Abstract

It has been hypothesized that in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia, selective antagonism of the α1A-adrenoceptor-mediated contraction of lower urinary tract tissues may, via a selective relief of outlet obstruction, lead to an improvement in symptoms.

The present study describes the α1-adrenoceptor (α1-AR) subtype selectivities of two novel α1-AR antagonists, Ro 70-0004 (aka RS-100975) and a structurally-related compound RS-100329, and compares them with those of prazosin and tamsulosin. Radioligand binding and second-messenger studies in intact CHO-K1 cells expressing human cloned α1A-, α1B- and α1D-AR showed nanomolar affinity and significant α1A-AR subtype selectivity for both Ro 70-0004 (pKi 8.9: 60 and 50 fold selectivity) and RS-100329 (pKi 9.6: 126 and 50 fold selectivity) over the α1B- and α1D-AR subtypes respectively. In contrast, prazosin and tamsulosin showed little subtype selectivity.

Noradrenaline-induced contractions of human lower urinary tract (LUT) tissues or rabbit bladder neck were competitively antagonized by Ro 70-0004 (pA2 8.8 and 8.9), RS-100329 (pA2 9.2 and 9.2), tamsulosin (pA2 10.4 and 9.8) and prazosin (pA2 8.7 and 8.3 respectively). Affinity estimates for tamsulosin and prazosin in antagonizing α1-AR-mediated contractions of human renal artery (HRA) and rat aorta (RA) were similar to those observed in LUT tissues, whereas Ro 70-0004 and RS-100329 were approximately 100 fold less potent (pA2 values of 6.8/6.8 and 7.3/7.9 in HRA/RA respectively).

The α1A-AR subtype selectivity of Ro 70-0004 and RS-100329, demonstrated in both cloned and native systems, should allow for an evaluation of the clinical utility of a ‘uroselective' agent for the treatment of symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Keywords: α1-adrenoceptors, Ro 70-0004, RS-100329, prazosin, tamsulosin, prostate, rat aorta, human renal artery, radioligand binding, inositol phosphates

Introduction

Molecular and pharmacological studies have led to the division of α1-adrenoceptors into three subtypes: α1A-, α1B- and α1D-adrenoceptors (see Heible et al., 1995). An alternative subdivision has been proposed (Flavahan & VanHoutte, 1986; Muramatsu, 1992) based on α1-adrenoceptor affinities for prazosin in functional studies: i.e. α1H-adrenoceptors (high, subnanomolar affinity for prazosin; α1A-, α1B- and α1D-adrenoceptors) and α1L-adrenoceptors (low, suprananomolar affinity for prazosin). Other antagonists, including RS-17053 (Ford et al., 1996) and WB4101, are also reported to distinguish between the ‘classical' α1A-adrenoceptor and the α1L-adrenoceptor, displaying significantly lower affinity at the latter. However, the proposal of further subtypes has yet to be supported by molecular biological evidence. Indeed, it has been suggested that existing cloned subtypes may fully account for observations which led to the α1H versus α1L subdivision, in as much as cells expressing the human cloned α1A-adrenoceptor have been shown to exhibit an α1L-like pharmacology (see Ford et al., 1994; 1997; Williams et al., 1996).

Following earlier studies with the alkylating agent phenoxybenzamine (Caine et al., 1978), competitive α1-adrenoceptor antagonists such as terazosin (Lepor, 1995), prazosin (Hedlund et al., 1983; Chapple et al., 1992) and alfuzosin (Buzelin et al., 1993) have been shown to be effective in relieving urinary outflow obstruction and reducing symptom scores in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). However, the usefulness of α1-adrenoceptor antagonists in BPH is offset by their dose-limiting cardiovascular effects, including postural hypotension, particularly with initial dosing. The discovery and definition of α1-adrenoceptor subtypes offers the potential for more selective agents. Recently, interest has focused on the role of the α1A-adrenoceptor subtype in BPH, as a result of studies demonstrating that this subtype predominates in the urethra and prostate of man (Price et al., 1993; Faure et al., 1994; Taniguchi et al., 1997), and has been claimed to be the receptor mediating noradrenaline (NA) induced smooth muscle contraction in these tissues (Forray et al., 1994; Hatano et al., 1994; Marshall et al., 1995). The resulting tone is believed to contribute substantially to the urinary outflow obstruction observed in patients with BPH (Furuya et al., 1982), with the remaining obstruction being attributable to increased prostate mass. These observations have fuelled the hypothesis – yet to be supported by clinical data – that an α1A-subtype-selective antagonist may, via a selective and significant decrease in outlet resistance, lead to improved pharmacotherapy for BPH. Tamsulosin, recently approved for the treatment of BPH, is claimed to be ‘uroselective' based on a degree of α1A-subtype-selectivity, but a recent report by Blue et al. (1997a), assessing the in vitro and in vivo pharmacology of this compound, does not support this proposal.

