Abstract

The antihypertensive agent moxonidine, an imidazoline Ii-receptor agonist, also induces hypophagia and lowers body weight in the obese spontaneously hypertensive rat, but the central mediation of this action and the neuronal pathways that moxonidine may interact with are not known. We studied whether moxonidine has anti-obesity effects in the genetically-obese and insulin-resistant fa/fa Zucker rat, and whether these are mediated through inhibition of the hypothalamic neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurones.

Lean and obese Zucker rats were given moxonidine (3 mg kg−1 day−1) or saline by gavage for 21 days.

Moxonidine decreased food intake throughout by 20% in obese rats (P<0.001) and by 8% in lean rats (P<0.001), and reduced weight gain that final body weight was 15% lower in obese (P<0.001) and 7% lower in lean (P<0.01) rats than their untreated controls. Plasma insulin and leptin levels were decreased in moxonidine-treated obese rats (P<0.01 and P<0.05), but unchanged in treated lean rats. Uncoupling protein-1 gene expression in brown adipose tissue was stimulated by 40–50% (P⩽0.05) in both obese and lean animals given moxonidine. Obese animals given moxonidine showed a 37% reduction in hypothalamic NPY mRNA levels (P=0.01), together with significantly increased NPY concentrations in the paraventricular nucleus (P<0.05), but no changes in the arcuate nucleus or other nuclei; this is consistent with reduced NPY synthesis in the arcuate nucleus and blocked release of NPY in the paraventricular nucleus. In lean animals, moxonidine did not affect NPY levels or NPY mRNA.

The hypophagic, thermogenic and anti-obesity effects of moxonidine in obese Zucker rats may be partly due to inhibition of the NPY neurones, whose inappropriate overactivity may underlie obesity in this model.

Keywords: Obesity, moxonidine, insulin, leptin, neuropeptide Y, uncoupling protein, body weight, Zucker rat

Introduction

Moxonidine is an antihypertensive agent which modulates sympathetic nervous system activity and attenuates peripheral vascular resistance (Hamilton, 1994; Ernsberger et al., 1995; Ernsberger & Haxhiu, 1997). Recent studies have shown that moxonidine also markedly reduces food intake and lowers body weight in the obese spontaneously hypertensive rat (Ernsberger et al., 1996). Moreover, it improves glucose tolerance and decreases plasma insulin levels in these animals and in fructose-fed rats (Ernsberger et al., 1996; Rosen et al., 1997) and obese hypertensive patients (Lithell, 1997), implying that moxonidine may improve insulin sensitivity. Moxonidine is thought to act primarily as a selective agonist at imidazoline I1 receptors (Ziegler et al., 1996) that are mainly located in the rostro-ventrolateral medulla of the brain stem, and also in the hypothalamus (Kaan et al., 1995; Olmos et al., 1992; Garcia-Sevilla, 1997). The role of imidazoline I1 receptors in the central control of appetite and body weight is uncertain, as are the neuronal pathways and neurotransmitters that moxonidine might influence to reduce feeding.

This study focused on the possible involvement of neuropeptide Y (NPY), a potent appetite-stimulating peptide which is synthesized in arcuate nucleus (ARC) neurones that project mainly to the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and dorsomedial nucleus (DMN) (Chronwall et al., 1985; Morris, 1989). These two latter sites are important integrating centres in the control of energy homeostasis, and are closely related to the ventromedial nucleus and other sites connected with the sympathetic and parasympathetic nuclei of the brain stem (Sawchenko et al., 1985; Kaan et al., 1995). NPY injected into the PVN induces insatiable hyperphagia (Stanley et al., 1986) and decreases whole-body energy expenditure by reducing the sympathetic stimulation of thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue (Billington et al., 1994; Egawa et al., 1991); its repeated administration leads to obesity with hyperinsulinaemia and marked insulin resistance (Zarjevski et al., 1994). Certain genetically-obese, insulin-resistant rodents, notably the fa/fa Zucker rat and ob/ob and db/db mice, show evidence of increased ARC NPY neuronal activity which may be a major contributor to obesity in these models (Jeanrenaud, 1985). In particular, increased NPY release in the PVN and other sites could mediate the hyperphagia, decreased sympathetic drive to brown adipose tissue and hyperinsulinaemia, the features of the hypothalamic ‘autonomic imbalance' postulated to cause excessive weight gain (Dryden et al., 1994).

Since moxonidine given to the obese spontaneously hypertensive rat induced hypophagia and weight loss (Ernsberger et al., 1996), thus opposing the central actions of NPY, we postulated that it acts to inhibit the NPY neurones of the ARC. The main aim of this study was to determine whether moxonidine also exerts anti-obesity effects in obese Zucker rats, and whether these are mediated by inhibition of ARC NPY neurones. We assessed NPY neuronal activity by measuring hypothalamic NPY mRNA and regional hypothalamic NPY concentrations. Secondly, as the effects of moxonidine on thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue and energy expenditure are unknown, we also investigated uncoupling protein-1 (UCP-1) gene expression in brown adipose tissue as an index of this tissue's thermogenic activity. Finally, we explored the possible roles of circulating leptin, insulin and corticosterone in the moxonidine-induced changes in energy balance. Leptin and insulin inhibit, whereas corticosterone stimulates, the ARC NPY neurones. Leptin is of particular interest as the NPY neurones express the fully functional OB-Rb leptin receptor (Mercer et al., 1996) and are thought to be disinhibited by the fa mutation, which lies in the extracellular domain of the leptin receptor (Chua et al., 1996), thus causing the neurones' inappropriate overactivity which contributes to obesity (Dryden et al., 1994).

