Abstract

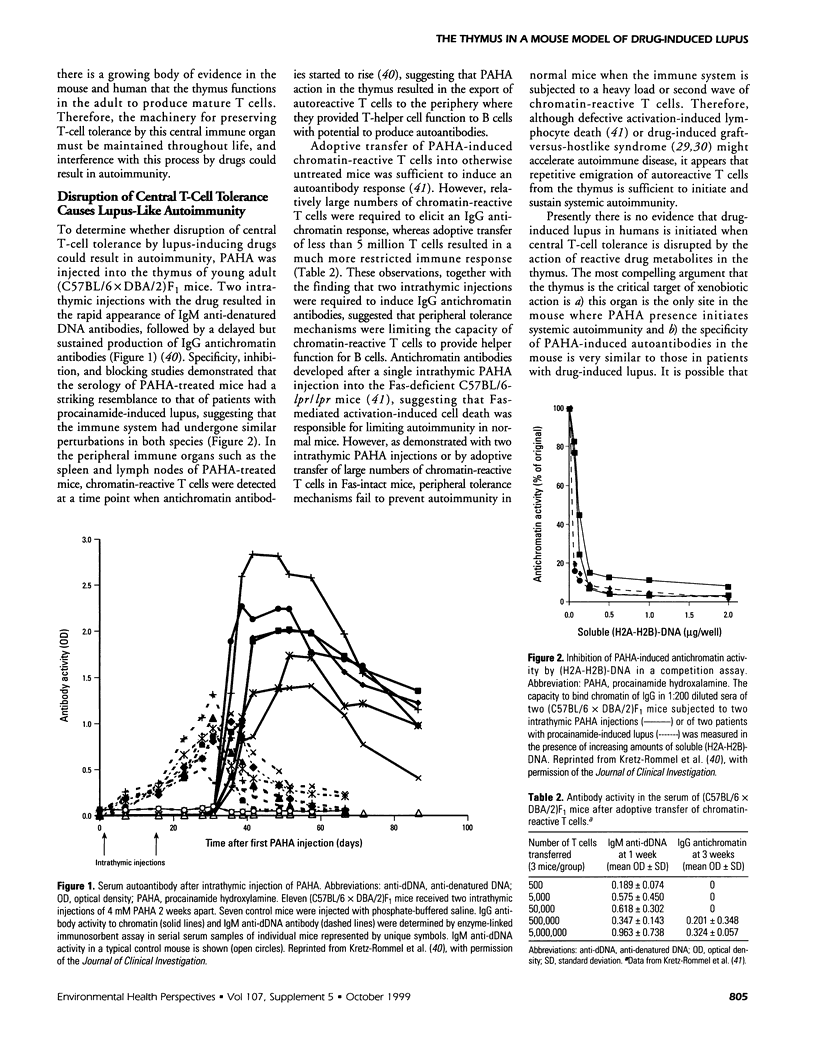

Drug-induced lupus is a side effect of deliberate ingestion of various medications, but its etiology, underlying mechanisms, and pathogenesis are puzzling. In vivo metabolic transformation of lupus-inducing drugs to reactive products explains how a heterogeneous set of drugs can mediate the same disease syndrome. Evidence has accumulated that drugs are transformed by extracellular oxidation from reactive oxygen species and myeloperoxidase produced when neutrophils are activated, maximizing the in situ accumulation of reactive drug metabolites within lymphoid compartments. The metabolite of procainamide, procainamide hydroxylamine, displays diverse biologic properties, but no apparent autoimmune effect has been observed. However, when procainamide hydroxylamine was introduced into the thymus of young adult normal mice, a delayed but robust autoimmune response developed. Disruption of central T-cell tolerance by intrathymic procainamide hydroxylamine resulted in the production of chromatin-reactive T cells that apparently drove the autoantibody response in the periphery. Drug-induced autoantibodies in this mouse model were remarkably similar to those in patients with procainamide-induced lupus. Therefore, this system has considerable promise to provide insight into the initiating events in drug-induced lupus and may provide a paradigm for how other xenobiotics might induce systemic autoimmunity.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adams L. E., Roberts S. M., Carter J. M., Wheeler J. F., Zimmer H. W., Donovan-Brand R. J., Hess E. V. Effects of procainamide hydroxylamine on generation of reactive oxygen species by macrophages and production of cytokines. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1990;12(7):809–819. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(90)90045-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams L. E., Sanders C. E., Jr, Budinsky R. A., Donovan-Brand R., Roberts S. M., Hess E. V. Immunomodulatory effects of procainamide metabolites: their implications in drug-related lupus. J Lab Clin Med. 1989 Apr;113(4):482–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr D. P., Aust S. D. On the mechanism of peroxidase-catalyzed oxygen production. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993 Jun;303(2):377–382. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertho J. M., Demarquay C., Moulian N., Van Der Meeren A., Berrih-Aknin S., Gourmelon P. Phenotypic and immunohistological analyses of the human adult thymus: evidence for an active thymus during adult life. Cell Immunol. 1997 Jul 10;179(1):30–40. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1997.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budinsky R. A., Roberts S. M., Coats E. A., Adams L., Hess E. V. The formation of procainamide hydroxylamine by rat and human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1987 Jan-Feb;15(1):37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUSTAN H. P., TAYLOR R. D., CORCORAN A. C. Rheumatic and febrile syndrome during prolonged hydralazine treatment. J Am Med Assoc. 1954 Jan 2;154(1):23–29. doi: 10.1001/jama.1954.02940350025006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douek D. C., McFarland R. D., Keiser P. H., Gage E. A., Massey J. M., Haynes B. F., Polis M. A., Haase A. T., Feinberg M. B., Sullivan J. L. Changes in thymic function with age and during the treatment of HIV infection. Nature. 1998 Dec 17;396(6712):690–695. doi: 10.1038/25374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleichmann E., Gleichmann H., Wilke W. Autoimmunization and lymphomagenesis in parent to F1 combinations differing at the major histocompatibility complex: model for spontaneous disease caused by altered self-antigens? Transplant Rev. 1976;31:156–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1976.tb01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Quintial R., Theofilopoulos A. N. V beta gene repertoires in aging mice. J Immunol. 