Abstract

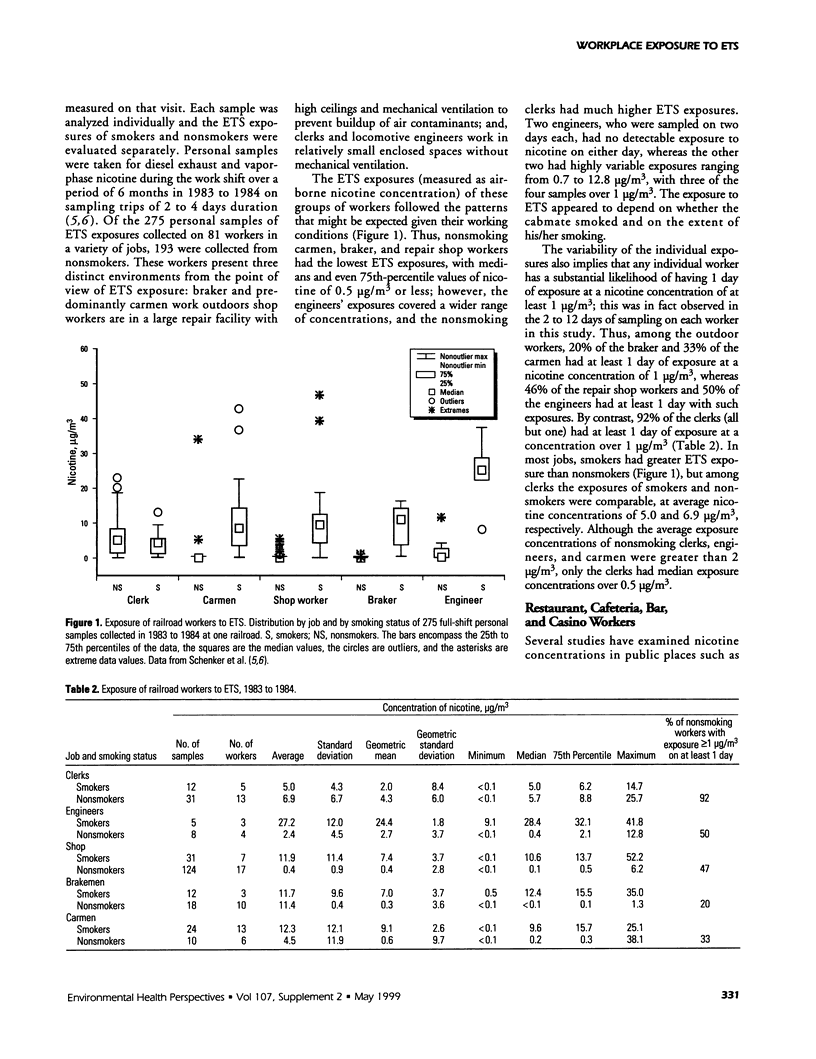

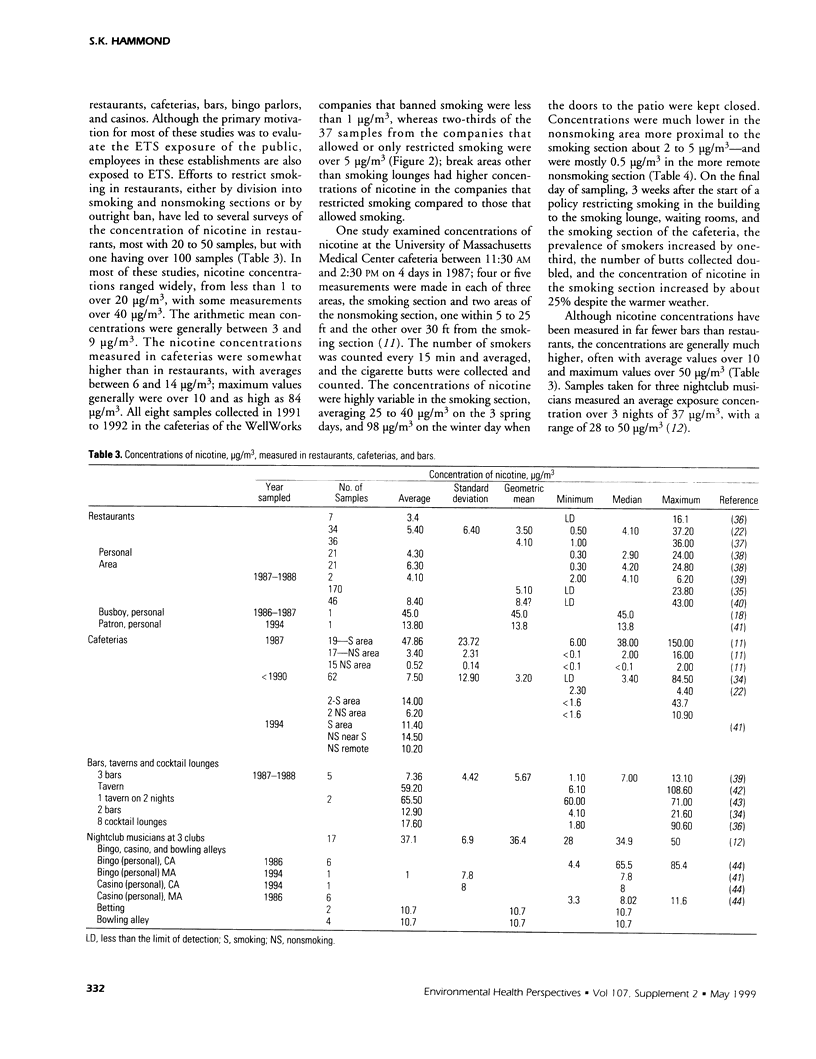

The concentrations of environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) to which workers are exposed have been measured, using nicotine or other tracers, in diverse workplaces. Policies restricting workplace smoking to a few designated areas have been shown to reduce concentrations of ETS, although the effectiveness of such policies varies among work sites. Policies that ban smoking in the workplace are the most effective and generally lower all nicotine concentrations to less than 1 microg/m3; by contrast, mean concentrations measured in workplaces that allow smoking generally range from 2 to 6 microg/m3 in offices, from 3 to 8 microg/m3 in restaurants, and from 1 to 6 microg/m3 in the workplaces of blue-collar workers. Mean nicotine concentrations from 1 to 3 microg/m3 have been measured in the homes of smokers. Furthermore, workplace concentrations are highly variable, and some concentrations are more than 10 times higher than the average home levels, which have been established to cause lung cancer, heart disease, and other adverse health effects. For the approximately 30% of workers exposed to ETS in the workplace but not in the home, workplace exposure is the principal source of ETS. Among those with home exposures, exposures at work may exceed those resulting from home. We conclude that a significant number of U.S. workers are exposed to hazardous levels of ETS.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bergman T. A., Johnson D. L., Boatright D. T., Smallwood K. G., Rando R. J. Occupational exposure of nonsmoking nightclub musicians to environmental tobacco smoke. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1996 Aug;57(8):746–752. doi: 10.1080/15428119691014611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coultas D. B., Samet J. M., McCarthy J. F., Spengler J. D. A personal monitoring study to assess workplace exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Am J Public Health. 1990 Aug;80(8):988–990. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.8.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daisey J. M. Tracers for assessing exposure to environmental tobacco smoke: what are they tracing? Environ Health Perspect. 1999 May;107 (Suppl 2):319–327. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107s2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontham E. T., Correa P., Reynolds P., Wu-Williams A., Buffler P. A., Greenberg R. S., Chen V. W., Alterman T., Boyd P., Austin D. F. Environmental tobacco smoke and lung cancer in nonsmoking women. A multicenter study. JAMA. 1994 Jun 8;271(22):1752–1759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond S. K., Smith T. J., Woskie S. R., Leaderer B. P., Bettinger N. Markers of exposure to diesel exhaust and cigarette smoke in railroad workers. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1988 Oct;49(10):516–522. doi: 10.1080/15298668891380150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond S. K., Sorensen G., Youngstrom R., Ockene J. K. Occupational exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. JAMA. 1995 Sep 27;274(12):956–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson F. W., Reid H. F., Morris R., Wang O. L., Hu P. C., Helms R. W., Forehand L., Mumford J., Lewtas J., Haley N. J. Home air nicotine levels and urinary cotinine excretion in preschool children. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989 Jul;140(1):197–201. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins R. A., Counts R. W. Occupational exposure to environmental tobacco smoke: results of two personal exposure studies. Environ Health Perspect. 1999 May;107 (Suppl 2):341–348. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107s2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins R. A., Palausky A., Counts R. W., Bayne C. K., Dindal A. B., Guerin M. R. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in sixteen cities in the United States as determined by personal breathing zone air sampling. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1996 Oct-Dec;6(4):473–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kado N. Y., McCurdy S. A., Tesluk S. J., Hammond S. K., Hsieh D. P., Jones J., Schenker M. B. Measuring personal exposure to airborne mutagens and nicotine in environmental tobacco smoke. Mutat Res. 1991 Sep;261(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(91)90100-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kromhout H., Symanski E., Rappaport S. M. A comprehensive evaluation of within- and between-worker components of occupational exposure to chemical agents. Ann Occup Hyg. 1993 Jun;37(3):253–270. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/37.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marbury M. C., Hammond S. K., Haley N. J. Measuring exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in studies of acute health effects. Am J Epidemiol. 