Abstract

Prostaglandin (PG) E2 is formed from PGH2 by a series of PGE synthase (PGES) enzymes. Microsomal PGES-1−/− (mPGES-1−/−) mice were crossed into low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout (LDLR−/−) mice to generate mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−s. Urinary 11α-hydroxy-9, 15-dioxo-2,3,4,5-tetranor-prostane-1,20-dioic acid (PGE-M) was depressed by mPGES-1 deletion. Vascular mPGES-1 was augmented during atherogenesis in LDLR−/−s. Deletion of mPGES-1 reduced plaque burden in fat-fed LDLR−/−s but did not alter blood pressure. mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/− plaques were enriched with fibrillar collagens relative to LDLR−/−, which also contained small and intermediate-sized collagens. Macrophage foam cells were depleted in mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/− lesions, whereas the total areas rich in vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) and matrix were unaltered. mPGES-1 deletion augmented expression of both prostacyclin (PGI2) and thromboxane (Tx) synthases in endothelial cells, and VSMCs expressing PGI synthase were enriched in mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/− lesions. Stimulation of mPGES-1−/− VSMC and macrophages with bacterial LPS increased PGI2 and thromboxane A2 to varied extents. Urinary PGE-M was depressed, whereas urinary 2,3-dinor 6-keto PGF1α, but not 2,3-dinor-TxB2, was increased in mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−s. mPGES-1-derived PGE2 accelerates atherogenesis in LDLR−/− mice. Disruption of this enzyme retards atherogenesis, without an attendant impact on blood pressure. This may reflect, in part, rediversion of accumulated PGH2 to augment formation of PGI2. Inhibitors of mPGES-1 may be less likely than those selective for cyclooxygenase 2 to result in cardiovascular complications because of a divergent impact on the biosynthesis of PGI2.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, cyclooxygenase, macrophage, vascular smooth muscle cell

Recent placebo-controlled trials have revealed that nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) selective for inhibition of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) confer a small but absolute risk of myocardial infarction and stroke (1–5). Mechanistically, this is attributable to suppression of COX-2-derived prostacyclin (PGI2; ref. 6), which acts as a general restraint on endogenous stimuli, including platelet COX-1-derived thromboxane (Tx) A2, to platelet activation, vascular proliferation and remodeling, hypertension, atherogenesis, and cardiac function (7–13). Precise estimates of the incidence of this risk are not available. However, the relative risk is small and likely to be conditioned by such factors as drug exposure, underlying cardiovascular risk of the patients exposed and concomitant therapies (6, 13). However, the consumption of celecoxib, rofecoxib, and valdecoxib by millions has raised concern that many patients may have suffered cardiovascular adverse events from these drugs.

Inhibitors of COX-2 afford relief from pain and inflammation principally by suppressing prostaglandin (PG) E2 and PGI2. Deletion and/or antagonism of receptors for both of these PGs modulate the response to both painful and inflammatory stimuli (14–17). Although deletion of the PGI2 receptor, the I prostanoid receptor (IP), has revealed the important role that this PG plays in protection of cardiac and vascular function, the role of PGE2 is more complex. The effects of this PG are transduced by four E prostanoid receptors (EPs), which mediate contrasting biologies. Two of them, EP2 and EP4, are linked to Gs-mediated activation of adenylate cyclase, whereas the two others, EP1 and EP3, are linked to Gq and/or Gi (18). Deletion of EP2, just like the IP, results in salt-sensitive hypertension (9, 19), whereas EP4 mediates antiinflammatory effects, at least in vitro (20, 21). EP1 and EP3 mediate PGE2-induced vasoconstriction (22, 23), and PGE2 can either activate platelets by EP3 or, at higher concentrations, inhibit platelet aggregation by the IP (24). A further layer of complexity has been added by the observation that COX-2, EP4, and metalloproteinase (MMP) 9 are all up-regulated in human atherosclerotic plaque ex vivo (25), and that COX-2-dependent extracellular matrix-dependent activation of MMP9 is mediated by the EP4 in vitro (26).

