Abstract

The effects of various phorbol-based protein kinase C (PKC) activators on the electrical stimulation-induced (S-I) release of serotonin and acetylcholine was studied in rat brain cortical slices pre-incubated with [3H]-serotonin or [3H]-choline to investigate possible structure-activity relationships.

4β-Phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (4βPDB, 0.1–3.0 μM), enhanced S-I release of serotonin in a concentration-dependent manner whereas the structurally related inactive isomer 4α-phorbol 12, 13-dibutyrate (4αPDB) and phorbol 13-acetate (PA) were without effect. Another group of phorbol esters containing a common 13-ester substituent (phorbol 12,13-diacetate, PDA; phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, PMA; phorbol 12-methylaminobenzoate 13-acetate, PMBA) also enhanced S-I serotonin release with PMA being least potent.

The deoxyphorbol monoesters, 12-deoxyphorbol 13-acetate (dPA), 12-deoxyphorbol 13-angelate (dPAng), 12-deoxyphorbol 13-phenylacetate (dPPhen) and 12-deoxyphorbol 13-isobutyrate (dPiB) enhanced S-I serotonin release but 12-deoxyphorbol 13-tetradecanoate (dPT) was without effect. The 20-acetate derivatives of dPPhen and dPAng were less effective in enhancing S-I serotonin release compared to the parent compounds.

With acetylcholine release all phorbol esters tested had a far lesser effect when compared to their facilitatory action on serotonin release with only 4βPDB, PDA, dPA, dPAng and dPiB having significant effects.

The effects of the phorbol esters on serotonin release were not correlated with their reported in vitro affinity and isozyme selectivity for PKC. A comparison across three transmitter systems (noradrenaline, dopamine, serotonin) suggests basic similarities in the structural requirements of phorbol esters to enhance transmitter release with short chain substituted mono- and diesters of phorbol being more potent facilitators of release than the long chain esters. Some compounds notably PDA, PMBA, dPPhen, dPPhenA had different potencies across noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin.

Keywords: Phorbol esters, protein kinase C, serotonin release, acetylcholine release

Introduction

Phorbol esters have biological actions due to the activation of the protein kinase C (PKC) family of enzymes. These enzymes are activated physiologically by diacylglycerol and/or arachidonic acid and metabolites which are formed through various pathways after breakdown of membrane phospholipids (Stabel & Parker, 1991; Nishizuka, 1992). Some phorbol esters are tumour promoting whilst others act as anti-tumour agents (Zayed et al., 1984; Szallasi et al., 1993) and the rank orders of potency of different phorbol esters for various biological effects seems divergent. For example, the 12-deoxyphorbol esters are much weaker tumour promoters than would be expected from their skin irritant activity actions (Hergenhahn et al., 1974). Attempts have been made to explain this biological diversity through the differential activation of the various PKC isozymes by different phorbol esters (Ryves et al., 1991), differences in the ability of various phorbol esters to insert PKC into membranes (Kazanietz et al., 1992) and different PKC receptors for phorbol esters (Dunn & Blumberg, 1983). The explanation however may be more subtle since PKC is in a complex interaction with membrance phospholipids and the target substrate as well as the diacylglycerol/phorbol ester and the influence of these factors may only be evident in whole cell systems.

We previously described the structural requirements of phorbol esters to elevate electrical stimulation-induced noradrenaline and dopamine release from rat brain cortex slices in vitro (Kotsonis & Majewski, 1996). The potency and efficacy of phorbol esters in enhancing dopamine and noradrenaline release was not related to their reported affinities for PKC, their potency on isolated isozymes, their ability to insert PKC into membranes or their tumour promoting activity (see Kotsonis & Majewski, 1996). This suggests novel structural requirements. The present study was to extend these findings to two other transmitter systems in rat cortex: serotonin and acetylcholine.

Methods

Serotonin and acetylcholine release from rat cerebral cortex

Outbred Sprague-Dawley rats (140–250 g) were decapitated and the brains rapidly excised and placed in ice-cold physiological salt solution (PSS) previously gassed with a mixture of 5% CO2 and 95% O2. Slices from cerebral cortex (400 μm thick using Vibroslice 752, Campden Instruments) were incubated for 30 min in PSS maintained at 37°C and gassed with a mixture of 5% CO2 and 95% O2. This solution also contained the noradrenaline uptake inhibitor maprotiline (1 μM, serotonin incubation only), and [3H]-serotonin (3 μCi ml−1, 0.1 μM) or [3H]-choline (17 μCi ml−1, 0.2 μM). Following incubation, the slices were rinsed, transferred to flow cells and continuously superfused at 0.5 ml min−1 with PSS. In the case of the acetylcholine release experiments, the PSS contained hemicholinium-3 (10 μM) to prevent the reuptake of [3H]-choline back into the nerve terminals. The slices were superfused for 60 min before sample collection began (washing period). After 30 min of washing, an electrical priming stimulation was delivered through a pair of parallel platinum electrodes on either side of the brain slice (current strength 22 mA, square wave pulses of 2 ms duration at a frequency of 1 Hz for 60 s). After the washing period was completed, the collection period began in which the superfusate fractions were collected over consecutive 5 min periods for a total of 120 min. At 10, 55, 80 and 105 min after the commencement of the collection period, the cortical slices were stimulated (each at 1 Hz for 60 s, S1–S4). The effect of PKC activators on the electrical stimulation-induced outflow of radioactivity was determined by adding them in increasing concentrations to the superfusate solution 15 min before the second, third and fourth stimulation. At the completion of the experiments the cortical slices from the serotonin studies, were removed from the flow cells and placed in 0.5 ml Soluene (Packard Instruments, Melbourne, Australia) for 24 h to solubilize the tissue. The radioactivity present in the superfusate solution and brain slices were determined after the solutions were mixed with 3.0 ml Ultima Gold-XR (Packard Instruments, Melbourne, Australia) followed by liquid scintillation counting.

Long-term treatment with 4β-phorbol 12, 13-dibutyrate

Rat cortical brain slices were prepared as described previously. The slices were placed in 50 ml modified PSS containing 0.1 mM Ca2+, dextran (50 g l−1, average MW=70,000) and either 4β-phorbol 12, 13-dibutyrate (1 μM) or vehicle (dimethyl sulphoxide, DMSO 0.06% vv−1) in an open dish and maintained at 32°C in a tissue culture incubator for 20 h. The dextran was used to maintain oncotic pressure and the Ca2+ was lower than normal PSS to minimize possible toxic effects of Ca2+ over the 20 h period. The atmosphere of the incubator was a mixture of 5% CO2 and 95% O2. At the end of the 20 h incubation, the brain slices were removed from the culture medium and washed in 100 ml PSS. The slices were then incubated with [3H]-serotonin (3 μCi ml−1, 0.1 μM for 30 min) in normal PSS as previously described and then followed the identical protocol as described for acute experiments.

