Abstract

The glycosaminoglycan heparin inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation and migration, but the mechanism of its antiproliferative action remains unclear. Heparin has been reported to bind to high affinity cell surface sites on animal VSMC before undergoing receptor mediated endocytosis resulting in signal transduction into the cytoplasm and modulation of genes involved in proliferation. In this study, we have characterized the binding of [3H]-heparin to human saphenous vein-derived VSMC and examined whether there is any relationship between the affinity of [3H]-heparin binding and the inhibitory effect of heparin and its structural analogues on DNA synthesis.

At 4°C [3H]-heparin binding to human VSMC occurred in a specific, time and concentration-dependent manner and was not influenced by the removal of calcium ions. Binding of the ligand appeared to occur to the cell surface and was both saturable and reversible. Kinetic and steady state data indicated a single class of binding sites.

The pharmacology of [3H]-heparin binding was examined in displacement studies using unlabelled heparin and structural analogues. A comparison of the rank potencies of heparin, heparan sulphate fraction II, low molecular weight heparin and trehalose octasulphate showed that there was a marked discrepancy between their estimated affinities in the binding assays and their effect on DNA synthesis.

In summary, we have characterized the heparin binding site on human saphenous vein-derived VSMC. Our findings suggest that the action of heparin and its analogues on DNA synthesis does not simply reflect an interaction with the cell-associated heparin binding site defined in these studies, but may also be determined by the internalization and metabolism of the glycosaminoglycan(s).

Keywords: DNA synthesis, heparin, human vascular smooth muscle, radioligand binding

Introduction

The highly sulphated glycosaminoglycan heparin, which comprises repeating units of uronic acid and glucosamine sugars is a potent physiological inhibitor of vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation (Clowes & Karnovsky, 1977; Hoover et al., 1980) and migration (Majack & Clowes, 1984). The molecular mechanism of action for heparin remains unclear although multiple targets have been proposed for its antiproliferative effects. Heparin regulates the expression of extracellular matrix proteins (Majack et al., 1985; Snow et al., 1990) and suppresses the induction of matrix-degrading enzymes (Au et al., 1992a,1992b; Clowes et al., 1992; Kenagy et al., 1994) which play a key role in cell migration and proliferation. In keeping with its antiproliferative effect, heparin has been shown to inhibit the expression of mitogen-activated genes (e.g. cellular proto-oncogenes such as c-fos, c-jun, c-myb (Pukac et al., 1992; Reilly et al., 1989)) and other protein kinases (e.g. protein kinase C (Castellot et al., 1989; Ottlinger et al., 1993) and serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase (Delmolino & Castellot, 1997)). Heparin may also reduce the mitogenic activity of some cytokines, either by interacting with them (Lindner et al., 1992) or their receptors (Fager et al., 1992). In an alternative model, it has been proposed that transforming growth factor β1 potentiates the antiproliferative effect of heparin (McCaffrey et al., 1989). As heparin exerts multiple effects on VSMC it is not known whether these effects occur through a single common pathway or represent a number of different pathways.

Heparin inhibits VSMC growth both in vivo and in vitro (Clowes & Karnovsky, 1977; Hoover et al., 1980). In most animal models heparin inhibits intimal hyperplasia which occurs following vascular injury (Clowes & Karnovsky, 1977; Clowes & Reidy, 1991). We and others have, however, shown that cells grown from human restenotic vein grafts (Chan et al., 1993b) and atherosclerotic lesions (Caplice et al., 1994) exhibit reduced growth inhibition by heparin. Although there is a considerable inter-individual variation in the growth inhibition of human VSMC by heparin (Chan et al., 1993a,1993b; Munro et al., 1994), we have previously performed extensive studies to show that the antiproliferative effect of heparin is consistent over five passages in VSMC from individual patients (Munro et al., 1994). Furthermore, we have recently reported that there is a relationship between the sensitivity of human VSMC to growth inhibition by heparin and the number of heparin binding sites (Refson et al., 1998).

In terms of its mechanism of action, heparin has been reported to bind to high affinity sites on the cell surface of animal VSMC (Castellot et al., 1985) before undergoing internalization by receptor-mediated endocytosis. This is believed to result in signal transduction into the cytoplasm and modulation of a number of genes involved in proliferation and has, therefore, lent support to a cellular site of action for the antiproliferative effect of heparin. In this investigation, we set out to characterize the binding of heparin to human VSMC and to determine what, if any relationship, exists between the affinity of [3H]-heparin binding and the inhibitory effect of heparin and its structural analogues on DNA synthesis.

Methods

Cell culture

Human VSMC were grown from saphenous vein, using an explant technique as described previously (Chan et al., 1993a). Redundant saphenous veins were obtained from patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery in accordance with the guidelines of the local Ethics Committee. Cultures were established in standard growth medium comprising Dulbecco's modification of Eagle's medium (DMEM) buffered with HEPES 25 mM and supplemented with 15% (v v−1) foetal calf serum (FCS), l-alanyl-l-glutamine (Glutamax-I) 4 mM, penicillin (100 U ml−1), streptomycin (100 μg ml−1) and gentamicin (25 μg ml−1). Cultures were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 (v v−1) in air at 37°C. Immunocytochemical studies of these VSMC have shown positive staining for the smooth muscle isoform of α-actin (Skalli et al., 1987) and smooth muscle-specific myosin heavy chains, but negative staining for factor VIII-related antigen, a marker for endothelial cells (unpublished data).

[3H]-heparin binding assays

VSMC, at the second passage, were plated into 24-well plates at 105 cells ml−1, 1.0 ml well−1 in standard growth medium supplemented with 15% FCS and allowed to attach overnight. The cells were rendered quiescent by removing the growth medium, washing twice with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline without calcium and magnesium (PBS-A) and maintained in growth medium supplemented with only 0.4% (v v−1) FCS for a further 72 h. These quiescent cells were cooled to 0–4°C and washed with ice-cold PBS-A prior to the binding assays which were conducted on ice to prevent internalization of ligand.

