Abstract

Inhibitors of serotonin reuptake in the central nervous system, such as fluoxetine, may also affect the function of vascular tissues. Thus, we investigated the effect of fluoxetine on the vasomotor responses of isolated, pressurized arterioles of rat gracilis muscle (98±4 μm in diameter at 80 mmHg perfusion pressure).

We have found that increasing concentrations of fluoxetine dilated arterioles up to 155±5 μm with an EC50 of 2.5±0.5×10−6 M.

Removal of the endothelium, application of 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, an inhibitor of aminopyridine sensitive K+ channels), or use of glibenclamide (an inhibitor of ATP-sensitive K+ channels) did not affect the vasodilator response to fluoxetine.

In the presence of 10−6, 2×10−6 or 10−5 M fluoxetine noradrenaline (NA, 10−9–10−5 M) and 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT, 10−9–10−5 M)-induced constrictions were significantly attenuated resulting in concentration-dependent parallel rightward shifts of their dose-response curves (pA2=6.1±0.1 and 6.9±0.1, respectively).

Increasing concentrations of Ca2+ (10−4–3×10−2 M) elicited arteriolar constrictions (up to ∼30%), which were markedly reduced by 2×10−6 M fluoxetine, whereas 10−5 M fluoxetine practically abolished these responses.

In conclusion, fluoxetine elicits substantial dilations of isolated skeletal muscle arterioles, a response which is not mediated by 4-AP- and ATP-sensitive K+ channels or endothelium-derived dilator factors. The findings that fluoxetine had a greater inhibitory effect on Ca2+ elicited constrictions than on responses to NA and 5-HT suggest that fluoxetine may inhibit Ca2+ channel(s) or interfere with the signal transduction by Ca2+ in the vascular smooth muscle cells.

Keywords: Fluoxetine (Prozac), dilatation, endothelium, arteriolar potassium channels, 5-hydroxytryptamine, Ca2+ sensitivity

Introduction

Inhibition of serotonin (5-HT) reuptake in the central nervous system by fluoxetine (Prozac) has been widely used in the treatment of various psychiatric disorders. It is believed that this effect is specific without affecting the function of other tissues. However, several recent studies suggested that fluoxetine may have other effects, apparently not related to the inhibition of neuronal 5-HT reuptake. Fluoxetine was found to be a potent antagonist at muscular and neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (Colunga et al., 1997) and inhibitor of neuronal Na+ (Pancrazio et al., 1998) and voltage-dependent potassium (Tytgat et al., 1997) channels. Furthermore, fluoxetine reduced nitrendipine binding to dihydropyridine-sensitive neuronal L-type Ca2+ channels and attenuated intracellular Ca2+ transients in fura-2 loaded synaptosomes (Stauderman et al., 1992). It has been suggeted that fluoxetine inhibits potassium-induced 5-HT release by decreasing voltage dependent Ca2+-entry into nerve terminals, similar to results obtained with paroxetine, another serotonin reuptake inhibitor (Stauderman et al., 1992). Fluoxetine also inhibited several types of voltage-gated K+ channels in cultured human corneal and lens epithelial cells (Rae et al., 1995).

In isolated rat uterus fluoxetine inhibited the contraction induced by high K+ (Velasco et al., 1997). In smooth muscle cells, low concentrations of fluoxetine (10−7–10−5 M) decreased the delayed rectifier K+ current, whereas at higher concentrations (10−4 M) fluoxetine increased the Ca2+-activated K+ current (Farrugia, 1996).

Interestingly, there is an increasing number of case reports describing atrial fibrillation, bradycardia (Buff et al., 1991; Friedman, 1991; Anderson & Compton, 1997) and syncope (Ellison et al., 1990; McAnally et al., 1992; Cherin et al., 1997; Livshits & Danenberg, 1997; Rich et al., 1998) associated with fluoxetine treatment. Recently a multicenter case-control study has shown that in the elderly the consumption of fluoxetine was significantly associated with an excess risk of syncope and orthostatic hypotension (Cherin et al., 1997). A significant blood pressure lowering effect of fluoxetine was reported in DOCA-hypertensive rats (Fuller et al., 1979). The authors suggested that a central action of fluoxetine on vasomotor centers may be responsible for the reduction of blood pressure, but the possible direct cardiac and/or vascular effects of fluoxetine were not excluded or determined.

Other types of antidepressant agents such as tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants have well documented cardiovascular effects in patients without pre-existing cardiac disease (Glassman, 1984; Burckhardt et al., 1978; Giardina et al., 1979; Vohra et al., 1975; Boehnert & Lovejoy, 1985). One of the most common manifestations of such effects is postural hypotension, arising in part from α-adrenergic blockade (Hayes et al., 1977; Glassman et al., 1979).