Calculation of results

The resting (spontaneous) outflow of radioactivity for each stimulation period was taken as the radioactive content of the bathing solution during the 5 min period immediately before and the 5 min period commencing 10 min after the start of the respective stimulation. The stimulation-induced (S-I) component of the outflow of radioactivity for S1–S4 was calculated by subtracting the resting radioactive outflow from the radioactive content of each of the two 5 min samples collected immediately after the commencement of each stimulation. For serotonin release, these values were then expressed as a ratio of the radioactivity present in the tissue at the onset of the stimulation (the fractional S-I outflow, FR). Drug effects on the S-I outflow of radioactivity were evaluated by comparing either the ratio of FR2/FR1, FR3/FR1 and FR4/FR1 or S2/S1, S3/S1 and S4/S1 for serotonin and acetylcholine release, respectively. The tissue level of radioactivity following [3H]-choline labelling is comprised of a variety of choline metabolites which makes the fractional S-I outflow calculation for acetylcholine release inappropriate.

Statistics

The values are given as mean and standard error of the mean (s.e.mean), n indicates the number of slices used; within each experimental group, the slices came from different animals and one experiment was performed on each tissue slice. The results were analysed with Scheffé's test after a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. Where appropriate two-way analysis of variance was also carried out to determine whether there was an interaction between the effects of the phorbol esters on transmitter release (A) and PKC down-regulation (B). In this case the significance was determined from an F-test on the interaction term A*B in the analysis of variance table. With regression analysis least squares regression was performed. In all cases, a probability of falsely concluding that two identical means are different (type 1 error) of less that 5% (P<0.05) was taken to indicate statistical significance. The statistical package GB-Stat (Dynamic Microsystems, Silver Spring, U.S.A.) was used for analysis.

Materials

The physiological salt solution (PSS) consisted of (mM): NaCl 118, KCl 4.7, KH2PO4 1.03, NaHCO3 25.0, D-(+)-glucose 11.1, MgSO4 1.2, CaCl2 1.3, ascorbic acid 0.14 and disodium EDTA 0.067.

Radiochemicals and drugs

Drugs used were hydroxytryptamine creatinine sulphate, 5- [1,2-3H(N)] (serotonin; specific activity 30 Ci/mmol) and choline chloride, [methyl-3H]- (specific activity 85.1 Ci/mmol) (DuPont NEN Products; Boston, U.S.A.); 4β-phorbol 12, 13-dibutyrate (4βPDB) and 4α-phorbol 12, 13-dibutyrate (4αPDB), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) were obtained from LC Laboratories (Woburn, U.S.A.); phorbol 13-acetate (PA), phorbol 12, 13-diacetate (PDA), phorbol 12, 13-triacetate (PTA), phorbol 12-methylaminobenzoate 13-acetate (PMBA, sapintoxin-D), 12-deoxyphorbol 13-acetate (dPA), 12-deoxyphorbol 13-angelate (dPAng), 12-deoxyphorbol 13-isobutyrate (dPiB), 12-deoxyphorbol 13-phenylacetate (dPPhen), 12-deoxyphorbol 13-tetradecanoate (dPT), 12-deoxyphorbol 13-phenylacetate 20-acetate (dPPhenA), 12-deoxyphorbol 13-angelate 20-acetate (dPAngA), thymeleatoxin (THYM), mezerein (MEZ), Sapphire Bioscience (Alexandria, Australia). Dextran and maprotaline were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, U.S.A.) and were dissolved and diluted with PSS. Stock solutions of the protein kinase C activators were initially made up in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) and stored at −20°C. On the day of the experiment these drugs were further diluted in PSS. Throughout the text all 12-deoxyphorbol and phorbol derivatives are of the 4β configuration except in the case of 4α-phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate. Control experiments were conducted with the corresponding concentration of DMSO (up to 0.18% v v−1).

Results

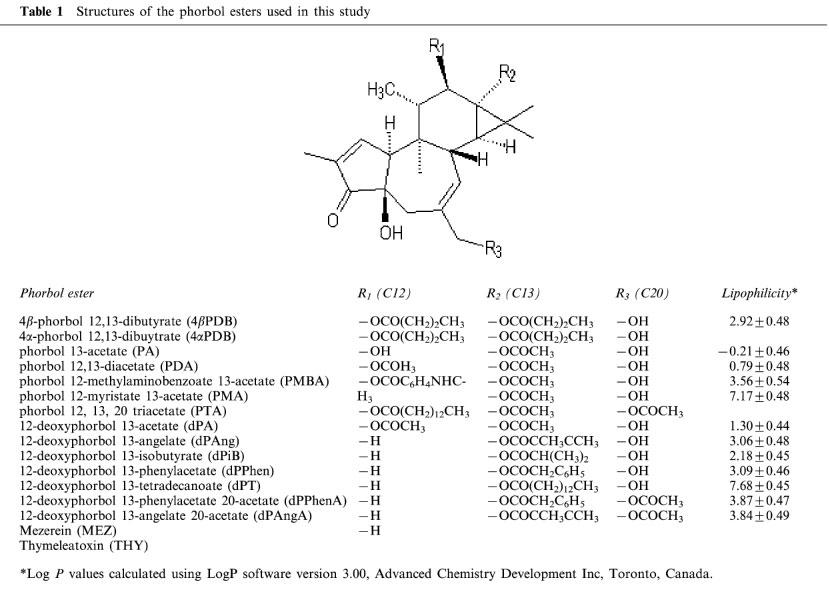

The structures and abbreviations used for all phorbol derived PKC activators are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Structures of the phorbol esters used in this study

[3H]-serotonin release from rat cerebral cortex

[3H]-serotonin was incorporated into the serotonergic transmitter stores of rat cerebral cortical slices and the electrical field stimulation evoked a stimulation-induced (S-I) outflow of radioactivity which was taken as an index of serotonin release. There were four periods of electrical stimulation (S1, S2, S3, S4 all at 1 Hz for 60 s) and the fractional S-I outflow in the first period (S1) was 0.009±0.002 (n=6), the fractional resting outflow immediately before S1 was 0.010±0.002 per 5 min (n=6) and the tissue radioactivity at the beginning of the sample collection was 643091±87378 d min−1 (n=6). Tetrodotoxin (0.3 μM) added for the second (S2) stimulation abolished the fractional outflow of radioactivity in the second stimulation (control FR2/FR1=0.77±0.02, n=6; tetrodotoxin FR2/FR1=0.00*±0.03, n=3; * significantly different from control, P<0.05, Student's t-test). This indicates that the S-I outflow involved the conduction of action-potentials. None of these treatments affected the resting outflow of radioactivity (not shown).

Effect of phorbol esters on serotonin release

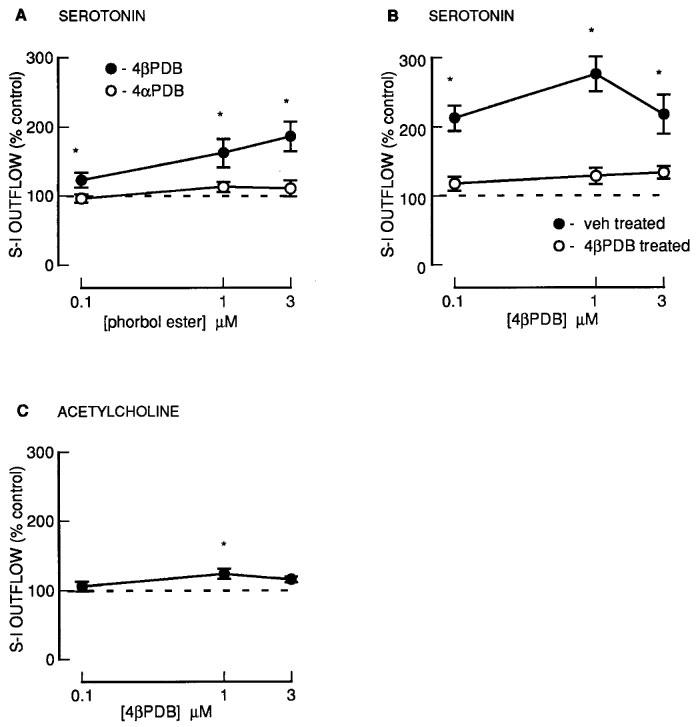

Concentration-response curves were constructed by superfusing tissue with increasing concentrations of phorbol esters during S2–S4. The phorbol 12, 13-diester, 4βPDB, enhanced the fractional S-I outflow of radioactivity during S2–S4 in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1A) whilst the structurally related but inactive isomer, 4αPDB, was without effect (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