Methods

Animals

Male Zucker lean (Fa/?) and obese (fa/fa) rats aged 9 weeks (Charles River Ltd, Margate, Kent, U.K.) were housed singly in wire-bottomed cages in a room maintained at 22°C, with a 12 h light : dark cycle (lights on at 08 : 00 h). Rats were fed standard laboratory chow (CRM, Biosure, Cambridge, U.K.) and water ad libitum, except in the pair-fed, untreated obese group identified below. Food intake, body weight and general condition were recorded daily for each animal.

Treatment procedures

In each study, moxonidine (Solvay, Hannover, Germany) dissolved in 1 ml saline (0.9% NaCl, pH 5.5) was given by gavage at a dose of 3 mg kg−1 day−1 at 09 : 00 h each day for 21 days. Lean and obese controls similarly received an equal volume of saline.

Study 1 compared the effects of moxonidine in freely-fed obese and lean rats with matched saline-treated controls; each group comprised eight animals. Hypothalamic NPY mRNA was measured in this study, together with blood analytes, UCP-1 mRNA in brown adipose tissue and ob mRNA in white fat.

As moxonidine was found to decrease food intake, Study 2 was undertaken in obese rats, and included a pair-fed group to exclude the effects of underfeeding per se on central and peripheral peptides. One group of obese rats (n=8) received similar dose of moxonidine as used in Study 1 for 21 days, while freely-fed obese controls (n=8) received saline. A group of untreated obese rats (n=8) was pair-fed to match the food intake of the moxonidine-treated rats during the previous day. NPY concentrations in individual hypothalamic nuclei were measured in these animals, and UCP-1 mRNA levels in brown fat was also studied.

At the end of the study, rats were sacrificed by carbon dioxide inhalation and exsanguinated immediately by cardiac puncture. Blood glucose was measured using an Exactech electrochemical meter (Medisense, Abingdon, Oxon, U.K.), and plasma was stored at −40°C for subsequent measurement of leptin, insulin and corticosterone concentrations. Brown adipose tissue was rapidly excised from the interscapular fat pad, and the epididymal white adipose tissue was dissected and weighed; both were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until measurement of UCP-1 mRNA and ob mRNA, respectively.

Hypothalamic microdissection

For NPY mRNA measurements, a hypothalamic block was dissected from a slice of brain tissue cut between the optic chiasm and the mammillary bodies, using a horizontal cut immediately below the anterior commissure and vertical cuts through the edge of the septum and perihypothalamic sulcus. The blocks were snap-frozen and stored at −70°C until extraction of RNA.

For measurement of regional hypothalamic NPY concentrations, a coronal brain slice including the hypothalamus was cut into six 500-μm frontal slices using a vibrating microtome (Williams et al., 1989). The following three hypothalamic areas were microdissected using a fine blade or a blunt 18-gauge needle: PVN, DMN and the ARC (including the median eminence). Pooled tissue from each area in each rat was boiled in 400 μl of 0.1 M HCl for 10 min, sonicated for 30 s and the extracts were frozen at −40°C until assayed for NPY and protein concentrations.

Assays

Regional hypothalamic NPY concentrations were measured using an in-house radioimmunoassay (RIA) which employed 125I-labelled porcine NPY (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, U.K.) and porcine NPY as standard (Bachem Inc, Essex, U.K.). NPY antiserum (116-6#) raised in our laboratory in a rabbit against porcine NPY, was used in a final dilution of 1 : 90,000. Cross-reactivity with peptide YY and related peptides was <1%. The sensitivity of the assay was 2 fmol/tube, with an intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) <4.0%. Samples were measured in duplicate in a single assay. Protein concentrations in hypothalamic extracts were determined by a modified Lowry method and NPY levels in each region were expressed as fmol/μg protein.

Plasma leptin levels were determined using an RIA kit from Linco Research (Biogenesis, Poole, Dorset, U.K.), with an intra-assay CV of 3%. Plasma insulin and corticosterone levels were measured using RIA kits (Pharmacia Diagnostic, Cambridge, U.K. and DPC, Caernarvon, U.K.); each had a within-assay CV of 4%.

Measurements of NPY mRNA

Total hypothalamic RNA was isolated from hypothalamic tissue blocks using the guanidinium thiocyanate phenol-chloroform method (Jones et al., 1992) and RNA concentration determined from the absorbance at 260 nm. Twenty micrograms of total RNA per sample was applied to a 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel and separated by electrophoresis. The RNA was transferred overnight to a charged membrane (Boehringer-Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) by capillary blotting and then cross-linked under UV light.