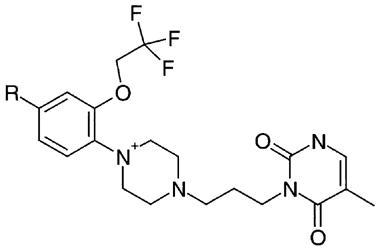

In this study we report the in vitro α1-adrenoceptor affinity profiles of two novel α1A-adrenoceptor selective antagonists, Ro 70-0004 (RS-100975; 3-(3-{4-[Fluoro-2-(2,2,2-trifluoroethoxy)-phenyl]-piperazin-1-yl}-propyl)-5-methyl-1H-pyrimidine-2,4-dione mono hydrochloride monohydrate, Figure 1) and a structurally-related compound, RS-100329 (Figure 1), in comparison with those of prazosin and tamsulosin.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of Ro 70-0004 (RS-100975: R=F) and RS-100329 (R=H).

Methods

Cell culture

Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO-K1) expressing human cloned α1A-, α1B- and α1D-adrenoceptors (see Ford et al., 1997) were cultured to confluence in tissue culture flasks (T-162) containing Ham's F-12 nutrient medium supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS), geneticin (150 μg ml−1) and penicillin/streptomycin (30 u ml−1, 30 μg ml−1) at 37°C in 7% CO2.

Radioligand binding studies

Affinity estimates (pKi) were made from competition curves (using ten concentrations of displacing agent) using intact CHO-K1 cells stably expressing human cloned α1A-, α1B- and α1D-adrenoceptors. Cells were grown as described above and harvested by incubating with Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing EDTA (30 μM) for 10 min at 37°C. Harvested cells were washed twice by centrifugation and resuspension in Ham's medium, and finally resuspended in Ham's medium at approximately 0.2×106 cells ml−1.

[3H]-Prazosin (0.3–0.4 nM; specific activity 82 Ci mmole−1) was used as the radioligand and specific binding was defined using 10 μM phentolamine. Assay tubes contained 100 μl competing compound, 100 μl [3H]-prazosin and 300 μl cell suspension. All equilibrations were carried out for 30 min at 37°C in Ham's culture medium (pH 7.4), and were terminated by vacuum filtration through glass fibre filters. Bound radioactivity was determined using liquid scintillation spectroscopy. Concentrations of competing agent producing 50% reduction of specific [3H]-prazosin binding (IC50) were calculated using non-linear iterative curve-fitting methodologies (Kaleidagraph, Synergy Software), and affinity estimates (pKi) were estimated according to Cheng & Prusoff (1973). Estimates of pKD were made by saturation analysis using 10–12 concentrations of [3H]-prazosin (1 pM–3 nM).

[3H]-Inositol phosphates accumulation

The method used was a modification of well-established procedures (Brown et al., 1984). Cells were washed with PBS and incubated overnight in 15 ml inositol-free Ham's F-12 medium containing 10% dialyzed FBS and 25 μCi [3H]-myo-inositol. Following this, the medium was aspirated and the cells washed with PBS to remove unincorporated [3H]-myo-inositol. PBS containing EDTA (30 μM for 5–10 min at 37°C) was used to dissociate cells from the flask. The cells were washed three times by centrifugation (5 min at 500×g, 37°C) and resuspension in PBS and were finally resuspended in inositol-free Ham's medium at approximately 5×106 cells ml−1.

Reactions were performed in triplicate with a final reaction volume of 300 μl. Two-hundred and forty microlitres of cell suspension was added to 30 μl antagonist or vehicle and incubated at 37°C for 20 min. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 30 μl agonist or vehicle, containing LiCl (final concentration 10 mM). Tubes were then gently mixed and placed in a 37°C bath for 10 min. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 50 μl ice-cold perchloric acid (20%), and the tubes placed on ice for 20 min. Samples were then neutralized with 160 μl 1 M KOH, vortex-mixed and centrifuged at 1000×g at 4°C for 10 min. Samples were then gently diluted with the addition of 2 ml Tris-HCl (50 mM, pH 7.5) and decanted onto disposable columns containing 1 ml Dowex AG 1X8, chloride form (1 : 1, w v−1) slurry which had been washed with 5 ml distilled H2O. Columns were then washed with 20 ml distilled H2O and the eluate discarded. [3H]-Inositol phosphates ([3H]-InsPs) were eluted with 3 ml HCl (1 M) into scintillation vials containing 15 ml Ready-Safe liquid scintillation cocktail. Accumulated [3H]-InsPs were measured by liquid scintillation spectroscopy. Iterative nonlinear curve-fitting methods using Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software) were used to fit data to the general logistic functions in order to determine EC50 or IC50 values, maxima and Hill slopes for each curve. Affinity values of test substances (pKB were calculated according to Leff & Dougall (1993), such that KB=IC50/((2+([A]/EC50)nH)1/nH−1).