1993 May 15;137(10):1089–1097. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M. E., Boyd G., Byar D., Brown C., Callahan J. F., Corle D., Cullen J. W., Greenblatt J., Haley N. J., Hammond K. Passive smoking on commercial airline flights. JAMA. 1989 Feb 10;261(6):867–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesner E. A., Rudnick S. N., Hu F. C., Spengler J. D., Preller L., Ozkaynak H., Nelson W. Particulate and nicotine sampling in public facilities and offices. JAPCA. 1989 Dec;39(12):1577–1582. doi: 10.1080/08940630.1989.10466652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu M., Umemura S., Okada T., Tomita H. Estimation of personal exposure to tobacco smoke with a newly developed nicotine personal monitor. Environ Res. 1984 Oct;35(1):218–227. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(84)90130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkle J. L., Flegal K. M., Bernert J. T., Brody D. J., Etzel R. A., Maurer K. R. Exposure of the US population to environmental tobacco smoke: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988 to 1991. JAMA. 1996 Apr 24;275(16):1233–1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repace J. L., Jinot J., Bayard S., Emmons K., Hammond S. K. Air nicotine and saliva cotinine as indicators of workplace passive smoking exposure and risk. Risk Anal. 1998 Feb;18(1):71–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1998.tb00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repace J. L., Lowrey A. H. Indoor air pollution, tobacco smoke, and public health. Science. 1980 May 2;208(4443):464–472. doi: 10.1126/science.7367873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenker M. B., Kado N. Y., Hammond S. K., Samuels S. J., Woskie S. R., Smith T. J. Urinary mutagenic activity in workers exposed to diesel exhaust. Environ Res. 1992 Apr;57(2):133–148. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(05)80074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear R. C., Selvin S. OSHA's permissible exposure limits: regulatory compliance versus health risk. Risk Anal. 1989 Dec;9(4):579–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1989.tb01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan W. M., Hammond S. K. Impact of "designated smoking area" policy on nicotine vapor and particle concentrations in a modern office building. J Air Waste Manage Assoc. 1990 Jul;40(7):1012–1017. doi: 10.1080/10473289.1990.10466741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]