Abstract

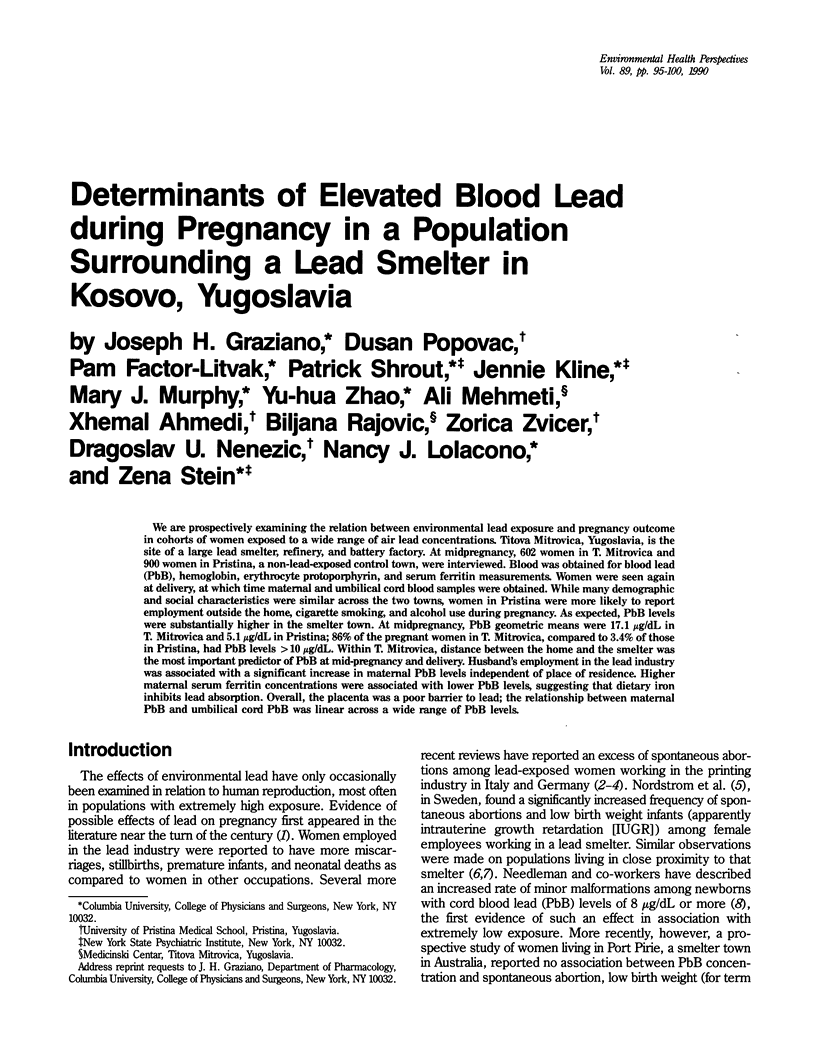

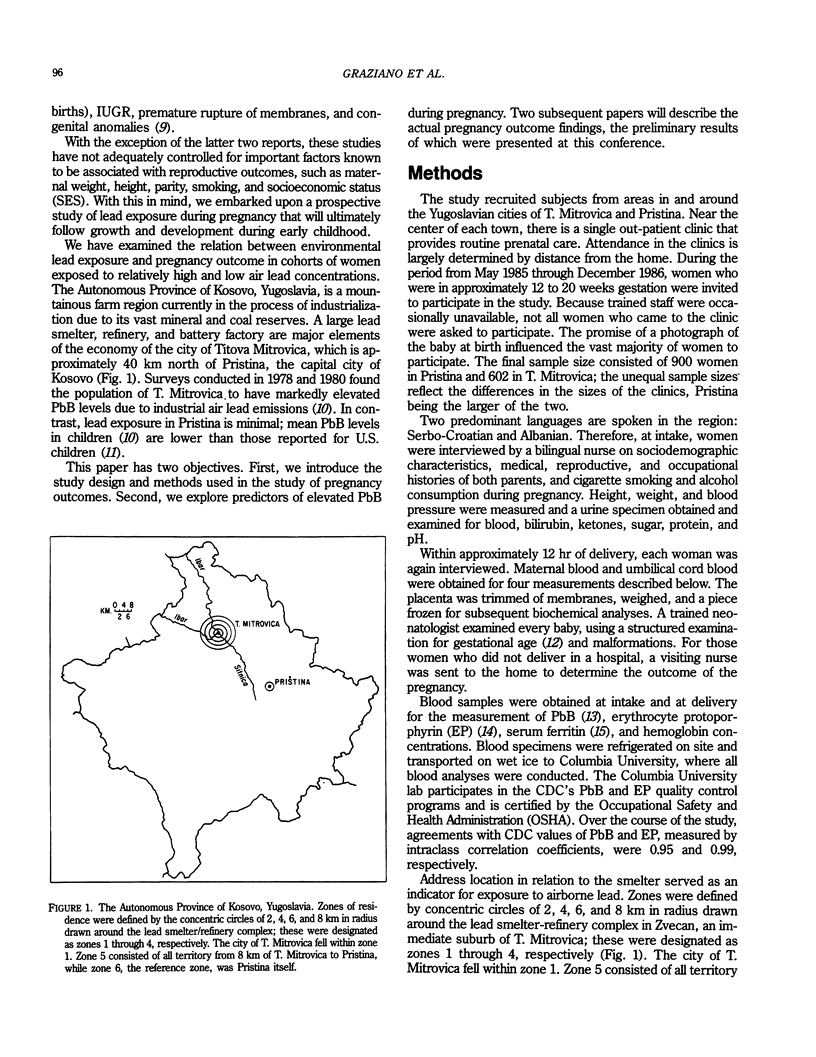

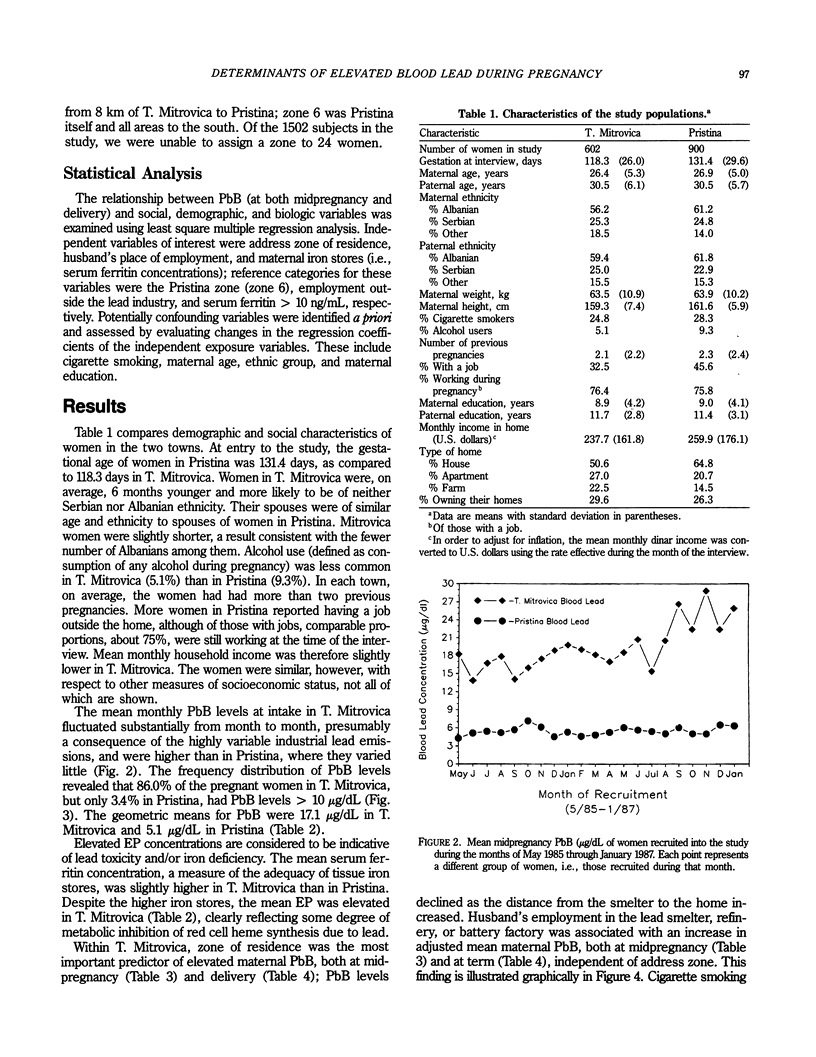

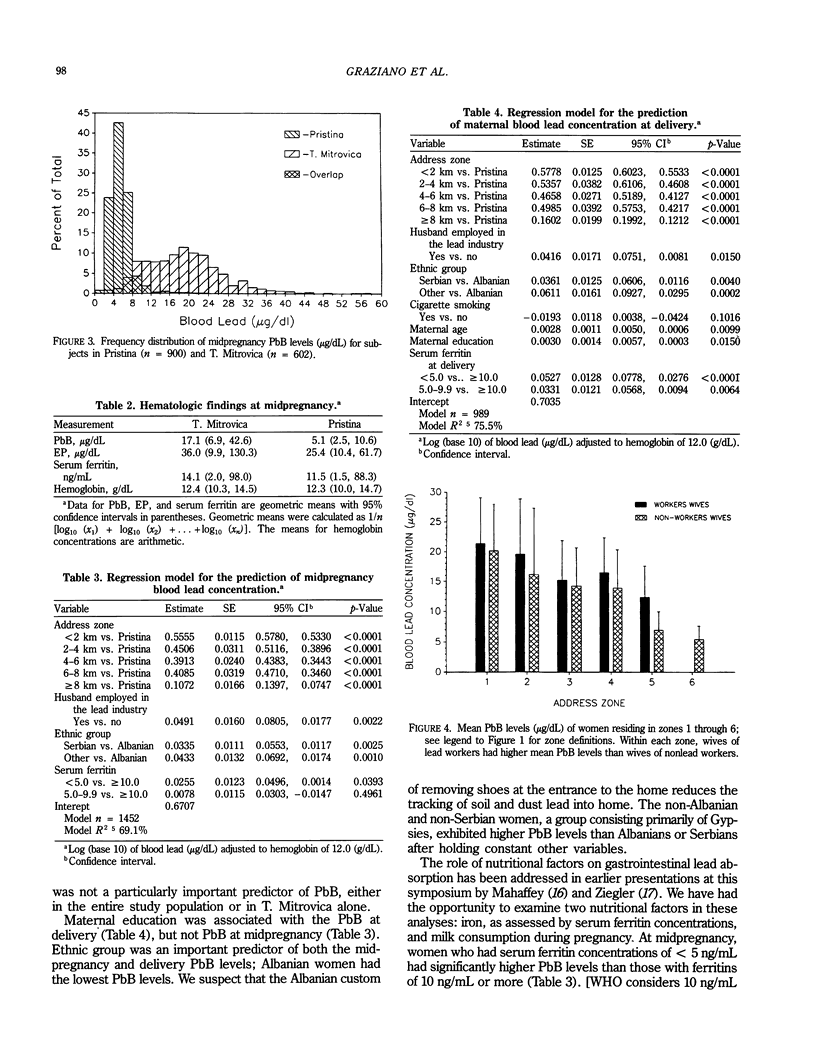

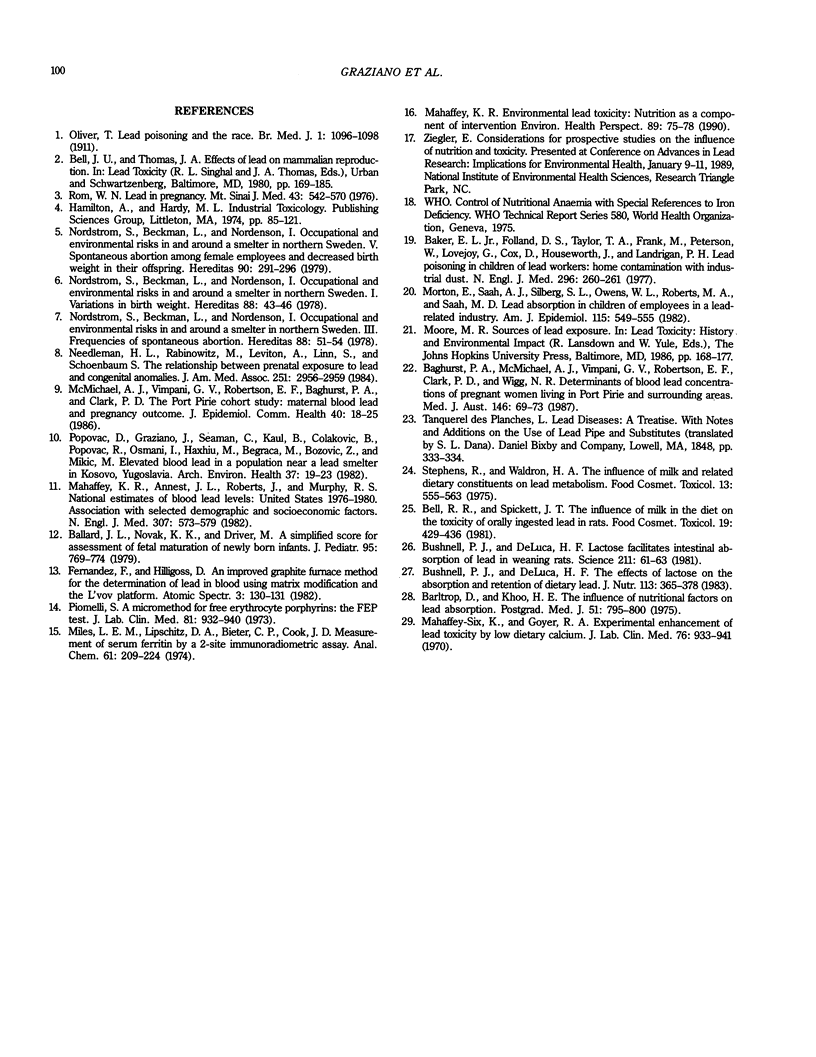

We are prospectively examining the relation between environmental lead exposure and pregnancy outcome in cohorts of women exposed to a wide range of air lead concentrations. Titova Mitrovica, Yugoslavia, is the site of a large lead smelter, refinery, and battery factory. At midpregnancy, 602 women in T. Mitrovica and 900 women in Pristina, a non-lead-exposed control town, were interviewed. Blood was obtained for blood lead (PbB), hemoglobin, erythrocyte protoporphyrin, and serum ferritin measurements. Women were seen again at delivery, at which time maternal and umbilical cord blood samples were obtained. While many demographic and social characteristics were similar across the two towns, women in Pristina were more likely to report employment outside the home, cigarette smoking, and alcohol use during pregnancy. As expected, PbB levels were substantially higher in the smelter town. At midpregnancy, PbB geometric means were 17.1 μg/dL in T. Mitrovica and 5.1 μg/dL in Pristina; 86% of the pregnant women in T. Mitrovica, compared to 3.4% of those in Pristina, had PbB levels > 10 μg/dL. Within T. Mitrovica, distance between the home and the smelter was the most important predictor of PbB at mid-pregnancy and delivery. Husband's employment