Abstract

Mutations of specific amino acids were introduced in transmembrane domains (TM) of GABAA receptor α2, β1 and γ2L subunits. The effects of these mutations on the action of ethanol were studied using the Xenopus oocyte expression system and two-electrode voltage-clamp recording techniques.

Mutant α2 subunits containing S270I (TM2) or A291W (TM3) made the receptor more sensitive to GABA, as compared to wild-type α2β1γ2L receptor. The mutation S265I (TM2) of β1 and S280I (TM2) or S301W (TM3) in γ2L subunits did not alter apparent affinity of the receptor for GABA. M286W (TM3) in the β1 subunit resulted in a receptor that was tonically open.

Using an EC5 concentration of GABA, the function of the wild-type receptor with α2β1γ2L subunits was potentiated by ethanol (50–200 mM). The mutations in TM2 or TM3 of the α2 subunit diminished the potentiation by ethanol. The action of ethanol was also eliminated with a mutation in the TM2 site of the β1 subunit. Ethanol produced significant inhibition of GABA responses in receptors containing the combination of α2 and β1 TM2 mutants with a wild-type γ2L subunit. A small but significant reduction in the potentiation by ethanol was observed with γ2L TM2 and/or TM3 mutants.

From these results, we suggest that in heteromeric GABAA receptors composed of the α, β and γ subunits, ethanol may bind in a cavity formed by TM2 and TM3, and that binding to the α or β subunit may be more critical than the γ subunit.

Keywords: GABAA receptor, mutation, Xenopus oocytes, ethanol

Introduction

Ethanol is one of the oldest and most widely consumed drugs, and has many behavioural effects, some of which are shared with sedative, hypnotic and anaesthetic agents. It is likely that sites for ethanol's action in brain include several neurotransmitter receptors and ion channels (Deitrich et al., 1989; Harris et al., 1995). One ligand-gated ion channel of interest as a target for ethanol, as well as sedative, hypnotic and anaesthetic drugs, is the γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor. Recent studies using techniques such as mutagenesis and heterologous expression systems have made it possible to investigate the cellular and molecular mechanisms of the action of ethanol on GABAA receptors (Mihic & Harris, 1996).

The GABAA receptor/chloride channel complex is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter receptor in the mammalian brain. It is a member of the ligand-gated ion channel superfamily, which includes glycine, GABAC, 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 (5-HT3) and nicotinic acetylcholine (nACh) receptors (Ortells & Lunt, 1995). Five classes of GABAA receptor subunits (α1–6, β1–4, γ1–4, δ, ε) have been cloned to date (Whiting et al., 1992). Because GABAA receptors expressed in vitro without the γ subunit are sensitive to general anaesthetics and n-alcohols (Levitan et al., 1988; Pritchett et al., 1989; Harrison et al., 1993; Mihic et al., 1994), the α and β subunits are likely target proteins for anaesthetic agents. Recent studies demonstrated that mutation of specific amino acids in the transmembrane domains (TM) of the α or β subunit of GABAA receptor can eliminate the action of ethanol, enflurane and isoflurane (Mihic et al., 1997; Krasowski et al., 1998) without abolishing the response to GABA. These results suggest that the receptors might have specific regions and conformations for the action of alcohols and anaesthetics.

However, only α and β subunits were used in our previous mutation studies. Most GABAA receptors in brain are composed of α, β and γ subunits with the consensus stoichiometry being α2β2γ1 (Chang et al., 1996; Tretter et al., 1997), and it was demonstrated that low concentrations of ethanol appear to require the presence of a γ subunit (Wafford et al., 1991; Wafford & Whiting, 1992; Harris et al., 1997). Therefore, these findings raise several questions: how do the mutations in α or β subunits affect the action of alcohols when GABAA receptors are composed of α, β and γ subunits? Are there any effects of mutations in the corresponding regions of the γ subunit on the action of alcohols? Mihic et al. (1997) tested only a single, high concentration of alcohol: can mutations in α, β or γ subunits differentially affect the action of low and high concentrations of alcohols?

