Abstract

In the rat corpus cavernosum (CC), the distribution of immunoreactivity for neuronal and endothelial NO synthase (nNOS and eNOS), and the pattern of NOS-immunoreactive (-IR) nerves in relation to some other nerve populations, were investigated. Cholinergic nerves were specifically immunolabelled with antibodies to the vesicular acetylcholine transporter protein (VAChT).

In the smooth muscle septa surrounding the cavernous spaces, and around the central and helicine arteries, the numbers of PGP- and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-IR terminals were large, whereas neuropeptide Y (NPY)-, VAChT-, nNOS-, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)-IR terminals were found in few to moderate numbers.

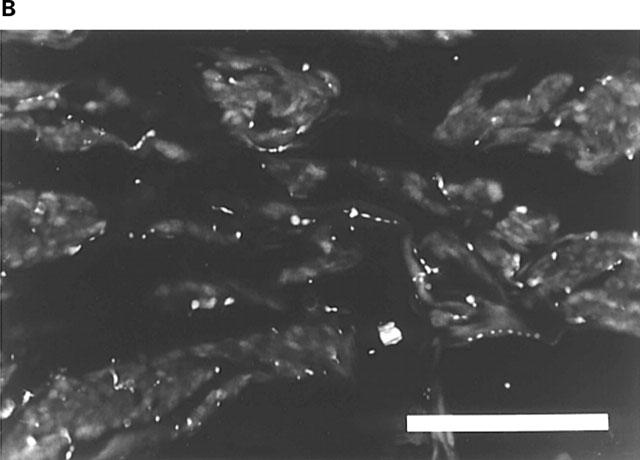

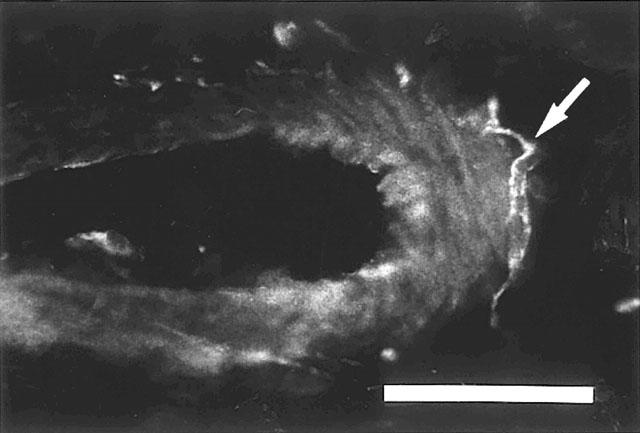

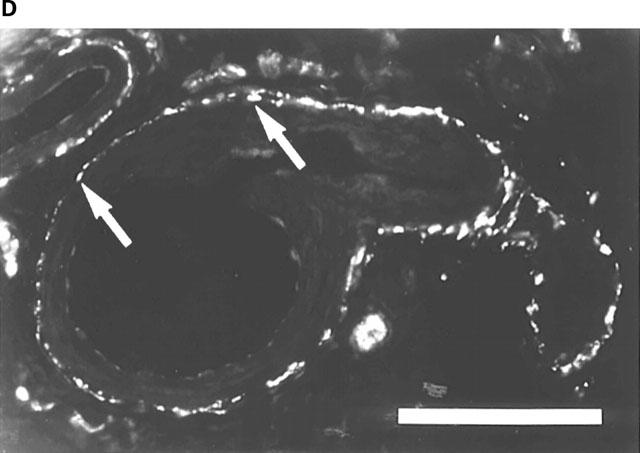

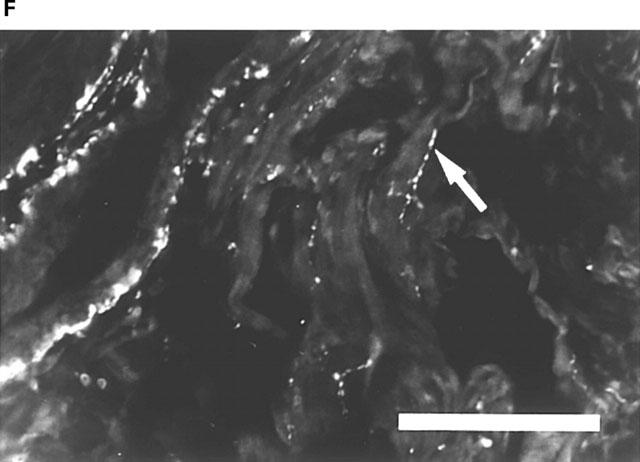

Double immunolabelling revealed that VAChT- and nNOS-IR terminals, VAChT- and VIP-IR terminals, nNOS-IR and VIP-IR terminals, and TH- and NPY-IR terminals showed coinciding profiles, and co-existence was verified by confocal laser scanning microscopy. TH immunoreactivity was not found in VAChT-, nNOS-, or VIP-IR nerve fibres or terminals.

An isolated strip preparation of the rat CC was developed, and characterized. In this preparation, cumulative addition of NO to noradrenaline (NA)-contracted strips, produced concentration-dependent, rapid, and almost complete relaxations. Electrical field stimulation of endothelin-1-contracted preparations produced frequency-dependent responses: a contractile twitch followed by a fast relaxant response. After cessation of stimulation, there was a slow relaxant phase. Inhibition of NO synthesis, or blockade of guanylate cyclase, abolished the first relaxant phase, whereas the second relaxation was unaffected.

The results suggest that in the rat CC, nNOS, VAChT-, and VIP-immunoreactivities can be found in the same parasympathetic cholinergic neurons. Inhibitory neurotransmission involves activation of the NO-system, and the release of other, as yet unknown, transmitters.

Keywords: Penile erection, vesicular acetylcholine transporter protein, tyrosine hydroxylase, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, heme oxygenase, carbon monoxide, guanylate cyclase

Introduction

Immunoreactivity for the nitric oxide (NO)-producing enzyme, NO-synthase (NOS), has been demonstrated in nerves innervating the erectile tissue of the rat penis (Burnett et al., 1992; 1993; Alm et al., 1993; Tamura et al., 1997). As a result of activation of nerves and/or endothelium, NO, synthesized from L-arginine, is released, activates soluble guanylate cyclase, and increases the production of cyclic guanosine 3′, 5′monophosphate (cGMP; Rand & Li, 1996). Inhibition of the synthesis of NO has been demonstrated to effectively counteract electrically-induced relaxations in isolated erectile tissue, and the erectile response in several animal models has been shown to depend upon neuronally-released NO (Finberg et al., 1993; Andersson & Wagner, 1995).

