Abstract

Terodiline, an anticholinergic/antispasmodic drug effective in the treatment of urinary incontinence, is presently restricted due to adverse side effects on cardiac function. To characterize its effects on cardiac L-type Ca2+-channel current carried by Ca2+ (ICa,L) and Ba2+ (IBa,L), concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 100 μM were applied to whole-cell-configured guinea-pig ventricular myocytes.

Although sub-micromolar concentrations of terodiline had no effect on ICa,L at 0 mV, 100 μM drug reduced its amplitude to ca. 10% of pre-drug control. The estimated IC50 (15.2 μM in K+-dialysed cells, 12.2 μM in Cs+-dialysed cells; 0.1 Hz pulsing rate) is eight times higher than reported for ICa,L in bladder smooth muscle myocytes.

Terodiline affected ICa,L in a use-dependent manner; block increased when the pulsing rate was increased from 0.1 to 2–3 Hz, and when holding potential was lowered from −43 mV. The drug accelerated the decay of ICa,L at 0 mV in a concentration-dependent manner, and slowed the recovery of channels from inactivation.

Terodiline reduced peak IBa,L more effectively than peak ICa,L, and markedly accelerated the rate of inactivation of the current.

The results are discussed in terms of mechanisms of Ca2+ channel block and relation to the therapeutic and cardiotoxic effects of the drug.

Keywords: Terodiline; guinea-pig ventricular myocytes; L-type Ca2+ current (ICa,L); L-type Ba2+ current (IBa,L); use-dependent block; enhanced inactivation

Introduction

Terodiline is an anticholinergic agent (Husted et al., 1980) introduced in 1980 for the treatment of motor urge incontinence (Andersson & Ulmsten, 1980) and subsequently widely prescribed in Europe for a variety of urinary and other smooth muscle disorders (Andersson, 1984; Macfarlane & Tolley, 1984; Hallén et al, 1989; Langtry & McTavish, 1990). Terodiline antagonises Ca2+-dependent contraction in smooth muscle tissues (Husted et al., 1980; Østergaard et al., 1980; Larsson-Backström et al., 1985), and this property is a factor in the effectiveness of the drug in urinary incontinence (Andersson, 1984; Langtry & McTavish, 1990). The antagonism probably reflects a block of L-type channels, and Kura et al. (1992) has reported that the drug inhibits guinea-pig bladder L-type Ca2+ current (ICa,L) with an IC50 of 1.7 μM.

Terodiline has adverse effects that include sinus slowing and conduction disturbances in the atrioventricular node (Connolly et al., 1991; Davies et al, 1991), as well as QT lengthening and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (McLeod et al., 1991; Connolly et al., 1991; Stewart et al., 1992; Thomas et al., 1995). This cardiotoxic profile led to a worldwide withdrawal of terodiline in 1991. However, the drug is still authorized for clinical investigation, and derivatives are either under development for possible therapeutic use (e.g., Taniguchi et al., 1994; Take et al., 1996) or have already reached the market (Abrams et al., 1998).

There have been relatively few studies on the effects of terodiline on isolated cardiac preparations, but they suggest that the drug has a much weaker action on cardiac ICa,L than on bladder myocyte ICa,L. For example, Larsson-Backström et al. (1985) found that terodiline inhibited rat papillary muscle contraction with an IC50 of 18 μM, and Hayashi et al. (1997) reported that the drug inhibited guinea-pig ventricular ICa,L with an IC50 of 34 μM. We have recorded ICa,L in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes, and used concentrations of terodiline between 0.1 and 100 μM (therapeutic plasma concentration 1–1.8 μM: Connolly et al., 1991) to evaluate concentration-, frequency- and voltage-dependent actions of the drug.

Methods

Ventricular myocytes

Guinea-pigs weighing 250–350 g were killed by cervical dislocation in accord with local and national regulations, and single ventricular myocytes were enzymatically isolated as described previously (Ogura et al., 1995). The excised hearts were mounted on a Langendorff column, and retrogradely perfused (37°C) through the aorta with Ca2+-free Tyrode's solution that contained collagenase (0.08–0.12 mg ml−1: Yakult Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan) for 10–15 min. The cells were dispersed and stored at ≈22°C in a high-K+, low-Na+ solution supplemented with 50 mM glutamic acid and 20 mM taurine. A few drops of the cell suspension were placed in a 0.3-ml perfusion chamber mounted on an inverted microscope stage. After the cells had settled to the bottom, the chamber was perfused (≈ 2 ml min−1) with Tyrode's solution. The Tyrode's solution contained (in mM) NaCl 140, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1, glucose 10, and N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulphonic acid (HEPES) 5 (pH 7.4 with NaOH). In some experiments, the Tyrode's solution was exchanged for K+-free Tyrode's or for K+-free Ca2+-free solution that contained 1.5 mM Ba2+.