Pre-hybridization was performed at 42°C for 1 h in a buffer containing 50% formamide, 5×standard saline citrate (SSC), 2% blocking reagent (Boehringer Mannheim), 0.1% N-lauroylsarcosine, 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) and 7% sodium dodecyl sulphate. Hybridization was at 42°C overnight in the pre-hybridization solution with a 42-mer oligonucleotide (R&D Systems, Oxon, U.K.) which was end-labelled (3′ and 5′) with digoxigenin at a concentration of 25 ng ml−1. Post-hybridization washes were performed as described previously (Trayhurn & Duncan, 1994). The membrane was incubated with an antibody against digoxigenin (Fab fragment; Boehringer), which was conjugated to alkaline phosphatase, for 30 min at room temperature. The membrane was then sprayed with 0.25 mM chemiluminescence substrate CDP-star (Tropix, Massachusetts, U.S.A.). Signals were obtained by exposure of the membrane to X-ray film for 30 min at room temperature, and the 0.9 kb band corresponding to NPY mRNA was quantified using image-scan densitometry (AIS System, Imaging Technology, Brock University, St Catherines, Ontario, Canada).

To check the loading and transfer of RNA during blotting, the blot was stripped and re-probed for 18S rRNA with a 31-mer digoxigenin-labelled antisense oligonucleotide at a concentration of 10 pg ml−1, as previously described (Trayhurn et al., 1995). The amount of NPY mRNA was expressed as the NPY mRNA/18S rRNA ratio.

Measurements of UCP-1 mRNA and ob mRNA

Following extraction of RNA from brown or white adipose tissue, UCP-1 mRNA and ob mRNA were each detected by Northern blotting in conjunction with the chemiluminescence method described above. UCP-1 mRNA measurements employed a digoxigenin-labelled 32-mer antisense oligonucleotide (Trayhurn & Duncan, 1994), and ob mRNA a 33-mer antisense oligonucleotide (Trayhurn et al., 1995). 18S rRNA levels were similarly determined as a reference for both UCP-1 mRNA and ob gene, and mRNA levels were expressed as the ratio of UCP-1/18S or ob/18S signals.

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as mean±s.e.mean. Blood analytes, NPY mRNA, UCP-1 mRNA and ob mRNA levels were compared between groups using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). For food intake, body weight and NPY concentrations in individual hypothalamic regions, repeated-measure two-way ANOVA coupled to a post-hoc modified t-test was performed to determine whether there were significant differences between groups. Group differences in NPY levels within individual nuclei were then further examined by Student's unpaired t-test. A P value of 0.05 or less at two-tail level was taken as significant.

Results

Food intake and body weight changes

Study 1

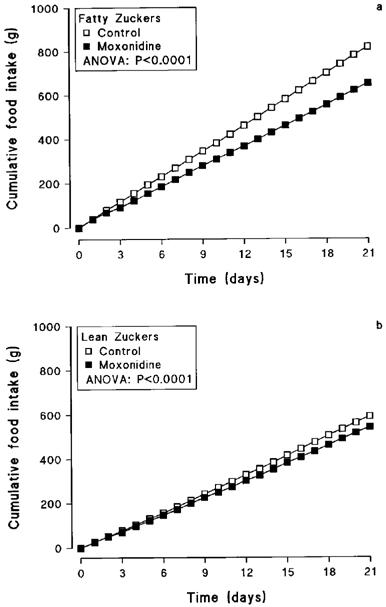

Basal food intake was 52% higher in untreated obese Zucker rats than in lean controls (39.9±1.0 vs 26.2±1.0 g day−1). Moxonidine treatment for 21 days significantly reduced food intake and body weight in both obese and lean rats (Table 1), the effects being more marked in the obese group. Obese animals given moxonidine showed a rapid-onset (from day 2) 20% suppression of food intake compared with the saline-treated controls, that lasted throughout the experimental period (ANOVA: F1,20=714.65; P<0.0001) (Table 1 and Figure 1a). Lean rats treated with moxonidine also ate less than the controls from day 3, with a less marked 8% reduction in total food intake (ANOVA: F1,20=155.49; P<0.0001) (Table 1 and Figure 1b).

Table 1.

Metabolic data, plasma hormones, ob gene and NPY mRNA levels for lean and obese Zucker rats (Study 1)

Figure 1.

Cumulative food intake in obese (a) and lean (b) Zucker rats treated orally with moxonidine (3 mg kg−1) or saline for 21 days. Shown are lean controls (n=8), lean treated with moxonidine (n=8), obese controls (n=8) and obese treated with moxonidine (n=8).

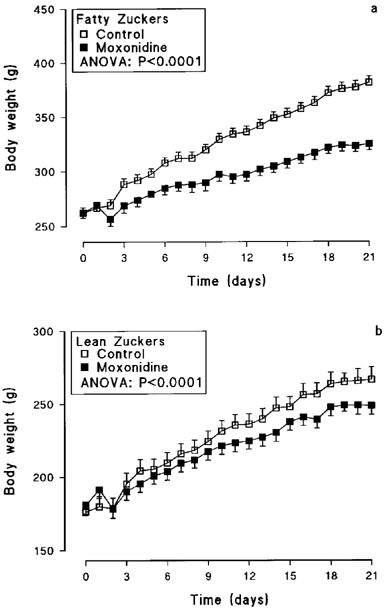

Moxonidine caused a progressive and significant decline in weight gain from day 2 in obese rats (ANOVA: F 1,20=344.56; P<0.0001), with their final body weight being 15% lower (P<0.001) than controls (Table 1 and Figure 2a). Lesser decreases in weight gain were also seen in treated lean rats (ANOVA: F1,20=21.17; P<0.0001), with final body weight being 7% below lean controls (Table 1 and Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Body weight of obese (a) and lean (b) Zucker rats treated orally with moxonidine (3 mg kg−1) or saline for 21 days (n=8 per group; means±s.e.mean).

