Abstract

Only three Ig isotypes, IgM, IgX, and IgY, were previously known in amphibians. Here, we describe a heavy-chain isotype in Xenopus tropicalis, IgF (encoded by Cφ), with only two constant region domains. IgF is similar to amphibian IgY in sequence, but the gene contains a hinge exon, making it the earliest example, in evolution, of an Ig isotype with a separately encoded genetic hinge. We also characterized a gene for the heavy chain of IgD, located immediately 3′ of Cμ, that shares features with the Cδ gene in fish and mammals. The latter gene contains eight constant-region-encoding exons and, unlike the chimeric splicing of μCH1 onto the IgD heavy chain in teleost fish, it is expressed as a unique IgD heavy chain. The IgH locus of X. tropicalis shows a 5′ VH-DH-JH-Cμ-Cδ-Cχ-Cυ-Cφ 3′ organization, suggesting that the mammalian and amphibian Ig heavy-chain loci share a common ancestor.

Keywords: amphibians, antibody evolution

Immunoglobulins (Igs) are essential components of adaptive immunity and are produced only in gnathostomes such as mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and jawed fish (1, 2). Most mammals express five classes of Igs, IgM, IgD, IgG, IgA, and IgE, each endowed with distinct biological effector functions. Mammalian IgM and IgE heavy chains are composed of four ≈110-aa constant region domains encoded by separate exons, presumably arising from gene duplication during evolution (3). IgD and IgG contain only three domains (rodent IgD contains only two constant region domains) but also encompass a short exon-encoded hinge (genetic hinge) (4–7). IgA is also a three-domain molecule, with a functional hinge encoded by the 5′ end of the heavy-chain constant region domain (CH) 2 (CH2) exon (8, 9). The hinge regions contain one or more cysteines that are used to bridge the two heavy chains to form an H2L2 antibody structure. Hinge regions are also rich in proline, which confers conformational flexibility that allows waving, rotation of Fab arms, and wagging of the Fc fragment, thus facilitating antigen binding and triggering of effector functions (10, 11). Hinge segments have previously been observed only in mammalian Igs; however, Savan et al. (12) recently identified a heavy-chain isotype in fugu fish that contains a hinge region encoded within its CH2 exon, similar to the hinge of mammalian IgA (8, 9). This putative hinge contains five repeats of VKPT but lacks a cysteine residue to connect the two heavy chains (12).

It is generally believed that mammalian Igs arose from ancestral Igs of lower vertebrates. IgM is found in all vertebrates (13–18); however, the phylogenetic origin of the remaining mammalian Igs is less well established, although Igs referred to as IgA/IgX and IgY have been reported in birds, reptiles, and amphibians (1, 2, 19–22). Cartilaginous fish and lungfish express IgM, IgNAR, and/or IgW/IgX, containing either two or more than four constant region domains (1, 15, 23). Bony fish express three heavy-chain isotypes, IgM, IgD, and IgZ/IgT (24, 25). IgD is found in most mammals but not in birds, amphibians, or reptiles, whereas multidomain encoding Cδ genes have been described in bony fish (1, 22, 26, 27). Thus, a traditional phylogenetic pathway connecting IgD in bony fish and IgD in mammals is missing.

It has long been thought that there are only three Ig classes, IgM, IgA/IgX, and IgY, in lower vertebrates, including birds, reptiles, and amphibians (1, 2, 14, 19–22). The heavy chains that have been characterized to date in these species contain four constant region domains (except for a truncated IgY containing two domains in some species) but no hinge (28). cDNAs encoding the heavy chains of IgM, IgX, and IgY have all been cloned previously in Xenopus laevis (14, 19, 20). IgX has been considered to be an analogue of mammalian IgA because a large number of IgX-positive B cells are located in the gut epithelium (29). IgX is structurally distinct from mammalian IgA but is similar to chicken IgA (19, 30). IgY, also consisting of four constant region domains, is found in a variety of birds, amphibians, and reptiles (31) and is regarded as a functional homologue of IgG and the progenitor of both mammalian IgG and IgE (31).

In the last two decades, molecular approaches have facilitated the investigation of the genomes in a variety of species. IgZ was recently discovered in zebrafish (24). The recent assembly of the Xenopus tropicalis genome sequence allowed us to perform a search for additional Ig heavy-chain constant region genes in an amphibian.

Results

Identification of the Genomic Sequence Encoding IgM (μ), IgX (χ), and IgY (υ) in X. tropicalis.

