Abstract

tRNA(m1G37)methyltransferase (TrmD) catalyzes the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosyl-l- methionine (AdoMet) to G37 within a subset of bacterial tRNA species, which have a G residue at the 36th position. The modified guanosine is adjacent to and 3′ of the anticodon and is essential for the maintenance of the correct reading frame during translation. Here we report four crystal structures of TrmD from Haemophilus influenzae, as binary complexes with either AdoMet or S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine (AdoHcy), as a ternary complex with AdoHcy and phosphate, and as an apo form. This first structure of TrmD indicates that it functions as a dimer. It also suggests the binding mode of G36G37 in the active site of TrmD and the catalytic mechanism. The N-terminal domain has a trefoil knot, in which AdoMet or AdoHcy is bound in a novel, bent conformation. The C-terminal domain shows structural similarity to trp repressor. We propose a plausible model for the TrmD2–tRNA2 complex, which provides insights into recognition of the general tRNA structure by TrmD.

Keywords: methyltransferase/SPOUT class/trmD/tRNA(m1G37)methyltransferase/tRNA modification

Introduction

Compared with missense errors, most of which are not harmful to proteins, almost all of the frameshift errors in translation are detrimental to the synthesis of a functional protein, since they result in a truncated, usually unstable or inactive, peptide. The evolution of translational reading frame maintenance must have been an early event, and it has been shown that several structurally different modified nucleosides present in different tRNAs and at different positions of the tRNA have a common function: they all improve reading frame maintenance (Urbonavièius et al., 2001). Many of the modified nucleosides in tRNA are present in the anticodon region, especially at position 34 (the wobble position) and 37 (3′ and adjacent to the anticodon). One of them is 1-methylguanosine (m1G37), which is present at position 37 in tRNAs specific for leucine (CUN codons, N being any of the four major nucleosides), proline (CCN) and one of the arginine tRNAs (CGG) from all three domains of life Archaea, Bacteria and Eukarya (Björk, 1998; Björk et al., 2001). In Escherichia coli, ∼1.0% of the genome is devoted to encoding >40 tRNA modification enzymes (Holmes et al., 1995). One of them is tRNA(m1G37)methyltransferase (TrmD), which catalyzes the transfer of a methyl group from its cofactor S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet) specifically to guanosine at position 37 within seven of the 46 tRNA species in E.coli. One specific function of m1G37 is to prevent frameshifting and thereby maintain the correct reading frame during translation (Björk et al., 1989).

The genes encoding TrmD have been identified from all three domains of life, and it has been suggested that they originated from a common primordial gene. It appears that TrmD is part of the minimal set of gene products required for life (Björk et al., 2001). The deficiency of m1G37 induces strong pleiotropic effects such as reduction in growth rate and polypeptide chain elongation rate in vivo (Li and Björk, 1995; Persson et al., 1995). The G residue of the anticodon at position 36 is crucial for optimal activity of TrmD, and the dinucleotide GpG and the polynucleotide poly(G) were shown to be both potent and specific inhibitors of the enzyme (Holmes et al., 1995). However, it appears that TrmD recognizes the general tRNA structure and binds to tRNA even in the absence of the GpG structural motif (Qian and Björk, 1997). The GpG sequence may be involved in stabilizing the enzyme– tRNA complex by binding to the active site of the enzyme. It was demonstrated that AdoMet is not required for tRNA binding (Holmes et al., 1995).

TrmD and SpoU methyltransferase (MTase) families previously were considered to be unrelated to each other, but it has been proposed that they might share a common evolutionary origin and form a single ‘SPOUT’ (SpoU-TrmD) class (Anantharaman et al., 2002). A common fold of the ‘SPOUT’ class has been predicted to be distinct from the ‘consensus MTase fold’. This prediction has been partly confirmed by recent crystal structures of two apparent members of the SpoU family: RmlB 23S rRNA MTase from E.coli [Protein Data Bank (PDB) entry 1GZ0; Michel et al., 2002] and a hypothetical protein RrmA from Thermus thermophilus (PDB entry 1IPA; Nureki et al., 2002). These proteins have a deep trefoil knot structure in the C-terminal catalytic domain. Threading the polypeptide chain through an untwisted loop gives a trefoil knot; in a shallow trefoil knot, only a few (at most 15) residues at one end of the chain are tucked through the loop and such a knot can disappear if the structure is viewed from a different angle, whereas in the deep trefoil knot many more residues are tucked through the loop (Taylor, 2000; Nureki et al., 2002).

Despite the crucial role of m1G37 of tRNA in reading frame maintenance, no structural information is available on TrmD. In order to provide the missing structural information and to understand better the mode of recognition of tRNA by TrmD, we have determined four crystal structures of TrmD from Haemophilus influenzae, a 246 residue protein (Mr = 27 542 Da) that shows a high level of amino acid sequence identity (83%) to E.coli TrmD. They represent the first structure of any tRNA MTase including the TrmD family. The active site cleft is formed at the dimer interface, which strongly suggests that the functional unit of TrmD is a dimer. It also reveals that the N-terminal domain (NTD) of TrmD is structurally similar to the C-terminal domain (CTD) or main domain of SpoU family members, as predicted recently (Anantharaman et al., 2002). Our TrmD structures show that a deep trefoil knot in the NTD domain provides the L-shaped pocket for binding AdoMet or S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine (AdoHcy), and the bound cofactors adopt a novel bent conformation. The CTD of TrmD shows structural similarity to DNA-binding domains of trp and tet repressors. We also propose a model for the TrmD2–tRNA2 complex, which provides insights into how TrmD recognizes the general structural features of tRNA.

Results and discussion

Structure determination

The crystal structure of H.influenzae TrmD in the apo form was determined at 2.80 Å resolution using the multiwavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD) data collected from a crystal of the selenomethionine (SeMet)-substituted enzyme and refined to 1.85 Å resolution (Table I). Subsequently, the structures of binary complexes with either AdoMet or AdoHcy were determined using the molecular replacement method at 2.05 and 1.80 Å, respectively. The crystals used for determining these structures were grown under sodium acetate conditions (Kim et al., 2003). The model consists of residues –7 to 160 and 174 to 246 for the apo form, and –1 to 160 and 170 to 250 for the binary complex with AdoMet (or AdoHcy). Residue numbers <1 or >246 refer to extra residues of a 20 residue N-terminal tag or an eight residue C-terminal tag that were introduced into the recombinant protein. Later, we solved the structure of a ternary complex with AdoHcy and phosphate using a crystal grown under ammonium phosphate conditions. The ternary complex model consists of residues –1 to 163 and 166 to 250. A strong electron density observed in the active site was interpreted as a phosphate ion, reflecting the presence of phosphate ions at high (∼1.0 M) concentration in the crystallization medium. We speculate that this phosphate ion bound in the active site may mimic the phosphate on the 5′ side of G37 of the cognate tRNA.

