Abstract

The major nitroimine insecticide imidacloprid (IMI) and the nicotinic analgesics epibatidine and ABT-594 contain the 6-chloro-3-pyridinyl moiety important for high activity and/or selectivity. ABT-594 has considerable nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AChR) subtype specificity which might carry over to the chloropyridinyl insecticides. This study considers nine IMI analogues for selectivity in binding to immuno-isolated α1, α3 and α7 containing nicotinic AChRs and to purported α4β2 nicotinic AChRs.

α1- and α3-Containing nicotinic AChRs (both immuno-isolated by mAb 35, from Torpedo and human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells, respectively) are between two and four times more sensitive to DN-IMI than to (−)-nicotine.

With immuno-isolated α3 nicotinic AChRs, the tetrahydropyrimidine analogues of IMI with imine or nitromethylene substituents are 3–4 fold less active than (−)-nicotine. The structure-activity profile with α3 nicotinic AChRs from binding assays is faithfully reproduced in agonist potency as induction of 86rubidium ion efflux in intact cells.

α7-Containing nicotinic AChRs of SH-SY5Y cells (immuno-isolated by mAb 306) and rat brain membranes show maximum sensitivity to the tetrahydropyrimidine analogue of IMI with the nitromethylene substituent.

The purported α4β2 nicotinic AChRs [mouse (Chao & Casida, 1997) and rat brain] are similar in sensitivity to DN-IMI, the tetrahydropyrimidine nitromethylene and nicotine.

The commercial insecticides (IMI, acetamiprid and nitenpyram) have low to moderate potency at the α3 and purported α4β2 nicotinic AChRs and are essentially inactive at α1 and α7 nicotinic AChRs.

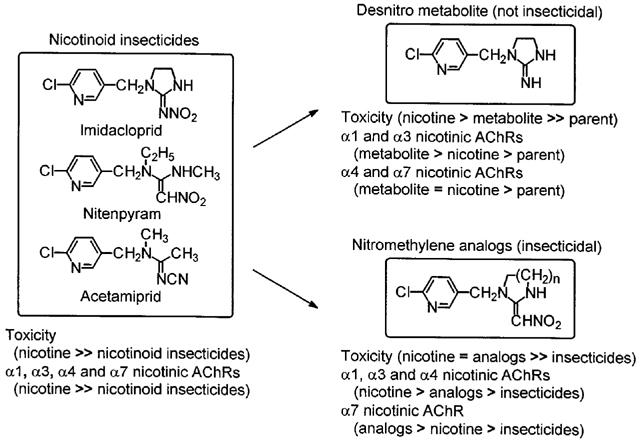

In conclusion, the toxicity of the analogues and metabolites of nicotinoid insecticides in mammals may involve action at multiple receptor subtypes with selectivity conferred by minor structural changes.

Keywords: Chloropyridinyl nicotinic ligands, human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells, imidacloprid, nicotinic AChR subtypes, nicotinoid insecticides, 86Rb+ efflux

Introduction

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) consist of diverse subtypes formed from five homologous subunits in combinations from nine α, four β, γ, δ and ε subunits. Advances in knowledge of nicotinic AChR structure and function provide a means to establish the specific receptor subtypes conferring selectivity for nicotinic drugs. The 6-chloro-3-pyridinyl moiety is present in some of the most potent and/or selective nicotinic agonists as to subtype specificity, e.g. the analgesics epibatidine and ABT-594 (Badio & Daly, 1994; Holladay et al., 1997; Bannon et al., 1998), and it is also important in a new class of synthetic nicotinoid insecticides (Shiokawa et al., 1995) (Figure 1). Imidacloprid (IMI) is the best known example of these highly effective new insecticides and others are acetamiprid (AAP) and nitenpyram (NTP) (Figure 2). These nicotinoid insecticides and their analogues might also be selective in their action on nicotinic AChR subtypes.

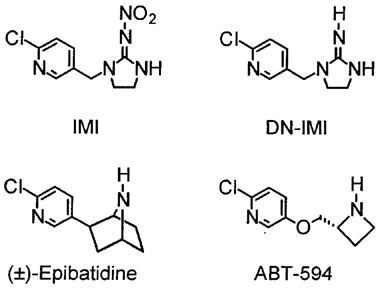

Figure 1.

Structural similarity between 6-chloro-3-pyridinyl-containing nicotinic ligands. Imidacloprid (IMI) is an insecticide and desnitro-imidacloprid (DN-IMI) is one of its metabolites. Epibatidine (from the skin of an Ecuadorian frog) and ABT-594 (from structure-activity optimization studies) are analgesics of outstanding potency and/or nicotinic AChR subtype specificity.

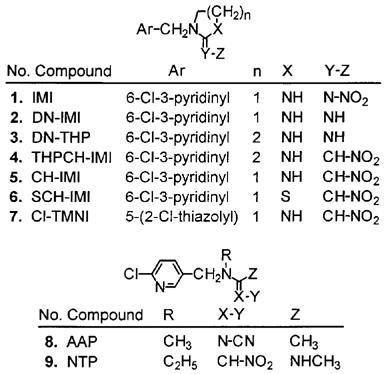

Figure 2.