The product of COX-catalyzed metabolism of arachidonic acid, PGH2, is metabolized further by specific synthases and isomerases to generate PGs (27). Microsomal (m)-PGE synthase (PGES)-1 (28, 29) is a member of the MAPEG (membrane-associated proteins involved in eicosanoid and glutathione metabolism) superfamily and has previously been suggested as a potential drug target (28). Two other PGES have also been identified, mPGES-2 (30) and cytosolic PGES-1 (31). Recently, mPGES-1 deletion in mice was found to modulate experimentally evoked pain and inflammation to a degree indistinguishable from treatment with traditional COX-nonspecific NSAIDs (32). This raises the possibility that specific inhibitors of mPGES-1 might retain the efficacy of NSAIDs, including those specific for inhibition of COX-2. However, given the contrasting effects of PGE2 on cardiovascular function, it is unclear whether such a strategy would bypass or diminish the risk evident in trials of NSAIDs specific for inhibition of COX-2. Recently, we have reported that mPGES-1 deletion, in contrast to deletion, disruption, or inhibition of COX-2, does not result in hypertension or a predisposition to thrombosis in normolipidemic mice (13). Here, we consider the impact of mPGES-1 deletion in hyperlipidemic mice. Studies with COX-2 inhibitors have described contrasting effects on atherogenesis in mice, perhaps reflecting variation among the drugs and doses used and both the timing and duration of the intervention (33). Here, we report that mPGES-1 is up-regulated in the vasculature during atherogenesis in mice lacking the receptor for low-density lipoprotein (LDLR). Deletion of mPGES-1 results in marked depletion of lesional macrophages and macrophage-derived foam cells, increased expression of vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) PGI2 synthase (PGIS), depression of endogenous PGE2, and an increase in systemic PGI2, but not Tx, biosynthesis. These results raise the possibility that drugs that inhibit specifically mPGES-1 may confer cardiovascular benefit, at least in part by rediversion of the COX product, PGH2, to vascular PGIS.

Results

mPGES-1 Deletion Retards Atherogenesis.

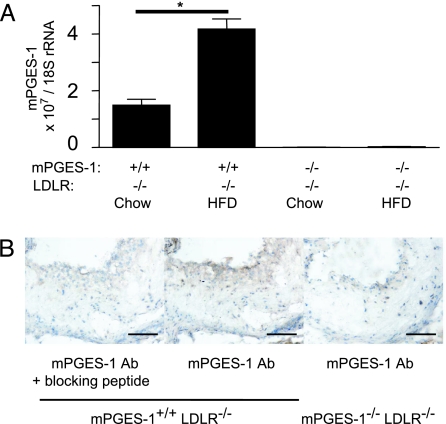

Neither a gender imbalance nor a genotype-associated developmental morbidity was observed when generating the double-knockout mice (mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−). Expression of aortic mPGES-1 transcripts increased ≈2-fold on high-fat diet (HFD; Fig. 1A). Correspondingly, immunostaining of the aortic root revealed mPGES-1 protein expressed in macrophages and macrophage-derived foam cells, particularly in the shoulder region of mPGES-1−/− plaques (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

mPGES-1 is induced during atherogenesis. (A) mPGES-1 expression was examined by real-time PCR in aorta from mice fed chow diet and after 6-mo HFD. Data shown are the mean ± SEM from duplicate determinations with n = 3 per group. ∗, P < 0.05. (B) mPGES-1 expression in an atherosclerotic lesion. Lesions from LDLR−/− and mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/− mice were stained with blocking peptide-preabsorbed mPGES-1 antibody (Left) and/or the antibody alone (Center and Right). (Scale bar, 100 μm.)

Starting at 8 wk of age, the mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/− and control mice (LDLR−/−) of both genders were fed a HFD for 3 or 6 mo. Total plasma cholesterol, triglycerides, and body weight were not different between mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−s and controls in either gender at any time point. All mice achieved a significant increase in plasma cholesterol during high-fat dietary feeding (Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

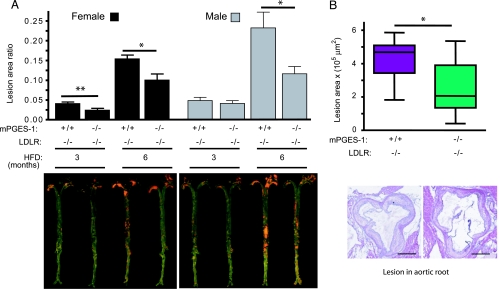

Deletion of mPGES-1 delayed atherogenesis significantly in both genders in LDLR−/−s (Fig. 2A). The lesion burden decreased in females by a mean 41% and 35% after 3 and 6 mo on HFD and in males by 15% and 50%, respectively. Consistent with the en face data, crosssectional analysis of aortic root samples revealed a significant decrease (34%) in the total lesion area in the aortic root from female mice fed HFD for 6 mo (Fig. 2B). mPGES-1 deletion did not affect blood pressure in either females [116.7 ± 5.2 mmHg in LDLR−/− vs. 113.3 ± 3.6 mmHg in mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/− (1 mmHg = 133 Pa)] or males (112.8 ± 3.3 mmHg in LDLR−/− vs. 113.4 ± 2.7 mmHg in mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−), as measured after 6 mo on the HFD (P > 0.8, n = 10–15 per group).