Table I. Statistics on X-ray data collection and model refinement.

| Data set | Se MAD (apo form) | Apo form | +AdoMet | +AdoHcy | +AdoHcy and PO43– | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9798 | 0.9795 | 0.9500 | 0.9500 | 0.9500 | 0.9500 | 1.5418 |

| Resolution (Å) | 20.0–2.8 | 20.0–2.8 | 20.0–2.8 | 20.0–1.85 | 20.0–2.05 | 20.0–1.80 | 20.0–2.20 |

| Total reflections | 81 196 | 81 704 | 81 294 | 216 789 | 114 230 | 167 465 | 39 786 |

| Unique reflections | 8457 | 8450 | 8450 | 28 115 | 18 936 | 28 092 | 15 004 |

| Completenessa (%) | 99.8 (100) | 99.7 (100) | 99.7 (100) | 99.8 (99.8) | 99.3 (99.3) | 99.9 (99.9) | 98.5 (91.6) |

| I/σI | 7.7 (2.9) | 7.0 (2.3) | 7.4 (2.7) | 9.3 (2.2) | 6.0 (2.3) | 6.5 (2.0) | 7.4 (2.3) |

| Rmergeb (%) | 8.1 (26.0) | 9.0 (31.0) | 8.3 (27.9) | 6.0 (35.3) | 10.5 (32.1) | 7.5 (37.2) | 6.9 (26.2) |

|

Model refinement | |||||||

| Rwork/Rfreec (%) | 19.4/21.9 | 17.6/21.6 | 18.4/21.5 | 22.0/26.4 | |||

| (23.5/25.0) | (17.6/22.2) | (24.5/26.1) | (26.7/30.3) | ||||

| Reflections in working set/test set | 25 327/2788 | 17 071/1865 | 25 305/2787 | 13 478/1526 | |||

| Cross-validated σA coordinate error (Å) | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.29 | |||

| R.m.s. deviation in bond lengths (Å)/angles (°) | 0.005/1.1 | 0.005/1.2 | 0.005/1.2 | 0.006/1.2 | |||

| No. of non-hydrogen atoms/average B-factor (Å2) | |||||||

| Protein | 1899/24.2 | 1925/19.7 | 1925/22.0 | 1978/30.9 | |||

| Cofactor (AdoMet or AdoHcy) | – | 27/18.2 | 26/19.2 | 26/23.6 | |||

| Phosphate ion | – | – | – | 5/75.3 | |||

| Water | 262/36.9 | 240/34.0 | 278/36.4 | 103/36.0 | |||

aValues in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

bRmerge = ΣhΣi|I(h)i – <I(h)>|/ΣhΣiI(h)i

cR = Σ||Fobs| – |Fcalc||/Σ|Fobs| (Brünger, 1992).

Overall structure of TrmD subunit

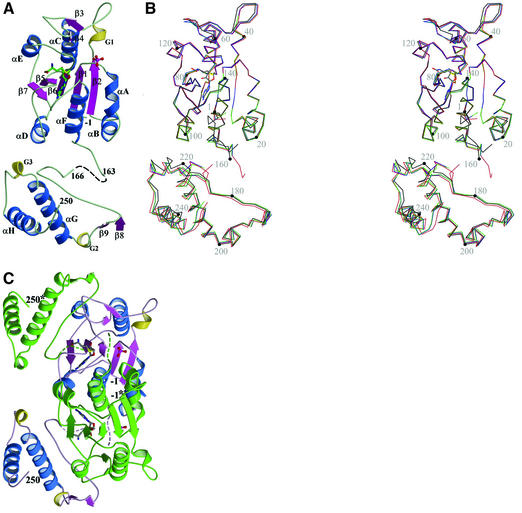

TrmD comprises two distinct domains, a larger NTD of α/β-fold (residues 1–156) and a smaller CTD (residues 176–246) (Figure 1). An extended flexible linker (residues 157–175) connects these two domains, which do not contact each other in a monomer. The inter-domain linker is largely disordered in the apo structure, with 13 residues (161–173) being invisible. However, it is more ordered in the binary complexes with either AdoMet or AdoHcy, with nine residues (161–169) being invisible. In the ternary complex, only two residues (164 and 165) are disordered. This flexible loop appears to play an important role as a possible lid to cover the active site upon binding G36G37 of the cognate tRNA and in providing a likely candidate for the catalytic base, Asp169 (discussed further below).

Fig. 1. Overall fold of a TrmD monomer. (A) Ribbon diagram (ternary complex). Two missing residues (164 and 165) in the flexible inter-domain linker are shown as dashed lines. G1–G3 represent 310-helices. AdoHcy is shown in a stick model and the phosphate ion in a ball-and-stick model. Carbon atoms are colored in green, oxygen in red, nitrogen in blue, phosphorus in purple, and sulfur in yellow. (B) Stereo view of Cα traces of four models of TrmD. Black is for the apo structure, green for the AdoMet binary complex, blue for the AdoHcy binary complex, and red for the ternary complex with AdoHcy and phosphate. Four models are superimposed in the central five-stranded β-sheet in the NTD. A black dot is marked on every 20th Cα atoms of the apo structure. A comparison of the apo structure and three complex structures shows relatively large r.m.s. differences of 0.66–0.67 Å. The two binary complex structures show the smallest r.m.s. difference of 0.16 Å. R.m.s. differences between binary complex structures and the ternary complex structure are in the intermediate range of 0.39–0.40 Å. (C) Ribbon diagram of a TrmD dimer (ternary complex). One protomer is colored using the same scheme as in (A) and the other protomer is in green. The dashed lines represent the inter-domain linker, which is more ordered in the ternary complex than in binary complexes. Carbon atoms are colored in gray, and other atoms are colored using the same scheme as in (A). This view is obtained by a clockwise rotation of the TrmD monomer in (A) by ∼30° around an axis that is normal to the plane of the figure.

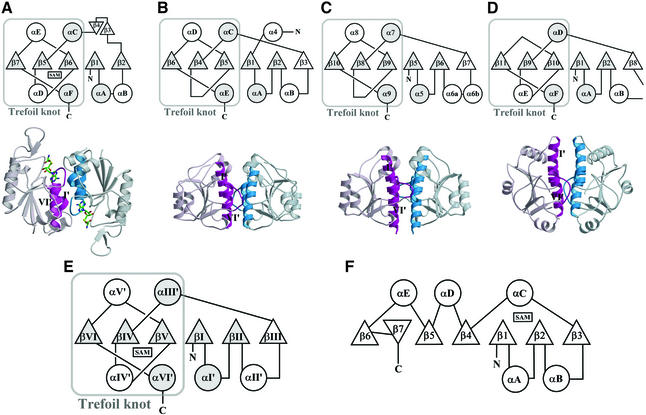

The N-terminal α/β domain consists of a parallel five-stranded β-sheet (β7–β5–β6–β1–β2), which is flanked by two helices (αC and αE) on one side and by four helices (αA, αB, αD and αF) on the other side. A β-hairpin (β3–loop–β4) is located between β2 and αC. The fold of the NTD is distinct from the previously defined ‘consensus MTase fold’ (Figure 2; Schluckebier et al., 1995). The parallel β-sheet in the NTD follows a (7↑5↑6↑1↑2↑) topology, whereas the consensus MTase fold follows a (6↑7↓5↑4↑1↑2↑3↑) topology. The consensus MTase fold contains two additional antiparallel β-strands (6↑7↓), and its remaining five parallel strands have a different topology from that of TrmD NTD. Another significant difference is the presence of an unusual trefoil knot structure in the TrmD NTD constituted by β5–β7 and αD–αF (Figure 2A). The knot structure provides the binding site for the cofactor, as discussed further below. The smaller CTD domain, which appears to play an important role in tRNA recognition, consists mainly of two perpendicularly packed helices (αG and αH). Additionally, there are a β-hairpin (β8–loop–β9) and two 310-helices (G2 and G3). A DALI search (Holm and Sander, 1993) indicated structural similarity between TrmD CTD and trp repressor (Otwinowski et al., 1988). The two helices αG and αH of the TrmD CTD are strikingly well superimposed onto the equivalent helices in trp repressor, with an r.m.s. difference of 1.4 Å between 32 Cα atoms.

