Abstract

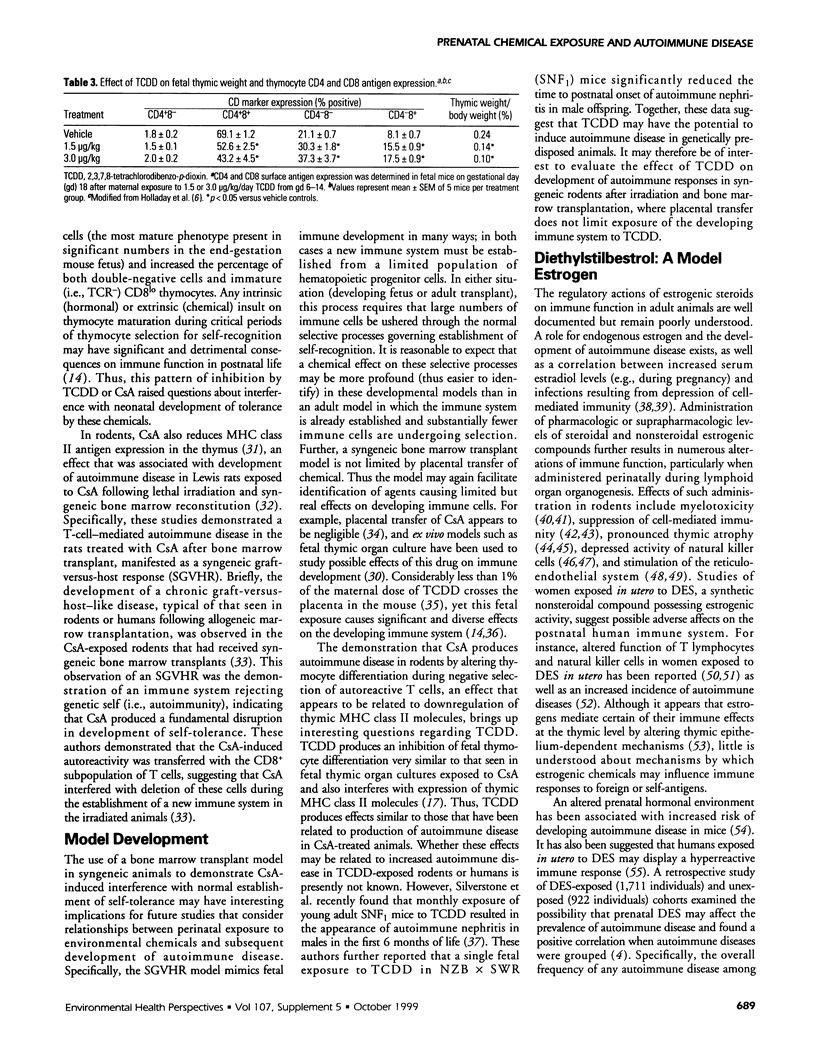

Reports in humans and rodents indicate that immune development may be altered following perinatal exposure to immunotoxic compounds, including chemotherapeutics, corticosteroids, polycyclic hydrocarbons, and polyhalogenated hydrocarbons. Effects from such exposure may be more dramatic or persistent than following exposure during adult life. For example, prenatal exposure to the insecticide chlordane or to the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon benzo[(italic)a(/italic)]pyrene produces what appears to be lifelong immunosuppression in mice. Whether prenatal immunotoxicant exposure may predispose the organism to postnatal autoimmune disease remains largely unknown. In this regard, the therapeutic immunosuppressant cyclosporin A (CsA) crosses the placenta poorly. However, lethally irradiated rodents exposed to CsA postsyngeneic bone marrow transplant (i.e., during re-establishment of the immune system) develop T-cell-mediated autoimmune disease, suggesting this drug may produce a fundamental disruption in development of self-tolerance by T cells. The environmental contaminant 2,3,7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-(italic)p(/italic)-dioxin (TCDD) crosses the placenta and produces fetal thymic effects (italic)in vivo(/italic) similar to effects of CsA in fetal thymic organ culture, including inhibited thymocyte maturation and reduced expression of thymic major histocompatability complex class II molecules. These observations led to the suggestion that gestational exposure to TCDD may interfere with normal development of self-tolerance. Possibly supporting this hypothesis, when mice predisposed to development of autoimmune disease were treated with TCDD during gestation, postnatal autoimmunity was exacerbated. Similar results have been reported for mice exposed to diethylstilbestrol during development. These reports suggest that prenatal exposure to certain immunotoxicants may play a role in postnatal expression of autoimmunity.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aboussaouira T., Marie C., Brugal G., Idelman S. Inhibitory effect of 17 beta-estradiol on thymocyte proliferation and metabolic activity in young rats. Thymus. 1991 May;17(3):167–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R. E., Tokuda S., Williams W. L., Warner N. L. Radiation-induced augmentation of the response of A/J mice to SaI tumor cells. Am J Pathol. 1982 Jul;108(1):24–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird D. D., Wilcox A. J., Herbst A. L. Self-reported allergy, infection, and autoimmune diseases among men and women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996 Feb;49(2):263–266. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00521-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball J. K., Dawson D. A. Biological effects of the neonatal injection of 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1969 Apr;42(4):579–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billingham R. E. The biology of graft-versus-host reactions. Harvey Lect. 1966;62:21–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaylock B. L., Holladay S. D., Comment C. E., Heindel J. J., Luster M. I. Exposure to tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) alters fetal thymocyte maturation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1992 Feb;112(2):207–213. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(92)90189-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boorman G. A., Luster M. I., Dean J. H., Wilson R. E. The effect of adult exposure to diethylstilbestrol in the mouse on macrophage function and numbers. J Reticuloendothel Soc. 1980 Dec;28(6):547–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrier D. E., Ziprin R. L. Immunotoxic effects of T-2 mycotoxin on cell-mediated resistance to Listeria monocytogenes infection. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1987 Jan;14(1):11–21. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(87)90071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Waal E. J., Schuurman H. J., Loeber J. G., Van Loveren H., Vos J. G. Alterations in the cortical thymic epithelium of rats after in vivo exposure to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD): an (immuno)histological study. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1992 Jul;115(1):80–88. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(92)90370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dencker L., Hassoun E., d'Argy R., Alm G. Fetal thymus organ culture as an in vitro model for the toxicity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and its congeners. Mol Pharmacol. 