The effect of phorbol esters on the fractional stimulation-induced (S-I) outflow of radioactivity from rat cortex slices pre-incubated with [3H]-serotonin or [3H]-choline. (A) [3H]-serotonin: fresh slices; (B) [3H]-serotonin: slices pre-incubated with 4βPDB (1 μM for 20 h) or vehicle (DMSO for 20 h); (C) [3H]-choline: fresh slices. There were four periods of electrical stimulation (each 1 Hz for 60 s) and drugs (4βPDB or 4αPDB) were present during the second, third and fourth stimulation in increasing concentrations. The S-I outflow in the second, third and fourth stimulation was expressed as a percentage of that in the first. All results are normalized such that control=100 (dashed line) for each stimulation period (x), thus the ratio of FRx/FR1 (serotonin) or Sx/S1 (acetylcholine) in the presence of drug was expressed as a percentage of the ratio of Frx/FR1 or Sx/S1 in the absence of drug (control series). Each symbol represents the mean and the vertical lines the standard error of the mean (s.e.mean). The number of experiments was between 4–10 for each drug. *Represents a significant difference from control, (P<0.05, Scheffé's test after two-way ANOVA).

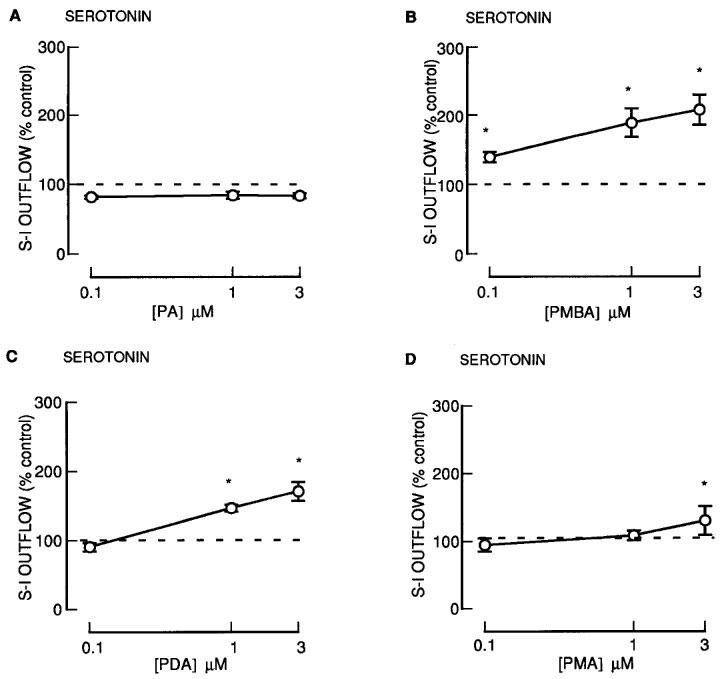

Another group of phorbol esters containing a common 13-acetate ester substituent: PDA, PMBA and PMA also enhanced the fractional S-I outflow of radioactivity during S2–S4 in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2). Phorbol 13-acetate (PA) was however without effect (Figure 2). For the phorbol 12, 13-diesters with a 13-acetate (PDA, PMBA, PMA), the degree of enhancement and the potency (Figure 2 and 6) was significantly less for PMA which had the largest 12-ester substituent (Table 1). None of these agents altered the resting outflow of radioactivity during S2–S4 (not shown).

Figure 2.

The effect of phorbol esters on the fractional stimulation-induced (S-I) outflow of radioactivity from rat cortex slices pre-incubated with [3H]-serotonin. There were four periods of electrical stimulation (each 1 Hz for 60 s) and drugs (PA; PMBA; PDA; PMA) were present during the second, third and fourth stimulation in increasing concentrations. All results are expressed as described in Figure 1 legend. Each symbol represents the mean and the vertical lines the standard error of the mean (s.e.mean). The number of experiments was between 5–8 for each drug. *Represents a significant difference from control, (P<0.05, Scheffé's test after two-way ANOVA).

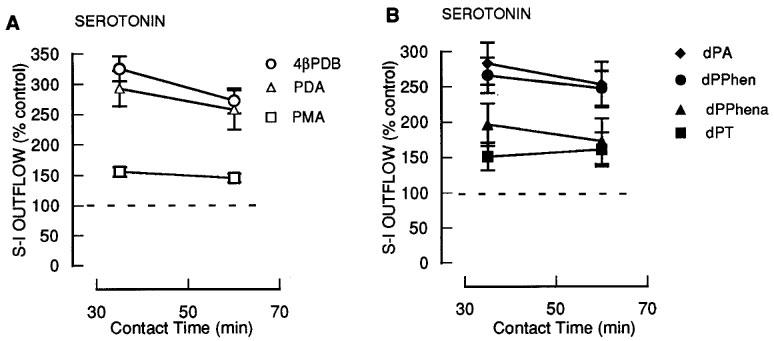

Figure 6.

The effect of prolonged exposure of phorbol and deoxyphorbol esters on the fractional stimulation-induced (S-I) outflow of radioactivity from rat cortex slices pre-incubated with [3H]-serotonin. There were four periods of electrical stimulation (each 1 Hz for 60 s) and drugs (4βPDB; PDA; PMA; dPA; dPPhen; dPPhenA; dPT) were present during the second, third and fourth stimulation in increasing concentrations. All results are expressed as described in Figure 1 legend. Each symbol represents the mean and the vertical lines the standard error of the mean (s.e.mean). The number of experiments was between 5–8 for each drug. *Represents a significant difference from control, (P<0.05, Scheffé's test after two-way ANOVA).