In vitro tissue bath studies

Tissue bath studies were conducted at 37°C in 10 ml organ baths and used Krebs' buffer (mM: Na+ 143.5, K+ 6.0, Ca2+ 2.5, Mg2+ 1.2, Cl− 126, HCO3− 25, H2PO4− 1.2, SO42− 1.2), pH 7.4, gassed with 95% O2, 5% CO2, and supplemented with cocaine (30 μM), corticosterone (30 μM), propranolol (1 μM), idazoxan (0.3 μM), ascorbate (100 μM) and nitrendipine (1 μM: rat aorta only, see Blue et al., 1995) to ensure equilibrium conditions and α1-adrenoceptor isolation.

Human lower urinary tract tissues (LUT) were obtained from patients undergoing transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). Samples were kept in cold Krebs' solution until use in functional studies, which were performed later the same day or early the following day. Human renal artery sections (3 mm×6 mm) were obtained from a transplant donor bank, and were usually received within 24–36 h of removal. Rabbit bladder neck strips (2 mm×6 mm) were from male New Zealand White rabbits (2.5–3.5 kg) and rat aortic rings (2 mm width) were from male Sprague-Dawley rats (350–500 g), both euthanized with carbon dioxide. Vascular tissues were endothelium-denuded prior to study.

Tissues were mounted under 0.5 g (human LUT, renal artery) or 1.0 g (rabbit bladder neck, rat aorta) resting tension and allowed to equilibrate for at least 1 h. Cumulative concentration-response curves to NA were constructed in the absence and presence (following a 1 h equilibration) of various concentrations of antagonist. Responses were measured as changes in isometric tension. Iterative curve fitting (Kaleidagraph, Synergy Software) was used to determine EC50 values for the agonist in the absence and presence of various concentrations of each antagonist. Schild plots (Arunlakshana & Schild, 1959) were constructed in order to estimate antagonist affinity estimates.

Materials

Ham's F-12 nutrient media, Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline, geneticin (G418), foetal bovine serum (qualified and dialyzed), penicillin/streptomycin and versene (EDTA) were obtained from Gibco (Gaithersburg, MD, U.S.A.). Myo-[2-3H]-Inositol (10–20 Ci mmol−1) and [3H]-prazosin (82 Ci mmol−1) were obtained from Amersham (Arlington Heights, IL, U.S.A.). Disposable plastic columns (CC-09-M) were obtained from E & K Scientific Products (Saratoga, CA, U.S.A.). Prazosin was obtained from Research Biochemicals International (Natick, MA, U.S.A.). Acidic alumina (activity grade 1, Brockmann) was purchased from ICN Biomedicals GmbH (Eschwege, Geramany). NA and bulk chemicals and reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). All other compounds were synthesized in the Department of Medicinal Chemistry, Neurobiology Business Unit, Roche Bioscience (Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.). Ready-Safe liquid scintillation cocktail was purchased from Baxter Scientific (McGraw Park, IL, U.S.A.). Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO-K1) expressing human α1A-, α1B- and α1D-adrenoceptors were prepared by Dr David Chang, Center for Biological Research, Neurobiology Business Unit, Roche Bioscience (Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.).

Results

Radioligand binding studies

Saturation studies demonstrated high-affinity specific (>90%) binding of [3H]-prazosin to whole CHO-K1 cells expressing human cloned α1A-, α1B- and α1D-adrenoceptors, yielding affinity estimates (pKD, mean±s.e.mean, n⩾3) of 9.12± 0.07, 10.08±0.10 and 9.51±0.11, respectively. Estimated Bmax values were 1.64±0.20, 1.22±0.13 and 1.17±0.05 pmoles mg protein−1 respectively.

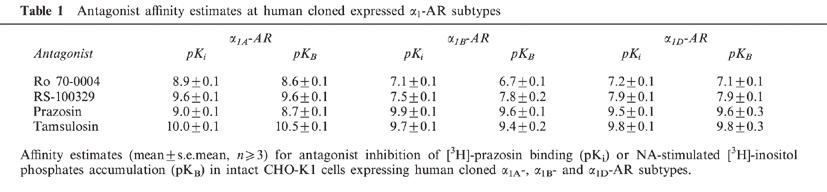

In competition studies Ro 70-0004, RS-100329, prazosin and tamsulosin all competed to the same extent for [3H]-prazosin binding: calculated affinity estimates (pKi) are shown in Table 1. Prazosin and tamsulosin demonstrated limited α1-AR subtype selectivity (<10 fold), whereas significant selectivities for the α1A- over the α1B- and α1D-AR subtypes were evident for Ro 70-0004 (60 and 50 fold respectively) and RS-100329 (126 and 50 fold respectively).

