Abstract

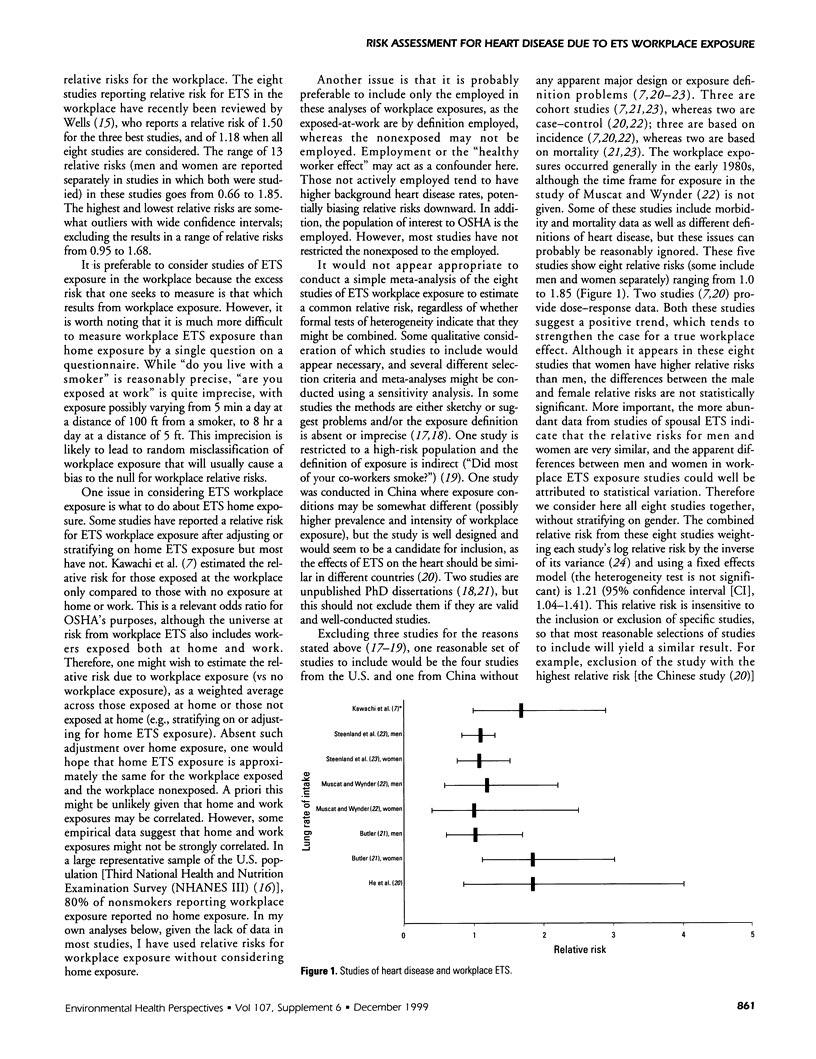

In 1994 the U.S. Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) published a study of risk assessment for heart disease and lung cancer resulting from workplace exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) among nonsmokers. This assessment is currently being revised. The present article considers different possible approaches to a risk assessment for heart disease among nonsmokers resulting from workplace ETS exposure, reviews the approach taken by OSHA in 1994, and suggests some modifications to that approach. Since 1994 the literature supporting an association between ETS exposure and heart disease among never smokers (sometimes including long-term former smokers) has been strengthened by new studies, including some studies that have specifically considered workplace exposure. A number of these studies are appropriate for inclusion in a meta-analysis, whereas a few may not be due to methodological problems or problems in exposure definition. A meta-analysis of eight relative risks (either rate ratios or odds ratios) for heart disease resulting from workplace ETS exposure, based on one reasonable selection of appropriate studies, yields a combined relative risk of 1.21 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04-1.41). This relative risk, which is similar to that used by OSHA in 1994, yields an excess risk of death from heart disease by age 70 of 7 per 1000 (95% CI 0.001-0.013) resulting from ETS exposure in the workplace. This excess risk exceeds OSHA's usual threshold for regulation of 1 per 1000. Approximately 1,710 excess ischemic heart disease deaths per year would be expected among nonsmoking U.S. workers 35-69 years of age exposed to workplace ETS.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Colditz G. A., Burdick E., Mosteller F. Heterogeneity in meta-analysis of data from epidemiologic studies: a commentary. Am J Epidemiol. 1995 Aug 15;142(4):371–382. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings K. M., Markello S. J., Mahoney M., Bhargava A. K., McElroy P. D., Marshall J. R. Measurement of current exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Arch Environ Health. 1990 Mar-Apr;45(2):74–79. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1990.9935929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson A. J., Alexander H. M., Heller R. F., Lloyd D. M. Passive smoking and the risk of heart attack or coronary death. Med J Aust. 1991 Jun 17;154(12):793–797. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1991.tb121366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gail M. Measuring the benefit of reduced exposure to environmental carcinogens. J Chronic Dis. 1975 Mar;28(3):135–147. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(75)90002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach K. K., Shopland D. R., Hartman A. M., Gibson J. T., Pechacek T. F. Workplace smoking policies in the United States: results from a national survey of more than 100,000 workers. Tob Control. 1997 Autumn;6(3):199–206. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.3.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz S. A., Parmley W. W. Passive smoking and heart disease. Mechanisms and risk. JAMA. 1995 Apr 5;273(13):1047–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond S. K. Exposure of U.S. workers to environmental tobacco smoke. Environ Health Perspect. 1999 May;107 (Suppl 2):329–340. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107s2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond S. K., Sorensen G., Youngstrom R., Ockene J. K. Occupational exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. JAMA. 1995 Sep 27;274(12):956–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsing K. J., Sandler D. P., Comstock G. W., Chee E. Heart disease mortality in nonsmokers living with smokers. Am J Epidemiol. 