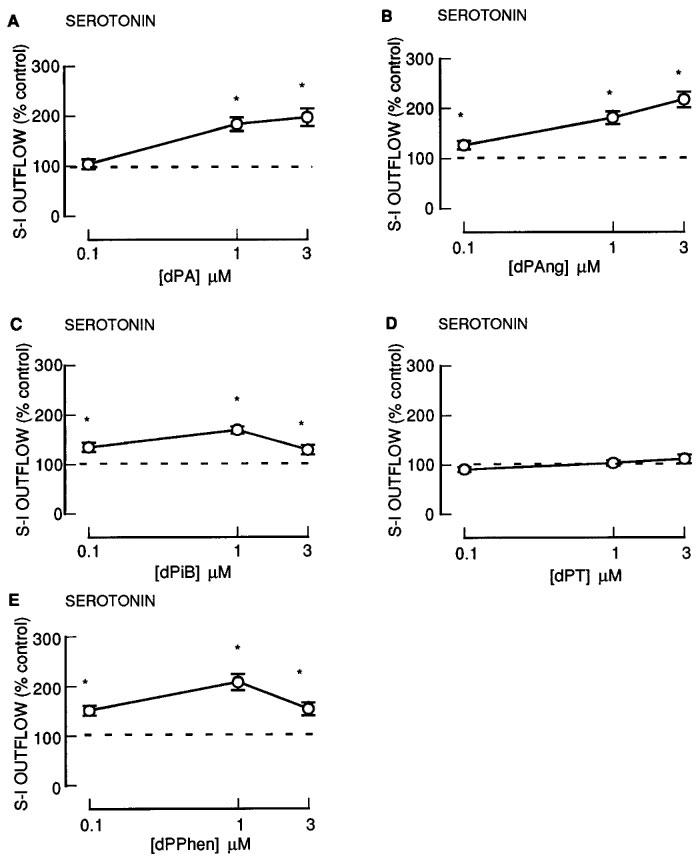

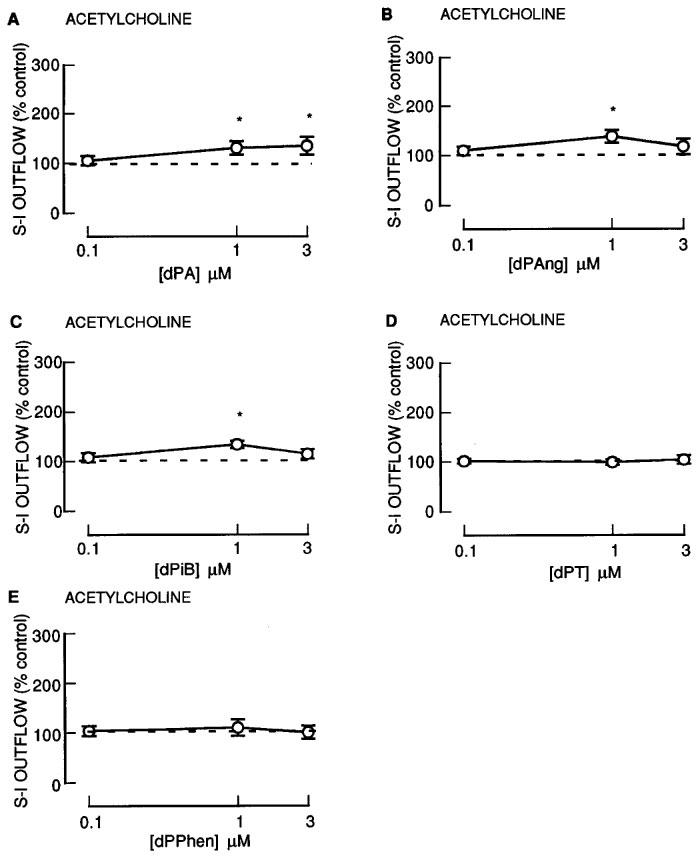

Effect of 12-deoxyphorbol esters on serotonin release

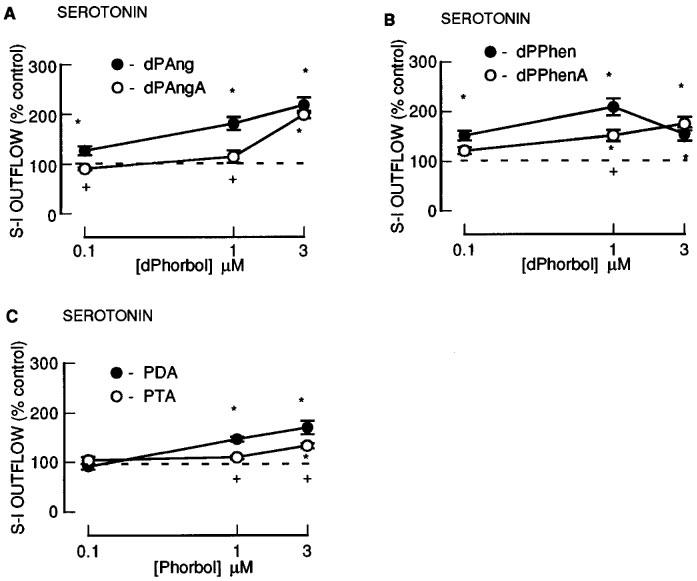

The 12-deoxyphorbol 13-monoesters: dPA, dPAng, dPiB, dPPhen, dPPhenA and dPAngA enhanced the fractional S-I outflow of radioactivity during S2–S4 in a concentration-dependent manner (Figures 3 and 4). In contrast, dPT which had the largest 13-ester substituent (Table 1) was without effect (Figure 3). None of these agents altered the resting outflow of radioactivity during S2–S4 (not shown). Twenty acetate substituted phorbol esters had a decreased facilitatory effect in comparison to their parent compounds (compare dPPhen with dPPhenA, dPAng with dPAngA and PDA with PTA; Figure 4).

Figure 3.

The effect of 12-deoxyphorbol 13-substituted mono-esters on the fractional stimulation-induced (S-I) outflow of radioactivity from rat cortex slices pre-incubated with [3H]-serotonin. There were four periods of electrical stimulation (each 1 Hz for 60 s) and drugs (dPA; dPAng; dPiB; dPT; dPPhen) were present during the second, third and fourth stimulation in increasing concentrations. All results are expressed as described in Figure 1 legend. Each symbol represents the mean and the vertical lines the standard error of the mean (s.e.mean). The number of experiments was between 4–8 for each drug. *Represents a significant difference from control, (P<0.05, Scheffé's test after two-way ANOVA).

Figure 4.

The effect of an additional 20-acetate group to phorbol esters on the fractional stimulation-induced (S-I) outflow of radioactivity from rat cortex slices pre-incubated with [3H]-serotonin. There were four periods of electrical stimulation (each 1 Hz for 60 s) and drugs (dPAng; dPAngA; dPPhen; dPPhenA; PDA; PTA) were present during the second, third and fourth stimulation in increasing concentrations (0.1, 1.0 and 3.0 μM). All results are expressed as described in Figure 1 legend. Each symbol represents the mean and the vertical lines the standard error of the mean (s.e.mean). The number of experiments was between 4–10 for each drug. *Represents a significant difference from control, (P<0.05, Scheffé's test after two-way ANOVA). +Represents a significant difference from the 20-acetate drugs (P<0.05, Scheffé's test after two-way ANOVA).

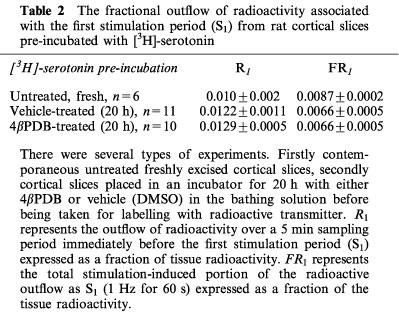

Effect of long-term treatment with 4βPDB on serotonin release

In order to down-regulate PKC, cortical slices were treated in modified PSS medium containing 0.1 mM Ca2+, dextran and either 4βPDB (1 μM) or vehicle (DMSO) for 20 h before being incubated with [3H]-serotonin. The vehicle did not affect the fractional S-I or resting outflow of radioactivity when compared to freshly excised cortical slices (compare vehicle-treated and untreated, Table 2). Compared to vehicle-treated tissues, 4βPDB treatment did not significantly alter the fractional S-I outflow and resting outflow of radioactivity (Table 2).