Fig. 2. ‘SPOUT class MTase fold’ versus ‘consensus MTase fold’. (A–D) Figures in (A) are for TrmD from H.influenzae, (B) for RmlB from E.coli (PDB entry 1GZ0), (C) for RrmA from T.thermophilus (PDB entry 1IPA), and (D) for MT0001 from M.thermoautotrophicum (PDB entry 1K3R). Figures in the first row are topology diagrams for the ‘SPOUT domain’ of each protein. Common α-helices and β-strands are denoted by circles or triangles filled with gray color. Figures in the second row show the dimer interface between the two ‘SPOUT domains’, each of which comes from different subunits. One monomer is colored in light scarlet and the other in light blue. The two α-helices (αI′ and αVI′) and part of the loop βVI/aVI′ are highlighted in deep colors, and the two α-helices are indicated by Roman numbers, whose definitions are as in (E). (E) Topology diagram of the ‘SPOUT class MTase fold’, as defined in this study. The secondary structure elements that are common to the four SPOUT class MTases are shaded. (F) Topology diagram of the previously defined ‘consensus MTase fold’.

A pair-wise superposition of the four structures determined in this study gives r.m.s. differences in the range of 0.16–0.67 Å for Cα atoms of residues 1–160 and 174–246. The structural differences mainly originate from the movement of the CTD, in particular two helices αG and αH (Figure 1B). R.m.s. differences of Cα atoms in the NTD are 0.10–0.41 Å, while those in the CTD are 0.25–1.31 Å. A β-hairpin (β3–loop–β4) region in the NTD shows a relatively large r.m.s. difference of 0.17–0.66 Å for 13 Cα atoms. The region around helices αG and αH (residues 215–246) shows a large Cα r.m.s. difference of ∼1.5 Å between the binary (or ternary) complex structures and the apo structure. The conformational variability of CTD and the β-hairpin (β3–loop–β4) region in the NTD seems to be related to their role in tRNA binding.

SPOUT class MTase fold of the N-terminal domain

The TrmD NTD possesses a similar fold to the CTD of RmlB and RrmA (Figure 2). The central β-sheet of RmlB or RrmA consists of six parallel strands (β6–β4–β5– β1–β2–β3 in RmlB; β10–β8–β9–β5–β6–β7 in RrmA) and five of them are arranged in the same order (β6–β4–β5– β1–β2 in RmlB; β10–β8–β9–β5–β6 in RrmA) as TrmD (β7–β5–β6–β1–β2). The common five strands are well superimposed spatially (mean r.m.s. differences of 1.0– 1.2 Å between 28 Cα atoms). Furthermore, four helices (αA, αC, αD and αE in RmlB; α5, α7, α8 and α9 in RrmA) are structural equivalents of αA, αC, αE and αF in TrmD (Figure 2A–C). A DALI (Holm and Sander, 1993) structural similarity search with the TrmD NTD revealed another similar structure: a conserved hypothetical protein MT0001 from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (PDB entry 1K3R; Zarembinski et al., 2003) with a z-score of 7.4. It comprises two distinct domains: a main domain (residues 1–67 and 161–263) and an intervening subsidiary domain (residues 68–160). The main domain displays a fold similar to the TrmD NTD and also has a trefoil knot (Figure 2D). The main domain has a central β-sheet of six parallel strands (β11–β9–β10–β1–β2–β8), five of which (β11–β9–β10–β1–β2) are arranged in the same order and are well superimposed with the central five strands of the TrmD NTD (β7–β5–β6–β1–β2) (an r.m.s. difference of 1.6 Å between 28 Cα atoms). This structural similarity suggests that the conserved hypothetical MT001 may function as an AdoMet-dependent MTase and may be categorized into an extended ‘SPOUT’ class MTase.

On the basis of common features among the present TrmD structure and three other currently available structures of apparent SPOUT class members, we are tempted to define a ‘SPOUT class MTase fold’ (Figure 2E). It is distinct from the ‘consensus MTase fold’ (Figure 2F). A significant feature of this ‘SPOUT class MTase fold’ is the presence of a deep trefoil knot. Our structures of TrmD in complex with either AdoMet or AdoHcy clearly establish that the deep trefoil knot provides the cofactor-binding site. We refer to the domain possessing the ‘SPOUT class MTase fold’ as the ‘SPOUT domain’. Another common characteristic of the SPOUT class MTases may be dimer formation. The two helices αI′ and αVI′, and the C-terminal part of the loop βVI/αVI′ are involved in dimerization (Figure 2A–D). It is worth mentioning, however, that dimerization patterns are different; TrmD forms a dimer in an antiparallel fashion, whereas RmlB, RrmA and MT0001 form a dimer in a parallel fashion.

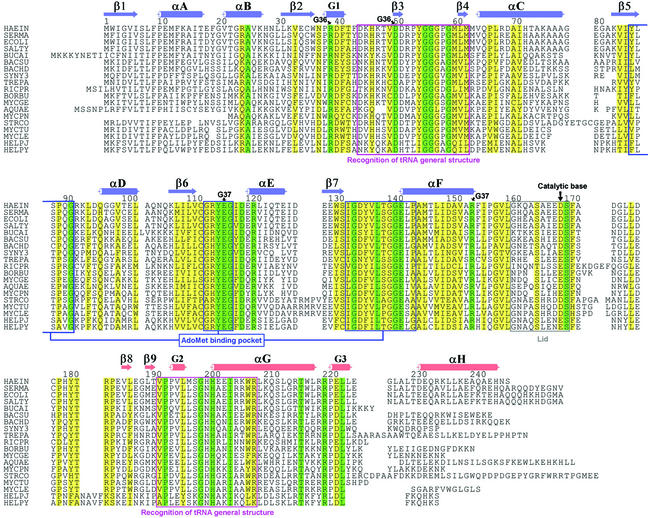

TrmD functions as a dimer

Our structures suggest that the functional unit of TrmD is a dimer, which is generated by crystallographic 2-fold symmetry (Figure 1C). The buried surface area in the dimer interface for the ternary complex is ∼3900 Å2, which is 26% of the total surface area per monomer (15 100 Å2). It is divided into ∼1200 Å2 for a single interface between two NTDs, ∼2200 Å2 for two interfaces between the NTD and CTD, and ∼500 Å2 for two interfaces between the inter-domain linker and the NTD. The two helices αA and αF, and the C-terminal part of the loop β7/αF are involved mainly in the interaction between two NTDs. The inter-domain linker is located in the very vicinity of AdoMet/AdoHcy bound in the NTD of the other protomer. The loop region of residues 179–183 in the CTD of one protomer is sandwiched between the loop β3/β4 and the N-terminal side of αE in the NTD of the other protomer. A total of 25 residues are strictly conserved among 19 TrmD sequences (Figure 3). Among them, 13 residues are located in the dimer interface, and seven of these 13 residues (Gly55, Gly56, Asp119, Arg121, Ser170, Ile204 and Arg220 in H.influenzae TrmD) are directly involved in the dimer interaction through hydrophobic contacts, hydrogen bonds and salt bridges. In particular, highly conserved residues Ser170* and Asp177* directly interact with AdoMet or AdoHcy through hydrogen bonding (Figure 4A–C). An asterisk after the residue number denotes that the residue comes from the other protomer in a dimer. This observation argues that dimerization is a conserved feature among TrmD family members and it possibly could be crucial for its function.