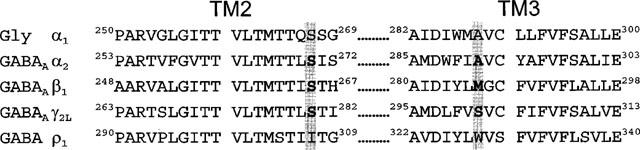

To investigate the importance of the γ subunit, we expressed mutant α2 or β1 subunits together with the γ2L subunit in Xenopus oocytes and studied effects of a range of concentrations of ethanol. Moreover, we prepared mutant γ2L subunits and investigated the effect of these mutations on actions of ethanol. Previous studies of chimeric and mutant receptors identified one amino acid residue in TM2 and one in TM3 that account for the difference in ethanol action on GABA ρ1 (GABAC) receptor function (inhibition) as compared to glycine receptors (enhancement) (Mihic et al., 1997). The critical residue in TM2 is serine in glycine α1, GABAA receptor α2, α1, β1 and γ2 subunits, but is isoleucine in the GABA ρ1 receptor subunit (Figure 1). The TM3 residue is alanine in glycine α1, GABAA receptor α2, β1 and γ2 subunits, but tryptophan in the GABA ρ1 receptor subunit (Figure 1). Because mutation of the TM2 serine to isoleucine markedly inhibits the action of ethanol on receptors composed of glycine α1 or GABAA receptor α1 and β1 subunits (Mihic et al., 1997), we also mutated the homologous serine residue in TM2 of GABAA receptor γ2L subunit to isoleucine for the present studies. Similarly, mutation of alanine to tryptophan in GABAA receptor α2 subunit prevents action of ethanol and therefore the homologous serine residue in the γ2L subunit was mutated to tryptophan for our current studies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequence alignment of TM2 and TM3 from human glycine α1, GABAA α2, β1, γ2L, and GABA ρ1 receptor subunits. The amino acids investigated in the present study are Ser270 and Ala291 in GABAA receptor α2, Ser265 and Met286 in β1 and Ser280 and Ser301 in γ2L subunits (shown as bold letters). The amino acids in TM2 were all mutated to Ile and those in TM3 to Trp (see Methods).

Methods

Adult Xenopus laevis female frogs were obtained from Xenopus I (Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A.); GABA from Research Biochemicals International (Natick, MA, U.S.A.); dimethylsulphoxide, collagenase type 1A, picrotoxin and flunitrazepam from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.); Ethanol from Aaper Alcohol and Chemical Co. (Shelbyville, KY, U.S.A.). All other chemicals used were of reagent grade.

Mutations in cDNAs of human GABAA receptor α2 (S270I, A291W) and β1 (S265I, M286W) subunits were described previously (Krasowski et al., 1998). The S280I and S301W mutations in the γ2L subunits were introduced by use of the QuikChange Site-directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.). The cDNAs of wild-type or mutant receptor subunits were subcloned into the pCIS2 or modified (Wick et al., 1998) pBK-CMV (Stratagene) vectors. All point mutations were verified by double-stranded DNA sequencing.

Xenopus oocytes were isolated and injected with cDNAs (1.5 ng per 30 nl), and two-electrode voltage-clamp recordings were performed as described previously (Mihic et al., 1994; Harris et al., 1997). GABA was applied for 20–30 s and the maximum (peak) current was used as a measure of drug response. For GABA concentration-response curves, we applied 0.03 μM–1 mM GABA solutions for a single oocyte with an interval of 5 min, or 15 min when desensitization was observed. We tested the capacity of ethanol to enhance the effect of administration of GABA concentration that produced 5% of the maximal effect (EC5) of GABA, because there is a dependence on the GABA concentration with greater potentiation by ethanol being seen at the lower GABA concentrations (Mihic et al., 1994). This EC5 was determined individually for each oocyte. We used 1 mM GABA to produce a maximal current. Oocytes were perfused with ethanol for 2 min before coapplication of GABA, to allow for complete equilibration of the oocytes with ethanol. In all cases, a 15–20 min washout period was allowed following application of the ethanol/GABA solutions. The solutions were freshly prepared immediately before use. Each data point represents a mean from 3–38 oocytes obtained from at least two different frogs. Across all the potentiation experiments for wild-type and mutant receptors reported here, the actual percentage of maximal GABA response for the test concentrations used here were: α2β1γ2L wild-type (4.9±0.1%, total 58 experiments), α2(S270I)β1γ2L (5.0±0.2%, 20 experiments), α2(A291W)β1γ2L (5.0±0.1%, 24 experiments), α2β1(S265I)γ2L (5.1±0.2%, 14 experiments), α2(S270I)β1(S265I)γ2L (5.0±0.2%, 9 experiments), α2β1γ2L(S280I) (5.0±0.3%, 14 experiments), α2β1γ2L (S301W) (5.1±0.1%, 15 experiments) and α2β1γ2L(S280I/S301W) (5.0±0.1%, 22 experiments).