Fig. 2.

mPGES-1 deletion retards atherogenesis in LDLR−/− mice. (A) The extent of atherosclerosis, represented by the ratio of lesion area to total aortic area, was quantified by en face analysis of aortae from mice treated with a HFD for 3 or 6 mo (Upper). Representative en face graphs are shown (Lower), with each vertically matched to the corresponding data set in Upper. (B) Box-and-whiskers graph revealing the crosssectional analysis of aortic root samples from female mice after 6 mo on HFD, measuring total lesion area across the aortic root as detailed in Materials and Methods (Upper). A representative crosssection from each group is shown (Lower), vertically aligned with the corresponding data in Upper. (Scale bar, 500 μm.) ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01; n = 10–15 per group.

Lesional Morphology Consequent to mPGES-1 Deletion in LDLR−/− Mice.

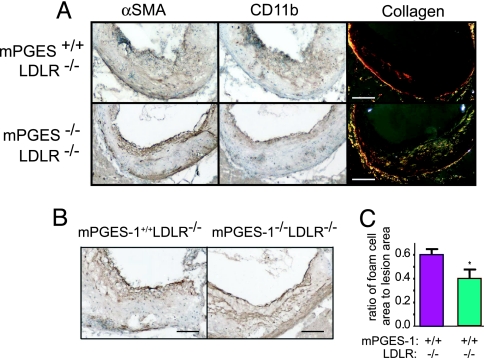

Macrophages, VSMCs, and collagen were immunostained in plaques of comparable size obtained at the aortic roots (Fig. 3). The VSMC content was variable in both groups, with no consistent difference observed between the groups in VSMC abundance (Fig. 3 A Left and B) or the percentage of lesion matrix rich (i.e., collagen) area. However, the birefringence of sirius red staining under polarized light indicates that the collagen that accumulates in the lesions of mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/− mice is in the form of mid-sized to large fibers (yellow to white reflection) typical of type I collagen compared with small fibers (red reflection) evident in the LDLR−/− (Fig. 3A Right). Strikingly, macrophages, as stained by CD11b (Fig. 3A Center), were depleted in lesions from the mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−s compared with littermate controls. Indeed, macrophage foam cells, as stained by CD11c antibody, occupied ≈60% of the total plaque area in LDLR−/−s, contrasting ≈40% in the mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−s (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Effects of mPGES-1 deletion on lesional morphology in LDLR−/− mice. Smooth muscle cells and macrophages were stained by antibodies against α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; A Left) and CD11b (A Center), respectively. Macrophages were depleted in the mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−s. Collagen content was stained by sirius red (A Right). Note the fibrillar collagen content of the mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/− neointima. All stainings in A were performed on one lesion of each genotype. Another set of α-SMA staining is shown in B. [Scale bar, 200 μm (A) and 100 μm (B).] Quantitative analysis (C) of macrophage-foam cells reveals a significant decrease in the ratio of foam cell area to lesion area. ∗, P = 0.02.

Both PGIS and thromboxane A2 (TxA2) synthase (TxS) were detectable in LDLR−/−s (Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). TxS was particularly evident in macrophage foam cells and PGIS in VSMC. Lesions obtained from mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−s had less TxS, reflecting macrophage depletion; they also exhibited less necrosis of the lesional core. Although structural integrity of the endothelium was retained over the disrupted sections of vasculature, and the endothelium was morphologically indistinguishable between the two groups, both PGIS and TxS were much more abundantly expressed in endothelium in the mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−s, suggesting a functional distinction. Endothelial localization of the two synthases was supported by apparent colocalization with lesional CD31 (platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule, PECAM). PGIS was relatively more abundant in mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/− lesions, probably due to macrophage depletion and the relative abundance of medial VSMCs, which are rich in the enzyme. Strikingly, VSMCs were radially orientated in mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/− lesions, perhaps reflecting the relative deficiency, compared with LDLR−/−, of migratory cues from necrotic or foam cell regions.

Differential Impact of mPGES-1 Deletion on Prostanoid Generation in Macrophages and VSMCs.

mPGES-1 was the primary source of PGE2 formation under basal conditions and after LPS stimulation of either macrophages or VSMCs (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). VSMCs were a more abundant source of 6-keto PGF1α (the hydrolysis product of PGI2) than macrophages under basal conditions. Also, the relative abundance of prostanoid formation in macrophages (PGE2 > TxB2 > 6-keto PGF1α) differed from that in VSMC (6-keto PGF1α > PGE2> TxB2).

