Abstract

Although cholecystokinin octapeptide sulphate (CCK-8) activates the opioid system of isolated guinea-pig ileum (GPI) whether it activates the μ- or κ-system, or both, remains unclear. Neither is it known whether CCK-8 influences the withdrawal responses in GPI preparations briefly exposed to opioid agonists. This study was designed to clarify whether CCK-8 activates μ- or κ-opioid systems or both; and to investigate its effect on the withdrawal contractures in GPI exposed to μ- or κ-agonists and on the development of tolerance to the withdrawal response.

In GPI exposed to CCK-8, the selective κ-antagonist nor-binaltorphimine elicited contractile responses that were concentration-related to CCK-8 whereas the selective μ-antagonist cyprodime did not.

In GPI preparations briefly exposed to the selective μ-agonist, dermorphin, or the selective κ-agonist, U-50, 488H, and then challenged with naloxone, CCK-8 strongly enhanced the withdrawal contractures.

During repeated opioid agonist/CCK-8/opioid antagonist tests tolerance to opioid-induced withdrawal responses did not develop.

These results show that CCK-8 preferentially activates the GPI κ-opioid system and antagonizes the mechanism(s) that control the expression of acute dependence in the GPI.

Keywords: Cholecystokinin; opioids; guinea-pig ileum; withdrawal contracture; dermorphin; U-50, 488H

Introduction

Substantial data on antinociception and the development of tolerance to the antinociceptive effect have shown the complex interaction between cholecystokinin (CCK) and opioid systems (for a review see Cesselin, 1995). Earlier evidence that daily administration of CCK antagonists left the withdrawal syndrome in morphine-dependent animals unaffected (Dourish et al., 1988; Panerai et al., 1987; Xu et al., 1992) and that CCK agonists did not precipitate a withdrawal syndrome in dependent animals (Maldonado et al., 1994; Pournaghash & Riley, 1991) suggested that the development or expression of physical dependence did not involve CCK systems. However, later works showed that CCK agonists reduced or prevented the withdrawal signs precipitated by naloxone in morphine-dependent mice (Zarrindast et al., 1995; Rezayat et al., 1997). On the other hand, a CCKB receptor antagonist potentiated the inhibition of morphine withdrawal of an inhibitor of enkephalin catabolism (Maldonado et al., 1995).

Several studies focusing on the biochemical processes involved in physical dependence to opiates have used isolated guinea-pig ileum (GPI), a tissue that contains both μ- and κ-opioid receptors (Hutchinson et al., 1975; Dissanayake et al., 1990). The opioid antagonist-precipitated withdrawal contractions elicited in GPI briefly exposed to opioid agonists and withdrawal signs in the intact animal have similar pharmacological characteristics (Lujan & Rodriguez, 1981; Valeri et al., 1990a; Brent et al., 1993; Morrone et al., 1993). Evidence that GPI tissues briefly exposed to CCK octapeptide sulphate (CCK-8) contract on the addition of naloxone shows that this peptide indirectly activates the GPI opioid system(s) (Garzon et al., 1987; Valeri et al., 1990b). Like the naloxone-induced withdrawal response in morphine-dependent tissues, the naloxone-induced response in CCK-8-dependent tissues is mediated by neuronal ACh release because atropine, clonidine and tetrodotoxin inhibit both responses (Garzon et al., 1987; Valeri et al., 1990a,1990b). None of these studies investigated the influence of CCK- 8 on opioid withdrawal response.

Because withdrawal responses in GPI preparations briefly exposed to opioid agonists show strong self blockade (Cruz et al., 1991), μ (Chahl, 1990) and κ withdrawal contractions (Brent et al., 1993) can be obtained only once in an isolated preparation. In an earlier study we showed that stimulation of the μ-opioid system with selective μ-agonists indirectly activates the κ-system, which in turn inhibits the μ-system withdrawal response, and conversely, stimulation of κ-opioid system with selective κ-agonists indirectly activates the μ-system, which in turn inhibits the κ-system withdrawal response (Valeri et al., 1996). Hence, we attributed the declining responsiveness of GPI preparations to repeated μ- or κ-agonist/antagonist tests to a mutual antagonistic interaction between the μ- and κ-opioid systems. Interestingly, when CCK-8 was added before the antagonists tolerance to repeated agonist/antagonist tests did not develop (Valeri et al., 1990b). Hence, CCK-8 might prevent tolerance from developing, possibly by interfering with the μ/κ interaction.

Our aim in this study was to find out whether CCK-8 activates μ- or κ-opioid systems or both; how it affects the withdrawal contractures elicited in isolated GPI exposed to μ- or κ-agonists; and what effect it has on the μ/κ interaction and on the development of tolerance.

Methods

The experimental procedure was essentially that used by Valeri et al. (1990a). Adult male guinea-pig (300–400 g) purchased from Morini (Italy) were killed by a blow to the head and bled. Three to six segments, 2–3 cm long, of the ileum were excised from the same animal, discarding the 10 cm nearest the caecum. The segments were cleaned with Tyrode's solution and set up under 1 g tension in a 10 ml organ bath containing Tyrode's solution, maintained at 37°C and gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Changes in tension were recorded by an isotonic force transducer connected to a pen recorder (Ugo Basile, 7066 and 7050, Italy) and calibrated before each experiment. The preparations were allowed to equilibrate for 30–40 min and then stimulated two or three times with ACh (10−7–10−6 M) to ascertain their suitability. The contractile responses were expressed as per cent of the maximal ACh response.

To eliminate possible spontaneous responses to opioid antagonists in naïve tissues (Valeri et al., 1996), before the experiments, tissue preparations were exposed for 5 min to naloxone (5.4×10−7 M), naloxone was washed out and 30 min later the experiments began.

Tissue preparations were generally used for several consecutive tests and were washed out once immediately after each test; thereafter, they were allowed to rest for 30 min and were washed three times between tests.

