Bit by bit the barriers to achieving differentiation of desired somatic cells from human embryonic stem cells (hESC) are falling away. In a recent issue of PNAS, Galić et al. (1) reported that hESC can be made to differentiate to mature T cells. Prior reports have shown the capacity of mouse ESC (mESC) to accomplish this process, and getting hESC to form other blood elements has been well described. To some, it would seem then that yet another report of hESC becoming a cell type of interest is no big deal. The cells are after all pluripotent and should make any and all mature cell types. The challenge, of course, is to actually drive the cells down a particular lineage pathway and ultimately to be able to do this on command. Getting there requires some serious spade work: first, showing that hESC lines can become the cell of interest; second, developing a system to accomplish it with high frequency and purity; and third, using that system to define the specific molecular cues that are necessary and sufficient. The field is still in need of the first step, and those who work through it deserve much credit.

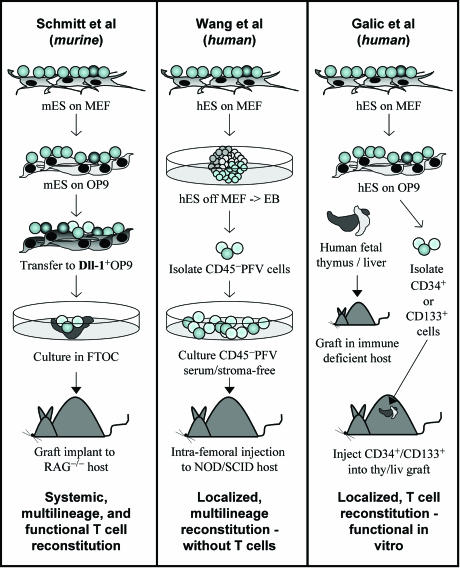

The approaches used by researchers to generate blood cells, specifically hematopoietic stem cells (HSC), from ES cells fall into two basic categories (Fig. 1). ES cells, when withdrawn from their pluripotent-maintaining feeder layers, form macroscopic spherical structures with differentiated cells from the three germ layers. Depending on the conditions under which these embryoid bodies (EBs) are cultured, a variety of lineages can be detected upon EB dispersal. Many groups have identified hematopoietic progenitor production in EBs that display in vitro and limited in vivo capacity to generate multilineage blood cells (2, 3). Alternatively, ES cells may be removed from their mouse embryo fibroblast (MEF) feeder layers in favor of stromal lines that support hematopoietic development from somatic-derived populations (4–6). Using combinations of these methods, several groups have succeeded in generating mESC-derived, transplantable hematopoiesis in recipient hosts.

Fig. 1.

Generation of blood cells from ES cells. (Left) mESC were grown on OP9 feeders followed by Dll-1+ OP9 cells and subsequent transfer to fetal thymic organ culture (FTOC). Transplant of the seeded FTOC into RAG−/− hosts generated T cells responsive to an in vivo viral challenge (12). (Center) hESC were differentiated into EBs for 10 days. CD45−, PECAM-1+, Flk-1+, and VE-cadherin+ (PFV) cells were isolated and grown in serum-free growth conditions and then injected intrafemorally to prevent aggregation caused by murine serum. Localized and minimal contralateral multilineage but no T lineage engraftment was obtained (8). (Right) hESC were cultured on OP9 stroma for 10–14 days, and the resulting CD34+ or CD133+ cells were isolated. SCID or RAG−/− mice harboring a human fetal thymic/liver rudiment under the renal capsule were irradiated, and ES cell-derived hematopoietic progenitors were injected within the thymus/liver (thy/liv) graft. Biopsies from the graft contained mature T cells that could be activated by anti-CD3 in vitro (1).

Mammalian hematopoiesis occurs in, and is regulated by, distinct physical environments during fetal development and in the adult. Attempts to generate HSCs from ES cells have been hampered by the finding that ES cell-derived hematopoietic cells migrate and engraft poorly when transplanted (7). Given that the functional potential of a candidate HSC population can be assayed only in a transplant setting, this characteristic of ES cell-derived HSCs has complicated an already challenging experimental pursuit.

Recent studies by Mick Bhatia’s laboratory (8) have demonstrated that hESC-derived progenitors possess at least limited hematopoietic potential when injected directly into the bone marrow of recipient, immune-compromised NOD/SCID mice. However, engraftment potential was still extremely low, and very little migration of the engrafted cells was observed. Of note, very limited T lymphocyte potential has been achieved by engrafting either mESC- or hESC-derived hematopoietic progenitors into irradiated recipients by any group thus far (3, 9, 10).

