Abstract

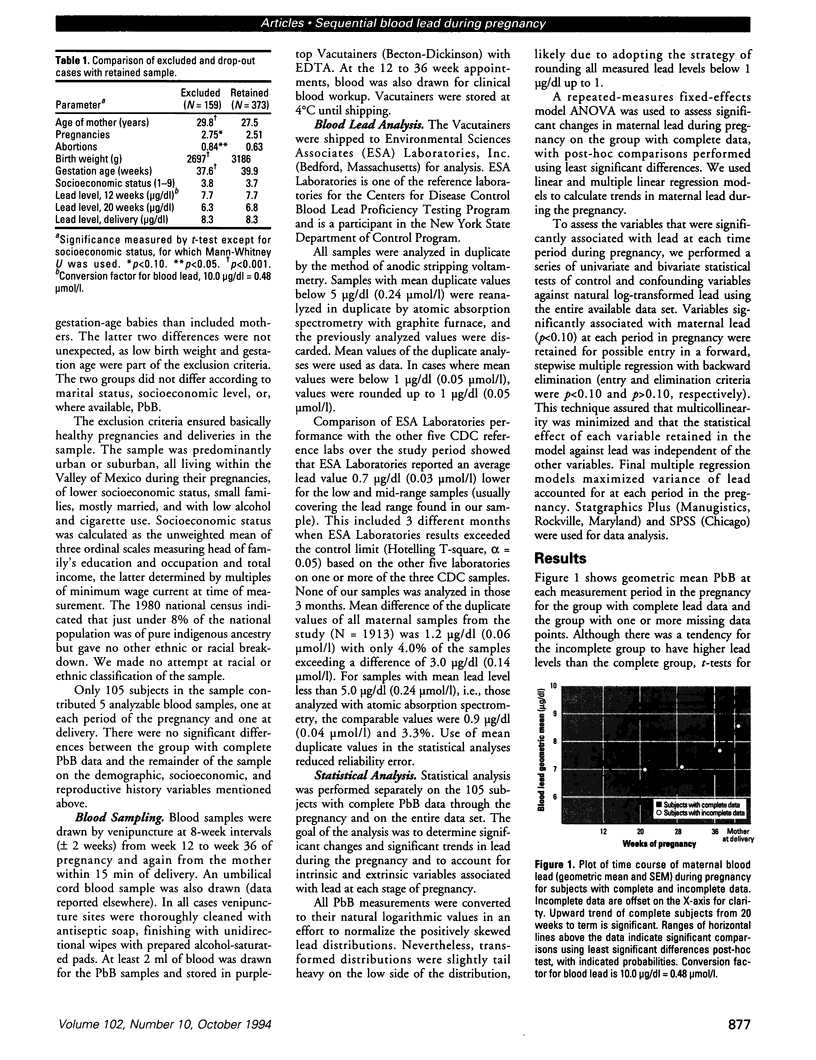

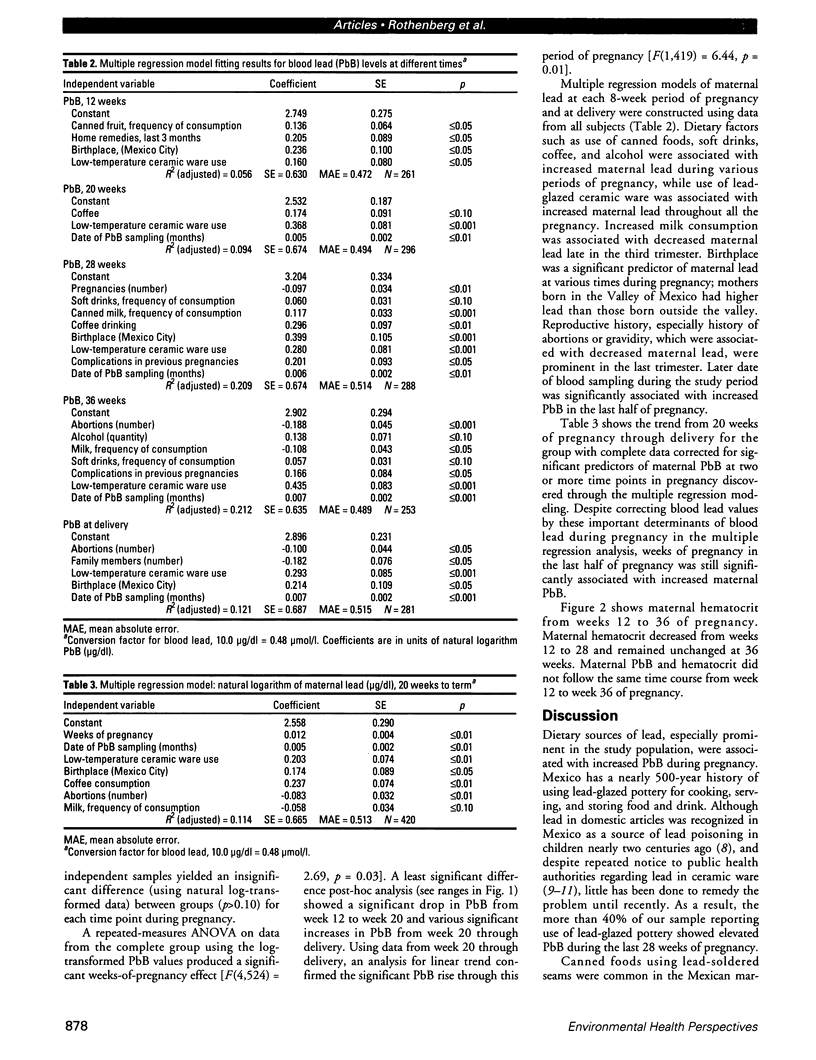

The first step in modeling lead kinetics during pregnancy includes a description of sequential maternal blood lead (PbB) during pregnancy and the factors controlling it. We analyzed PbB of 105 women living in the Valley of Mexico from week 12 to week 36 of pregnancy and again at parturition. We also used data from all women contributing blood at any stage of pregnancy to determine antecedents of PbB. Pregnancies were uneventful, and offspring were normal. Although geometric mean PbB level averaged around 7.0 micrograms/dl (0.34 mumol/l), with a range of 1.0-35.5 micrograms/dl throughout pregnancy, analysis of variance revealed a significant decrease in mean PbB from week 12 to week 20 (1.1 micrograms/dl) and various significant increases in mean PbB from week 20 to parturition (1.6 micrograms/dl). Regression analyses confirmed the positive linear PbB trend from 20 weeks to parturition and additional contributions of dietary calcium, reproductive history, lifetime residence of Mexico City, coffee drinking, and use of indigenous lead-glazed pottery. Although decreasing hematocrit has been suggested to explain first-half pregnancy PbB decrease, the time course of hematocrit decrease in the present study did not match the sequential changes in PbB. While hemodilution and organ growth in the first half of pregnancy may account for much of the PbB decrease seen between 12 and 20 weeks, the remaining hemodilution and accelerated organ growth of the last half of pregnancy do not predict the trend toward increasing maternal PbB concentration from 20 weeks to delivery. Mobilization of bone lead, increased gut absorption, and increased retention of lead may explain part of the upward PbB trend in the second half of pregnancy. Reduction of lifetime lead exposure may be required to decrease risk of fetal exposure.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alexander F. W., Delves H. T. Blood lead levels during pregnancy. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1981;48(1):35–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00405929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman E. A., Massey L. K., Wise K. J., Sherrard D. J. Effects of dietary caffeine on renal handling of minerals in adult women. Life Sci. 1990;47(6):557–564. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90616-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonithon-Kopp C., Huel G., Grasmick C., Sarmini H., Moreau T. Effects of pregnancy on the inter-individual variations in blood levels of lead, cadmium and mercury. Biol Res Pregnancy Perinatol. 