Whole-cell membrane currents were recorded using an EPC-7 amplifier (List Electronic, Darmstadt, Germany). Recording pipettes were fabricated from thick-walled borosilicate glass capillaries (H15/10/137, Jencons Scientific Ltd., Bedfordshire, U.K.) and filled with (i) K+ solution that contained (in mM) KCl 40, potassium aspartate 106, Mg-ATP 1, K2-ATP 4, ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) 5 and HEPES 5 (pH 7.2 with KOH), or (ii) K+-free solution (K+ replaced by Cs+). The pipettes had resistances of 1.5–2.5 MΩ when filled with pipette solution, and liquid junction potentials between external and pipette-filling solution were nulled prior to patch formation. Series resistance ranged between 3 and 7 MΩ and was compensated by 60–80%. Membrane current signals were filtered at 3 kHz, and digitized with an A/D converter (Digidata 1200A, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.) and pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments) at a sampling rate of 8 kHz prior to analysis.

The myocytes were generally held at −80 or ca. −40 mV, and pulsed to 0 mV for 200 ms at 0.1–0.2 Hz to elicit ICa,L; when held at −80 mV, the pulses to 0 mV were preceded by 100-ms depolarizations to −40 mV to inactivate Na+ current and any T-type Ca2+ current. Experiments were conducted at 36±0.5°C.

Drugs

Terodiline (Sepracor Inc., Marlborough, MA, U.S.A.) was freshly dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.) immediately prior to use. The highest final concentration of DMSO in the superfusate was 0.01% v v−1 (100 μM drug), a concentration that has no significant effect on electrical and contractile activity in guinea-pig papillary muscle, or on membrane currents in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes (Ogura et al., 1995). The vehicle was included in control solutions for the experiments depicted in Figures 4, 5, 6.

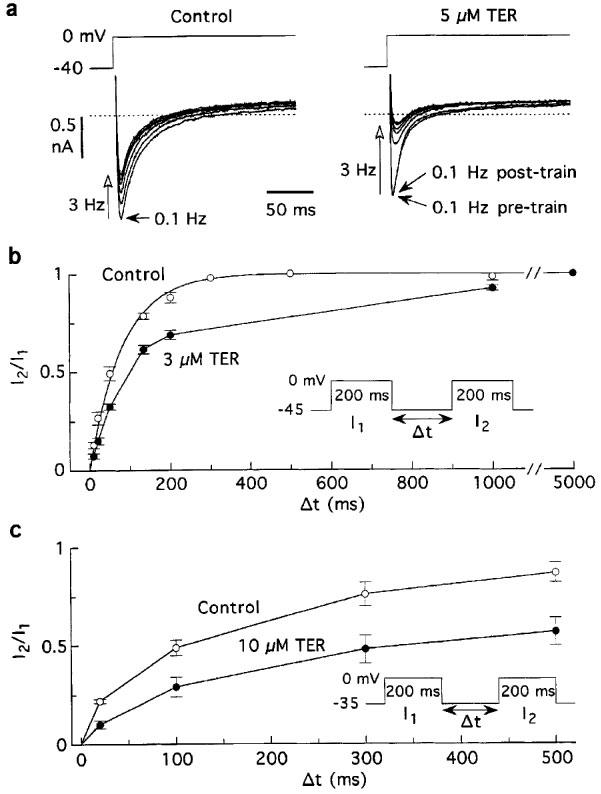

Figure 4.

Terodiline enhances frequency-dependent reduction of ICa,L and slows recovery of the current from inactivation. Myocytes were bathed and dialysed with K+ solutions, and pulsed at a basic rate of 0.1 Hz. (a) Records illustrating the reduction of ICa,L induced by 3-Hz trains of 25 pulses before and 6 min after addition of 5 μM terodiline. (b) Time courses of recovery of ICa,L from 200-ms inactivating pulses before and ca. 5 min after addition of 3 μM terodiline. The exponential fitting the control data (n=10 myocytes) has τ=82 ms. A point-to-point line is used to connect the terodiline data since they are poorly described by a single exponential (c) Recovery from inactivation in four myocytes held at −35 mV and treated with 10 μM terodiline.

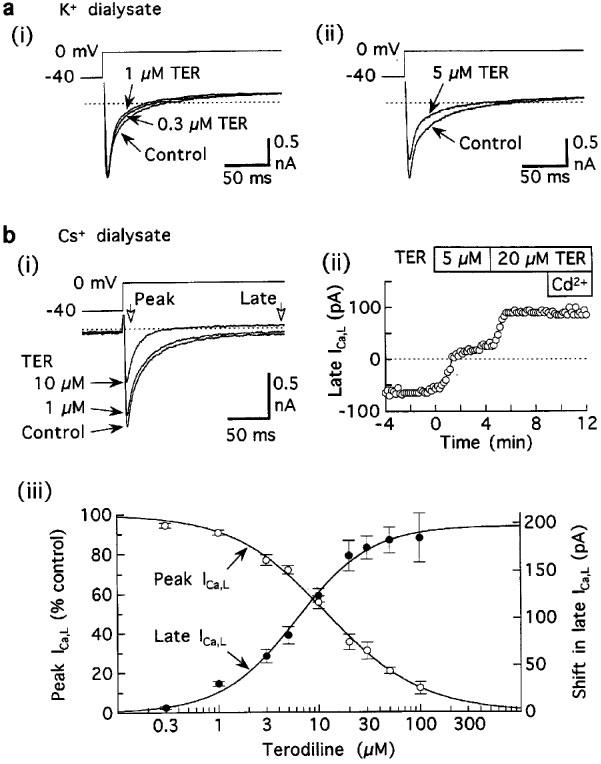

Figure 5.