NOS-immunoreactive (-IR) nerves in penile erectile tissue have been shown also to contain immunoreactivity for vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), and VIP is the most abundant peptide in the corpus cavernosum (CC) of several species. The peptide produces relaxation of isolated, contracted CC preparations, and effectively counteracts electrically induced contractions (Andersson & Wagner, 1995).

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) has been demonstrated histochemically in nerves innervating the penis (Gu et al., 1983), and these presumably cholinergic nerves have been suggested also to contain VIP (Dail et al., 1986). In ultrastructural studies of penile tissue, large VIP-IR vesicles have been shown to co-localize with small and clear, presumably acetylcholine (ACh)-containing vesicles within nerve varicosities (Steers et al., 1984). Histochemical visualization of AChE in nerves is, however, not specific for the distribution of cholinergic nerves, and attempts to develop better markers for these nerves have been made. Vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) protein is a small carrier protein, which transfers newly synthesized ACh into presynaptic vesicles, and immunohistochemical visualization of the VAChT protein has been suggested to be a unique marker for investigation of the distribution of cholinergic nerves in the peripheral and central nervous systems (Arvidsson et al., 1997).

Activation of presynaptic muscarinic receptors on adrenergic nerve terminals, with a decreased release of noradrenaline, and muscarinic receptor-mediated release of relaxant factors from the endothelium have been suggested as cholinergic functions contributing to the erectile response (Andersson & Wagner, 1995). The endothelium of rat penile arteries and veins has been shown to contain NOS immunoreactivity, and also to exhibit a positive reaction against nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate diaphorase (NADPHd; Keast, 1992; Dail et al., 1995). Although endothelium- and NO-dependent relaxations are found in cavernous tissue from different species (Andersson & Wagner, 1995), the ability of the rat sinusoidal endothelium to produce NO is disputed (Dail et al., 1995).

The rat is a commonly used model for the study of erectile events. However, there are few studies performed on isolated rat CC, and this tissue has not yet been well characterized functionally. Therefore, in the present study, an isolated preparation of the rat CC was developed, and the in vitro responses to electrical field stimulation of nerves and to agents possibly involved in erection were characterized. In the same tissue, the distribution of immunoreactivity for NOS in nerves and endothelium (d.f. Dail et al., 1995), and the innervation pattern of NOS-IR nerves in relation to adrenergic, cholinergic, and some peptide-containing nerves were investigated, as was the distribution of heme oxygenase immunoreactivity. Recently developed antibodies to VAChT (Arvidsson et al., 1997) were used for the immunocytochemical demonstration of cholinergic nerves.

Methods

Animals

Thirty-six male Sprague Dawley rats (body weight about 250 g; B & K Universal, Stockholm, Sweden) with free access to water and standard pellets were used.

Morphological studies

Chemical sympathectomy

Six rats were given two intravenous doses of a freshly prepared solution of 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA; Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO, U.S.A.) with an interval of 1 day between each injection (100 mg kg−1; dissolved in ice-cold saline containing 0.2 mg ml−1 ascorbic acid) and sacrified 1 day after the last injection.

Tissue handling

Rats were anaesthetized with ketamine (100 mg kg−1, im; Ketalar®, Park Davis, Barcelona, Spain) and xylazin (15 mg kg−1, im; Rompun®, Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany), and perfused via a cannula through the left ventricle of the heart. The rats were first perfused with 100 ml of ice-cold, calcium-free Krebs buffer (containing 0.5 g 1−1 of sodium nitrite and 10,000 IU l−1 of heparin), and then with 300 ml of an ice-cold, freshly prepared solution of 4% formaldehyde (FA) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4). The penis was removed by cutting the crura corpora cavernosa at the point of adhesion to the lower pubic bone, and the CC were then dissected free and further immersion-fixed for 4 h in the same FA solution (see above), followed by rinsing in 15% sucrose in PBS (three rinses during 48 h), and then frozen in isopentane at −40°C, and stored at −70°C. Cryostat sections were cut at a thickness of 8 μm, thaw-mounted to glass slides, and dried for about 30 min before further processing for immunocytochemistry.

Some rats were killed under a narcosis of carbon dioxide, whereupon CC tissue was rapidly dissected as described above, and frozen in isopentane at −40°C and stored at −70°C. Cryostat sections were thereupon processed for AChE histochemistry.

Immunocytochemistry

Sections were pre-incubated in PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 2 h, and then incubated for 2 days at +4°C in the presence of rabbit antisera against protein gene product 9.5 (PGP, 1 : 2000; Ultraclone, Wellow, Isle of Wight, England), or constitutive heme oxygenase (HO-2, 1 : 1000; StressGen, Victoria, Canada), or endothelial NOS (1 : 500; Santa Cruz Biotech., Heidelberg, Germany). After rinsing in PBS (three rinses during 10 min), the sections were incubated for 90 min with Texas Red-conjugated affinity purified donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (IG; 1 : 80; code 711-075-152, Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc, West Grove, PA, U.S.A.), or fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated swine anti-rabbit IG (1 : 80; Dakopatts, Stockholm, Sweden). After rinsing, the sections were mounted in PBS/glycerol with p-phenylenediamine to prevent fluorescence fading (Johnson & Nogueira Araujo, 1981).

For the simultaneous demonstration of two antigens (Wessendorf & Elde, 1985), some sections were incubated overnight with a goat antiserum to vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT, 1 : 1600; Chemicon, Malmö, Sweden), rinsed in PBS (three rinses during 10 min), and then incubated overnight in one of the following antisera raised in rabbits: neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS; 1 : 1280; Euro-Diagnostica, Malmö, Sweden), neuropeptide Y (NPY, 1 : 640, Euro-Diagnostica), tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, 1 : 200; Pel-Freez, Rogers, AR, U.S.A.), or inducible heme oxygenase (H0-1) (1 : 3000, Hsp 32, code SPA-895, StressGen, Victoria, Canada).

Some sections were incubated overnight with a rabbit VAChT antiserum (1 :2400; Euro-Diagnostica), rinsed, and then incubated overnight with guinea-pig antisera to VIP (1 : 640; Euro-Diagnostica), or calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP; 1 : 640 Euro-Diagnostica), or with a sheep antiserum to nNOS (1 : 6000; kind gift of Dr P Emson, Cambridge, England). After rinsing, the sections were incubated for 90 min with FITC-conjugated swine anti-rabbit IG (see above), rinsed, and then incubated for 90 min with Texas Red conjugated donkey anti-sheep IG (1 : 125; code 713-075-147), donkey anti-goat IG (1 : 125; code 705-076-147), or donkey anti-guinea-pig IG (1 : 125, code 706-075-148; Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc, West Grove, PA, U.S.A.).