Gonadal fat mass was 4.6 fold higher in untreated obese rats than in lean controls (P<0.0001). Moxonidine treatment led to a significant reduction in fat mass of 20% (P=0.02) in obese and 14% (P=0.03) in lean animals (Table 1).

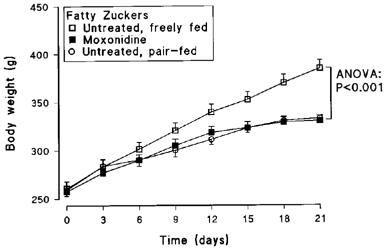

Study 2

Moxonidine treatment of fatty Zucker rats had similar effects on food intake (19% reduction) and body weight (22% decrease in final weight) as in Study 1. Body weight in the untreated, pair-fed group tracked closely with that in the untreated group (Figure 3), and there was no significant difference in final body weight between these two groups (P>0.05). There was, however, a striking difference in behaviour between these groups, the moxonidine-treated animals remaining placid while the untreated, pair-fed group displayed intense food-seeking activity and restlessness.

Figure 3.

Body weight of obese Zucker rats treated orally with moxonidine (3 mg kg−1) or saline, and untreated pair-fed for 21 days (n=8 per group; means±s.e.mean).

Plasma hormone and glucose concentrations

Study 1

Plasma leptin levels were 9 fold higher (P<0.01) in untreated obese than in lean animals (Table 1). Moxonidine caused a 14% fall in leptin levels in obese (P<0.05) but not in lean rats (Table 1). Leptin levels were positively correlated with gonadal fat mass weight in both lean (r=0.492, P<0.05) and obese (r=0.739, P<0.01) groups. The y-axis intercepts showed a highly significant difference (P<0.001), while there was no significant difference (P>0.05) between the slopes of the correlations in fatty and lean groups (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Plasma leptin levels plotted against weight of gonadal fat in lean (r=0.492, P<0.05) and obese (r=0.739, P<0.01) rats, respectively.

Untreated obese rats displayed plasma insulin levels that were over 6 fold higher than the lean controls (P<0.001). Moxonidine treatment lowered insulin levels by 46% (P<0.001) in obese rats, but these were unaffected in lean rats (Table 1). There was a positive correlation between plasma leptin levels and insulin levels in both lean (r=0.49, P=0.05) and obese (r=0.49, P<0.05) rats.

Plasma corticosterone levels were significantly higher in untreated obese rats than in lean controls (P<0.01), but moxonidine treatment had no significant effect on corticosterone in either lean or obese rats (Table 1).

Circulating glucose concentrations did not differ between groups (Table 1).

Study 2

Similar to Study 1 moxonidine-treated obese rats showed a 47% decrease (P<0.001) in plasma insulin levels (Table 2). Plasma insulin was also markedly reduced by 76% in untreated pair-fed animals compared with untreated freely-fed animals (P<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Metabolic data, plasma insulin, UCP-1 mRNA levels for obese Zucker rats (Study 2)

obmRNA

ob mRNA levels were 6 fold higher in obese rats than in lean controls (P<0.001; Table 1). There were no significant changes in ob gene expression in moxonidine-treated lean and obese rats.

UCP-1 mRNA

Study 1

Figure 5 shows a representative Northern blot and levels of UCP-1 mRNA and 18S rRNA in brown adipose tissue from Study 1. Untreated obese rats (n=8) displayed a marked reduction in UCP-1 mRNA levels relative to lean controls (n=8; P<0.01). Moxonidine treatment doubled UCP-1 mRNA levels in both lean (n=8; P<0.05) and obese (n=8; P=0.05) animals, compared with their corresponding controls.

Figure 5.

The upper panel shows a representative autoradiogram of the Northern blots for UCP-1 mRNA in brown adipose tissue from lean and obese Zucker rats treated with moxonidine (3 mg kg−1) or saline for 21 days. The lower panel shows the relative densitometric values for UCP-1 mRNA. Bars are mean±s.e.mean for eight rats. *P⩽0.05 vs corresponding controls; ††P<0.01 vs lean controls.

Study 2

In Study 2, UCP-1 mRNA levels in moxonidine-treated obese rats (n=8) were again significantly increased above freely-fed obese controls (n=8; P<0.05). By contrast, the pair-fed untreated obese group (n=8) showed a marked reduction in UCP-1 mRNA levels compared with freely-fed obese controls (P<0.05) (Table 2).

Hypothalamic NPY and NPY mRNA levels

In agreement with earlier studies, hypothalamic NPY mRNA levels (Study 1) were significantly higher by 37% in obese rats than in lean rats (P<0.05) (Table 1). Moxonidine treatment caused a 37% fall in NPY mRNA (P=0.01) in obese rats. In lean rats, there were no significant changes in NPY mRNA levels with moxonidine treatment (Table 1).