All values are presented throughout as mean±standard error of the mean (s.e.mean). Statistical analyses were carried out by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni's comparison post hoc test, paired or unpaired, two-tailed t-test using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). Curve fitting and estimation of EC50 values for concentration-response curves were also performed using this software.

Results

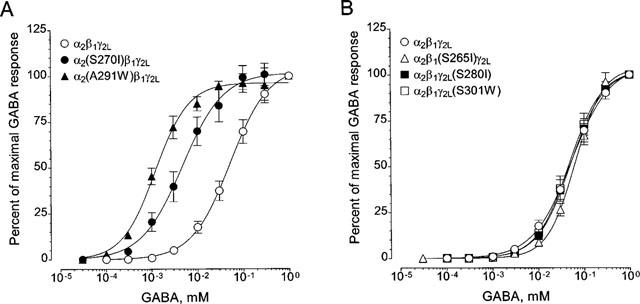

TM2 or TM3 mutations (S270I or A291W) in the α2 subunit made the receptor 10 or 30 times more sensitive to GABA, respectively, as compared with wild-type receptors composed of human α2β1γ2L subunits (Figure 2A). On the other hand, mutation of S265I in the β1 subunit did not alter the sensitivity of the receptor to GABA (Figure 2B). Moreover, in the γ2L subunit, neither the mutation of S280I nor S301W affected the apparent affinity for GABA (Figure 2B). A summary of the EC50 concentrations of GABA and the Hill slope for wild-type and mutant GABAA receptors is shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

GABA concentration-response curves for wild-type and mutant GABAA receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. The curves for mutant α2(S270I)β1γ2L and α2(A291W)β1γ2L are shown in (A) and mutant α2β1(S265I)γ2L, α2β1γ2L(S280I) and α2β1γ2L(S301W) are in (B) The curve for wild-type α2β1γ2L are shown in both (A) and (B). Nonlinear regression analysis of the curves was performed as described in ‘Methods', and the results shown in Table 1. Values are presented as mean±s.e.mean from 4–6 oocytes. In some cases, the error bars are smaller than the points.

Table 1.

GABA EC50s, Hill slopes and maximal responses for wild-type and mutant GABAA receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes

Coexpression of mutant β1(M286W) with wild-type α2 and γ2L subunits produced a receptor with unusual gating properties. An outward current was obtained from the application of picrotoxin to oocytes expressing mutant α2β1(M286W)γ2L receptors, i.e. in the direction opposite to that of the normal GABA-induced current (data not shown). Because picrotoxin closes GABAA receptor chloride channels, this result indicates that these mutant receptors formed tonically open channels. This subunit combination was not studied further.

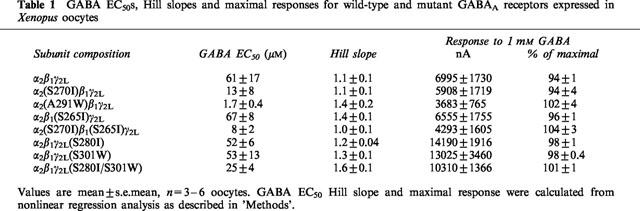

We next compared the effects of ethanol on wild-type and mutant GABAA receptors. As shown in Figure 3A–C, ethanol produced up to 90% potentiation of the GABA-induced current for wild-type α2β1γ2L GABAA receptors expressed in oocytes. Using an EC5 concentration of GABA, we obtained 21±1% potentiation by 50 mM ethanol, 48±2% potentiation by 100 mM ethanol and 91±3% potentiation by 200 mM ethanol. Coexpression of mutant α2(S270I) or α2(A291W) with wild-type β1 and γ2L subunits diminished the potentiation by all concentrations of ethanol (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