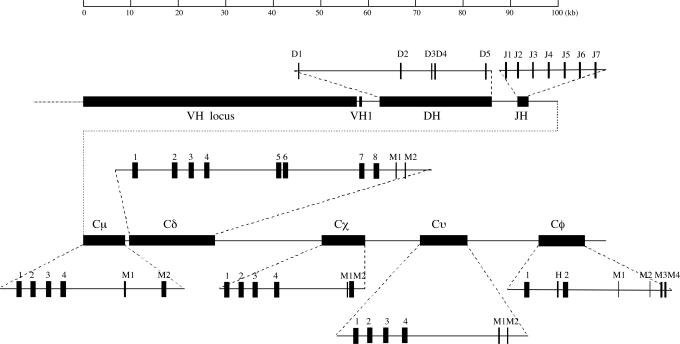

The X. tropicalis genome is available in the X. tropicalis Genome Sequencing Project database at the Sanger Institute (www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/X_tropicalis/). By using the published Ig sequences in X. laevis as templates, the Cμ, Cχ, and Cυ genes in X. tropicalis were all identified in an assembled scaffold (Scaffold_928) where the Cχ is located ≈40 kb downstream of the Cμ. The constant regions were all deduced on the basis of both genomic sequences and EST clones. The organization of the genes is presented in Fig. 1. The amino acid sequences of all three classes displayed a high degree of divergence between X. tropicalis and X. laevis (Figs. 6–8, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), with sequence similarities of only 74.3%, 82.1%, and 75.0% for IgM, IgX, and IgY, respectively. There is a cysteine located at the carboxyl-terminal end of the IgX of X. tropicalis that may be used for binding to the J chain. This cysteine is absent in the IgX sequence of X. laevis (Fig. 7) (19).

Fig. 1.

Assembly of the X. tropicalis IgH gene locus. VH, heavy-chain variable genes; DH, heavy-chain diversity gene segments; JH, heavy-chain joining gene segments; Cμ, IgM encoding gene; Cδ, IgD encoding gene. The filled boxes indicate exons encoding structurally conserved IgC domains: Cχ, IgX encoding gene; Cυ, IgY encoding gene; Cφ, IgF encoding gene; M, membrane exon. The domains encoding exons of each constant region gene are indicated with Arabic numbers. The position of the χCH1 exon is uncertain because it is missing in Scaffold_928 due to a small sequence gap.

Identification of an IgD-Encoding Gene (Cδ) in X. tropicalis.

The long stretch (≈40 kb) of intervening DNA between the Cμ and Cχ genes encouraged us to look for an IgD-encoding gene. A BLAST search that permitted some local mismatches was performed against the genome database, using the sequence of the transmembrane region of IgM from X. tropicalis as a template. This procedure identified a putative transmembrane-encoding region that could not be ascribed to IgM, IgX, or IgY heavy-chain encoding genes in Scaffold_928. This DNA sequence is located between the Cμ and Cχ genes and encodes a short peptide similar to IgM and IgD transmembrane regions in other species (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) (32), suggesting the presence of an additional heavy-chain constant region gene. To test this possibility, we used a nested RT-PCR to amplify cDNA transcripts from spleen RNA, using primers that cover the most-expressed JH genes (JH3, see below) and the putative exon for the transmembrane region. Sequence analysis of the amplified product revealed a heavy-chain transcript with eight CH exons, plus exons for M1 and M2 segments (Figs. 1 and 2, and Fig. 10, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Fig. 2.

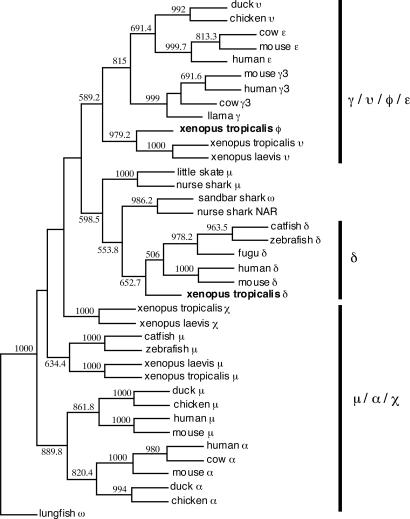

Structure of IgD heavy chains in different vertebrates. Catfish IgD (GenBank accession no. U67437); human IgD (GenBank accession no. AAB21246); H, hinge region.