Fig. 3. Alignment of 19 TrmD amino acid sequences. Secondary structural elements in the NTD of H.influenzae TrmD are colored in blue, and those in the CTD are colored in red. Strictly conserved residues and highly conserved residues are boxed in green and yellow colors, respectively. The residue numbers are for TrmD from H.influenzae. HAEIN is for TrmD from H.influenzae (SWISS-PROT entry P43912), SERMA for Serratia marcescens (P36244), ECOLI for E.coli (P07020), SALTY for Salmonella typhimurium (P36245), BUCAI for Buchnera aphidicola (P57476), BACSU for Bacillus subtilis (O31741), BACHD for Bacillus halodurans (Q9KA15), SYNY3 for Synechocystis sp. (P72828), TREPA for Treponema pallidum (O83878), RICPR for Rickettsia prowazekii (Q9ZE37), BORBU for Borrelia burgdorferi (O51641), MYCGE for Mycoplasma genitalium (P47683), AQUAE for Aquifex aeolicus (O67463), MYCPN for Mycoplasma pneumoniae (P75132), STRCO for Streptomyces coelicolor (O69882), MYCTU for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Q10797), MYCLE for Mycobacterium leprae (O33017), HELPJ for Helicobacter pylori J99 (Q9ZK66), and HELPY for Helicobacter pylori 26695 (O25766).

Fig. 4. AdoMet/AdoHcy binding mode. (A–C) Stereo diagrams of AdoMet in the binary complex and AdoHcy in binary and ternary complexes, respectively. AdoMet/AdoHcy is shown in stick models and colored using the same scheme as in Figure 1A. The residues interacting with AdoMet/AdoHcy are also shown in stick models and their carbon atoms are colored in gray. Water molecules are shown as red balls. Dotted lines represent possible hydrogen bonds between AdoMet/AdoHcy and TrmD or water molecules. The loops colored in yellow are from one protomer and that in purple is from the other protomer. An asterisk after the residue number denotes that the residue comes from the other protomer. In (C), G113 (labeled in red) supports the twist conformation of the ribose ring of AdoHcy through a hydrogen bond, indicated by a red, dotted line. (D) σA-weighted simulated annealing omit map for the binary complex around AdoHcy, contoured at 1.0σ. (E) A novel, bent conformation of AdoMet bound in TrmD (thick lines in green). AdoMet and AdoHcy observed in various MTases are superimposed in the ribose ring. A thin stick model colored in blue represents another distinct bent conformation of AdoHcy in CbiF (PDB entry 1CBF). Extended conformations that are observed most frequently are drawn in thin stick models: AdoMet bound in VP39 (1VPT), ErmC′ (1QAO), FtsJ (1EIZ), M.TaqI (2ADM), M.HhaI (1HMY), PIMT (1JG4) and COMT (1VID) are colored in brown, yellow, red, cyan, black, pink and gray, respectively. AdoHcy bound in CheR (1AF7) is in violet. (F) Superposition of AdoMet and AdoHcy observed in three TrmD complex structures. They are superimposed in the adenine part. Oxygen atoms are colored in red, nitrogen in blue and sulfur in yellow. Carbon atoms in AdoMet are colored in green, those in AdoHcy of the binary complex in light pink, and those in AdoHcy of the ternary complex in gray.

Another important observation is that the active site is located at the subunit interface. Both chains of the dimer participate in forming the active site cleft, into which the target residue of methylation (i.e. G37) in a cognate tRNA may fit. One protomer contributes part of the loop β6/αE (residues Arg114–Glu116) and 310-helix G3 (residues Arg39–Asp40). The other protomer contributes helix αB (Phe19*–Lys27*), part of helix αF and the C-terminal side loop (Arg154*–Leu160*) of helix αF. The region consisting of residues Gly161*–Asp169* (dashed lines in Figure 1C) plays a role as a lid for covering the active site cleft. This region, which is disordered in the apo structure as well as the structures of binary complexes with either AdoMet or AdoHcy, becomes largely ordered in the structure of the ternary complex with AdoHcy and phosphate. Structural features of the active site strongly imply that Asp169* and Arg154* may participate in recognition of G37 of the cognate tRNA. Furthermore, Asp169* appears to be a likely candidate for the catalytic base. These observations indicate that TrmD functions as a dimer.

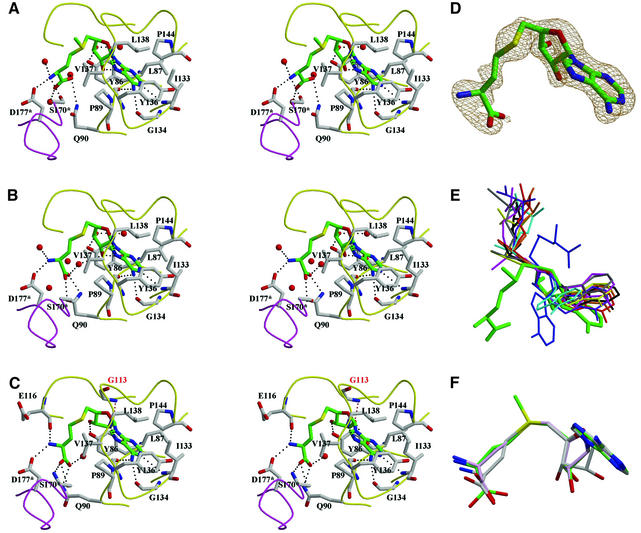

Cofactor is bound in a novel bent conformation

The cofactor-binding pocket of TrmD is located at the trefoil knot structure in its NTD and is L-shaped. The adenine moiety of AdoMet is bound deep in one part of the pocket and the amino acid is partially buried in the other part of the pocket. The positively charged methyl group of AdoMet protrudes from the hinge region of the L-shaped pocket. The cofactor-binding pocket consists of three regions: residues 86–91 (the C-terminal part of β5 and β5/αD loop), residues 113–117 (β6/αE loop) and residues 133–144 (β7/αF loop and the N-terminal part of αF) (Figures 3 and 4A–C). Only the second region was predicted to be the AdoMet-binding motif (Anantharaman et al., 2002). The AdoMet-binding pocket is lined with six highly conserved glycine residues at positions 91, 113, 117, 134, 140 and 141. The G140S mutation of TrmD from Salmonella typhimurium led to a reduced level (∼60% of the wild type) of the m1G population in bulk tRNA in vivo (Li and Björk, 1999). This might be due to a reduced catalytic activity caused by a perturbed structure of the AdoMet-binding pocket in the G140S mutant.