Some sections were incubated overnight with the rabbit HO-1 or TH antisera (see above), or the guinea-pig VIP antiserum, rinsed, and then incubated overnight with the sheep nNOS antiserum. After rinsing, the sections were incubated for 90 min with FITC-conjugated goat anti-guinea-pig IG (1 : 80; Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO, U.S.A.), or swine anti-rabbit IG (1 : 80; see above), rinsed, and then incubated for 90 min with Texas Red conjugated donkey anti-sheep IG (1 : 125; see above). The sections were thereupon rinsed and mounted as described above. The Texas Red conjugated IG were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc, West Grove, PA, U.S.A.

All antisera (primary and secondary) were diluted in PBS. In control experiments, no immunoreactivity could be detected in sections incubated in the absence of the primary antisera, or with antisera absorbed with excess (100 μg ml−1) of the respective antigen (except nNOS (sheep), eNOS and TH), for which antigenic substances were not available). The respective characteristics of the rabbit and sheep nNOS and the goat VAChT antisera have previously been described (Alm et al., 1993; Herbison et al., 1996; Arvidsson et al., 1997). As cross reactions to antigens sharing similar amino acid sequences cannot be completely excluded, the structures demonstrated are referred to as HO-1-, HO-2-, nNOS-, eNOS-, PCP-TH-, NPY-, VAChT-, CGRP-, and VIP-IR (immunoreactive). The immunoreactive structures were evaluated with respect to frequency (very large, large, moderate, few, very few, absence of nerves), and to type of nerve fibres (nerve trunks, nonvaricose nerve fibres, and terminals; c.f. Lundberg et al., 1988). The term ‘coinciding profiles' has been used when, in double immunolabelling, structural details in nerve fibres (varicosities and intervaricose segments), visualised with the different fitiophores, are identical. The term ‘running closely together implies' that structures visualized with the different fluophores exhibit very similar, although not identical, structural details. The term ‘co-existing' is used for fluophores which are visualized in the same nerve structures by double filter settings or by confocal laser scanning microscopy (see below).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

To evaluate if two immunoreactivities were located in the same nerve structures, sections were analysed in a Bio-Rad MRC-1024 confocal laser scanning equipment (Bio-Rad Laboratories, U.K.) attached to a Nikon Eclipse E800 upright microscope (Nikon, Japan). The sections were scanned with a 60×(1.40) oil immersion plan apochromat lens. Sequential scanning was performed using excitation wavelengths of 488 and 568 nm from a Krypton-Argon laser. FITC immunofluorescence was detected with a 522±30 nm band pass filter and Texas Red immunofluorescence was detected with a 605±30 nm band pass filter.

Acetylcholine esterase histochemistry

Sections were processed for the copper thiocholine method of Koelle & Friedenwald (1949) as modified by Holmstedt (1957), using promethazine for inhibition of non-specific choline esterase activity (Matthews et al., 1974). The sections were incubated at +37°C for 6 h, rinsed in distilled water, counter-stained in eosin, and mounted.

Functional studies

Isometric tension measurements

For the functional experiments, the rats were sacrificed by carbon dioxide asphyxia followed by exsanguination. The penises were immediately removed, as described above, and placed in chilled Krebs solution (for composition see below). The tunica albuginea was carefully opened from its proximal extremity of the CC towards the penile shaft and the erectile tissue within the CC was microsurgically dissected free. One crural strip preparation was obtained from each corpus cavernosum. All preparations were used immediately after removal.

Silk ligatures were applied at both ends of the strip preparations (0.5×0.5×3 mm), which were then suspended between two L-formed metal prongs in thermostatically controlled organ baths (5 ml, +37°C ) containing Krebs solution aerated with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (pH 7.4). The bath fluid was routinely changed every 30 min and replaced with fresh Krebs solution, also kept at +37°C. Isometric tension was recorded by means of a Grass Instruments FT03C force-transducer connected to a Grass 71) polygraph (Grass Instruments Co, Quincy, MA, U.S.A.).

Electrical field stimulation

Electrical field stimulation (EFS) was performed with two platinum electrodes, placed in parallel to the sides of the strips in the organ baths. The nerves of the preparations were stimulated by means of a Grass S 48 stimulator, delivering single square-wave pulses at supramaximum voltage with a duration of 0.5 ms. The polarity was changed after each pulse by means of a polarity-changing unit. The train duration was 5 s and the train interval 120 s.

Experimental procedure

During an equilibration period of 45 min, tension was adjusted until a mean stable tension of 1.2±0.1 mN (n=37, N=24) was obtained. In order to verify the contractile ability of the preparations, a K+ solution (124 mM) was added to the organ baths at the end of the equilibration period. The mean contractile response amounted to 3.6±0.3 mN (n=37, N=24). Concentration-response curves for 1-noradrenaline (NA; Figure 1) and endothelin-1 (ET) were performed. The agonist concentrations used (10−5 M for NA, and 3×10−8 M for ET) corresponded to their approximate EC50 values. The effects of NO, CO, VIP and carbachol were investigated in NA-contracted preparations.

Figure 1.

Rat corpus cavernosum. (A) PGP-IR terminals accompanying smooth muscle bundles. FITC-immunofluorescence. (B) Reduced number of PGP-IR terminals following chemical sympathectomy. FITC-immunofluorescence. (C) AChE-positive terminals along smooth muscle bundles and forming plexuses around branches of central arteries. Bars=100 μm.

Frequency-response relationships were investigated at supramaximum voltage in all preparations stimulated electrically, and the effects of prazosin, VIP, NPY, and CGRP on electrically-induced excitatory responses were studied. A preparation was regarded as stable when the amplitude of three consecutive electrically-induced contractions did not differ by more than 5%. The investigated drugs were then added cumulatively. The degree of inhibition was expressed as a percentage of the contraction elicited prior to the addition of the lowest concentration of the drugs.

In order to obtain inhibitory responses by transmural stimulation of nerves, preparations were first pretreated with prazosin (10−6 M; 15 min), contracted with ET (3×10−8 M), and then exposed to EFS. The degree of relaxation was expressed as percentage of the ET-induced contraction. Some preparations were pretreated for 30 min with the NO synthesis inhibitor, NG-nitro-L-arginine (L-NNA; 10−4 M) or the guanylate cyclase inhibitor, ODQ (10−6 M). Effects of EFS were then investigated as described above.