Contractures to naloxone and selective μ- and κ-opioid antagonists after exposure to CCK-8: Effects of CCK antagonists on the responses to CCK-8 and opioid antagonists

Tissue preparations were first tested with naloxone and then repeatedly exposed to CCK-8 (0.08–10×10−9 M) (previous studies had shown that CCK-8 activates the GPI opioid system in this range of concentrations (Garzon et al., 1987; Valeri et al., 1990b). After each exposure, naloxone (5.4×10−7 M), the selective μ-antagonist (Schmidhammer et al., 1989) cyprodime (1.4×10−6 M), or the selective κ-antagonist (Portoghese et al., 1987) nor-binaltorphimine (3.4×10−8 M), were added at the declining tonic response to CCK-8. In preliminary experiments, these antagonist concentrations were found to yield maximal, reproducible responses. In addition, at these concentrations the antagonists are selective because we had previously found that cyprodime (1.4×10−6 M) evoked a withdrawal contracture only in tissue preparations exposed to the μ-agonist, dermorphin, and, conversely, nor-binaltorphimine (3.4×10−8 M) evoked a withdrawal contracture only in preparations exposed to the κ-agonist, U-50,488H (Valeri et al., 1996). To test whether μ-opioid receptor blockade influenced the contractile response to the κ-opioid antagonist, and vice versa, in some preparations, cyprodime (4.5 and 14×10−7 M) or nor-binaltorphimine (1.1 and 3.4×10−8 M) were added 1 or 5 min before CCK-8 (2×10−9 M). These antagonist concentrations were those previously found to block the inhibitory effect of indirect μ-activation on κ-withdrawal contracture and vice versa (Valeri et al., 1996).

To investigate whether the activation of opioid system was mediated by CCKA or CCKB receptors, we tested the effects of the selective CCKA antagonist (Boden et al., 1993; Singh et al., 1995) PD-140,548 (1.2–80×10−8 M), and the selective CCKB antagonist (Lotti & Chang, 1989) L-365,260 (1.2×10−9–10−6 M), added 5 min before CCK-8 (4×10−10 M). A rather low CCK-8 concentration was chosen for these tests because preliminary tests with the CCKA antagonist had suggested that the CCKA receptor-mediated (Dal Forno et al., 1992; Corsi et al., 1994) tonic response to CCK-8 could be totally inhibited only at high CCKA antagonist/CCK-8 concentration ratios, and the response to the opioid antagonist was even more resistant. The data from functional studies suggested that antagonist/CCK-8 concentration ratios higher than those expected from binding data might be needed to achieve a full inhibition of both CCKA (Singh et al., 1995) and CCKB (Lucaites et al., 1991) receptor-mediated responses. Therefore, we tested the CCK antagonists also at concentrations yielding CCK antagonist/CCK-8 ratios of concentrations higher than those derivable from the binding data (Singh et al., 1995; Suman-Chauhan et al., 1996). In the tests with PD-140,548, the antagonist concentration was raised until achieving a full inhibition of the tonic response to CCK-8. In the tests with L-365,260, the antagonist concentration was raised until an inhibition of the tonic response to CCK-8 was observed, which indicated that the L-365,260 also occupied CCKA receptors.

Effects of μ- and κ-opioid agonists on the tonic response to CCK-8 and the response to opioid antagonists

GPI tissue preparations were tested twice with CCK-8/naloxone (CCK-8: 2×10−9 M; naloxone: 5.4×10−7 M). In subsequent tests, tissue preparations were exposed to the selective μ-agonist, dermorphin (1.2–24×10−9 M) or the selective κ-agonist, U-50,488H (5.4–107.4×10−9 M) for 2 min before CCK-8 (2×10−9 M) was added to the bath. Opioid antagonists were added at the declining tonic response (i.e., about 2 min after CCK-8); for the highest opioid agonist concentrations that completely inhibited the contractile response to CCK-8, the antagonists were added 2 min after the peptide. In some experiments, the antagonists were added 8 min after CCK-8, i.e., when the response to CCK-8 (without opioid agonists) had faded. Dermorphin-exposed tissue preparations were challenged with naloxone (5.4×10−7 M) or cyprodime (1.4×10−6 M); U-50,488H-exposed tissues with naloxone (5.4×10−7 M) or nor-binaltorphimine (3.4×10−8 M). For each dermorphin concentration, the dermorphin/CCK-8/opioid antagonist test was repeated three times because preliminary findings had suggested that the response to cyprodime or naloxone increased in intensity up to the third test and remained constant thereafter; after these three tests, a CCK-8/opioid antagonist test was performed before testing – 45 min after the last CCK-8/opioid antagonist test – a higher dermorphin concentration. For each U-50,488H concentration, the U-50,488H/CCK-8/opioid antagonist test was repeated twice; thereafter a CCK-8/opioid antagonist test was performed before testing a higher U-50,488H concentration. In each tissue preparation, 1-2 dermorphin concentrations or 2-3 U-50,488H concentrations were tested.

To study the change in opioid effects in repeated tests each test was repeated three to five times in the same tissue preparation. To study the effect of κ-receptor blockade on the μ-withdrawal response in tissues exposed to dermorphin and CCK-8, nor-binaltorphimine (3.4×10−8 M) was added 1 min before cyprodime (i.e., 1 min after CCK-8). The effect of μ-receptor blockade on the κ-withdrawal response in tissues exposed to U-50,488H and CCK-8 was evaluated by adding cyprodime (1.4×10−6 M) 1 min before nor-binaltorphimine.

Effect of CCK-8 on the withdrawal responses to naloxone in GPI tissues exposed to μ- or κ-agonists

Because opioid antagonists also elicit a withdrawal contracture in GPI tissue preparations exposed to opioid agonists alone (Chahl, 1986; Valeri et al., 1990a; Morrone et al., 1993), we compared tissue responses to opioid antagonists with and without CCK-8, using opioid agonist concentrations yielding submaximal withdrawal responses.

After a first test with CCK-8/naloxone (CCK-8: 0.4–10×10−9 M; naloxone: 5.4×10−7 M), tissue preparations, were exposed for 5 min to dermorphin (1.2–6×10−9 M) or U-50,488H (5.4×10−9 M) and then challenged with naloxone (5.4×10−7 M). This agonist/antagonist test was repeated twice. In the subsequent tests, CCK-8 (0.4–10×10−9 M) was added 2 min after the opioid agonist, and naloxone 2 min after CCK-8.

To study the effect of CCK antagonists on CCK-8 enhancement of the μ withdrawal response, tissue preparations were tested as described above. After the test with dermorphin/CCK-8/naloxone (dermorphin: 1.2×10−9 M; CCK-8: 4×10−10 M), the preparations were washed out and exposed either to the CCKA antagonist, PD-140,548 (1 and 8×10−7 M), or to the CCKB antagonist, L-365,260 (2.5 and 10×10−7 M); dermorphin (1.2×10−9 M) was added 3 min after the CCK antagonists, CCK-8 (4×10−10 M) 2 min after the opioid agonist, and naloxone 2 min after CCK-8.

Statistical analysis

The contractile responses were expressed as a percentage of the maximum response to ACh (10−6–10−7 M). Statistical significance of the differences of responses was evaluated by one-way ANOVA, followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test, or by one-way ANOVA for repeated measures, followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test, as appropriate.