Binding of AdoMet in the binary complex involves an extensive network of hydrogen bonds as well as hydrophobic contacts. There are a total of nine hydrogen bonds between AdoMet and TrmD in the binary complex (Figure 4A). Four of them support adenine; the amide nitrogen of Ile133 makes a hydrogen bond with N1, the carbonyl oxygen atoms of Gly134 and Tyr136 with N6, and the amide nitrogen of Leu138 with N7. The same hydrogen-bonding pattern is observed for the binary and ternary complexes with AdoHcy. Two hydroxyl oxygen atoms of ribose (O2′ and O3′) form hydrogen bonds with the carbonyl oxygen of Leu87 and OH of Tyr86, respectively, in the AdoMet binary complex. This hydrogen-bonding pattern is conserved in the binary complex with AdoHcy but is slightly distorted in the ternary complex due to a different sugar conformation. The observed interaction with ribose is distinct from other MTases (M.HhaI, M.HaeIII, M.TaqI, COMT, VP39, CheR, etc.) and NADH-binding enzymes (Tanaka et al., 1996), where an acidic residue interacts with the two hydroxyl oxygen atoms of ribose. In the AdoMet binary complex, there are three hydrogen bonds between the methionine moiety and the residues Gln90, Ser170 and Asp177; Gln90 NE2 with one of the carboxylate oxygen atoms, and Ser170* OG and Asp177* OD2 with the amide nitrogen. This hydrogen-bonding pattern is altered considerably in the binary and ternary complexes with AdoHcy. Four water molecules are within hydrogen-bonding distance from two terminal carboxyl oxygen atoms, an amide nitrogen atom and one hydroxyl (O3′) of ribose of AdoMet in the AdoMet binary complex. In all three complexes of TrmD, there are two proline residues interacting with the adenine ring via hydrophobic contact. Pro89 makes a face-to-face van der Waals contact with the adenine ring on one side and Pro144 adopts a face-to-edge orientation on the other side. This is reminiscent of the case of M.HhaI, in which Phe18 and Trp41 residues interact with the adenine ring of AdoHcy in a similar manner (Klimasauskas et al., 1994). In addition to Pro89 and Pro144, Tyr86, Leu87, Ile133, Tyr136, Val137 and Leu138 also interact with the adenine moiety through hydrophobic contacts.

AdoMet and AdoHcy that are bound to the L-shaped cofactor-binding pocket in the binary and ternary complexes adopt a novel, bent conformation. In TrmD, the O4′–C4′–C5′–SD dihedral angle is –62° (for AdoMet) and –66°/–79° (for AdoHcy in binary/ternary complexes). In most of the AdoMet-dependent MTase structures (Martin and McMillan, 2002), AdoMet (or AdoHcy) has an extended conformation, with the O4′–C4′–C5′–SD dihedral angle in the range of –170 to –180° and 160 to 180°. The only exception is CbiF (cobalt-precorrin-4 methyltransferase), in which AdoHcy has a bent conformation with a dihedral angle of 82° (Schubert et al., 1998), with the homocysteine of AdoHcy being bent in the opposite direction, when compared with the amino acid moiety of AdoMet/AdoHcy bound in TrmD (Figure 4E).

Despite the similarity in the overall bent conformations of the bound AdoMet or AdoHcy in TrmD, we observe significant differences in the details of the cofactor conformations in the binary and ternary complexes, especially of ribose and methionine/homocysteine (Figure 4A–C and F). First, binding of a phosphate ion in the active site induces deformation of the ribose ring, concomitantly with the closure of the lid (Gly161*– Asp169*). In the binary complex with AdoMet or AdoHcy, the ribose ring adopts an approximate 2E conformation (the so-called C2′-endo form). However, in the ternary complex with AdoHcy and phosphate, it adopts an unusual twist form, i.e. 3T2 conformation. This twist conformation is directly maintained by a hydrogen bond between the exocyclic hydroxyl oxygen O2′ of ribose and the amide nitrogen N of the highly conserved Gly113 (distance 3.0 Å); this interaction is not observed for the 2E conformation of ribose in AdoMet or AdoHcy of the binary complexes. Secondly, the plane of the terminal carboxylate group of AdoHcy rotates by ∼75–90° as compared with that of AdoMet. The dihedral angle N–CA–C–O is 42° in AdoMet, but –48 and –33° in AdoHcy in the binary and ternary complexes, respectively. The rotation of the terminal carboxylate synchronizes with the movement of Ser170*, whose OG atom forms a hydrogen bond with the terminal amide in the case of AdoMet or the terminal carboxylate group in the case of AdoHcy. It should be noted that the strictly conserved Ser170* is disordered in the apo structure. Additionally, the conformational change in the amino acid moiety can be ascribed partly to the dihedral angle CG–CB–CA—N, which is –143° in the case of AdoMet and –96°/–44° in the case of AdoHcy in the binary/ternary complexes, respectively. To summarize, phosphate binding in the active site and concomitant lid closure induces a conformational change in the ribose moiety of the cofactor. The conformation of the amino acid moiety of the cofactor depends primarily on whether the reactive methyl group is present or not. The apo and binary complex structures determined in this study mimic the different states of the enzyme along the reaction pathway from the ligand-free state, to the AdoMet- and AdoHcy-bound state. The ternary complex with AdoHcy and phosphate may mimic the state after the methyl transfer, with products of both the cofactor and the substrate still bound to the active site, which is covered with the lid. The variable cofactor conformations may also reflect the different stages of the reaction catalyzed by TrmD.

Active site of TrmD and binding of G36G37

In the ternary complex with AdoHcy and phosphate, the bound phosphate ion lies between the guanidine groups of two highly conserved residues, Arg114 and Arg24*, in the vicinity of AdoHcy (Figures 1C and 5A). Whereas the loop region consisting of residues Gly161–Asp169 is disordered in the apo structure and the binary complex structures with AdoMet or AdoHcy, it is well defined by the electron density for most of the residues except Ala164 and Ser165 in the ternary complex. This loop region apparently acts as a lid to cover the active site cleft (Figures 1C and 5A), and the lid closure changes the active site from a cleft-shape into a pocket-shape. It should be noted that Asp169* in this loop region is likely to interact with G37 of the cognate tRNA and to act as a base in catalysis.

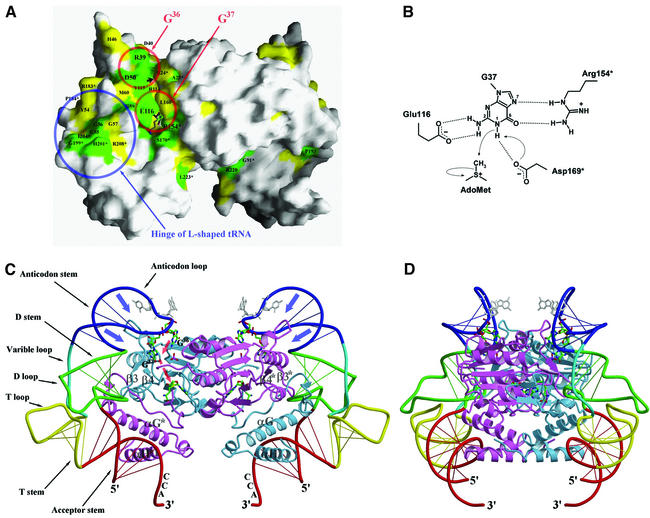

Fig. 5. (A) Molecular surface of a TrmD dimer (AdoMet binary complex), excluding a disordered loop covering the active site. Strictly conserved residues and highly conserved residues on the molecular surface are colored in green and yellow, respectively. Two red circles indicate the proposed binding sites for G36 and G37 of the cognate tRNA, respectively. A blue circle indicates the proposed binding site for the hinge region of the L-shaped tRNA. A small black arrow indicates the phosphate-binding position between R24* and R114 in the ternary complex. (B) Proposed catalytic mechanism of H.influenzae TrmD. (C) A proposed model of the TrmD2–tRNA2 complex in the same view as in (A). Each subunit of TrmD, in complex with AdoHcy and phosphate, is colored in blue and scarlet, respectively. AdoHcy is shown in a stick model and colored using the same scheme as in Figure 1A. G36 and G37 of tRNA are highlighted as thick stick models and colored using the same scheme as in Figure 1A. Two other bases of the anti codon are shown in gray stick models. (D) This view is obtained by a clockwise rotation of (C) by 90° around the vertical axis.

