Abstract

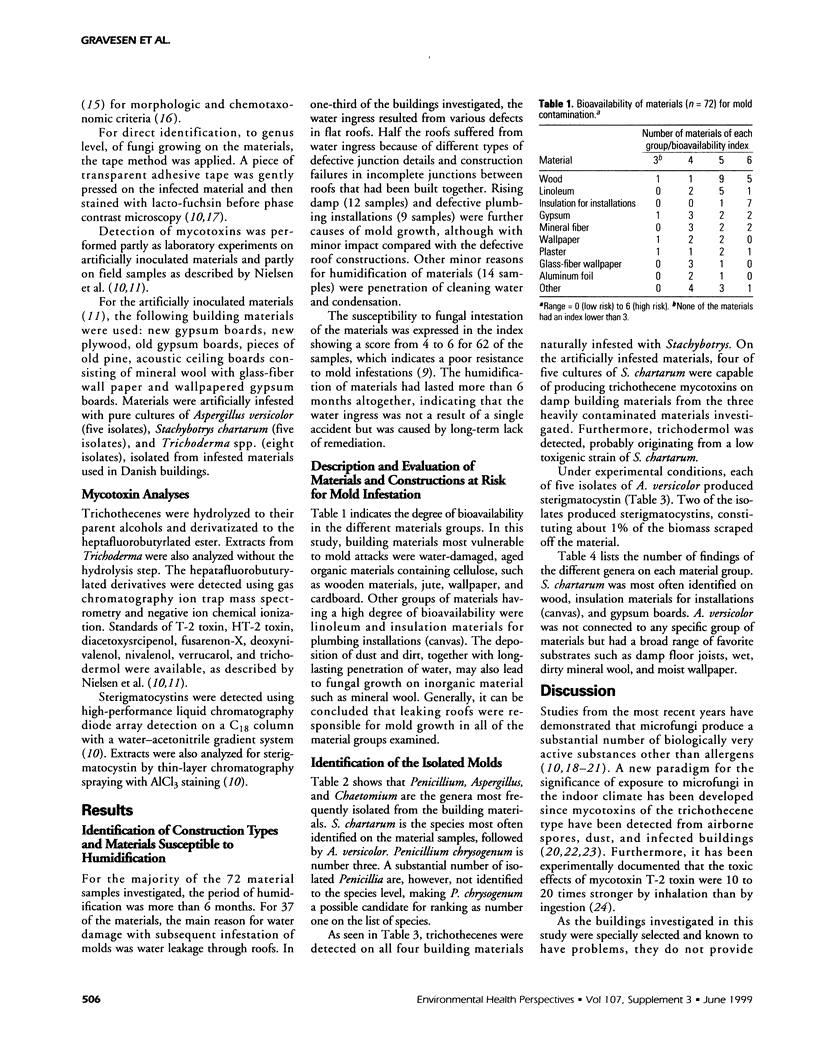

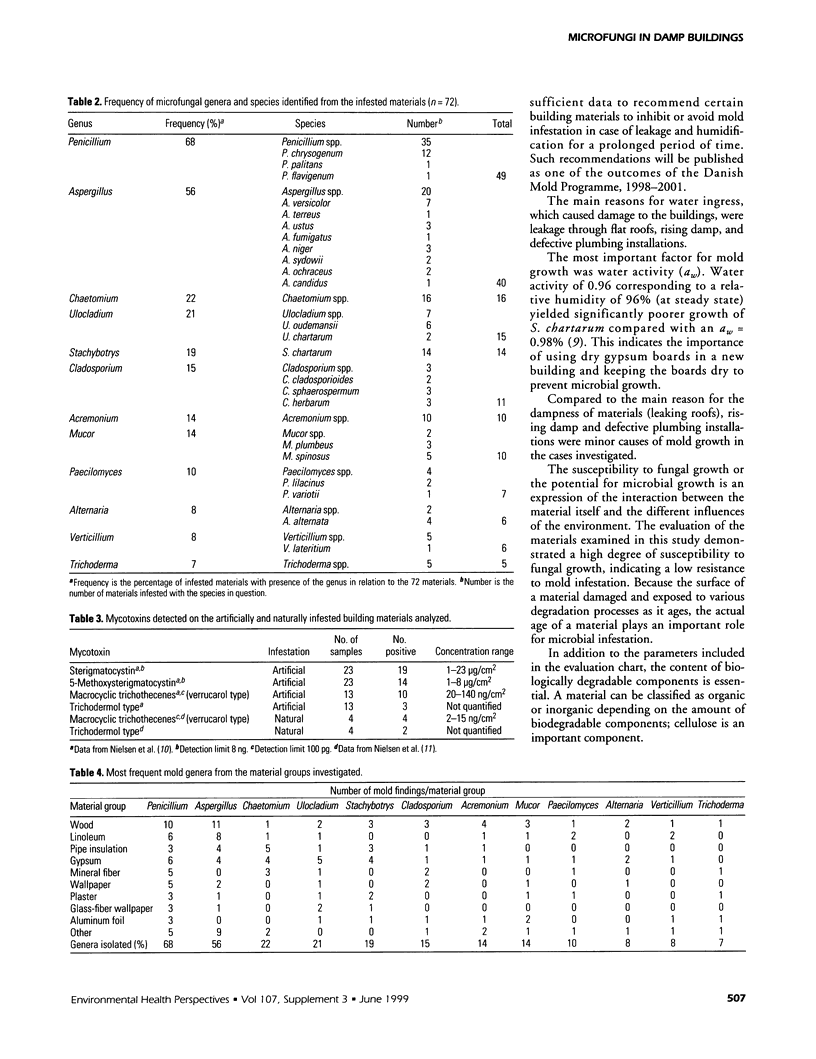

To elucidate problems with microfungal infestation in indoor environments, a multidisciplinary collaborative pilot study, supported by a grant from the Danish Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, was performed on 72 mold-infected building materials from 23 buildings. Water leakage through roofs, rising damp, and defective plumbing installations were the main reasons for water damage with subsequent infestation of molds. From a score system assessing the bioavailability of the building materials, products most vulnerable to mold attacks were water damaged, aged organic materials containing cellulose, such as wooden materials, jute, wallpaper, and cardboard. The microfungal genera most frequently encountered were Penicillium (68%), Aspergillus (56%), Chaetomium (22%), Ulocladium, (21%), Stachybotrys (19%) and Cladosporium (15%). Penicillium chrysogenum, Aspergillus versicolor, and Stachybotrys chartarum were the most frequently occurring species. Under field conditions, several trichothecenes were detected in each of three commonly used building materials, heavily contaminated with S. chartarum. Under experimental conditions, four out of five isolates of S. chartarum produced satratoxin H and G when growing on new and old, very humid gypsum boards. A. versicolor produced the carcinogenic mycotoxin sterigmatocystin and 5-methoxysterigmatocystin under the same conditions.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brunekreef B., Dockery D. W., Speizer F. E., Ware J. H., Spengler J. D., Ferris B. G. Home dampness and respiratory morbidity in children. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989 Nov;140(5):1363–1367. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.5.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creasia D. A., Thurman J. D., Jones L. J., 3rd, Nealley M. L., York C. G., Wannemacher R. W., Jr, Bunner D. L. Acute inhalation toxicity of T-2 mycotoxin in mice. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1987 Feb;8(2):230–235. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(87)90121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dales R. E., Miller D., McMullen E. Indoor air quality and health: validity and determinants of reported home dampness and moulds. Int J Epidemiol. 1997 Feb;26(1):120–125. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dales R. E., Zwanenburg H., Burnett R., Franklin C. A. Respiratory health effects of home dampness and molds among Canadian children. Am J Epidemiol. 