Nicotinoid insecticides (1, 8 and 9) and a metabolite (2) and analogues (3–7). Eight of the compounds contain the 6-chloro-3-pyridinyl substituent with a methylene bridge to an imidazolidine (IMI, DN-IMI, CH-IMI and Cl-TMNI), tetrahydropyrimidine (DN-THP and THPCH-IMI), thiazolidine (SCH-IMI) or acyclic replacement for the heterocyclic ring (AAP and NTP). They include nitroimines (N-NO2), imines (NH), nitromethylenes (CH-NO2) and a cyanoimine (N-CN). A chlorothiazole moiety replaces the chloropyridine in Cl-TMNI. All of these chemicals, except DN-IMI and DN-THP, are highly potent insecticides.

α1-Containing nicotinic AChRs expressed in skeletal muscle and Torpedo electric organ are α1γ(or ε in adult)α1δβ1 heteromers; they are the best understood nicotinic AChRs as to the ligand binding site environment (Karlin & Akabas, 1995; Arias, 1997). Neuronal nicotinic AChR subtypes in brain and ganglia are assembled in combinations of α2–9 and β2–4 subunits and are pharmacologically classified into two main groups based on sensitivity to α-bungarotoxin (α-BGT) (Sargent, 1993; Lindstrom, 1997). The α-BGT-insensitive subtypes are formed from combinations of α2, α3, α4 and α6 with β2 or β4 subunits (sometimes with α5 or β3). The most prominent subtype of this group is α4β2 which represents >90% of high affinity tritiated agonist binding sites in brain (Whiting & Lindstrom, 1986; Flores et al., 1992). α3-Containing nicotinic AChRs (α3β4α5 and α3β2α5) are expressed in peripheral ganglia and limited regions of the brain (Conroy & Berg, 1995; Lindstrom, 1997). α-BGT-sensitive neuronal nicotinic AChR subtypes have α7, α8 and α9 subunits (Lindstrom, 1997). The abundance of α7-containing nicotinic AChRs in brain is comparable to that of the α4β2 subtype (Clarke et al., 1985; Whiting & Lindstrom, 1988; Lindstrom, 1997). The α7 nicotinic AChRs are also coexpressed with multiple α3-containing receptors (α3β4α5 and α3β2α5) in ganglia as well as in human neuroblastoma cells such as SH-SY5Y (Lukas et al., 1993; Peng et al., 1994; Lindstrom, 1997). The α8 subunit is found only in chickens and the α9 in limited regions of the rat nervous system (Schoepfer et al., 1990; Keyser et al., 1993; Elgoyhen et al., 1994). The native α7-containing nicotinic AChRs are considered to be assembled either as a homomer (Couturier et al., 1990; Chen & Patrick, 1997; Lindstrom, 1997) or as heteromers with unknown subunit(s) (Whiting & Lindstrom, 1987; Gotti et al., 1991; Anand et al., 1993b).

The structure and function of insect nicotinic AChRs have been investigated with biochemical, molecular biological and immunohistochemical approaches but are poorly understood relative to those of animals. Although several candidate genes encoding the α and non-α subunits are identified from fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) and migratory locusts (Locusta migratoria), their functional coexpression has not been successful in any combination, implying the involvement of unidentified subunit(s) in assembling the native insect receptors (Gundelfinger & Hess, 1992; Tomizawa et al., 1996; 1999; Tomizawa & Casida, 1997; Hermsen et al., 1998). Interestingly, functional ion channel properties are clearly observed when either of two Drosophila α type subunits is coexpressed with chick β2 subunit and the two reconstituted Drosophila α/chick β receptors display different sensitivities to α-BGT (Bertrand et al., 1994). It is proposed for the cockroach (Periplaneta americana) that the α-BGT-sensitive and -insensitive nicotinic AChRs are expressed in the dorsal unpaired median neurons and that both subtypes are affected by IMI, based on electrophysiology studies (Lapied et al., 1990; Buckingham et al., 1997).

IMI and its desnitro metabolite (DN-IMI) (Figure 1) differ greatly in binding site specificity: IMI is highly potent at insect but not mammalian nicotinic AChRs (Liu & Casida, 1993; Zwart et al., 1994; Yamamoto et al., 1998) whereas DN-IMI is much more active in mammals than insects (Liu et al., 1993; Chao & Casida, 1997; Nauen et al., 1998). On this basis, minor structural variations in nicotinoid insecticides may also alter the subtype specificity for mammalian nicotinic AChRs. The objective of this study is to determine the contribution of α1-, α3-, α7- and α4β2-containing nicotinic AChRs to the specificity of nicotinoid insecticide action.

Methods

Chemicals

Structures and abbreviations for the nicotinoids studied are given in Figure 2. They were available from our previous studies (Liu et al., 1995; Tomizawa et al., 1996; Chao & Casida, 1997) except for DN-THP which was synthesized by a procedure analogous to that used for DN-IMI (Latli et al., 1996). The purity of these compounds was >95% and they were stored in amber bottles (under nitrogen atmosphere if needed) at room temperature, and the test sample was freshly prepared for each experiment.

Sources for other chemicals were as follows: (3-[125I]iodotyrosyl)α-BGT ([125I]α-BGT, >277 Ci mmol−1) and 86rubidium chloride (1.7 mCi mg−1 Rb, 86Rb+) from Amersham Life Science (Arlington Heights, IL, U.S.A.); L-[N-methyl-3H]-nicotine ([3H]-nicotine, 81.5 Ci mmol−1) from NEN Life Science Products (Boston, MA, U.S.A.); α-BGT, (−)-nicotine hydrogen tartrate and poly-L-lysine hydrobromide from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.); Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), foetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin from Gibco Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, U.S.A.). The nicotinic AChR monoclonal antibodies (mAb) used were mAb 35 against α1, α3 and α5 subunits (Conroy et al., 1992) and mAb 306 against the α7 subunit (Schoepfer et al., 1990) from Research Biochemicals International (Natick, MA, U.S.A.).