Drugs and solutions

A Krebs solution of the following composition was used (mM): NaCI 119, KCI 4.6, CaC12 1.5, MgC12 1.2, NaHCO3 15, NaH2PO4 1.2, glucose 5.5. A high K+ solution (124 mM) was used, in which the NaCI in the normal Krebs solution was replaced by equimolar amounts of KCI. The following drugs were used: l-noradrenaline hydrochloride (Aldrich-Chemie GmbH & Co, Steinheim, Germany), carbamylcholine chloride (carbachol), prazosin hydrochloride, VIP, NPY, CGRP, and L-NNA (Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO, U.S.A.), 1H-[1,2,4]-oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ; Tocris Cookson Ltd, Bristol, U.K.), tetrodotoxin (TTX, Latoxan, Rosans, France), ET-1 (Peninsula, St Helens, U.K.). Stock solutions were prepared and then stored at −70°C and subsequent dilutions of the drugs were made with 0.9% NaC1 (NA with ascorbic acid added as an antioxidant). NO and CO were freshly prepared at each experiment. Air-tight glass-beakers containing 20 ml of distilled water were deoxygenated during 1 h with helium gas. The beakers were then aerated with medical NO or CO gas (purity>99.5%) for 15 min until saturated solutions were obtained (NO; 3×10−3 M, CO; 10−3M).

Calculations

Student's paired or unpaired two-tailed t-tests were used for statistical comparison of two means. A probability of P<0.05 was accepted as significant. When appropriate, results are given as mean values±standard error of the mean (s.e.mean). Small n denotes the number of strip preparations, and capital N denotes the number of individuals. All statistical calculations are based on N.

Results

Immunocytochemistry, confocal microscopy and acetylcholine esterase histochemistry

In the trabecular tissue surrounding the central artery and its branches, the helicine arteries, there were coarse nerve trunks displaying PGP-, nNOS-, TH-, and HO-1 immunoreactivities, the nNOS- and HO-1-IR fibres within the trunks generally showing similar, but not identical profiles. In some nerve trunks, single CGRP-IR fibres could be observed. nNOS- and TH-immunoreactivities within coarse nerve trunks were found in separate nerve fibres. No HO-2-, NPY-, VAChT-, or VIP-IR nerve trunks were found.

In the smooth muscle septa surrounding the cavernous spaces, the numbers of PGP- (Figure 1) and TH-IR terminals were very large. In comparison, the numbers of NPY-, VAChT-, NOS-, and VIP-IR terminals were few to moderate, whereas the number of AChE positive terminals (Figure 1) were moderate to large, and only very few CGRP-IR terminals could be observed. No nerve fibres displaying HO-1 or HO-2-immunoreactivity were found.

The central and the helicine arteries were accompanied by smooth-contoured PGP-, and HO-1-IR nerve fibres (Figure 2), and PCP-, nNOS-, NPY-, TH-, VAChT-, VIP-IR and AChE-positive terminals, which formed net-like plexuses in the adventitial layer up to the border of the thick media. Plexuses consisting of PGP-, nNOS-IR, and AChE-positive terminals were more dense than those displaying VAChT-, VIP- and NPY-immunoreactivities, the densities of the latter being appreciably similar. In addition, single CGRP-IR terminals were detected, whereas no HO-2-IR nerve structures were observed.

Figure 2.

Rat corpus cavemosum. Branch of a central artery with HO-1-IR nerve fibres (arrow) at the outer margins of the vessel. Texas Red-immunofluorescence. Bar=50 μm.

Double immunolabelling revealed that VAChT- and nNOS-IR terminals, and VAChT- and VIP-IR terminals, and nNOS- and VIP-IR terminals generally showed coinciding profiles (Figure 3). With confocal sections, VAChT- and nNOS-, and VAChT- and VIP-, and nNOS- and VIP-immunoreactivities were found to co-exist in the majority of nerve fibres and terminals (Figure 5). VAChT- and TH-, VAChT- and NPY-, and nNOS- and TH-IR terminals were running closely, together (Figure 4), but not in the same nerve structures (Figure 5). VAChT- and CGRP-IR terminals showed different profiles.

Figure 3.

Rat corpus cavernosum. (A) VAChT-IR terminals along smooth muscle bundles. FITC-immunofluorescence. (B) same section as in (A). NOS-IR terminals displaying profiles (arrows) coinciding with VAChT-IR terminals in (A). Texas Red (TR)-immunofluorescence. (C) Branch of a central artery surrounded by a plexus of VAChT-IR terminals. FITC-immunofluorescence. (D) Same section as in (C). VIP-IR terminals with profiles (arrows) coinciding with VAChT-IR terminals in (C). TR-immunofluorescence. (E) Branch of a central artery and smooth muscle bundles with NOS-IR terminals. FITC-immunofluorescence. (F) Same section as in (E). VIP-IR terminals with profiles (arrows) coinciding with NOS-IR terminals in (E). TR-immunofluorescence. Bars=100 μm.

Figure 5.

Rat corpus cavernosum. Confocal microscopy. (A) VAChT-IR nerve varicosities. FITC-immunofluorescence. (B) same sections as in (A). NOS-IR nerve varicosities co-existing with VAChT-IR varicosities in (A). Texas Red (TR)-immunofluorescence. (C) VAChT-IR nerve varicosities. FITC-immunofluorescence. (D) same sections as in (C). VIP-IR nerve varicosities co-existing with VAChT-IR varicosities in (C). Texas Red (TR)-immunofluorescence. (E) NOS-IR nerve varicosities. FITC-immunofluorescence. (F) same sections as in (E). Separate TH-IR nerve varicosities. TR-immunofluorescence. Each image consists of 22 consecutive sections with 0.30 μm between adjacent sections. Bars=10 μm.

Figure 4.

Rat corpus cavernosum. (A) Branch of a central artery surrounded by VAChT-IR terminals. FITC-immunofluorescence. (B) Same section as in (A). TH-IR terminals displaying profiles which are similar, but not coinciding with VAChT-IR terminals in (A). TR-immunofluorescence. (C) Branch of a central artery surrounded by a plexus of VAChT-IR terminals. TR-immunofluorescence. (D) Same section as in (C). NPY-IR terminals displaying profiles, some of which are similar to VAChT-IR terminals in (C). FITC-immunofluorescence. (E) Branch of a central artery surrounded by VAChT-IR terminals following chemical sympathectomy. TR-immunofluorescence. (F) Same section as in (E). Single remaining NPY-IR terminals (compare (D)), which are similar to VAChT-IR terminals in (E). FITC-immunofluorescence. Bars=100 μm.

Following chemical sympathectomy with 6-OHDA, the PGP-IR terminals in the smooth muscle septa were reduced to a moderate number (Figure 1), whereas no TH- and NPY-IR terminals were detected. In comparison, in the plexuses around central and helicine arteries, no changes in the number of PGP-IR terminals could be observed. However, no plexuses of TH-IR terminals were discovered. Single NPY-IR terminals remained, which showed coinciding profiles with VAChT-IR terminals. In addition, the number and distribution of VAChT-, VIP-, nNOS-, and CGRP-IR terminals, in smooth muscle septa as well as in vascular plexuses, were not changed.