Deletion of mPGES-1 depressed PGE2 and augmented LPS-stimulated 6-keto PGF1α and TxB2 in both cell types, although the principal redirection product in VSMC was PGI2, whereas TxA2 predominated in the macrophages. Indeed, under basal conditions, the only evidence of substrate shift detectable was a significant increase in 6-keto PGF1α production in VSMC.

mPGES-1 Deletion Decreases Systemic Biosynthesis of PGE2 and Augments PGI2.

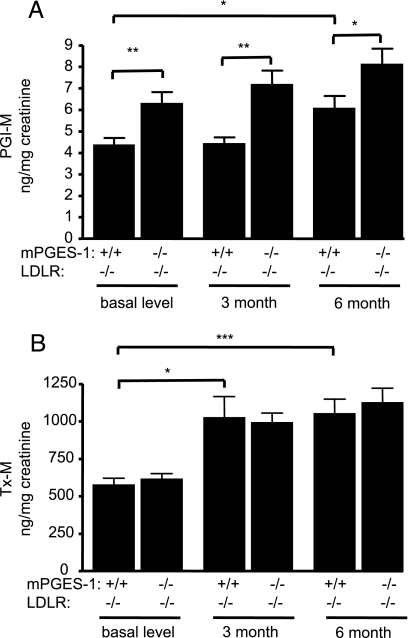

Systemic production of PGE2, TxA2, and PGI2 was determined by measuring their major urinary metabolites, 11α-hydroxy-9, 15-dioxo-2,3,4,5-tetranor-prostane-1,20-dioic acid (PGE-M), 2,3-dinor-TxB2 (Tx-M), and 2,3-dinor 6-keto PGF1α (PGI-M), respectively. mPGES-1 deletion significantly decreased PGE-M in the mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−s in each gender before HFD treatment (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Urinary Tx-M and PGI-M both increased during atherogenesis in LDLR−/−s (Fig. 4). Urinary PGI-M increased further in the mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−s, which was evident at all time points in the study, whereas excretion of Tx-M was unaltered. The significant depression of urinary PGE-M in mPGES-1-deleted mice was sustained on the HFD at 3 (12.33 ± 1.84 vs. 6.08 ± 1.05 ng/mg creatinine, P < 0.01 n = 14 and 16, respectively) and 6 mo (8.74 ± 0.99 vs. 5.16 ± 0.89 ng/mg creatinine, P < 0.05 n = 11 per group).

Fig. 4.

Biosynthesis of PGI2 and TxA2 during atherogenesis. Systemic production of PGI2 and TxA2 was examined by measuring their urinary metabolites, PGI-M and Tx-M. Both increased during atherogenesis in the LDLR−/− mice and substrate redirection to PGI2 (A), but not TxA2 (B), is observed in response to mPGES-1 deletion. This is sustained during the study period in hyperlipidemic mice. Data shown are from females. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001; n = 11–16 per group.

Discussion

Development of drugs that inhibit specifically mPGES-1 as alternatives to NSAIDs is configured on several assumptions. These include the premises that (i) mPGES-1 is a major source of the PGE2 formed in vivo, and that other PGES enzymes do not substitute for it when it is inhibited; (ii) an mPGES-1 inhibitor retains substantially the clinical efficacy of NSAIDs, despite the recognition that PGs other than PGE2, particularly PGI2, may contribute to pain and inflammation; (iii) the cardiovascular hazard attributable to specific inhibitors of COX-2 results from inhibition of PGI2 rather than PGE2; and (iv) the gastrointestinal consequences of mPGES-1 inhibition do not exceed those of NSAIDs, particularly those selective for COX-2.

The present study was designed to test some of these assumptions. We have previously reported that deletion of mPGES-1 depresses substantially endogenous PGE2 biosynthesis, as reflected by urinary PGE-M, in normolipidemic mice (13). Here, it is apparent that this observation extends to hyperlipidemic mice, and this inhibition is sustained as they develop atherosclerosis on a HFD. Thus, other PGES do not appear to substitute for the suppression of PGE2 formation consequent to mPGES-1 deletion.

We have previously reported that mPGES-1 deletion does not result in an elevation of blood pressure or enhance the response to thrombogenic stimuli in normolipidemic mice in which genetic manipulation or inhibition of COX-2 adversely influences both variables (13). Here again, we fail to observe a rise in blood pressure, this time when mPGES-1−/− mice are crossed into those lacking the LDLR. Indeed, deficiency in mPGES-1 does not adversely affect blood pressure during prolonged HFD feeding.

The impact of COX-2 deficiency on atherogenesis is complex. Investigators have reported that the development of plaque burden is accelerated, retarded, or uninfluenced by COX-2 inhibitors. These contrasting effects may reflect the contrasting biologies of the products of COX-2 formed by cells that predominate variably at different stages in disease evolution (33). Here, we observe that atherogenesis results in increased vascular expression of mPGES-1 in LDLR−/− mice. Deletion of mPGES-1 retards atherogenesis strikingly on an LDLR−/− background.