Torpedo receptor preparation

Torpedo electric organ (Biofish Associates, Georgetown, MA, U.S.A.) was homogenized in four volumes of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing (in mM): NaCl 1000, EDTA 5, EGTA 5, phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride (PMSF) 2, benzamidine 5 and iodoacetamide 5 at 4°C using a Polytron for three 30 s periods with 60 s intervals in between. The homogenate was filtered through four layers of cheesecloth and the filtrate was centrifuged at 40,000×g for 30 min at 4°C. The pellet was suspended in lysis buffer (in mM): sodium phosphate (pH 7.5) containing 2% Triton X-100 50, NaCl 50, EDTA 5, EGTA 5, PMSF 2, benzamidine 5 and iodoacetamide 5 (same volume as the homogenate) and the suspension was solubilized by rotation on a rocking platform for 60 min at 4°C. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 40,000×g for 30 min at 4°C.

Human neuroblastoma cell receptor preparation

Cultures of SH-SY5Y cells (Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of California, Berkeley) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 u ml−1 penicillin and 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere with a medium change every 2–3 days. The cells were harvested with a cell lifter in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, NaCl 100 mM, sodium phosphate buffer 10 mM, pH 7.5). The harvested cells were disrupted by brief vortexing in five volumes of lysis buffer as above. After 20 min gentle rotation on a rocking platform at 4°C, the sample was centrifuged for 20 min at 4°C in an Eppendorf microcentrifuge and the supernatant was recovered.

Radioligand binding

Supernatants from Torpedo electric organ or SH-SY5Y cell preparations were used for immuno-isolation of receptor subtypes (Anand et al., 1993a; Peng et al., 1997) then radioligand binding assay. mAb 35 or 306 (immunoglobulin at 5 mg ml−1) was coupled to Immulon 4HBX Removawells (Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, VA, U.S.A.) by incubating 4–5 μg mAb (per well) in 0.1 ml of 10 mM sodium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.8) overnight at 4°C. After three washes with 0.2 ml of the bicarbonate buffer, the wells were quenched with 0.2 ml of 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS-Tween 20 buffer (0.05% Tween 20 in PBS) for 4 h at 4°C. The wells were then washed three times with 0.2 ml of the PBS-Tween 20. The receptor preparation (0.1 ml) was added to each mAb-precoated well and incubated overnight at 4°C. The wells were washed three times with 0.2 ml of the PBS-Tween 20 buffer and then treated with various concentrations of test compound for 20 min. Radioligand binding assay was initiated by addition to this medium of [3H]-nicotine (20 nM for α3 nicotinic AChRs) or [125I]-α-BGT (0.2 nM for α1 nicotinic AChRs or 2 nM for α7 nicotinic AChRs) and incubation in 0.1 ml final volume for 60 min (for [3H]-nicotine binding) or overnight (for [125I]-α-BGT binding) at 25 or 4°C, respectively. The wells were then rinsed three times with 0.2 ml PBS-Tween 20 buffer and the radioactivity remaining was subjected to liquid scintillation counting. Every experiment included (−)-nicotine as a standard at 50 nM (for α3 nicotinic AChRs with [3H]-nicotine) or 10 μM (for α7 nicotinic AChRs with [125I]-α-BGT). Background binding was determined using wells lacking mAb. For comparison, the binding affinity for (−)-nicotine in [3H]-nicotine binding to immuno-isolated α3 receptors from SH-SY5Y cells is 0.02 μM (Peng et al., 1997), and for α-BGT and (−)-nicotine in [125I]-α-BGT binding to immuno-isolated α7 receptors from the same cells are 0.00106 and 2.6 μM, respectively (Peng et al., 1994).

Membranes from male rat whole brain were prepared and assayed for 2 nM [125I]-α-BGT binding by the method of Marks et al. (1986) and for 5 nM [3H]-nicotine binding as described by Yamamoto et al. (1995). Data for [3H]-nicotine binding to mouse brain membranes are from Chao & Casida (1997).

86Rb+ efflux assay

Agonist-induced cation flux in SH-SY5Y cells has been attributed to α3-containing nicotinic AChRs; α-BGT-sensitive receptors do not contribute detectably to the ion flux measured in this assay (Lukas et al., 1993). SH-SY5Y cells were therefore used to assay α3-containing receptor function by the procedure of Lukas (1989) with minor modification. The cells were seeded in 24-well (18.5 mm diameter) culture plates at a density of 106 cells well−1 following the coating of each well by treatment with poly-L-lysine (30 μg ml−1) then aspiration off. At confluence, the cells attached to the culture plates were loaded with 0.2 μCi of 86Rb+ in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 u ml−1 penicillin and 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin (0.5 ml) and incubated overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere. The medium containing 86Rb+ was removed by aspiration, the cells were rinsed twice with 0.5 ml of fresh medium and then exposed to 0.25 ml of medium with or without a test compound for 5 min. (−)-Nicotine (0.1 mM) was tested as a standard in each experiment. After exposure to the test compound, the assay medium was immediately transferred into a vial for Cerenkov counting. For validation in a preliminary experiment, we confirmed that 0.1 mM d-tubocurarine gave 97–100% blockage of 86Rb+ efflux induced by 0.1 mM (−)-nicotine as reported by Lukas et al. (1993).