In the endothelial cells of the central and helicine arteries, sparse eNOS immunoreactivity was observed, whereas in endothelial cells lining the smooth muscle septa of the cavernous spaces, no eNOS- or HO-immunoreactivy could be detected.

Functional studies

Relaxation of noradrenaline-contracted preparations

Spontaneous contractile activity was not observed in any of the rat isolated cavernous preparations (n=37, N=24). Reproducible, contractile responses to NA, amounting to 1.7±0.2 mN (n=22, N=22), and to ET amounting to 2.5±0.6 (n=9, N=9) were obtained. Pretreatment of the strips with NPY 10−6 M for 15 min did not change the concentration-response curve for NA (n= 6, N= 6).

Cumulative addition of NO to NA-contracted strips, produced concentration-dependent and rapid relaxant responses (Figure 6). The pIC50 value for NO was 5.49±0.34. Pretreatment with ODQ (10−6 M), significantly counteracted the effect of NO in (Figure 5). A higher concentration of ODQ (10−5 M) had no additional effect. CO, in the same concentrations as used for NO, was without effect (n=5, N=5). Carbachol 10−5 M had a small relaxant effect (8±2%; n=6, N=6), and also VIP had a poor relaxant action, which at 10−6 M amounted to 11±3% (n=5, N=5). The relaxant effect of CGRP was small, and at 10−6 M, it measured 18±3% (n=6, N=6).

Figure 6.

(A) Relaxant effect of nitric oxide (NO; n=13, N=12) on isolated preparations of rat corpus cavernosum (CC) contracted with l-noradrenaline (NA; 10−5 M), before and after pretreatment with ODQ (10−6 M; n=6, N=6). Values are given as mean±s.e.mean. (B) Tracing describing the relaxations by NO (M), added cumulatively, in one NA-contracted rat CC preparation. (C) Same preparation as in (B). Tracing showing the relaxant effect of NO after pretreatment with ODQ (10−6 M). Unfilled circles: NO; filled circles NO+ODQ. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Electrically-induced responses

Stimulation of preparations at baseline level produced frequency-dependent contractile responses (n=6, N=6), which were abolished by TTX 10−6 M. Prazosin effectively counteracted the contractions produced by EFS, and at 10−7 M, the electrically-induced responses were abolished. The pIC50 value for prazosin was 8.85±0.22. Contractions induced by electrical stimulation were to a limited degree counteracted by VIP, and at a concentration of 10−7 M, a maximal mean inhibitory effect of 11±4% was obtained (n=5, N=5). CGRP and NPY (10−9–10−6 M) had no effect on baseline tension. CGRP concentration-dependently counteracted the electrically-induced contractions, and at 10−7 M, a maximal mean inhibitory response of 43±6% (n=6, N=6) was attained. Contractile responses elicited by EFS were effectively enhanced by NPY in a concentration-dependent manner. At 10−6 M, the highest peptide concentration used, the contractions were increased by 61±10% (n=6, N=6).

In ET-contracted preparations, EFS (5 s stimulation) generated frequency-dependent and TTX-sensitive (n=6, N=6) responses; a contractile twitch followed by a fast relaxant response (Figure 7). After cessation of stimulation, there was a recovery of tension, and then a slow, second relaxant phase (off-responses). At any investigated frequency, pretreatment with 10−4 M L-NNA (n=5, N=5), or 10−6 M ODQ (n=5, N=5) enhanced the initial EFS-induced contraction and abolished the first relaxant phase. The second relaxant phase was unaffected by either drug.

Figure 7.

(A) Inhibitory effect of electrical field stimulation (EFS; 5 s) in rat isolated corpus cavernosum (CC; n=6, N=6) contracted with endothelin1 (ET; 3×10−8 M), before and after pretreatment with Nω-nitro-L-arginine (L-NNA; 10−4 M). Values are given as mean±s.e.mean. (B) Tracing showing the effect of EFS in one ET-contracted preparation of rat CC. Unfilled circles: phase I (first relaxant phase); filled circles: phase I+L-NNA; unfilled triangles: phase II (second relaxant phase); filled triangles: phase II+L-NNA. *P<0.05; ***P<0.001.

In order to better visualize the nature of the electrically-induced response in ET-contracted preparations, continuous EFS (15 s) at 18 Hz, was applied to the strips (Figure 8). The same responses as after 5 s stimulation were observed; however, the first relaxant phase was extended (Figure 8A and C). The initial contractile twitch amounted to 135±6% (n=8, N=8). Pretreatment with L-NNA or ODQ enhanced this contraction to 228±13% (P<0.001) and 243±41% (P<0.01), respectively Figure 8B and D). The first relaxant phase amounted to 48±4%; it was abolished by pretreatment with L-NNA or ODQ (Figure 8B and D). The second relaxant response amounted to 41±7%. After pretreatment with L-NNA or ODQ, there was no off-contraction, but the second relaxant response remained. L-NNA or ODQ did not significantly influence the second relaxant phase (Figure 8B and D), and the relaxation amounted to 56±12 and 62±10%, respectively.

Figure 8.

(A and C) Tracing describing the effect of 15 s continuous electrical field stimulation (EFS) in two separate preparations of rat corpus cavernosum CC contracted with endothelin-1 (ET; 3×10−8 M). (B) Same preparation as in (A). Effect of 15 s EFS after pretreatment with L-NNA (10−4 M). (D) Same preparation as in (C). Effect of 15 s EFS after pretreatment with ODQ (10−6 M). Incomplete lines represents resting tension level before addition of endothelin-1. Thick complete lines correspond to the duration of stimulation. Roman numerals represent the first (I) and second (II) relaxant phases.

Discussion

The use of rats for the study of penile erection in vivo, has received considerable attention (Andersson & Wagner, 1995). However, the rat CC tissue, which should make possible detailed studies of neurotransmission and the effects of drugs, has not been extensively used, probably due to technical difficulties in obtaining suitable in vitro preparations (Dail et al., 1986; Italiano et al., 1994). In this study, a convenient, CC strip preparation has been characterized, and effects of EFS and transmitters possibly involved in erectile responses have been correlated with immunocytochemical findings.