Acceleration of inactivation of ICa,L by terodiline. (a) Records from myocytes superfused and dialysed with K+ solutions, and pulsed at 0.1 Hz. (i) Acceleration in the absence of significant reduction of ICa,L amplitude in a myocyte treated with 0.3 μM terodiline for 5 min and 1 μM terodiline for a further 5 min. (ii) Acceleration in a myocyte treated with 5 μM drug for 3 min. Relatively large outward currents at holding potential −40 mV have been omitted for presentation purposes. (b) Results from experiments in which K+-free solutions were used to minimize K+ currents. (i) Records from a representative myocyte treated for 6 min (1 μM) and then 4 min (10 μM). (ii) Time course of shifts in late ICa,L. (iii) Concentration-response relationships for Ca2+-sensitive peak ICa,L (open circles) and shift in late ICa,L (closed circles). Pulsing rate 0.1 Hz. Number of myocytes: 4–14 at each concentration.

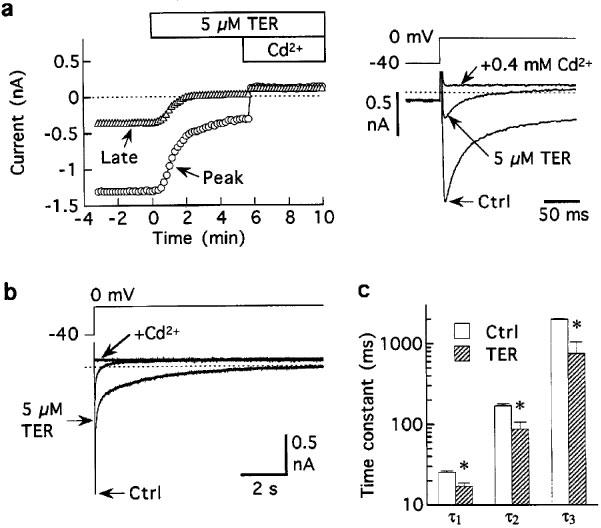

Figure 6.

Inhibition of Ba2+-carried current by 5 μM terodiline. (a) Representative results. Note that inhibition of late IBa,L was larger than inhibition of peak IBa,L. Pulsing rate 0.1 Hz. (b) Superimposed records showing the first 10 s of currents elicited by 20-s depolarizations before, 6 min after addition of 5 μM terodiline, and 3 min after subsequent addition of 0.4 mM Ca2+. (c) Time constants obtained from multiexponential analysis of Cd2+-sensitive IBa,L recorded from five myocytes investigated as in (b) *P<0.05.

Statistics

Results are expressed as means±s.e.mean, and comparisons were made using Student's t-test. Differences were considered significant when P<0.05.

Results

Concentration-dependent inhibition of ICa,L

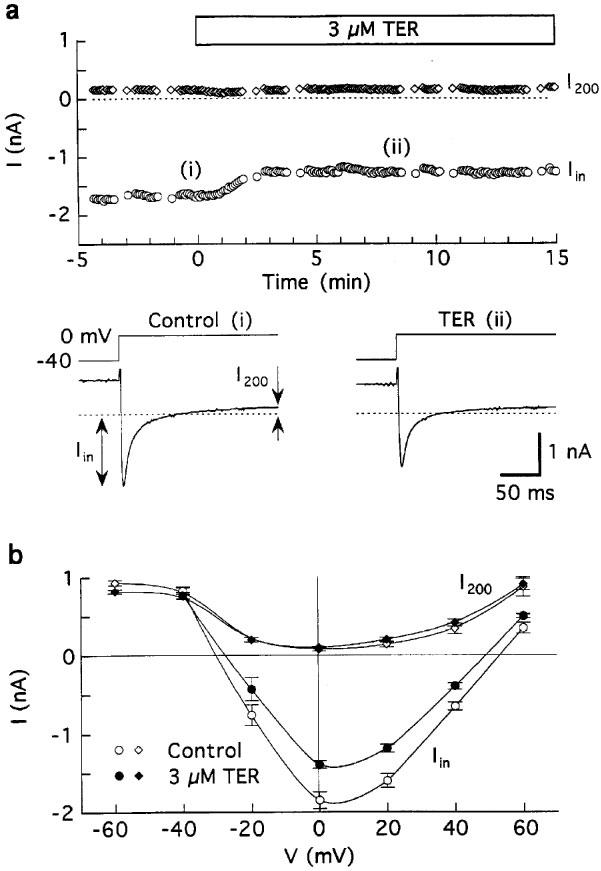

Figure 1 depicts the results obtained from five myocytes bathed and dialysed with K+ solutions, depolarized with 200-ms pulses applied at 0.2 Hz, and treated with 3 μM terodiline for 9–12 min. The drug reduced estimated ICa,L (peak inward current (Iin)) at 0 mV by 26±4% (P<0.005) (Figure 1b), with little effect on the end-of-pulse outward current (I200) level. The inhibition was independent of test potential between −20 and +20 mV; at more positive potentials, Iin curves converged on I200 curves in a manner suggesting little effect on the reversal potential of ICa,L.