Saturation assay

Saturation binding assays were conducted by the addition of precooled solutions of [3H]-heparin prepared in serum-free DMDM at a range of concentrations from 5×10−9–10−6 M. Assays were performed in triplicate wells for 45 min and the cells maintained on ice throughout. Non-specific binding was determined by incubation under the same conditions with precooled solutions of [3H]-heparin prepared in serum-free DMEM (over the same concentration range) with excess unlabelled heparin (10−5 M). Following the incubation period, the [3H]-heparin containing solution was removed and the cells washed three times with ice-cold PBS-A. Cells were solubilized in 1 M sodium hydroxide solution and aliquots of the cell lysates transferred to scintillation vials to which Ecoscint was added. Radioactivity was measured in a 1900CA TriCarb scintillation counter (Canberra Packard, Pangbourne, U.K.) to determine the amount of [3H]-heparin bound to the cells.

Association and dissociation of [3H]-heparin binding from human VSMC

The binding of [3H]-heparin was examined with respect to time and binding assays were conducted under the conditions described above. Total [3H]-heparin binding was assessed by incubation with precooled solutions of [3H]-heparin (10−7 M) prepared in serum-free DMEM. Assays were conducted in triplicate for up to 2 h and maintained on ice. Non-specific binding was determined by incubation under the same conditions with precooled solutions of [3H]-heparin (10−7 M) prepared in serum-free DMEM with a 100 fold excess of unlabelled heparin (10 −5 M).

Following on from the association studies which showed that steady state was reached within 30 min, the dissociation time course for [3H]-heparin was examined in these cells. Total binding was determined by incubating cells with [3H]-heparin (10−7 M) in serum-free DMEM for 30 min and non-specific binding with [3H]-heparin (10−7 M) in the presence of a 100 fold excess unlabelled heparin (10−5 M). All the wells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS-A and a 100 fold excess of unlabelled heparin (10−5 M) prepared in serum-free DMEM was added to the cells. The cells were maintained on ice for up to 2 h and washed with ice-cold PBS-A and lysed prior to liquid scintillation counting as described above.

Specificity of [3H]-heparin binding

The pharmacology of [3H]-heparin binding to human VSMC was examined by performing displacement analysis of radioligand binding. Assays were conducted on ice for 30 min as described above using a range of concentrations (10−9–10−5 M) of unlabelled heparin, low molecular weight heparin, chondroitin sulphate, dermatan sulphate, trehalose octasulphate or heparan sulphate fractions in the presence of [3H]-heparin (10−7 M).

Requirement of calcium ions for [3H]-heparin binding

Displacement assays were conducted (as described above) using unlabelled heparin as the displacing ligand. The buffer used for these assays comprised (mM) HEPES 10, sodium chloride 120, potassium chloride 5 and either EGTA 1 or calcium chloride 1 and magnesium chloride 1.

DNA synthesis assays

The incorporation of [methyl 3H]-thymidine was assessed as a measure of de novo DNA synthesis as described previously (Patel et al., 1996) using cells at the third passage. Briefly, VSMC were seeded into 96-well plates at confluence in standard growth medium and allowed to attach overnight. The cells were rendered quiescent as described above and maintained either in a supplemented serum-free DMEM (Libby & O'Brien, 1983) or NCTC 109 medium supplemented with HEPES 25 mM, Glutamax-I, 4 mM, 0.25% (w v−1) bovine serum albumin fraction V and antibiotics for a further 72 h. Quiescent cells were stimulated using DMEM supplemented with 15% FCS in the presence or absence of heparin or its analogues (10−7–10−4 M). [methyl 3H]-thymidine was added (1 μCi well−1, 5 μCi ml−1) for the last 6 h of the 30 hour experiment as these human VSMC exhibit a maximal rate of [methyl 3H]-thymidine incorporation in response to FCS during this time interval (Patel et al., 1997).

Proliferation assays

Growth assays were conducted over 14 days as previously described (Chan et al., 1993a) using subconfluent cells. Briefly, VSMC, at the second passage, were plated into 24-well plates at 104 ml−1, 1.0 ml well−1 in standard growth medium supplemented with 15% FCS and allowed to attach overnight and rendered quiescent as described above. Growth was initiated by exposure to DMEM supplemented with 15% FCS in the presence or absence of heparin (100 μg ml−1). Cell counts were performed on triplicate wells every 3–4 days, using a Z1 Coulter counter (Coulter Electronics, Luton, U.K.), following harvesting with 0.25% (w v−1) trypsin in PBS-A containing EDTA 1 mM.

Materials

[3H]-heparin (sodium salt, average molecular weight 18,000, 0.0189 GBq mmol−1) and [methyl 3H]-thymidine (740 GBq mmol−1) were purchased from NEN Life Science Products, (Boston, MA, U.S.A.) and ICN Flow (Thame, U.K.) respectively. Cell culture plastics, supplements and foetal calf serum (FCS) were obtained from Life Technologies, (Paisley, U.K.). Bovine serum albumin (fraction V) and Ecoscint were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim (Lewes, U.K.) and National Diagnostics (Hull, U.K.) respectively. Trichloroacetic and hydrochloric acids were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Loughborough, U.K.). Unless otherwise stated all other reagents were obtained from Sigma (Poole, U.K.).