The constant region heavy-chain gene we describe is located immediately downstream of the Cμ gene (1.3 kb downstream of the μM2 exon). The 1.3-kb DNA seems too short to accommodate DNA elements such as an I region promoter, an I exon, and a switch region, all of which are required for class switch DNA recombination. Nor was any repetitive sequence, suggestive of a switch region, observed by dot-plot analysis of the 1.3-kb sequence (see below). Thus, the identified gene is most likely expressed through cotranscription with the Cμ gene, supporting the notion that it may be the homologue of fish and mammalian Cδ. This hypothesis was further supported by a phylogenetic analysis in which the gene clustered with fish and mammalian Cδ genes (Fig. 3). Moreover, the deduced transmembrane region of this heavy-chain class, which is encoded by two separate exons, shows a high similarity to IgD in cows and sheep (Fig. 9). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that the identified gene is a Cδ gene in X. tropicalis. Surprisingly, a BLAST analysis showed that the X. tropicalis IgD had the highest overall similarity to the lungfish IgW, indicating that IgD and IgW may have a common origin (33).

Fig. 3.

An unrooted phylogenetic tree of Igs in vertebrates. The tree was constructed by using protein sequences of the first and last CH domains (fish δCH6 and Xenopus δCH7 were used as the last domain) of all heavy-chain classes. Except for the Ig sequences obtained in this study, all other sequences were taken from the GenBank database, with the following accession numbers: Cδ gene: catfish (AF363450), fugu (AB159481), human (BC021276), mouse (J00449), and zebrafish (BX510335); Cμ gene: catfish (M27230), chicken (X01613), duck (AJ314750), human (X14940), mouse (V00818), nurse shark (M92851), little skate (M29679), X. laevis (BC084123), and zebrafish (AY643751); Cα gene: chicken (S40610), cow (AF109617), duck (U27222), human (P01877), and mouse (BC010324); Cε gene: cow (BTU63640), human (AK130825), and mouse (X01857); Cγ gene: cow (S82407), human (BX640623), llama (AF305955), and mouse (AY498569); Cυ gene: chicken (X07174), duck (AJ314754), and X. laevis (X15114); and Cχ gene: X. laevis (BC072981), nurse shark NAR (U18701), sandbar shark IgW (U40560), and lungfish IgW (AF437727).

Unlike fish IgD, in which the μCH1 is spliced onto the IgD sequences to form a chimeric heavy chain (27), the cloned X. tropicalis IgD sequences showed that the JH-encoding gene segments were spliced directly onto the δCH1 exon, generating a unique IgD heavy chain (Fig. 2). Correspondingly, there are two cysteines in the Xenopus δCH1 (Fig. 10) that could be used to link heavy chains and light chains; these cysteines are absent in catfish δCH1 (27).

Structural analysis of the X. tropicalis Cδ gene showed that it spanned ≈18 kb of genomic DNA and consisted of eight CH exons, where exons 5 and 6 are homologous to exons 7 and 8 (82% and 76% homology at the DNA level, respectively), suggesting intragene exon duplication similar to that observed in fish IgD (34). We furthermore performed domain-to-domain sequence comparisons to determine the sequence homology of the X. tropicalis IgD with its equivalents in catfish and humans. This analysis revealed homology of the Xenopus δCH1 with the δCH1 domains of catfish and humans and homology of the Xenopus δCH7 and the catfish δCH6 with the human δCH3 (27) (Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Identification of IgF, a Hinge-Containing Ig Heavy-Chain Isotype in X. tropicalis.

The large EST database of X. tropicalis available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank database (1,037,711 EST clones as of April 30, 2006) enabled analysis of EST clones harboring rearranged V(D)J sequences. Most of these clones contained IgM, IgX, or IgY heavy chains. However, two EST clones (Gen Bank accession nos. DR836854 and CF378719) contained a rearranged V(D)J segment and a CH-like sequence distinct from that of the IgM, IgD, IgX, and IgY heavy chains. A further search in the GenBank database revealed a completely sequenced, but not annotated, cDNA clone (GenBank accession no. BC087793) derived from the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute X. tropicalis EST project. This cDNA clone would code for an Ig heavy-chain sequence containing a 137-aa variable region (including a signal peptide) and a short constant region (of 230 aa) (Fig. 11, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). On the basis of an NCBI conserved domain search, the latter region is divided into two Ig constant region domains and a short interconnecting polypeptide. Marked differences between the deduced amino acid sequences and those of X. tropicalis IgM, IgD, IgX, and IgY suggest that the cDNA clone represents a secreted form of a heavy-chain isotype in X. tropicalis. We termed this isotype “IgF” (encoded by the Cφ gene).