1992 Jul 1;149(1):230–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstra A. H., Li-Muller S. M., Uetrecht J. P. Metabolism of isoniazid by activated leukocytes. Possible role in drug-induced lupus. Drug Metab Dispos. 1992 Mar-Apr;20(2):205–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstra A. H., Matassa L. C., Uetrecht J. P. Metabolism of hydralazine by activated leukocytes: implications for hydralazine induced lupus. J Rheumatol. 1991 Nov;18(11):1673–1680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Khursigara G., Rubin R. L. Transformation of lupus-inducing drugs to cytotoxic products by activated neutrophils. Science. 1994 Nov 4;266(5186):810–813. doi: 10.1126/science.7973636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelder P. P., de Mol N. J., 'T Hart B. A., Janssen L. H. Metabolic activation of chlorpromazine by stimulated human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Induction of covalent binding of chlorpromazine to nucleic acids and proteins. Chem Biol Interact. 1991;79(1):15–30. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(91)90049-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretz-Rommel A., Duncan S. R., Rubin R. L. Autoimmunity caused by disruption of central T cell tolerance. A murine model of drug-induced lupus. J Clin Invest. 1997 Apr 15;99(8):1888–1896. doi: 10.1172/JCI119356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretz-Rommel A., Rubin R. L. Persistence of autoreactive T cell drive is required to elicit anti-chromatin antibodies in a murine model of drug-induced lupus. J Immunol. 1999 Jan 15;162(2):813–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicka-Muranyi M., Goebels R., Goebel C., Uetrecht J., Gleichmann E. T lymphocytes ignore procainamide, but respond to its reactive metabolites in peritoneal cells: demonstration by the adoptive transfer popliteal lymph node assay. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1993 Sep;122(1):88–94. doi: 10.1006/taap.1993.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORROW J. D., SCHROEDER H. A., PERRY H. M., Jr Studies on the control of hypertension by hyphex. II. Toxic reactions and side effects. Circulation. 1953 Dec;8(6):829–839. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.8.6.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackall C. L., Punt J. A., Morgan P., Farr A. G., Gress R. E. Thymic function in young/old chimeras: substantial thymic T cell regenerative capacity despite irreversible age-associated thymic involution. Eur J Immunol. 1998 Jun;28(6):1886–1893. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199806)28:06<1886::AID-IMMU1886>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magner-Wróbel K., Toborek M., Drózdz M., Danch A. Increase in antioxidant activity in procainamide-treated rats. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1993 Feb;72(2):94–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1993.tb00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pircher H., Rohrer U. H., Moskophidis D., Zinkernagel R. M., Hengartner H. Lower receptor avidity required for thymic clonal deletion than for effector T-cell function. Nature. 1991 Jun 6;351(6326):482–485. doi: 10.1038/351482a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl L. R., Satoh H., Christ D. D., Kenna J. G. The immunologic and metabolic basis of drug hypersensitivities. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1988;28:367–387. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.28.040188.002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quddus J., Johnson K. J., Gavalchin J., Amento E. P., Chrisp C. E., Yung R. L., Richardson B. C. Treating activated CD4+ T cells with either of two distinct DNA methyltransferase inhibitors, 5-azacytidine or procainamide, is sufficient to cause a lupus-like disease in syngeneic mice. J Clin Invest. 1993 Jul;92(1):38–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI116576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlins M. D. Clinical pharmacology. Adverse reactions to drugs. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981 Mar 21;282(6268):974–976. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6268.974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S. M., Adams L. E., Donovan-Brand R., Budinsky R., Skoulis N. P., Zimmer H., Hess E. V. Procainamide hydroxylamine lymphocyte toxicity--I. Evidence for participation by hemoglobin. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1989;11(4):419–427. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(89)90089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin R. L., Curnutte J. T. Metabolism of procainamide to the cytotoxic hydroxylamine by neutrophils activated in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1989 Apr;83(4):1336–1343. doi: 10.1172/JCI114020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin R. L., Uetrecht J. P., Jones J. E. Cytotoxicity of oxidative metabolites of procainamide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987 Sep;242(3):833–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann G. G. Changes in the human thymus during aging. Curr Top Pathol. 1986;75:43–88. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-82480-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streeter A. J., Timbrell J. A. Enzyme-mediated covalent binding of hydralazine to rat liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1983 May-Jun;11(3):179–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetrecht J. P. Reactivity and possible significance of hydroxylamine and nitroso metabolites of procainamide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985 Feb;232(2):420–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetrecht J. P., Sweetman B. J., Woosley R. L., Oates J. A. Metabolism of procainamide to a hydroxylamine by rat and human hepatic microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1984 Jan-Feb;12(1):77–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetrecht J., Sokoluk B. Comparative metabolism and covalent binding of procainamide by human leukocytes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1992 Jan-Feb;20(1):120–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetrecht J., Zahid N., Rubin R. Metabolism of procainamide to a hydroxylamine by human neutrophils and mononuclear leukocytes. Chem Res Toxicol. 1988 Jan-Feb;1(1):74–78. doi: 10.1021/tx00001a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldhauser L., Uetrecht J. Oxidation of propylthiouracil to reactive metabolites by activated neutrophils. Implications for agranulocytosis. Drug Metab Dispos. 1991 Mar-Apr;19(2):354–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y., Naiki M., Wilson T., Godfrey D., Chiang B. L., Boyd R., Ansari A., Gershwin M. E. Thymic microenvironmental abnormalities and thymic selection in NZB.H-2bm12 mice. J Immunol. 1993 May 15;150(10):4702–4712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg K., Annett G., Kashyap A., Lenarsky C., Forman S. J., Parkman R. The effect of thymic function on immunocompetence following bone marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1995 Nov;1(1):18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler J. F., Lunte C. E., Heineman W. R., Adams L., Hess E. V. Electrochemical determination of N-oxidized procainamide metabolites and functional assessment of effects on murine cells in vitro. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1988 Jul;188(3):381–386. doi: 10.3181/00379727-188-3-rc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K., Kawanishi S. Free radical production and site-specific DNA damage induced by hydralazine in the presence of metal ions or peroxidase/hydrogen peroxide. 1991 Mar 15-Apr 1Biochem Pharmacol. 41(6-7):905–914. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90195-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung R. L., Quddus J., Chrisp C. E., Johnson K. J., Richardson B. C. Mechanism of drug-induced lupus. I. Cloned Th2 cells modified with DNA methylation inhibitors in vitro cause autoimmunity in vivo. J Immunol. 1995 Mar 15;154(6):3025–3035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]