Table 2.

The fractional outflow of radioactivity associated with the first stimulation period (S1) from rat cortical slices pre-incubated with [3H]-serotonin

In rat cortical slices which were treated for 20 h with vehicle before incubation with [3H]-serotonin, 4βPDB enhanced the fractional S-I outflow of radioactivity (Figure 1B). However, when the slices were treated for 20 h in PSS with 4βPDB (1 μM), subsequent application of 4βPDB failed to enhance the fractional S-I outflow of radioactivity (Figure 1B).

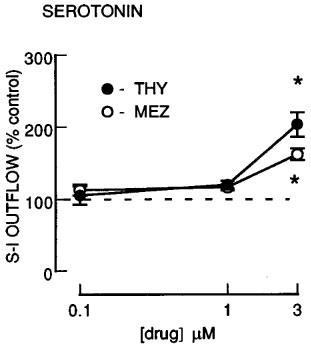

Effect of non-phorbol ester PKC activators on serotonin release

The non-phorbol ester PKC activators, mezerein and thymeleatoxin (0.1–3.0 μM), slightly enhanced S-I outflow of radioactivity at the highest concentration tested (3 μM) (Figure 5) without altering the resting outflow (not shown).

Figure 5.

The effect of non-phorbol ester PKC activators mezerein and thymeleatoxin on the fractional stimulation-induced (S-I) outflow of radioactivity from rat cortex slices pre-incubated with [3H]-serotonin. There were four periods of electrical stimulation (each 1 Hz for 60 s) and drugs (MEZ or THY) were present during the second, third and fourth stimulation in increasing concentrations. All results are expressed as described in Figure 1 legend. Each symbol represents the mean and the vertical lines the standard error of the mean (s.e.mean). The number of experiments was between 5–6 for each drug. *Represents a significant effect of drug on noradrenaline release from control (P<0.05, Scheffé's test after two-way ANOVA).

Effect of increasing contact time on ability of phorbol esters to enhance serotonin release

To test the possibility that the orders of potency observed were influenced by the contact time with the tissue in separate experiments we investigated the effects of different contact times for the 1 μM concentration of 4βPDB, PMA and PDA (Figure 6A) and dPT, dPPhen, dPPhenA and dPA (Figure 6B). In each case extending the contact time up to 60 min did not alter the orders of potency and these were the same as in the separate concentration studies.

Phorbol ester delivery to the tissue

Lipophilic drugs may in some cases bind to organ bath or flow cell apparatus and not reach the tissues to be tested. We decreased this likelihood by having teflon lined solvent paths and also directly tested this using [3H]-PDA, [3H]-PDB and [3H]-PMA. In all cases the phorbol esters reached the tissue at greater than 90% of their calculated concentration and furthermore the addition of bovine serum albumin to the phorbol esters solution, which aids in the carrying of lipophilic drugs in aqueous medium did not affect the concentration of phorbol ester reaching the tissue (not shown).

[3H]-choline release from rat cerebral cortex

[3H]-Choline was incorporated into the cholinergic transmitter stores of rat cerebral cortical slices in the presence of hemicholinium-3 and the electrical field stimulation evoked a stimulation-induced (S-I) outflow of radioactivity which was taken as an index of acetylcholine release. Both tetrodotoxin (0.3 μM) added for the second (S2) stimulation and Ca2+ removal, abolished S-I outflow of radioactivity in the second stimulation (control S2/S1=0.73±0.04, n=3; tetrodotoxin S2/S1=0.01*±0.01, n=4; Ca2+ removal S2/S1=0.00*±0.00, n=3. * significantly different from control, P<0.05, Student's t-test). None of these treatments affected the resting outflow of radioactivity (not shown).

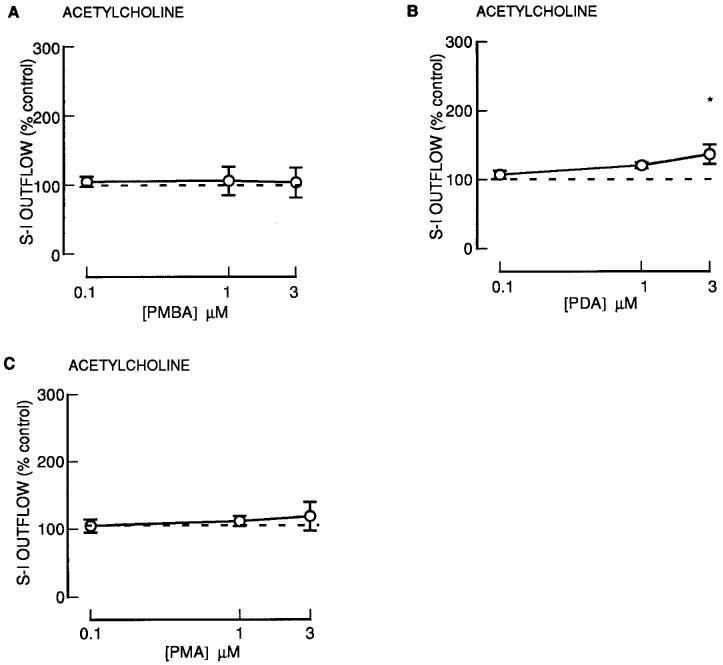

Effect of phorbol esters on acetylcholine release

Concentration-response curves were constructed by superfusing tissue with increasing concentrations of phorbol esters during S2–S4. 4βPDB, only slightly enhanced the S-I outflow of radioactivity during S2–S4 (Figure 1C).

Of the phorbol esters containing a common 13-acetate ester substituent, PMBA and PMA had no effect on S-I outflow of radioactivity during S2–S4, although PDA did have a small effect at the highest concentration tested (Figure 7). None of these agents altered the resting outflow of radioactivity during S2–S4 (not shown).

Figure 7.

The effect of phorbol esters on the stimulation-induced (S-I) outflow of radioactivity from rat cortex slices pre-incubated with [3H]-choline. There were four periods of electrical stimulation (each 1 Hz for 60 s) and drugs (PMBA; PDA; PMA) were present during the second, third and fourth stimulation in increasing concentrations. All results are expressed as described in Figure 1 legend. Each symbol represents the mean and the vertical lines the standard error of the mean (s.e.mean). The number of experiments was between 6–7 for each drug. *Represents a significant difference from control, (P<0.05, Scheffé's test after two-way ANOVA).

Effect of 12-deoxyphorbol esters on acetylcholine release

The 12-deoxyphorbol 13-monoesters: dPA, dPAng and dPiB, only slightly enhanced the S-I outflow of radioactivity during S2–S4 (Figure 8). In contrast, dPT and dPPhen were without effect (Figure 8). None of these agents altered the resting outflow of radioactivity during S2–S4 (not shown).

Figure 8.

The effect of 12-deoxyphorbol 13-substituted monoesters on the stimulation-induced (S-I) outflow of radioactivity from rat cortex slices pre-incubated with [3H]-choline. There were four periods of electrical stimulation (each 1 Hz for 60 s) and drugs (dPA; dPAng; dPiB; dPT; dPPhen) were present during the second, third and fourth stimulation in increasing concentrations. All results are expressed as described in Figure 1 legend. Each symbol represents the mean and the vertical lines the standard error of the mean (s.e.mean). The number of experiments was between 5–7 for each drug. *Represents a significant difference from control, (P<0.05, Scheffé's test after two-way ANOVA).