Unfractionated porcine heparin (average molecular weight 14,000, Payne & Byrne, Birmingham, U.K.), low molecular weight heparin, heparin sulphate fractions and trehalose octasulphate were the generous gift of Dr B. Mulloy, National Institute of Biological Standards and Control, (South Mimms, U.K.). The unfractionated heparin has previously been characterized for its anticoagulant and chemical properties (Johnson & Mulloy, 1976) as well as for its antiproliferative effects on human VSMC in vitro (Chan et al., 1992). Heparan sulphate fractions I and II have mean molecular masses of 25,000 and 8000 daltons respectively (Casu et al., 1983). Heparan sulphate fraction I is less sulphated than fraction II which in turn is less sulphated than the unfractionated heparin. Low molecular weight heparin was prepared by gel permeation chromatography (Johnson & Mulloy, 1976) and characterized as having a mean molecular mass of 5238 (Mulloy et al., 1997). Trehalose octasulphate is a disaccharide of 1400 daltons.

Data analysis

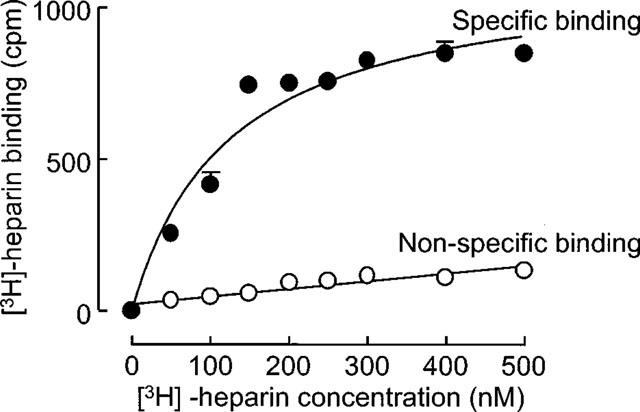

Data are presented as means±s.e.mean of (n) observations. Saturation data from radioligand binding experiments were fitted to a Langmuir function by non-linear regression:

for one site or:

|

for two sites where Y=specific binding at a given [Ligand]. KDn is the dissociation constant for site n and Bmaxn=maximum number of each binding site.

Displacement data were fitted to a logistic function for one site competition:

where Y=specific binding at a [displacer], Maximum=maximum value of curve, Minimum=minimum value of curve, x=log [displacer], pIC50=−log IC50. IC50 values were converted to Ki using the Cheng Prusoff equation (Cheng & Prusoff, 1973).

Association data were fitted to a monoexponential function:

|

where Y=binding at time (t), Ymax=maximum binding, Kobs=apparent onset constant. Similarly, the dissociation rate constant was estimated using:

where Y=binding at time (t), Ymax=maximum displaceable binding, Koff=dissociation rate constant and c=non displaceable binding. The true rate constant (Kon) was calculated as:

and KD was estimated as (Koff) (Kon)−1.

Binding and concentration-response data were fitted using Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, U.S.A.).

Results

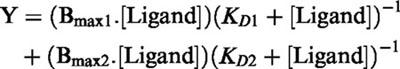

Binding of [3H]-heparin (10−7 M) to human VSMC occurred in a concentration-dependent and saturable manner at 0–4°C as shown in Figure 1. Non-specific binding of [3H]-heparin (10−7 M) accounted for approximately 15% of the total binding as determined in the presence of 100 fold excess unlabelled heparin (10−5 M) under these conditions. In these saturation experiments (n=2), data were best fitted by a single site model. The mean KD derived from these saturation assays was 120 nM (range 110–129 nM, n=2). Bmax was calculated from these data to represent 2–4×106 sites cell−1.

Figure 1.

Saturation isotherm of [3H]-heparin binding to human vascular smooth muscle cells. Radioligand binding was performed on ice for 45 min with [3H]-heparin (10−7 M) either in the presence or absence of 100 fold excess unlabelled heparin. This figure is a representative isotherm of two experiments performed in triplicate on different human cell strains with each point showing the mean±s.e.mean at each point. Non-specific binding was subtracted from total binding to obtain specific binding. The KD and Bmax were calculated as 110 nM and 952 c.p.m. (i.e. ∼4×106 sites cell−1) in the above experiment.