Table 1.

Antagonist affinity estimates at human cloned expressed α1-AR subtypes

Radioligand binding studies were also used to determine the affinity of Ro 70-0004 at more than 30 other neurotransmitter receptors (data not shown). Those receptors where the affinity (pKi) of Ro 70-0004 was found to be 7.0 or greater were: α2B-adrenoceptors (pKi 7.0: rat kidney), human recombinant D2L receptors (pKi 7.2), human recombinant D3 receptors (pKi 7.7) and 5-HT2A receptors (pKi 7.4: rat cortex).

[3H]-Inositol phosphates accumulation

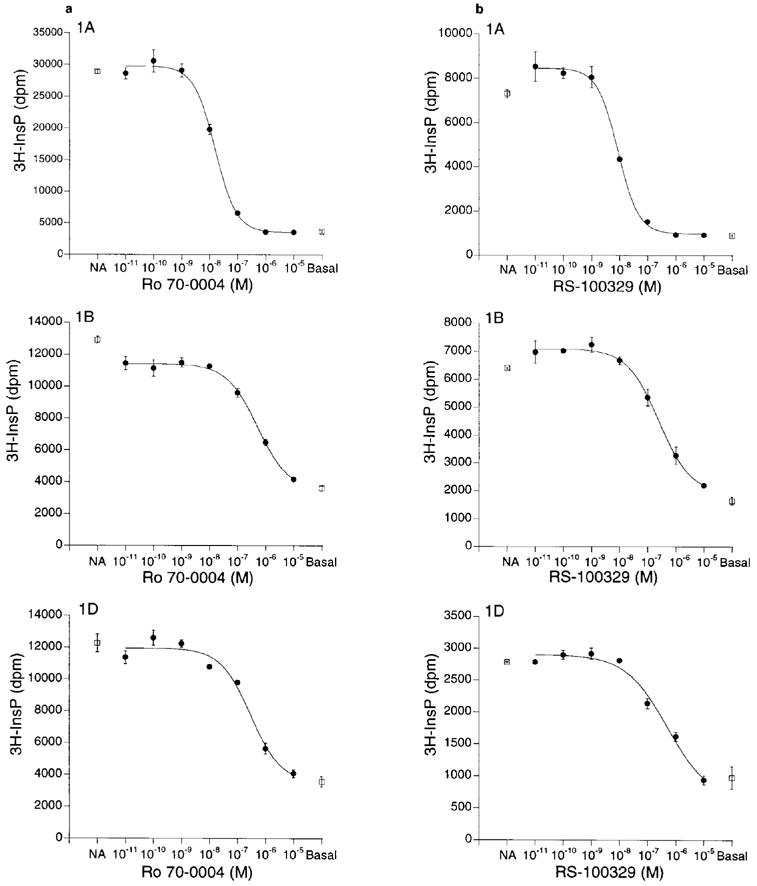

Accumulation of [3H]-inositol phosphates in CHO-K1 cells expressing human cloned α1A-, α1B- and α1D-adrenoceptors was stimulated by NA (approximately 10, 4 and 4 fold over basal) in a concentration-dependent manner, with respective pEC50 values of 6.6±0.1, 6.5±0.1 and 7.7±0.1 (mean±s.e.mean, n⩾3). Pre-incubation of cells with test antagonists inhibited the stimulation by NA (2 μM for α1A-, α1B-adrenoceptors, 0.2 μM for α1D-adrenoceptors) in a concentration-dependent manner. Resultant affinity estimates (pKB) are shown in Table 1. Note that for tamsulosin, a NA concentration of 100 μM was used to stimulate inositol phosphates accumulation (α1A-adrenoceptors only). The rationale for this is discussed in Ford et al. (1997): briefly, a higher concentration of agonist was required in order to compensate for the significant loss of tamsulosin which occurred at low concentrations of the antagonist. Under these conditions none of the antagonists tested produced inhibition curves with slopes significantly different from unity.

Prazosin showed some selectivity for the α1B- and α1D-AR subtypes over the α1A-AR subtype, whereas tamsulosin showed approximately 10 fold selectivity for the α1A-AR subtype over the α1B-, but not the α1D-AR subtype. Ro 70-0004 (Figure 2a) was 30 and 80 fold selective for the α1A-subtype over the α1B- and α1D-subtypes respectively, and RS-100329 (Figure 2b) also showed significant α1A-adrenoceptor selectivity (60 and 50 fold respectively).

Figure 2.

Antagonism by (a) Ro 70-0004 and (b) RS-100329 of NA-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphates accumulation in CHO-K1 cells expressing human recombinant α1A-, α1B- and α1D-adrenoceptor subtypes. Cells were stimulated with either 2 μM (α1A- and α1B-AR subtypes) or 0.2 μM (α1D-AR) NA (‘NA'). ‘Basal': no NA added. Data are means±s.e.mean of triplicate determinations in single representative experiments.