1986;7(1):37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchet J. P., Roels H., Hubermont G., Lauwerys R. Placental transfer of lead, mercury, cadmium, and carbon monoxide in women. II. influence of some epidemiological factors on the frequency distributions of the biological indices in maternal and umbilical cord blood. Environ Res. 1978 Jun;15(3):494–503. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(78)90128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullmer C. S. Intestinal interactions of lead and calcium. Neurotoxicology. 1992 Winter;13(4):799–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garel J. M. Hormonal control of calcium metabolism during the reproductive cycle in mammals. Physiol Rev. 1987 Jan;67(1):1–66. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1987.67.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershanik J. J., Brooks G. G., Little J. A. Blood lead values in pregnant women and their offspring. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1974 Jun 15;119(4):508–511. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(74)90210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaney R. P., Recker R. R. Effects of nitrogen, phosphorus, and caffeine on calcium balance in women. J Lab Clin Med. 1982 Jan;99(1):46–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez Avila M., Romieu I., Rios C., Rivero A., Palazuelos E. Lead-glazed ceramics as major determinants of blood lead levels in Mexican women. Environ Health Perspect. 1991 Aug;94:117–120. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94-1567967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hytten F. Blood volume changes in normal pregnancy. Clin Haematol. 1985 Oct;14(3):601–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Cohen W. R., Epstein F. H. Vitamin D and calcium hormones in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1980 May 15;302(20):1143–1145. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198005153022010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahaffey K. R. Biokinetics of lead during pregnancy. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1991 Jan;16(1):15–16. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(91)90127-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer-Popken O., Denkhaus W., Konietzko H. Lead content of fetal tissues after maternal intoxication. Arch Toxicol. 1986 Feb;58(3):203–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00340983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson U., Attewell R., Christoffersson J. O., Schütz A., Ahlgren L., Skerfving S., Mattsson S. Kinetics of lead in bone and blood after end of occupational exposure. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1991 Jun;68(6):477–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1991.tb01273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkin R. M. Calcium metabolism in pregnancy: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975 Mar 1;121(5):724–737. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(75)90481-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pounds J. G., Long G. J., Rosen J. F. Cellular and molecular toxicity of lead in bone. Environ Health Perspect. 1991 Feb;91:17–32. doi: 10.1289/ehp.919117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz M. B., Wetherill G. W., Kopple J. D. Kinetic analysis of lead metabolism in healthy humans. J Clin Invest. 1976 Aug;58(2):260–270. doi: 10.1172/JCI108467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg S. J., Pérez Guerrero I. A., Perroni Hernández E., Schnaas Arrieta L., Cansino Ortiz S., Suro Cárcamo D., Flores Ortega J., Karchmer S. Fuentes de plomo en embarazadas de la Cuenca de México. Salud Publica Mex. 1990 Nov-Dec;32(6):632–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg S. J., Schnaas-Arrieta L., Pérez-Guerrero I. A., Hernández-Cervantes R., Martínez-Medina S., Perroni-Hernández E. Factores relacionados con el nivel de plomo en sangre en niños de 6 a 30 meses de edad en el Estudio Prospectivo de Plomo en la Ciudad de México. Salud Publica Mex. 1993 Nov-Dec;35(6):592–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg S. J., Schnaas-Arrieta L., Ugartechea J. C., Perroni-Hernandez E., Perez-Guerrero I. A., Cansino-Prtiz S., Salinas V., Zea-Prado F., Chicz-Demet A. A documented case of perinatal lead poisoning. Am J Public Health. 1992 Apr;82(4):613–614. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.4.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu J. E., Ziegler E. E., Fomon S. J. Maternal lead exposure and blood lead concentration in infancy. J Pediatr. 1978 Sep;93(3):476–478. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)81169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbergeld E. K. Lead in bone: implications for toxicology during pregnancy and lactation. Environ Health Perspect. 1991 Feb;91:63–70. doi: 10.1289/ehp.919163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbergeld E. K., Sauk J., Somerman M., Todd A., McNeill F., Fowler B., Fontaine A., van Buren J. Lead in bone: storage site, exposure source, and target organ. Neurotoxicology. 1993 Summer-Fall;14(2-3):225–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbergeld E. K., Schwartz J., Mahaffey K. Lead and osteoporosis: mobilization of lead from bone in postmenopausal women. Environ Res. 1988 Oct;47(1):79–94. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(88)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueland K., Metcalfe J. Circulatory changes in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1975 Sep;18(3):41–50. doi: 10.1097/00003081-197509000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]