Immunoreactivity for NOS has been demonstrated in nerves of the rat CC (Burnett et al., 1992; Alm et al., 1993; Dail et al., 1995), and in accordance with these findings, the present study showed NOS-IR nerve trunks and NOS-IR nerve fibres interspersed in bundles of smooth muscles surrounding the sinusoidal spaces, and varicose NOS-IR nerve fibres were detected within the wall of arteries. Preferably, the number of NOS-containing nerves should be related to the total amount of nerves. We estimated the total number of nerves by using the non-specific nerve-marker, PGP, and found that the number of NOS-IR nerve fibres was moderate.

By retrograde labelling, several investigators have found that the majority of penile nerves containing immunoreactivity for NOS is derived from the pelvic plexus (Ding et al., 1993; 1995; Domoto & Tsumori, 1994; Dail et al., 1995; Vanhatalo & Soinila, 1995), and it was suggested (Dail et al., 1995) that most neurons derived from the pelvic plexus and destined for the penis, comprised a uniform population, which were capable of synthesizing NO, and demonstrated cholinergic characteristics. We found by double immunolabelling that VAChT- and NOS-IR terminals, and VAChT- and VIP-IR terminals, and NOS- and VIP-IR terminals generally showed coinciding profiles, whereas those of VAChT- and TH-, and NOS- and TH-IR terminals were running closely together, although the profiles were not coinciding. In general VAChT-IR nerves were fewer than those positive for AChE, which is not surprising, since AChE staining is not specific for cholinergic nerves (Lincoln & Burnstock, 1993). Since VAChT should be specific for cholinergic neurons, the present findings provide direct evidence for the view that the NOS-containing penile neurons are cholinergic. However, the VAChT-containing nerves were fewer than those containing NOS, and it cannot be excluded that NOS may occur also in non-VAChT neurons, and among those, a population of nerves containing only NOS (Kaleczyk et al., 1994; Elfvin et al., 1997). Jen et al. (1996) reported that NOS and TH were co-localized in nerves supplying the postnatal human penis. Tamura et al. (1995) reported that also in the human penis, NOS could be found in nerves containing TH, suggesting that NO may be generated by adrenergic nerves. In the present study, as verified with confocal laser scanning microscopy, nNOS- and TH-, VAChT- and TH-, or VIP- and TH-immunoreactivities were found in separate nerve fibres and terminals. Further support of this finding, the presently performed chemical sympathectomy abolished TH-IR nerve structures in the CC, and reduced the number of NPY-IR nerves, whereas the amount and distribution of nerves containing immunoreactivities for NOS, VAChT, and VIP were unaffected. nNOS/VAChT/VIP-IR and TH-IR nerves were however found to run close together in similar distribution patterns, which make possible cholinergic modulation of the release of NA from adrenergic nerves.

Inhibitory neurotransmission in isolated cavernous tissue from, e.g., rabbits, dogs, and humans, involves the release of NO (Andersson & Wagner, 1995). This was suggested also for isolated rat CC (Italiano et al., 1994). The present study verified that precontracted preparations of rat CC respond with frequency-dependent relaxations to transmural stimulation of nerves, and showed that the relaxations were significantly attenuated by blockade of the synthesis of NO. Pretreatment with the inhibitor of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), ODQ, significantly counteracted the relaxant effects obtained by transmural stimulation of nerves, and, as seen by high-speed recordings, the appearances of the electrically-induced responses after blockade of NOS or sGC were similar, as were the effects of inhibition of either enzyme. The inhibitory responses obtained by EFS in rat isolated CC under the present experimental conditions, comprised two relaxant phases. Initially, one rapid, L-NNA- and ODQ-sensitive relaxation was seen, followed by a slow relaxant component, which was insensitive to inhibition of NOS or sGC. This finding suggests that additional nerve-released agents may directly relax the rat CC.

In NA-contracted preparations, exogenously applied NO produced rapid and concentration-dependent relaxations, which also were effectively counteracted by inhibition of sGC. After blockade of sGC, some relaxant effects persisted at higher NO concentrations, and it may be speculated that the inhibitory effect of ODQ was overcome by the increased amount of NO. It could also reflect that NO, at high concentrations, acts by additional mechanisms, unrelated to stimulation of cGC. In cultured human smooth muscle CC cells, NO was proposed to modulate the activity of the Na+/K+ ATPase activity (Gupta et al., 1995), but whether or not this can explain the present observation is unclear. In other smooth muscle preparations, NO was shown to induce hyperpolarization (Ward et al., 1992), but if this is the case in CC tissue is not known.

The endothelium may provide a complementary source of NO during penile erection, and ACh-induced relaxation of erectile tissue has been shown to involve the release of NO from endothelial cells (Ignarro et al., 1987; Palmer et al., 1987; Andersson & Wagner, 1995). Although a positive NADPHd reaction has been described in some parts of the sinusoidal endothelium of the rat penis (Keast, 1992), this has not been found by later investigations (Schirar et al., 1994; Dail et al., 1995). In the present investigation, no immunoreactivity for eNOS could be demonstrated in endothelial cells of the sinusoidal endothelium of the rat CC, a finding supporting the observations of Schirar et al. (1994) and Dail et al. (1995). Furthermore, we found that exogenously applied carbachol induced only a small relaxant effect in NA-contracted preparations, which means that NO released from the endothelium lining the cavernous sinuses, should not be of major importance for erection. eNOS may be present in the endothelium of the rat penile arteries (Dail et al., 1995), but it is unclear to what extent NO derived from this endothelium contributes to the erectile response under physiological conditions. Upregulation of eNOS, compensating for loss of nNOS was suggested to explain the fact that nNOS knockout mice had normal erections (Burnett et al., 1996). Since relaxant effects of carbachol or ACh have been demonstrated in precontracted CC tissue from other mammals, including man, species differences concerning the role of endothelially derived NO seem to exist, which should be taken into consideration when studying penile erection in different models. This also appears to be the case for VIP, NPY and CGRP when comparing their functional effects in isolated CC from dog, rabbit, and man, with those in the rat.

NPY has been localized to nerves of the penile erectile tissue of several species, but evidence for a functional role of the peptide is inconsistent (see Andersson & Wagner, 1995). In the present study, immunoreactivity for NPY was intimately related to that of TH, supporting previous findings that NPY is localized mainly to adrenergic neurons (see Lundberg, 1996). In functional experiments, NPY effectively enhanced nerve-induced α-adrenoceptor-mediated contractile activity, possibly by a prejunctional, facilitatory action on noradrenergic nerves, since it did not change the concentration-response curve for NA. This finding suggests that the peptide may be involved in penile detumescence in the rat. After chemical sympathectomy, a fraction of NPY-IR terminals remained. However, the possible function of these nerves is unknown.