The possible underlying mechanisms of cardiovascular effects of fluoxetine, a newer non-tricyclic antidepressant agent known to be a potent and specific inhibitor of serotonin reuptake (SSRI), are not known.

On the basis of these previous findings we hypothesized that fluoxetine may affect the tone of resistance arterioles thereby promoting hypotension. In order to avoid the masking effect of neural and hormonal regulation of peripheral resistance the present study was undertaken to characterize the effect of fluoxetine in arterioles isolated from rat gracilis muscle. Furthermore, we aimed to elucidate the possible role of endothelium, various K+ channels and altered Ca2+ sensitivity in fluoxetine-induced vasomotor responses.

Methods

Isolation of arterioles

Experiments were conducted on isolated arterioles (∼100 μm active and ∼150 μm passive diameter at 80 mmHg) of male Wistar rats (weighing 140–180 g) gracilis muscle, as described previously (Koller et al., 1995a; Sun et al., 1996). Briefly, rats were anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg kg−1). The gracilis muscle was isolated from surrounding tissues, dissected out and placed in a silicone-lined Petri dish containing cold (0–4°C) physiological salt (PS) solution composed of (in mM): NaCl 110, KCl 5.0, CaCl2 2.5, MgSO4 1.0, KH2PO4 1.0, dextrose 10.0 and NaHCO 24.0 and was equilibrated with a gas mixture of 10% O2 and 5% CO2, balanced with nitrogen, at pH 7.4. Using microsurgical instruments and an operating microscope a segment, 1.5–2 mm in length of an arteriole running intramuscularly was isolated, and transferred to an organ chamber containing two glass micropipettes filled with PS solution. From a reservoir the vessel chamber (15 ml) was continuously supplied with PS solution at a rate of 40 ml min−1. After the vessel had been mounted on the proximal micropipette and was secured with sutures, the perfusion pressure was raised to 20 mmHg to clear the clotted blood from the lumen. Then the other end of the vessel was mounted on the distal pipette. Both micropipettes were connected with silicone tubing to an adjustable PS solution-reservoir. Pressure on both sides was measured by an electromanometer. The perfusion pressure was slowly (approximately over 1 min) increased to 80 mmHg. The temperature was set at 37°C by a temperature controller (Grant Instruments, Great Britain) and the vessel was allowed to equilibrate for approximately 1 h.

Experimental protocols

Only those vessels which developed spontaneous tone in response to perfusion pressure were used and thus no vasoactive agent was added to the PS solution to establish arteriolar tone. After the equilibration period the diameter of arterioles was measured at 80 mmHg perfusion pressure under zero-flow conditions by videomicroscopy as described previously (Koller et al., 1995a; Koller & Huang, 1997; Sun et al., 1996). At the conclusion of each experiment, the bath solution was changed to a Ca2+ free PS solution, which contained sodium nitroprusside (SNP, 10−4 M) and EGTA (ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, 1.0 mM). The vessel was incubated for 10 min, and the maximum passive diameter at 80 mmHg pressure was obtained (passive diameter). The diameter was measured with a microangiometer and recorded with a chart recorder.

Responses to increasing concentration of fluoxetine (10−7–10−5 M) were obtained before and after endothelium removal or in the presence of 10−6 M glibenclamide (an inhibitor of ATP-dependent K+-channels, Castle et al., 1989) or 10−5 M 4-aminopyridine (an inhibitor of aminopyridine sensitive K+-channels, Castle et al., 1989). The endothelium of arterioles was removed by perfusion of the vessel with air for ∼1 min at a perfusion pressure of 20 mmHg (Koller et al., 1995a). The arteriole was then perfused with PS solution to clear the debris. Then the perfusion pressure was raised to 80 mmHg for 30 min to establish a stable tone. The efficacy of endothelial denudation was ascertained by arteriolar responses to acetylcholine (ACh, 10−7 M, an endothelium-dependent agent), and SNP (10−7 M, an endothelium-independent agent) before and after the administration of the air bolus. The infusion of air resulted in loss of function of the endothelium, as indicated by the absence of dilation to ACh, whereas dilation to SNP remained intact.

Responses to increasing concentration of pinacidil (an opener of ATP-dependent K+-channel; 10−8–10−4 M) were obtained before and after incubation with glibenclamide (10−6M; 30 min). Arteriolar responses were obtained to increasing concentrations of 4-AP (10−6–3×10−4 M).