Drugs

Cholecystokinin octapeptide sulphate was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.), naloxone hydrochloride from SIFAC (Milan, Italy), U-50,488H (trans±3, 4 - dichloro - N - methyl - N-[2-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-cyclohexyl]-benzene-acetamide methane sulphonate) from Upjohn Co. (Kalamazoo, MI, U.S.A.), nor-binaltorphimine dihydrochloride, cyprodime and PD 140,548 N-methyl-D-glucamine ([S - (R*,S* - β - [[3 - (1H - Indol - 3 - yl)-2-methyl-1-oxo-2-[[tricyclo[3.3.1.13,7]dec-2-yloxy)carbonyl]amino]propyl]amino]-benzenebutanoic acid N-methyl-D-glucamine) from Research Biochemicals International (Natick, MA, U.S.A.). L-365,260 ((3R)-3[N'-(3-methylphenyl) ureido]-1, dihydro-1-methyl-5-phenyl-2H-1,4-benzo-diazepin-2-one) was a generous gift from ML Laboratories PLC (Liverpool, England). Dermorphin was a generous gift from Professor V. Erspamer.

Results

Contractile responses to naloxone, cyprodime and nor-binaltorphimine in GPI tissues exposed to CCK-8

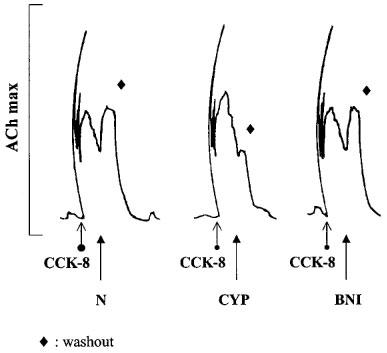

In isolated GPI preparations CCK-8 (0.08–10×10−9 M) evoked a contraction normally consisting of two components: a phasic response, characterised by a sharp spike lasting a few seconds, and a tonic response, which declined more slowly. In the first CCK-8/opioid antagonist tests and at all CCK-8 concentrations the selective κ-antagonist, norbinaltorphimine (3.4×10−8 M) and the non selective antagonist, naloxone (5.4×10−7 M) (added to the bath during the declining tonic response to CCK-8) elicited a contracture. Naloxone alone, added before the first tests with CCK-8, never contracted the tissues. The height of these first test responses to nor-binaltorphimine and naloxone were roughly related to the CCK-8 concentration. At CCK-8 0.08–2×10−9 M, the selective μ-antagonist, cyprodime (1.4×10−6 M), evoked no response in 70% of tissues and a very weak response (lower than 10% of ACh maximum) in the others (Figure 1 and Table 1); at CCK-8 10−8 M, five out of six tissues responded to cyprodime but the response was still weak (Table 1). Cyprodime-induced contractures were significantly less intense than the responses to naloxone and nor-binaltorphimine and remained unchanged by κ-opioid receptor blockade (achieved by adding nor-binaltorphimine, 1.1 or 3.4×10−8 M, 1 or 5 min before CCK-8).

Figure 1.

Contractile responses to opioid antagonists in isolated GPI preparations pre-contracted with CCK-8. Tissue preparations were exposed to CCK-8 (2×10−9 M). Naloxone (N; 5.4×10−7 M), the selective μ-opioid antagonist, cyprodime (CYP; 1.4×10−6 M) and the selective κ-antagonist, nor-binaltorphimine (BNI; 3.4×10−8 M) were added at the declining tonic response to CCK-8. The tracings were recorded from three tissue preparations obtained from the same animal.

Table 1.

Contractures of isolated guinea-pig ileum in response to CCK-8 and to opioid antagonists, added at the declining tonic response to CCK-8

In the second CCK-8/antagonist tests, the responses to nor-binaltorphimine and naloxone were significantly reduced (by 42% at CCK-8 2×10−9 M); in the third and further tests responses remained statistically unchanged. Tonic responses to CCK-8 maintained their intensity throughout all tests (data not shown). Mu-receptor blockade by cyprodime (4.5 and 14×10−7 M), added 1 or 5 min before CCK-8, did not alter the response to nor-binaltorphimine in the first test nor did it prevent the second test reduction (not shown).

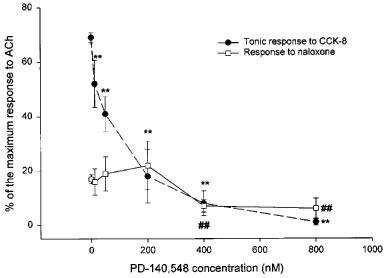

The CCKA antagonist PD-140,548 (1.2–80×10−8 M) added 5 min before CCK-8, dose-dependently reduced the phasic and tonic responses to CCK-8 4×10−10 M; the highest antagonist concentrations also reduced significantly the first test response to naloxone (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of the selective CCKA antagonist, PD-140,548, on the tonic response to CCK-8 and on the subsequent response to naloxone of isolated GPI preparations. Tissue preparations were first tested with CCK-8 (4×10−10 M). In subsequent tests the CCKA antagonist, PD-140,548 (1.2–80×10−8 M) was added 5 min before CCK-8. Naloxone (5.4×10−7 M) was added 2 min after CCK-8. Contractures are expressed as percentages of maximum response to ACh. The values shown are means±s.e.mean. For each PD-140,548 concentration, 6–10 tissue preparations from three animals were used (for controls, 24 tissue preparations from six animals). **P<0.01 vs control tonic response to CCK-8; ##P<0.01 vs control response to naloxone.

The CCKB antagonist, L-365,260 (1.2×10−9–10−6 M) significantly (P<0.05, n=5) inhibited by 35% the tonic response to CCK-8 only when the highest antagonist concentration was tested; at all concentrations, L-365,260 failed to cause significant changes of the first test response to naloxone (not shown).

Similarly, the two antagonists combined (PD-140,548; 2×10−7 M; L-365,260: 2.5×10−7 M) failed to reduce the naloxone-induced contractures and reduced the CCK-8-induced tonic responses to the same extent as the CCKA antagonist alone (not shown).