In vitro tissue bath studies

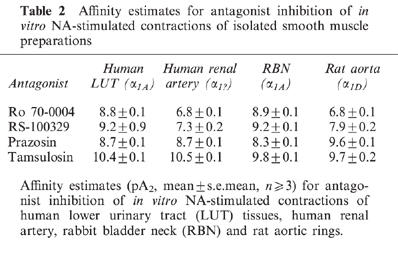

In all tissues assayed, NA caused concentration-dependent contractions which were well maintained, allowing construction of cumulative concentration-response curves. Affinity estimates calculated for the four antagonists studied are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Affinity estimates for antagonist inhibition of in vitro NA-stimulated contractions of isolated smooth muscle preparations

In human LUT tissues, contractions to NA were antagonized in a surmountable and concentration-dependent manner by Ro 70-0004, RS-100329 and prazosin with similar affinity (pA2 ∼9): tamsulosin was approximately 10 fold more potent (Table 2). Figure 3 shows the antagonism of the prostatic smooth muscle response by various concentrations of Ro 70-0004 and the resultant Schild plot. The data show a small decrease in the maximum response obtained to NA in the presence of Ro 70-0004: however, the unity slope of the Schild plot is consistent with competitive antagonism at an homogeneous population of receptors. Affinity estimates from rabbit bladder neck studies were similar to those obtained using human lower urinary tract tissues (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Antagonism of NA-induced contractions of human isolated lower urinary tract tissues in vitro by various concentrations of Ro 70-0004. Inset: resultant Schild plot. Data are means±s.e.mean of at least six determinations.

In contrast, both Ro 70-0004 and RS-100329 were approximately 100 fold weaker in antagonizing the contractile response to NA in human renal artery. The affinities of prazosin and tamsulosin did not differ from those observed in studies using human LUT tissues (Table 2). In studies using rat aortic rings, Ro 70-0004, RS-100329 and tamsulosin antagonized contractile responses to NA with affinities close to those observed for human renal artery. Prazosin however, was approximately 10 fold more potent in rat aorta when compared to human renal artery.

Discussion

The present study has compared the α1-AR subtype affinities of two novel subtype-selective antagonists, Ro 70-0004 and RS-100329, with those of prazosin and tamsulosin, two compounds currently used in the symptomatic treatment of BPH. In addition to the use of human recombinant α1-adrenoceptor subtypes, studies were also performed on native α1-adrenoceptors in LUT and vascular tissues of animals and man.

In CHO-K1 cells expressing the human α1A-, α1B- and α1D-adrenoceptor subtypes, both Ro 70-0004 and RS-100329 showed high affinity and clear selectivity (in excess of 50 fold) for the α1A-subtype over the α1B- and α1D-subtypes in intact cell radioligand binding studies using [3H]-prazosin. Functional studies (antagonism of NA-stimulated [3H]-inositol phosphates accumulation) in the same cells produced similar results. In binding studies tamsulosin showed no subtype selectivity, whereas in functional studies the compound was slightly (approximately 10 fold) selective for the α1A-subtype over the α1B- but not the α1D-adrenoceptor subtype. In both binding and functional studies prazosin showed lower, suprananomolar affinity at the α1A-adrenoceptor than at the other two subtypes (reminiscent of the so-called ‘α1L-adrenoceptor'). In a recent study Williams et al. (1996) reported that in radioligand binding studies performed under suitable assay conditions (whole cells, 37°C), the pharmacological profile of the human recombinant α1A-adrenoceptor expressed in CHO-K1 cells more closely resembled that of the proposed ‘α1L'-adrenoceptor (see Ford et al., 1997) than that found in membrane homogenates (at 20°C). The latter resembled the classically-defined α1A-adrenoceptor. Specifically, with whole cells at 37°C some antagonists, including prazosin, WB4101 and RS-17053 but not tamsulosin or indoramin showed significantly lower affinities than those measured in membranes and also reported in ‘classical' α1A-adrenoceptor preparations. This ‘αIL-like' pharmacological profile for the recombinant receptor is not confined to binding studies, since it is also observed in functional studies measuring antagonism of NA-induced [3H]-inositol phosphates accumulation (Ford et al., 1997), [3H]-cAMP accumulation (Gever et al., 1997) or intracellular Ca2+ elevation (unpublished observations) in the same cells. Although the ‘classical' α1A-adrenoceptor was first described in rat tissues (Morrow & Creese, 1986), studies have shown that recombinant α1A-adrenoceptors from rat, rabbit and man exhibit similar pharmacological profiles (‘αIL-like') in functional studies (Daniels et al., 1996), so species variation does not seem to account for α1A/αIL-AR differences. The mechanisms underlying the different pharmacological profiles exhibited by the α1A-adrenoceptor are yet to be determined. Although the possibility remains that further α1-adrenoceptor subtypes may be cloned, to date there is no compelling evidence to suggest that a novel subtype is required to account for the pharmacological observations of the α1L-AR.