In a second series of experiments responses of arterioles to cumulative doses of noradrenaline (NA, 10−9–10−5 M) and 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT, 10−9–10−5 M) were obtained. Then the vessel was incubated with fluoxetine (10−6, 2×10−6 or 10−5 M) for 5 min and vasoactive responses were reassessed. After removal of the endothelium a Ca2+ free PSS was used to superfuse the vessels until maximal dilation developed. Then changes in diameter in response to increasing concentrations of Ca2+ (10−4–3×10−2 M) were assessed before and after preincubation with fluoxetine (2×10−6 and 10−5 M; for 5 min). The osmolality of the bathing fluid was adjusted to 300 mosm at every concentration of CaCl2 administered. All drugs were added to the vessel chamber and final concentrations are reported in the text. After responses to each drug subsided, the system was flushed with PS solution.

Materials

Fluoxetine and pinacidil were obtained from Research Biochemicals International (RBI) and Sigma Co. (U.S.A.). All other salts and chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (U.S.A.) and were prepared on the day of the experiment. Pinacidil was dissolved immediately before use in a small volume of 0.01N HCl and was diluted in buffer. 10−2 M stock of glibenclamide was prepared by dissolving the substance in 30% w v−1 (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin (Cyclolab R&D Ltd, Hungary), adding a small volume of 40% v v−1 ethanol and dissolving in buffer. Fluoxetine was dissolved in PS solution.

Data analysis

Dilations were expressed as a percentage of the maximal dilation of arterioles defined as the passive diameter at 80 mmHg perfusion pressure in Ca2+ free media containing 10−3 M EGTA and 10−4 M SNP. Constrictions were expressed as a percentage of the baseline diameter. From the logarithmic regressions of the cumulative dose-response curves of vasoactive agents the 50% effective concentrations (EC50) were calculated. Where the drug interaction was apparently competitive, the negative logarithm (pA2) of the equilibrium dissociation constant (Ke) was calculated for the antagonist (Arunlakshana & Schild, 1959; Kosterlitz & Watt, 1968). The Ke was calculated from the equation Ke=a/(DR-1) where ‘a' is the molar concentration of antagonist and ‘DR', the dose ratio, is the measure of the rightward shift of the agonist dose-response curve. In the graphical plots the arithmetic mean±s.e.mean values were used, whereas for the other parameters (EC50, pA2) means and s.d. values were calculated. Statistical analyses were performed by analysis of variance followed by Student's t-test. P values less than 0.05 (P<0.05) were considered statistically significant.

Results

Arterioles isolated from rat gracilis muscle developed spontaneous, myogenic tone in response to increasing the perfusion pressure to 80 mmHg without the use of any vasoactive agents. The active inner diameter of arterioles was 98±4 μm. The passive diameter of arterioles obtained in the same conditions but in the absence of Ca2+ (see Methods) was 155±5 μm.

Arteriolar responses to fluoxetine: role of endothelium

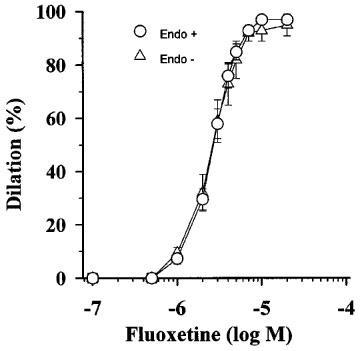

Fluoxetine (10−6 to 10−5 M) elicited substantial dilations in arterioles with an EC50 of 2.5±0.5×10−6 M in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1). We have also found that removal of endothelium had no significant effect on dilator responses of arterioles to fluoxetine (EC50=2.6±0.4×10−6 M; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of cumulative doses of fluoxetine on normalized diameter of arterioles isolated from rat gracilis muscle with intact endothelium (Endo+; n=10) and after the endothelium removal (Endo−; n=7). Data are mean±s.e.mean.