Data calculation

IC50 (molar concentration of test compound for 50% inhibition of specific radioligand binding) and EC50 [molar concentration of test compound to induce 50% specific 86Rb+ efflux relative to 0.1 mM (−)-nicotine] values were determined by iterative nonlinear least-squares regression using the SigmaPlot program (Jandel Scientific Software, San Rafael, CA, U.S.A.).

Toxicity

Male albino Swiss-Webster mice (20–25 g) were treated i.p. with the test compounds dissolved in water or dimethyl sulphoxide with mortality observations at 24 h as described by Chao & Casida (1997). Toxicity data are from Chao & Casida (1997) for seven compounds and the present determination for three compounds. These studies were carried out in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the United States National Institutes of Health.

Results

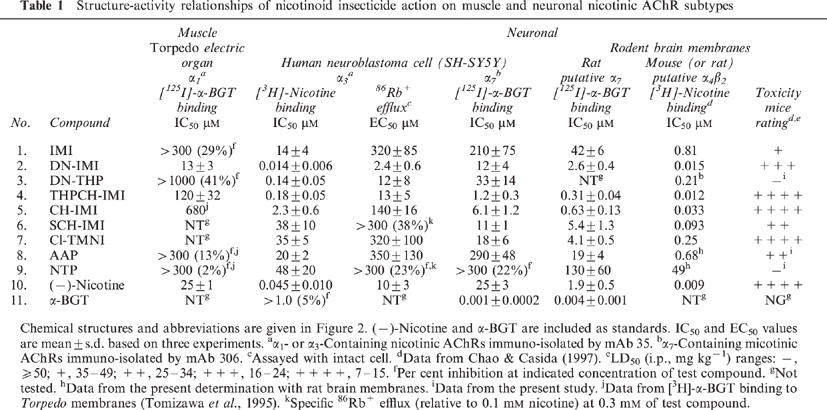

Interaction with α1 nicotinic AChRs

The Torpedo electric organ was used as the source of α1 nicotinic AChRs with immuno-isolation by mAb 35 and binding assay with [125I]-α-BGT. DN-IMI is 2 fold more potent than nicotine with IC50 values of 13 and 25 μM, respectively (Table 1). THPCH-IMI has low activity (IC50 120 μM) and all the other nicotinoids are essentially inactive (Table 1).

Table 1.

Structure-activity relationships of nicotinoid insecticide action on muscle and neuronal nicotinic AChR subtypes

Interaction with α3 nicotinic AChRs

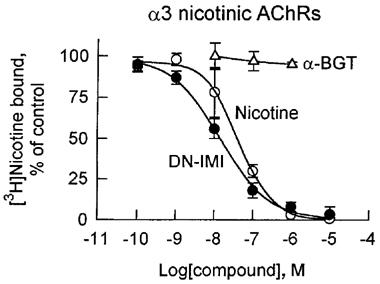

Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells express multiple α3β2β4α5 nicotinic AChRs; the α3 receptors were immuno-isolated with mAb 35 for [3H]-nicotine binding. DN-IMI is the most potent compound (IC50 0.014 μM) and nicotine is 3 fold less active (Figure 3, Table 1). The potency order for the other nicotinoids is DN-THP and THPCH-IMI (IC50 0.14–0.18 μM)>CH-IMI (IC50 2.3 μM)>IMI, AAP, Cl-TMNI, SCH-IMI and NTP (IC50 14–48 μM) (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Displacement by DN-IMI and (−)-nicotine of [3H]-nicotine binding to α-BGT-insensitive α3 nicotinic AChRs immuno-isolated from human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. The extracted cell membranes with lysis buffer were reacted with mAb 35-precoated wells overnight at 4°C, and then the immunoprecipitated α3 nicotinic AChRs were incubated for 60 min at 25°C with 20 nM of [3H]-nicotine in competition with a test compound. Data points represent means of three experiments with s.d.

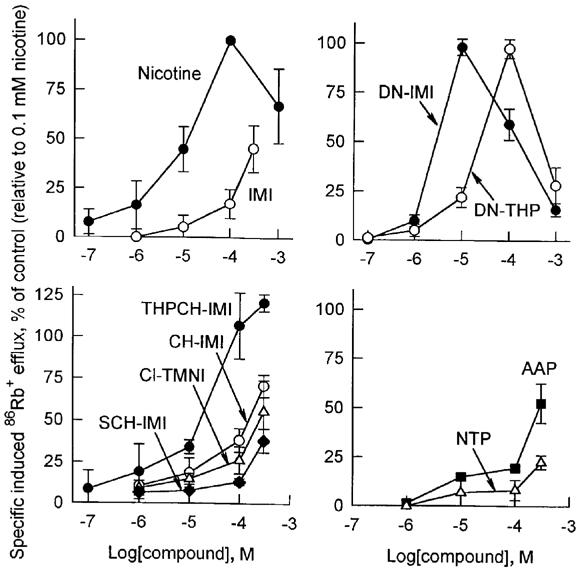

Induced 86Rb+ efflux with intact SH-SY5Y cells provides another means to evaluate nicotinoid agonist effect attributable to α3-containing receptor function. DN-IMI with an EC50 of 2.4 μM is 4–5 fold more potent than nicotine, DN-THP and THPCH-IMI (EC50 10–13 μM), and DN-IMI and DN-THP display steep efflux induction curves (Table 1, Figure 4). THPCH-IMI induces higher 86Rb+ efflux than that induced by 0.1 mM (−)-nicotine. The remaining chemicals do not induce an efflux response that reaches the maximum of the nicotine standard.

Figure 4.