Notwithstanding the above, one of the proposed therapeutic advantages of an α1A-adrenoceptor-selective antagonist is a selective action on lower urinary tract tissues and minimal cardiovascular side effects. In accordance with their high affinities at recombinant α1A-adrenoceptors, both Ro 70-0004 and RS-100329 showed nanomolar affinities in functional studies assessing their ability to antagonize NA-induced contractions of human lower urinary tract tissues and rabbit bladder neck in vitro. The latter tissue contracts in response to α1-adrenoceptor agonism via a receptor with a pharmacological profile which correlates closely with that observed in human LUT tissues (Kava et al., 1998). In contrast to their affinities in LUT tissues, Ro 70-0004 and RS-100329 (but not prazosin or tamsulosin) were found to be significantly less potent when tested as antagonists of NA-induced contractions in human renal artery or rat aorta. The α1-adrenoceptor subtype(s) mediating contraction of human renal artery to NA are not yet determined, but those mediating contraction of rat aorta appear to be predominantly of the α1D-subtype (Buckner et al., 1996; Saussy et al., 1996; but see also Van der Graaf et al., 1996). The results of the present study would support this hypothesis: affinities from functional studies using rat aorta closely match those from binding and functional studies using the cloned expressed α1D-adrenoceptor.

Clearly, pharmacological data from in vitro studies using isolated vascular tissues cannot necessarily be extrapolated to exclude significant in vivo cardiovascular effects of α1A-adrenoceptor-selective antagonists. The extent to which larger conductance vessels, rather than smaller arterioles, contribute to total peripheral resistance is thought to be minor. At least in rat, in vitro pressor responses to α1-adrenoceptor agonists in perfused mesentery (Williams & Clarke, 1995) and perfused kidney (Blue et al., 1995) both seem to be mediated by α1A-adrenoceptors. To address this question Blue et al. (1997b) have described a ‘reflex-compromised' model for the assessment of the hypotensive potential of α1-adrenoceptor antagonists in conscious rats. In this model, rats are pretreated with a β1-adrenoceptor antagonist, an AT1 angiotensin receptor antagonist, and a non-subtype-selective α2-adrenoceptor antagonist in order to maximize the hypotensive potential of α1-adrenoceptor antagonism, by blunting compensatory cardiovascular reflexes. In this model, Ro 70-0004 was observed to be approximately 200 fold less potent than prazosin at lowering resting blood pressure (Blue et al., 1997b). In addition, Ro 70-0004 was found to be approximately 100 fold less potent than prazosin at producing postural hypotension during head-up tilt (Blue et al., 1996). Similar results were seen in tilt studies using conscious dogs. Other in vivo studies with Ro 70-0004 also support a selective action on LUT tissues. Blue et al. (1996) report that in anaesthetized mongrel dogs, Ro 70-0004 was 76 fold more potent at inhibiting hypogastric nerve stimulation-induced rises in intraurethral pressure versus phenylephrine-induced rises in diastolic blood pressure. In the same study, neither prazosin nor tamsulosin – despite its claimed α1A-selectivity – distinguished between urethral and diastolic blood pressure responses. Similar results with tamsulosin have also been observed by other authors (Kenny et al., 1996). In vivo studies performed using RS-100329 in rats and dogs (unpublished data) confirmed selectivity properties similar to those of Ro 70-0004, but with greater potency, commensurate with its higher affinity for the α1A-AR. In studies with Rec 15/2739 (SB 216469), which is also selective for the α1A-subtype, the compound was also reported to be ‘uroselective' in dogs (Testa et al., 1997). Thus, there is significant data supporting the hypothesis that in vitro selectivity for the α1A-adrenoceptor can translate into a selective action on LUT tissues in vivo.

In summary, the present study has shown Ro 70-0004, and a structurally-related compound RS-100329, to be high affinity antagonists at the α1A-adrenoceptor, with considerable selectivity over the α1B- and α1D-subtypes. The compounds potently inhibit in vitro and in vivo α1-adrenoceptor-mediated contractions of lower urinary tract tissues and appear to exhibit only weak cardiovascular effects when compared to standard non-subtype-selective α1-adrenoceptor antagonists. The clinical utility of Ro 70-0004 in the symptomatic treatment of BPH is currently being assessed.