Opioid effects on CCK-8 contractures and the responses to naloxone or selective μ- or κ-antagonists in tissues exposed to dermorphin or U-50,488H and CCK-8; changes in opioid effects in repeated opioid agonist/CCK-8/opioid antagonist tests

The selective μ-opioid agonist, dermorphin (1.2–24×10−9 M), added to the bath 2 min before CCK-8, inhibited the contractile response of the ilea to CCK-8 (2×10−9 M) and increased the responses to cyprodime (1.4×10−6 M) and naloxone (5.4×10−7 M). The two effects differed in their time-course because in consecutive dermorphin/CCK-8/cyprodime tests the inhibition of the tonic response to CCK-8 remained unvaried whereas the response to cyprodime increased in intensity up to the third test and thereafter remained constant (Figure 3). The response to naloxone in consecutive dermorphin/CCK-8/naloxone tests increased in a similar manner (data not shown). The increase of the response to cyprodime or naloxone was observed at all dermorphin concentrations. The concentration-response curves for the two effects also differed: the lowest dermorphin concentration (1.2×10−9 M) left the tonic response to CCK-8 statistically unchanged but increased the response to naloxone (Figure 4a; the values shown in the figure are those obtained in the third dermorphin/CCK-8/naloxone tests) and cyprodime (data not shown). At all dermorphin concentrations the responses to cyprodime were 15–20% lower than those to naloxone, but the difference never reached statistical significance. Cyprodime (1.4–14×10−7 M), added 1 min before the μ-agonist antagonised in a concentration-related way dermorphin-induced inhibition of the tonic response to CCK-8 and dermorphin-induced increase in the antagonist response (not shown).

Figure 3.

Isolated GPI responses to CCK-8 (tonic contracture) and cyprodime in repeated dermorphin/CCK-8/cyprodime tests. Each tissue preparation was first tested with CCK-8 (2×10−9 M) and cyprodime (1.4×10−6 M). Thereafter, five tests with dermorphin/CCK-8/cyprodime (dermorphin: 1.2×10−8 M; CCK-8: 2×10−9 M; cyprodime: 1.4×10−6 M) were performed. After each test, tissue preparations were washed three times and allowed to rest for 30 min before next test. Contractures are expressed as percentages of the maximum response to ACh. The values shown are the means (±s.e.mean) from nine tissue preparations coming from five animals. **P<0.01 vs Test I (one-way ANOVA for repeated measures, followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test).

Figure 4.

Concentration-response curves of dermorphin (a) and U-50, 488H (b) for inhibition of the tonic response to CCK-8 and the increase of the response to naloxone in GPI preparations. Tissue preparations were first tested with CCK-8 (2×10−9 M) and naloxone (5.4×10−7 M), added 2 min after CCK-8. In subsequent tests, opioid agonists were added 2 min before CCK-8 (2×10−9 M); naloxone (5.4×10−7 M) was added 2 min after CCK-8. Contractures are expressed as percentages of the maximum response to ACh. The values shown are the means (±s.e.mean) of 6–12 experiments (n=42 for controls). For the dermorphin concentration-response curve, 24 tissue preparations coming from six animals were used (one or two dermorphin concentrations were tested on each preparation). For the U-50,488H curve, 18 preparations coming from six animals were used (two or three U-50,488H concentrations were tested on each preparation). **P<0.01 vs control tonic response to CCK-8; ##P<0.01 vs response to naloxone in the CCK-8/naloxone tests.

In tissue preparations exposed to dermorphin 6×10−9 M, κ-receptor blockade by nor-binaltorphimine (3.4×10−8 M), added 1 min before cyprodime in the fourth or further dermorphin/CCK-8/cyprodime tests (i.e., when the response to the μ-antagonist remained stable), did not significantly increase the withdrawal response to the μ-antagonist (not shown). Although nor-binaltorphimine significantly increased the response to cyprodime in the third dermorphin/CCK-8/cyprodime test – designed to test the effect of a κ-blockade before the response to the μ-antagonist had stabilized–the increase did not significantly exceed that usually occurring in control tissues (two-way ANOVA for repeated measures showed no significant interaction between the increase from test II to test III and the presence of nor-binaltorphimine). Nor-binaltorphimine itself also caused a slight contraction (18±5.1% of maximum ACh intensity, mean±s.e.mean, n=9).

The selective κ-agonist, U-50,488H (5.4–107.4×10−9 M), added to the bath 2 min before CCK-8, also dose-dependently inhibited the tonic contracture to CCK-8 (2×10−9 M) and increased the responses to nor-binaltorphimine (3.4×10−8 M) and naloxone (5.4×10−7 M). In consecutive U-50,488H/CCK-8/nor-binaltorphimine tests the response to the antagonist decreased from test I to test II, but the difference was not statistically significant, and remained unchanged in subsequent tests; the inhibition of the tonic response to CCK-8 remained unvaried (data not shown). The concentration-response curves for the two effects differed: the lowest U-50,488H concentration (5.4×10−9 M) left the tonic response to CCK-8 unchanged but markedly increased the response to nor-binaltorphimine (data not shown) and naloxone (Figure 4b). The responses to nor-binaltorphimine were about 15% higher than those to naloxone but the difference never reached statistical significance. The effects of U-50,488H were antagonized by nor-binaltorphimine (2.8–11×10−8 M), added 1 min before the κ-agonist (not shown).

Cyprodime (1.4×10−6 M) added 1 min before the κ-antagonist failed to alter the response to nor-binaltorphimine (data not shown).

The withdrawal responses to naloxone and to the selective μ- or κ-antagonists had the same intensity regardless of whether the antagonists were added at the declining tonic response to CCK-8 or 8 min after CCK-8, i.e. when the response to CCK-8 without opioid agonists had faded (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Dermorphin (D, 3×10−9 M), added to the bath 2 min before CCK-8 (2×10−9 M), increases the response to naloxone (N; 5.4×10−7 M) of isolated guinea-pig ilea pre-contracted with CCK-8. The response to naloxone had the same intensity regardless of whether the antagonist was added at the declining tonic response to CCK-8 or 8 min after CCK-8, i.e. when the response to CCK-8 had faded. The tracings were obtained from the same tissue preparation.

CCK-8 enhancement of the withdrawal responses to naloxone in GPI tissues exposed to μ- or κ-agonists

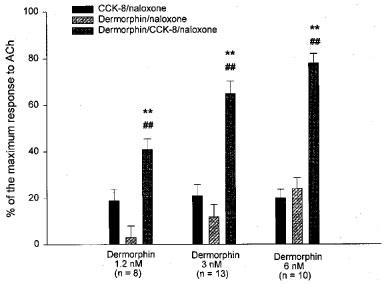

In tissue preparations exposed for 5 min to the selective μ-agonist dermorphin (1.2–6×10−9 M) alone, the addition of naloxone (5.4×10−7 M) caused a very weak withdrawal response or no response at all. In subsequent tests using the same preparations, the addition of CCK-8 (0.4–10×10−9 M), 2 min after the opioid agonist caused the naloxone-induced contracture to appear or markedly increase (Figures 6 and 7). Responses to naloxone were concentration-related to dermorphin (Figure 7) but not to CCK-8, either in tissues pre-exposed to dermorphin 1.2×10−9 M (not shown) or 3×10−9 M (Table 2).