Induction by nicotinoids of specific 86Rb+ efflux from intact human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Data for agonist potency are given on a percentage basis relative to 0.1 mM (−)-nicotine as 100% in the same experiment. The intact SH-SY5Y cells preloaded with 0.2 μCi of 86Rb+ were exposed to medium with or without a test agonist for 5 min. The value for the (−)-nicotine standard ranged from 6000–7000 c.p.m. versus a background without agonist of 1000–1200 c.p.m. Data points represent means of three experiments with s.d.

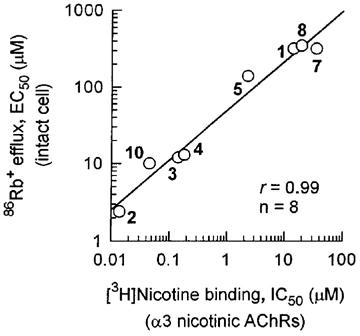

The inhibitory potency of eight nicotinoids with immuno-isolated α3 nicotine AChRs of SH-SY5Y cells is highly correlated (r=0.99) with that for agonist-induced 86Rb+ efflux from intact cells (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Correlation for nicotinoids of inhibitory potency for [3H]-nicotine binding to immuno-isolated α3 nicotinic AChRs and of agonist potency to induce specific 86Rb+ efflux in cultured human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Numbers on graph refer to compounds in Figure 2 and Table 1.

Interaction with α7 nicotinic AChRs

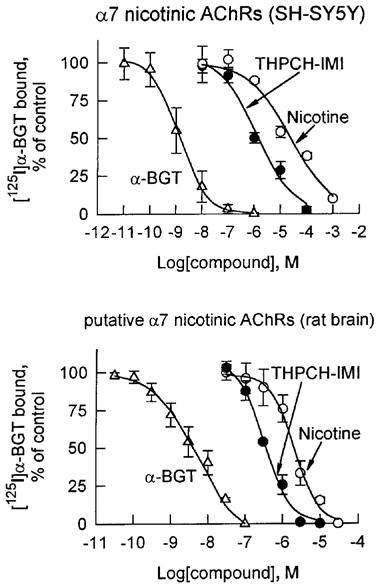

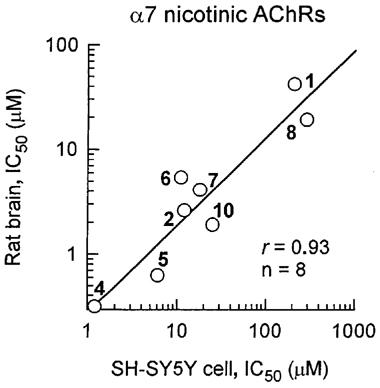

[125I]-α-BGT binding was determined to mAb 306 immuno-isolated α7 nicotinic AChRs of SH-SY5Y cells and in putative α7 nicotinic AChRs of rat brain membranes. The α7 nicotinic AChRs of the human neuroblastoma cells are most sensitive to THPCH-IMI (Figure 6) and then CH-IMI (IC50s 1.2 and 6.1 μM, respectively), least sensitive to IMI, AAP and NTP (IC50s 210–>300 μM) and with intermediate sensitivity to nicotine and the other five nicotinoids (IC50s 11–33 μM) (Table 1). The same structure-activity relationships are obtained with the several-fold more sensitive rat brain putative α7 nicotinic AChR (Figure 6 and Table 1) as clearly apparent by a correlation plot for inhibition of the SH-SY5Y and rat brain receptors (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Displacement by THPCH-IMI, (−)-nicotine and α-BGT of [125I]-α-BGT binding to α7 nicotinic AChRs immuno-isolated from human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (top) and to putative α7 nicotinic AChRs from rat whole brain membranes (bottom). The extracted cell membranes with lysis buffer were reacted with mAb 306-precoated wells overnight at 4°C, and then the immunoprecipitated α7 nicotinic AChRs were incubated overnight at 4°C with 2 nM of [125I]-α-BGT in competition with a test compound. Rat whole brain membranes (200 μg protein) were incubated with 2 nM of [125I]-α-BGT for 4 h at 37°C in the absence and the presence of the test compound. Data points represent means of three experiments with s.d.

Figure 7.

Correlation for nicotinoids of inhibitory potency for [125I]-α-BGT binding to immuno-isolated α7 nicotinic AChRs from human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells and to putative α7 nicotinic AChRs from rat brain membranes. Numbers on graph refer to compounds in Figure 2 and Table 1.

Interaction with putative α4β2 nicotinic AChRs

[3H]-Nicotine binding in mouse or rat brain membranes was used to determine putative α4β2 nicotinic AChRs. Data for mouse [3H]-nicotine binding were taken from our previous report (Chao & Casida, 1997). There are four potent inhibitors in this assay (IC50 0.009–0.033 μM for nicotine, THPCH-IMI, DN-IMI and CH-IMI) with moderate activity for SCH-IMI, DN-THP and Cl-TMNI (IC50 0.093–0.25 μM), lower activity for IMI and AAP and the lowest activity for NTP.

Toxicity

The i.p. toxicity rating in mice of two chloropyridinyl compounds (CH-IMI and THPCH-IMI) and one chlorothiazolyl compound (Cl-TMNI) is similar to that of nicotine while DN-IMI is a little less toxic than nicotine and the others are much less active (Table 1). The poisoning signs at an LD50 dose included tremors and seizures and appeared to be consistent with action on nicotinic AChRs.