Abbreviations

- AR

adrenoceptors

- BPH

benign prostatic hyperplasia

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- HRA

human renal artery

- LUT

lower urinary tract

- NA

noradrenaline

- RA

rat aorta

- RBN

rabbit bladder neck

References

- ARUNLAKSHANA O., SCHILD H.O. Some quantitative uses of drug antagonists. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1959;14:48–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1959.tb00928.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLUE D.R., BONHAUS D.W., FORD A.P.D.W., PFISTER J.R., SHARIF N.A., SHIEH I.A., VIMONT R.L., WILLIAMS T.J., CLARKE D.E. Functional evidence equating the pharmacologically-defined α1A- and α1C-adrenoceptors: studies in the isolated perfused kidney of rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:283–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15875.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLUE D.R., DANIELS D.V., FORD A.P.D.W., WILLIAMS T.J., EGLEN R.E., CLARKE D.E. Pharmacological assessment of the α1-adrenoceptor (α1-AR) antagonist tamsulosin. J. Urol. 1997a;157 4:190. [Google Scholar]

- BLUE D.R., FORD A.P.D.W., MORGANS D.J., PADILLA F., CLARKE D.E. Preclinical pharmacology of a novel α1A/α1L-adrenoceptor antagonist, RS-100975. Neurourol. Urodynam. 1996;15:345. [Google Scholar]

- BLUE D.R., FORD A.P.D.W., MORGANS D.J., WILLIAMS T.J., ZHU Q.-M., CLARKE D.E. The conscious ‘reflex-compromised' rat: a model for evaluating the hypotensive potencies of the α1-adrenoceptor antagonists prazosin, tamsulosin and Ro 70-0004. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997b;120:107P. [Google Scholar]

- BROWN E., KENDALL D.A., NAHORSKI S.R. Inositol phospholipid hydrolysis in rat cerebral cortical slices. I. Receptor characterisation. J. Neurochem. 1984;42:1379. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb02798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUCKNER S.A., OHEIM K.W., MORSE P.A., KNEPPER S.M., HANCOCK A.A. α1-Adrenoceptor-induced contractility in rat aorta is mediated by the α1D subtype. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996;297:241–248. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00755-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUZELIN J.M., HEBERT M., BLONDIN P., THE PRAZALF GROUP Alpha-blocking treatment with alfuzosin in symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: comparative study with prazosin. Br. J. Urol. 1993;72:922–927. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb16298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAINE M., PERLBERG S., MERETYK S. A placebo-controlled double-blind study of the effect of phenoxybenzamine in benign prostatic obstruction. Br. J. Urol. 1978;50:551–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1978.tb06210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAPPLE C.R., STOTT M., ABRAMS P.H., CHRISTMAS T.J., MILROY E.J.G. A 12-week placebo-controlled double blind study of prazosin in the treatment of prostatic obstruction due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Br. J. Urol. 1992;70:285–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1992.tb15733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENG Y.-C., PRUSOFF W.H. Relationship between the inhibitor constant (Ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 percent inhibition of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DANIELS D.V., GEVER J.R., MELOY T.D., CHANG D.J., KOSAKA A.H., CLARKE D.E., FORD A.P.D.W. Functional pharmacological characteristics of human, rat, and rabbit cloned α1A-adrenoceptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;119:360P. [Google Scholar]

- FAURE C., PIMOULE C., VALLANCIEN G., LANGER S.Z., GRAHAM D. Identification of α1-adrenoceptor subtypes present in the human prostate. Life Sci. 1994;54:1595–1605. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLAVAHAN N.A., VANHOUTTE P.M. α-Adrenoceptor Classification in Vascular Smooth Muscle. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1986;7:347–349. [Google Scholar]

- FORD A.P.D.W., ARREDONDO N.F., BLUE D.R., BONHAUS D.W., JASPER J., KAVA M.S., LESNICK J., PFISTER J.R., SHIEH I.A., VIMONT R.L., WILLIAMS T.J., MCNEAL J.E., STAMEY T.A., CLARKE D.E. RS-17053 (N-[2-(2-cyclopropylmethoxyphenoxy)ethyl] - 5 - chloro-a,a-dimethyl-1H-indole-3-ethanamine hydrochloride), a selective α1A-adrenoceptor antagonist, displays low affinity for functional α1-adrenoceptors in human prostate: implications for adrenoceptor classification. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;49:209–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORD A.P.D.W., BLUE D.R., WILLIAMS T.J., CLARKE D.E. α1-Adrenoceptor Classification: Sharpening Occam's Razor. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1994;15:167–170. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORD A.P.D.W., DANIELS D.V., CHANG D.J., GEVER J.R., JASPER J.R., LESNICK J.D., CLARKE D.E. Pharmacological pleiotropism of the human recombinant α1A-adrenoceptor: implications for α1-adrenoceptor classification. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121:1127–1135. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORRAY C., BARD J.A., WETZEL J.M., CHIU G., SHAPIRO E., TANG R., LEPOR H., HARTIG P.R., WEINSHANK R.L., BRANCHEK T.A., GLUCHOWSKI C. The α1-Adrenoceptor that mediates smooth muscle contraction in human prostate has the pharmacological properties of the cloned human α1C-adrenoceptor subtype. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:703–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FURUYA S., KUMAMOTO Y., YOKOYAMA E., TSUKAMOTO T., IZUMI T., ABIKO Y. Alpha-adrenergic activity and urethral pressure in prostatic zone in benign prostatic hypertrophy. J. Urol. 1982;128:836–839. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)53216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEVER J.R., DANIELS D.V., MELOY T.D., YAMANISHI S.S., KOSAKA A.H., CHANG D.J., CLARKE D.E., EGLEN R.M., FORD A.P.D.W. Effector-independent antagonist affinity profile of human cloned α1A-adrenoceptor expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO-K1) Pharmacologist. 1997;39:125. [Google Scholar]