1988 May;127(5):915–922. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard G., Burke G. L., Szklo M., Tell G. S., Eckfeldt J., Evans G., Heiss G. Active and passive smoking are associated with increased carotid wall thickness. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Arch Intern Med. 1994 Jun 13;154(11):1277–1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I., Colditz G. A., Speizer F. E., Manson J. E., Stampfer M. J., Willett W. C., Hennekens C. H. A prospective study of passive smoking and coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1997 May 20;95(10):2374–2379. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.10.2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M. R., Morris J. K., Wald N. J. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and ischaemic heart disease: an evaluation of the evidence. BMJ. 1997 Oct 18;315(7114):973–980. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7114.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscat J. E., Wynder E. L. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and the risk of heart attack. Int J Epidemiol. 1995 Aug;24(4):715–719. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.4.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkle J. L., Flegal K. M., Bernert J. T., Brody D. J., Etzel R. A., Maurer K. R. Exposure of the US population to environmental tobacco smoke: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988 to 1991. JAMA. 1996 Apr 24;275(16):1233–1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repace J. L., Lowrey A. H. An enforceable indoor air quality standard for environmental tobacco smoke in the workplace. Risk Anal. 1993 Aug;13(4):463–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1993.tb00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenland K. Passive smoking and the risk of heart disease. JAMA. 1992 Jan 1;267(1):94–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenland K., Thun M., Lally C., Heath C., Jr Environmental tobacco smoke and coronary heart disease in the American Cancer Society CPS-II cohort. Circulation. 1996 Aug 15;94(4):622–628. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.4.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillman F. A., Becker D. M., Swank R. T., Hantula D., Moses H., Glantz S., Waranch H. R. Ending smoking at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. An evaluation of smoking prevalence and indoor air pollution. JAMA. 1990 Sep 26;264(12):1565–1569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen K. H., Kuller L. H., Martin M. J., Ockene J. K. Effects of passive smoking in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Am J Epidemiol. 1987 Nov;126(5):783–795. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trout D., Decker J., Mueller C., Bernert J. T., Pirkle J. Exposure of casino employees to environmental tobacco smoke. J Occup Environ Med. 1998 Mar;40(3):270–276. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199803000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall-Pedoe H., Brown C. A., Woodward M., Tavendale R. Passive smoking by self report and serum cotinine and the prevalence of respiratory and coronary heart disease in the Scottish heart health study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995 Apr;49(2):139–143. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.2.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waard F., Kemmeren J. M., van Ginkel L. A., Stolker A. A. Urinary cotinine and lung cancer risk in a female cohort. Br J Cancer. 1995 Sep;72(3):784–787. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]