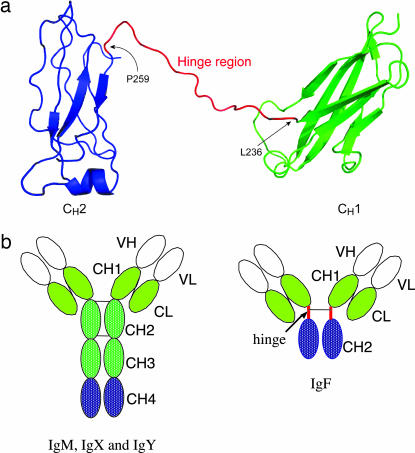

The genomic sequence encoding the heavy-chain constant region of IgF was obtained by searching the X. tropicalis Genome Sequencing Project database. The Cφ gene was found to be present in another assembled scaffold (Scaffold_972). Alignment of the IgF cDNA sequence (Fig. 11) with the genomic sequence showed that the Cφ gene consists of three exons, two of which (CH1 and CH2) encode constant region domains. The short polypeptide between these domains is encoded by a separate exon, suggesting the presence of a putative hinge region (Figs. 1 and 11). We subsequently performed a protein structure prediction based on comparative modeling (i.e., protein fold recognition) by using 1D and 3D sequence profiles and employing the web-based software 3D-PSSM (35). A loop linking the CH1 and CH2 domains was identified that involved residues 236–259 (Fig. 4), in agreement with the amino acid sequence alignment (Fig. 11). This loop may potentially serve as a hinge between the CH1 and CH2 domains (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Structure of Igs in X. tropicalis. (a) A ribbon representation of the predicted structural model of the X. tropicalis IgF heavy chain. The CH1 and CH2 domains are colored green and blue, respectively. The putative hinge region between the two domains is colored red. Note that the hinge between CH1 and CH2 contains a gap (Ser-248 to Gly-252), which is due to the absence of corresponding residues in the template structure. The figure was prepared with PyMOL software. (b) Domain structure of IgF as compared with IgM, IgX, and IgY. There is only one cysteine in the C terminus of the CH2 domain of IgM for potential inter-heavy-chain disulfide bonding. CH, heavy-chain constant region domain; CL, light-chain constant region domain; VH, heavy-chain variable region; VL, light-chain variable region.

The putative hinge region of the X. tropicalis IgF contains a conserved cysteine that may covalently link the two IgF heavy chains. The presence of three prolines is also reminiscent of the amino acid sequences in the hinge regions of mammalian Igs.

The transmembrane and cytoplasmic regions of the membrane-bound form of IgF were cloned by using 3′ RACE PCR (Fig. 12, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). As seen in Fig. 1, the C terminal of the IgF membrane-bound form is encoded by four exons, with the last two exons (M3 and M4) encoding the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains, respectively. Two tandem repeats of a nine-amino-acid unit [DL(G/R)AWITGP] are encoded by two other short exons (M1 and M2) located between the CH2 and transmembrane domains. PCR amplification of two different transcripts indicated that IgF may be expressed in both secreted and membrane-bound forms.

Assembly of the Ig Heavy-Chain Gene Locus in X. tropicalis.

In mammals and birds, the IgH genes are organized as a large cluster containing VH-DH-JH-CH genes and spanning hundreds to thousands of kilobases. To assemble the X. tropicalis IgH gene locus, we used sequence data generated by the X. tropicalis Genome Sequencing Project. The VH, DH, JH, and four constant region genes, including Cμ, Cδ, Cχ, and Cυ, are all contained within the 298-kb Scaffold_928, whereas the Cφ gene is located on a second scaffold (Scaffold_972). The presence of ≈5 kb of overlapping sequences at their ends suggested that these two scaffolds might be linked. To confirm this notion, we performed a long-distance PCR amplification (Fig. 13, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). End-sequencing of the amplified 15-kb PCR product clearly showed that Scaffold_972 is positioned downstream of Scaffold_928. The Cφ gene is located ≈15 kb downstream of the Cυ gene; the deduced organization of the X. tropicalis Ig heavy-chain gene locus is shown in Fig. 1. The entire IgH locus was thoroughly annotated except for the VH gene locus. As shown in Fig. 1, the DH locus spans ≈24 kb of DNA and is located 3 kb downstream of the most 3′ VH gene. It contains only five DH gene segments, which is fewer than in most other species (36), but there are sequence gaps between DH1 and DH2 and between DH4 and DH5, and some DH genes may thus be missing. This observation may explain why none of the five identified DH genes is found in the V(D)J junction of the IgF presented in Fig. 3. Each DH segment is flanked on both sides by classical nonamer and heptamer recombination signal sequences, separated by a conserved 12-bp spacer (Fig. 14, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Seven JH gene segments were identified ≈5 kb downstream of the DH locus (Figs. 1 and 14). According to a BLAST search against the X. tropicalis EST database, the JH3 gene segment is the most frequently used segment in the expressed V(D)J sequences (19/28), followed by JH1 (4/28) and JH2 (3/28). We did not find sequences characteristic of the conserved 5′ intronic enhancer that is located between the JH and Cμ genes in mammalian Ig heavy-chain constant region gene loci (37).