Figure 6.

A typical tracing showing that CCK-8 (4×10−10 M) strongly enhances the withdrawal response to naloxone (N; 5.4×10−7 M) after exposure to dermorphin (D; 1.2×10−9 M). The tracings were obtained from the same tissue preparation. After a first test with CCK-8/naloxone (CCK-8: 4×10−10 M; naloxone: 5.4×10−7 M), the preparation was exposed to dermorphin (1.2×10−9 M) for 5 min and then challenged with naloxone (5.4×10−7 M). In the subsequent test, the tissue preparation was exposed to dermorphin (1.2×10−9 M) and CCK-8, added 2 min after dermorphin; naloxone (5.4×10−7 M) was added at the declining tonic contraction to CCK-8.

Figure 7.

Responses to naloxone following exposure to dermorphin in absence or presence of CCK-8 (2×10−9 M). The preparations were first tested with CCK-8/naloxone (CCK-8: 2×10−9 M; naloxone: 5.4×10−7 M). Tissue preparations were then exposed to dermorphin (1,2, 3 or 6×10−9 M) for 5 min and then challenged with naloxone (5.4×10−7 M). In the subsequent test, tissue preparations were exposed to dermorphin (same concentration as in the first test) and CCK-8, added 2 min after dermorphin; naloxone (5.4×10−7 M) was added at the declining tonic contraction to CCK-8. Contractures are expressed as percentages of ACh maximum. Values shown are means±s.e.mean. The number of tissue preparations tested for each dermorphin concentration is shown in brackets. Tissue preparations came from six animals. **P<0.01 vs the response to naloxone in dermorphin/naloxone tests; ##P<0.01 vs the response to naloxone in the CCK-8/naloxone tests (one-way ANOVA for repeated measures, followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test).

Table 2.

Responses to naloxone (NLX) after exposure to dermorphin, with increasing CCK-8 concentrations

In isolated GPI exposed to the selective κ-agonist, U-50,488H (5.4×10−9 M), the addition of naloxone (5.4×10−7 M) caused no response in 13 out of 15 tissue preparations and a weak response in the others. CCK-8 (0.4–10×10−9 M), added 2 min after the opioid agonist, caused the naloxone-induced contracture to appear or markedly increase. All CCK-8 concentrations tested induced a similar increase (data not shown).

The CCKA antagonist, PD-140,548 (1 and 8×10−7 M) reduced the response to naloxone in dermorphin/CCK-8/naloxone tests (dermorphin: 1.2×10−9 M; CCK-8: 4×10−10 M) only at its highest concentration; with both antagonist concentrations the tonic response to CCK-8 was almost completely inhibited (Table 3). The CCKB antagonist, L-365,260 (2.5 and 10×10−6 M), only caused a 41% inhibition of the tonic response to CCK-8 (P<0.05 vs controls, n=5), at its highest concentration, but left the response to naloxone unchanged (data not shown).

Table 3.

Effect of the CCKA antagonist, PD-140,548 (PD), on the CCK-8-induced enhancement of the response to naloxone (NLX) following exposure to dermorphin (D) and on the tonic response to CCK-8

Discussion

The contractile response of GPI preparations to CCK-8 consists of two components: a rapid phasic response, which appeared to be preferentially mediated by CCKB receptors (Dal Forno et al., 1992), and a slower tonic response, which appears to be mediated by CCKA receptors (Dal Forno et al., 1992; Corsi et al., 1994). Both responses are neuronally mediated; the phasic response depends almost exclusively on the release of ACh from cholinergic neurons while the tonic response apparently also depends on the release of Substance P (Lucaites et al., 1991; Corsi et al., 1994).

The first evidence showing that CCK-8 activated the isolated GPI opioid system came from the observation that the addition of naloxone to CCK-8 exposed tissues induced a contracture, which depended on ACh release, because it was abolished by tetrodotoxin and atropine (Garzon et al., 1987; Valeri et al., 1990b). The height of the contracture was related to the CCK-8 concentration and pretreating tissues with naloxone before CCK-8 prevented its occurrence. Naloxone also induced a contracture in GPI pre-contracted with other indirect excitatory peptides, including bombesin, corticotropin-releasing factor, and neurotensin (Garzon et al., 1987). The naloxone-induced response was attributed to the presence of an opioid substance, released to counterbalance the excitatory effect of neurally acting peptides. Accordingly, peptides acting directly on the smooth muscle (substance P, bradykinin, and angiotensin II) elicited only small naloxone-induced contractures (Garzon et al., 1987). In this study we found that GPI preparations exposed to CCK-8 0.08–10×10−9 M contracted to the addition of the selective κ-antagonist, nor-binaltorphimine, and the non-selective antagonist, naloxone. On the other hand, the selective μ-antagonist, cyprodime contracted only tissues exposed to CCK-8 10−8 M and the response was much weaker than that to nor-binaltorphimine and naloxone. At these concentrations, cyprodime and nor-binaltorphimine are selective because cyprodime (1.4×10−6 M) evoked a withdrawal contracture only in the tissue preparations exposed to the μ-agonist, dermorphin, and, conversely, nor-binaltorphimine (3.4×10−8 M) evoked a withdrawal contracture only in the preparations exposed to the κ-agonist, U-50,488H (Valeri et al., 1996). Hence, CCK-8 appears to activate preferentially the κ-opioid receptor system in isolated GPI. Evidence that CCK-8 also activates the κ-opioid receptor system in the brain comes from earlier studies showing that intracerebroventricular injection of CCK-8 reduces the colonic motor inhibition induced by rectal distension, a reduction reversed by nor-binaltorphimine (Gue et al., 1995). CCK-8 also increases the release of the endogenous κ-agonist, dynorphin B, in various brain areas (You et al., 1996; 1997). CCK-8-induced release of an endogenous κ-agonist may be responsible for the tachyphylaxis developing to the contractile effect of excitatory peptides in unwashed GPI preparations (Garzon et al., 1987). Yet, in our second CCK-8/antagonist test, after the washout between the first and second tests, the contractures to naloxone and nor-binaltorphimine markedly weakened whereas the responses to CCK-8 retained their intensity. These findings suggest that CCK-8 exposure may also initiate intracellular events thus selectively and partially reducing the response to the antagonists. Cross-talk between CCK and opioid receptors has already been suggested to explain the CCK/opioid interactions observed in some in vitro studies (Miller & Lupica, 1994; Liu et al., 1995; Xu et al., 1996). In addition, CCK-8 reduces the available κ-opioid binding sites in brain homogenates (Wang & Han, 1990).