Figure 1.

Effects of 3 μM terodiline on membrane currents in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes superfused with Tyrode's solution and dialysed with K+ pipette solution. The myocytes were depolarised for 100 ms from −80 to −40 mV, and pulsed to 0 mV for 200 ms at 0.2 Hz except for determinations of I–V relationships. (a) Data from a representative experiment. Top: time course of changes in peak inward (Iin) and end-of-pulse current (I200) amplitudes at 0 mV, measured with respect to zero current. Bottom: records obtained at the times indicated in the time plot. (b) Average of I–V relationships obtained before (control) and 9–12 min after addition of 3 μM drug; n=five myocytes.

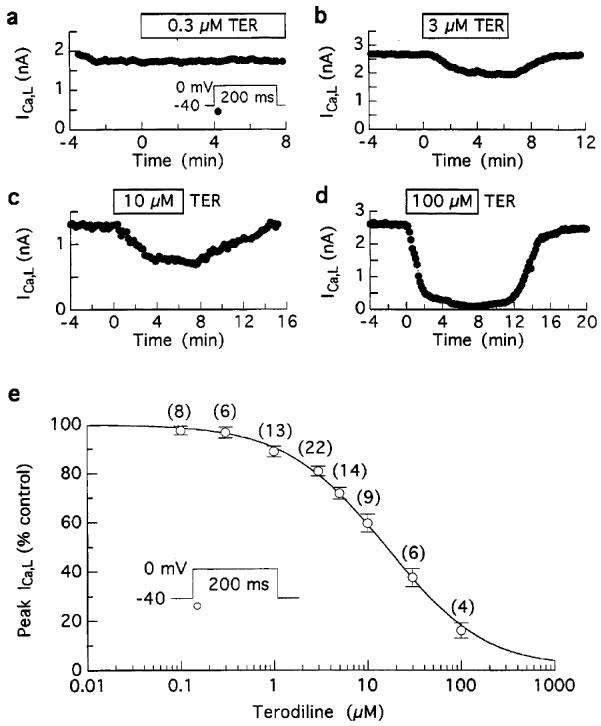

The time plots in Figure 2a–d illustrate that submicromolar terodiline had little effect on ICa,L whereas 3, 10 and 100 μM drug reversibly inhibited the current by 25, 40 and 95%, respectively. The results obtained from these and similar experiments are well described by a Hill equation, ICa,L (% control)=100/{1+([TER]/IC50)nH}, in which the IC50 is 15.2 μM, and the Hill coefficient is 0.84 (Figure 2e).

Figure 2.

Concentration-dependent inhibition of ICa,L amplitude by terodiline. ICa,L at 0 mV was elicited by 200 ms pulses from −40 mV at 0.1 Hz in myocytes bathed and dialysed with K+ solutions. (a-d) Results from representative experiments. (e) Concentration-response relationship. Most (>85%) of the myocytes were treated with a single concentration for 6–12 min, and ICa,L amplitude measured as Iin was expressed as a percentage of pre-drug control. The data are described by a Hill equation, ICa,L (% control)=100/{1+([TER]/IC50)nH}, with IC50=15.2 μM, and Hill coefficient nH=0.84. Number of myocytes in parentheses.