The effects of mutations in TM2 and TM3 in individual GABAA receptor subunits on the action of ethanol in Xenopus oocytes. (A) Oocytes expressing wild-type α2β1γ2L, mutant α2(S270I)β1γ2L or α2(A291W)β1γ2L receptors were preincubated with ethanol (50, 100 and 200 mM) for 2 min before being coapplied with EC5 of GABA for 20–30 s. Same symbols as those in Figure 2 are used for presenting the values for each combination of receptor. (B) The values of potentiation are shown for mutant α2β1(S265I)γ2L and α2(S270I)β1(S265I)γ2L receptor. The values for wild-type α2β1γ2L are from (A). (C) The values of potentiation are shown for mutant α2β1γ2L(S280I) and α2β1γ2L(S301W) receptor. The values for wild-type α2β1γ2L are from (A). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001, compared to wild-type α2β1γ2L using ANOVA with Bonferroni's comparison post hoc test. All values are presented as mean±s.e.mean from 5–24 oocytes. In some cases, the error bars are smaller than the points.

There was also a decrease in ethanol potentiation with mutant α2β1(S265I)γ2L receptors (Figure 3B), although this mutation did not affect the apparent affinity of the receptors for GABA (Figure 2B). Furthermore, receptors formed by this mutant β1(S265I) subunit with the mutant α2(S270I) and wild-type γ2L subunits showed no potentiation by ethanol and even displayed significant inhibition (P<0.01, compared to the response produced by GABA EC5 using paired, two-tailed t-test) by 200 mM ethanol (Figure 3B). This α2(S270I)β1(S265I)γ2L receptor showed sensitivity to GABA that was similar to the mutant α2(S270I)β1γ2L receptor (Table 1). We did not examine the pharmacology of the mutant α2β1(M286W)γ2L receptor because of its unusual gating properties, and because oocytes in which these mutant receptors were expressed did not show stable currents or GABA responses.