Discussion

The chloropyridinyl nicotinoid insecticide IMI has little or no activity in vertebrate systems based on six observations: (1) the failure to recognize [3H]-IMI specific binding site(s) in brain from several mammalian and avian species and the electric eel (Liu & Casida, 1993); (2) low potency as an inhibitor of [3H]-α-BGT binding and low agonistic effect in muscle-type nicotinic AChR from Torpedo electric organ (not only for IMI but also for AAP and NTP) (Tomizawa et al., 1995); (3) little activity as an inhibitor of [3H]-nicotine binding to rat and mouse brain membranes (Yamamoto et al., 1995; Chao & Casida, 1997); (4) very weak agonistic action in mouse N1E-115 neuroblastoma and BC3H1 muscle cells (IMI and an analogue) (Zwart et al., 1992; 1994); (5) low activity in ion channel activation compared to acetylcholine with rat α4β2 and α7 subtypes expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Yamamoto et al., 1998); (6) weak or partial agonistic nature with recombinant chick α4β2 receptor (Matsuda et al., 1998). The present study extends these relationships for IMI, AAP and NTP to include very low apparent affinity to α1, α3 and α7 nicotinic AChR subtypes. However, these conclusions are based only on the parent insecticide which might undergo metabolic activation such as the case of IMI to DN-IMI (Klein, 1994; Chao & Casida, 1997). The imine metabolite DN-IMI is much more effective than the parent IMI, not only for putative α4β2 receptors (Chao & Casida, 1997) but also for α1, α3 and α7 nicotinic AChRs (this study).

The chloropyridinyl group is an important structural feature for several nicotinic agonists conferring outstanding potency but little selectivity with epibatidine (Holladay et al., 1997) and remarkable α4β2 nicotinic AChR specificity with ABT-594 (Bannon et al., 1998). The binding affinities of analogues without the chlorine atom in the insect receptor are several-fold less than those with the chlorine atom (Liu et al., 1993; Tomizawa & Yamamoto, 1993). The chlorothiazolyl replacement for the chloropyridinyl moiety (Cl-TMNI versus CH-IMI) greatly reduces potency in the mammalian receptor assays but not the toxicity to mammals or activity at the insect nicotinic AChR (Liu et al., 1993; Chao & Casida, 1997).

Differential nicotinic AChR subtype selectivity is conferred by minor structural changes in the chloropyridinyl nicotinoid insecticides (Figure 8). The desnitro analogues favour the α1, α3 and putative α4β2 receptor subtypes and the nitromethylene analogues the α7 nicotinic AChRs. THPCH-IMI and CH-IMI are much more potent than nicotine on α7 nicotinic AChRs while SCH-IMI and Cl-TMNI are less active than the first two compounds. All four of these nitromethylenes are much less active than nicotine on α1 and α3 nicotinic AChRs. Interestingly, the two desnitro analogues DN-IMI and DN-THP prefer the α3 over the α7 nicotinic AChRs. The change from a five-membered imidazolidine to a six-membered tetrahydropyrimidine ring greatly reduces the potency of the imines (DN-IMI versus DN-THP) but increases the activity of the nitromethylenes (CH-IMI versus THPCH-IMI) in all nicotinic AChR subtypes.

Figure 8.

Toxicity of nicotinoid insecticides and selected analogues in mammals involves differential action at multiple receptor subtypes conferred by minor structural changes. The potency rankings in parentheses are generalizations.

The mammalian toxicity of the nicotinoid insecticides and analogues studied on an overall basis is most closely related to their potency at α7 nicotinic AChRs with decreasing relationships sequentially at the α4β2, α3 and α1 nicotinic AChRs. More specifically, the nitromethylenes are more potent in the α7-containing receptors while DN-IMI is particularly potent at α1, α3 and putative α4β2 receptors (Figure 8). Thus, the toxicity of the nicotinoid insecticides in mammals may involve action at multiple receptor subtypes with selectivity conferred by minor structural changes.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Grant Nos. P01 ES00049 and R01 ES08424 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), NIH, and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIEHS, NIH. We thank our laboratory colleagues Weiwei Li, Kevin D'Amour, Susan Sparks, Michihiro Kamijima and Gary Quistad for valuable advice and assistance. Special acknowledgement is given to Bachir Latli for synthesis of DN-THP and most of the other nicotinoids used.

Abbreviations

- AAP

acetamiprid

- AChR

acetylcholine receptor

- α-BGT or [125I]α-BGT

α-bungarotoxin or its 125-iodine labelled ligand

- CH-IMI

nitromethylene analogue of IMI

- Cl-TMNI

chlorothiazolyl analogue of CH-IMI

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- DN-IMI

desnitro metabolite of IMI

- DN-THP

tetrahydropyrimidine analogue of DN-IMI

- EC50

molar concentration of test compound to induce 50% specific 86Rb+ efflux

- FBS

foetal bovine serum

- IC50

molar concentration of test compound for 50% inhibition of specific radioligand binding