Immunoreactivity for CGRP, and binding-sites for the peptide, have been shown in CC, but the demonstrated functional effects of CGRP in vitro have been small (Andersson & Wagner, 1995). In the rat CC, few CGRP-IR nerve fibres were found. However, since an approximately 40% reduction of EFS-induced contractile activity in isolated CC preparations was observed, a modulatory role for CGRP in the erectile response of the rat CC cannot be excluded. This may be mediated partly by a prejunctional inhibitory effect on noradrenergic nerves, since the relaxant effects of CGRP on NA-contracted preparations was small.

Demonstration of HO-activity, and relaxant effects of CO in gastrointestinal cardiovascular, and urogenital tissues, suggest a role for CO as a messenger molecule in peripheral organ systems (Furchgott & Jothianandan, 1989; Ny et al., 1996; Werkström et al., 1997; Hedlund et al., 1997). In isolated cavernous tissue from rabbits, the involvement of CO in nerve-mediated relaxant responses, could not be demonstrated (Kim et al., 1994). HO-IR nerve structures have been described in human CC and corpus spongiosum (CS), and exogenously applied CO has been shown to induce relaxant effects in preparations of CC and CS tissue from humans (Hedlund et al., 1996). In the rat CC, immunoreactivity for HO was found to be distributed similarly as immunoreactivities for NOS, VAChT, or VIP in nerve structures. However, cumulative addition of CO to NA-contracted CC-strips did not alter the contractile state of the preparations, and a role for CO in the regulation of smooth muscle tone in the rat penis seems unlikely. If the HO/CO system has a messenger, or neuromodulatory function in the urogenital region has thus not been established, and should be further examined.

In summary, NOS-, VAChT-, and VIP-immunoreactivities are co-localized in nerve fibres of the rat cavernous erectile tissue, and seem to represent a population of penile parasympathetic cholinergic neurons. Nerve-mediated inhibitory responses in precontracted rat isolated CC are mediated by NO and by other, as yet unknown transmitters. In the rat CC, endothelially-derived NO may be of minor importance for penile erection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council (grant no 6837 and 11205), the Royal Physiographic Society, the Foundation of Crafoord, Magnus Bergvall, Åke Wiberg, Thelma Zoéga, and the Medical Faculty, University of Lund, Sweden.

Abbreviations

- AChE

acetylcholinesterase

- CC

corpus cavernosum

- cGMP

cyclic guanosine 3′, 5′monophosphate

- CGRP

calcitonin gene-related peptide

- CO

carbon monoxide

- EFS

electrical field stimulation

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- ET-1

endothelin-l

- HO-1

inducible heme oxygenase

- HO-2

constitutive heme oxygenase

- L-NNA

Nω-nitro-L-arginine

- NA

l-noradrenaline

- NADPHd

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate diaphorase

- IR

immunoreactive

- nNOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- NO

nitric oxide

- NPY

neuropeptide Y

- ODQ

1H-[1,2,4]-oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one

- 6-OHDA

6-hydroxydopamine

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PGP

protein gene product 9.5

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- VAChT

vesicular acetylcholine transporter

- VIP

vasoactive intestinal polypeptide

References

- ALM P., LARSSON B., EKBLAD E., SUNDLER F., ANDERSSON K.E. Immunohistochemical localization of peripheral nitric oxide synthase-containing nerves using antibodies raised against synthetized C- and N-terminal fragments of a cloned enzyme from rat brain. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1993;148:421–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1993.tb09578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDERSSON K.-E., WAGNER G. Physiology of penile erection. Physiol. Revs. 1995;75:191–236. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARVIDSSON U., REIDL M., ELDE R., MEISTER B. Vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) protein: A novel and unique marker for cholinergic neurons in the central and peripheral nervous systems. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997;378:454–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNETT A.L., LOWENSTEIN C.J., BREDT D.S., CHANG T.S.K., SNYDER S.H. Nitric oxide: A physiologic mediator of penile erection. Science. 1992;257:401–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1378650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNETT A.L., NELSON R.J., CALVIN D.C., LIU J.-L., DEMAS D.E., KLEIN S.L., KRIEGFELD L.J., DAWSON V.L., DAWSON T.M., SNYDER S.H. Nitric oxide-dependent penile erection in mice lacking neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Molec. Med. 1996;2:288–296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNETT A.L., TILLMAN S.L., CHANG T.S.K., EPSTEIN J.I, , LOWENSTEIN C.J., BREDT D.S., SNYDER S.H., WALSH P.C. Immunohistochemical localization of nitric oxide synthase in the autonomic innervation of the human penis. J. Urol. 1993;150:73–76. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAIL W.G., BARBA V., LEYBA L., GALINDO R. Neuronal and endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity in rat penile erectile tissue. Cell Tiss. Res. 1995;282:109–116. doi: 10.1007/BF00319137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAIL W.G., MINORSKI N., MOLL M.A., MANZANARES K. The hypogastric nerve pathway to penile erectile tissue: Histochemical evidence supporting vasodilator role. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1986;15:341–349. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(86)90019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DING W.G., MINORSKI N., MOLL M.A., MANZANARES K. The major pelvic ganglion is the main source of nitric oxide synthase-containing fibres in penile erectile tissue of the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 1993;164:187–189. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90888-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DING Y.Q., TAKADA M., KANEKO T., MIZUNO N. Co-localization of vasoactive intestinal peptide immunoreactivity and nitric oxide in penis-nervating neurons in the major pelvic ganglion of the rat. Neurosci. Res. 1995;22:129–131. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(95)00884-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOMOTO T., TSUMORI T. Co-localization of nitric oxide synthase and vasoactive intestinal peptide immunoreactivity in neurons of the major pelvic ganglion projecting to the rat rectum and penis. Cell. Tiss. Res. 1994;278:273–278. doi: 10.1007/BF00414170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELFVIN L.G., HOLMBERG K., EMSON P., SCHEMANN M., HOKFELT T. Nitric oxide synthase, choline acetyltransferase, catecholamine enzymes and neuropeptides and their colocalization in the anterior pelvic ganglion, the inferior mesenteric ganglion and the hypogastric nerve of the male guinea pig. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 1997;14:33–49. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(97)10010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FINBERG J.P., LEVY S., VARDI Y. Inhibition of nerve stimulation-induced vasodilation in corpora cavernosa of the pithed rat by blockade of nitric oxide synthase. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;108:1038–1042. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13502.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FURCHGOTT R.F., JOTHIANANDAN D. Endotheliumindependent relaxation of rabbit aorta by carbon monoxide. FASEB J. 1989;3:A1177. [Google Scholar]