Discussion

In the present study we wished to study the structure activity requirements of phorbol esters to enhance S-I serotonin and acetylcholine release in order to compare these with the structural requirements of phorbol esters for other PKC actions such as modulation of other neurotransmitters, tumour formation and skin irritation. In particular we compare our results extensively to our previous study where we examined the actions of phorbol esters on dopamine and noradrenaline release (Kotsonis & Majewski, 1996) in the same tissue as the present study using the same stimulation parameters.

Phorbol esters enhance action-potential-evoked serotonin release from a variety of brain regions: rabbit hippocampus (Feuerstein et al., 1987; Daschmann et al., 1988); rat brain parietal cortex slices (Wang & Friedman, 1987; 1989); rat brain synaptosomes (Nichols et al., 1987) and rat spinal cord (Gandhi & Jones, 1992) but most studies have used only a limited range of phorbol esters and therefore there is no systematic information of the optimal structures of phorbol esters to enhance serotonin release exists. A similar situation applies for acetylcholine release where a limited range of phorbol esters have been shown to enhance the depolarization-evoked release of acetylcholine in a variety of tissues: guinea-pig caudate (Tanaka et al., 1986); rat hippocampus (Versteeg & Florijn, 1987); rabbit hippocampus (Allgaier et al., 1988; Daschmann et al., 1988); rat cortical synaptosomes (Nichols et al., 1987); Torpedo synaptosomes (Guitart et al., 1990); guinea-pig ileum (Tanaka et al., 1984; Hashimoto et al., 1988); frog sartorius muscle (Caratsch et al., 1988); mouse phrenic nerve (Murphy & Smith, 1987); frog pectoris nerve (Haimann et al., 1987) and mouse atria (Dawson et al., 1996).

The phorbol esters used in the present study had markedly different effects on serotonin release ranging from large enhancements to no effect and this is discussed below in terms of structure.

In the present study, phorbol esters such as 4βPDB enhanced the S-I release of serotonin from rat cortex slices in a concentration-dependent manner. When the PKC was down-regulated by prior chronic exposure to 4βPDB (see Foucart et al., 1991; Schroeder et al., 1995), the facilitatory effects on serotonin release of acute 4βPDB was abolished. Furthermore, the phorbol esters 4αPDB and PA, which do not bind to or activate PKC (Kreibich & Hecker, 1970; Blumberg, 1980; Kikkawa et al., 1983), were without effect on serotonin release in accord with previous studies in other serotonergic systems (e.g. Wang & Friedman, 1987). Together, these results suggest that PKC is involved in the facilitatory effects of the phorbol esters on serotonin release.

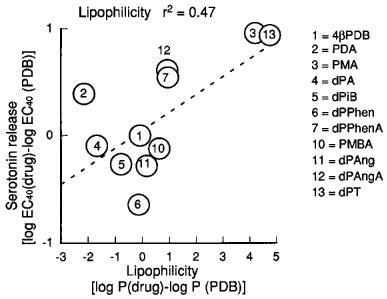

For phorbol derivatives with a common C13-acetate substituent, several structure-activity requirements to facilitate S-I serotonin release were observed. The structures are detailed in Table 1. The 12-deoxyphorbol, dPA, which differs from the inactive PA (see above) only in having an H instead of OH at C12, was a potent enhancer of serotonin release. If the C12 substituent is an extremely lipophilic group (e.g. myristate) as in PMA, then activity is greatly diminished compared to H (dPA) or acetate (PDA). For 12-deoxyphorbol derivatives which have a common H at the C12 position when the C13 ester substituent was made more lipophilic, the ability to enhance serotonin release was reduced (i.e. acetate (dPA) as well as angelate (dPAng), isobutyrate (dPiB), phenylacetate (dPPhen) >> tetradecanoate (dPT)). Taken together it would appear that the lipophilicity of either the C12 or C13 ester group selects against activity on transmitter release. The calculated lipophilicities are shown in Table 1. Those 12-deoxyphorbols with an acetate at C20 (dPAngA, dPPhenA) had decreased activity compared to the parent 12-deoxyphorbols without a 20-acetate (dPAng, dPPhen). Similarly, phorbol 12,13,20 phorbol triacetate had reduced effectiveness when compared with phorbol 12,13 diacetate (PDA). It has been suggested previously that lipophilic compounds require long contact times with the tissue to exert their effects but in the present study increasing the contact times up to 60 min did not produce an increased facilitatory effect of any phorbol esters tested (4βPDB, PDA, dPA, dPPhen, dPPhenA, PMA and dPT). Regression analysis showed a partial correlation with liphopilicity versus effects on serotonin release (r2=0.47), but some compounds departed markedly from the line of best fit suggesting that other factors were operative (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Correlation of the effects of phorbol esters to enhance fractional stimulation-induced (S-I) serotonin release with calculated lipophilicities of various phorbol esters. A log EC40 (log concentration of a drug to enhance serotonin release 40% above control) was calculated and the log EC40 of 4βPDB was subtracted and compared to the log P (drugs) minus log P of 4βPDB.

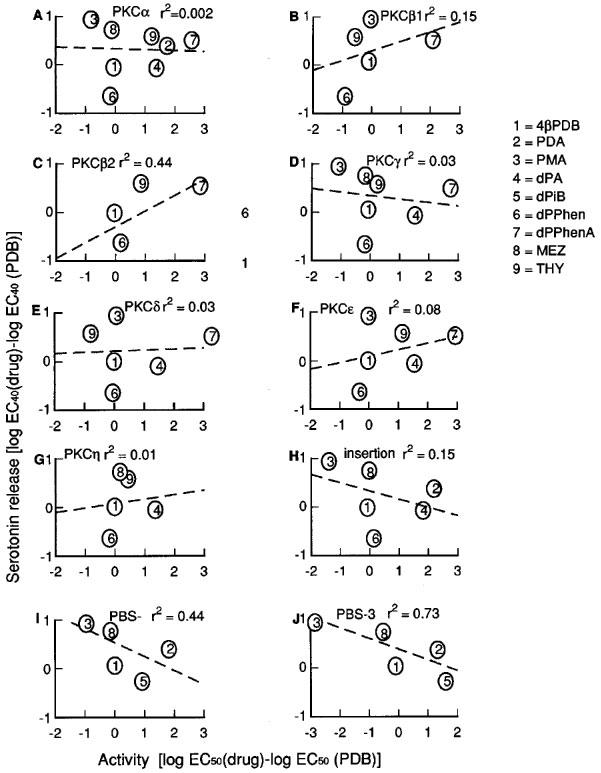

We compared the potency of the various drugs to elevate serotonin release with other key attributes for PKC activation. In this analysis we sought studies which had used 4βPDB and expressed either affinity or potencies of the other phorbol esters as a ratio of the 4βPDB effect to be able to relate all differences to a common denominator.

