Abstract

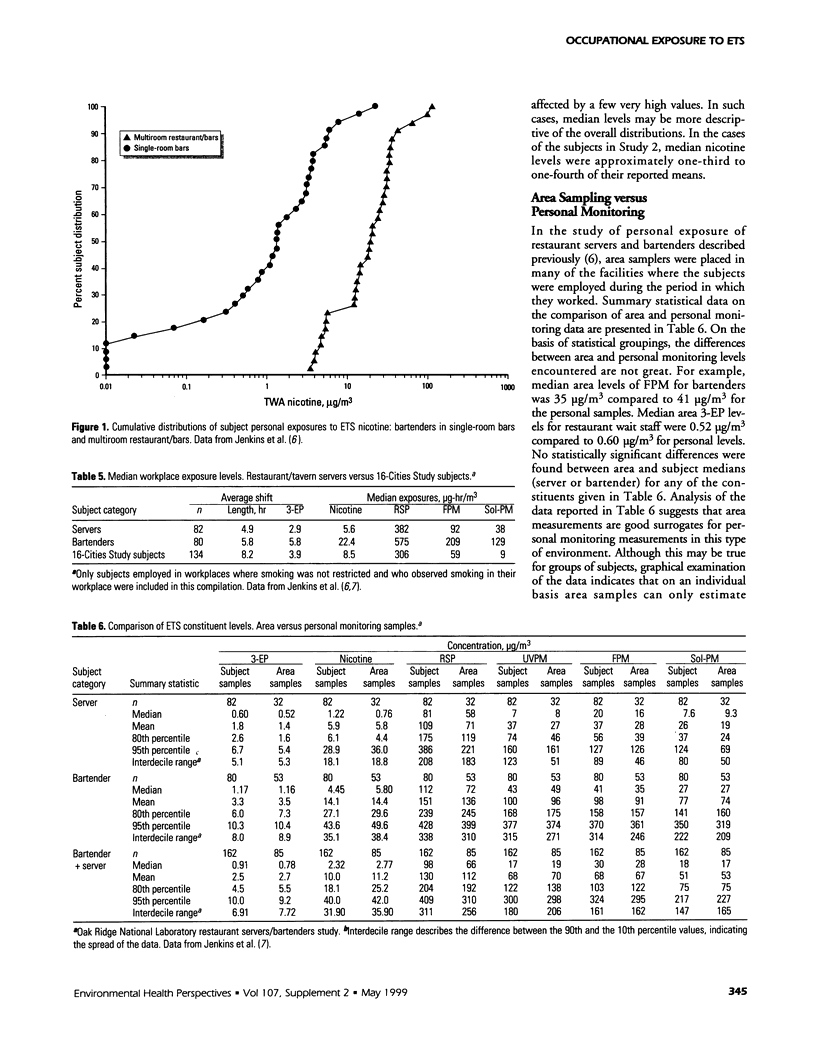

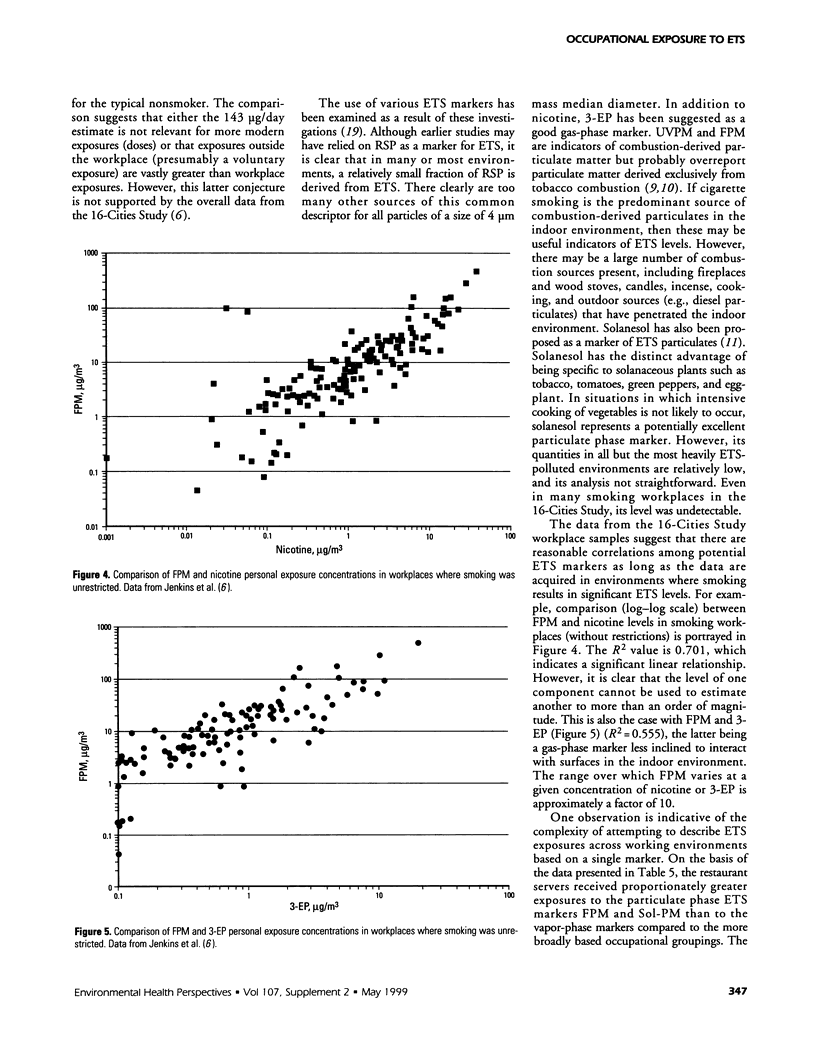

Personal monitoring is a more accurate measure of individual exposure to airborne constituents because it incorporates human activity patterns and collects actual breathing zone samples to which subjects are exposed. Two recent studies conducted by our laboratory offer perspective on occupational exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) from a personal exposure standpoint. In a study of nearly 1600 workers, levels of ETS were lower than or comparable to those in earlier studies. Limits on smoking in designated areas also acted to reduce overall exposure of workers. In facilities where smoking is permitted, ETS exposures are 10 to 20 times greater than in facilities in which smoking is banned. Service workers were exposed to higher levels of ETS than workers in white-collar occupations. For the narrower occupational category of waiters, waitresses, and bartenders, a second study in one urban location indicated that ETS levels to which wait staff are exposed are not considerably different from those exposure levels of subjects in the larger study who work in environments in which smoking is unrestricted. Bartenders were exposed to higher ETS levels, but there is a distinction between bartenders working in smaller facilities and those working in multiroom restaurant bars, with the former exposed to higher levels of ETS than the latter. In addition, ETS levels encountered by these more highly exposed workers are lower that those estimated by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Concomitant area monitoring in the smaller study suggests that area samples can only be used to estimate individual personal exposure to within an order of magnitude or greater.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bergman T. A., Johnson D. L., Boatright D. T., Smallwood K. G., Rando R. J. Occupational exposure of nonsmoking nightclub musicians to environmental tobacco smoke. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1996 Aug;57(8):746–752. doi: 10.1080/15428119691014611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coultas D. B., Samet J. M., McCarthy J. F., Spengler J. D. A personal monitoring study to assess workplace exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Am J Public Health. 1990 Aug;80(8):988–990. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.8.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond S. K., Sorensen G., Youngstrom R., Ockene J. K. Occupational exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. JAMA. 1995 Sep 27;274(12):956–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins R. A., Palausky A., Counts R. W., Bayne C. K., Dindal A. B., Guerin M. R. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in sixteen cities in the United States as determined by personal breathing zone air sampling. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1996 Oct-Dec;6(4):473–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repace J. L., Lowrey A. H. An enforceable indoor air quality standard for environmental tobacco smoke in the workplace. Risk Anal. 1993 Aug;13(4):463–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1993.tb00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M. Involuntary smoking in the restaurant workplace. A review of employee exposure and health effects. JAMA. 1993 Jul 28;270(4):490–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]