To identify putative switch region sequences for the constant region genes in X. tropicalis, we performed sequence comparisons with dot-plot analysis. An ≈2.7-kb region containing short repetitive sequences (63% A+T content) could be identified ≈1.4 kb upstream of the μCH1 exon, suggesting the presence of a switch μ region (Sμ) (Fig. 15a, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The Sμ region is abundant in AGCT motifs but is shorter than the previously reported Sμ (≈5 kb) in X. laevis (38). Such a long repetitive block could not be found in the DNA regions upstream of Cυ or Cφ, although these regions all show a high AT content (>60%) and contain some repetitive sequences (Fig. 15d and e). An ≈750-bp DNA region containing a repetitive sequence was, however, observed upstream of the Cχ gene (Fig. 15c). The 1.3-kb intron sequence between the Cμ and Cδ genes is devoid of any possible candidate sequence for a switch region according to the dot-plot analysis (Fig. 15b).

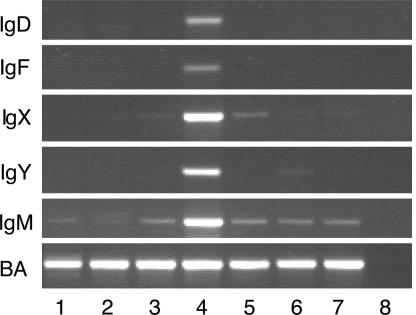

Expression of IgF and IgD in X. tropicalis.

With RT-PCR, we could show that both IgF and IgD are expressed mainly in the spleen (Fig. 5), whereas IgM is expressed in nearly all tissues investigated. In accordance with previous observations (29, 39), IgX was detected in the spleen, intestine, and stomach. Expression of IgF and IgD in the spleen is weaker than expression of IgM, IgX, and IgY, which probably explains the rareness of IgF and IgD EST clones in the NCBI EST database. Hsu et al. (39) have previously shown that a short Ig with an estimated size similar to IgF (slightly longer than two domain light chains) could be precipitated by rabbit anti-Xenopus Igs in X. laevis, suggesting that IgF is a functional heavy-chain isotype in Xenopus. However, their results did not show any secreted Ig corresponding to IgD in size (nine domains), indicating that, as in mammals, IgD is expressed at a very low level in serum.

Fig. 5.

Expression of X. tropicalis IgD, IgF, IgX, IgY, and IgM in different organs as detected by RT-PCR. BA, β actin; 1, kidney; 2, thymus; 3, intestine; 4, spleen; 5, stomach; 6, liver; 7, caecum; 8, negative control.

Discussion

In the present study, we have identified two Ig isotypes, IgD and IgF, in X. tropicalis. To our knowledge, these Ig classes have not previously been described in amphibians. We have also shown that the X. tropicalis IgH locus is organized in VH-DH-JH-Cμ-Cδ-Cχ-Cυ-Cφ order, thus conforming to the typical translocon configuration observed in mammals and fish (24, 37).

Unexpectedly, the IgF heavy chain we identified contains a hinge region and only two constant region domains. Antibodies containing two constant region domains have previously been found in cartilaginous fish, lungfish, and ducks (13, 23, 28, 40); however, these antibodies are generated through the use of different transcription termination sites or through alternative RNA splicing of the full-length transcript (13, 28). Identification of a two-domain Ig heavy-chain isotype has also recently been reported in fugu (12). This isotype corresponds to zebrafish IgZ in terms of position relative to IgM but is structurally different because it contains a hinge-like sequence within the CH2 domain-encoding exon (12). The discovery of IgF in X. tropicalis, together with the recent findings in fugu described above (12), suggest that the Ig hinge region had already evolved in lower vertebrates.