The absence of T lineage differentiation from ES-derived HSCs may stem from an inability of current culture conditions to permit T lineage precursor migration to their niche in the thymus. However, until recently, the possibility remained that ES cells do not possess robust T lineage potential. Several important papers from the Zuniga-Pflucker laboratory (11, 12) have since disproved this hypothesis, by coculturing ES cells in conditions used to generate T lineage cells from somatic hematopoietic precursors (11). They cultured mESC in contact with the OP9 stromal line, and resulting nonadherent cells were transferred to a variant of the same supporting layer modified to express the Notch ligand Delta-like1. Not only did ES-derived cells yield mature T cells that were similar in phenotype and in vitro function to somatic-derived T cells, but also these populations were transplantable into host mice (within a fetal thymic graft) and functioned to protect the recipients from a viral challenge (12).

The observation that, with the correct culture conditions, robust, functional T cells could be generated from mESC supports the notion that the same should be possible in the human system. Galić et al. (1) report a series of in vitro and in vivo steps that allowed them to get from hESC to T cells.

Galić et al. (1) also made use of coculture with the OP9 stromal line that they combined with secondary culture in human fetal thymic/liver grafts in immunodeficient mice. Remarkably, transplant of hESC-derived precursors directly into the thymic/liver graft of recipient mice resulted in discrete populations of mature T lineage cells within the graft. Furthermore, the cells could be isolated from the in vivo graft and demonstrated in vitro to have responsiveness to T cell antigen receptor-mimicking stimuli.

What are the implications of this work? First, this system could be used to assess the impact of specific genetic modifications on human T cell differentiation in vivo. Second, the Zack laboratory has long been interested in T cell deficiency syndromes, particularly those caused by HIV infection. Creating T cell precursors that might be transferred to T cell-deficient individuals would potentially be of therapeutic benefit, which would be particularly true in those who have a T cell deficiency such as some types of congenital immunodeficiency. But these individuals can be cured with standard allogeneic transplant. Why incur other potential unknowns of hESC-derived cell transplants? The answer is in the genetic manipulability of the ES cell. In mice, homologous recombination can be achieved with reasonable frequency. Whether the same can be achieved with hESC is not yet known. What is known, however, is that these cells can be generated in large numbers so that even low-frequency events may not be prohibitive the way they are with the more limited adult HSC. It is also known that these cells can be transduced with expression vectors that can be engineered to have minimal silen cing (13–15). The potential then for genetically modifying cells that could move on to become mature T cells is attractive, particularly in congenital T cell abnormalities or HIV infection. For example, consider the potential to provide large numbers of T cell precursors that have been rendered genetically resistant to HIV infection. The thymus of HIV-infected people is known to be abnormal architecturally, but functional. A population of precursor cells could theoretically be provided that would have the opportunity to mature in a host thymus. If that would allow for development of cells that have reactivity to HIV, then HIV-resistant, anti-HIV T cells could result. Although there are many unknowns on this long road to application, a population of T cells targeting HIV-infected cells could be a very attractive approach to the control of HIV. Might ES cells ultimately contribute effector cells of the immune system in such diseases? The first step suggesting such is now in place.

Embryonic stem-derived cells yield mature T cells similar in phenotype and function to somatic-derived T cells.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

See companion article on page 11742 in issue 31 of volume 103.

References

- 1.Galić Z., Kitchen S. G., Kacena A., Subramanian A., Burke B., Cortado R., Zack J. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:11742–11747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604244103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chadwick K., Wang L., Li L., Menendez P., Murdoch B., Rouleau A., Bhatia M. Blood. 2003;102:906–915. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muller A. M., Dzierzak E. A. Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 1993;118:1343–1351. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.4.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufman D. S., Hanson E. T., Lewis R. L., Auerbach R., Thomson J. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10716–10721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191362598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vodyanik M. A., Bork J. A., Thomson J. A., Slukvin I. I. Blood. 2005;105:617–626. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palacios R., Golunski E., Samaridis J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:7530–7534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyba M., Daley G. Q. Exp. Hematol. 2003;31:994–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L., Menendez P., Shojaei F., Li L., Mazurier F., Dick J. E., Cerdan C., Levac K., Bhatia M. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:1603–1614. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Potocnik A. J., Nerz G., Kohler H., Eichmann K. Immunol. Lett. 1997;57:131–137. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(97)00089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nisitani S., Tsubata T., Honjo T. Int. Immunol. 1994;6:909–916. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.6.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmitt T. M., Zuniga-Pflucker J. C. Immunol. Rev. 2006;209:95–102. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmitt T. M., de Pooter R. F., Gronski M. A., Cho S. K., Ohashi P. S., Zuniga-Pflucker J. C. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:410–417. doi: 10.1038/ni1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma Y., Ramezani A., Lewis R., Hawley R. G., Thomson J. A. Stem Cells. 2003;21:111–117. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-1-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaehres H., Lensch M. W., Daheron L., Stewart S. A., Itskovitz-Eldor J., Daley G. Q. Stem Cells. 2005;23:299–305. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menendez P., Wang L., Bhatia M. Curr. Gene Ther. 2005;5:375–385. doi: 10.2174/1566523054546198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]