NPY concentrations in the three hypothalamic regions in obese rats treated with moxonidine (n=8) or saline (n=8), or pair-fed (n=8) for 21 days in Study 2 are shown in Figure 6. Two-way ANOVA revealed significant effects attributable to group (F2,62=3.56; P=0.03) and to hypothalamic region (F2,62=12.63; P<0.001). With moxonidine treatment, NPY concentrations were significantly increased by 51% (P<0.05) in the PVN. There were no significant changes in NPY concentrations in the ARC (the intrahypothalamic site of synthesis) or DMN. Pair-feeding had no effect on NPY concentrations when compared with freely-fed controls or the moxonidine-treated group.

Figure 6.

Neuropeptide Y concentrations in three hypothalamic regions in obese rats treated with moxonidine (3 mg kg−1) or saline for 21 days, and in untreated pair-fed obese rats. Values are mean±s.e.mean, n=eight per group. *P<0.05 vs controls. Key to regions: PVN, paraventricular nucleus; DMN, dorsomedial nucleus; ARC, arcuate nucleus with median eminence.

Discussion

Recent data have shown that the selective imidazoline I1-receptor agonist moxonidine not only possesses potent antihypertensive properties, but also improve insulin sensitivity, a key abnormality of the metabolic ‘syndrome X' (Krentz & Evans, 1998). However, its effects on obesity, another central feature of syndrome X, have been little studied. A previous report by Ernsberger and colleagues (1996) indicated that moxonidine induces hypophagia and weight loss in the obese spontaneously hypertensive rat, but the central mediation of this action and the possible contribution of increased thermogenesis to weight loss, are not known. NPY is a powerful inducer of feeding and fat accumulation, and overactivity of the ARC NPY neurones is suggested to be an important contributor to obesity in the fa/fa Zucker rat (Dryden et al., 1994). Our study therefore aimed to investigate whether moxonidine also has anti-obesity effects in this model, and whether these are mediated through inhibition of the hypothalamic NPY neurones.

We used an oral dose of moxonidine (3 mg kg−1 day−1) which has been shown to cause only a slight lowering of blood pressure in spontaneous hypertensive rats. When given for 21 days, it caused sustained reductions in both food intake and weight gain in fa/fa Zucker rats, which agrees with the previous report using a higher dose (8 mg kg−1 day−1) of the drug in obese spontaneously hypertensive rat (Ernsberger et al., 1996). Plasma insulin was elevated in untreated obese rats, insulinaemia fell markedly while the glucose/insulin ratio rose significantly after moxonidine administration, suggesting that moxonidine improves the severe insulin resistance in this mutant. Lean rats treated with moxonidine also ate less and weighed progressively less than controls, but these changes were much less marked than in obese animals. Weight loss apparently reflected depletion of body fat stores, as evidenced by the significant falls in gonadal fat mass in both obese and lean animals. Our data, together with Ernsberger's (Ernsberger et al., 1996), suggest that the ability of moxonidine to lower weight is accentuated in animals that are obese and insulin-resistant.

Moxonidine-induced hypophagia and weight loss were associated with changes in hypothalamic NPY that are consistent with inhibition of the ARC NYP neurones at various levels. In obese rats given moxonidine, NPY levels were increased in the PVN, a major site of NPY release, but not in the ARC, where NPY is synthesized; concomitantly, moxonidine reduced the hypothalamic expression of NPY mRNA. We suggest that this combination of changes indicates inhibition of the ARC NPY neurones, and that the increased NPY levels in the PVN are due to blockade of NPY release causing its local accumulation in the PVN terminals; this will need to be confirmed by direct measurements of NPY secretion in the PVN in vitro (Dryden et al., 1995). It has been reported previously that the obese Zucker rat shows a typical weight loss when underfed and, unlike lean rats, does not display increases in NPY mRNA or in NPY levels in the hypothalamic regions (Sanacora et al., 1990; McKibbin et al., 1991; Dryden et al., 1996). Our findings are consistent with theirs. The links between the I1 receptors, thought to reside mainly in the ventrolateral medulla, and the ARC NPY neurones are not known. Interaction may be mediated by the neural pathways that connect the hypothalamus and various brainstem regions, or through an indirect action, such as improving insulin sensitivity within the central nervous system. Insulin suppresses feeding and inhibits the NPY neurones when intracerebroventricularly injected, but obese Zucker rats are insensitive to this central effect of insulin. If moxonidine improved insulin action centrally as well as peripherally, it would be predicted to inhibit the ARC NPY neurones, and decrease feeding and stimulate thermogenic activity in brown adipose tissue.

We have also shown that moxonidine significantly increases UCP-1 mRNA, despite the presence of weight loss which normally reduces brown fat thermogenic activity (Trayhurn, 1993); a fall in UCP-1 mRNA was confirmed in the pair-fed obese rats. This unexpected observation suggests that moxonidine might increase energy expenditure via centrally inhibiting NPY neurons. The central regulation of the sympathetic outflow to brown adipose tissue involves several hypothalamic regions including the medial preoptic area, ventromedial nucleus and PVN (Freeman & Wellman, 1987; Holt et al., 1987), and administration of NPY intracerebroventricularly or into the PVN suppresses sympathetic afferent to brown adipose tissue (Egawa et al., 1991) and reduces UCP-1 mRNA (Billington et al., 1994). The NPY neurones are therefore suggested to be an important influence, tonically inhibiting brown fat thermogenesis and so restraining energy expenditure (Bing et al., 1997). It is possible that moxonidine-induced increases in UCP-1 mRNA in obese rats might result from its central inhibitory action on NPY neurones which in turn activates sympathetic mediated thermogenic activity in brown adipose tissue.