in the lead industry was associated with a significant increase in maternal PbB levels independent of place of residence. Higher maternal serum ferritin concentrations were associated with lower PbB levels, suggesting that dietary iron inhibits lead absorption. Overall, the placenta was a poor barrier to lead; the relationship between maternal PbB and umbilical cord PbB was linear across a wide range of PbB levels.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baghurst P. A., McMichael A. J., Vimpani G. V., Robertson E. F., Clark P. D., Wigg N. R. Determinants of blood lead concentrations of pregnant women living in Port Pirie and surrounding areas. Med J Aust. 1987 Jan 19;146(2):69–73. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1987.tb136265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker E. L., Folland D. S., Taylor T. A., Frank M., Peterson W., Lovejoy G., Cox D., Housworth J., Landrigan P. J. Lead poisoning in children of lead workers: home contamination with industrial dust. N Engl J Med. 1977 Feb 3;296(5):260–261. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197702032960507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard J. L., Novak K. K., Driver M. A simplified score for assessment of fetal maturation of newly born infants. J Pediatr. 1979 Nov;95(5 Pt 1):769–774. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80734-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barltrop D., Khoo H. E. The influence of nutritional factors on lead absorption. Postgrad Med J. 1975 Nov;51(601):795–800. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.51.601.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell R. R., Spickett J. T. The influence of milk in the diet on the toxicity of orally ingested lead in rats. Food Cosmet Toxicol. 1981 Aug;19(4):429–436. doi: 10.1016/0015-6264(81)90446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell P. J., DeLuca H. F. Lactose facilitates the intestinal absorption of lead in weanling rats. Science. 1981 Jan 2;211(4477):61–63. doi: 10.1126/science.7444448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell P. J., DeLuca H. F. The effects of lactose on the absorption and retention of dietary lead. J Nutr. 1983 Feb;113(2):365–378. doi: 10.1093/jn/113.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahaffey K. R., Annest J. L., Roberts J., Murphy R. S. National estimates of blood lead levels: United States, 1976-1980: association with selected demographic and socioeconomic factors. N Engl J Med. 1982 Sep 2;307(10):573–579. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198209023071001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahaffey K. R. Environmental lead toxicity: nutrition as a component of intervention. Environ Health Perspect. 1990 Nov;89:75–78. doi: 10.1289/ehp.908975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMichael A. J., Vimpani G. V., Robertson E. F., Baghurst P. A., Clark P. D. The Port Pirie cohort study: maternal blood lead and pregnancy outcome. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1986 Mar;40(1):18–25. doi: 10.1136/jech.40.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles L. E., Lipschitz D. A., Bieber C. P., Cook J. D. Measurement of serum ferritin by a 2-site immunoradiometric assay. Anal Biochem. 1974 Sep;61(1):209–224. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90347-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton D. E., Saah A. J., Silberg S. L., Owens W. L., Roberts M. A., Saah M. D. Lead absorption in children of employees in a lead-related industry. Am J Epidemiol. 1982 Apr;115(4):549–555. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman H. L., Rabinowitz M., Leviton A., Linn S., Schoenbaum S. The relationship between prenatal exposure to lead and congenital anomalies. JAMA. 1984 Jun 8;251(22):2956–2959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordström S., Beckman L., Nordenson I. Occupational and environmental risks in and around a smelter in northern Sweden. I. Variations in birth weight. Hereditas. 1978;88(1):43–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.1978.tb01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordström S., Beckman L., Nordenson I. Occupational and environmental risks in and around a smelter in northern Sweden. III. Frequencies of spontaneous abortion. Hereditas. 1978;88(1):51–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.1978.tb01602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordström S., Beckman L., Nordenson I. Occupational and environmental risks in and around a smelter in northern Sweden. V. Spontaneous abortion among female employees and decreased birth weight in their offspring. Hereditas. 1979;90(2):291–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piomelli S. A micromethod for free erythrocyte porphyrins: the FEP test. J Lab Clin Med. 1973 Jun;81(6):932–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovac D., Graziano J., Seaman C., Colakovic B., Popovac R., Osmani I., Haxhiu M., Begraca M., Bozovic Z., Mikic M. Elevated blood lead in a population near a lead smelter in Kosovo, Yugoslavia. Arch Environ Health. 1982 Jan-Feb;37(1):19–23. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1982.10667527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rom W. N. Effects of lead on the female and reproduction: a review. Mt Sinai J Med. 1976 Sep-Oct;43(5):542–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Six K. M., Goyer R. A. Experimental enhancement of lead toxicity by low dietary calcium. J Lab Clin Med. 1970 Dec;76(6):933–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens R., Waldron H. A. The influence of milk and related dietary constituents on lead metabolism. Food Cosmet Toxicol. 1975 Oct;13(5):555–563. doi: 10.1016/0015-6264(75)90022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]