- IMI

imidacloprid

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- NTP

nitenpyram

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PMSF

phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride

- 86Rb+

86rubidium ion

- SCH-IMI

thiazolidine analogue of CH-IMI

- THPCH-IMI

tetrahydropyrimidine analogue of CH-IMI

References

- ANAND R., PENG X., BALLESTA J.J., LINDSTROM J. Pharmacological characterization of α-bungarotoxin-sensitive acetylcholine receptors immunoisolated from chick retina: contrasting properties of α7 and α8 subunit-containing subtypes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993a;44:1046–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANAND R., PENG X., LINDSTROM J. Homomeric and native α7 acetylcholine receptors exhibit remarkably similar but non-identical pharmacological properties, suggesting that the native receptor is a heteromeric protein complex. FEBS Lett. 1993b;327:241–246. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80177-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARIAS H.R. Topology of ligand binding sites on the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Brain Res. Rev. 1997;25:133–191. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BADIO B., DALY J.W. Epibatidine, a potent analgetic and nicotinic agonist. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:563–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BANNON A.W., DECKER M.W., HOLLADAY M.W., CURZON P., DONNELLY-ROBERTS D., PUTTFARCKEN P.S., BITNER R.S., DIAZ A., DICKENSON A.H., PORSOLT R.D., WILLIAMS M., ARNERIC S.P. Broad-spectrum, non-opioid analgesic activity by selective modulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Science. 1998;279:77–81. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5347.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERTRAND D., BALLIVET M., GOMEZ M., BERTRAND S., PHANNAVONG B., GUNDELFINGER E.D. Physiological properties of neuronal nicotinic receptors reconstituted from the vertebrate β2 subunit and Drosophila α subunits. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1994;6:869–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUCKINGHAM S.D., LAPIED B., LE CORRONC H., GROLLEAU F., SATTELLE D.B. Imidacloprid actions on insect neuronal acetylcholine receptors. J. Exp. Biol. 1997;200:2685–2692. doi: 10.1242/jeb.200.21.2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAO S.L., CASIDA J.E. Interaction of imidacloprid metabolites and analogs with the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor of mouse brain in relation to toxicity. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1997;58:77–78. [Google Scholar]

- CHEN D.N., PATRICK J.W. The α-bungarotoxin-binding nicotinic acetylcholine receptor from rat brain contains only the α7 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:24024–24029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.24024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARKE P.B.S., SCHWARTZ R.D., PAUL S.M., PERT C.B., PERT A. Nicotinic binding in rat brain: Autoradiographic comparison of [3H]acetylcholine, [3H]nicotine, and [125I]-α-bungarotoxin. J. Neurosci. 1985;5:1307–1315. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-05-01307.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONROY W.G., BERG D.K. Neurons can maintain multiple classes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors distinguished by different subunit composition. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:4424–4431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONROY W.G., VERNALLIS A.B., BERG D.K. The α5 gene product assembles with multiple acetylcholine receptor subunits to form distinctive receptor subtypes in brain. Neuron. 1992;9:679–691. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COUTURIER S., BERTRAND D., MATTER J.-M., HERNANDEZ M.-C., BERTRAND S., MILLAR N., VALERA S., BARKAS T., BALLIVET M. A neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit (α7) is developmentally regulated and forms a homo-oligomeric channel blocked by α-BTX. Neuron. 1990;5:847–856. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90344-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELGOYHEN A.B., JOHNSON D.S., BOULTER J., VETTER D.E., HEINEMANN S. α9: An acetylcholine receptor with novel pharmacological properties in rat cochlear hair cells. Cell. 1994;79:705–715. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLORES C.M., ROGERS S.W., PABREZA L.A., WOLFE B.B., KELLAR K.J. A subtype of nicotinic cholinergic receptor in rat brain is composed of α4 and β2 subunits and is up-regulated by chronic nicotine treatment. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992;41:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOTTI C., OGANDO A.E., HANKE W., SCHLUE R., MORETTI M., CLEMENTI F. Purification and characterization of an α-bungarotoxin receptor that forms a functional nicotinic channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:3258–3262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUNDELFINGER E.D., HESS N. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors of the central nervous system of Drosophila. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1992;1137:299–308. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(92)90150-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERMSEN B., STETZER E., THEES R., HEIERMANN R., SCHRATTENHOLZ A., EBBINGHAUS U., KRETSCHMER A., METHFESSEL C., REINHARDT S., MAELICKE A. Neuronal nicotinic receptors in the locust Locusta migratoria – cloning and expression. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:18394–18404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLADAY M.W., DART M.J., LYNCH J.K. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as targets for drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 1997;40:4169–4194. doi: 10.1021/jm970377o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARLIN A., AKABAS M.H. Toward a structural basis for the function of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and their cousins. Neuron. 1995;15:1231–1244. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEYSER K.T., BRITTO L.R.G., SCHOEPFER R., WHITING P., COOPER J., CONROY W., BROZOZOWSKA-PRECHTL A., KARTEN H.J., LINDSTROM J. Three subtypes of α-bungarotoxin-sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are expressed in chick retina. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:442–454. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00442.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEIN O.The metabolism of imidacloprid in animals Eighth IUPAC International Congress of Pesticide Chemistry 1994Washington, DC; July [Abstract 367] [Google Scholar]

- LAPIED B., LE CORRONC H., HUE B. Sensitive nicotinic and mixed nicotinic-muscarinic receptors in insect neurosecretory cells. Brain Res. 1990;533:132–136. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91805-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LATLI B., THAN C., MORIMOTO H., WILLIAMS P.G., CASIDA J.E. [6-chloro-3-pyridylmethyl-3H]Neonicotinoids as high-affinity radioligands for the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: preparation using NaB3H4 and LiB3H4. J. Labelled Compounds Radiopharmaceut. 1996;38:971–978. [Google Scholar]

- LINDSTROM J. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in health and disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 1997;15:193–222. doi: 10.1007/BF02740634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU M.-Y., CASIDA J.E. High affinity binding of [3H]imidacloprid in the insect acetylcholine receptor. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1993;40:40–46. [Google Scholar]