Dependence of inhibition on holding potential and stimulation rate

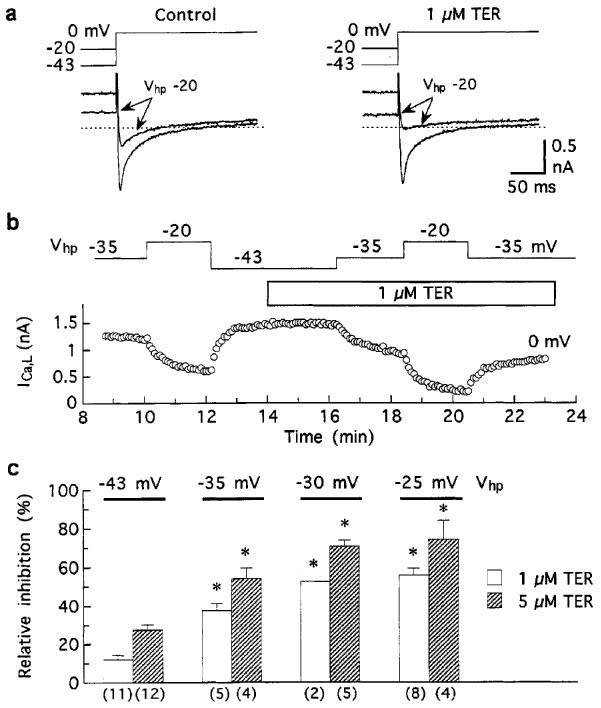

To investigate whether inhibition of ICa,L by terodiline is sensitive to depolarization, the holding potential in myocytes pulsed to 0 mV was changed from ca. −43 mV to more positive potentials for short (2- to 3-min) test periods. Although lowering of the holding potential reduced control ICa,L (as expected from a voltage-dependent reduction in Ca2+ channel availability), the effect was much larger after addition of the drug (Figure 3a,b). In trials on 23 myocytes treated with 1 or 5 μM terodiline, the degree of drug-induced inhibition was assessed at holding potentials of −43, −35, −30 and −25 mV. Each reduction in holding potential accentuated inhibition by the drug (Figure 3c). For example, relative inhibition by 1 μM terodiline was 12±2% (n=11 observations) at −43 mV holding potential, 33±5% (n=5) at −35 mV, and 56±4% (n=8) at −25 mV.

Figure 3.

Effect of holding potential on the inhibition of ICa,L by terodiline. Myocytes bathed and dialysed with K+ solutions were held at different potentials and pulsed to 0 mV at 0.2 Hz. (a) Records showing the steady-state effects of changing the holding potential (Vhp) from −43 to −20 mV for 3 min before (left), and 6 min after addition of 1 μM drug. (b) Time course of changes in ICa,L amplitude induced by changes in holding potential before and during exposure to 1 μM drug. To minimize the effects of the shift in late current on ICa,L measurements, the amplitude was measured as I200–Iin (see Figure 1). (c) Summary of data obtained from myocytes treated with 1 or 5 μM drug. Inhibition at each holding potential is expressed relative to pre-drug current elicited at 0 mV from that holding potential. Numbers of myocytes in parentheses. *P<0.001 versus relative inhibition at −43 mV.

To investigate whether inhibition is sensitive to stimulation rate, myocytes were regularly pulsed for 200 ms from −40 to 0 mV at 0.1 Hz, and periodically tested with trains of 25 pulses at 3 Hz. Since the 133-ms period between pulses in a train was too short for full recovery of ICa,L from inactivation, these trains provoked significant reductions in ICa,L under pre-drug control conditions (c.f., Boyett et al., 1994; Asai et al., 1996) (Figure 4a). Relative to ICa,L amplitude at 0.1 Hz just prior to a 3-Hz train, the reductions caused by the trains were more severe in the presence of the drug (Figure 4a). In seven myocytes, ICa,L at 3 Hz declined to 32±5% of its 0.1-Hz amplitude after treatment with 5 μM terodiline, compared to pretreatment decline to 68±5% (P<0.001). Smaller effects were observed with lower terodiline and lower test frequency. For example, an increase from 0.1 to 2 Hz in the presence of 1 μM terodiline reduced ICa,L to 74±5% (n=4) versus pretreatment 87±5% (P<0.01).

A plausible explanation for the frequency-dependent component of terodiline action is that the drug slows the recovery of ICa,L from inactivation. To determine whether this is the case, 200-ms double pulses to 0 mV were applied to ten myocytes held at −45 mV, with recovery time (separation between the two pulses) ranging from 10 ms to 5000 ms. The time course of recovery prior to drug treatment was adequately described by an exponential with time constant 82 ms, whereas that determined after ca. 5 min treatment with 3 μM terodiline was slower and no longer monoexponential (Figure 4b). When the time course of recovery was characterised in terms of halftime, the drug slowed the process by a factor of 1.9. Four other myocytes held at −35 mV were tested with recovery intervals of 20, 100, 300 and 500 ms. The results in Figure 4c indicate that 10 μM terodiline slowed the halftime of recovery from 105 to 340 ms.

Acceleration of current decay

Terodiline accelerated the decay of Ca2+ channel currents observed during 200-ms depolarisations to 0 mV and this effect was more pronounced at higher drug concentrations (Figure 5a). Using I200–Iin as an estimate of the time course of ICa,L in myocytes investigated under standard conditions (Tyrode's solution; K+ dialysate) (Figure 5a), the time to half-decay declined from control 10.2±0.7 ms to 8.0±0.7 ms (n=8) (P<0.005) after exposure to 5 μM terodiline.

To investigate the acceleratory effects of terodiline in greater detail, K+-free internal and external solutions were used to minimise K+ currents, and 0.4 mM Cd2+ was used to establish a background–current reference level for measurement of Ca2+-channel currents carried by either Ca2+ or Ba2+. In the first series of experiments, ICa,L elicited by 200-ms pulses to 0 mV was recorded before and during exposure to 0.3–100 μM terodiline. The representative results in Figure 5b indicate that the drug inhibited both peak ICa,L and late (end-of pulse) ICa,L. The IC50 for inhibition of peak ICa,L was 12 μM, and the IC50 for inhibition of late ICa,L was 6 μM (Figure 5c). This discrepancy in IC50 values suggests that post-peak-ICa,L decayed more rapidly after addition of terodiline.