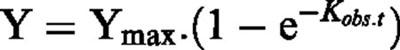

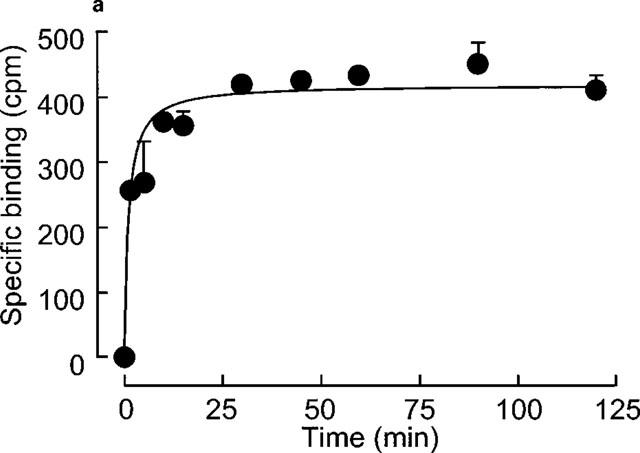

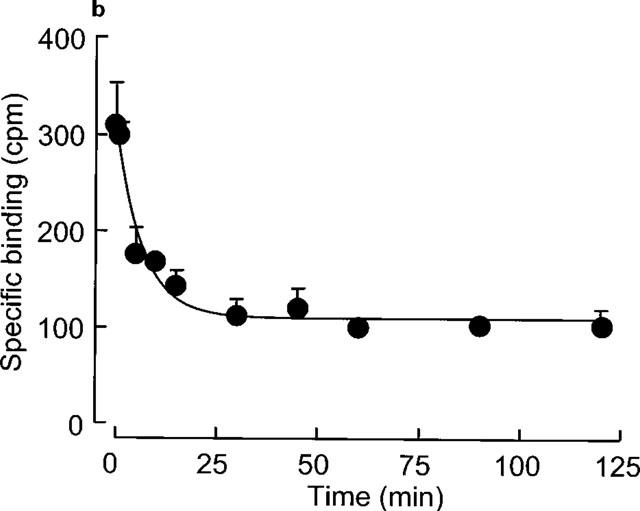

[3H]-heparin (10−7 M) binding to human VSMC reached steady state conditions within 30 min at 0–4°C (Figure 2a) and the apparent onset rate constant (Kobs) was 0.376±0.100 M−1 s−1 (n=4). Dissociation experiments (Figure 2b) showed that about 65% of the bound [3H]-heparin was displaced by the addition of a 100 fold excess cold heparin (10−5 M) and that the offset rate constant was 0.087±0.038 M−1 s−1 (n=3). The onset rate constant was calculated to be 2890083 (M−1). The −log KD for [3H]-heparin binding was determined as 7.5±0.4 (KD=30 nM (11–83 nM geometric standard error, n=4)) which compares with the KD value of 120 nM calculated from the saturation data. Neither the association nor dissociation data were better fitted using a double exponential model, hence providing no evidence of two classes of [3H]-heparin binding sites from the kinetic studies.

Figure 2.

(a) Onset of [3H]-heparin binding to human vascular smooth muscle cells. [3H]-heparin (10−7 M) binding was performed for 2 h in the presence or absence of 100 fold unlabelled heparin. This figure shows a representative example from four experiments performed on different cell strains with each point showing the mean±s.e.mean of triplicates at each time point. Non-specific binding was subtracted from the data which were fitted to a monoexponential association equation as described in the Methods section. (b) Offset of [3H]-heparin binding from vascular smooth muscle cells. Cells were preincubated with [3H]- heparin (10−7 M) for 30 min prior to the addition of unlabelled 100 fold excess heparin. Binding was measured at times up to 2 h following addition of unlabelled heparin. This figure is representative of three experiments performed on different cell strains with each point showing the mean±s.e.mean of triplicates at each time point. The data set are fitted to a monoexponential dissociation equation after subtraction of non-specific binding.

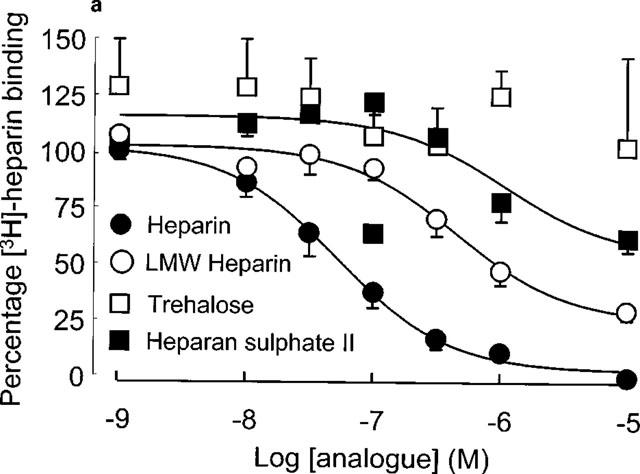

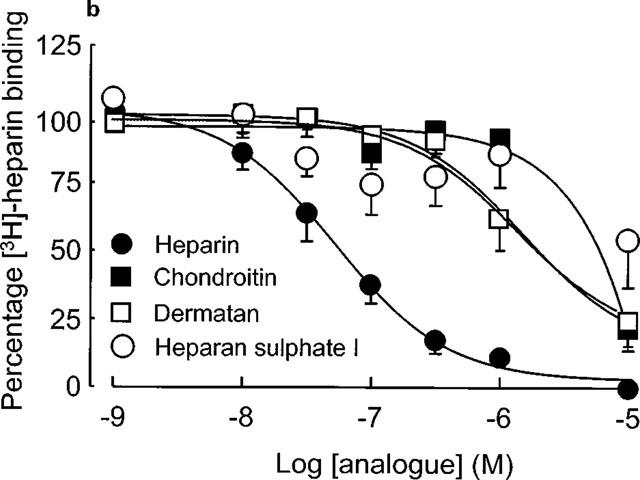

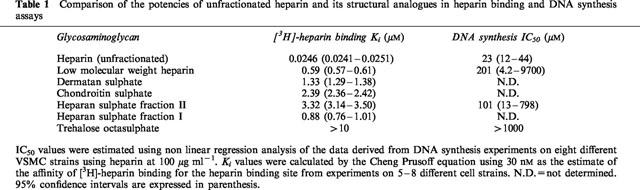

The pharmacology of [3H]-heparin binding was assessed by examining the displacement of [3H]-heparin binding by unlabelled heparin or structurally analogous glycosaminoglycans (over the concentration range 10−9–10−5 M) as shown in Figure 3. Unfractionated heparin, as well as most of the structural analogues competitively inhibited the binding of [3H]-heparin to human VSMC. The Ki values for heparin and the structural analogues (Table 1) were determined by the Cheng Prussof equation using 30 nM as an estimate of the affinity of [3H]-heparin for its binding site. The rank order of affinity for the heparin binding site showed that the unfractionated heparin had the greatest affinity, while the highly sulphated sugar trehalose octasulphate was virtually ineffective at displacing [3H]-heparin from its binding site. With regard to the other glycosaminoglycans, the Ki values showed that [3H]-heparin binding was not significantly affected until the concentration of the structural analogues was over 20 fold greater than that of the ligand.

Figure 3.

(a and b) Pharmacology of [3H]-heparin binding to human VSMC. Displacement assays were performed using [3H]-heparin (10−7 M) in the presence of various analogues (over a range 10−9–10−5 M) during the 30 min period of incubation with ligand. Experiments were conducted on 5–8 different VSMC strains.

Table 1.