- LIU M.-Y., LANFORD J., CASIDA J.E. Relevance of [3H]imidacloprid binding site in house fly head acetylcholine receptor to insecticidal activity of 2-nitromethylene- and 2-nitroimino-imidazolidines. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1993;46:200–206. [Google Scholar]

- LIU M.-Y., LATLI B., CASIDA J.E. Imidacloprid binding site in Musca nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: interactions with physostigmine and a variety of nicotinic agonists with chloropyridyl and chlorothiazolyl substituents. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1995;52:170–181. [Google Scholar]

- LUKAS R.J. Pharmacological distinctions between functional nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on the PC12 rat pheochromocytoma and the TE671 human medulloblastoma. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989;251:175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUKAS R.J., NORMAN S.A., LUCERO L. Characterization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed by cells of the SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma clonal line. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 1993;4:1–12. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1993.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARKS M.J., STITZEL J.A., ROMM E., WEHNER J.M., COLLINS A.C. Nicotinic binding sites in rat and mouse brain: comparison of acetylcholine, nicotine, and α-bungarotoxin. Mol. Pharmacol. 1986;30:427–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUDA K., BUCKINGHAM S.D., FREEMAN J.C., SQUIRE M.D., BAYLIS H.A., SATTELLE D.B. Effects of the α subunit on imidacloprid sensitivity of recombinant nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123:518–524. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAUEN R., TIETJEN K., WAGNER K., ELBERT A. Efficacy of plant metabolites of imidacloprid against Myzus persicae and Aphis gossypii (Homoptera : Aphididae) Pestic. Sci. 1998;52:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- PENG X., GERZANICH V., ANAND R., WANG F., LINDSTROM J. Chronic nicotine treatment up-regulates α3 and α7 acetylcholine receptor subtypes expressed by the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;51:776–784. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.5.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PENG X., KATZ M., GERZANICH V., ANAND R., LINDSTROM J. Human α7 acetylcholine receptor: cloning of the α7 subunit from the SH-SY5Y cell line and determination of pharmacological properties of native receptors and functional α7 homomers expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:546–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARGENT P.B. The diversity of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1993;16:403–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.16.030193.002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHOEPFER R., CONROY W.G., WHITING P., GORE M., LINDSTROM J. Brain α-bungarotoxin binding protein cDNAs and MAbs reveal subtypes of this branch of the ligand-gated ion channel gene superfamily. Neuron. 1990;5:35–48. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90031-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIOKAWA K., TSUBOI S., MORIYA K., KAGABU S.Chloronicotinyl insecticides: development of imidacloprid Eighth International Congress of Pesticide Chemistry: Options 2000 1995Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 49–58.eds Ragsdale NN, Kearney PC & Plimmer JR. pp [Google Scholar]

- TOMIZAWA M., CASIDA J.E. [125I]Azidonicotinoid photoaffinity labeling of insecticide-binding subunit of Drosophila nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Neurosci. Lett. 1997;237:61–64. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00811-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOMIZAWA M., LATLI B., CASIDA J.E. Novel neonicotinoid-agarose affinity column for Drosophila and Musca nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Neurochem. 1996;67:1669–1676. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67041669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOMIZAWA M., LATLI B., CASIDA J.E.Structure and function of insect nicotinic acetylcholine receptors studied with nicotinoid insecticide affinity probes Nicotinoid insecticides and the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor 1999Tokyo: Springer-Verlag; eds Yamamoto, I. & Casida, J.E. in press [Google Scholar]

- TOMIZAWA M., OTSUKA H., MIYAMOTO T., YAMAMOTO I. Pharmacological effects of imidacloprid and its related compounds on the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with its ion channel from the Torpedo electric organ. J. Pesticide Sci. 1995;20:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- TOMIZAWA M., YAMAMOTO I. Structure-activity relationships of nicotinoids and imidacloprid analogs. J. Pesticide Sci. 1993;18:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- WHITING P., LINDSTROM J. Pharmacological properties of immuno-isolated neuronal nicotinic receptors. J. Neurosci. 1986;6:3061–3069. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-10-03061.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITING P., LINDSTROM J. Purification and characterization of a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor from rat brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, U.S.A. 1987;84:595–599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITING P.J., LINDSTROM J.M. Characterization of bovine and human neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors using monoclonal antibodies. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:3395–3404. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-09-03395.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAMOTO I., TOMIZAWA M., SAITO T., MIYAMOTO T., WALCOTT E.C., SUMIKAWA K. Structural factors contributing to insecticidal and selective actions of neonicotinoids. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 1998;37:24–32. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6327(1998)37:1<24::AID-ARCH4>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAMOTO I., YABUTA G., TOMIZAWA M., SAITO T., MIYAMOTO T., KAGABU S. Molecular mechanism for selective toxicity of nicotinoids and neonicotinoids. J. Pesticide. Sci. 1995;20:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- ZWART R., OORTGIESEN M., VIJVERBERG H.P.M. The nitromethylene heterocycle 1-(pyridin-3-yl-methyl)-2-nitromethylene-imidazolidine distinguishes mammalian from insect nicotinic receptor subtypes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;228:165–169. doi: 10.1016/0926-6917(92)90026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZWART R., OORTGIESEN M., VIJVERBERG H.P.M. Nitromethylene heterocycles: Selective agonists of nicotinic receptors in locust neurons compared to mouse N1E-115 and BC3H1 cells. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1994;48:202–213. [Google Scholar]