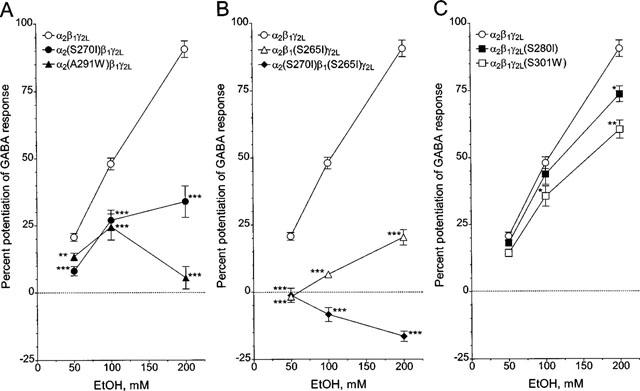

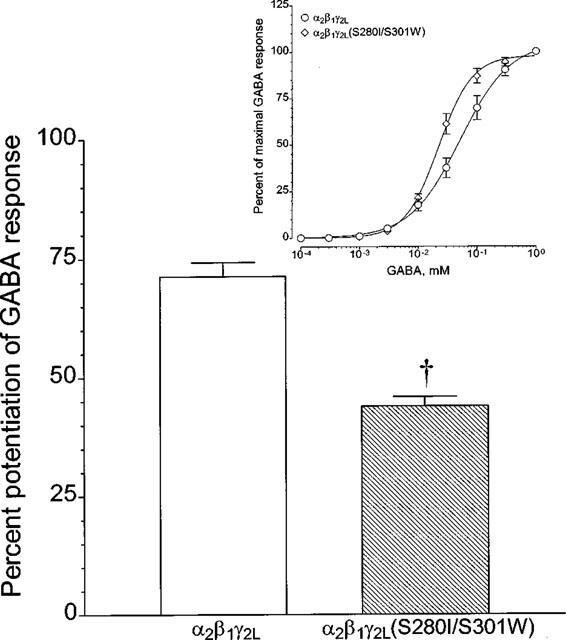

Mutant α2β1γ2L(S280I) or α2β1γ2L(S301W) receptors closely resembled wild-type GABAA receptors (Figure 3C). Therefore, we next made a double mutation of S280I/S301W in the γ2L subunit. For the GABA concentration-response curve, a small change was observed with the mutant α2β1γ2L(S280I/S301W) receptors (Figure 4, inset); nonlinear regression analysis yielded a slightly lower EC50 for GABA (Table 1). This double mutation also significantly reduced potentiation by 200 mM ethanol (Figure 4, bar graph); the decreased potentiation produced by this mutation was similar to that produced by a single mutation, S301W. Potentiation by 200 mM ethanol for the wild-type in this experiment, was somewhat lower (70±3%) than that shown in Figure 3, apparently due to variability among batches of oocytes. We also examined the potentiation produced by 1 μM flunitrazepam, but there was no difference in flunitrazepam action between α2β1γ2L and α2β1γ2L(S280I/S301W) (data not shown).

Figure 4.

The effect of a double mutation in TM2/TM3 of γ2L subunit on the potentiation by ethanol. Oocytes expressing wild-type α2β1γ2L or mutant α2β1γ2L(S280I/S301W) receptors were incubated with 200 mM ethanol for 2 min followed by the coapplication with an EC5 of GABA for 20–30 s. Values are presented as mean±s.e.mean from 17–38 oocytes. †P<0.0001, compared to wild-type α2β1γ2L using unpaired, two-tailed t-test. Inset. GABA concentration-response curve for this mutant receptor is shown together with the one for wild-type, which is from Figure 2. Values are presented as mean±s.e.mean from five oocytes and nonlinear regression analysis of those curves was performed as described in ‘Methods' and given in Table 1. In some cases, the error bars are smaller than the points.

Discussion

The aims of the present study were to investigate (i) the effect of mutations in the corresponding regions in TM2 and TM3 of α, β and γ subunits of the GABAA receptor on the potentiation by ethanol; (ii) the effect of mutations in individual GABAA receptor subunits on potentiation by lower as well as high concentrations of ethanol; (iii) the role of the γ subunit for the function of the GABAA receptor in combination with wild-type and/or mutant α and β subunits. Mutation of TM2 or TM3 sites in the γ2L subunit produced a small reduction in the potentiation by ethanol, but had much less effect than did the analogous mutations in α2 and β1 subunits. The double mutation of S280I/S301W in the γ2L subunit also reduced the potentiation by ethanol, but the degree of reduction was similar to that produced the single mutation of S301W at 200 mM ethanol. This double mutation did not affect the potentiation of receptor function by a benzodiazepine, flunitrazepam, the action of which requires the presence of the γ subunit (Pritchett et al., 1989). These results suggest that, for the potentiation by ethanol in the heteromeric GABAA receptor composed of the α2, β1 and γ2L subunits, the amino acids in TM2 and/or TM3 of the α2 and β1 subunits are more important than are those of the γ2L subunit.

Previous studies (Mihic et al., 1997; Ye et al., 1998) tested only 200 mM ethanol, a concentration not likely to be encountered in vivo (Deitrich & Harris, 1996), and we therefore asked whether those mutations also inhibited the action of lower (i.e. sub-anaesthetic) concentrations of ethanol. The effect of mutations on the potentiation by 50 mM ethanol appeared smaller than that by 200 mM ethanol (Figure 3). Therefore, we calculated the ethanol effect on the mutant receptors as a percentage of the wild-type response, using wild-type data obtained from the same batch of oocytes. For all mutations tested, we found that the mutation had a similar effect at 50 or 200 mM ethanol (data not shown). Therefore, we conclude that all mutations affect the potentiation produced by not only a high concentration, but also lower concentrations of ethanol.

The present results suggest that the α2 and β1 subunits of the GABAA receptor are the primary sites for ethanol action, with the γ2L subunit being less influential. The small effect of mutations on the γ2L subunit, as compared to α2 and β1 subunits, in the present study may reflect the suggested stoichiometry of the receptor with two α and β subunits but only a single γ subunit (Chang et al., 1996; Tretter et al., 1997).