Comparison of the potencies of unfractionated heparin and its structural analogues in heparin binding and DNA synthesis assays

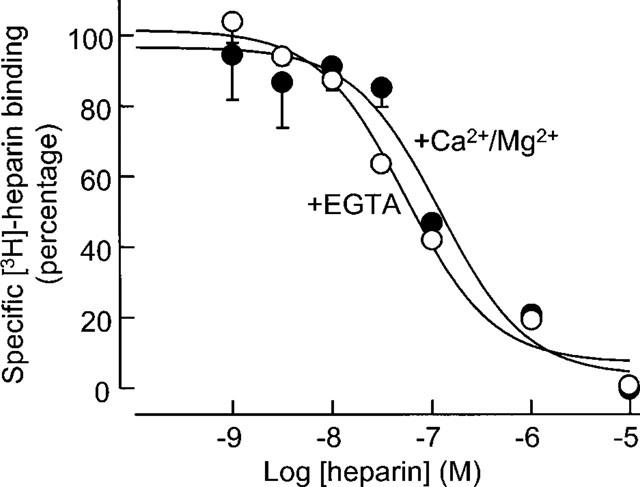

The influence of the divalent cation Ca2+ was examined on the binding of [3H]-heparin by these human VSMC. Radioligand binding assays were conducted using a HEPES-phosphate buffer containing either EGTA (1 mM) or Ca2+ (1 mM) and Mg2+ (1 mM). Chelation of calcium ions had no effect on the level of [3H]-heparin binding under these conditions, indicating that [3H]-heparin binding to cell surface sites in these cells was independent of Ca2+ (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The effect of chelating Ca2+ on the binding of [3H]-heparin to human VSMC. Radioligand binding assays were performed as described either in buffer containing EGTA (1 mM) or CaCl2 (1 mM) and MgCl2 (1 mM). [3H]-heparin (10−7 M) was displaced by cold heparin over a range from 10−9–10−5 M and non-specific counts were subtracted prior to data analysis from three experiments on different VSMC cell strains.

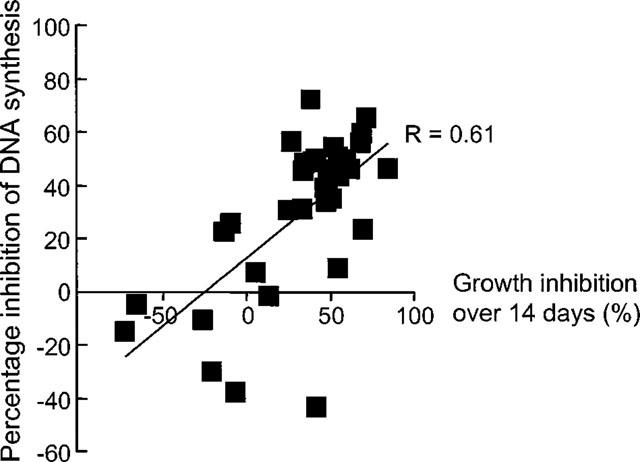

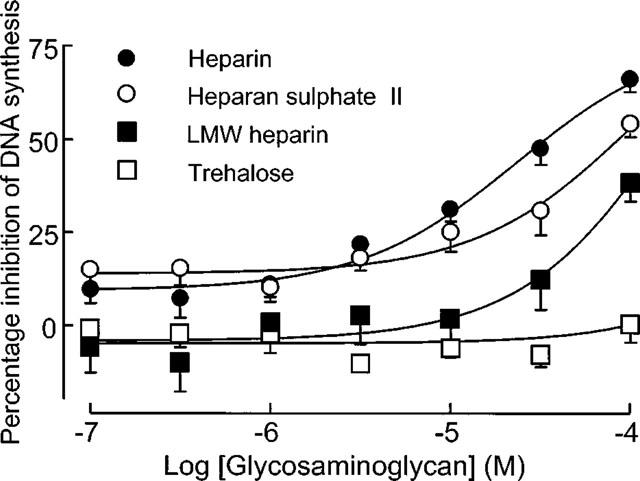

The effect of unfractionated heparin and structural analogues on human VSMC was assessed using DNA synthesis and proliferation assays. In the proliferation assays which were conducted over 14 days, VSMC cultures displayed a range in the sensitivity to the antiproliferative effect of heparin in agreement with our previous findings (Chan et al., 1993a,1993b; Refson et al., 1998). There was a good correlation between the degree of inhibition of FCS-stimulated growth by heparin (100 μg ml−1) at 14 days and its effect on DNA synthesis either at the same concentration (Spearman coefficient r=0.61, 95% confidence interval 0.32–0.80, P<0.0002) as shown in Figure 5 or at 1 mg ml−1 (Spearman coefficient r=0.52, 95% confidence interval 0.20–0.74, P<0.005, data not shown). The effect of heparin and some of the other structural analogues was examined on [3H]-thymidine incorporation in these human saphenous vein-derived VSMC for comparison with the pharmacology determined in the radioligand binding studies. The rank order of potency with regard to the inhibition of DNA synthesis was as follows: heparin>heparan sulphate II>low molecular weight heparin>>trehalose octasulphate (Figure 6). We have also examined the effect of heparin (100 μg ml−1), both heparan sulphate fractions, low molecular weight heparin and trehalose octasulphate on the proliferation of human VSMC over 14 days using a single (molar equivalent) concentration of the analogues and observed that the inhibition of growth is in keeping with the DNA synthesis experiments (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Relationship between the effect of heparin (100 μg ml−1, 7.14 μmol l−1) on human VSMC proliferation over 14 days and DNA synthesis assays. Data points represent the mean±s.e.mean values obtained (for individual cell strains) from DNA synthesis and proliferation experiments which were conducted simultaneously.

Figure 6.

Effect of heparin and structural analogues on DNA synthesis in human saphenous vein-derived VSMC. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data points (mean±s.e.mean, n=8) represent the percentage inhibition of DNA synthesis with respect to 15% FCS.