The sequence G36G37 is present in all tRNA species that are methylated by TrmD, and G37 is methylated at its N1 atom of the guanine ring. It has been proposed that the dinucleotide GpG is a minimal, albeit inefficient, substrate and must therefore fit into the active site of TrmD (Redlak et al., 1997). Molecular surface representation of a TrmD dimer clearly shows that strongly conserved residues are concentrated along the active site cleft, which is defined by the methyl group of AdoMet (Figure 5A). The distance of 9.5 Å between the sulfur atom of AdoHcy and the bound phosphate ion in the ternary complex appears optimal to accommodate guanosine in a position so that the methylation target N1 of the guanine ring can be located just above the donor methyl group of AdoMet. This observation enables us to suggest that the phosphate ion trapped in the active site may mimic the phosphate on the 5′ side of G37 in the cognate tRNA. With this picture, three highly conserved residues Glu116, Arg154* and Asp169*, which are all located just around the reactive methyl group of AdoMet, may recognize the guanine ring of G37. In addition, three strictly conserved residues (Arg39, Asp50 and Tyr115) that are located adjacent to the proposed G37-binding cleft might constitute the binding site for the G36 residue (Figure 5A). Asp50 may interact with one side of the guanine ring (i.e. N2 and/or N3), and Arg39 may recognize the other side (i.e. N5 and/or O6) in a mode similar to recognition of G37 by Glu116 and Arg154*. This kind of base-specific recognition of guanine is very similar to the case of ProRS (Cusack et al., 1998), which recognizes G35 and G36. In the crystal structure of the ProRS–tRNAPro(CGG) complex, G35 is recognized by Lys353, Asp354 and Glu349. Likewise, Lys369, Arg347 and Glu340 recognize G36 (Yaremchuk et al., 2000). For the specific recognition of guanine and its discrimination from other bases, TrmD and ProRS seem to employ highly similar strategies: acidic residues (aspartate and/or glutamate) recognize the N1 and/or N2 atoms, and basic residues (arginine or lysine) interact with N5 and O6. Tyr115 of TrmD seems to interact with G36 through a hydrophobic contact that may not be specific for guanine.

Catalytic mechanism

Catalytic mechanisms proposed for various MTases share a common theme, which involves a nucleophilic attack on the methyl group of AdoMet by a negatively polarized methyl-acceptor atom of the substrate. However, activation of the nucleophiles prior to the nucleophilic attack is achieved in a variety of ways. In the case of C5-cytosine DNA MTases (M.HhaI and M.HaeIII), a covalent reaction intermediate is formed between C6 of the target adenine and the sulfur atom of a catalytic cysteine residue, which generates a resonance-stabilized carbanion at C5 (Klimasauskas et al., 1994; Reinisch et al., 1995). Catalytic mechanisms of N6-adenine DNA MTases (M.TaqI, M.RsrI and M.DpnM) and N4-cytosine DNA MTase (M.PvuII) are also well understood. All of the DNA N-MTases have a consensus catalytic sequence motif Asp/Ser/Asn–Pro–Pro–Tyr/Phe/Trp, which is referred to as motif IV, in the catalytic P-loop. In these cases, Asp/Ser/Asn acts as a catalytic base or a hydrogen bond acceptor, and a negative charge consequently is developed on the target amide nitrogen atom (Malone et al., 1995; Gong et al., 1997). N6-adenine rRNA MTases (ErmC′ and ErmAM) also have motif IV of a modified sequence, Asn–Ile–Pro–Tyr, and have been proposed to have a similar catalytic mechanism (Yu et al., 1997; Schluckebier et al., 1999).

We propose a catalytic mechanism for TrmD on the basis of structural features of the active site and by analogy to the above-mentioned N-MTases for DNA and rRNA. The methylation reaction catalyzed by TrmD most probably proceeds via base-assisted deprotonation of the N1 atom of guanine, followed by a nucleophilic attack on the reactive methyl group of AdoMet by the negatively charged N1 atom (Figure 5B). The two strictly conserved residues Glu116 and Arg154* may recognize the guanine ring of G37 and discriminate it from other bases. More specifically, Glu116 may interact with the N2 atom via hydrogen bonds and Arg154* with O6 and N7. The highly conserved Asp169* (aspartate or glutamate in all 19 TrmD sequences; Figure 3), which approaches from the lower side of the cleft (Figure 5B and C), may act as a base that accepts a proton from N1 of the target guanine, and this leads to the development of a negative charge at N1. The activated N1 atom may then make a direct nucleophilic attack on the reactive methyl group of AdoMet. It is notable that TrmD does not contain a conserved sequence ‘motif IV’ (Asp/Ser/Asn–Pro/Ile–Pro-Tyr/Phe/Trp), unlike other nucleic acid N-MTases such as N6-adenine DNA MTases, N4-cytosine DNA MTase and N6-adenine rRNA MTases.

How does TrmD recognize general structural features of tRNA?

It is an important issue to understand how tRNA-modifying enzymes such as TrmD specifically recognize their substrates. On the basis of a structural requirement for tRNA for enzymatic activity, tRNA-modifying enzymes could be classified into at least two groups (Grosjean et al., 1996). In the first group, the tertiary structure of tRNA does not appear to be so crucial for substrate recognition and enzymatic activity. Members of this group can modify fragments or subdomains of tRNA. The other group of enzymes, to which TrmD belongs, requires the entire tRNA structure for maximum activity. TrmD binds to diverse tRNA species, including those lacking G residues at positions 36 and 37, but it does not methylate G37 of tRNA species without a G residue at position 36 (Holmes et al., 1992, 1995; Redlak et al., 1997). This suggests that the whole body of tRNA is likely to be involved in binding to TrmD, and its key structural features would be maintained when bound to TrmD. Furthermore, the anticodon stem–loop of tRNA is likely to make a tight fit into the active site of TrmD only in the case of cognate tRNAs with both G36 and G37.

Here we propose a model of the TrmD2–tRNA2 complex, which is largely consistent with the above observations. It shows remarkable shape complementarities as well as reasonable electrostatic complementarities between the TrmD dimer and tRNA. It also positions the tRNA anticodon loop in the vicinity of the TrmD active site. A conformational change resembling deformation of the anticodon stem–loop region in the cognate tRNAs of class IIa aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases such as ProRS (Cusack et al., 1998; Yaremchuk et al., 2000) and ThrRS (Sankaranarayanan et al., 1999) in their complexes appear to occur so that the bases at 36th and 37th positions of tRNA get closer to the active site of TrmD. Thus, we constructed a hybrid tRNA model that keeps the general tRNA structure but has such a deformation in its anticodon stem–loop, leading to a reasonable fit between the protruding G1/β3 loop of TrmD and the anticodon stem–loop of tRNA (Figure 5C and D). In this hybrid tRNA model, the acceptor stem and the CCA tail derive from the uncomplexed tRNAPhe (PDB entry 1EHZ; Shi and Moore, 2000) and the rest derives from tRNAPro in the ProRS–tRNAPro complex (PDB entry 1H4S). In the case of cognate tRNAs with G36G37 in the anticodon loop, further deformation of the anticodon stem–loop (blue arrows in Figure 5C) may occur, resulting in precise positioning of G36G37 to the proposed binding sites of TrmD (red arrows in Figure 5C). There is also a possibility that TrmD itself may undergo conformational changes upon binding to cognate tRNAs, in particular, in or around the two regions consisting of residues 44–62 and 192*–208* (Figures 3 and 5C).