Mutations in TM2 or TM3 of the α2 subunit altered the apparent affinity of GABAA receptors for GABA, but the mutation in TM2 of the β1 subunit did not change the sensitivity to GABA. Mutations in neither TM2 nor TM3 in γ2L subunit altered apparent affinity, but a small change in a GABA concentration-response curve was observed in TM2/TM3 double-mutation of γ2L subunit. There is evidence for a GABA-binding site on the α subunit as mutations of Phe64 in the α1 subunit produce marked decreases in the affinity of GABAA receptor agonists and antagonists for the receptor (Sigel et al., 1992), and this residue is photoaffinity-labelled by muscimol (Smith & Olsen, 1994). However, there is also evidence that the N-terminal regions of β subunit contain GABA-binding sites (Amin & Weiss, 1993), and it is possible that GABA binds at an interface between the α and β subunits. The changes in apparent affinity for GABA observed in the present study could be due to effects of the mutations on the binding affinity or on gating. Considering the distance of our mutations from the N-terminal regions that mediate GABA binding, the latter possibility seems most likely.

In summary, we suggest that ethanol binds in a cavity formed by TM2 and TM3 in the GABAA receptor subunits, and that the α2 and β1 subunits may be critical because they contain GABA-binding sites. The γ2L subunit may also be less important than the α2 or β1 subunit, because only a single γ subunit may assemble in the pentameric oligomer. This suggestion of an ethanol binding cavity in GABAA receptors is supported by the recent study demonstrating that mutation of Ile307 and/or Trp328 (equivalent to the TM2 and TM3 residues) in the GABA ρ1 subunit, to smaller amino acid residues (Ser and/or Ala, respectively) increased alcohol cutoff (Wick et al., 1998). Thus, our mutations to bigger residues in GABAA receptor α2 and/or β1 subunits may decrease the size of a cavity, resulting in the elimination of ethanol action. However, we should note that none of the experimental approaches used to date can provide direct, structural evidence for an ethanol binding cavity.

These studies extend previous work on homomeric glycine and GABAC receptors (Mihic et al., 1997; Wick et al., 1998) to heteromeric GABAA receptors coupled of three different subunits. For these three types of ligand-gated ion channels, similar regions of TM2 and TM3, near the extracellular face are critical for alcohol actions. Further work is required to determine if the site of alcohol action is similar in other ligand-gated ion channels. Finally, mutation of an amino acid in TM2 of the β1 subunit does not change the action of GABA, but markedly affects the action of ethanol. Therefore, construction of transgenic mice or ‘knock-in' mice with a mutant β subunit gene should allow us to determine which behavioural actions of ethanol require enhancement of GABAA receptor function in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Paul J. Whiting for providing GABAA receptor subunit cDNAs. We also thank Virginia Bleck and Susan J. Brozowski for technical assistance. This work was supported by funds from the Department of Veterans Affairs, NIH grants AA06399 and GM47818 and the Uehara Memorial Foundation.

