperalgesia resulting from hindpaw formalin injection. This suggests that the secondary hyperalgesia due to the formalin injury may depend on cytokine-stimulated production of iNOS in the spinal cord. Our study targeted the inhibition of iNOS directly and we found a decrease in thermal hyperalgesia associated with carrageenan inflammation. This would imply that thermal hyperalgesia produced by peripheral inflammation with carrageenan may also depend on spinal iNOS induction.

It is also possible that cytokines directly released from glia may play a role in the thermal hyperalgesia associated with peripheral injury. It has been demonstrated that glia are able to release the excitatory transmitters glutamate and aspartate (Dutton, 1993) and, more importantly, it has been shown that glia can synthesize and release NO (Simmons & Murphy, 1992). Meller et al. (1994b) have shown that a peripheral injury can result in NO-dependent thermal hyperalgesia which may be mediated by the induction of iNOS in glia. These data combined with our current results on iNOS inhibition therefore provide the most direct and convincing evidence that centrally occurring NO is involved in thermal hyperalgesia due to a peripheral injury.

Finally, we have found that administering 3-Br and AG early (0–60 min) in the carrageenan response produces no effect on measures of thermal hyperalgesia. However, late (270–330 min) in the carrageenan response, we found that AG reduced carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia, while 3-Br had no effect. Salvemini et al. (1996) detected the presence of iNOS mRNA in the rat hindpaw and iNOS protein in soft tissue of the rat hindpaw at 3 and 6 h post-carrageenan administration respectively. Therefore, it would appear that to be effective, inhibitors of iNOS must be present between 4 and 6 h after tissue injury in order to be effective. Our results show that by administering the iNOS inhibitor AG spinally during this time we can reduce the thermal hyperalgesia due to carrageenan-induced paw inflammation.

In conclusion, we have found that i.t. administration of selective inhibitors of both nNOS and iNOS during the time course of carrageenan-induced paw inflammation significantly reduces thermal hyperalgesia. As for which time point each NOS isoform is most important in the development of thermal hyperalgesia, we conclude that increased induction of spinal nNOS both in the early and late period of the inflammatory response contributes to carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia. On the other hand, spinal iNOS most likely contributes to thermal hyperalgesia in the late period of the carrageenan inflammatory response.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Medical Research Council (MRC) Canada grant to TJC.

Abbreviations

- AMT

2-amino-5,6-dihydro-methylthiazine

- AG

3-bromo 7-nitroindazole (3-Br), 7-nitroindazole (7-NI), aminoguanidine

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- i.t.

intrathecal

- i.v.

intravenous

- L-NIL

L-N6-iminoethyllysine

- D-NAME

D-NG-nitro-arginine methyl ester

- L-NAME

L-NG-nitro-arginine methyl ester

- nNOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthase, NO, nitric oxide, NOS, nitric oxide synthase

- PWLs

paw-withdrawal latencies

- s.c.

subcutaneous

References

- BLAND-WARD P.A., MOORE P.K. 7-nitro indazole derivative are potent inhibitors of brain, endothelium and inducible isoforms of nitric oxide synthase. Life Sci. 1995;57:131–135. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)02046-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAPLAN S.R., MALMBERG A.B., YAKSH T.L. Efficacy of spinal NMDA receptor antagonism in formalin hyperalgesia and nerve injury evoked allodynia in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;280:829–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUNNETT C.W. A multiple comparison procedure for comparing several treatments with a control. J. Amer. Statistical Assoc. 1955;50:1096–1121. [Google Scholar]

- DUTTON G.Astrocyte amino acids: Evidence for release and possible interactions with neurons Astrocytes: Pharmacology and Function 1993San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 173–192.ed. Murphy, S. pp [Google Scholar]