Discussion

In this investigation we have characterized the binding of [3H]-heparin to human VSMC grown from explant cultures of saphenous vein and compared the pharmacology of binding with the ability of structural analogues to inhibit DNA synthesis. Ligand binding studies revealed that [3H]-heparin bound to a single class of heparin binding sites in a specific, time and concentration-dependent manner and did not require the presence of calcium ions. The ligand-receptor interaction was both saturable and reversible suggesting that it occurred on the cell surface either to an integral cell membrane protein or extracellular matrix protein tightly associated with the cell surface.

In this study the estimated KD for [3H]-heparin binding from saturation and kinetic studies ranged between 30–120 nM. A similar affinity (31 nM) was estimated for unlabelled unfractionated heparin from our displacement studies. Previous reports have defined specific high affinity, protease sensitive binding sites in rat VSMC (≈105 sites cell−1, KD≈1 nM) (Castellot et al., 1985; Resink et al., 1989; Letourneur et al., 1995a) whereas one study with human monocytes identified 1.9×106 heparin binding sites cell−1 with a KD of 190 nM (Leung et al., 1989). In view of the differences in Bmax and KD, it cannot be assumed that these represent the same site as characterized in this study.

Heparin has been reported to bind to VSMC and subsequently undergo internalization at 37°C (Castellot et al., 1985; Sing et al., 1993). Once internalized, it has been localized to endocytic vesicles close to the nucleus and undergoes rapid degradation before ultimately being cleared from cells (Castellot et al., 1985; Barzu et al., 1987). There is some controversy regarding the entry of heparin into the nucleus. For example, there are reports of the nuclear accumulation of heparin fragments (Busch et al., 1992) and fluoresceinamine-labelled heparin (Sing et al., 1993) while more recent reports have failed either to detect heparin in the nucleus using confocal microscopy (Barzu et al., 1996) or an action on the AP-1 transcription factor (Watanabe et al., 1993; Au et al., 1994).

Heparin binding to VSMC appears to be a prerequisite for its growth inhibitory action (Resink et al., 1989; Edwards & Wagner, 1992; Barzu et al., 1994). In VSMC grown from spontaneously hypertensive rats the number of heparin binding sites was reduced and this was accompanied by a reduced sensitivity to growth inhibition by heparin relative to cells from the normotensive Wistar Kyoto counterparts (Resink et al., 1989). Similarly, the resistance to growth inhibition by heparin in rat VSMC (induced by treatment with 200 μg ml−1 heparin between passages 2–10) was characterized both by a 10 fold reduction in the number of binding sites and a reduced intracellular uptake of FITC-heparin (Barzu et al., 1994). Furthermore, this loss of sensitivity to the antiproliferative action of heparin and its analogues was irreversible after further growth of the rat VSMC for two passages in heparin-free medium (Barzu et al., 1994). By contrast, San Antonio et al. (1993) and Letourneur et al. (1995a) who also employed heparin-resistant rat VSMC phenotypes generated by continuous growth of cells with 200 μg ml−1 heparin did not observe this relationship as both the heparin-resistant and sensitive VSMC bound and internalized similar amounts of heparin.

In human VSMC our group was the first to describe the phenomenon of heparin resistance, i.e. the lack of growth inhibition by heparin (Chan et al., 1993b). Heparin resistance in these human VSMC is associated with a reduction in the density of heparin binding sites compared to sensitive cells (Refson et al., 1998). Furthermore, there is a good correlation between the amount of [3H]-heparin binding and the antiproliferative effect of unfractionated heparin in these human VSMC (Refson et al., 1998). The relationship between [3H]-heparin binding at 4°C and its antiproliferative action has been examined by several groups. In VSMC grown from the spontaneously hypertensive rats, Resink et al. (1989) observed a 50% reduction in the density of heparin binding sites compared to cells from control normotensive rats. In heparin-resistant rat VSMC induced by pharmacological selection, Barzu et al. (1994) identified two classes of heparin binding site, but notably there was a 10 fold reduction in the number of both classes of sites in the heparin-resistant cells. Letourneur et al. (1995a) reported a similar KD for heparin binding in both heparin-sensitive and resistant rat VSMC, but observed a greater density of binding sites on the heparin-sensitive cells. Another report, however, failed to show any significant difference between either the number of heparin binding sites or the KD in human VSMC grown from aorta and saphenous vein which were inhibited and stimulated respectively by heparin in DNA synthesis assays (Stohr et al., 1995).

Comparison of the affinities for heparin, heparan sulphate fraction II, low molecular weight heparin and trehalose octasulphate in the ligand binding studies with their potencies as inhibitors of DNA synthesis shows marked differences with unfractionated and low molecular weight heparin being several hundred fold more potent in binding than DNA synthesis assays. Although the binding assays were conducted at 4°C and the DNA synthesis assays at 37°C, it seems unlikely that this difference could account for such marked discrepancies in potency, particularly as binding affinity is generally increased at higher temperature. Similarly, the rank order of potency shows differences between the two assays most notably for the low molecular weight heparin and heparan sulphate II fractions. At 37°C, the binding of heparin is followed by internalization (Castellot et al., 1985) and its subsequent degradation (Letourneur et al., 1995a,1995b). The disparity between the affinity of heparin and its inhibitory effect on DNA synthesis has also been reported by Letourneur et al. (1995a) and may be due to differences either in the internalization and/or metabolism of the glycosaminoglycan which have not been examined in this study.

In summary, the binding of [3H]-heparin to human VSMC occurs through a single class of sites in a specific, saturable, reversible, time and concentration-dependent manner and this was unaffected by the removal of calcium ions. The rank order of potency for heparin and structural analogues in [3H]-heparin binding studies deviates from their actions on DNA synthesis. Our data appears to argue against a simple relationship between cell-associated heparin/analogue binding and the inhibition of DNA synthesis and suggest that internalization and/or metabolism of glycosaminoglycans may also determine their inhibitory actions on DNA synthesis.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Karen Gallagher for expert technical assistance. We should like to thank the Institut de Recherches Internationales Servier for financial support and the surgeons and theatre staff at St. Mary's Hospital for providing the vascular tissues for this investigation.