Role of potassium channels

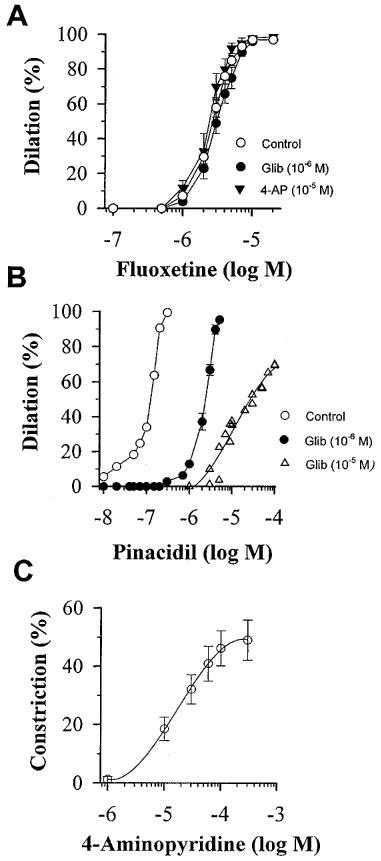

Next, we tested the possible role of ATP- and 4-aminopyridine-sensitive K+-channels in the vasodilator action of fluoxetine. First we demonstrated that these K+-channels are present in the gracilis arterioles. The ATP-sensitive K+ channel opener pinacidil dilated the arterioles (Figure 2B) with an EC50 of 1.1±0.3×10−7 M. Glibenclamide in a concentration of 10−6 M caused an approximately 20 fold significant (P<0.01), parallel rightward shift of pinacidil dose-response curve without affecting the maximum response. The further significant (P<0.01) rightward shift by 10−5 M glibenclamide was non-parallel. From the parallel shift, assuming a competitive interaction, a pA2 of 7.3±0.2 was calculated. 4-aminopyridine (10−5–10−3 M) constricted the gracilis arterioles in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2C). After preincubation and in the presence of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel inhibitor glibenclamide (10−6 M) fluoxetine-induced dilations of arterioles did not change significantly (EC50=2.9±0.5×10−6 M; Figure 2A). Similarly, preincubation of arterioles with 4-aminopyridine (10−5 M) did not affect the fluoxetine dose-response curve (EC50=2.3±0.5×10−6 M; Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Effect of cumulative doses of fluoxetine on normalized diameter of arterioles isolated from rat gracilis muscle in control conditions (Control, n=10), in the presence of 10−6 M glibenclamide (Glib, n=5), or 10−5 M 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, n=5). (B) Effect of cumulative doses of pinacidil in the absence (Control, n=4) or in the presence of 10−6 M (n=4) or 10−5 M (n=2) glibenclamide (Glib). (C) Effect of cumulative doses of 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) on normalized diameter of gracilis arterioles (n=5). Data are means±s.e.mean.

Arteriolar responses to noradrenaline and 5-hydroxytryptamine

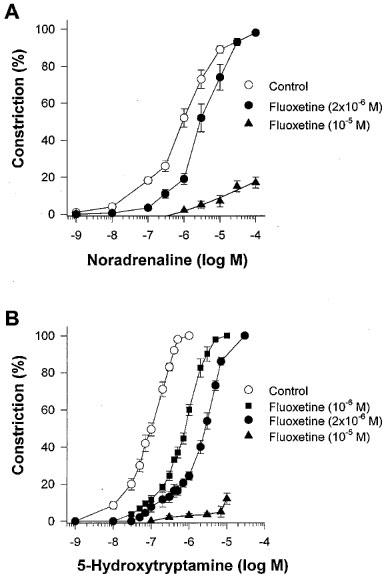

Next, we aimed to test the hypothesis that fluoxetine may interact with noradrenaline (NA) or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptors and/or the signal cascades. Therefore we tested arteriolar responses to NA and 5-HT. Noradrenaline constricted arterioles in a concentration-dependent manner with an EC50 of 1.2±0.4×10−6 M (Figure 3A). Fluoxetine (2×10−6 M) caused an approximately 4 fold significant (P<0.05), parallel rightward shift of NA dose-response curve without affecting the maximum response. From the parallel shift, a pA2 of 6.1±0.1 was calculated.

Figure 3.

(A) Changes in normalized diameter of rat gracilis arterioles in response to cumulative doses of noradrenaline (NA) in the absence (Control, n=6) or presence of 2×10−6 M (n=6) or 10−5 M (n=4) fluoxetine. (B) Changes in diameter of rat gracilis arterioles in response to cumulative doses of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) in the absence (Control, n=6) or presence of 10−6 M (n=6), 2×10−6 M (n=6) or 10−5 M (n=4) fluoxetine. Data are means±s.e.mean.

5-Hydroxytryptamine constricted the arterioles in a concentration-dependent manner with an EC50 of 1.1±0.3×10−7 M (Figure 3B). Fluoxetine (10−6 M and 2×10−6 M) caused an approximately 10 and 20 fold, parallel rightward shift of 5-HT dose-response curve respectively, without affecting the maximum response. From the parallel shifts, a pA2 of 6.9±0.1 was calculated. The calculated slope of Schild regression was −1.1, indicating competitive antagonism. Fluoxetine in a higher concentration (10−5 M) markedly reduced responses to 5-HT (10−8–10−5 M; n=4) and NA (10−8–10−4 M; n=4) (Figure 3A and 3B, respectively).