Interestingly, insulin resistance itself may contribute to impaired thermogenesis in obese mutant rodents (Geloen & Trayhurn, 1990), as ob/ob mice fail to activate brown adipose tissue in response to acute cold exposure (Mercer & Trayhurn, 1984), while this defect is corrected when insulin sensitivity is restored by treatment with the thiazolidinedione, ciglitazone (Mercer & Trayhurn, 1986). Moxonidine's ability to improve insulin resistance, confirmed in our study, might therefore contribute. It is not clear how this effect might interact with central actions of the drug on the NPY neurones.

The closeness of the body weight curves in the moxonidine-treated, and untreated, pair-fed obese groups is interesting, and at first sight suggests that the suppression of food intake is sufficient to explain weight loss, and that any effects of moxonidine on brown adipose tissue are irrelevant; UCP-1 gene expression was stimulated by moxonidine but suppressed by food restriction. However, the pair-fed (food-restricted) rats were physically very active, spending most of their time in food-seeking and other exploratory behaviours. We have found increased motor activity to be a consistent feature of long-term food restriction at this degree. It therefore seems that the enhanced thermogenesis with moxonidine was comparable to the extra energy expended through this increased physical activity induced by hunger.

We investigated the possible involvement of leptin, insulin and corticosterone, hormones which are implicated in the regulation of energy balance. Insulin and leptin both inhibit appetite and activate brown fat thermogenesis (Campfield et al., 1995; Pelleymounter et al., 1995), and both hormones apparently inhibit the NPY neurones (Schwartz et al., 1992; 1996; Hokansson et al., 1996; Mercer et al., 1996). However, the fall of both hormones in this study argues against their involvement in mediating moxonidine-induced hypophagia. Insulin and leptin secretion are both inhibited by sympathomimetic agents and theoretically moxonidine could act partly by selectively increasing the sympathetic activity to white adipose tissue and the pancreatic β-cells, as appears to be the case with brown adipose tissue (Carpene et al., 1997; Morgan et al., 1995). Insulin levels may also fall in parallel with the improvement in insulin sensitivity. The suppression of plasma leptin by moxonidine was proportional in both lean and obese groups to the reduced fat mass, consistent with its correlation with body fat mass in rodents and humans (Maffei et al., 1995; Considine et al., 1996; Solin et al., 1997). The markedly higher levels of leptin in fatty Zucker rats, whether treated or untreated, are probably the consequence of the breakdown of leptin signalling through the fa mutation, analogous to the hyperinsulinaemia that accompanies insulin-receptor mutations. Glucocorticoids stimulate feeding and may act to suppress thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue, possibly by directly stimulating the ARC NPY neurones (Strack et al., 1995), but corticosterone levels were unaffected by moxonidine.

In conclusion, we have shown moxonidine induces hypophagia and slows weight gain in obese and lean Zucker rats. These changes were more pronounced in obese rats, in which there was evidence of significantly enhanced insulin sensitivity, and appear to be mediated by an inhibitory effect of moxonidine on hypothalamic NPY neurones in the ARC in obese animals. Should this effect extend to other obese states such as diet-related obesity, moxonidine might show a promise for the treatment of syndrome X.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Solvay Pharmaceuticals. We would like to thank the staff of the Biomedical Service, Liverpool University for their conscientious care of the animals.

Abbreviations

- ARC

arcuate nucleus with median eminence

- DMN

dorsomedial nucleus

- NPY

neuropeptide Y

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus

- UCP-1

uncoupling protein-1

References

- BILLINGTON C.J., BRIGGS J.E., GRACE H.M., LEVINE A.S. Neuropeptide Y in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus: a center coordinating energy metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:R1765–R1770. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.6.R1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BING C., PICKAVANCE L., WANG Q., FRANKISH H.M., TRAYHURN P., WILLIAMS G. Role of hypothalamic neuropeptide Y neurones in the defective thermogenic response to acute cold exposure in fatty Zucker rats. Neuroscience. 1997;80:277–284. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMPFIELD L.A., SMITH F.J., GUISEZ Y., DEVOS R., BURN P. Recombinant mouse OB protein: evidence for a signal linking adiposity and central neuronal networks. Science. 1995;269:546–549. doi: 10.1126/science.7624778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARPENE C., MARTI L., MORIN N.N., PREVOT D., FONTANA E., LAFONTAN M. Imidazoline-I2 binding sites in adipose tissue: relationship with amine oxidase activity and glucose metabolism. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122 Suppl:183p. [Google Scholar]