For the experiments on Ba2+-carried current (IBa,L), external Ca2+ was replaced by 1.5 mM Ba2+, and myocytes were pulsed at 0.1 Hz with 200-ms steps to 0 mV. The results from a representative myocyte indicate that 5 μM terodiline had a pronounced inhibitory effect on peak IBa,L, and an even stronger one on late IBa,L (Figure 6a). In eleven myocytes, 5 μM drug reduced peak Cd2+-sensitive IBa,L to 43±2% control, and reduced late Cd2+-sensitive IBa,L to 24±1% control, a difference (P<0.001) that is best explained as an acceleration of inactivation. To establish the extent of the acceleration, five myocytes otherwise pulsed to 0 mV for 200 ms at 0.1 Hz, were probed with single 20-s depolarizations to 0 mV on three occasions: before addition of 5 μM terodiline, after steady-state inhibition, and after subsequent nulling of the current with 0.4 mM Cd2+. Although control IBa,L failed to inactivate completely during 20-s depolarizations prior to addition of terodiline, it decayed to the background current level within 5 s when the drug was present (Figure 6b). As previously reported by Boyett et al. (1994), the time course of inactivation of Cd2+-sensitive IBa,L was best-described by up to four exponential functions. However, the salient features are captured by the first three exponentials (time constants 25±1, 171±9, 1982±38 ms), each of which was significantly (P<0.05) shortened by the drug (time constants 17±2, 87±19, 749±290 ms) (Figure 6c).

Discussion

Concentration-dependent inhibition of peak ICa,L

Terodiline induced a concentration-dependent reduction in the amplitude of ICa,L in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes pulsed to 0 mV at 0.1–0.2 Hz. Data from myocytes bathed and dialysed with K+ solutions were best described by a Hill equation with IC50 of 15.2 μM, whereas data on Cd2+-sensitive peak ICa,L from myocytes investigated under K+-free conditions were best described with an IC50 of 12.2 μM. The estimate determined under K+ conditions is considerably lower than the K0.5 of 33.5 μM reported by Hayashi et al. (1997) in a study on guinea-pig ventricular myocytes under similar (K+, temperature, pulsing rate) experimental conditions. A difference in methodology is that they measured the effects of short (≈3 min) cumulative exposures to six terodiline concentrations between 1 and 300 μM, and it is possible that this skewed the results to some degree.

The IC50 determined for ventricular ICa,L is about eight times larger than the 1.7-μM value reported by Kura et al. (1992) for inhibition of ICa,L in guinea-pig bladder smooth muscle myocytes. One difference in the behaviour of ICa,L in the two studies is that pre-drug ICa,L in the bladder myocytes was strongly affected by relatively low pulsing frequencies; a ca. 40% reduction in amplitude occurred during short 0.2-Hz trains of depolarisations to 0 mV, presumably because the recovery of ICa,L from inactivation was slow at the low (22°C) experimental temperature employed in the study. It may be that measurement difficulties arising from calculations of terodiline inhibition based on relative control- and terodiline-induced use-dependent inhibition contributed to over-estimates of terodiline action at the two concentrations (1 and 10 μM) whose effects were fitted with a Michaelis-Menten equation to determine the IC50. However, this is speculation, and the difference in IC50 values may instead reflect a significant difference in the sensitivity of ICa,L to terodiline in the two cell types.

Inhibition of peak IBa,L

IBa,L was more sensitive than ICa,L to inhibition by terodiline. Peak IBa,L was reduced to 43±2% (n=11) by 5 μM drug, whereas peak ICa,L in similar (Cs+-dialysed) myocytes was only reduced to 72±2% (n=7) by 5 μM drug (P<0.001 versus IBa,L), and to 56±3% (n=13) by 10 μM drug (P<0.01 versus IBa,L). Based on the peak ICa,L data presented in Figure 5c, terodiline was about 2.7 times more inhibitory on peak IBa,L than ICa,L. In a recent study on fendiline, a drug with structural similarities to terodiline, Nawrath et al. (1998) found that the IC50 was 8 μM for IBa,L and 13 μM for ICa,L. They suggested that the more potent inhibition of IBa,L was related to the enhanced openness of Ca2+ channels when Ba2+ is the charge-carrier, and a similar reason could be advanced in regard to terodiline action.

Use-dependent inhibition

In their study on bladder smooth muscle myocytes, Kura et al. (1992) observed that inhibition of ICa,L by 10 μM terodiline developed more quickly when myocytes were pulsed at 1 Hz rather than 0.1 Hz. The present results indicate that terodiline-induced block of ICa,L in guinea-pig ventricular cells is enhanced by increases in pulsing frequency. They also establish that inhibition by terodiline is favoured by lower holding potentials, and that recovery of ICa,L from inactivation is slowed in drug-treated myocytes, two properties that are associated with a number of organic compounds that block L-type Ca2+ channels (McDonald et al., 1994).