The flexibility of the Fab arms of antibodies is important for their functional properties. Thus, most mammalian Igs contain a sequence for a hinge, encoded either by a dedicated exon (genetic hinge) or by part of a regular exon (functional hinge). Because they have previously been found only in mammals, hinge regions are believed to have emerged independently in Cδ, Cγ, and Cα after the divergence of mammals from other tetrapods (3, 33, 41). It has previously been proposed that the hinge may either be evolutionarily condensed from an ancestral constant region domain encoding exon (3, 31, 42) or that it evolved by duplication, leading to incorporation of an acceptor RNA splice site (rich in the pyrimidines that are required to encode prolines) into the 5′ portion of the CH exon (5, 8, 9). If the original splice site of the CH exon is still used for RNA splicing, the newly incorporated splice site would thus encode a proline-rich hinge segment attached to the N terminus of the CH domain (5, 8, 9). According to the latter model, further mutations creating a donor splice site may lead to detachment of the hinge exon and formation of a domain relic (the CH exon was inactivated into an intronic sequence) (5, 8, 9). Sequence analysis of the IgF hinge seems to support the latter hypothesis. First, the 3′ end of the IgF hinge exon (CCTCCATAATGCCAG) is very similar to a 3′ intronic splice site. Second, the intron (347 bp) between the hinge and CH2 exons shows homology with the CH2 exon (Fig. 16, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) and may thus be a domain relic as a consequence of evolution to a detached hinge exon (8). Interestingly, there appears to be another 3′ intronic splice site in the CH2 exon, immediately upstream of the homologous sequence of the domain relic (Fig. 16), which provides additional support for the notion that a shifting of splice sites has been involved in the formation of the hinge exon.

When separate IgF CH domains were used for BLAST searches, the IgF CH2 showed the highest homology to the CH3 domain of llama and camel IgG in non-Xenopus Igs, whereas the IgF CH1 was similar to the CH1 of dog and panda IgG, strongly suggesting that IgF is related to mammalian IgG. This finding also explains why IgF clusters with IgY and mammalian IgG in a phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 3). In addition to the sequence similarity, hinge regions of both IgG and IgF are encoded by a separate exon, whereas the mammalian IgA hinge is usually encoded within the CH2 exon.

The high degree of sequence homology between the υCH1 and φCH1 exons (Fig. 17, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) indicates that the Cφ gene may originally have been duplicated from the Cυ gene. This notion is also supported by a sequence analysis that suggests that both the Cυ and Cφ genes are evolutionarily close to the Cγ and Cε genes of mammals (Fig. 3). IgY is regarded as a precursor of both IgE and IgG (31). Structural similarity (both display a four-domain structure), sequence homology, and shared biological properties of the IgY and IgE heavy chains support the view that IgY or an IgY-like Ig was the immediate predecessor of IgE (31, 43). The IgY-to-IgG transition must, however, have been accompanied by structural changes that led to the creation of a hinge region in modern IgG molecules. Thus, IgF may share a common hinge-containing ancestor with the mammalian IgG. However, hinge formation in IgF in Xenopus and hinge formation in IgG in mammals appear to be independent events, inasmuch as the domain relic is located immediately downstream of the IgF hinge exon but upstream of the hinge exon in the mouse Cγ2b encoding gene (5, 8). Accepting that the IgG hinge developed after the emergence of mammalian species, the IgF hinge may also have been formed after the divergence of amphibians. Thus, the hinge regions of IgF and IgG may be a consequence of convergent evolution.

Because the CH2 of IgF shows a high homology with llama and camel IgG, we further compared the composition of the hinges in these Igs and the recently reported hinge in fugu (12, 44). The comparison showed that fugu and camel hinges are both characterized by distinct repeats (VKPT in fugu and PKPQP in camel) that are slightly similar to the C terminus of the IgF hinge (NTKP) (12, 44). The low sequence similarity of hinges in different species is not surprising because the hinge regions appear to have evolved rapidly (45). The fugu hinge lacks the cysteine that is used to bridge the two heavy chains (12, 44). It is thus likely that additional steps (either mutation or generation of another cysteine-containing segment) were involved in the formation of some hinges that are based on a preexisting segment (or sometimes duplicated segments).

IgD has previously been found only in mammals and fish but not in birds and amphibians (6, 27). The discovery of IgD in X. tropicalis partially fills this evolutionary gap. The genomic organization of the Cδ gene appears to be similar to its equivalent in fish, inasmuch as the IgD-encoding genes are all encoded by more than four CH exons (24, 27). However, splicing of the μCH1 exon onto the IgD sequences, a mechanism that is used to express IgD in fish (27, 46), is not observed in X. tropicalis. Rather, the expression of IgD is similar to that in mammals, where rearranged V(D)J sequences are joined directly to the Cδ sequence. The fact that the transmembrane portion of the X. tropicalis IgD displays a higher degree of homology with the IgD of mammals than of fish (Fig. 9) suggests that X. tropicalis IgD is an evolutionary intermediate between the IgD of fish and mammals and that the Cδ gene has undergone a condensing process in mammals.