Lesion morphology is markedly altered in mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−s. Macrophages, themselves rich in COX-2, TxS, and mPGES-1, are markedly depleted. The VSMC content of the lesions, by contrast, is apparently unaltered. Interestingly, we observed changes in the type of collagen that accumulates in the atherosclerotic lesions, based on birefringence analysis of sirius-stained sections. Specifically, whereas lesions in LDLR−/−s have significant levels of smaller fibers, the mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/− lesions were enriched in fibrillar collagens (presumably type I, III, and or V), the predominant collagens produced by VSMC. These changes and the depletion of lesional macrophages are two of three morphological hallmarks of plaque stabilization (33), evident when mPGES-1 deletion occurs in hyperlipidemic mice. The third, enhanced formation of a fibrous cap, was not observed. However, there was no suggestion of plaque destabilization (25) in the mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−s. Expression of both PGIS and TxS is increased in endothelial cells, and the increase in the ratio of VSMCs relative to foam cells is associated with an increase in the proportion of neointimal cells expressing PGIS consequent to deletion of mPGES-1. Increased endothelial expression of both PGIS and TxS suggests removal of an mPGES-1-derived regulatory restraint on these enzymes in the mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−s.

Trebino et al. (34) have previously reported that synthesis of both TxA2 and PGI2 is increased in LPS-stimulated macrophages obtained from mPGES-1−/− mice ex vivo, which they attributed to rediversion of the accumulated PGH2 substrate to PGIS and TxS. Here, we replicate their observation in macrophages. Synthesis of both PGI2 and TxA2 is increased under LPS-stimulated conditions in mPGES-1-depleted macrophages. However, whereas this is also true of LPS-stimulated VSMCs, PGI2 is the more abundant product, and only PGI2 formation is increased in mPGES-1-depleted VSMC under basal conditions. Thus, the predominant product formed consequent to PGH2 rediversion due to mPGES-1 deletion or inhibition is likely to vary by cell type and pathophysiological condition (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Analysis of urinary metabolites represents a time-integrated noninvasive approach to the study of PG biosynthesis in vivo (35). Previously, we have shown that mPGES-1 deletion augments PGI2, but not TxA2, metabolite excretion in normolipidemic mice in which PGE2 biosynthesis is suppressed substantially. Here, we show that in the mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/−s, systemic biosynthesis of PGI2, but not TxA2, is augmented, and that this increase is sustained during atherogenesis. This may reflect the increased vascular expression of PGIS, together with depletion of lesional macrophages, a major source of TxA2 (36). Despite the marked gender difference in biosynthesis of PGE2, apparent both in normolipidemic and here in hyperlipidemic mice, the qualitative shift to an increase in PGI2 biosynthesis is apparent in both males and females. It is possible that initial manipulation of mPGES-1 when atherosclerosis is advanced and lesions are rich in macrophages might augment Tx biosynthesis. However, inducible deletion of the enzyme or timed intervention with a specific inhibitor would be necessary to address this hypothesis.

Previous studies have indicated that PGI2 is an important restraint on initiation and early development of atherogenesis in both male (10) and female (11) hyperlipidemic mice. This appears to reflect, at least in part, the induction of antioxidant enzymes, such as hemeoxygenase-1 (11, 37), which serve to counter free radical induced vascular injury consequent to platelet (10, 11) and neutrophil (10) activation. Furthermore, PGIS is uniquely susceptible to free radical-based inactivation (38), such as might pertain during atherogenesis. Although biosynthesis of PGI2 is augmented in patients with severe atherosclerosis (39), this reflects accelerated platelet and neutrophil–vessel wall interactions and stimulated production in response to physical and chemical stimuli. The capacity of atherosclerotic vascular tissue to produce PGI2, by contrast, is reduced compared with healthy vasculature (39). Biosynthesis of PGI2 is augmented by mPGES-1 deletion by ≈50% in both normolipidemic and hyperlipidemic mice. Although the functional relevance of this observation is unknown, haploinsufficiency of the IP results in a detectable cardiovascular phenotype (13), and increments in PGI2 biosynthesis of this order are often observed in settings of platelet activation where it may serve a homeostatic purpose (39).