The decay of ICa,L at 0 mV was accelerated when myocytes were exposed to terodiline. The acceleration was evident in myocytes treated with low micromolar concentrations that had little effect on ICa,L amplitude, and was more pronounced in myocytes treated with higher concentrations of the drug. As a consequence, late ICa,L flowing at 0 mV declined with increasing drug concentration. Terodiline also accelerated the decay of IBa,L, a long-lasting current that inactivates with a multi-exponential time course (Boyett et al., 1994), and analysis of this action indicates that the drug shortens the time constant of the three major phases of the inactivation.

There is evidence that some organic Ca2+ channel blockers accelerate the decay of Ca2+ channel currents, and that others do not (McDonald et al., 1994). Nawrath et al. (1998) have recently reported that fendiline illustrates this diversity: 10 μM fendiline accelerated the decay of IBa,L in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes, whereas 10 μM verapamil did not. They postulated that verapamil does not affect the time course of current decay during a depolarization because it primarily binds to inactivated channels. However, fendiline is postulated to block open channels, and the resultant time-dependent removal of channels from the conducting pool is observed as a speeding up of the decay of the current. To estimate the time course of this block, they analysed the ‘fractional block' of IBa,L elicited by 300-ms pulses to +10 mV, and concluded that block occurred along a monoexponential time course with τ≈ 100 ms.

Our results with terodiline are not as tidy as those with fendiline because a similar type of fractional block analysis failed to identify a monoexponential process. One could argue that the requirement for a multiexponential description for the fractional block reflects differing rates of binding to the multiple open states of Ca2+ channels conducting Ba2+. Alternatively, acceleration of the multiple phases of decay of IBa,L may reflect actual acceleration of multiple inactivation process (Figure 6). The present results do not warrant any additional speculation, especially since the physical meaning of the multiexponential decay of long-lasting IBa,L is obscure (c.f., Boyett et al., 1994).

Relation to clinical observations

Use-dependent block of L-type Ca2+ channels may well have been an important factor in the treatment of unstable bladder with terodiline, not only because the bladder muscle cells-themselves are in a hyperactive state (Brading & Turner, 1994), but also because activity-dependent facilitation of prejunctional L-type channels appears to be of clinical significance in unstable bladder conditions (Somogyi et al., 1997). Since M1 muscarinic receptors have an important role in this facilitation (Somogyi et al., 1997), and M1 antagonism by terodiline is as potent as that of the classical M1 antagonist pirenzipine (Noronha-Blob et al., 1991; Gallo et al., 1993), there is scope for a synergistic stabilizing action of the drug on bladder function.

The primary cardiotoxic effects of terodiline include prolongation of the QT interval and ventricular tachyarrhythmia. Inhibition of ICa,L is unlikely to be the cause of these developments, and may even help prevent their occurrence. However, inhibition of the current may well be a contributory factor in the slowing of heart rate and nodal conduction observed in patients with high plasma concentrations of terodiline (up to 9.6 μM: Connolly et al., 1991; Stewart et al., 1992).

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Gina Dickie for laboratory assistance and Mr Brian Hoyt for technical support. L.M. Shuba held a scholarship from the Dalhousie Medical Research Foundation. The study was funded by Sepracor Inc. and the Medical Research Council of Canada.

Abbreviations

- (ICa,L)

L-type Ca2+ current

- (IBa,L)