Abbreviations

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modification of Eagle's medium

- FCS

foetal calf serum

- HSI

heparin sulphate fraction I

- HSII

heparan sulphate fraction II

- LMW

low molecular weight

- PBS-A

Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cell

References

- AU Y.P., DOBROWOLSKA G., MORRIS D.R., CLOWES A.W. Heparin decreases activator protein-1 binding to DNA in part by posttranslational modification of Jun B. Circ. Res. 1994;75:15–22. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AU Y.P., KENAGY R.D., CLOWES A.W. Heparin selectively inhibits the transcription of tissue-type plasminogen activator in primate arterial smooth muscle cells during mitogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1992a;267:3438–3444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AU Y.P., MONTGOMERY K.F., CLOWES A.W. Heparin inhibits collagenase gene expression mediated by phorbol ester-responsive element in primate arterial smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 1992b;70:1062–1069. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.5.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARZU T., HERBERT J.M., DESMOULIERE A., CARAYON P., PASCAL M. Characterization of rat aortic smooth muscle cells resistant to the antiproliferative activity of heparin following long-term heparin treatment. J. Cell. Physiol. 1994;160:239–248. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARZU T., PASCAL M., MAMAN M., ROQUE C., LAFONT F., ROUSSELET A. Entry and distribution of fluorescent antiproliferative heparin derivatives into rat vascular smooth muscle cells: comparison between heparin-sensitive and heparin-resistant cultures. J. Cell. Physiol. 1996;167:8–21. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199604)167:1<8::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARZU T., VAN RIJN J.L., PETITOU M., TOBELEM G., CAEN J.P. Heparin degradation in the endothelial cells. Thromb. Res. 1987;47:601–609. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(87)90365-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUSCH S.J., MARTIN G.A., BARNHART R.L., MANO M., CARDIN A.D., JACKSON R.L. Trans-repressor activity of nuclear glycosaminoglycans on Fos and Jun/AP-1 oncoprotein-mediated transcription. J. Cell. Biol. 1992;116:31–42. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAPLICE N.M., WEST M.J., CAMPBELL G.R., CAMPBELL J. Inhibition of human vascular smooth muscle cell growth by heparin. Lancet. 1994;344:97–98. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASTELLOT J.J., PUKAC L.A., CALEB B.L., WRIGHT T.C., KARNOVSKY M.J. Heparin selectively inhibits a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism of cell cycle progression in calf aortic smooth muscle cells. J. Cell. Biol. 1989;109:3147–3155. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASTELLOT J.J., WONG K., HERMAN B., HOOVER R.L., ALBERTINI D.F., WRIGHT T.C., CALEB B.L., KARNOVSKY M.J. Binding and internalization of heparin by vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1985;124:13–20. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041240104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASU B., JOHNSON E.A., MANTOVANI M., MULLOY B., ORESTE P., PESCADOR R., PRINO G., TORRI G., ZOPPETTI G. Correlation between structure, fat-clearing and anticoagulant properties of heparins and heparan sulphates. Arzneimittelforschung. 1983;33:135–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAN P., MILL S., MULLOY B., KAKKAR V., DEMOLIOU MASON C. Heparin inhibition of human vascular smooth muscle cell hyperplasia. Int. Angiol. 1992;11:261–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAN P., MUNRO E., PATEL M., BETTERIDGE L., SCHACHTER M., SEVER P., WOLFE J. Cellular biology of human intimal hyperplastic stenosis. Eur. J. Vasc. Surg. 1993a;7:129–135. doi: 10.1016/s0950-821x(05)80752-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAN P., PATEL M., BETTERIDGE L., MUNRO E., SCHACHTER M., WOLFE J., SEVER P. Abnormal growth regulation of vascular smooth muscle cells by heparin in patients with restenosis. Lancet. 1993b;341:341–342. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENG Y., PRUSOFF W.H. Relationship between the inhibition constant (Ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLOWES A.W., CLOWES M.M., KIRKMAN T.R., JACKSON C.L., AU Y.P., KENAGY R. Heparin inhibits the expression of tissue-type plasminogen activator by smooth muscle cells in injured rat carotid artery. Circ. Res. 1992;70:1128–1136. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.6.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLOWES A.W., KARNOWSKY M.J. Suppression by heparin of smooth muscle cell proliferation in injured arteries. Nature. 1977;265:625–626. doi: 10.1038/265625a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLOWES A.W., REIDY M.A. Prevention of stenosis after vascular reconstruction: pharmacologic control of intimal hyperplasia – a review. J. Vasc. Surg. 1991;13:885–891. doi: 10.1067/mva.1991.27929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DELMOLINO L.M., CASTELLOT J.J. Heparin suppresses sgk, an early response gene in proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1997;173:371–379. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199712)173:3<371::AID-JCP9>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDWARDS I.J., WAGNER W.D. Cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan of arterial smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Pathol. 1992;140:193–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAGER G., CAMEJO G., BONDJERS G. Heparin-like glycosaminoglycans influence growth and phenotype of human arterial smooth muscle cells in vitro. I. Evidence for reversible binding and inactivation of the platelet-derived growth factor by heparin. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. 1992;28A:168–175. doi: 10.1007/BF02631087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOOVER R.L., ROSENBERG R., HAERING W., KARNOVSKY M.J. Inhibition of rat arterial smooth muscle cell proliferation by heparin. II. In vitro studies. Circ. Res. 1980;47:578–583. doi: 10.1161/01.res.47.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON E.A., MULLOY B. The molecular-weight range of mucosal-heparin preparations. Carbohydr. Res. 1976;51:119–127. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)84041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KENAGY R.D., NIKKARI S.T., WELGUS H.G., CLOWES A.W. Heparin inhibits the induction of three matrix metalloproteinases (stromelysin, 92-kD gelatinase, and collagenase) in primate arterial smooth muscle cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1994;93:1987–1993. doi: 10.1172/JCI117191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LETOURNEUR D., CALEB B.L., CASTELLOT J.J. Heparin binding, internalization, and metabolism in vascular smooth muscle cells: I. Upregulation of heparin binding correlates with antiproliferative activity. J. Cell. Physiol. 