These experiments indicate that mPGES-1-derived PGE2 accelerates atherogenesis in both male and female LDLR−/− mice. Experiments in mPGES-1−/− mice raise the possibility that selective inhibitors of this enzyme not only may reduce the likelihood of the hypertension and predisposition to thrombosis associated with COX-2 inhibitors but also may retain their clinical efficacy and even confer cardiovascular benefit during sustained dosing. The impact on atherogenesis may reflect depletion of lesional macrophages and foam cells, alterations in the nature of plaque collagen, and a relative increase in VSMC, rich in PGIS, facilitating substrate rediversion to augment systemic biosynthesis of PGI2. Although these results are encouraging, it remains to be determined whether specific inhibitors of mPGES-1 will retain the properties conferred by mPGES-1 deletion.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

mPGES-1−/− mice on DBA/1lacJ genetic background (32) were crossed with LDLR−/− mice fully backcrossed onto a C57BL/6 background (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), and the resulting mice (mPGES-1+/− LDLR+/−) were intercrossed to generate mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/− mice and their littermate controls (mPGES-1+/+ LDLR−/−). Mice used in these studies were on a ≈75% C57BL/6/25% DBA/1lacJ genetic background. All animals were housed according to guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee (IACUC) of the University of Pennsylvania, and all experiments were approved by the IACUC. Genotyping by PCR was derived from The Jackson Laboratory protocol (for ldlr) and from a previous publication for mpges-1 (32). Mice of both genders were started on a HFD (0.2% cholesterol/21% saturated fat; formula TD 88137, Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, IN) at 8 wk of age; subgroups were killed after 3 and 6 mo on the diet.

Blood Pressure Measurement.

Systolic blood pressure was measured in conscious mice by using a computerized noninvasive tail-cuff system (Visitech Systems, Apex, NC), as described (13). Blood pressure was recorded once each day between 15:00 and 18:00 for 4 consecutive days, and the average blood pressure was used.

Preparation of Mouse Aortae and Quantitation of Atherosclerosis.

Mice were killed, and the aortic tree was perfused with ice-cold PBS. The entire aorta (from the aortic root to the iliac bifurcation) was dissected out, fixed in buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH), cleaned of adventitial fat, opened longitudinally, and stained with Sudan IV (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The extent of atherosclerosis (Phase 3 Imaging Systems, Glen Mills, PA) was determined by using the en face method (40) and crosssectional analysis of lesion burden on aortic roots sections. Total lesion areas over 300 μm of the aortic root of nine mPGES-1−/− LDLR−/− mice and 11 LDLR−/− mice were measured on 8-μm (every 96 μm) acetone-fixed serial sections by using average lesion areas derived from three sections.

Lipid Analyses.

Blood was drawn by cardiac puncture from the killed mice, and EDTA (final concentration, 10 mM) was added immediately. Blood samples were obtained from animals at baseline after they fasted overnight by retroorbital bleeding with EDTA-coated Microvette 200 (Sarstedt, Newton, NC). Plasma total cholesterol and triglyceride levels were measured enzymatically on a Cobas Fara II autoanalyzer (Roche Diagnostic Systems, Nutley, NJ) by using Wako Chemicals (Richmond, VA) reagents.

Real-Time PCR Analysis of Gene Expression in Mouse Aorta.

TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for mPGES1 (Mm00452105_m1) were performed on an ABI Prism 7900 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Results were normalized with 18s rRNA (Hs99999901_s1).

Macrophage and VSMC Preparation.

Mice were injected i.p. with 3 ml of 3% thioglycollate media and killed after 4 days. Peritoneal lavages were collected, filtered, centrifuged at 1,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, and resuspended in phenol-free RPMI medium 1640 (Invitrogen Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were plated onto six-well plates, incubated at 37°C for 4 h, and then changed into serum-free media overnight. VSMCs were isolated from mouse aorta as described (11) and incubated in serum-free media overnight. Cells were treated the next day with fresh serum-free media with LPS (Sigma-Aldrich L-2654 from Escherichia coli 026:B6, 1 μg/ml in PBS) or PBS (control) and then incubated for 24 h. Cell culture media were used for prostanoid determination.

Histological Examination of Lesion Morphology.

Fixed and peroxidase-quenched sections (8 μm) of OCT compound-embedded tissue were blocked with 20 μg/ml goat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), followed by incubation with primary antibodies: rabbit antilaminin, FITC-conjugated mouse anti-α-smooth muscle actin clone 1A4 (Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-mPGES-1, rabbit anti-PGIS, rabbit anti-TxS (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI), biotinylated hamster anti-CD11c, rat anti-CD11b, or rat anti-platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (anti-PECAM) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Sections were then incubated with either biotinylated mouse anti-rabbit, mouse anti-rat, or mouse anti-FITC (Jackson ImmunoResearch), followed by Vectastain ABC avidin-biotin amplification (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and developed with diaminobenzidine (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). All sections were counterstained with Gill’s Formulation no. 1 hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific), and isotype controls were run in parallel with negligible staining observed in all cases. Eosin was obtained from Fisher Scientific, and Sirius Direct Red 80 was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Crosssectional analysis for macrophage foam cells (CD11c) was performed every 96 μm over 300 μm of the aortic root of five mice for each group.