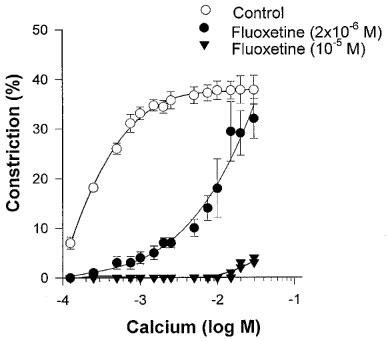

Arteriolar responses to Ca2+

In order to elucidate the possible role of altered Ca2+ sensitivity in fluoxetine-induced dilation we tested the arteriolar responses to increasing concentrations of calcium. In the absence of Ca2+ endothelium-denuded arterioles dilated maximally. Administration of Ca2+ (10−4–3×10−2 M) in a dose-dependent manner elicited constrictions, restoring the myogenic tone of arterioles (developed in response to 80 mmHg perfusion pressure) (Figure 4). The dose-response curve to the increasing concentration of Ca2+ was characterized by a steep part indicating substantial constriction (10−4–7.5×10−4 M) and a plateau phase (10−3–3×10−2 M), where the arteriolar tone was maintained. The presence of 2×10−6 M and 10−5 M fluoxetine in the bath solution markedly (P<0.01) reduced Ca2+-elicited constrictions compared to controls (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Changes in normalized diameter to increasing concentrations of calcium (CaCl2) in the absence (Control, n=8) and in the presence of 2×10−6 M (n=5), or 10−5 M (n=4) fluoxetine. Data are means ±s.e.mean.

Discussion

The main findings of our study are that the serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine dilates isolated rat skeletal muscle arterioles; this dilation is not mediated by 4-AP- or ATP-sensitive K+ channels or endothelium-derived dilator factors; fluoxetine reduced arteriolar constrictions to NA and 5-HT in a competitive manner, and had a substantial inhibitory effect on Ca2+-elicited constrictions.

Although fluoxetine is regarded a specific inhibitor of serotonin reuptake in the neural tissue there are studies indicating that fluoxetine may have cardiovascular effects as well. There is an increasing number of case reports on bradycardia, dysrhythmia (Buff et al., 1991; Friedman, 1991; Anderson & Compton, 1997) and hypotensive events (Ellison et al., 1990; McAnally et al., 1992; Cherin et al., 1997; Livshits & Danenberg, 1997; Rich et al., 1998) associated with fluoxetine treatment. Interestingly in an early study the blood pressure lowering effect of fluoxetine has been described in DOCA-hypertensive rats (Fuller et al., 1979). The authors hypothesized that a central action of fluoxetine on vasomotor centre underlies this effect, but the possible direct cardiac and peripheral vascular effects of fluoxetine were not elucidated.

In the present study we hypothesized that fluoxetine may affect the tone of resistance arterioles thereby promoting vasodilation and hypotension. Thus we aimed to characterize the direct effect of fluoxetine on the vasomotor tone of isolated rat gracilis muscle arterioles.

Fluoxetine dilates skeletal muscle arterioles

We have demonstrated that fluoxetine has a concentration-dependent vasodilator action in skeletal muscle arterioles with an EC50 of 2.5±0.5×10−6 M (Figure 1). These microvessels are representative of resistance vessels determining peripheral vascular resistance. The concentration of fluoxetine which has a substantial dilator effect falls into the upper range of therapeutic plasma concentrations (0.15–1.5×10−6 M) (Orsulak et al., 1988; Kelly et al., 1989; Pato et al., 1991). Previous studies reported similar concentrations of norfluoxetine, the active metabolite of fluoxetine also present in the plasma of fluoxetine-treated patients (Orsulak et al., 1988; Kelly et al., 1989; Pato et al., 1991). Furthermore, under certain conditions (e.g. decreased metabolism in elderly, acute overdose etc) the plasma concentration of fluoxetine and norfluoxetine can reach even higher levels (Pato et al., 1991; Borys et al., 1992; Hale, 1993). In addition, it is possible that fluoxetine can be accumulated in various tissues. During chronic fluoxetine treatment a concentration of fluoxetine 20 times higher than the plasma has been detected in human brain (Karson et al., 1993; Komoroski et al., 1994). Collectively, these findings suggest that under certain conditions the concentration of fluoxetine could reach levels which may affect peripheral vascular tone.

Possible mechanisms of action: role of endothelium

Removal of the endothelium did not affect fluoxetine induced dilations (Figure 1). Therefore we conclude that fluoxetine exerts its effect directly on the arteriolar smooth muscle cells without endothelial mediation.