1985 Jan;27(1):133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descotes J. The popliteal lymph node assay: a tool for studying the mechanisms of drug-induced autoimmune disorders. Toxicol Lett. 1992 Dec;64-65 Spec No:101–107. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(92)90178-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong L., Ma Q., Whitlock J. P., Jr Down-regulation of major histocompatibility complex Q1b gene expression by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. J Biol Chem. 1997 Nov 21;272(47):29614–29619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith R. E., Moore J. A. Impairment of thymus-dependent immune functions by exposure of the developing immune system to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). J Toxicol Environ Health. 1977 Oct;3(3):451–464. doi: 10.1080/15287397709529578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith R. E., Moore J. A. Impairment of thymus-dependent immune functions by exposure of the developing immune system to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). J Toxicol Environ Health. 1977 Oct;3(3):451–464. doi: 10.1080/15287397709529578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan F., Pinson D. M., Rozman K. K. Immunomodulatory effect of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin tested by the popliteal lymph node assay. Toxicol Pathol. 1995 Jul-Aug;23(4):513–517. doi: 10.1177/019262339502300408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine J. S., Gasiewicz T. A., Silverstone A. E. Lymphocyte stem cell alterations following perinatal exposure to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Mol Pharmacol. 1989 Jan;35(1):18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C. D., Johnson G. H., Smith W. G. Natural killer cells in in utero diethylstilbesterol-exposed patients. Gynecol Oncol. 1983 Dec;16(3):400–404. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(83)90168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C. D., Johnson G. H., Smith W. G. Natural killer cells in in utero diethylstilbesterol-exposed patients. Gynecol Oncol. 1983 Dec;16(3):400–404. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(83)90168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried W., Tichler T., Dennenberg I., Barone J., Wang F. Effects of estrogens on hematopoietic stem cells and on hematopoiesis of mice. J Lab Clin Med. 1974 May;83(5):807–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlee W. F., Dold K. M., Irons R. D., Osborne R. Evidence for direct action of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) on thymic epithelium. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1985 Jun 15;79(1):112–120. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(85)90373-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenman D. L., Dooley K., Breeden C. R. Strain differences in the response of the mouse to diethylstilbestrol. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1977 Oct;3(3):589–597. doi: 10.1080/15287397709529591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman C. J., Roselle G. A. The interrelationship of the HPG-thymic axis and immune system regulation. J Steroid Biochem. 1983 Jul;19(1B):461–467. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(83)90204-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. S., Hellström I. Altered immune responses in pregnant mice. Transplantation. 1977 May;23(5):423–430. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197705000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanawa H., Tsuchida M., Matsumoto Y., Watanabe H., Abo T., Sekikawa H., Kodama M., Zhang S., Izumi T., Shibata A. Characterization of T cells infiltrating the heart in rats with experimental autoimmune myocarditis. Their similarity to extrathymic T cells in mice and the site of proliferation. J Immunol. 1993 Jun 15;150(12):5682–5695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess A. D., Fischer A. C., Beschorner W. E. Effector mechanisms in cyclosporine A-induced syngeneic graft-versus-host disease. Role of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets. J Immunol. 1990 Jul 15;145(2):526–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess A. D., Horwitz L., Beschorner W. E., Santos G. W. Development of graft-vs.-host disease-like syndrome in cyclosporine-treated rats after syngeneic bone marrow transplantation. I. Development of cytotoxic T lymphocytes with apparent polyclonal anti-Ia specificity, including autoreactivity. J Exp Med. 1985 Apr 1;161(4):718–730. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.4.