- CHRONWALL B.M., DIMAGGIO D.A, MASSARI V.J., PICKEL V.M., RUGGIERO D.A., O'DONOHUE T.L. The anatomy of neuropeptide Y containing neurones in the rat brain. J. Neurosci. 1985;15:1159–1181. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHUA S.C., CHUNG W.K., WU-PENG X.S., ZHANG Y., LIU S.M., TARTAGLIA L., LEIBEL R.L. Phenotypes of mouse diabetes and rat fatty due to mutations in the OB (leptin) receptor. Science. 1996;271:994–996. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONSIDINE R.V., SINHA M.K., HEIMAN M.L., KRIAUCIUNAS A., STEPHENS T.W., NYCE M.R., OHANNESIAN J.P., MARCO C.C., MCKEE L.J., BAUER T.L., CARO J.F. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. New. Eng. J. Med. 1996;334:292–295. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602013340503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRYDEN S., FRANKISH H.M., WANG Q., PICKAVANCE L., WILLIAMS G. The serotonergic agent fluoxetine reduces neuropeptide Y levels and neuropeptide Y secretion in the hypothalamus of lean and obese rats. Neuroscience. 1996;72:557–566. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00566-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRYDEN S., FRANKISH H.M., WANG Q., WILLIAMS G. Neuropeptide Y and energy balance: one way ahead for the treatment of obesity. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 1994;246:293–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1994.tb01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRYDEN S., PICKAVANCE L., FRANKISH H.M., WILLIAMS G. Increased neuropeptide Y secretion in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of obese (fa/fa) Zucker rats. Brain Res. 1995;690:185–188. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00628-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EGAWA M., YOSHIMATSU H., BRAY G.A. Neuropeptide Y suppresses sympathetic activity to intrascapular brown adipose tissue in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;260:R328–R334. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.2.R328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERNSBERGER P., GRAVES M.E., GRAFF L.M., ZAKIEH N., NGUYEN P., COLLINS L.A. I1-imidazoline receptors. Definition, characterization, distribution, and transmembrane signaling. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1995;763:22–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb32388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERNSBERGER P., HAXHIU M.A. The I1-imidazoline-binding site is a functional receptor mediating vasodepression via the ventral medulla. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:R1572–R1579. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.5.R1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERNSBERGER P., KOLETSKY R.J., COLLINS L.A., BEDOL D. Sympathetic nervous system in salt-sensitive and obese hypertension: Amelioration of multiple abnormalities by a central sympathetic agent. Cardiovasc. Drugs. Ther. 1996;10:275–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00120497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREEMAN P.H., WELLMAN P. Brown adipose tissue thermogenesis induced by low level electrical stimulation of hypothalamus in rats. Brain. Res. Bull. 1987;18:7–11. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(87)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCIA-SEVILLA J.A. Imidazoline receptors in human brain. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122 Suppl:182p. [Google Scholar]

- GELOEN A., TRAYHURN P. Regulation of the level of uncoupling protein in brown adipose tissue by insulin. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;258:R418–R424. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.258.2.R418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMILTON C.A.Chemistry, mode of action and experimental pharmacology of moxonidine The I1-imidazoline receptor agonist moxonidine: a new antihypertensive 1994London: Royal Society of Medicine; 1–23.ed. Van Zwieten, P.A., Hamilton, C.A. & Prichard, B.V.C. pp [Google Scholar]

- HOKANSSON M.L., HULTING A.L., MEISTER B. Expression of leptin receptor mRNA in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus-relationship with NPY neurons. Neuroendocrinology. 1996;7:3087–3092. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199611250-00059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLT S.J., WHEAL H.V., YORK D.A. Hypothalamic control of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis in Zucker lean and obese rats: Effects of electrical stimulation of the ventromedial nucleus and other hypothalamic centres. Brain Res. 1987;405:227–233. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JEANRENAUD B. A hypothesis on the aetiology of obesity: dysfunction of the central nervous system as a primary cause. Diabetologia. 1985;28:502–513. doi: 10.1007/BF00281984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES P.M., PIERSON A.M., WILLIAMS G., GHATEI M.A., BLOOM S.R. Increased hypothalamic neuropeptide Y messenger RNA in two rat models of diabetes. Diabetic. Med. 1992;9:76–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1992.tb01719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAAN E.C., BRUCKNER R., FROHLY P., TULP M., SHAFER S.G., ZIEGLER D. Effects of agmatine and moxonidine on glucose metabolism: an integrated approach towards pathophysiological mechanisms in cardiovascular metabolic disorders. Cardiovasc. Risk. Factors. 1995;5 Suppl 1:19–27. [Google Scholar]