In the proposed complex model, the first helix αG of the TrmD CTD plays a major role in recognizing tRNA by fitting its N-terminal part into the hinge of tRNA, whereas the second helix αH plays only a minor role. This is consistent with the fact that the residues around helix αG are highly conserved, whereas those around helix αH are not (Figure 3). Our proposed model indicates that dimerization is also likely to be essential for tRNA recognition, in addition to the formation of the active site. The two bound tRNA molecules occupy the opposite ends of the TrmD dimer, thus avoiding collision with each other. A single tRNA molecule makes an extensive contact with both subunits of the TrmD dimer, with each interface between TrmD and tRNA being contributed by both subunits. The region consisting of Asp44–Met62, including the loop G1/β3 and β-hairpin (β3–loop–β4), is contributed by the NTD of one subunit. The region consisting of Val192*–Arg208*, which includes the loop β9*/G2*, G2*, the loop G2*/αG* and the N-terminal part of helix αG*, comes from the CTD of the other subunit (Figures 3 and 5C). These two regions are highly conserved throughout the entire TrmD family (Figure 3) and show the most pronounced conformational flexibility (Figure 1B). For tRNA, three stem structures (acceptor stem, D stem and anticodon stem) and one loop region (anticodon loop) are mainly involved in the interaction with TrmD in the proposed model. It is in good accordance with tRNA mutation studies (Qian and Björk, 1997).

Although the starting point of our complex model was the observation of structural similarity between the CTD (αG/G3/αH region) of TrmD and trp repressor (DNA-binding domain), our complex model does not indicate identical modes of recognizing DNA by trp repressor and of recognizing tRNA by TrmD. In the case of trp and tet repressors, the recognition helix (equivalent to helix αH of TrmD) plays a crucial role in DNA recognition by interacting with the major groove of B-form DNA helix (Otwinowski et al., 1988; Orth et al., 2000). The suggested binding mode in our complex model is also different from those of Ffh/signal recognition particle, Rev and Tat. In the structure of signal recognition particle complex, two α-helices of the M domain of Ffh (equivalent to helices αG and G3 of TrmD) interact with the minor groove of the distorted double-helical RNA (Batey et al., 2000). If a similar mode of interaction is assumed for TrmD, it is not possible to build a reasonable model of the complex between tRNA and TrmD, because it leads to a severe overlap between tRNA and TrmD. In the case of Rev, a single α-helical peptide recognizes the major groove of A-form RNA helix (Battiste et al., 1996). In the case of Tat, the peptide that recognizes the major groove of A-form RNA helix adopts a β-turn conformation (Puglisi et al., 1995).

Conclusions

The first crystal structure of TrmD reveals several interesting features. First, the ‘SPOUT class MTase fold’, as defined by the structures of TrmD as well as three other SPOUT class MTases, is distinct from the previously defined ‘consensus MTase fold’. It is unique in possessing a deep trefoil knot structure, which provides the L-shaped cofactor-binding pocket. Secondly, AdoMet and AdoHcy bound to TrmD adopt a novel bent conformation. Thirdly, the active site is located at the subunit interface and TrmD functions as a dimer. Also, G36G37 seems to be recognized by the highly conserved residues from both subunits of TrmD. Fourthly, we could build a model of the TrmD2–tRNA2 complex that is largely consistent with the requirement for the general tRNA structural features for TrmD function. The G1/β3 loop and helix αG of TrmD are likely to play major roles in tRNA recognition.

Materials and methods

Crystallization, data collection, sequence alignment and graphics

Crystallization and X-ray data collection as well as sequence alignment and graphics are described in the Supplementary data, available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Structure solution and refinement

Seven of the eight expected selenium sites except the one at the N-terminus of the recombinant protein were located with the program SOLVE (Terwilliger and Berendzen, 1999) and the phases were improved by density modification using RESOLVE (Terwilliger, 2000). The mean figure of merit was 0.64/0.75 before/after RESOLVE in the resolution range of 20.0–2.80 Å. The resulting electron density map was of excellent quality and allowed automatic building of an initial model that accounted for ∼80% of the backbone of the polypeptide chain. At least 80% of the sequence was assigned using the program MAID (Levitt, 2000). The model was refined with the program CNS (Brünger et al., 1998), and manual model building was performed using the program O (Jones et al., 1991). Subsequently, the structure of the native TrmD in the apo form was refined with this SeMet-substituted model. In the case of binary complexes with either AdoMet or AdoHcy as well as the ternary complex with AdoHcy and phosphate, the structures were solved by the molecular replacement method involving rotation and translation searches using the apo structure as a search model. AdoMet/AdoHcy and water molecules were assigned based on Fo – Fc maps calculated with model phases. AdoMet and AdoHcy in the binary and ternary complexes are well defined by excellent electron densities. A total of 92.5–94.6% of the residues in the four refined models were in the most favored regions of the Ramachandran plot and no residues are in the disallowed regions, as analyzed by the program PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993). Table I summarizes data collection and refinement statistics.

Accession numbers

Coordinates have been deposited in the PDB under accession codes 1UAJ (apo), 1UAK (binary complex with AdoMet), 1UAL (binary complex with AdoHcy) and 1UAM (ternary complex with AdoHcy and phosphate).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor N.Sakabe and his staff for assistance during data collection at Photon Factory, beamline BL-18B (proposal number 01G147), and Dr H.S.Lee and his staff during data collection at Pohang Light Source, beamline 6B1. This work was supported by a grant from the Korea Ministry of Science and Technology (NRL-2001, grant no. M1-0104-00-0132). J.K.Y., H.J.A., H.-W.K., H.-J.Y. and B.I.L. are recipients of the BK21 fellowship.

References

- Anantharaman V, Koonin,E.V. and Aravind,L. (2002) SPOUT: a class of methyltransferases that includes spoU and trmD RNA methylase superfamilies and novel superfamilies of predicted prokaryotic RNA methylases. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 4, 71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batey R.T., Rambo,R.P., Lucast,L., Rha,B. and Doudna,J.A. (2000) Crystal structure of the ribonucleoprotein core of the signal recognition particle. Science, 287, 1232–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battiste J.L., Mao,H., Rao,N.S., Tan,R., Muhandiram,D.R., Kay,L.E., Frankel,A.D. and Williamson,J.R. (1996) α helix–RNA major groove recognition in an HIV-1 Rev peptide–RRE RNA complex. Science, 273, 1547–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björk G.R. (1998) Modified nucleosides in positions 34 and 37 of tRNAs and their predicted coding capacities. In Grosjean,H. and Benne,R. (eds), Modification and Editing of RNA. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 577–581.