L-type Ba2+current

References

- ABRAMS P., FREEMAN R., ANDERSTRÖM C., MATTIASSON A. Tolterodine, a new antimuscarinic agent: as effective but better tolerated than oxybutynin in patients with an overacting bladder. Br. J. Urol. 1998;81:801–810. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDERSSON K.-E., ULMSTEN U. Drug treatment of the overactive detrusor. Acta Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1980;46 Suppl. I:7–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1980.tb03242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDERSSON K.E. Clinical pharmacology of terodiline. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. 1984;87:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASAI T., PELZER S., MCDONALD T.F. Cyclic AMP-independent inhibition of cardiac calcium current by forskolin. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;50:1262–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOYETT M.R., HONJO H., HARRISON S.M., ZANG W-J., KIRBY M.S. Ultra-slow voltage-dependent inactivation of the calcium current in guinea-pig and ferret ventricular myocytes. Pflügers Arch. 1994;428:39–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00374750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADING H.F., TURNER W.H. The unstable bladder: towards a common mechanism. Br. J. Urol. 1994;73:3–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1994.tb07447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONNOLLY M.J., ASTRIDGE P.S., WHITE E.G., MORLEY C.A., COWAN J.C. Torsades de pointes ventricular tachycardia and terodiline. Lancet. 1991;338:344–345. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIES S.W., BRECKER S.J., STEVENSON R.N. Terodiline for treating detrusor instability in elderly people. Br. Med. J. 1991;302:1276. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6787.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALLO M.P., ALLOATTI G., EVA C., OBERTO A., LEVI R.C. M1 muscarinic receptors increase calcium current and phosphoinositide turnover in guinea-pig ventricular cardiocytes. J. Physiol. 1993;471:41–60. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALLÉN B., BOGENTOFT S., SANDQUIST S., STRÖMBERG S., SETTERBERG G., RYD-KJELLÉN E. Tolerability and steady-state pharmacokinetics of terodiline and its main metabolities in elderly patients with urinary incontinence. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1989;36:487–493. doi: 10.1007/BF00558074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYASHI S., NATSUKAWA T., SUMA C., UKAI Y., YOSHIKUNI Y., KIMURA K. Cardiac electrophysiological actions of NS-21 and its active metabolite, RCC-36, compared with terodiline. Pflügers Arch. 1997;355:651–658. doi: 10.1007/pl00004997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUSTED S., ANDERSSON K.-E., SOMMER L., ØSTERGAARD J.R. Anticholinergic and calcium antagonistic effects of terodiline in rabbit urinary bladder. Acta Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1980;46 Suppl. I:20–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1980.tb03244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KURA H., YOSHINO M., YABU H. Blocking action of terodiline on calcium channels in single smooth muscle cells of the guinea pig urinary bladder. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;261:724–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANGTRY H.D., MCTAVISH D. Terodiline. A review of its pharmacological properties, and therapeutic use in the treatment of urinary incontinence. Drugs. 1990;40:748–761. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199040050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LARSSON-BACKSTRÖM C., ARRHENIUS E., SAGGE K. Comparison of the calcium-antagonistic effects of terodiline, nifedipine and verapamil. Acta Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1985;57:8–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1985.tb00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACFARLANE J.R., TOLLEY D.A. The effect of terodiline on patients with detrusor instability. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. 1984;87:51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCDONALD T.F., PELZER S., TRAUTWEIN W., PELZER D.J. Regulation and modulation of calcium channels in cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscle cells. Physiol. Rev. 1994;74:365–507. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLEOD A.A., THOROGOOD S., BARNETT S. Torsades de pointes complicating treatment with terodiline. Br. Med. J. 1991;302:1469. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6790.1469-c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAWRATH H., KLEIN G., RUPP J., WEGENER J.W., SHAINBERG A. Open state block by fendiline of L-type Ca2+ channels in ventricular myocytes from rat heart. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;285:546–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORONHA-BLOB L., PROSSER J.C., STURM B.L., LOWE V.C., ENNA S.J. (±)-Terodiline: an M1-selective muscarinic receptor antagonist. In vivo effects at muscarinic receptors mediating urinary bladder contraction, mydriasis and salivary secretion. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991;201:135–142. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90336-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OGURA T., SHUBA L.M., MCDONALD T.F. Action potentials, ionic currents and cell water in guinea pig ventricular preparations exposed to dimethyl sulfoxide. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;273:1273–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ØSTERGAARD J.R., ØSTERGAARD K., ANDERSON K.-E., SOMMER L. Calcium antagonistic effects of terodiline in rabbit aorta and human uterus. Acta Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1980;46 Suppl. I:12–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1980.tb03243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOMOGYI G.T., ZERNOVA G.V., TANOWITZ M., GROAT W.C. Role of L- and N-type Ca2+ channels in muscarinic receptor-mediated facilitation of Ach and noradrenaline release in the rat urinary bladder. J. Physiol. 1997;499:645–654. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEWART D.A., TAYLOR J., GOSH S., MACPHEE G.J.A., ABDULLAH I., MCLENACHAN J.M., STOTT D.J. Terodiline causes polymorphic ventricular tachycardia due to reduced heart rate and prolongation of QT interval. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1992;42:577–580. doi: 10.1007/BF00265918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKE K., OKUMURA K., TSUBAKI K., TANIGUCHI K., TERAI T., SHIOKAWA Y. Agents for the treatment of overactive detrusor. V. Synthesis and inhibitory activity on detrusor contraction of N-tert-butyl-4,4-diphenyl-2-cyclopentenylamine. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1996;44:1858–1864. doi: 10.1248/cpb.44.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANIGUCHI K., TSUBAKI K., TAKE K., OKUMURA K., TERAI T., SHIOKAWA Y. Agents for the treatment of overactive detrusor. VII. Synthesis and pharmacological properties of 2,3- and 3,4-diphenylcyclopentylamines, 2,3-diphenyl-2-cyclopentenylamines, and related compounds. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1994;42:896–902. doi: 10.1248/cpb.42.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMAS S.H.L., HIGHAM P.D., HARTIGAN-GO K., KAMALI F., WOOD P., CAMPBELL R.W.F., FORD G.A. Concentration dependent cardiotoxicity of terodiline in patients treated for urinary incontinence. Br. Heart J. 1995;74:53–56. doi: 10.1136/hrt.74.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]