Abbreviations

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- TM

transmembrane domains

References

- AMIN J., WEISS D.S. GABAA receptor needs two homologous domains of the β-subunit for activation by GABA but not by pentobarbital. Nature. 1993;366:565–569. doi: 10.1038/366565a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANG Y., WANG R., BAROT S., WEISS D.S. Stoichiometry of a recombinant GABAA receptor. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:5415–5424. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05415.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEITRICH R.A., DUNWIDDIE T.V., HARRIS R.A., ERWIN V.G. Mechanism of action of ethanol: Initial central nervous system actions. Pharmacol. Rev. 1989;41:489–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEITRICH R.A., HARRIS R.A. How much alcohol should I use in my experiments. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 1996;20:1–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARRIS R.A., MIHIC S.J., BROZOWSKI S., HADINGHAM K., WHITING P.J. Ethanol, flunitrazepam, and pentobarbital modulation of GABAA receptors expressed in mammalian cells and Xenopus oocytes. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 1997;21:444–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1997.tb03789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARRIS R.A., MIHIC S.J., DILDY-MAYFIELD J.E., MACHU T.K. Actions of anesthetics on ligand-gated ion channels: role of receptor subunit composition. FASEB J. 1995;9:1454–1462. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.14.7589987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARRISON N.L., KUGLER J.L., JONES M.V., GREENBLATT E.P., PRITCHETT D.B. Positive modulation of human γ- aminobutyric acid type A and glycine receptors by the inhalation anesthetic isoflurane. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993;44:628–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRASOWSKI M.D., KOLTCHINE V.V., RICK C.E., YE Q., FINN S.E., HARRISON N.L. Propofol and other intravenous anesthetics have sites of action on the γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor distinct from that for isoflurane. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:530–538. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.3.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVITAN E.S., BLAIR L.A., DIONNE V.E., BARNARD E.A. Biophysical and pharmacological properties of cloned GABAA receptor subunits expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Neuron. 1988;1:773–781. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIHIC S.J., HARRIS R.A.Alcohol actions at the GABAA receptor/chloride channel complex Pharmacological Effects of Ethanol on the Nervous System 1996Boca Raton: CRC Press, Inc; 51–71.eds. Deitrich, R.A. & Erwin, V.G. pp [Google Scholar]

- MIHIC S.J., WHITING P.J., HARRIS R.A. Anaesthetic concentrations of alcohols potentiate GABAA receptor-mediated currents: lack of subunit specificity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994;268:209–214. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(94)90190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIHIC S.J., YE Q., WICK M.J., KOLTCHINE V.V., KRASOWSKI M.D., FINN S.E., MASCIA M.P., VALENZUELA C.F., HANSON K.K., GREENBLATT E.P., HARRIS R.A., HARRISON N.L. Sites of alcohol and volatile anaesthetic action on GABAA and glycine receptors. Nature. 1997;389:385–389. doi: 10.1038/38738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORTELLS M.O., LUNT G.G. Evolutionary history of the ligand-gated ion channel superfamily of receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:121–127. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93887-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRITCHETT D.B., SONTHEIMER H., SHIVERS B.D., YMER S., KETTENMANN H., SCHOFIELD P.R., SEEBURG P.H. Importance of a novel GABAA receptor subunit for benzodiazepine pharmacology. Nature. 1989;338:582–585. doi: 10.1038/338582a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIGEL E., BAUR R., KELLENBERGER S., MALHERBE P. Point mutations affecting antagonist affinity and agonist dependent gating of GABAA receptor channels. EMBO J. 1992;11:2017–2023. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH G.B., OLSEN R.W. Identification of a [3H]muscimol photoaffinity substrate in the bovine γ-aminobutyric acidA receptor α subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:20380–20387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRETTER V., EHYA N., FUCHS K., SIEGHART W. Stoichiometry and assembly of a recombinant GABAA receptor subtype. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:2728–2737. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02728.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAFFORD K.A., BURNETT D.M., LEIDENHEIMER N.J., BURT D.R., WANG J.B., KOFUJI P., DUNWIDDIE T.V., HARRIS R.A., SIKELA J.M. Ethanol sensitivity of the GABAA receptor expressed in Xenopus oocytes requires 8 amino acids contained in the γ2L subunit. Neuron. 1991;7:27–33. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAFFORD K.A., WHITING P.J. Ethanol potentiation of GABAA receptors requires phosphorylation of the alternatively spliced variant of the γ2 subunit. FEBS lett. 1992;313:113–117. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81424-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITING P.J., MCKERNAN R.M. &, WAFFORD K.A. Structure and pharmacology of vertebrate GABAA receptor subtypes. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 1992;38:95–138. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60525-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WICK M.J., MIHIC S.J., UENO S., MASCIA M.P., TRUDELL J.R., BROZOWSKI S.J., YE Q., HARRISON N.L., HARRIS R.A. Mutations of γ-aminobutyric acid and glycine receptors change alcohol cutoff: Evidence for an alcohol receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:6504–6509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YE Q., KOLTCHINE V.V., MIHIC S.J., MASCIA M.P., WICK M.J., FINN S.E,, , HARRISON N.L., HARRIS R.A. Enhancement of glycine receptor function by ethanol is inversely correlated with molecular volume at position α267. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:3314–3319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]