Our study confirms that CCKA receptors are responsible for tonic contraction to CCK-8 and suggests that these receptors may also be responsible for κ-activation, because only the selective CCKA antagonist (Boden et al., 1993; Singh et al., 1995) PD-140,548, but not the selective CCKB antagonist (Lotti & Chang, 1989) L-365,260, reduced the CCK-8-induced response to naloxone. Data from binding studies suggest that at the concentrations inhibiting the response to naloxone, PD-140,548 may also occupy CCKB receptors (Suman-Chauhan et al., 1996). Yet, the complete absence of any effect of the CCKB antagonist and of the two antagonists combined on the response to naloxone strongly suggests that CCKB receptors do not play a role in the κ-opioid system activation.

It has been shown that the CCKA receptor can exist in three affinity states (Huang et al., 1994; Talkad et al., 1994) and that some CCKA antagonists have a preferential affinity for one of these affinity states (Huang et al., 1994; Talkad et al., 1994; Taniguchi et al., 1996). Taken together, these data may explain our finding that the concentrations of PD-140,548 inhibiting the response to naloxone were higher than those inhibiting the tonic response to CCK-8. We found that a maximal tonic contracture occurred with CCK-8 2×10−10 M while the responses to nor-binaltorphimine and naloxone increased up to CCK-8 10−8 M (see Table 1). Hence, CCK-8-induced tonic contracture and κ-opioid system activation may be mainly mediated through different CCKA receptor affinity states. The data of Singh and co-workers (1995) suggest that the CCKA antagonist used in our study, PD-140,548, may interact preferentially with the high-affinity CCKA receptor state, because the antagonist inhibited the CCK-8-induced contraction of guinea-pig gallbladder – a response probably mediated by the low-affinity state of CCKA receptor (Taniguchi et al., 1995) – with a functional affinity 30 fold lower than its binding affinity in the pancreas, where the high affinity state predominates (Taniguchi et al., 1995). Therefore, it is possible that PD-140,548 antagonised the tonic GPI contraction to CCK-8 at lower concentrations than those inhibiting the κ-activation because: (i) the two CCK-8 effects are mainly mediated through different CCKA receptor affinity states; and, (ii) the CCKA antagonist preferentially occupied the affinity state mediating the tonic response.

In our experiments, pretreating isolated GPI tissues with the selective μ- or κ-opioid agonists decreased the response to CCK-8, probably owing to opioid inhibition of ACh release (Cherubini et al., 1985; Cherubini & North, 1985). Opioid agonists also increased the contractures to the respective antagonist or to the non-selective antagonist naloxone. Several observations indicate that these contractures are opioid withdrawal responses. First, they were related to the opioid agonist concentration. Second, the opioid agonists markedly increased the responses to the opioid antagonists at concentrations lower than those inhibiting the CCK-8-induced contraction. Hence, ACh release by CCK-8 (which was still present in the bath when the opioid antagonists were added) did not contribute substantially to the antagonist-induced contracture. Finally, earlier studies had shown that the antagonist-induced response in tissues exposed to opioid agonists and CCK-8 was inhibited by clonidine, nifedipine (Valeri et al., 1990b) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Valeri et al., 1993). It therefore had the same pharmacological characteristics as the withdrawal response obtained in tissues exposed to opioid agonists alone (Chahl, 1985; Borrios & Baeyens, 1988; Johnson et al., 1988; Valeri et al., 1990a).

In this study, we found that the withdrawal contracture to the μ-opioid antagonist, cyprodime, first increased and in subsequent opioid agonists/CCK-8/opioid antagonists tests retained its intensity; whereas previous studies had shown that in tests with μ-(or κ-)opioid agonists/antagonists the withdrawal response declined rapidly (Chahl, 1990; Cruz et al., 1991; Brent et al, 1993; Valeri et al., 1996). This suggests that CCK-8 prevents the progression of tolerance to the μ-withdrawal response in isolated GPI. The stable response to the κ-antagonist, nor-binaltorphimine (or to naloxone) in subsequent U-50,488H/CCK-8/opioid antagonist tests shows that CCK-8 also prevents the development of tolerance to the κ-withdrawal response.

In antagonizing tolerance, CCK-8 may depress a neuronal activity inhibiting the withdrawal response. In a previous work, we found that stimulation of the μ-opioid system with selective agonists indirectly activated the κ-system, which in turn inhibited the μ-system withdrawal response, and vice versa (Valeri et al., 1996). In this study, κ-blockade failed to increase the response to cyprodime in dermorphin/CCK-8/cyprodime tests and, conversely, μ-blockade failed to increase the response to nor-binaltorphimine in the U-50,488H/CCK-8/nor-binaltorphimine tests. Hence, in CCK-8 exposed GPI tissues this μ/κ interaction did not operate.

Our study clarifies the question of how CCK-8 affects the withdrawal response in isolated GPI. CCK-8 clearly enhanced the antagonist-induced withdrawal response in tissue preparations briefly exposed to both μ- and κ-agonists. Yet, only the κ-antagonist, nor-binaltorphimine, elicited a response after exposure to CCK-8. In addition, CCK-8 4×10−10 M dramatically increased the intensity of the withdrawal response but higher concentrations induced no further increase. These findings strongly suggest that CCK-8 increased the μ- and κ-withdrawal response not through an additive effect but by reinforcing the expression of acute dependence. This effect also appears to be mediated by CCKA receptors. Data from in vivo studies have shown that both CCK agonists and antagonists reduce naloxone-precipitated withdrawal signs in morphine-dependent mice (Zarrindast et al., 1995). Similar conflicting results come also from antinociception studies (reviewed by Cesselin, 1995). Hence, as often observed in studies focusing on the interactions between opioids and CCK, also the effect of CCK on opioid withdrawal may very critically depend on the opioid and CCK doses used. We found that CCK-8 never inhibited the withdrawal response to opioid agonists in a range of concentrations (10−10–10−8 M). Therefore, in isolated GPI, CCK-8 appears to invariably enhance the expression of the μ- and κ-withdrawal response. This enhancement contrasts with the CCK-8-induced activation of the κ-opioid system because κ-activation should in theory prevent the μ-withdrawal response. Presumably the enhancement of the μ-withdrawal response overwhelms the inhibition induced by κ-activation . A possible mechanism for the CCK-8 enhancing effect of μ- and κ-withdrawal responses is the CCK-8/opioids interaction at the Ca2+ current level. Recent studies have shown that – as well as κ-opioid agonists – μ-agonists inhibit Ca2+ currents (Rhim & Miller, 1994; Mima et al., 1997; Rusin & Moises, 1998; Soldo & Moises, 1998) and that CCK-8 can reverse μ-receptor- and κ-receptor-mediated inhibition of Ca2+ current (Liu et al., 1995; Xu et al., 1996). CCK-8 could therefore (partially) antagonize the opioid-induced inhibition of the activity of some neurons in GPI tissue preparations exposed to opioids, thus facilitating one or more steps in the chain of events leading to tissue opioid dependence.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by ‘Fondazione Enrico ed Enrica Sovena', Rome, Italy.