The availability of the genome sequence of a species made the present study possible and has confirmed and extended information already known from X. laevis. The sequence also has provided evidence for IgD in a tetrapod considered more primitive than mammals and has also provided the evolutionarily earliest evidence of an Ig isotype with a separately encoded hinge exon. Presence of five Ig heavy-chain isotypes in X. tropicalis suggests that its IgH locus shares a common ancestor with mammals.

Materials and Methods

RNA and DNA Isolations.

Frogs (X. tropicalis) were purchased from NASCO (Fort Atkinson, WI). RNA isolations were conducted by using either the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) or Trizol (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH), in accordance with standard manufacturer’s instructions. The dissected tissues were homogenized by using iron beads and used directly in RNA isolations. DNA isolations were performed with either DNAzol or phenol extraction. First-strand cDNA synthesis was conducted with either random or NotI-d(T)18 primers.

RT-PCR Detection of Transcriptions of the X. tropicalis Ig Heavy-Chain Genes in Different Organs.

The synthesized cDNA samples with RNA isolated from different organs were used in RT-PCR to detect expression of IgF, IgY, IgX, IgM, and IgD; the Xenopus β actin gene was used as a control. (The primers are listed in Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.)

Rapid Amplification of the IgF cDNA 3′ End (3′ RACE).

Approximatley 400 ng of spleen total RNA was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA with a First-Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). The primers used in the 3′ RACE are listed in Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. The resulting PCR products were purified by using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and subsequently cloned into a T vector and sequenced (MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany).

Amplification and Cloning of the IgD cDNA.

A nested RT-PCR was used to amplify the IgD heavy-chain cDNA, using the primers Tropicalis JHS2 (5′ GGG GAC CAG GGA CCA CGG TCA C 3′), Tropicalis JHS3 (5′ ACC ATG GTC ACC GTC ACT TCA G 3′), Tropicalis IgDFullas1 (5′ GTG CAG GTA AAG TAG AAT AGT T 3′), and Tropicalis IgDFullas2 (5′ ATG GTC AGT TTC CTT CTT GGT A 3′). The resulting PCR products were cloned into a T vector and sequenced.

Long-Distance PCR Amplification of the DNA Fragment Between the Cυ and Cφ Genes.

To determine the position of Scaffold_972 relative to Scaffold_928 and the distance between the Cυ and Cφ genes, we performed a long-distance PCR amplification by using one primer, IgYTMs (5′ GAC CAC GGC TAT CAC ATT TAT CTC 3′), derived from the IgY transmembrane region, and IgFCH1as (5′ GAA ATC CAG AAG CAA AGC ATC CAA 3′), derived from the IgF CH1 exon by using the Expand Long Template PCR system (Roche Diagnostics). The amplified 15-kb DNA fragment was recovered and directly sequenced from both ends by using the original PCR primers to confirm the sequence identity.

Annotation of the X. tropicalis IgH Gene Locus.

Whereas the NCBI EST database is used in BLAST searches for expressed sequences (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/), the genome database we used is built by the Sanger Institute (www.sanger.ac.uk/DataSearch/). DH gene segments were identified by using an online software program (FUZZNUC; (http://bioweb.pasteur.fr/seqanal/interfaces/fuzznuc.html) and searching a consensus sequence motif (CACTGTG-N12-ACAAAAACC) allowing five mismatches. Another sequence motif (GGTTTTTGT-N21–23-CACTGTG) was used to identify JH gene segments.

DNA and Protein Sequence Computations.

DNA and protein sequence editing, alignments, and comparisons were performed with the MegAlign software (DNASTAR). A phylogenetic tree was constructed by using Protpars from the PHYLIP software package. A consensus tree was taken from 1,000 bootstrapped phylogenetic trees. Multiple sequence alignments for the tree construction were performed with ClustalW. The 3D structure prediction was performed with the 3D-PSSM software (35). The resulting structure, based on the template structure of mouse IgG1 (Protein Data Bank code 1IGY, 29% sequence identity), has a PSSM E-value of 0.0828, indicating a prediction certainty >90% (35). The first 20 residues on the N terminus and the last 13 residues on the C terminus of the predicted structure were omitted because of the low sequence identity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Daniel L. Weeks for providing samples from X. tropicalis, Prof. Rudolf Ladenstein for structure modeling, and Dr. Sicheng Wen for technical help in preparing the figures. This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council and the National Natural Science Fund of China.