- GARRY M.G., RICHARDSON J.D., HARGREAVES K.M. Carrageenan-induced inflammation alters the content of i-cGMP and i-cAMP in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Brain Res. 1994;646:135–139. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANDY R.L.C., MOORE P.K. A comparison of the effects of L-NAME, 7-NI and L-NIL on carrageenan-induced hindpaw oedema and NOS activity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998a;123:1119–1126. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANDY R.L.C., MOORE P.K. Effects of selective inhibitors of neuronal nitric oxide synthase on carrageenan-induced mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia. Neuropharmacology. 1998b;37:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARGREAVES K., DUBNER R., BROWN F., FLORES C., JORIS J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HYLDEN J.L., WILCOX G.L. Intrathecal morphine in mice: a new technique. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1980;67:313–316. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(80)90515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IADECOLA C. Bright and dark sides of nitric oxide in ischemic brain injury. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:132–139. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAIRD J.M., MASON G.S., WEBB J., HILL R.G., HARGREAVES R.J. Effects of a partial agonist and a full antagonist acting at the glycine site of the NMDA receptor on inflammation-induced mechanical hyperalgesia in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:1487–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15311.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAWAND N.B., WILLIS W.D., WESTLUND K.N. Blockade of joint inflammation and secondary hyperalgesia by L-NAME, a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor. NeuroReport. 1997;8:895–899. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199703030-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAO J., PRICE D.D., ZHU J., LU J., MAYER D.J. The inhibition of nitric oxide-activated poly(ADP-ribose). synthetase attenuates transsynaptic alteration of spinal cord dorsal horn neurons and neuropathic pain in the rat. Pain. 1997;72:355–366. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MELLER S.T., CUMMINGS C.P., TRAUB R.J., GEBHART G.F. The role of nitric oxide in the development and maintenance of the hyperalgesia produced by the intraplantar injection of carrageenan in the rat. Neuroscience. 1994a;60:367–374. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MELLER S.T., DYKSTRA C., GRZYBYCKI D., MURPHY S., GEBHART G.F. The possible role of glia in nociceptive processing and hyperalgesia in the spinal cord of the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1994b;33:1471–1478. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MELLER S.T., PECHMAN P.S., GEBHART G.F., MAVES T.J. Nitric oxide mediates the thermal hyperalgesia produced in a model of neuropathic pain in the rat. Neuroscience. 1992;50:7–10. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90377-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOORE P.K., BABBEDGE R.C., WALLACE P., GAFFEN Z.A., HART S.L. 7-Nitro indazole, an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase, exhibits anti-nociceptive activity in the mouse without increasing blood pressure. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993a;108:296–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOORE P.K., HANDY R.L.C. Selective inhibitors of neuronal nitric oxide synthase – is no NOS really good NOS for the nervous system. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18:204–211. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOORE P.K., OLUYOMI A.O., BABBEDGE R.C., WALLACE P., HART S.L. L-NG-nitro arginine methyl ester exhibits antinociceptive activity in the mouse. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;102:198–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOORE P.K., WALLACE P., GAFFEN Z., HART S.L., BABBEDGE R.C. Characterization of the novel nitric oxide synthase inhibitor 7-nitro indazole and related indazoles: antinociceptive and cardiovascular effects. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993b;110:219–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAMURA A., FUJITA M., SHIOMI H. Involvement of endogenous nitric oxide in the mechanism of bradykinin-induced peripheral hyperalgesia. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:407–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REN K., IADAROLA M.J., DUBNER R. An isobolographic analysis of the effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate and NK1 tachykinin receptor antagonists on inflammatory hyperalgesia in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:196–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALTER M., STRIJBOS P.J., NEALE S., DUFFY C., FOLLENFANT R.L., GARTHWAITE J. The nitric oxide-cyclic GMP pathway is required for nociceptive signaling at specific loci within the somatosensory pathway. Neuroscience. 1996;73:649–655. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALVEMINI D., WANG Z.-Q., WYATT P.S., BOURDON D.M., MARINO M.H., MANNING P.T., CURRIE M.H. Nitric oxide: a key mediator in the early and late phase of carrageenan-induced rat paw inflammation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:829–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEMOS M.L., HEADLEY P.M. The role of nitric oxide in spinal nociceptive reflexes in rats with neurogenic and non-neurogenic peripheral inflammation. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:1487–1497. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMMONS M. L., MURPHY S. Induction of nitric oxide synthase in glial cells. J. Neurochem. 1992;59:897–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb08328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SLUKA K.A., WESTLUND K.N. Centrally administered non-NMDA but not NMDA receptor antagonists block peripheral knee joint inflammation. Pain. 1993;55:217–225. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90150-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STANFA L.C., MISRA C., DICKENSON A.H. Amplification of spinal nociceptive transmission depends on the generation of nitric oxide in normal and carrageenan rats. Brain Res. 1996;737:92–98. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00629-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATKINS L.R., MARTIN D., ULRICH P., TRACEY K.J., MAIER S.F. Evidence for the involvement of spinal cord glia in subcutaneous formalin induced hyperalgesia in the rat. Pain. 1997;71:225–235. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)03369-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIERTELAK E.P., FURNESS L.E., HORAN R., MARTINEZ J., MAIER S.F., WATKINS L.R. Subcutaneous formalin produces centrifugal hyperalgesia at a non-injected site via the NMDA-nitric oxide cascade. Brain Res. 1994;649:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]