Role of K+ channels

As earlier studies suggested that fluoxetine may affect various K+ channels in cells, we hypothesized that opening of arteriolar K+ channels may play a role in the vasodilator action of fluoxetine. First we demonstrated the presence of the ATP-sensitive K+ channels and the 4-AP-sensitive K+ channels on the gracilis arteriole (Figure 2). Pinacidil, a known ATP-sensitive K+ channel opener dilated the arterioles and this dilation could be competitively antagonized with glibenclamide, a specific inhibitor of this channel type. The non-selective inhibitor of various K+ channels, 4-AP elicited significant constriction of the gracilis arterioles indicating that these channels are functional in the regulation of basal arteriolar tone. However, neither the inhibition of the ATP-sensitive K+ channels, nor the 4-AP sensitive K+ channels significantly affected the vasodilator action of fluoxetine (Figure 2).

Role of NA/5-HT receptor inhibition

It is well documented that tricyclic antidepressant drugs act on 5-HT and NA receptors both in the central nervous system and in the cardiovascular system (Baldessarini, 1997). Fluoxetine is also known to interfere with 5-HT receptors and/or signal transduction pathways in central nervous system (Fan, 1994; Ni & Miledi, 1997). However, less is known about the possible interaction between fluoxetine and 5-HT and NA receptors in vascular tissue. Similarly to previous studies (Koller et al. 1995b), NA and 5-HT elicited substantial constrictions of gracilis muscle arterioles. In the present study we found that fluoxetine caused a parallel rightward shift both in the 5-HT and NA dose-response curves in skeletal muscle arterioles. On the basis of these data one can assume, that fluoxetine antagonizes 5-HT and NA receptors in resistance arterioles.

Role of Ca2+-sensitivity

It is known that an increase in intracellular Ca2+ in the arteriolar smooth muscle follows the stimulation of various NA and 5-HT receptors and is also necessary for maintaining myogenic arteriolar tone. It is well documentated (Hill & Meininger, 1994; Koller et al., 1995a; Sun et al., 1996; Koller & Huang, 1997) that arteriolar myogenic constriction which develops in response to increases in intraluminal pressure depends on the activity of Ca2+ channels in the vascular smooth muscle cells. In the absence of Ca2+, arterioles dilated maximally, subsequent administration of increasing doses of Ca2+ elicited substantial constriction. Thus, at 80 mmHg perfusion pressure we studied the magnitude of Ca2+-induced myogenic tone in the presence of fluoxetine (2×10−6 M), which markedly reduced calcium-induced vasoconstriction (a ∼50 fold rightward shift of Ca2+ dose-response curve), whereas a higher concentration of fluoxetine (10−5 mol−1 L) practically abolished Ca2+-induced responses. Comparison of data indicates that fluoxetine reduces arteriolar Ca2+ sensitivity more effectively than the constrictor responses to NA or 5-HT. Therefore it is likely that fluoxetine elicits dilation by inhibiting Ca2+ entry to vascular smooth muscle cell. Previous studies support this hypothesis, demonstrating that fluoxetine antagonizes neuronal Ca2+ channels (Stauderman et al., 1992; Lavoie et al., 1997). Furthermore, we have recently found that fluoxetine caused a concentration-dependent decrease in contractile force and depression of the amplitude, overshoot and maximum rate of rise of depolarization of action potential in right ventricular papillary muscles of the rat (Pacher et al., 1998).

Collectively, these findings support the hypothesis that fluoxetine by inhibiting Ca2+ channel activity and/or altering Ca2+ sensitivity of smooth muscle cell, elicits an endothelium-independent arteriolar dilation. The fluoxetine induced reduction in arteriolar tone may underlie the hypotensive events occasionally observed during fluoxetine administration. It is also interesting to note that several vasorelaxant Ca2+ channel antagonists, especially dihydropyridine derivatives, were found to exert certain antidepressant effects (Nowak et al., 1993). Future studies should determine the possible involvement of inhibition of vascular and/or neural Ca2+ channels in the antidepressant action of fluoxetine.

In conclusion we found that fluoxetine elicits substantial dilation of isolated skeletal muscle arterioles. This response is not mediated by 4-AP- or ATP-sensitive K+ channels or endothelium-derived dilator factors. Our results suggest that fluoxetine may antagonize adrenergic and serotinergic receptors and/or block either entry of Ca2+ or may interfere with the Ca2+-signal transduction in the arteriolar smooth muscle cells, favouring reduction of vascular resistance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Andras Ronai and Peter Rajna for their advice of great value. This work was supported by Grants from the Hungarian National Science Research Foundation OTKA T-023863, OTKA T-019206, the Health Science Council ETT 524/97 and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute U.S.A. HL-46813.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- 4-AP