- Björk G.R., Wikström,P.M. and Byström,A.S. (1989) Prevention of translational frameshifting by the modified nucleoside 1-methyl guanosine. Science, 244, 986–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björk G.R., Jacobsson,K., Nilsson,K., Johansson,M.J.O., Byström,A.S. and Persson,O.P. (2001) A primordial tRNA modification required for the evolution of life? EMBO J., 20, 231–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A.T. (1992) The free R-value: a novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures. Nature, 355, 472–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A.T. et al. (1998) Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D, 54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusack S., Yaremchuk,A., Krikliviy,I. and Tukalo,M. (1998) tRNAPro anticodon recognition by Thermus thermophilus prolyl-tRNA synthetase. Structure, 6, 101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W., O’Gara,M., Blumenthal,R.M. and Cheng,X. (1997) Structure of PvuII DNA-(cytosine N4) methyltransferase, an example of domain permutation and protein fold assignment. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 2702–2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean H., Edqvist,J., Stråby,K.B. and Giegé,R. (1996) Enzymatic formation of modified nucleosides in tRNA: dependence on tRNA architecture. J. Mol. Biol., 255, 67–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L. and Sander,C. (1993) Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J. Mol. Biol., 233, 123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes W.M., Andraos-Selim,C., Roberts,I. and Wahab,S.Z. (1992) Structural requirements for tRNA methylation. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 13440–13445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes W.M., Andraos-Selim,C. and Redlak,M. (1995) tRNA-m1G methyltransferase interactions: touching bases with structure. Biochimie, 77, 62–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T.A., Zou,J.-Y., Cowan,S.W. and Kjeldgaard,M. (1991) Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A, 47, 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.W., Ahn,H.J., Yoon,H.J., Kim,H.W., Baek,S.-H. and Suh,S.W. (2003) Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of tRNA(m1G37)methyltransferase from Haemophilus influenzae. Acta Crystallogr. D, 59, 183–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimasauskas S., Kumar,S., Roberts,R.J. and Cheng,X. (1994) HhaI methyltransferase flips its target base out of the DNA helix. Cell, 76, 357–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R.A., MacArthur,M.W., Moss,D.S. and Thornton,J.M. (1993) PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 26, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt D.G. (2000) A new software routine that automates the fitting of protein X-ray crystallographic electron density maps. Acta Crystallogr. D, 57, 1013–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J and Björk,G.R. (1995) 1-Methylguanosine deficiency of tRNA influences cognate codon interaction and metabolism in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol., 177, 6593–6600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J and Björk,G.R. (1999) Structural alterations of the tRNA(m1G37)methyltransferase from Salmonella typhimurium affect tRNA substrate specificity. RNA, 5, 395–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone T., Blumenthal,R.M. and Cheng,X. (1995) Structure-guided analysis reveals nine sequence motifs conserved among DNA amino-methyltransferases and suggests a catalytic mechanism for these enzymes. J. Mol. Biol., 253, 618–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J.L. and McMillan,F.M. (2002) SAM (dependent) I AM: the S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase fold. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 12, 783–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel G., Sauvé,V., Larocque,R., Li,Y., Matte,A. and Cygler,M. (2002) The structure of the RmlB 23S rRNA methyltransferase reveals a new methyltransferase fold with a unique knot. Structure, 10, 1303–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nureki O. et al. (2002) An enzyme with a deep trefoil knot for the active-site architecture. Acta Crystallogr. D, 58, 1129–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth P., Schnappinger,D., Hillen,W., Saenger,W. and Hinrichs,W. (2000) Structural basis of gene regulation by the tetracycline inducible Tet repressor–operator system. Nat. Struct. Biol., 7, 215–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z., Schevitz,R.W., Zhang,R.-G., Lawson,C.L., Joachimiak, A., Marmorstein,R.Q., Luisi,B.F. and Sigler,P.B. (1988) Crystal structure of trp repressor/operator complex at atomic resolution. Nature, 335, 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson B.C., Bylund,G.O., Berg,D.E. and Wikström,P.M. (1995) Functional analysis of the ffh–trmD region of the Escherichia coli chromosome by using reverse genetics. J. Bacteriol., 177, 5554–5560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puglisi J.D., Chen,L., Blanchard,S. and Frankel.A.D. (1995) Solution structure of a bovine immunodeficiency virus Tat–TAR peptide–RNA complex. Science, 270, 1200–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Q and Björk,G.R. (1997) Structural requirements for the formation of 1-methylguanosine in vivo in tRNAPro(GGG) of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Mol. Biol., 266, 283–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redlak M., Andraos-Selim,C., Giege,R., Florentz,C. and Holmes,W.M. (1997) Interaction of tRNA with tRNA (guanosine-1)methyltransferase: binding specificity determinants involve the dinucleotide G36pG37 and tertiary structure. Biochemistry, 36, 8699–8709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinisch K.M., Chen,L., Verdine,G.L. and Lipscomb,W.N. (1995) The crystal structure of HaeIII methyltransferase covalently complexed to DNA: an extrahelical cytosine and rearranged base pairing. Cell, 82, 143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaranarayanan R., Dock-Bregeon,A.-C., Romby,P., Caillet,J., Springer,M., Rees,B., Ehresmann,C. Ehresmann,B. and Moras,D. (1999) The crystal structure of threonyl-tRNA synthetase–tRNAThr complex enlightens its repressor activity and reveals an essential zinc ion in the active site. Cell, 97, 371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluckebier G., O’Gara,M., Saenger,W. and Cheng,X. (1995) Universal catalytic domain structure of AdoMet-dependent methyltransferase. J. Mol. Biol., 247, 16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluckebier G., Zhong,P., Stewart,K.D., Kavansaugh,T.J. and Abad-Zapatero,C. (1999) The 2.2 Å structure of the rRNA methyltransferase ErmC′ and its complexes with cofactor and cofactor analogs: implications for the reaction mechanism. J. Mol. Biol., 289, 277–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert H.L., Wilson,K.S., Raux,E., Woodcock,S.C. and Warren,M.J. (1998) The X-ray structure of a cobalamin biosynthetic enzyme, cobalt-precorrin-4 methyltransferase. Nat. Struct. Biol., 5, 585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H. and Moore,P.B. (2000) The crystal structure of yeast phenylalanine tRNA at 1.93 Å resolution: a classic structure revisited. RNA, 6, 1091–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N., Nonaka,T., Nakanishi,M., Deyashiki,Y., Hara,A. and Mitsui,Y. (1996) Crystal structure of the ternary complex of mouse lung carbonyl reductase at 1.8 Å resolution: the structural origin of coenzyme specificity in the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family. Structure, 4, 33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor W.R. (2000) A deeply knotted protein structure and how it might fold. Nature, 406, 916–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger T.C. (2000) Maximum-likelihood density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D, 56, 965–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger T.C. and Berendzen,J. (1999) Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D, 55, 849–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbonavièius J., Qian,Q., Durand,J.M.B., Hagervall,T.G. and Björk,G.R. (2001) Improvement of reading frame maintenance is a common function for several tRNA modifications. EMBO J., 20, 4863–4873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaremchuk A., Cusack,S. and Tukalo,M. (2000) Crystal structure of a eukaryote/archaeon-like prolyl-tRNA synthetase and its complex with tRNAPr°(CGG). EMBO J., 19, 4745–4758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L., Petros,A.M., Schnuchel,A., Zhong,P., Severin,J.M., Walter,K., Holzman,T.F. and Fesik,S.W. (1997) Solution structure of an rRNA methyltransferase (ErmAM) that confers macrolide–lincosamide– streptogramin antibiotic resistance. Nat. Struct. Biol., 4, 483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarembinski T.I., Kim,Y., Peterson,K., Christendat,D., Dharamsi,A., Arrowsmith,C.H., Edwards,A.M. and Joachimiak,A. (2003) Deep trefoil knot implicated in RNA binding found in an archaebacterial protein. Proteins, 50, 177–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]