1995a;165:676–686. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041650327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LETOURNEUR D., CALEB B.L., CASTELLOT J.J. Heparin binding, internalization, and metabolism in vascular smooth muscle cells: II. Degradation and secretion in sensitive and resistant cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1995b;165:687–695. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041650328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEUNG L., SAIGO K., GRANT D. Heparin binds to human monocytes and modulates their procoagulant activities and secretory phenotypes. Effects of histidine-rich glycoprotein. Blood. 1989;73:177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIBBY P., O'BRIEN K.V. Culture of quiescent arterial smooth muscle cells in a defined serum-free medium. J. Cell. Physiol. 1983;115:217–223. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041150217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDNER V., OLSON N.E., CLOWES A.W., REIDY M.A. Inhibition of smooth muscle cell proliferation in injured rat arteries. Interaction of heparin with basic fibroblast growth factor. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;90:2044–2049. doi: 10.1172/JCI116085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAJACK R.A., CLOWES A.W. Inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell migration by heparin-like glycosaminoglycans. J. Cell. Physiol. 1984;118:253–256. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041180306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAJACK R.A., COOK S.C., BORNSTEIN P. Platelet-derived growth factor and heparin-like glycosaminoglycans regulate thrombospondin synthesis and deposition in the matrix by smooth muscle cells. J. Cell. Biol. 1985;101:1059–1070. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.3.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCAFFREY T.A., FALCONE D.J., BRAYTON C.F., AGARWAL L.A., WELT F.G., WEKSLER B.B. Transforming growth factor-beta activity is potentiated by heparin via dissociation of the transforming growth factor-beta/alpha 2-macroglobulin inactive complex. J. Cell. Biol. 1989;109:441–448. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULLOY B., GEE C., WHEELER S., WAIT R., THOMAS S., GRAY E., BARROWCLIFFE T.W. Molecular weight measurements of low molecular weight heparins by gel permeation chromatography. Thromb. Haemostas. 1997;77:668–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUNRO E., CHAN P., PATEL M., BETTERIDGE L., GALLAGHER K., SCHACHTER M., SEVER P., WOLFE J. Consistent responses of the human vascular smooth muscle cell in culture: implications for restenosis. J. Vasc. Surg. 1994;20:482–487. doi: 10.1016/0741-5214(94)90149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OTTLINGER M.E., PUKAC L.A., KARNOVSKY M.J. Heparin inhibits mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in intact rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:19173–19176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATEL M.K., BETTERIDGE L.J., HUGHES A.D., CLUNN G.F., SCHACHTER M., SHAW R.J., SEVER P.S. Effect of angiotensin II on the expression of the early growth response gene c-fos and DNA synthesis in human vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Hypertens. 1996;14:341–347. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199603000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATEL M.K., LYMN J.S., CLUNN G.F., HUGHES A.D. Thrombospondin-1 is a potent mitogen and chemoattractant for human vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1997;17:2107–2114. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.10.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUKAC L.A., OTTLINGER M.E., KARNOVSKY M.J. Heparin suppresses specific second messenger pathways for protooncogene expression in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:3707–3711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REFSON J.S., SCHACHTER M., PATEL M.K., HUGHES A.D., MUNRO E., CHAN P., WOLFE J.H., SEVER P.S. Vein graft stenosis and the heparin responsiveness of human vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 1998;97:2506–2510. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.25.2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REILLY C.F., KINDY M.S., BROWN K.E., ROSENBERG R.D., SONENSHEIN G.E. Heparin prevents vascular smooth muscle cell progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:6990–6995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RESINK T.J., SCOTT BURDEN T., BAUR U., BURGIN M., BUHLER F.R. Decreased susceptibility of cultured smooth muscle cells from SHR rats to growth inhibition by heparin. J. Cell. Physiol. 1989;138:137–144. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041380119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAN ANTONIO J.D., SLOVER J., LAWLER J., KARNOVSKY M.J., LANDER A.D. Specificity in the interactions of extracellular matrix proteins with subpopulations of the glycosaminoglycan heparin. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4746–4755. doi: 10.1021/bi00069a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SING J.P., WIERNICKI T.R., GUPTA S.K. Role of serine/threonine kinase casein kinase-II in the vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and inhibition by heparin. Drug Dev. Res. 1993;29:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- SKALLI O., VANDERKERCHOVE J., GABBIANI G. Actin-isoform pattern as a marker of normal or pathological smooth muscle and fibroblastic tissues. Differentiation. 1987;33:232–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1987.tb01562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNOW A.D., BOLENDER R.P., WIGHT T.N., CLOWES A.W. Heparin modulates the composition of the extracellular matrix domain surrounding arterial smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Pathol. 1990;137:313–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STOHR S., MEYER T., SMOLENSKI A., KREUZER H., BUCHWALD A.B. Effects of heparin on aortic versus venous smooth muscle cells: similar binding with different rates of [3H]thymidine incorporation. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1995;25:782–788. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199505000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATANABE J., MURANISHI H., HABA M., YUASA H. Uptake of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-fractionated heparin by rat parenchymal hepatocytes in primary culture. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1993;16:939–941. doi: 10.1248/bpb.16.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]