For PKCα for which most data points could be obtained, there was a poor correlation with effects of serotonin release with several compounds showing more than 1 log unit greater and lesser effects from the predicted potency if PKCα was involved (Figure 10A). Similar finding were observed for the other isozymes for which we obtained information which includes PKC β1, β2, γ, δ, ε and ζ (Figure 10). From the analysis, the short chain phorbols (dPA, PDA) always had increased potency compared to predicted and PMA always had decreased potency compared to predicted. The closest correlation was for PKCβ2 (Figure 10C), but caution should be used when interpreting the data because only a limited number of compounds could be compared and these tended not to be those at the extremes of transmitter release responses such as dPA, PMA or dPT. Where information was available, dPPhenA showed the greatest discrepancy being more potent on serotonin release than on any of the isozymes where it was tested by between 1.5–4 log units.

Figure 10.

Correlation of the effects of phorbol esters to enhance fractional stimulation-induced (S-I) serotonin release with reported affinities on different PKC isozymes. A log EC40 (log concentration of a drug to enhance serotonin release 40% above control) was calculated and the log EC40 of 4βPDB was subtracted and compared to the log EC50 (drugs) minus log EC50 of 4βPDB, for reported affinity values for each isozyme.

Another parameter which is reported to influence PKC activity is the ability of phorbol esters to insert PKC into membranes (Kazanietz et al., 1993). There were however marked differences in predicted potencies of the various phorbol esters on serotonin release and insertion ability with up to 2 log unit discrepancies in both directions (Figure 10H). Similarly the effects of phorbol esters on the two phorbol ester receptors described in mouse skin (Dunn & Blumberg, 1983) also showed little correlation with effects on serotonin release (Figure 10I, 10J).

At present it is not possible to be definitive about the variable effects of the various phorbol esters on transmitter release. Previously we suggested that the lipophilic compounds may have difficulty in penetrating the nerve terminal to reach the pools of PKC involved in transmitter release (Kotsonis & Majewski, 1996) and using [3H]-4βPDB as a radioligand in intact rat brain cortex synaptosomes, we found that PMA only slowly displaced binding compared to PDA and dPA but in α-toxin permeabilized synaptosomes the rates were similar for all three phorbol esters (Murphy et al., 1996).

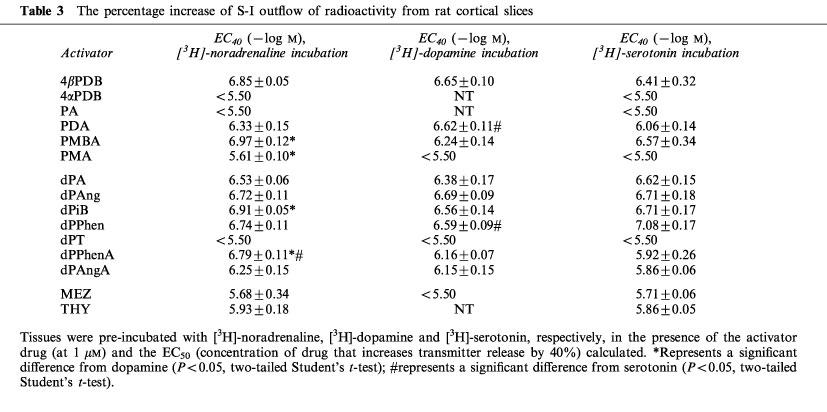

Whilst these kinetic differences may be a factor in determining the actions of the various phorbol esters on transmitter release, they fail to explain the observed differences in the abilities of the phorbol between transmitter types. We compared our data for serotonin release with that of Kotsonis & Majewski, 1996, who assessed the effects of the compounds on dopamine and noradrenaline release also in rat cortex, using the same stimulation parameters (Table 3). For the majority of the phorbol esters tested, there were no differences in their potencies across the three transmitter types (most of the phorbol esters tested had the equivalent potency (PDB, PMA, dP Ang, dPAngA)). However some phorbol esters showed significant differences between transmitter types. These included PDA (dopamine>serotonin); PMBA (noradrenaline >dopamine); dPPhenA (noradrenaline>dopamine>serotonin) with differences up to 0.9 log units for dPPhenA (noradrenaline compared to serotonin). These data suggest fundamental differences between neurotransmitter systems which need to be further investigated.

Table 3.

The percentage increase of S-I outflow of radioactivity from rat cortical slices

Finally we also investigated modulation of acetylcholine release and found that the effects of phorbol esters were very small (<25%; 4βPDB, PDA, dPA, dPAng, dPiB PMBA) and some had no effect at all (PMA, dPT, dPPhen) which compares with enhancements up to 150% for the same compounds for serotonin release. This suggests that the cholinergic transmitter release is less affected by PKC than other neurotransmitter types and since the release enhancement was so small no structure-activity analysis could be carried out. Other studies also indicate that PKC activation has a less marked effect on acetylcholine release. For example, in rabbit hippocampus the maximal effect on S-I noradrenaline release of phorbol dibutyrate was a 2.4 fold facilitation (Allgaier et al., 1987), whilst S-I acetylcholine release was only elevated by 0.7 fold in the same tissue (Allgaier et al., 1988). Similarly in mouse atria, S-I noradrenaline release was enhanced 1.6 fold by phorbol dibutyrate (Foucart et al., 1990) compared to 0.5 fold for S-I acetylcholine release (Dawson et al., 1996).

In conclusion the present study details the structure activity relationship for several phorbol esters in their ability to facilitate serotonin release from rat brain cortex. The activity profile cannot be explained by potency on any of the isoforms of PKC but rather indicates that lipophilic groups such as found in PMA and dPT decrease potency. Further, some compounds show selectivity between serotonin, dopamine and noradrenaline release which suggests that factors other than physicochemical parameters influence activity. The explanation may lie in subtle differences in how PKC modulates transmitter release in the various nerve types and in particular on the various substrates that are involved. These substrates have not as yet been worked out although candidates include ion channels, receptors, vesicular proteins and cytoskeletal elements (see Majewski & Iannazzo, 1998) and these may vary between neural systems. Finally, it should be noted that some non-tumour promoting phorbol esters (dPA) were excellent enhancers of serotonin release whilst some potent tumour promoters (PMA, dPT) were in fact quite poor suggesting a dissociation between transmitter release effects and tumour promotion. This has also been reported for dopamine and noradrenaline release (Kotsonis & Majewski, 1996).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Glaxo Wellcome Australia and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Abbreviations