- GU J., POLAK J.M., PROBERT L., ISLAM K.N., MARANGOS P.J., MINA S., ADRIAN T.E., MCGREGOR G.P., O'SHAUGNHNESSY D.J., BLOOM S.R. Peptidergic innervation of the male genital tract. J. Urol. 1983;130:386–391. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)51174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUPTA S., MORELAND R. B., MUNARRIZ R., DALEY J., GOLDSTEIN I., SAENZ DE TEJADA I. Possible role of Na+K+ATPase in the regulation of human corpus cavernosum smooth muscle contractility. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:2201–2206. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEDLUND P., EKSTRÖM P., LARSSON B., ALM P., ANDERSSON K.E. Heme oxygenase and NO-synthase in the human prostate–relation to adrenergic, cholinergic and peptide-containing nerves. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1997;63:115–126. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(96)00139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEDLUND P., NY L., ANDERSSON K.-E. Heme oxygenase and carbon monoxide in the human corpus spongiosum. Int. J. Impotence Res. 1996;8:A26. [Google Scholar]

- HERBISON A. E., SIMONIAN S. X., NORRIS P. J., EMSON P.C. Relationship of neuronal nitric oxide synthase immunoreactivity to GnRH neurons in the ovariectomized and intact female rat. J. Neuroendocrinol. 1996;8:73–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1996.tb00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLMSTEDT B. A modification of the thiocholine method for determination of cholinesterase. II. Histochernical application. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1957;40:331–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1957.tb01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IGNARRO L.J., BUGA G.M., WOOD K.S., BYRNS R.E., CHAUDHURY G. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor produced and released from artery and vein is nitric oxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1987;84:9265–9269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITALIANO G., CALABRO A., PAGANO F. A simplified in vitro preparation of the corpus cavernosum as a tool for investigating erectile pharmacology of the rat. Pharmacol. Res. 1994;30:325–334. doi: 10.1016/1043-6618(94)80012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JEN P.Y.P., DIXON J.S., GEARHART J.P., GOSLING J.A. Nitric oxide synthase and tyrosine hydroxylase are colocalized in nerves supplying the postnatal human genitourinary organs. J. Urol. 1996;155:1117–1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON G.D.M., NOGUEIRA ARAUJO G.M. A simple method of reducing the fading of immunofluorescence during microscopy. J. Immunol. Meth. 1981;43:349–350. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(81)90183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KALECZYC J., TIMMERMANS J.P., MAJEWSKI M., LAKOMY M., MAYER B., SCHEUERMANN D.W. NO-synthase-containing neurons of the pig inferior mesenteric ganglion, part of them innervating the ductus deferens. Acta Anat (Basel) 1994;151:62–67. doi: 10.1159/000147644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEAST J.R. A possible neural source of nitric oxide in the rat penis. Neurosci. Lett. 1992;143:69–73. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90235-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM Y.C., DAVIES M.G., MARSON L., HAGEN P.O., CARSON C.C. Lack of effect of carbon monoxide inhibitor on relaxation induced by electrical field stimulation in corpus cavernosum. Urol. Res. 1994;22:291–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00297197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOELLE G.B., FRIEDENWALD J.S. A histochemical method for localizing cholinesterase activity. Proc. Soc. Exptl. Biol. Med. 1949;70:617–622. doi: 10.3181/00379727-70-17013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINCOLN J., BURNSTOCK G.Autonomic innervation of the urinary bladder and urethra The Autonomic Nervous System 1993Vol. 6Harwood Academic Publishers, London, UK; 33–68.Chapter 8, C.A. Maggi., (ed) pp [Google Scholar]

- LUNDBERG J.M. Pharmacology of cotransmission in the autonomic nervous system: integrative aspects on amines, neuropeptides, adenosine triphosphate, amino acids and nitric oxide. Pharmacol. Rev. 1996;48:113–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUNDBERG L.-M., ALM P., WHARTON J., POLAK J.M. Protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5)–A new neuronal marker visualizing the whole uterine innervation and pregnancy-induced and developmental changes in the guinea-pig. Histochemistry. 1988;90:9–17. doi: 10.1007/BF00495700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATTHEWS D.A., NADLER J.V., LYNCH G.S., COTMAN C.W. Development of cholinergic innervation in the hippocampal formation of the rat. I. Histochemical demonstration of acetylcholinesterase activity. Develop. Biol. 1974;36:130–141. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(74)90196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NY L., ALM P. , EKSTRÖM P., LARSSON B.L., GRUNDEMAR L., ANDERSSON K.E. Localization and activity of haem oxygenase and functional effects of carbon monoxide in the feline lower oesophageal sphincter. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:392–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PALMER R.M.J., FERRIDGE A.G., MONCADA S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature. 1987;327:524–526. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAND M. J., LI C.G. Nitric oxide as a neuro transmitter in peripheral nerves: Nature of transmitter and mechanism of transmission. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 1996;57:659–682. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.003303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHIRAR A., GIULIANO F., RAMPIN O., ROUSSEAU J.-P. A large proportion of pelvic neurons innervating the corpora cavernosa of the rat penis exhibit NADPH-diaphorase activity. Cell Tiss. Res. 1994;278:517–525. doi: 10.1007/BF00331369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEERS W.D., MCONNELL J., BENSON G. Anatomical localization and some pharmacological effects of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in human and monkey corpus cavernosum. J. Urol. 1984;132:1048–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49997-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAMURA M., KAGAWA S., KIMURA K., KAWANASHI Y., TSURUO Y., ISHIMURA K. Coexistence of nitric oxide synthase, tyrosine hydroxylase and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in human penile tissue–a triple histochemical and immunohistochemical study. J. Urol. 1995;153:530–534. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199502000-00077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAMURA M., KAGAWA S., TSURUO Y., ISHIMURA K., KIMURA K., KAWANASHI Y. Localization of NADPH diaphorase and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-containing neurons in the efferent pathway to the rat corpus cavernosum. Eur. Urol. 1997;32:100–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANHATALO S., SOINILA S. Direct nitric oxide-containing innervation from the rat spinal cord to the penis. Neurosci. Lett. 1995;199:45–48. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12012-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WARD S.M., MCKEEN E.S., SANDERS K.M. Role of nitric oxide in non adrenergic inhibitory junction potentials in canine ileocolonic sphincter. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;105:776–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb09056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WERKSTRÖM V., NY L., PERSSON K., ANDERSSON K.E. Carbon monoxide-induced relaxation and distribution of haem oxygenase isoenzymes in the pig urethra and oesophagogastric junction. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:312–318. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WESSENDORF M.W., ELDE R.P. Characterization of an immunofluorescence technique for the demonstration of coexisting neurotransmitters within nerve fibres and terminals. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1985;33:984–994. doi: 10.1177/33.10.2413102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]