1991 Jul 15;134(2):196–203. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etzel R. A., Montaña E., Sorenson W. G., Kullman G. J., Allan T. M., Dearborn D. G., Olson D. R., Jarvis B. B., Miller J. D. Acute pulmonary hemorrhage in infants associated with exposure to Stachybotrys atra and other fungi. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998 Aug;152(8):757–762. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.8.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad J. C., Filtenborg O. Classification of terverticillate penicillia based on profiles of mycotoxins and other secondary metabolites. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983 Dec;46(6):1301–1310. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.6.1301-1310.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husman T. Health effects of indoor-air microorganisms. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1996 Feb;22(1):5–13. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola J. J., Jaakkola N., Ruotsalainen R. Home dampness and molds as determinants of respiratory symptoms and asthma in pre-school children. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1993;3 (Suppl 1):129–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanning E., Biagini R., Hull D., Morey P., Jarvis B., Landsbergis P. Health and immunology study following exposure to toxigenic fungi (Stachybotrys chartarum) in a water-damaged office environment. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1996;68(4):207–218. doi: 10.1007/BF00381430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikulin M., Pasanen A. L., Berg S., Hintikka E. L. Stachybotrys atra Growth and Toxin Production in Some Building Materials and Fodder under Different Relative Humidities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994 Sep;60(9):3421–3424. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.9.3421-3424.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson R. A. Occurrence of moulds in modern living and working environments. Eur J Epidemiol. 1985 Mar;1(1):54–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00162313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strachan D. P., Sanders C. H. Damp housing and childhood asthma; respiratory effects of indoor air temperature and relative humidity. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1989 Mar;43(1):7–14. doi: 10.1136/jech.43.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]