- 4αPDB

4α-phorbol 12, 13-dibutyrate

- 4βPDB

4β-Phorbol 12, 13-dibutyrate

- DMSO

dimethyl sulphoxide

- dPA

12-deoxyphorbol 13-acetate

- dPAng

12-deoxyphorbol 13-angelate

- dPAngA

12-deoxyphorbol 13-angelate 20-acetate

- dPiB

12-deoxyphorbol 13-isobutyrate

- dPPhen

12-deoxyphorbol 13-phenylacetate

- dPPhenA

12-deoxyphorbol 13-phenylacetate 20-acetate

- dPT

12-deoxyphorbol 13-tetradecanoate

- FR

fractional stimulation induced outflow

- MEZ

mezerein

- PA

phorbol 13-acetate

- PDA

phorbol 12, 13-diacetate

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- PMBA

phorbol 12-methylaminobenzoate 13-acetate

- PSS

physiological salt solution

- PTA

phorbol 12, 13-triacetate

- S-I

stimulation-induced

- THY

thymeleatoxin

References

- ALLGAIER C., DASCHMANN B., HUANG H.Y., HERTTING G. Protein kinase C and presynaptic modulation of acetylcholine release in rabbit hippocampus. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;93:525–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb10307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALLGAIER C., HERTTING G., HUANG H.Y., JACKISCH R. Protein kinase C activation and α2-autoreceptor modulated release of noradrenaline. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987;92:161–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLUMBERG P.M. In vitro studies on the mode of action of the phorbol esters, potent tumor promoters. CRC Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1980;8:153–198. doi: 10.3109/10408448009037493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARATSCH C.G., SCHUMACHER S., GRASSI F., EUSEBI F. Influence of protein kinase C-stimulation by phorbol ester on neurotransmitter release at frog end-plates. Naunyn-Schmied. Arch. Pharmacol. 1988;337:9–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00169469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DASCHMANN B., ALLGAIER C., NAKOV R., HERTTING G. Staurosporine counteracts the phorbol-ester induced enhancement of neurotransmitter release in hippocampus. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. 1988;296:232–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWSON J.J., IANNAZZO L., MAJEWSKI H. Muscarinic autoinhibition of acetycholine release in mouse atria is not transduced through cyclic AMP or protein kinase C. J. Autonom. Pharmacol. 1996;16:79–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.1996.tb00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUNN J.A., BLUMBERG P.M. Specific binding of [20-3H]12-deoxyphorbol 13-isobutyrate to phorbol ester receptor subclasses in mouse skin particulate preparations. Cancer Res. 1983;43:4632–4637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FEUERSTIEN T.J., ALLGAIER C., HERTTING G. Possible involvement of protein kinase C (PKC) in the regulation of electrically evoked serotonin (5-HT) release from rabbit hippocampal slices. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1987;139:267–272. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90583-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOUCART S., MUSGRAVE I.F., MAJEWSKI H. Inhibition of noradrenaline release by neuropeptide Y does not involve protein kinase C in mouse atria. Neuropeptides. 1990;15:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(90)90011-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOUCART S., MUSGRAVE I.F., MAJEWSKI H. Long term treatment with phorbol esters suggests a permissive role for protein kinase C in the enhancement of noradrenaline release. Mol. Neuropharmacol. 1991;1:95–101. [Google Scholar]

- GANDHI V.C., JONES D.J. Protein kinase C modulates the release of [3H]5-hydroxytryptamine in the spinal cord of the rat: the role of L-type voltage dependent calcium channels. Neuropharmacology. 1992;31:1101–1109. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(92)90005-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUITART X., MARSAL J., SOLSNA C. Phorbol esters induce neurotransmitter release in cholinergic synaptosomes from Torpedo electric organ. J. Neurochem. 1990;55:468–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAIMANN C., MELDOLESI J., CECCARELLI B. 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate, enhances the evoked quanta release of acetylcholine at the frog neuromuscular junction. Plugers Arch. - Eur. J. Physiol. 1987;408:27–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00581836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASHIMOTO S., SHUNTOH H., TANIYAMA K., TANAKA C. Role of protein kinase C in the vesicular release of acetylcholine and norephinephrine from enteric neurons of the guinea pig small interstime. Jap. J. Pharmacol. 1988;48:377–385. doi: 10.1254/jjp.48.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERGENHAHN M., KUSUMOTO S., HECKER E. Diterpene esters from “Euphorbium” and their irritant and carcinogenic activity. Experientia. 1974;30:1438–1440. doi: 10.1007/BF01919683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAZANIETZ M.G., ARECES L.B., BAHADOR A., MISCHAT H., GOODNIGHT J., MUSHINSKI P., BLUMBERG P.M. Characterisation of ligand and substrate specificity for the calcium-dependent and calcium-independent protein kinase C enzymes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993;44:296–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAZANIETZ M.G., KRAUSZ K.W., BLUMBERG P.M. Differential irreversible insertion of protein kinase C into phospholipid vesicles by phorbol esters and related activators. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:20878–20886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIKKAWA U., TAKAI Y., TANAKA Y., MIYAKE R., NISHIZUKA Y. Protein kinase C as a possible receptor protein of tumor-promoting phorbol esters. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:11442–11445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOTSONIS P., MAJEWSKI H. The structural requirements for phorbol esters to ehance noradrenaline and dopamine release from rat brain cortex. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;119:115–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KREIBICH G., HECKER E. On the active principles of croton oil. X. Preparation of tritium labeled croton oil factor A1 and the other tritium labeled phorbol derivatives. Z. Krebsforsch. 1970;74:448–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAJEWSKI H., IANNAZZO L. Protein kinase C: a physiological mediator of enhanced transmitter output. Prog. Neurobiol. 1998;55:463–475. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURPHY R.L., SMITH M.E. Effects of diacylglycerol and phorbol ester on acetylcholine release and action at the neuromuscular junction in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1987;90:327–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb08962.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURPHY T.V.M., KOTSONIS P., MAJEWSKI H. Pharmacokinetic properties of phorbol esters are important in determining biological effects. Proc. Aust. Soc. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1996;3:41. [Google Scholar]

- NICHOLS R.A., HAYCOCK J.W., WANG J.K.T., GREENGARD P. Phorbol ester enhancement of neurotransmitter release from rat brain synaptosomes. J. Neurochem. 1987;48:615–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb04137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHIZUKA Y. Intracellular signalling by hydrolysis of phospholipids and activation of protein kinase C. Science. 1992;258:607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1411571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RYVES W.J., EVANS A.T., OLIVIER A.R., PARKER P.J., EVANS F.J. Activation of PKC-isotypes α, β1, γ, δ, and ε by phorbol esters of different biological activities. FEBS Lett. 1991;288:5–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80989-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHROEDER G.E., KOTSONIS P., MUSGRAVE I.F., MAJEWSKI H. Protein kinase C involvement in maintenance and modulation of noradrenaline release in the mouse brain cortex. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:2757–2763. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb17238.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STABEL S., PARKER P. Protein kinase C. Pharmacol Ther. 1991;51:71–95. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(91)90042-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZALLASI Z., KRSMANOVIC L., BLUMBERG P.M. Nonpromoting 12-deoxyphorbol 13 esters inhibit phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate induced tumor promotion in CD-1 mouse skin. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2507–2512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANAKA C., FUJIWARA H., FUJII Y. Acetylcholine release from guinea pig caudate slices evoked by phorbol ester and calcium. FEBS Letters. 1986;195:129–134. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANAKA C., TANIYAMA K., KUSUNOKI M. A phorbol ester and A23187 act synergistically to release acetylcholine from the guinea pig ileum. FEBS Letters. 1984;175:165–169. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VESTEEG D.H., FLORIJN W.J. Phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate enhances electrically stimulated neuromessenger release from rat dorsal hippocampal slices in vitro. Life Sciences. 1987;40:1237–1243. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90579-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG H.Y., FRIEDMAN E. Protein kinase C: regulation of serotonin release from rat brain cortical slices. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1987;141:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG H.Y., FRIEDMAN E. Lithium inhibition of protein kinase C activation-induced serotonin release. Psychopharmacol. 1989;99:213–218. doi: 10.1007/BF00442810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAYED S., SORG B., HECKER E. Structure activity relationship of polyfunctional diterpenes of the tigliane type, VI. Planta Med. 1984;34:65–69. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-969623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]