- HATANO A., TAKAHASHI H., TAMAKI M., KOMEYAMA T., KOIZUMI T., TAKEDA M. Pharmacological evidence of distinct α1-adrenoceptor subtypes mediating the contraction of human prostatic urethra and peripheral artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;113:723–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17053.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEDLUND H., ANDERSSON K.-E., EK A. Effects of prazosin in patients with benign prostatic obstruction. Br. J. Urol. 1983;130:275–278. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)51106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIEBLE J.P., BYLUND D., CLARKE D.E., EIKENBURG D.C., LANGER S.Z., LEFKOWITZ R.J., MINNEMAN K.P., RUFFOLO R.J. International Union of Pharmacology X. Recommendation for Nomenclature of α1-Adrenoceptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 1995;47:267–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAVA M.S., BLUE D.R., VIMONT R.L., CLARKE D.E., FORD A.P.D.W. α1L-Adrenoceptor mediation of smooth muscle contraction in rabbit bladder neck: a model for lower urinary tract tissues of man. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123:1359–1366. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KENNY B.A., MILLER A.M., WILLIAMSON I.J.R., O'CONNELL J., CHALMERS D.H., NAYLOR A.M. Evaluation of the pharmacological selectivity profile of α1-adrenoceptor antagonists at prostatic α1 adrenoceptors: binding, functional and in vivo studies. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:871–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15480.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEFF P., DOUGALL I.G. Further concerns over Cheng-Prusoff analysis. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1993;141:110–112. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEPOR H. Long-term efficacy and safety of terazosin in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 1995;45:406–413. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARSHALL I., BURT R.P., CHAPPLE C.R. Noradrenaline contractions of human prostate by α1A-(α1C-) adrenoceptor subtype. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:781–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORROW A.L., CREESE I. Characterisation of α1-adrenoceptor subtypes in rat brain: a reevaluation of [3H]WB4101 and [3H]prazosin binding. Mol. Pharmacol. 1986;29:321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURAMATSU I. α-Adrenoceptors. Tokyo: Excerpta Medica, Ltd; 1992. A pharmacological perspective of α1-adrenoceptors: subclassification and functional aspects; pp. 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- PRICE D., SCHWINN D.A., LOMASNEY J.W., ALLEN L.F., CARON M.G., LEFKOWITZ R.J. Identification, quantification and localisation of mRNA for three distinct α1-adrenergic receptor subtypes in human prostate. J. Urol. 1993;150:546–551. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35544-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAUSSY D.L., GOETZ A.S., QUEEN K.L., KING H.K., LUTZ M.W., RIMELE T.J. Structure activity relationships of a series of buspirone analogs at alpha-1 adrenoceptors: further evidence that rat aorta alpha-1 adrenoceptors are of the alpha-1D subtype. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;278:136–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANIGUCHI N., UKAI Y., TANAKA T., YANO J., KIMURA K., MORIYAMA N., KAWABE K. Identification of alpha 1-adrenoceptor subtypes in human prostatic urethra. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1997;355:412–416. doi: 10.1007/pl00004962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TESTA R., GUARNERI L., ANGELICO P., POGGESI E., TADDEI C., SIRONI G., COLOMBO D., SULPIZIO A.C., NASELSKY D.P., HIEBLE J.P., LEONARDI A. Pharmacological characterisation of the uroselective alpha-1 antagonist Rec 15/2739 (SB 216469): Role of the alpha-1L adrenoceptor in tissue selectivity, Part II. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 1997;281:1284–1293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN DER GRAAF P.H., SHANKLEY N.P., BLACK J.W. Analysis of the activity of α1-adrenoceptor antagonists in rat aorta. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:299–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS T.J., CLARKE D.E. Characterization of α1-Adrenoceptors mediating vasoconstriction to noradrenaline and nerve stimulation in the isolated perfused mesentery of rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:531–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS T.J., CLARKE D.E., FORD A.P.D.W. Whole cell radioligand binding assay reveals α1L-adrenoceptor (AR) antagonist profile for the human cloned α1A-AR in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;119:359P. [Google Scholar]