Abstract

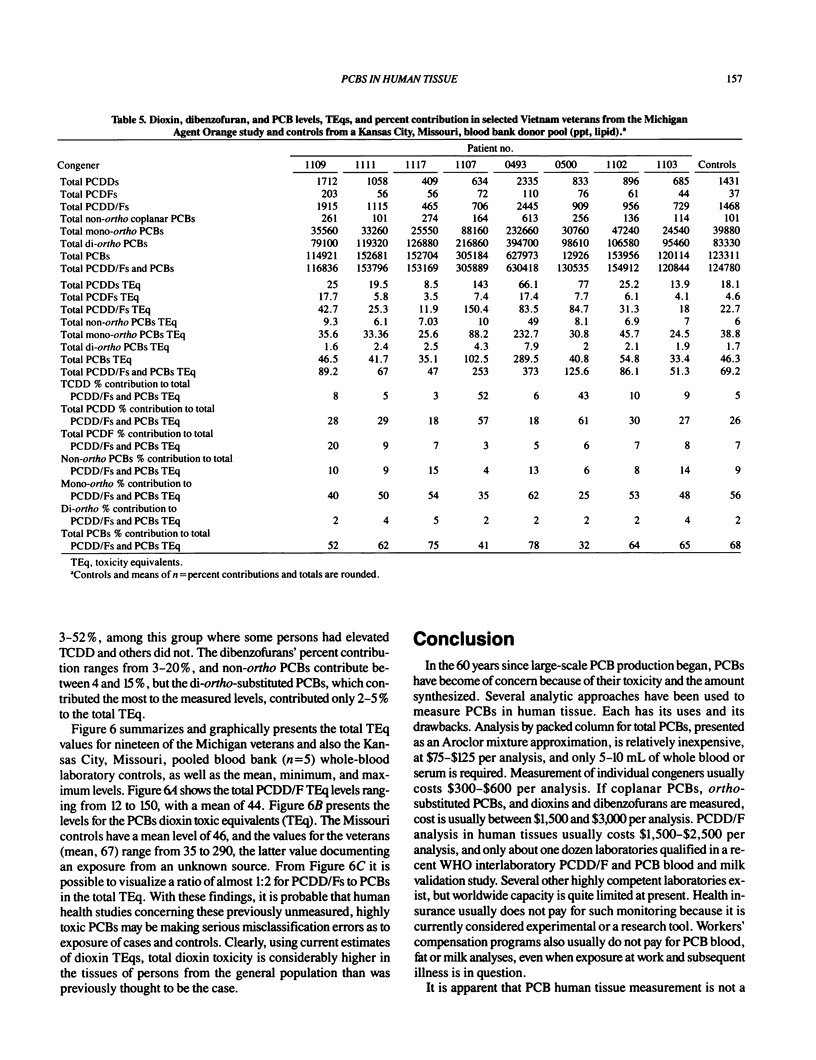

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are synthetic chemicals, manufactured in volume from about 1929 to the 1970s. Environmental contamination by PCBs has been documented in various substances, including human tissue. PCBs have been measured in human tissue by a variety of analytical methods. PCB levels have been reported as an approximation of total PCB content expressed in terms of a commercial mixture, by identification and quantification of chromatographic peaks, or by qualitative and quantitative characterization of specific congeners. Until recently, the coplanar mono-ortho- and di-ortho substituted PCBs, which are especially toxic and present in significant concentration in humans from industrial countries, had not been measured in human tissues. Examples of various types of commonly used analyses are presented in general population subjects and in persons who experienced special exposure. In this paper, the usefulness of PCB blood determinations following potential exposure is demonstrated, and their application in health studies is illustrated from a number of case studies. Coplanar PCB, mono-ortho-substituted and di-ortho-substituted PCB levels in human blood are presented and compared with polychlorinated dioxin (PCDD) and polychlorinated dibenzofuran (PCDF) levels in the U.S. population. Dioxin toxic equivalents for the two groups of chemicals are calculated and compared. It is found that mono-ortho-substituted and, to a lesser extent, coplanar PCBs, contribute substantially to dioxin toxic equivalents (TEq) in blood from U.S. adults. Because of substantial PCB contribution to dioxin toxic equivalents, total dioxinlike toxicity can only be determined if dioxins, dibenzofurans, and dioxinlike PCBs are measured.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 400 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Fein G. G., Jacobson J. L., Jacobson S. W., Schwartz P. M., Dowler J. K. Prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls: effects on birth size and gestational age. J Pediatr. 1984 Aug;105(2):315–320. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayabuchi H., Ikeda M., Yoshimura T., Masuda Y. Relationship between the consumption of toxic rice oil and the long-term concentration of polychlorinated biphenyls in the blood of yusho patients. Food Cosmet Toxicol. 1981 Feb;19(1):53–55. doi: 10.1016/0015-6264(81)90303-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson J. L., Jacobson S. W., Humphrey H. E. Effects of exposure to PCBs and related compounds on growth and activity in children. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1990 Jul-Aug;12(4):319–326. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(90)90050-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan N., Tanabe S., Tatsukawa R. Potentially hazardous residues of non-ortho chlorine substituted coplanar PCBs in human adipose tissue. Arch Environ Health. 1988 Jan-Feb;43(1):11–14. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1988.9934366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda Y., Kuroki H., Haraguchi K., Nagayama J. PCB and PCDF congeners in the blood and tissues of yusho and yu-cheng patients. Environ Health Perspect. 1985 Feb;59:53–58. doi: 10.1289/ehp.59-1568081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda Y., Yoshimura H. Polychlorinated biphenyls and dibenzofurans in patients with yusho and their toxicological significance: a review. Am J Ind Med. 1984;5(1-2):31–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips D. L., Smith A. B., Burse V. W., Steele G. K., Needham L. L., Hannon W. H. Half-life of polychlorinated biphenyls in occupationally exposed workers. Arch Environ Health. 1989 Nov-Dec;44(6):351–354. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1989.9935905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogan W. J., Gladen B. C., Hung K. L., Koong S. L., Shih L. Y., Taylor J. S., Wu Y. C., Yang D., Ragan N. B., Hsu C. C. Congenital poisoning by polychlorinated biphenyls and their contaminants in Taiwan. Science. 1988 Jul 15;241(4863):334–336. doi: 10.1126/science.3133768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safe S. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs), dibenzofurans (PCDFs), and related compounds: environmental and mechanistic considerations which support the development of toxic equivalency factors (TEFs). Crit Rev Toxicol. 1990;21(1):51–88. doi: 10.3109/10408449009089873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe S., Kannan N., Subramanian A., Watanabe S., Tatsukawa R. Highly toxic coplanar PCBs: occurrence, source, persistency and toxic implications to wildlife and humans. Environ Pollut. 1987;47(2):147–163. doi: 10.1016/0269-7491(87)90044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff M. S., Schecter A. Accidental exposure of children to polychlorinated biphenyls. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1991 May;20(4):449–453. doi: 10.1007/BF01065832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]