Abbreviation

- CH

heavy-chain constant region domain.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Flajnik M. F. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:688–698. doi: 10.1038/nri889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stavnezer J., Amemiya C. T. Semin. Immunol. 2004;16:257–275. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin L. C., Putnam F. W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:504–508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.1.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tucker P. W., Liu C. P., Mushinski J. F., Blattner F. R. Science. 1980;209:1353–1360. doi: 10.1126/science.6968091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tucker P. W., Marcu K. B., Newell N., Richards J., Blattner F. R. Science. 1979;206:1303–1306. doi: 10.1126/science.117549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Y., Kacskovics I., Pan Q., Liberles D. A., Geli J., Davis S. K., Rabbani H., Hammarström L. J. Immunol. 2002;169:4408–4416. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao Y., Pan-Hammarström Q., Kacskovics I., Hammarström L. J. Immunol. 2003;171:1312–1318. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tucker P. W., Slightom J. L., Blattner F. R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:7684–7688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flanagan J. G., Lefranc M. P., Rabbitts T. H. Cell. 1984;36:681–688. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brekke O. H., Michaelsen T. E., Sandlie I. Immunol. Today. 1995;16:85–90. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roux K. H., Strelets L., Michaelsen T. E. J. Immunol. 1997;159:3372–3382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savan R., Aman A., Sato K., Yamaguchi R., Sakai M. Eur. J. Immunol. 2005;35:3320–3331. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ota T., Rast J. P., Litman G. W., Amemiya C. T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:2501–2506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0538029100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwager J., Mikoryak C. A., Steiner L. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:2245–2249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kokubu F., Hinds K., Litman R., Shamblott M. J., Litman G. W. EMBO J. 1988;7:1979–1988. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahan A., Reynaud C. A., Weill J. C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:5381–5389. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.16.5381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson M. R., Marcuz A., van Ginkel F., Miller N. W., Clem L. W., Middleton D., Warr G. W. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5227–5233. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.17.5227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turchin A., Hsu E. J. Immunol. 1996;156:3797–3805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haire R. N., Shamblott M. J., Amemiya C. T., Litman G. W. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:1776. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.4.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amemiya C. T., Haire R. N., Litman G. W. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:5388. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.13.5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Y., Rabbani H., Shimizu A., Hammarström L. Immunology. 2000;101:348–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundqvist M. L., Middleton D. L., Hazard S., Warr G. W. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:46729–46736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106221200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harding F. A., Amemiya C. T., Litman R. T., Cohen N., Litman G. W. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6369–6376. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.21.6369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danilova N., Bussmann J., Jekosch K., Steiner L. A. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:295–302. doi: 10.1038/ni1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen J. D., Landis E. D., Phillips R. B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:6919–6924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500027102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butler J. E. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2006;30:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson M., Bengten E., Miller N. W., Clem L. W., Du Pasquier L., Warr G. W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:4593–4597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magor K. E., Higgins D. A., Middleton D. L., Warr G. W. J. Immunol. 1994;153:5549–5555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mussmann R., Du Pasquier L., Hsu E. Eur. J. Immunol. 1996;26:2823–2830. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mansikka A. J. Immunol. 1992;149:855–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warr G. W., Magor K. E., Higgins D. A. Immunol. Today. 1995;16:392–398. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Y., Hammarström L. Immunology. 2003;108:288–295. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01610.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsu E., Pulham N., Rumfelt L. L., Flajnik M. F. Immunol. Rev. 2006;210:8–26. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hordvik I., Thevarajan J., Samdal I., Bastani N., Krossoy B. Scand. J. Immunol. 1999;50:202–210. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelley L. A., MacCallum R. M., Sternberg M. J. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;299:499–520. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Litman G. W., Anderson M. K., Rast J. P. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1999;17:109–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao Y., Kacskovics I., Rabbani H., Hammarström L. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:35024–35032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mussmann R., Courtet M., Schwager J., Du Pasquier L. Eur. J. Immunol. 1997;27:2610–2619. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsu E., Flajnik M. F., Du Pasquier L. J. Immunol. 1985;135:1998–2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magor K. E., Warr G. W., Middleton D., Wilson M. R., Higgins D. A. J. Immunol. 1992;149:2627–2633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hsu E. Semin. Immunol. 1994;6:383–391. doi: 10.1006/smim.1994.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakano H., Rogers J. H., Huppi K., Brack C., Traunecker A., Maki R., Wall R., Tonegawa S. Nature. 1979;277:627–633. doi: 10.1038/277627a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mussmann R., Wilson M., Marcuz A., Courtet M., Du Pasquier L. Eur. J. Immunol. 1996;26:409–414. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen V. K., Hamers R., Wyns L., Muyldermans S. Mol. Immunol. 1999;36:515–524. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00067-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sumiyama K., Saitou N., Ueda S. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002;19:1093–1099. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bengten E., Clem L. W., Miller N. W., Warr G. W., Wilson M. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2006;30:77–92. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.