Analysis of Prostanoids and Their Metabolites.

Urine was collected for 24 h at baseline and again after 3 and 6 mo of HFD feeding. Systemic production of PGE2, TxA2, and PGI2 was determined by mass spectrometric quantitation of their major urinary metabolites: 7-hydroxy-5,11-diketotetranorprostane-1,16-dioic acid (PGE-M), Tx-M, and PGI-M, respectively. Briefly, 100 μl of urine was spiked with the corresponding stable isotope labeled internal standard: d6-PGE-M, 18O2-2,3-dinor TxB2 and d3-2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α, allowed to react with mythoxylamine, purified with solid-phase extraction by using Strata-X cartridges (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA), and subjected to HPLC and tandem mass spectrometry (Quantum Ultra, ThermoFinnigan, San Jose, CA). The following mass transitions were monitored: m/z 385→336 (PGE-M), m/z 391→342 (d6-PGE-M), m/z 370→155 (2,3-dinor TxB2), m/z 374→155 (18O2-2,3-dinor TxB2), m/z 370→232 (2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α), and m/z 373→235 (d3-2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α). Quantification of the endogenous metabolites was used the ratio of the peak areas of the analytes and their respective internal standards. Data were corrected for urinary creatinine (Oxford Biomedical Research, Oxford, MI).

Statistical Analysis.

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons of multiple groups were performed by ANOVA and a Dunn’s post-ANOVA multiple comparison test when the ANOVA was significant. When only two mean values were compared, the two-tailed Mann–Whitney t test was used. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Technical support was kindly provided by Helen Zou and Ping Liu. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Karine Egan, Julien Ferrari, and John Lawson. mPGES-1−/− mice were generously supplied by Dr. L. Audoly (Pfizer, New York, NY). This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (Grants HL 70128, HL 62250, and 2-P01-HL-06225). G.A.F. holds the Elmer Bobst Chair of Pharmacology.

Abbreviations

- PG

prostaglandin

- PGES

PGE synthase

- mPGES

microsomal PGES

- PGE-M, 11α-hydroxy-9, 15-dioxo-2,3,4,5-tetranor-prostane-1,20-dioic acid

- LDLR

low-density lipoprotein receptor

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cell

- PGI2

prostacyclin

- PGIS

PGI2 synthase

- Tx

thromboxane

- TxS

Tx synthase

- PGI-M, 2,3-dinor 6-keto PGF1α

- Tx-M

2,3-dinor-TxB2

- NSAID

nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- EP

E prostanoid receptor

- HFD

high-fat diet

- TxA2

thromboxane A2

- IP

I prostanoid receptor

- TxS

TxA2 synthase.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: G.A.F. receives financial support for investigator-initiated research from Bayer, Merck, and Boehringer Ingelheim, all of which manufacture drugs that target COXs. G.A.F. is a member of the Steering Committee of the Multinational Etoricoxib and Diclofenac Arthritis Long-Term (MEDAL) Study Program. G.A.F. also serves as a consultant for Bayer, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Genome Institute of the Novartis Foundation, Boehringer Ingelheim, and NicOx.