Abbreviations

- CCK

cholecystokinin

- CCK-8

cholecystokinin octapeptide sulphate

- GPI

guinea-pig ileum

References

- BODEN P.R., HIGGINBOTTOM M., HILL D.R., HORWELL D.C., HUGHES J., REES D.C., ROBERTS E., SINGH L., SUMAN-CHAUMAN N., WOODRUFF G.N. Cholecystokinin dipeptoid antagonists: Design, synthesis and anxiolytic profile of novel CCK-A and CCK-B selective and ‘mixed' CCK-A/CCK-B antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 1993;36:552–565. doi: 10.1021/jm00057a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BORRIOS M., BAEYENS J.M. Differential effects of calcium channel blockers and stimulants on morphine-withdrawal in vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1988;152:175–178. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90852-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRENT P.G., CHAHL L.A., CANTARELLA P.A., KAVANAGH C. The κ-opioid receptor agonist U-50, 488H induces acute physical dependence in guinea-pigs. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;241:149–156. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90196-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CESSELIN F. Opioid and anti-opioid peptides. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 1995;9:409–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1995.tb00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAHL L.A. The properties of the clonidine withdrawal response of guinea-pig isolated ileum. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1985;85:457–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb08882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAHL L.A. Withdrawal responses of guinea-pig isolated ileum following brief exposure to opiates and opioid peptides. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1986;333:387–392. doi: 10.1007/BF00500014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAHL L.A. Effects of putative neurotransmitters and related drugs on withdrawal contractures of guinea-pig isolated ileum following brief contact with (Met5) enkephalin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1990;101:908–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHERUBINI E., MORITA K., NORTH R.A. Opioid inhibition of synaptic transmission in the guinea-pig myenteric plexus. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1985;85:805–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb11079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHERUBINI E., NORTH R.A. Mu and kappa opioids inhibit transmitter release by different mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985;215:413–415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.6.1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORSI M., PALEA S., PIETRA C., OLIOSI B., GAVIRAGHI G., SUGG E., VAN AMSTERDAM F.T.M., TRIST D.G. A further analysis of the contraction induced by activation of cholecystokinin A receptors in guinea-pig isolated ileum longitudinal muscle-myenteric plexus. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;270:734–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRUZ S.L., SALAZAR L.A., VILLAREAL J.E. A methodological basis for improving the reliability of measurement of opiate abstinence responses in the guinea-pig ileum made dependent in vitro. J. Pharmacol. Meth. 1991;25:329–342. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(91)90032-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAL FORNO G., PIETRA C., URCIOLI M., VAN AMSTERDAM F.T.M., TOSON G., GAVIRAGHI G., TRIST D. Evidence for two cholecystokinin receptors mediating the contraction of the guinea-pig ileum longitudinal muscle myenteric plexus. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;261:1056–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DISSANAYAKE V.U.K., HUNTER J.K., HILL R.G., HUGHES J. Characterization of κ-opioid receptors in the guinea pig ileum. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990;182:73–82. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90494-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOURISH C.T., HAWLEY D., IVERSEN S.D. Enhancement of morphine analgesia and prevention of morphine tolerance in the rat by the cholecystokinin antagonist L-364,718. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1988;147:469–472. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARZON J., HOLLT V., SANCHEZ-BLAZQUES P., HERZ A. Neural activation of opioid mechanisms in guinea-pig ileum by excitatory peptides. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1987;240:642–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUE M., DEL RIO C., JUNIEN J.L., BUENO L. Interaction between CCK and opioids in the modulation of the rectocolonic inhibitory reflex in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;269:G240–G245. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.2.G240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUANG S.C., FORTUNE K.P., WANK S.A., KOPIN A.S., GARDNER J.D. Multiple affinity states of different cholecystokinin receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:26121–26126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUTCHINSON M., KOSTERLIZ H.W., LESLIE F.M., WATERFIELD A.A., TERENIUS L. Assessment in the guinea-pig ileum and mouse vas deferent of benzomorphans which have strong antinociceptive activity but do not substitute for morphine in the dependent monkey. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1975;55:541–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1975.tb07430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON M.A., HILL R.G., HUGHES J. A possible role for prostaglandins in the expression of morphine dependence in guinea-pig isolated ileum. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;93:932–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU N.J., XU T., XU C., LI C.Q., YU Y.X., KANG H.G., HAN J.S. Cholecystokinin octapeptide reverses μ-opioid-receptor-mediated inhibition of calcium current in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;275:1293–1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOTTI V.J., CHANG R.S.L. A new potent and selective non-peptide gastrin antagonist and brain cholecystokinin receptor (CCK-B) ligand: L-365,260. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;162:739–745. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUCAITES V.L., MENDELSOHN L.G., MASON N.R., COHEN M.L. CCK-8, CCK-4 and gastrin-induced contraction in guinea-pig ileum: Evidence for differential release of acetylcholine and Substance P by CCK-A and CCK-B receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;256:695–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUJAN M., RODRIGUEZ R. Pharmacological characterization of opiate physical dependence in isolated ileum of guinea-pig. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1981;73:859–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb08739.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALDONADO R., VALVERDE O. , DERRIEN M., TEJEDOR-REAL P., ROQUES B.P. Effects induced by BC 264, a selective agonist of CCK-B receptors, on morphine-dependent rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1994;48:363–369. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALDONADO R., VALVERDE O., DUCOS B., BLOMMAERT A.G., FOURNIE-ZALUSKI M.C., ROQUES B.P. Inhibition of morphine withdrawal by the association of RB 101, an inhibitor of enkephalin metabolism, and the CCKB antagonist PD-134,308. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:1031–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER K.K., LUPICA C.R. Morphine-induced excitation of pyramidal neurons is inhibited by cholecystokinin in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampal slice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;268:753–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIMA H., MORIKAWA H., FUKUDA K., KATO S., SHODA T., MORI K. Ca2+ channel inhibition by endomorphins via the cloned μ-opioid receptor expressed in NG108-15 cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;340:R1–R2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORRONE L.A., ROMANELLI L., AMICO M.C., VALERI P. Withdrawal contractures of guinea-pig isolated ileum after activation of κ-opioid receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;106:48–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PANERAI A.E., ROVATI L.C., COCCO E., SACERDOTE P., MANTEGAZZA P. Dissociation of tolerance and dependence to morphine: a possible role for cholecystokinin. Brain Res. 1987;410:52–60. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(87)80019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PORTOGHESE P.S., LIPKOWSKI A.W., TAKEMORI A.E. Binaltorphimine and nor-binaltorphimine, potent and selective κ-opioid receptor antagonists. Life Sci. 1987;40:1287–1292. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90585-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POURNAGHASH S., RILEY A.L. Failure of cholecystokinin to precipitate withdrawal in morphine-dependent rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1991;38:479–484. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90001-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REZAYAT M., ZARRINDAST M.R., AZIZI N. On the mechanism(s) of cholecystokinin (CCK): receptor stimulation attenuates morphine dependence in mice. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1997;81:124–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1997.tb00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RHIM H., MILLER R.J. Opioid receptors modulate diverse types of calcium channels in the nucleus tractus solitarius of the rat. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:7608–7615. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-12-07608.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSIN K.I., MOISES H.C. Mu-opioid and GABA(B) receptors modulate different types of Ca2+ currents in rat nodose ganglion neurons. Neuroscience. 1998;85:939–956. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00674-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMIDHAMMER H., BURKARD W.P., EGGESTEIN-AEPPLI L., SMITH C.F.C. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 14-alkoxymorphinans. 2. (−)-N-(cyclopropylmethyl)-4,14-dimeth-oxymorphinan-6-one, a selective μ-opioid antagonist. J. Med. Chem. 1989;32:418–421. doi: 10.1021/jm00122a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINGH L., FIELD M.J., HILL D.R., HORWELL D.C., MCKNIGHT A.T., ROBERTS E., TANG K.W., WOODRUFF G.N. Peptoid CCK receptor antagonists: pharmacological evaluation of CCKA, CCKB and mixed CCKA/B receptor antagonists. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;286:185–191. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00445-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOLDO B.L., MOISES H.C. Mu-opioid receptor activation inhibits N- and P-type Ca2+ channel currents in magnocellular neurones of the rat supraoctic nucleus. J. Physiol. (London) 1998;513:787–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.787ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUMAN-CHAUHAN N., MEECHAM K.G., WEDBALE L., HUNTER J.C., PRITCHARD M.C., WOODRUFF G.N., HILL D.R. The influence of guanyl nucleotide on agonist and antagonist affinity at guinea-pig CCK-B/gastrin receptors: Binding studies using [3H] PD140376. Regul. Pept. 1996;65:37–43. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(96)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TALKAD V.D., PATTO R.J., METZ D.C., TURNER R.J., FORTUNE K.P., BHAT S.T., GARDNER J.D. Characterization of the three different states of the cholecystokinin (CCK) receptor in pancreatic acini. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1221:103–116. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANIGUCHI H., NAGASAKI M., TAMAKI H. Effects of cholecystokinin (CCK)-JMV-180 on the CCK receptors of rabbit pancreatic acini and gallbladder smooth muscle. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1995;67:219–224. doi: 10.1254/jjp.67.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANIGUCHI H., YAZAKI N., ENDO T., NAGASAKI M. Pharmacological profile of T-0362, a novel potent and selective CCKA receptor antagonist, in vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996;304:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALERI P., MARTINELLI B., MORRONE L.A., SEVERINI C. Reproducible withdrawal contractions of isolated guinea-pig ileum after brief morphine exposure: effects of clonidine and nifedipine. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1990a;42:115–120. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1990.tb05364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALERI P., MORRONE L.A., PIMPINELLA G., ROMANELLI L. Some pharmacological characteristics of guinea-pig ileum opioid system activated by cholecystokinin. Neuropharmacology. 1990b;29:231–236. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(90)90006-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALERI P., MORRONE L.A., ROMANELLI L., AMICO M.C. Effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on withdrawal responses in guinea-pig ileum after a brief exposure to morphine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993;264:1028–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALERI P., ROMANELLI L., MORRONE L.A., AMICO M.C., MATTIOLI F. Mu and Kappa opioid system interactions in the expression of acute opioid dependence in isolated guinea-pig ileum. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:377–384. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG X.J., HAN J.S. Modification by cholecystokinin octapeptide of the binding of μ-, δ- and κ-opioid receptors. J. Neurochem. 1990;55:1379–1382. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb03149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XU X., WIESENFELD-HALLIN Z., HUGHES J., HORWELL D.C., HOKFELT T. CI988, a selective antagonist of cholecystokininB receptors, prevents morphine tolerance in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;105:591–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb09024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XU T., LIU N.J., LI C.Q., SHANGGUAN Y., YU Y.X., KANG H.G., HAN J.S. Cholecystokinin octapeptide reverses the κ-opioid-receptor-mediated depression of calcium current in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain Res. 1996;730:207–211. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOU Z.B., GODUKHIN O., GOINY M., NYLANDER I., UNGERSTEDT U., TERENIUS L., HOKFELT T., HERRERA-MARSCHITZ M. Cholecystokinin-8S increases dynorphin B, aspartate and glutamate release in the fronto-parietal cortex of the rat via different receptor subtypes. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1997;355:576–581. doi: 10.1007/pl00004986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOU Z.B., HERRERA-MARSCHITZ M., PETTERSSON E., NYLANDER I., GOINY M., SHOU H.Z., KEHR J., GODUKHIN O., HOKFELT T., TERENIUS L., UNGERSTEDT U. Modulation of neurotransmitter release by cholecystokinin in the neostriatum and substantia nigra of the rat: regional and receptor specificity. Neuroscience. 1996;74:793–804. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZARRINDAST M.R., MALEKZADEH A., REZAYAT M., GHAZI-KHANSARI M. Effect of cholecystokinin receptor agonist and antagonist on morphine dependence in mice. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1995;77:360–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1995.tb01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]