- KRENTZ A.J., EVANS A.J. Selective imidazoline receptor agonists for metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 1998;351:152–153. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)22003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LITHELL H.O. Considerations in the treatment of insulin resistance and related disorders with a new sympatholytic agent. J. Hypertens. 1997;15 Suppl 1:S39–S42. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715011-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAFFEI M., HALAAS J.L., RAVUSSIN E., PRATLEY R.W., LEE G.H., ZHANG Y., FEI H., KIM S., LALLONE R., RANGA-NATHAN S., KERN N., FRIEDMAN J.M. Leptin levels in human and rodent: measurement of plasma leptin and ob RNA in obese and weight reduced subjects. Nature Med. 1995;1:1155–1161. doi: 10.1038/nm1195-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCKIBBIN P.E., COTTON S.J., MCMILLAN S., HOLLOWAY B., MAYERS R., MCCARTHY H.D., WILLIAMS G. Altered neuropeptide Y concentrations in specific hypothalamic regions of obese (fa/fa) Zucker rats. Diabetes. 1991;40:1423–1429. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.11.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERCER J.G., HOGGARD N., WILLIAMS L.M., LAWRENCE C.B., HANNAH L.T., MORGAN P.J., TRAYHURN P. Coexpression of leptin receptor and preproneuropeptide Y mRNA in arcuate nucleus of mouse hypothalamus. J. Neuroendocrinol. 1996;8:530–532. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1996.05161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERCER S.W., TRAYHURN P. The development of insulin resistance in brown adipose tissue may impair the acute cold-induced activation of thermogenesis in genetically obese (ob/ob) mice. Biosci. Rep. 1984;4:933–940. doi: 10.1007/BF01116891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERCER S.W., TRAYHURN P. Effects of ciglitazone on insulin resistance and thermogenic responsiveness to acute cold in brown adipose tissue of genetically obese (ob/ob) mice. FEBS Lett. 1986;195:12–16. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORGAN N.G., CHAN S.L.F., BROWN C.A., TSOLI E. Characterization of the imidazoline binding site involved in regulation of insulin secretion. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1995;763:361–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb32424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORRIS B.J. Neuronal localisation of neuropeptide Y gene expression in rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 1989;290:358–368. doi: 10.1002/cne.902900305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLMOS G., MIRALLES A., BARTUREN F., GARCIA-SEVILLA J.A. Characterization of brain imidazoline receptors in normotensive and hypertensive rats: differential regulation by chronic imidazoline drug treatment. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;260:1000–1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PELLEYMOUNTER M.A., CULLEN M.J., BAKER M.B., HECHT R., WINTERS D., BOONE T., COLLINS F. Effects of the obese gene product on body weight regulation in ob/ob mice. Science. 1995;269:540–543. doi: 10.1126/science.7624776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSEN P., OHLY P., GLEICHMAN H. Experimental benefit of moxonidine on glucose metabolism and indulin secretion in the fructose-fed rat. J. Hypertens. 1997;15 Suppl 1:S31–S38. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715011-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANACORA G., KERSHAW M., FINKELSTEIN J.A., WHITE J.D. Increased hypothalamic content of preproneuropeptide Y mRNA in genetically obese Zucker rats and its regulation by food deprivation. Endocrinol. 1990;127:730–737. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-2-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAWCHENKO P.E., SWANSON L.W., GRZAMMA R., HOWE P.R.C., BLOOM S.R., POLAK J.M. Colocalisation of neuropeptide Y immunoreactivity in brainstem catecholaminergic neurons that project to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. J. Comp. Neural. 1985;241:138–153. doi: 10.1002/cne.902410203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHWARTZ M.W., FIGLEWICZ D.P., BASKIN D.G., WOODS S.C., PORTE D. Insulin in the brain: a hormonal regulator of energy balance. Endocrine. Rev. 1992;13:387–414. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-3-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHWARTZ M.W., SEELEY R.J., CAMPFIELD L.A., BURN P., BASKIN D.G. Identification of targets of leptin action in rat hypothalamus. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;98:1101–1106. doi: 10.1172/JCI118891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOLIN M.S., BALL M.J., ROBERTSON I., SILVA A., PASCO J.A., KOTOWICZ M.A., NICHOLSON G.C., COLLIER G.R. Relationship of serum leptin to total and truncal body fat. Clin. Sci. 1997;93:581–584. doi: 10.1042/cs0930581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STANLEY B.G., KYRKOULI S.E., LAMPERT S., LEIOBOWITZ S.F. NPY chronically injected into the hypothalamus: a powerful neurochemical inducer of hyperphagia and obesity. Peptides. 1986;7:1189–1192. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(86)90149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STRACK A.M., SEBASTIAN R.J., SCHWARTZ M.W., DALLMAN M.F. Glucocorticoids and insulin: reciprocal signals for energy balance. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:R142–R149. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.1.R142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAYHURN P. Brown adipose tissue: from thermal physiology to bioenergetics. J. Biosci. 1993;18:161–173. [Google Scholar]

- TRAYHURN P., DUNCAN J.S. Rapid chemiluminescent detection of the mRNA for uncoupling protein in brown adipose tissue by Northern hybridization with a 32-mer oligonucleotide end-labelled with digoxigenin. Int. J. Obesity. 1994;18:449–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAYHURN P., DUNCAN J.S., RAYNER D.V. Acute cold-induced suppression of ob (obese) gene expression in white adipose tissue of mice: mediation by the sympathetic system. Biochem. J. 1995;311:729–733. doi: 10.1042/bj3110729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS G., GILL J.S., LEE Y.C., CARDOSO H.M., OKPERE B.E., BLOOM S.R. Increased neuropeptide Y concentrations in specific hypothalamic regions of streptozocin-induced diabetic rats. Diabetes. 1989;38:321–327. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZARJEVSKI N., CUSIN I., VETTOR R., ROHNER-JEANRENAUD F., JEANRENAUD B. Intracerebroventricular administration of neuropeptide Y to normal rats has divergent effects on glucose utilization by adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 1994;43:764–769. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.6.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZIEGLER D., HAXHIU M.A., KAAN E.C., PAPP J.G., ERNSBERGER P. Pharmacology of moxonidine, an I1-imidazoline receptor agonist. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1996;27 Suppl 3:S26–S37. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199627003-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]