References

- 1.Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, Shapiro D, Burgos-Vargas R, Davis B, Day R, Ferraz MB, Hawkey CJ, Hochberg MC, et al. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1520–1528. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432103. 2 p following 1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, Bolognese JA, Oxenius B, Horgan K, Lines C, Riddell R, Morton D, Lanas A, et al. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1092–1102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, Wittes J, Fowler R, Finn P, Anderson WF, Zauber A, Hawk E, Bertagnolli M. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1071–1080. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furberg CD, Psaty BM, FitzGerald GA. Circulation. 2005;111:249. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155081.76164.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anonymous. Public Citizen. 2005 www.citizen.org/publications/release.cfm?ID=7358. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grosser T, Fries S, FitzGerald GA. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:4–15. doi: 10.1172/JCI27291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng Y, Austin SC, Rocca B, Koller BH, Coffman TM, Grosser T, Lawson JA, FitzGerald GA. Science. 2002;296:539–541. doi: 10.1126/science.1068711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudic RD, Brinster D, Cheng Y, Fries S, Song WL, Austin S, Coffman TM, FitzGerald GA. Circ Res. 2005;96:1240–1247. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000170888.11669.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francois H, Athirakul K, Howell D, Dash R, Mao L, Kim HS, Rockman HA, FitzGerald GA, Koller BH, Coffman TM. Cell Metab. 2005;2:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi T, Tahara Y, Matsumoto M, Iguchi M, Sano H, Murayama T, Arai H, Oida H, Yurugi-Kobayashi T, Yamashita JK, et al. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:784–794. doi: 10.1172/JCI21446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egan KM, Lawson JA, Fries S, Koller B, Rader DJ, Smyth EM, FitzGerald GA. Science. 2004;306:1954–1957. doi: 10.1126/science.1103333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hennan JK, Huang J, Barrett TD, Driscoll EM, Willens DE, Park AM, Crofford LJ, Lucchesi BR. Circulation. 2001;104:820–825. doi: 10.1161/hc3301.092790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng Y, Wang M, Yu Y, Lawson J, Funk CD, FitzGerald GA. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1391–1399. doi: 10.1172/JCI27540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takasaki I, Nojima H, Shiraki K, Sugimoto Y, Ichikawa A, Ushikubi F, Narumiya S, Kuraishi Y. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moriyama T, Higashi T, Togashi K, Iida T, Segi E, Sugimoto Y, Tominaga T, Narumiya S, Tominaga M. Mol Pain. 2005;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murata T, Ushikubi F, Matsuoka T, Hirata M, Yamasaki A, Sugimoto Y, Ichikawa A, Aze Y, Tanaka T, Yoshida N, et al. Nature. 1997;388:678–682. doi: 10.1038/41780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honda T, Segi-Nishida E, Miyachi Y, Narumiya S. J Exp Med. 2006;203:325–335. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ushikubi F, Segi E, Sugimoto Y, Murata T, Matsuoka T, Kobayashi T, Hizaki H, Tuboi K, Katsuyama M, Ichikawa A, et al. Nature. 1998;395:281–284. doi: 10.1038/26233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy CR, Zhang Y, Brandon S, Guan Y, Coffee K, Funk CD, Magnuson MA, Oates JA, Breyer MD, Breyer RM. Nat Med. 1999;5:217–220. doi: 10.1038/5583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takayama K, Garcia-Cardena G, Sukhova GK, Comander J, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Libby P. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44147–44154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takayama K, Sukhova GK, Chin MT, Libby P. Circ Res. 2006;98:499–504. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000204451.88147.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norel X, de Montpreville V, Brink C. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2004;74:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jadhav V, Jabre A, Lin SZ, Lee TJ. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:1305–1316. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000139446.61789.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fabre JE, Nguyen M, Athirakul K, Coggins K, McNeish JD, Austin S, Parise LK, FitzGerald GA, Coffman TM, Koller BH. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:603–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cipollone F, Fazia ML, Iezzi A, Cuccurullo C, De Caesere D, Uccino S, Spigonardo F, Marchetti A, Buttita F, Paloscia L, et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1925–1931. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000177814.41505.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pavlovic S, Du B, Sakamoto K, Khan KM, Natarajan C, Breyer RM, Dannenberg AJ, Falcone DJ. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3321–3328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Funk CD. Science. 2001;294:1871–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jakobsson PJ, Thoren S, Morgenstern R, Samuelsson B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7220–7225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thoren S, Weinander R, Saha S, Jegerschold C, Pettersson PL, Samuelsson B, Hebert H, Hamberg M, Morgenstern R, Jakobsson PJ. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22199–22209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murakami M, Kudo I. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:943–954. doi: 10.2174/138161206776055912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pini B, Grosser T, Lawson JA, Price TS, Pack MA, FitzGerald GA. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:315–320. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000152355.97808.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trebino CE, Stock JL, Gibbons CP, Naiman BM, Wachtmann TS, Umland JP, Pandher K, Lapointe JM, Saha S, Roach ML, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9044–9049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332766100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Egan KM, Wang M, Fries S, Lucitt MB, Zukas AM, Pure E, Lawson JA, FitzGerald GA. Circulation. 2005;111:334–342. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153386.95356.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trebino CE, Eskra JD, Wachtmann TS, Perez JR, Carty TJ, Audoly LP. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16579–16585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412075200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.FitzGerald GA, Pedersen AK, Patrono C. Circulation. 1983;67:1174–1177. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.6.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burleigh ME, Babaev VR, Oates JA, Harris RC, Gautam S, Riendeau D, Marnett LJ, Morrow JD, Fazio S, Linton MF. Circulation. 2002;105:1816–1823. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014927.74465.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyer-Kirchrath J, Debey S, Glandorff C, Kirchrath L, Schror K. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67:757–765. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zou MH, Shi C, Cohen RA. Diabetes. 2002;51:198–203. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.FitzGerald GA, Smith B, Pedersen AK, Brash AR. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1065–1068. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198404263101701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tangirala RK, Rubin EM, Palinski W. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:2320–2328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.