4-aminopyridine

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- DOCA

desoxycorticosterone acetate

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- Endo+

intact endothelium

- Endo−

endothelium removal

- Glib

glibenclamide

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- PS

physiological salt

- NA

noradrenaline

- SNP

sodium nitroprusside

- SSRI

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

References

- ANDERSON J., COMPTON S.A. Fluoxetine induced bradycardia in presenile dementia. Ulster Med. J. 1997;66:144–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARUNLAKSHANA O., SCHILD H.O. Some quantitative uses of drug antagonists. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1959;14:48–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1959.tb00928.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BALDESSARINI R.J.Drugs and the treatment of psychiatric disorders The pharmacological basis of therapeutics 1997New York: McGraw-Hill; 431–460.9th edition. eds. Hardman, J.G; Limbird, L.E.; Molinoff, P.B.; Ruddon, R.W. & Gilman, A.G. pp [Google Scholar]

- BOEHNERT M.T., LOVEJOY F.H., JR Value of the QRS duration versus the serun drug level in predicting seizures and ventricular arrhythmias after an acute overdose of tricyclic antidepressants. N. Engl. J. Med. 1985;313:474–479. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198508223130804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BORYS D.J., SETZER S.C., LING L.J., REISDORF J.J., DAY L.C., KRENZELOK E.P. Acute fluoxetine overdose: a report of 234 cases. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1992;10:115–120. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(92)90041-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUFF D.D., BRENNER R., KIRTANE S.S., GILBOA R. Dysrhythmia associated with fluoxetine treatment in elderly patients with cardiac disease. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1991;52:174–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURCKHARDT D., RAEDER E., MULLER V., IMHOF P., NEUBAUER H. Cardiovascular effects of tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants. J.A.M.A. 1978;239:213–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASTLE N.A., HAYLETT D.G., JENKINSON D.H. Toxins in the characterization of potassium channels. T.I.N.S. 1989;12:59–65. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHERIN P., COLVEZ A., DEVILLE, DE PERIERE G., SERENI D. Risk of syncope in the elderly and consumption of drugs: a case-control study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1997;50:313–320. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00385-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLUNGA G.J., AWAD J.N., MILEDI R. Blockage of muscle and neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by fluoxetine (Prozac) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:2041–2044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLISON J.M., MILOFSKY J.E., ELY E. Fluoxetine- induced bradycardia and syncope in two patients. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1990;51:385–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAN P. Inhibition of a 5-HT3 receptor-mediated current by the selective serotonin uptake inhibitor, fluoxetine. Neurosci. Lett. 1994;173:210–212. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FARRUGIA G. Modulation of ionic currents in isolated canine and human jejunal circular smooth muscle cells by fluoxetine. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1438–1445. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRIEDMAN E.H. Fluoxetine-induced bradycardia. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1991;52:174–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FULLER R.W., HOLLAND D.R., YEN T.T., BEMIS K.G., STAMM N.B. Antihypertensive effects of fluoxetine and L-5-hydroxytryptophan in rats. Life Sci. 1979;25:1237–1242. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(79)90466-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIARDINA E.G., BIGGER J.T., JR, GLASSMAN A.H., PEREL J.M., KANTOR S.J. The electrocardiographic and antiarrhytmic effects of imipramine hydroclorid at therapeutic plasma concentrations. Circulation. 1979;60:1045–1052. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.60.5.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLASSMAN A.H. Cardiovascular effects of tricyclic antidepressants. Annu. Rev. Med. 1984;35:503–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.35.020184.002443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLASSMAN A.H., BIGGER J.T., JR, GIARDINA E.V., KANTOR S.J., PEREL J.M., DAVIES M. Clinical characteristics of imipramine-induced orthostatic hypotension. Lancet. 1979;1:468–472. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90824-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALE A.S. New antidepressants: use in high-risk patients. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1993;54:61–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYES J.R., BORN J.F., ROSENBAUM A.H. Incidence of orthostatic hypotension in patients with primary affective disorders treated with tricyclic antidepressants. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1977;52:509–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILL M.A., MEININGER G.A. Calcium entry and myogenic phenomena in skeletal muscle arterioles. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;267:H1085–H1092. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.3.H1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARSON C.N., NEWTON J.E., LIVINGSTON R., JOLLY J.B., COOPER T.B., SPRIGG J., KOMOROSKI R.A. Human brain fluoxetine concentrations. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1993;5:322–329. doi: 10.1176/jnp.5.3.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KELLY M.W., PERRY P.J., HOLSTAD S.G., GARVEY M.J. Serum fluoxetine and norfluoxetine concentrations and antidepressant response. The Drug Monit. 1989;11:165–170. doi: 10.1097/00007691-198903000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOLLER A., HUANG A. Endothelin and prostaglandin H2 enhance arteriolar myogenic tone in hypertension. Hypertension. 1997;30:1210–1215. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.5.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOLLER A., HUANG A., SUN D., KALEY G. Exercise training augments flow-dependent dilation in rat skeletal muscle arterioles. Role of endothelial nitric oxide and prostaglandins. Circ. Res. 1995a;76:544–550. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOLLER A., RODENBURG J.M., KALEY G. Effects of Hoe-140 and ramiprilat on arteriolar tone and dilation to bradykinin in skeletal muscle of rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1995b;268:H1628–H1633. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.4.H1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOMOROSKI R.A., NEWTON J.E., CARDWELL D., SPRIGG J., PEARCE J., KARSON C.N. In vivo 19F spin relaxation and localized spectroscopy of fluoxetine in human brain. Magn. Reson. Med. 1994;31:204–211. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910310214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOSTERLITZ H.W., WATT A.J. Kinetic parameters of narcotic agonists and antagonists, with particular reference to N-allylnoroxymorphone (naloxone) Br. J. Pharmacol. 1968;33:266–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1968.tb00988.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAVOIE P.A., BEAUCHAMP G., ELIE R. Atypical antidepressants inhibit depolarization-induced calcium uptake in rat hippocampus synaptosomes. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1997;75:983–987. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-75-8-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIVSHITS A.T.L., DANENBERG H.D. Tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension and profound weakness due to concomitant use of fluoxetine and nifedipine. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1997;30:274–275. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCANALLY L.E., THRELKELD K.R., DREYLING C.A. Case report of a syncopal episode associated with fluoxetine. Ann. Pharmacother. 1992;26:1090–1091. doi: 10.1177/106002809202600909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NI Y.G., MILEDI R. Blockage of 5HT2C serotonin receptors by fluoxetine (Prozac) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:2036–2040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOWAK G., PAUL I.A., POPIK P., YOUNG A., SKOLNICK P. Ca2+ antagonists effect an antidepressant-like adaptation of the NMDA receptor complex. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;247:101–102. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(93)90144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORSULAK P.J., KENNEY J.T., DEBUS J.R., CROWLEY G., WITTMAN P.D. Determination of the antidepressant fluoxetine and its metabolite norfluoxetine in serum by reversed-phase HPLC, with ultraviolet detection. Clin. Chem. 1988;34:1875–1878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PACHER P., KECSKEMETI V., UNGVARI Z., KOROM S., PANKUCSI C. Cardiodepressant effects of fluoxetine in isolated heart preparations. Naunyn-Schmideberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1998;358 suppl 2:R641. [Google Scholar]