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holladay S. D., Blaylock B. L., Comment C. E., Heindel J. J., Fox W. M., Korach K. S., Luster M. I. Selective prothymocyte targeting by prenatal diethylstilbesterol exposure. Cell Immunol. 1993 Nov;152(1):131–142. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1993.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holladay S. D., Lindstrom P., Blaylock B. L., Comment C. E., Germolec D. R., Heindell J. J., Luster M. I. Perinatal thymocyte antigen expression and postnatal immune development altered by gestational exposure to tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). Teratology. 1991 Oct;44(4):385–393. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420440405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holladay S. D., Luster M. I. Alterations in fetal thymic and liver hematopoietic cells as indicators of exposure to developmental immunotoxicants. Environ Health Perspect. 1996 Aug;104 (Suppl 4):809–813. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104s4809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husmann L. A., Shimonkevitz R. P., Crispe I. N., Bevan M. J. Thymocyte subpopulations during early fetal development in the BALB/c mouse. J Immunol. 1988 Aug 1;141(3):736–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakkanaiah V. N., Pyle R. H., Nagarkatti M., Nagarkatti P. S. Evidence for major alterations in the thymocyte subpopulations in murine models of autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 1990 Jun;3(3):271–288. doi: 10.1016/0896-8411(90)90146-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalland T., Forsberg J. G. Natural killer cell activity and tumor susceptibility in female mice treated neonatally with diethylstilbestrol. Cancer Res. 1981 Dec;41(12 Pt 1):5134–5140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalland T., Fossberg T. M., Forsberg J. G. Effect of estrogen and corticosterone on the lymphoid system in neonatal mice. Exp Mol Pathol. 1978 Feb;28(1):76–95. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(78)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalland T. Reduced natural killer activity in female mice after neonatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol. J Immunol. 1980 Mar;124(3):1297–1300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi A., Zuniga-Pflucker J. C., Sharrow S. O., Kruisbeek A. M., Shearer G. M. Effect of cyclosporin A on lymphopoiesis. II. Developmental defects of immature and mature thymocytes in fetal thymus organ cultures treated with cyclosporin A. J Immunol. 1989 Nov 15;143(10):3134–3140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruisbeek A. M., Bridges S., Carmen J., Longo D. L., Mond J. J. In vivo treatment of neonatal mice with anti-I-A antibodies interferes with the development of the class I, class II, and Mls-reactive proliferating T cell subset. J Immunol. 1985 Jun;134(6):3597–3604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur S., Mathur R. S., Goust J. M., Williamson H. O., Fudenberg H. H. Cyclic variations in white cell subpopulations in the human menstrual cycle: correlations with progesterone and estradiol. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1979 Jul;13(3):246–253. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(79)90069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICOL T., BILBEY D. L., CHARLES L. M., CORDINGLEY J. L., VERNON-ROBERTS B. OESTROGEN: THE NATURAL STIMULANT OF BODY DEFENCE. J Endocrinol. 1964 Oct;30:277–291. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0300277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandakumaran M., Eldeen A. S. Transfer of cyclosporine in the perfused human placenta. Dev Pharmacol Ther. 1990;15(2):101–105. doi: 10.1159/000457628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nau H., Bass R. Transfer of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) to the mouse embryo and fetus. Toxicology. 1981;20(4):299–308. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(81)90037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noller K. L., Blair P. B., O'Brien P. C., Melton L. J., 3rd, Offord J. R., Kaufman R. H., Colton T. Increased occurrence of autoimmune disease among women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. Fertil Steril. 1988 Jun;49(6):1080–1082. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59965-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noller K. L., Blair P. B., O'Brien P. C., Melton L. J., 3rd, Offord J. R., Kaufman R. H., Colton T. Increased occurrence of autoimmune disease among women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. Fertil Steril. 1988 Jun;49(6):1080–1082. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59965-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyama R., Abo T., Seki S., Ohteki T., Sugiura K., Kusumi A., Kumagai K. Estrogen administration activates extrathymic T cell differentiation in the liver. J Exp Med. 1992 Mar 1;175(3):661–669. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.3.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penit C., Vasseur F. Cell proliferation and differentiation in the fetal and early postnatal mouse thymus. J Immunol. 1989 May 15;142(10):3369–3377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poland A., Knutson J. C. 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and related halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons: examination of the mechanism of toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1982;22:517–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.22.040182.002505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha B., Vassalli P., Guy-Grand D. The extrathymic T-cell development pathway. Immunol Today. 1992 Nov;13(11):449–454. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90074-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlumpf M., Ramseier H., Lichtensteiger W. Prenatal diazepam induced persisting depression of cellular immune responses. Life Sci. 1989;44(7):493–501. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90465-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuurman H. J., Van Loveren H., Rozing J., Vos J. G. Chemicals trophic for the thymus: risk for immunodeficiency and autoimmunity. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1992 Apr;14(3):369–375. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(92)90166-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman W. E., Merigan T. C., Talal N. Natural killing in estrogen-treated mice responds poorly to poly I.C despite normal stimulation of circulating interferon. J Immunol. 1979 Dec;123(6):2903–2905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone A. E., Frazier D. E., Jr, Gasiewicz T. A. Alternate immune system targets for TCDD: lymphocyte stem cells and extrathymic T-cell development. Exp Clin Immunogenet. 1994;11(2-3):94–101. doi: 10.1159/000424198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talal N. Lessons from autoimmunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993 Aug 12;690:19–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb43991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urso P., Gengozian N. Subnormal expression of cell-mediated and humoral immune responses in progeny disposed toward a high incidence of tumors after in utero exposure to benzo[a]pyrene. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1984;14(4):569–584. doi: 10.1080/15287398409530606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker S. E., Keisler L. W., Caldwell C. W., Kier A. B., vom Saal F. S. Effects of altered prenatal hormonal environment on expression of autoimmune disease in NZB/NZW mice. Environ Health Perspect. 1996 Aug;104 (Suppl 4):815–821. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104s4815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ways S. C., Bern H. A. Longterm effects of neonatal treatment with cortisol and/or estrogen in the female BALB/c mouse. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1979 Jan;160(1):94–98. doi: 10.3181/00379727-160-40396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ways S. C., Mortola J. F., Zvaifler N. J., Weiss R. J., Yen S. S. Alterations in immune responsiveness in women exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero. Fertil Steril. 1987 Aug;48(2):193–197. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59341-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ways S. C., Mortola J. F., Zvaifler N. J., Weiss R. J., Yen S. S. Alterations in immune responsiveness in women exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero. Fertil Steril. 1987 Aug;48(2):193–197. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59341-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingard D. L., Turiel J. Long-term effects of exposure to diethylstilbestrol. West J Med. 1988 Nov;149(5):551–554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Heer C., van Driesten G., Schuurman H. J., Rozing J., van Loveren H. No evidence for emergence of autoreactive V beta 6+ T cells in Mls-1a mice following exposure to a thymotoxic dose of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Toxicology. 1995 Dec 10;103(3):195–203. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(95)03135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]