- PANCRAZIO J.J., KAMATCHI G.L., ROSCOE A.K., LYNCH C. Inhibition of neuronal Na+ channels by antidepressant drugs. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;284:208–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATO M.T., MURPHY D.L., DEVANE C.L. Sustained plasma concentrations of fluoxetine/or norfluoxetine four or eight weeks after fluoxetine discontinuation. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1991;11:224–225. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199106000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAE J.L., RICH A., ZAMUDIO A.C., CANDIA O.A. Effect of Prozac on whole cell ionic currents in lens and corneal epithelia. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;269:C250–C256. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.1.C250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RICH J.M., NJO L., ROBERTS K.W., SMITH K.P. Unusual hypotension and bradycardia in a patient receiving fenfluramine, phentermine and fluoxetine. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:529–531. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199802000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STAUDERMAN K.A., GANDHI V.C., JONES D.J. Fluoxetine-induced inhibition of synaptosomal (3H)5-HT release: possible Ca2+-channel inhibition. Life Sci. 1992;50:2125–2138. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90579-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUN D., KALEY G., KOLLER A. Characteristics and origin of myogenic response in isolated gracilis muscle arterioles. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;266:H1177–H1183. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.3.H1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TYTGAT J., MAERTENS C., DAENENS P. Effect of fluoxetine on a neuronal, voltage-dependent potassium channel (Kv1.1) Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:1417–1424. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VELASCO A., ALAMO C., HERVAS J., CARVAJAL A. Effects of fluoxetine hydrochloride and fluvoxamine maleate on different preparations of isolated guinea-pig and rat organ tissues. Gen. Pharmacol. 1997;28:509–512. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VOHRA J., BURROWS G., HUNT D., SLOMAN G. The effects of toxic and therapeutic doses of tricyclic antidepressant drugs on intracardiac conduction. Eur. J. Cardiol. 1975;3:219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]